Abstract

A new ruthenium complex catalyzes the amination of primary and secondary alcohols and the regioselective mono- and sequential diamination of diols via the borrowing hydrogen pathway. Several variations on new intra- and intermolecular cyclizations of aminoalcohols, diols and diamines lead to heterocyclic ring systems.

Keywords: borrowing hydrogen, aminations, ruthenium(II) complex, heterocycle synthesis, hydrogen autotransfer

TOC Graphic

An air stable (phosphinoxazoline)Ru(II) complex efficiently catalyzes the 1:1 alcohol:amine amination of primary and secondary alcohols, the regioselective mono- and sequential diamination of diols, and several variants of new intra- and intermolecular BH cyclizations of aminoalcohols, diols and diamines.

INTRODUCTION

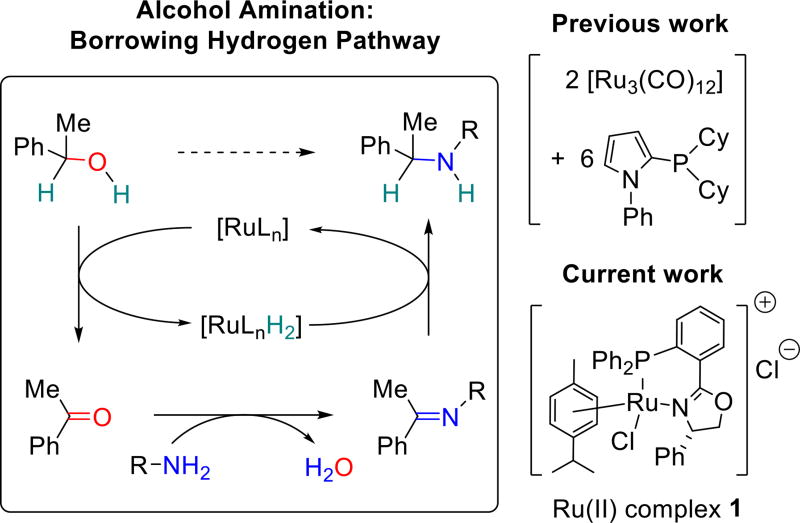

Alcohols are widely available starting materials for synthesis but typically require stoichiometric activation for use in classical substitution reactions. The direct substitution of alcohols by amines using transition metal catalysis, specifically methodology exploiting in situ activation via the “borrowing hydrogen” (BH) pathway1 (Figure 1), offers significant advantages over other substitution methods. The BH, also called hydrogen autotransfer, catalytic cycle involves initial metal-catalyzed dehydrogenation to form an intermediate carbonyl compound which undergoes addition-elimination with an amine to form the corresponding imine and water. Hydrogen generated in the dehydrogenation step reduces the imine to afford the desired alkylated amine product. Although formally a multi-step process, BH reactions are relatively “green”; they are atom efficient, carried out in one pot, and water is the sole by-product.

Figure 1.

Ruthenium-catalyzed amination of 1-phenylethanol via the BH method.

BH amidations2 and aminations are typically catalyzed by ruthenium3 or iridium4 complexes and less commonly by other transition metal complexes.5 The scope of ruthenium-catalyzed BH amination could be significantly improved by the development of catalyst systems that require lower catalyst loading, exhibit broader substrate scope, avoid the need for a large excess of either the alcohol or the amine and operate at more moderate temperatures and with shorter reaction times.2 We are particularly interested in developing ruthenium catalysts that are broadly effective for the amination of secondary alcohols, an aspect that remains underdeveloped in comparison to the facile aminations of primary alcohols.

Beller and co-workers3a–c reported the first efficient ruthenium catalysts for the amination of secondary alcohols in a ground-breaking series of reports beginning in 2006. A prototypical secondary alcohol substrate, 1-phenylethanol, gives high yields of amine products with simple aliphatic amines using ruthenium(0) dodecacarbonyl (Ru3CO12) in combination with 1-phenyl-2-dicyclohexylphosphinopyrrole (6 mol% Ru, 2–5:1 alcohol:amine), but not with a simple arylamine such as aniline.3b Williams and co-workers reported several examples of secondary alcohol amination using 2.5 mol % dichloro(p-cymene)ruthenium(II) dimer and bis(2-diphenylphosphinophenyl)ether (DPEphos) ligand.3g The latter combination affords a quite versatile and efficient BH catalyst system. However, high conversions with simple secondary alcohols are generally achieved only under xylene reflux conditions for (5 mol% Ru, 150 °C, 24 h). In the present work, the air-stable ruthenium(II) complex 1 was found to promote high conversion of both aliphatic and aromatic amines with 1-phenylethanol (and a variety of more complex alcohols) using 2.0% or lower catalyst loading and a 1:1 ratio of alcohol to amine.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

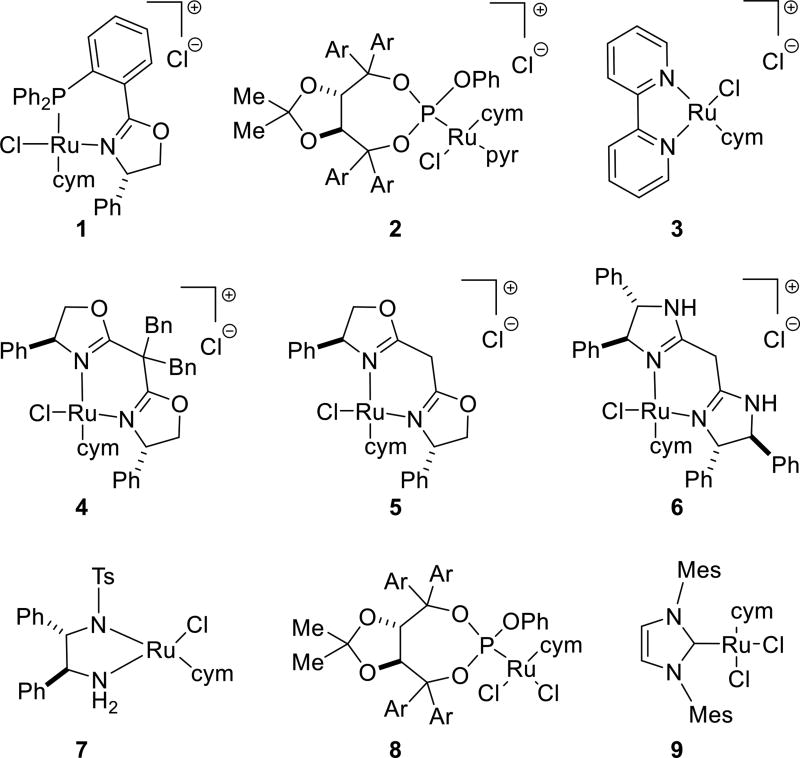

Complex 1 was among a series of ruthenium complexes prepared from dichloro(p-cymene)ruthenium(II) dimer and a small but quite varied set of chelating and non-chelating ligand systems (Figure 2). Our study was intended to quickly assay how factors such as sterics, electronics, neutral versus anionic ligands, neutral versus cationic catalyst precursors, and coordinating versus non-coordinating counterions affect the outcome in a series of model reactions of secondary alcohols with primary amines. In addition to the phosphinooxazoline6a complex 1, complexes incorporating bisoxazoline,6b TADDOL-derived phosphite,6c,d bipyridine,6e and IMes-NHC6f ligands were prepared. Complexes 3,6e 7,6g and 96f are known; however, their use for the amination of secondary alcohols has to the best of our knowledge not been reported. The simple chiral ligands were included in our study to evaluate the potential for asymmetric induction, although in no case was significant induction realized.

Figure 2.

Ru(II) complexes 1–9 incorporate chelating and non-chelating ligand systems (cym = p-cymene; pyr = pyridine; Ar = 3,5-dimethylphenyl).

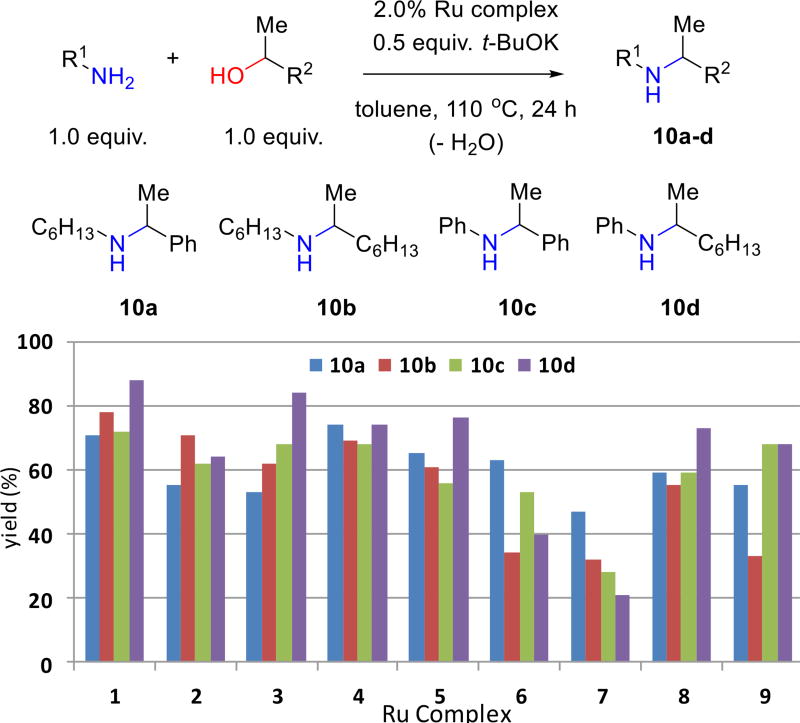

After arriving at a suitable set of initial reaction conditions, complexes 1–9 were individually screened in model reactions combining a secondary benzylic or non-benzylic alcohol (i.e., 1-phenylethanol and 2-octanol) with an aliphatic or aromatic amine (i.e., n-hexylamine and aniline); products 10a–d are formed (Figure 3). Cationic complexes with coordinated ligands that are not readily deprotonated (e.g., 1–4) generally afford more efficient catalysts. Several complexes (e.g., 3) work well in some reactions but not others, while others (e.g., 7) proved surprisingly poor under the reaction conditions used. Complex 1 gives yields in the range of 72–88% for the four substrate combinations. It is the overall most efficient catalyst precursor and therefore selected for further study.

Figure 3.

Use of complexes 1–9 for the preparation of amines 10a–d; yields are the average of two runs on the scale of 0.6 mmol each of amine and alcohol.

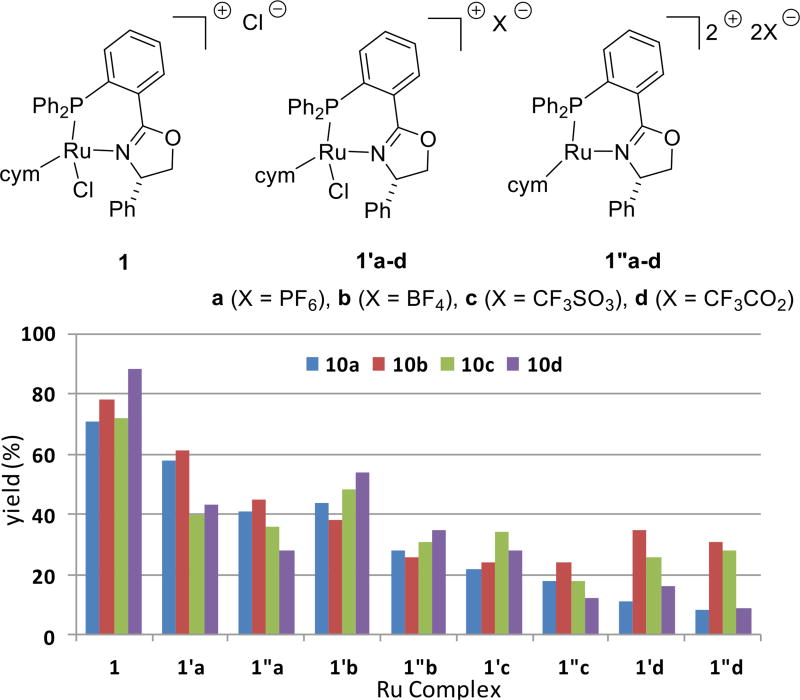

The reactivity of cationic complexes led us to study analogues of 1 in which one or two chlorides were replaced by more weakly coordinating counter-anions via silver-mediated exchange (i.e., complexes 1'a–d and 1"a–d, respectively) (Figure 4). Complexes 1'a–d were generally more effective than the corresponding complexes 1"a–d but none of the anion-exchanged catalysts are as effective as complex 1. Complexes in which chloride is exchanged for triflate or trifluoroacetate are found to be particularly ineffective catalyst precursors.

Figure 4.

The effect of exchanging counteranion on the percent yield of 10a–d.

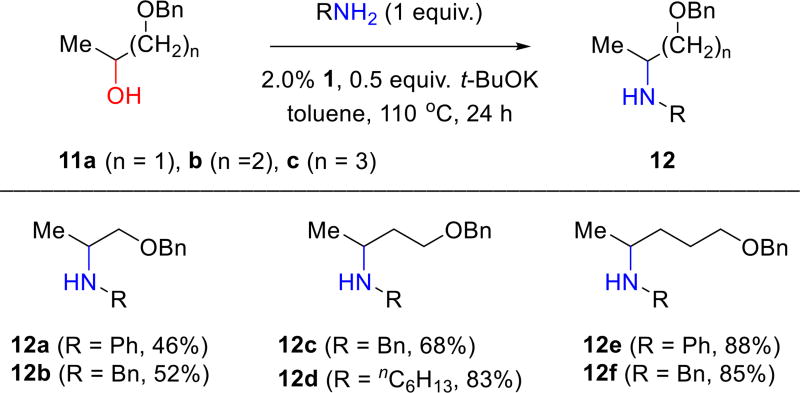

Complex 1 is applicable to representative examples for a wide variety of the common applications of BH for amine synthesis, including aminations of a variety of primary and secondary alcohols, some diols, and several intra- and intermolecular cyclizations of secondary aminoalcohols, amines and diols. For example, complex 1 catalyzes the amination of secondary alcohols 11a–c with aniline, benzylamine, and n-hexylamine (Figure 5). Products 12a–f are obtained in good yields without using an excess of either the amine or alcohol (1:1 ratio used).

Figure 5.

Aminations of secondary alcohols 11a–c using complex 1.

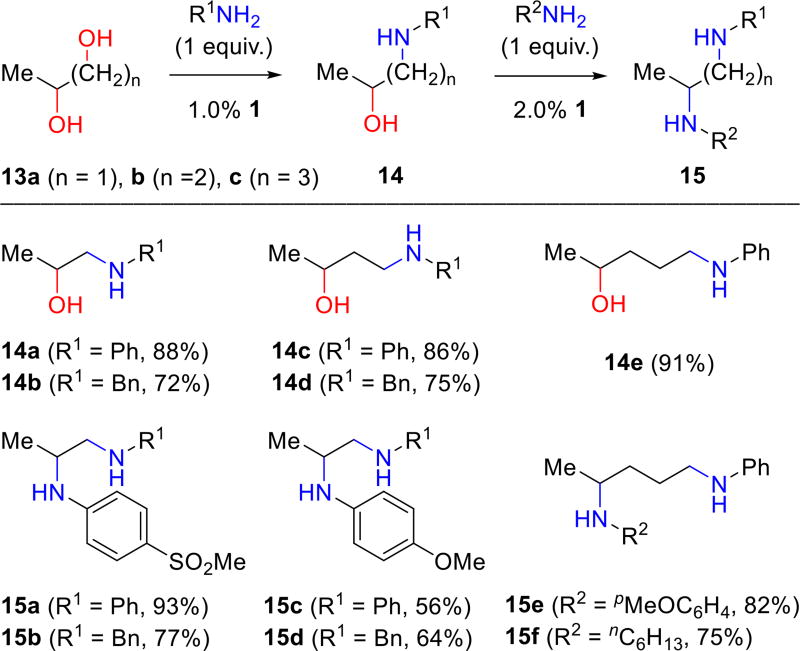

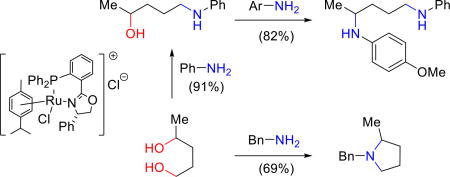

Primary alcohols also undergo efficient amination with complex 1. Their reactions are significantly faster as illustrated by the regioselective aminations of 1,2-propanediol (13a), 1,3-butanediol (13b) and 1,4-pentanediol (13c) by one equivalent of aniline or benzylamine. The corresponding aminoalcohols 14 were obtained in high yields and with excellent regioselectivity (Figure 6); 1.0% of complex 1 is sufficient for efficient conversion. Beller and co-workers had previously reported the regioselective amination of 1-phenyl-1,2-ethanediol [(2 mol % Ru3CO12 and N-phenyl-2-(dicyclohexyl-phosphanyl)pyrrole (CataCXium PCy)], although the maximum yield reported with aniline was 55%.7 Similarly, Oe reported the regioselective amination of 1-phenyl-1,2-ethanediol with secondary amines (5 mol% Ru and (S,R)-Josiphos).8

Figure 6.

Regioselective mono- and sequential diaminations of diols 13a–c.

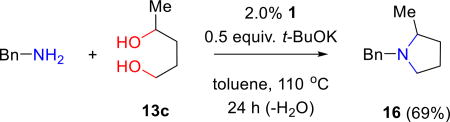

The isolated aminoalcohols 14a, 14b, and 14e are subsequently used to synthesize diamines 15a–f by reaction of the secondary alcohol. It is again noteworthy that the second amination is successful for both aliphatic and aromatic amines. Furthermore, the data illustrate that moderate electron withdrawing or donating substituents in the arylamine reactant are well tolerated. The formation of simple nitrogen heterocycles from the condensation of diols with amines via BH is well-precedented. We find the 1:1 reaction of benzylamine with 1,4-pentanediol (13c) leads to the formation of N-benzyl-2-methylpyrrolidine (16) in good yield (69%).

|

(1) |

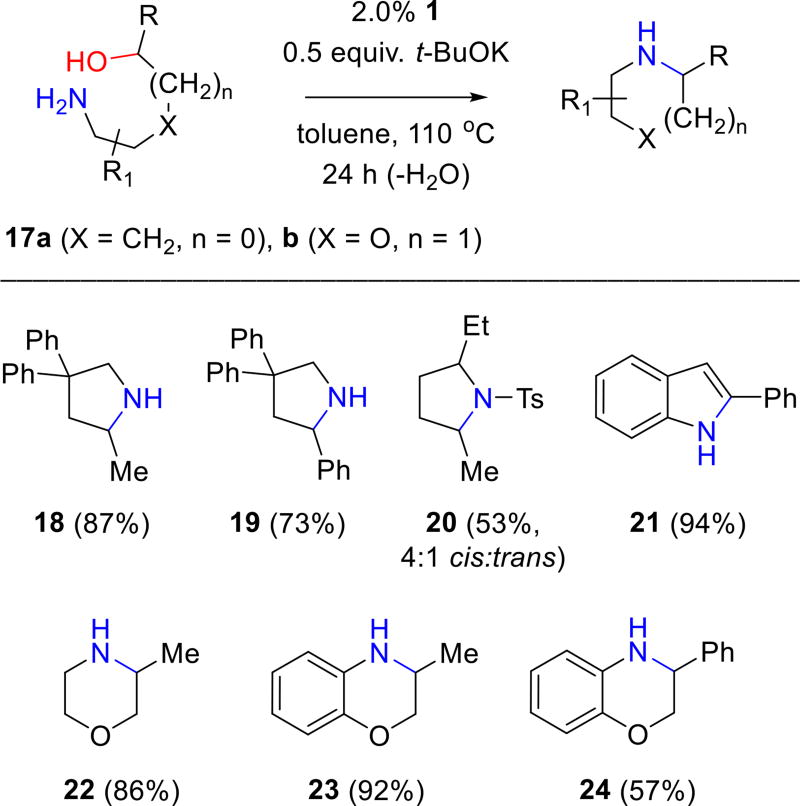

Figure 7 shows other examples of five- and six-membered heterocycle formation via BH cyclizations of aminoalcohols 17.9 Appropriately substituted derivatives of 17a cyclize to 2,4,4-trisubstituted pyrrolidines 18 and 19 and to the 2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidine 20; the latter, isolated as its sulphonamide derivative, is produced as a 4:1 mixture of cis- to trans-diastereomers. 2-Phenylindole (21) is produced in excellent yield (94%) from its aminoalcohol precursor; however, likely due to its aromaticity, the BH reaction stops at the indole stage rather than undergoing further reduction. The formation of indoles from primary and secondary aminoalcohols has previously been reported via iridium-catalyzed BH methodology.4a Our report here is to the best of our knowledge the first complementary example using a ruthenium catalyst. Other multicomponent dehydrogenative condensations leading to aromatic nitrogen heterocycles (e.g., pyrroles, pyridines and pyrimidines) have been reported by Kempe,10 Milstein11 and Beller.12 Complex 1 also affords six-membered ring saturated heterocycles, i.e., 2-methylmorpholine (22) and dihydrobenzoxazine derivatives 23 and 24, from appropriately substituted aminoalcohols possessing the core structure illustrated by 17b.

Figure 7.

Synthesis of five- and six-membered heterocycles via ruthenium-catalyzed BH cyclizations of aminoalcohols using complex 1.

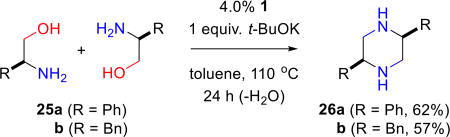

Chiral piperazines are useful building blocks for the total synthesis of biologically active compounds13 and have been used in the design of flexible ligands for self-assembled coordination polymers.14 The iridium-catalyzed cyclodimerization of ethanolamine derivatives was reported by Yamaguchi and co-workers.15 We report what we believe are the first examples in which ruthenium-catalyzed BH methodology is used to cyclodimerize readily available chiral aminoalcohols. (S)-Phenylglycinol (25a) and (S)-phenylalaninol (25b) dimerize to give chiral cis-2,5-disubstituted piperazines in good yield (eq 2). We see no evidence for epimerization at the stereocenter alpha to nitrogen during the course of reaction; piperazines 26a and 26b are essentially single enantiomers as judged by chiral HPLC analysis.

|

(2) |

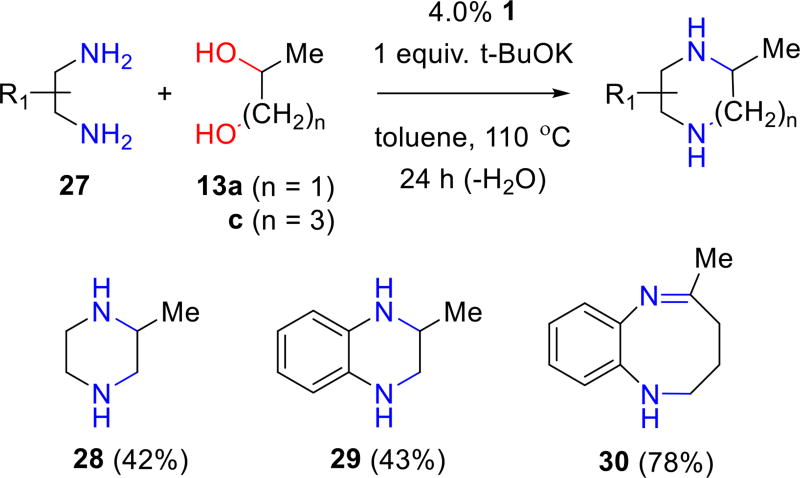

The cross-coupling of diamines with diols provides another route to piperazines (Figure 8). Iridium-catalyzed cyclocondensations of vicinal diamines with vicinal diols was reported by Madsen and co-workers.16 While it may be possible to further optimize the reaction conditions, BH cyclization using complex 1 using the standard conditions is thus far only moderately efficient; 2-methylpiperazine (28) and tetrahydroquinoxaline 29 are obtained in ca. 40% yield from the reaction of 1,2-propanediol (13a) with the requisite diamine. In contrast, the reaction of 1,4-pentanediol (13c) 1,2-phenylenediamine forms the 8-membered ring in 1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[b][1,4]diazocine derivative 30 in much higher yield (78%). However, the BH cyclodimerization stops short of producing the fully reduced product.

Figure 8.

Synthesis of piperazines and diazocines.

CONCLUSION

In summary, ruthenium(II) complex 1 efficiently catalyzes the BH amination of a variety of primary and secondary alcohols with alkyl and aryl amines, including the regioselective mono- and sequential diamination of diols. Several variants of intra- and intermolecular BH cyclizations of aminoalcohols, diols and diamines are also demonstrated. The latter lead to five- and six-membered ring heterocycles and in one case an eight-membered ring heterocycle.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

NMR spectra were recorded on 300 MHz or 700 MHz Bruker Avance III HD NMR spectrometers using residue CDCl3 (δ 7.26 ppm) or H2O (d 1.56 ppm) for 1H NMR reference. The central CDCl3 resonance (δ 77.16 ppm) is used as the 13C NMR reference. 1H NMR spectra are reported as follows (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, m = unresolved multiplet). Chiral HPLC analyses were performed on an ISCO model 2360 HPLC with Daicel chemical industries, LTD. Chiralcel OJH and Chiralpak AD or IC columns (0.46 × 25 cm). Data were recorded and analyzed with ChromPerfect chromatography software (version 5.1.0). IR spectra were recorded using an Avatar 360 FT-IR. Optical rotations were measured as solutions in dichloromethane or chloroform, and recorded using an Autopol III automatic polarimeter; the concentration, c, is reported in g/100 mL.

Chloro(p-cymene)[(S)-2-(2-(diphenylphosphanyl)-phenyl)-4-phenyl-4,5-dihydrooxazole]ruthenium(II) chloride (1)

A mixture of dichloro(p-cymene)-ruthenium(II) dimer 61 mg (0.10 mmol), (S)-2-(2-(diphenylphosphanyl)phenyl)-4-phenyl-4,5-dihydrooxazole 81 mg (0.20 mmol) in 10 mL of methanol was stirred at room temperature for 3 h. The solvent was evaporated. Flash chromatography on silica gel affords the ruthenium(II) complex 1 (128 mg, 90%) as orange solid: mp 116–118 °C; Rf = 0.4 (dichloromethane/methanol 9:1); [α]D25 = +183.8 (c 0.67, CH2Cl2); 1H NMR (700 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.15 (dd, J = 9.8, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (dd, J = 10.5, 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.62-7.54 (m, 12H), 7.48-7.42 (m, 2H), 7.38-7.35 (m, 2H), 6.31 (dd, J = 7.0, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 5.70 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, 1H), 5.56 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 4.95 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 4.61 (dd, J = 9.1, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 2.67 (septet, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H), 1.17 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 0.80 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (175 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.8 (d, J = 5.3 Hz), 139.4, 134.0, 133.9, 133.4, 133.3, 132.1, 131.7, 131.5, 129.5, 129.4, 129.3, 128.9, 128.8, 127.6, 76.6, 76.0, 31.0, 22.7, 20.1, 16.8 ppm; 31P NMR (283.4 MHz, CDCl3) δ 34.8 ppm; IR (neat) 3366, 3052, 2160, 2031, 1599, 1434, 1093, 729, 696 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C37H36NOP35Cl96Ru [(M-Cl)+], 672.1299; found, 672.1306 m/z.

Sample Procedure for the Reaction of a Secondary Alcohol: N-(1-Phenylethyl)hexan-1-amine (10a).3b,4f,5c,17

In a nitrogen-filled glovebox an 8 mL oven-dried sample vial was charged with a ruthenium(II) complex 1 (7.1 mg, 0.01 mmol, 2 mol %), 1-phenylethanol (61 mg, 0.50 mmol), n-hexylamine (51 mg, 0.50 mmol), and potassium tert-butoxide (28 mg, 0.25 mmol). Toluene (1 mL) was added and the vial sealed with a teflon-lined septum/screw cap. The reaction mixture was taken outside the glovebox and heated to 110 °C for 24 h after which the mixture was cooled to room temperature. Water (5 mL) was added and the mixture extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL). The combined organics were dried (anhyd Na2SO4), and the solvent was removed under vacuum. Purification by flash chromatography on silica gel afforded compound 10a (73 mg, 71%) as pale yellow liquid: Rf = 0.4 (hexanes/dichloromethane 1:1); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.35-7.30 (m, 4H), 7.28-7.23 (m, 1H), 7.20 (s, 2H), 3.78 (q, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 2.56-2.40 (m, 2H), 1.61 (br s, 1H), 1.54-1.43 (m, 2H), 1.38 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.34-1.24 (m, 6H), 0.89 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.9, 128.4, 126.8, 126.6, 58.4, 47.9, 31.8, 30.3, 27.1, 24.3, 22.6, 14.1 ppm.

Sample Procedure for the Reaction of a Primary Alcohol: N-(1-(benzyloxy)propan-2-yl)aniline (12a)

To a nitrogen-flushed flask equipped with reflux condenser was added 1 (25.7 mg, 0.036 mmol), 1-(benzyloxy)propan-2-ol 11a (300 mg, 1.80 mmol), aniline (168 mg, 1.80 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (101 mg, 0.90 mmol). Toluene (4 mL) was added, and the resulting reaction mixture was heated and stirred (110 °C, 24 h). Afterwards, the mixture was cooled (RT) and partitioned with water (8 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 5 mL) and the combined organic layers dried (anhyd. Na2SO4), filtered and concentrated. Flash chromatography on silica gel afforded 12a (200 mg, 46%) as a light colored liquid: Rf = 0.45 (hexanes/dichloromethane 1:2); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39-7.31 (m, 5H), 7.19 (dd, J = 8.4, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 6.75 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 3.81 (br s, 1H), 3.78-3.68 (m, 1H), 3.60-3.48 (m, 2H), 1.29 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 147.4, 138.3, 129.3, 128.4, 127.7, 127.6, 117.3, 113.5, 73.5, 73.3, 48.4, 18.1 ppm; IR (neat) 2860, 2160, 2020, 1601, 1503, 1453, 1315, 1257, 1074, 745, 695 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C16H19NONa [(M+Na)+], 264.1364; found, 264.1354 m/z.

Procedure for the Reaction of a Diol: (Phenylamino)propan-2-ol (14a).18

To a nitrogen-flushed flask equipped with reflux condenser was added 1 (21.4 mg, 0.030 mmol), 1,2-propanediol (228 mg, 3.00 mmol), aniline (279 mg, 3.00 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (168 mg, 1.50 mmol). Toluene (5 mL) was added, and the resulting reaction mixture was heated and stirred (110 °C, 24 h). Afterwards, the mixture was cooled (RT) and partitioned with water (10 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 10 mL) and the combined organic layers dried (anhyd Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated. Flash chromatography on silica gel affords aminoalcohol 14a (399 mg, 88%) as an amber liquid: Rf = 0.5 (ethyl acetate/hexanes 1:1); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.22 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.77 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 4.09-3.99 (m, 1H), 3.25 (dd, J = 12.9, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (dd, J = 12.9, 8.7 Hz, 1H overlapping with br s, 2H), 1.28 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 148.3, 129.3, 117.9, 113.3, 66.4, 51.7, 20.9 ppm.

N4-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N1-phenylpentane-1,4-diamine (15e)

The general procedure (2 mol % 1) gave 15e (186 mg, 82%) as a pale amber oil: Rf = 0.4 (ethyl acetate/hexanes 1:2); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.21 (dd, J = 8.4, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.82 (dd, J = 6.6, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.64-6.57 (m, 4H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.47 (tq, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H overlapping with br s, 2H), 3.16 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 1.81-1.54 (m, 4H), 1.21 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.0, 148.4, 141.7, 129.3, 117.2, 115.0, 114.8, 112.7, 55.9, 49.4, 44.0, 34.7, 26.1, 21.0 ppm; IR (neat) 3385, 2960, 2844, 2024, 1605, 1518, 1312, 1305, 1231, 1034, 821, 751, 691 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C18H24N2ONa [(M+Na)+], 307.1786; found, 307.1793 m/z; calcd. for C18H25N2O [(M+H)+], 285.1967; found, 285.1965 m/z.

1-Benzyl-2-methylpyrrolidine (16).19a,b

The general procedure (2 mol % 1) gave 16 (145 mg, 69%) as a pale yellow oil: Rf = 0.3 (dichloromethane/methanol 4:1); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39-7.25 (m, 5H), 4.06 (d, J = 12.6 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 2.94 (td, J = 9.9, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (tq, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.14 (q, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 2.00-1.92 (m, 1H), 1.76-1.63 (m, 2H), 1.56-1.47 (m, 1H), 1.22 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.6, 129.1, 128.2, 126.8, 59.6, 58.4, 32.8, 21.5, 19.2 ppm; HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C12H18N [(M+H)+], 176.1440; found, 176.1431 m/z.

General Procedure for the BH Cyclization of Aminoalcohols 17a/b: 2,4,4-Triphenylpyrrolidine (19)

To a nitrogen-flushed flask equipped with reflux condenser was added 1 (14.3 mg, 0.020 mmol), the appropriate secondary aminoalcohol (1.00 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (56.0 mg, 0.500 mmol). Toluene (3 mL) was added, and the resulting reaction mixture was heated and stirred (110 °C, 24 h). Afterwards, the mixture was cooled (RT) and partitioned with water (5 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (2 × 5 mL), and the combined organic layers were dried (anhyd Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated. Flash chromatography on silica gel affords 19 (218 mg, 73%) as a pale yellow oil: Rf = 0.45 (ethyl acetate); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.43-7.16 (m, 15H), 4.35 (dd, J = 10.2, 6.9 Hz, 1H), 3.99 (dd, J = 11.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 3.63 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (ddd, J = 12.6, 6.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 2.46 (dd, J = 12.6, 10.2 Hz, 1H), 1.81 (br s, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 147.4, 146.4, 143.9, 128.6, 128.5, 128.3, 127.1, 127.0, 126.9, 126.4, 126.2, 126.1, 61.1, 58.4, 57.0, 48.0 ppm; IR (neat) 3807, 2926, 1493, 1445, 1032, 910, 752, 697 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) calcd. for C22H22N [(M+H)+], 300.1752; found, 300.1738 m/z.

3-Methyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazine (23)20a,b

The general procedure (2 mol % 1) gave 23 (137 mg, 92%) as a pale yellow oil: Rf = 0.4 (ethyl acetate/hexanes 1:3); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.83-6.75 (m, 2H), 6.71-6.60 (m, 2H), 4.21 (dd, J = 10.5, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (dd, J = 10.5, 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (br s, 1H), 3.62-3.51 (m, 1H), 1.21 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.6, 133.4, 121.3, 118.8, 116.5, 115.4, 70.7, 45.2, 17.8 ppm.

General Procedure for the BH Self-Dimerization of Chiral Aminoalcohols: (2S,5S)-2,5-Diphenyl-piperazine (26a)

A condenser equipped flask with a mixture of 1 (57.0 mg, 0.080 mmol), chiral aminoalcohol (2.00 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (224 mg, 2.00 mmol) was degassed and flushed with nitrogen. Toluene (5 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 110 °C for 24 h. The reaction mixture was cooled (RT) and DCM (8 mL) added. The resulting suspension was filtered through celite, and the solvents evaporated. Flash chromatography on silica gel afforded 26a (148 mg, 62%) as a yellow oil: Rf = 0.35 (methanol); [α]D25 = +54.6 (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.42-7.26 (m, 10H), 4.00 (dd, J = 12.6, 10.8 Hz, 2H), 3.27 (dd, J = 12.6, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.14 (dd, J = 12.6, 8.1 Hz, 2H), 2.12 (br s, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 142.8, 128.2, 127.6, 127.0, 57.8, 49.1 ppm; IR (neat) 3323, 3019, 2701, 1460 cm−1; HRMS (EI) calcd. for C16H18N2 [M+], 238.1470; found, 238.1476 m/z.

General Procedure for BH Condensation of Diamines with Diols: 5-Methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[b][1,4]-diazocine (30)

A condenser equipped flask with a mixture of 1 (34.3 mg, 0.048 mmol), diol (1.20 mmol), diamine (1.20 mmol) and potassium tert-butoxide (135 mg, 1.20 mmol) was degassed and flushed with nitrogen. Toluene (4 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 110 °C for 24 h. After cooling (RT), DCM (5 mL) was added, and the resulting suspension was filtered through celite. Flash chromatography on silica gel afforded 30 (163 mg, 78%) as a sticky brown oil: Rf = 0.3 (ethyl acetate/hexanes 1:2); 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.75-6.69 (m, 2H), 6.63-6.55 (m, 2H), 3.50-3.41 (m, 1H), 3.25-3.17 (m, 1H), 1.94-1.78 (m, 4H), 1.49 (s, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.4, 141.2, 121.1, 120.3, 112.0, 109.5, 88.8, 54.4, 39.5, 28.7, 24.5 ppm; IR (neat) 2961, 2872, 1585, 1487, 1295, 1232, 718 cm−1; HRMS (EI) calcd. for C11H14N2 [M+], 174.1157; found, 174.1164 m/z.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NIH (NIGMS R01 GM100101) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Nebraska Center for Mass Spectrometry for HRMS analyses.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information Available: experimental details for the synthesis and characterization of starting materials and final compounds, copies of 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of all compounds, and relevant HPLC traces. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.For reviews and highlights on borrowing hydrogen methodology, see: Hamid MHSA, Slatford PA, Williams JMJ. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:1555–1575.Dobereiner GE, Crabtree RH. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:681–703. doi: 10.1021/cr900202j.Guillena G, Ramón DJ, Yus M. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1611–1641. doi: 10.1021/cr9002159.Watson AJA, Williams JMJ. Science. 2010;329:635–636. doi: 10.1126/science.1191843.Bähn S, Imm S, Neubert L, Zhang M, Neumann H, Beller M. ChemCatChem. 2011;3:1853–1864.Pan S, Shibata T. ACS Catal. 2013;3:704–712.Moseley JD, Murray PM. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2014;89:623–632.Yang Q, Wang Q, Yu Z. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:2305–2329. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00496e.Leonard J, Blacker AJ, Marsden SP, Jones MF, Mulholland KR, Newton R. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2015;19:1400–1410.

- 2.(a) Prechtl MHG, Wobser K, Theyssen N, Ben-David Y, Milstein D, Leitner W. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2012;2:2039–2042. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gnanaprakasam B, Balaraman E, Gunanathan C, Milstein D. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2012;50:1755–1765. [Google Scholar]; (c) Srimani D, Balaraman E, Gnanaprakasam B, Ben-David Y, Milstein D. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354:2403–2406. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For selected examples of Ru-catalyzed amination of alcohols, see: Tillack A, Hollmann D, Michalik D, Beller M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:8881–8885.Hollmann D, Tillack A, Michalik D, Jackstell R, Beller M. Chem. – Asian J. 2007;2:403–410. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600391.Tillack A, Hollmann D, Mevius K, Michalik D, Bähn S, Beller M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008:4745–4750.Zhang M, Imm S, Bähn S, Neumann H, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:11197–11201. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104309.Hamid MHSA, Williams JMJ. Chem. Commun. 2007:725–727. doi: 10.1039/b616859k.Hamid MHSA, Williams JMJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:8263–8265.Hamid MHSA, Allen CL, Lamb GW, Maxwell AC, Maytum HC, Watson AJA, Williams JMJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:1766–1774. doi: 10.1021/ja807323a.Watson AJA, Maxwell AC, Williams JMJ. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:2328–2331. doi: 10.1021/jo102521a.Monrada RN, Madsen R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2011;9:610–615. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00676a.Yamaguchi K, He J, Oishi T, Mizuno N. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010;16:7199–7207. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000149.Agrawal S, Lenormand M, Martin-Matute B. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1456–1459. doi: 10.1021/ol3001969.Fernández FE, Puerta MC, Valerga P. Organometallics. 2012;31:6868–6879.Enyong AB, Moasser B. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79:7553–7563. doi: 10.1021/jo501273t.Balaraman E, Srimani D, Diskin-Posner Y, Milstein D. Catal. Lett. 2015;145:139–144.

- 4.For selected examples of Ir-catalyzed amination of alcohols, see: Fujita K, Yamamoto K, Yamaguchi R. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2691–2694. doi: 10.1021/ol026200s.Fujita K, Fujii T, Yamaguchi R. Org. Lett. 2004;6:3525–3528. doi: 10.1021/ol048619j.Fujita K, Enoki Y, Yamaguchi R. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:1943–1954.Kawahara R, Fujita K, Yamaguchi R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:15108–15111. doi: 10.1021/ja107274w.Kawahara R, Fujita K, Yamaguchi R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011;353:1161–1168.Prades A, Corberan R, Poyatos M, Peris E. Chem. – Eur. J. 2008;14:11474–11479. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801580.Blank B, Madalska M, Kempe R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:749–758.Blank B, Michlik S, Kempe R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:2903–2911.Blank B, Michlik S, Kempe R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2009;15:3790–3799. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802318.Michlik S, Kempe R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2010;16:13193–13198. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001871.Michlik S, Hille T, Kempe R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354:847–862.Ruch S, Irrgang T, Kempe R. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014;20:13279–13285. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402952.Gnanamgari D, Sauer ELO, Schley ND, Butler C, Incarvito CD, Crabtree RH. Organometallics. 2009;28:321–325.Saidi O, Blacker AJ, Farah MM, Marsden SP, Williams JMJ. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:1541–1543. doi: 10.1039/b923083a.Cumpstey I, Agrawal S, Borbas EK, Martin-Matute B. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:7827–7829. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12800k.Bartoszewicz A, Marcos R, Sahoo S, Inge AK, Zou X, Martin-Matute B. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012;18:14510–14519. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201845.Li J-Q, Andersson PG. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:6131–6133. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42669f.Zhang Y, Lim C-S, Sim DSB, Pan H-J, Zhao Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:1399–1403. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307789.Rong Z-Q, Zhang Y, Chua RHB, Pan H-J, Zhao Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4944–4947. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02212.Berliner MA, Dubant SPA, Makowski T, Ng K, Sitter B, Wager C, Zhang Y. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2011;15(5):1052–1062.

- 5.For selected examples of Cu, Pd, Fe, and Co-catalyzed amination of alcohols, see: Shi F, Tse MK, Cui X, Gordes D, Michalik D, Thurow K, Deng Y, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:5912–5915. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901510.Martinez-Asencio A, Ramon DJ, Yus M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:325–327.Dang TT, Ramalingam B, Shan SP, Seayad AM. ACS Catal. 2013;3:2536–2540.Pan H-J, Ng TW, Zhao Y. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:11907–11910. doi: 10.1039/c5cc03399c.Röçsler S, Ertl M, Irrgang T, Kempe R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:15046–15050. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507955.

- 6.(a) Tang X, Zhang D, Jie S, Sun W, Chen J. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005;690:3918–3928. [Google Scholar]; (b) Burguete MI, Fraile JM, Garcia JI, Garcia-Verdugo E, Luis SV, Mayoral JA. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3905–3908. doi: 10.1021/ol0066633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith SM, Thacker NC, Takacs JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3734–3735. doi: 10.1021/ja710492q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith SM, Takacs JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1740–1741. doi: 10.1021/ja908257x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lalrempuia R, Kollipara MR, Carroll PJ, Yap GPA, Kreisel KA. J. Organomet. Chem. 2005;690:3990–3996. [Google Scholar]; (f) Ledoux N, Allaert B, Verpoort F. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007:5578–5583. [Google Scholar]; (g) Ikariya T, Hashiguchi S, Murata K, Noyori R. Org. Synth. 2005;82:10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bähn S, Tillack A, Imm S, Mevius K, Michalik D, Hollmann D, Neubert L, Beller M. ChemSusChem. 2009;2:551–557. doi: 10.1002/cssc.200900034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putra AE, Oe Y, Ohta T. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013:6146–6151. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The aminoalcohols used were synthesized via standard routes; see the Supporting Information.

- 10.(a) Michlik S, Kempe R. Nature Chem. 2013;5:140–144. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Michlik S, Kempe R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:6326–6329. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Forberg D, Obenauf J, Friedrich M, Hühne S-M, Mader W, Motz G, Kempe R. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014;4:4188–4192. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hille T, Irrgang T, Kempe R. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:5569–5572. doi: 10.1002/chem.201400400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Deibl N, Ament K, Kempe R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:12804–12807. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b09510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Srimani D, Ben-David Y, Milstein D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:4012–4015. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Srimani D, Ben-David Y, Milstein D. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:6632–6634. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43227k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Zhang M, Fang X, Neumann H, Beller M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11384–11388. doi: 10.1021/ja406666r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang M, Neumann H, Beller M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:597–601. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mordini A, Reginato G, Calamante M, Zani L. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2014;14(10):1308–1316. doi: 10.2174/1568026614666140423114013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu S-C, Wu J-Y, Lee C-F, Lee C-C, Lai L-L, Lu K-L. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2010;12:3388–3390. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujita K, Kida Y, Yamaguchi R. Heterocycles. 2009;77:1371–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorentz-Petersen LLR, Nordstrøm LU, Madsen R. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012:6752–6759. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson A, Abrahamsson P, Davidsson O. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:1261–1266. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang C, Chen J, Yu X, Chen X, Wu H, Yu J. Synth. Commun. 2008;38:1875–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Ackermann L, Kaspar LT, Althammer A. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:1975–1978. doi: 10.1039/b706301f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Julian LD, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13813–13822. doi: 10.1021/ja1052126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Bunce RA, Herron DM, Hale LY. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2003;40:1031–1039. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lopez-Iglesias M, Busto E, Gotor V, Gotor-Fernandez V. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:3815–3824. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.