INTRODUCTION

Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS) is a common cause of lateral hip pain, seen more commonly in females between the ages of 40 and 60.1,2 GTPS is the cause of hip pain in 10–20% of patients presenting with hip pain to primary care, with an incidence of 1.8 patients per 1000 per year.1–3

Traditionally thought to be due to trochanteric bursitis, surgical, histological, and imaging studies have shown that GTPS is attributable to tendinopathy of the gluteus medius and/or minimus with or without coexisting bursal pathology.1,4,5 Abnormal hip biomechanics are hypothesised to predispose to the development of these gluteal tendinopathies. Compressive forces cause impingement of the gluteal tendons and bursa onto the greater trochanter by the iliotibial band (ITB) as the hip moves into adduction. Compressive forces are increased where there is weakness of the hip abductor muscles due to lateral pelvic tilt.6

DIAGNOSIS

Patients commonly present with lateral hip pain, localised to the greater trochanter, which is worse with weightbearing activities and side lying at night.1,4,7 There may be associated radiation down the lateral thigh to the knee. Pain may progressively worsen over time and be triggered or exacerbated by sudden unaccustomed exercise, falls, prolonged weightbearing, or sporting overuse (commonly long-distance running).4

This condition carries significant morbidity; pain on side lying and subsequent reduction in physical activity levels carry negative implications for general health, employment, and wellbeing.6

It is important to accurately diagnose GTPS early, as delay and mismanagement can worsen prognosis due to progression to recalcitrant symptoms. The condition can be mistaken for common causes of hip pain including osteoarthritis of the hip, lumbar spine referred pain, and pelvic pathology.4,7 The ‘ability to put shoes and socks on’ is a useful question to differentiate GTPS from hip osteoarthritis; patients with GTPS will not have difficulty with this task.7

Single clinical tests for GTPS lack validity, but a combination of tests can be used to increase the diagnostic accuracy; during a GP consultation two that can be used are direct palpation and the single leg stance test. Direct palpation of the greater trochanter (the ‘jump sign’ as the person can be so tender they jump off the bed) carries a positive predictive value (PPV) of 83% (for positive magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] findings);5 if there is no pain on palpation the patient is unlikely to have GTPS. The single leg stance test (pain within 30 seconds of standing on one leg) has a very high sensitivity and PPV (100%) for positive MRI findings; if positive the patient is likely to have GTPS.5

Combining these two clinical tests with others can further increase diagnostic accuracy; the FABER test (flexion, abduction, and external rotation), FADER test (flexion, adduction, and external rotation), and ADD test (passive hip adduction in side lying) aim to increase tensile load on the gluteus medius and minimus tendons, causing a replication of the patient’s pain. Other associated clinical findings may include positive Ober’s test, positive step up and down test, and Trendelenburg gait positive.4

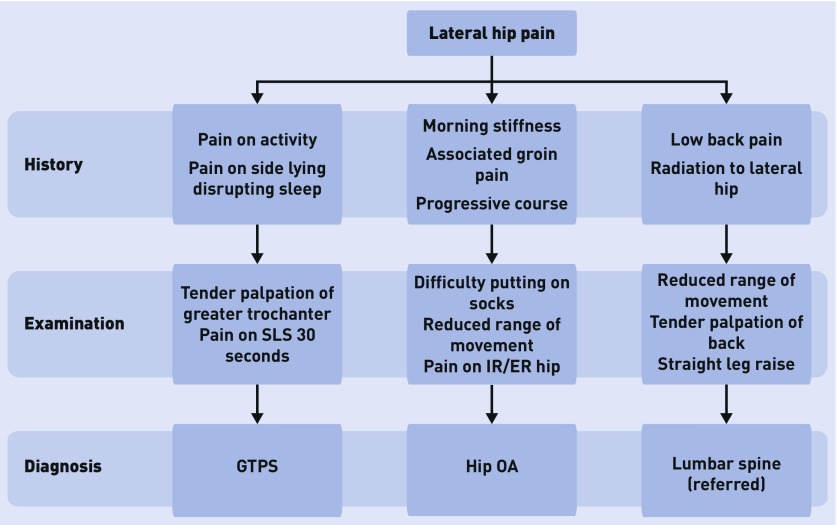

A diagnostic flow chart summarising the key clinical features for the main differentials is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A diagnostic flow chart summarising the key clinical features for the main differentials of GTPS. ER = external rotation. GTPS = greater trochanteric pain syndrome. IR = internal rotation. OA = osteoarthritis. SLS = single leg stance.

GTPS is acknowledged as being a clinical diagnosis,1 but, in recalcitrant cases or those with a mixed clinical picture, imaging can be used to exclude other pathologies and confirm the diagnosis. Hip X-ray is a useful first-line investigation in primary care;2 in patients with clinical symptoms and signs of GTPS this investigation is usually normal, but can exclude common differentials including osteoarthritis of the hip and fractures.2

Ultrasound and MRI are useful second-line investigations to confirm the diagnosis. Diagnostic ultrasound is an imaging modality with a high PPV for diagnosis of GTPS.2 Positive findings include fluid-filled and thickened trochanteric bursa with evidence of inflammation, tendinopathic echogenic findings, or tears within the gluteus medius or gluteus minimus tendons.2,4 MRI is best utilised in secondary care settings.2 MRI changes are commonly found in asymptomatic patients so interpretation of results must be clinically correlated.7

TREATMENT

Optimal management of GTPS remains unclear, but the main goals of treatment should be to manage load and reduce compressive forces across greater trochanter, strengthen gluteal muscles, and treat comorbidities.

The majority of cases of GTPS can be successfully managed in primary care with weight loss, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), targeted physical therapy, load modification, and optimisation of biomechanics. Recalcitrant cases may require onward referral to musculoskeletal experts such as a sport and exercise medicine physician, enabling further investigation and specialist management. Adjunct therapies include shock wave therapy and therapeutic ultrasound. Corticosteroid injection (CSI) can be effective in recalcitrant cases. Surgical intervention is reserved only for failed conservative management.

In the acute phase, pain can be managed with rest, ice, soft tissue therapy, taping, and medications (NSAIDs and/or paracetamol). Runners should avoid banked tracks or roads with excess camber.4

Exercise and load management are the cornerstone of an effective tendinopathy management.6 Physical therapy should be tailored to the individual patient and have a specific focus during the early stages on gluteal strength and control, and then, as hip control improves, muscle strengthening should target the hip abductors.1,4 In addition, lumbopelvic postural control is vital to optimise biomechanics. To reduce compressive loads on the gluteal tendons, positions of excessive hip adduction (such as crossing legs and ITB stretching exercises) should be avoided, and at night patients can sleep with one or two pillows between their legs.4

CSIs provide effective short-term analgesia in 70–75% of cases, although at 12 months clinical trials show no difference in outcome to a watch and wait approach.1,4,6 A non-randomised trial compared CSI (75 patients) with a home exercise programme (76 patients); the success rates at 1 month were 75% and 7% respectively, but by 15 months were 48% for CSI and 80% for the home exercise group, highlighting only short-term benefits of CSI.8 When used, CSI should provide an analgesic window in which the patient can fully engage with an effective rehabilitation programme involving targeted physiotherapy, load modification, and postural control.4

Shock wave therapy has some promising results for its use in the treatment of GTPS;4 however, due to a paucity of research evidence the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) only recommends its use under special circumstances.1 Further research is needed to determine the role for therapeutic ultrasound.

Surgical treatment for GTPS is reserved for recalcitrant cases that have failed optimal conservative management, and functional outcomes are generally good.9 Procedures are dependent on underlying pathology but may involve lengthening or release of the ITB and fascia lata, gluteal tendon tear repair, minimally invasive endoscopic bursectomy, or open reduction trochanteric osteotomy.2

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Barratt PA, Brookes N, Newson A. Conservative treatments for greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(2):97–104. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowdhury R, Naaseri S, Lee J, Rajeswaran G. Imaging and management of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90(1068):576–581. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lievense A, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Schouten B, et al. Prognosis of trochanteric pain in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(512):199–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brukner P, Khan K. Brukner and Khan’s clinical sports medicine. North Ryde, NSW: McGraw-Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimaldi A, Mellor R, Nicolson P, et al. Utility of clinical tests to diagnose MRI-confirmed gluteal tendinopathy in patients presenting with lateral hip pain. Br J Sports Med. 2016;51(6):519–524. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellor R, Grimaldi A, Wajswelner H, et al. Exercise and load modification versus corticosteroid injection versus ‘wait and see’ for persistent gluteus medius/minimus tendinopathy (the LEAP trial): a protocol for a randomised clinical trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:196. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1043-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fearon AM, Scarvell JM, Neeman T, et al. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: defining the syndrome. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(10):649–653. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rompe JD, Segal NA, Cacchio A, et al. Home training, local corticosteroid injection, or radial shock wave therapy for greater trochanter pain syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1981–1990. doi: 10.1177/0363546509334374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Buono A, Papalia R, Khanduja V, et al. Management of the greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2012;102:115–131. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]