Abstract

The stomach may be involved by a myriad of pathologies ranging from benign aetiologies like inflammation to malignant aetiologies like carcinoma or lymphoma. Multidetector CT (MDCT) of the stomach is the first-line imaging for patients with suspected gastric pathologies. Conventionally, CT imaging had the advantage of simultaneous detection of the mural and extramural disease extent, but advances in MDCT have allowed mucosal assessment by virtual endoscopy (VE). Also, better three-dimensional (3D) post-processing techniques have enabled more robust and accurate pre-operative planning in patients undergoing gastrectomy and even predict the response to surgery for patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for weight loss. The ability of CT to obtain stomach volume (for bariatric surgery patients) and 3D VE images depends on various patient and protocol factors that are important for a radiologist to understand. We review the appropriate CT imaging protocol in the patients with suspected gastric pathologies and highlight the imaging pearls of various gastric pathologies on CT and VE.

INTRODUCTION

Various pathologies like gastritis, carcinoma, lymphoma, carcinoid, metastases, bezoar or corrosive injury may affect the stomach. CT is usually the initial imaging investigation of choice for evaluation of these cases. Conventionally, CT could evaluate the mural and extramural extent of diseases and could not provide any mucosal information. Advances in the CT technology and three-dimensional (3D) post-processing software have enabled new exciting possibilities like CT-based endoscopic images [virtual endoscopy (VE)]1 as well as allowed accurate staging for neoplastic diseases of the stomach2 and predict the post-operative weight loss for patients undergoing bariatric surgery.3 It is very important for a radiologist to understand the appropriate gastric imaging protocol, since the acquisition of appropriate CT images requires patient fasting, adequate gastric distension and a negative intraluminal contrast agent. This article describes the basic principle and protocol for multidetector CT (MDCT) of the stomach and reviews the role of CT for the diagnosis of various gastric pathologies and post-operative surveillance.

CT TECHNIQUE

At our institute, the stomach protocol CT is typically utilized for patients who have a clinical suspicion of gastric pathology with symptoms of indigestion, intractable oesophageal reflux or weight loss and refuse conventional endoscopy or if endoscopy was technically limited. We also use stomach protocol CT for patients undergoing pre-operative planning for gastric surgery, patients who have pathology on conventional endoscopy and in patients with a history of gastrectomy undergoing a follow-up scan. CT of the stomach requires the patient to be fasting for at least 6 h. An intramuscular injection of 20 mg of hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan®; Boehringer Ingelhiem India Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India) is given approximately 10 min before the examination to inhibit gastric peristalsis. Thereafter, effervescent granules (containing sodium bicarbonate, citric acid, simethicone, flavour and sweetener; manufactured by Eskay Fine Chemicals, Mumbai, India) are given to these patients just before the scan for gastric distension and to obtain negative intraluminal contrast. A topogram is then obtained to ensure adequate gastric distension. Additional effervescent granules may be given if the stomach is not adequately distended. Invasive techniques like air insufflation via nasogastric tubes are seldom performed in our practice, since they are very uncomfortable for the patient and we could obtain adequate distension with oral effervescent agents in nearly all of the cases. If the patient refuses effervescent granules, then 1000–1500 ml of water is given orally to the patient approximately 15–30 min prior to the CT, since it allows gastric distension as well as detection of mucosal enhancement; however, VE image reconstruction is not possible after administration of water.

CT is obtained on a 128-slice MDCT scanner (Definition AS+, Siemens Medical System, Forcheim, Germany). An initial non-contrast prone scan of the upper abdomen (including the entire distended stomach) is obtained with parameters as follows: 100 kV, collimation 0.6 mm, pitch 1.5, rotation 0.5 s and automated milliampere modulation with reference setting of 90–150 mA. This was followed by CT of the abdomen and pelvis with an i.v. iodinated contrast (Iomeron 350; Imaging Products Pvt Ltd, Mumbai, India for Bracco, Milan, Italy) in supine position with 120 kV and otherwise same technical parameters. The contrast is usually injected via the antecubital vein at 3 ml s−1 through a 20-gauge needle using an automatic injector and acquisition is obtained from the diaphragmatic dome to the femoral trochanters in the portal venous phase (70 s). If water is given as oral contrast, then initial prone scanning is not performed, but an arterial phase imaging of the abdomen, 30 s after contrast injection, is initially performed followed by portal venous phase at 70 s. This is carried out for better detection of gastric mucosal pathologies, since virtual gastroscopy cannot be performed when water is used as an intraluminal contrast. The sagittal and coronal images of the data sets are always reconstructed. CT protocol for the stomach at our institute is highlighted in Table 1.

Table 1.

CT technique for gastric evaluation

| Patient preparation | Fasting—at least 6 h |

| Oral contrast—effervescent granules with a sip of water on the CT gantry table. If patient could not take granules, 1000–1500 ml of water 15–30 min prior to scan | |

| Hypotonia—20 mg of hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan, Boehringer Ingelhiem India Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India) | |

| Position | Initial non-contrast prone scan of abdomen after confirming gastric distension on topograma |

| Then supine scan after contrast administration from just above the diaphragm to greater trochanters of femur | |

| Contrast material | Iomeron 350 (Imaging Products Pvt Ltd, Mumbai, India for Bracco, Milano, Italy) |

| Amount and rate | 100 ml @ 3 cc s−1, followed by 40 ml of saline flush |

| Scan parameters | Section collimation—0.6 mm, pitch—1.5, 100 kV for prone scan and 120 kV for supine scan |

| Phase of acquisition | Arterial phase (30 s after contrast injection) for tumour staging and if patient received water for stomach distension |

| Portal venous phase (70 s after contrast injection) in all patients | |

| Reconstruction | 1-mm slices with 0.8-mm reconstruction interval of the abdomen of prone and supine scan for 3D reconstructions |

| 3 mm axial, coronal and sagittal of the supine scan | |

| 3D reconstructions | Transparent volume rendered reconstructions of stomach for pre-operative planning (with gastric volume, if needed) |

| Endoluminal virtual endoscopic assessment of supine and prone data sets |

3D, three-dimensional.

If patient did not take the effervescent granules, this step is not performed.

POST-PROCESSING TECHNIQUE: VIRTUAL ENDOSCOPY, GASTRIC VOLUME AND TRANSPARENCY RENDERING

We reconstruct the raw data set at 1-mm slice thickness with 0.8-mm interval for VE, transparency rendering or gastric volume calculation. The images are sent to a dedicated 3D workstation (Syngovia; Siemens Medical System). The supine and prone data sets are assessed by VE for the detection of mucosal lesions. If any lesion is suspected, then appropriate multiplanar reconstructions (MPR) may also be reconstructed. For gastric volume calculation and transparency rendering, manual contour mapping of the stomach is performed. The process of post-processing usually takes 15–20 min per patient and these 3D images (Figure 1) are interpreted in conjunction with the two-dimensional axial, coronal and sagittal images.

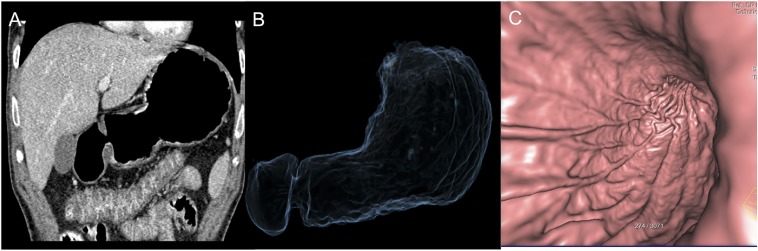

Figure 1.

Coronal CT (a), transparency rendering reconstruction (b) and CT gastroscopy (c) images showing the appearance of the normal stomach wall and fold pattern.

CT IMAGING OF GASTRIC PATHOLOGIES

CT is the most common imaging technique used for the diagnosis and staging of gastric diseases; however, its sensitivity and specificity varies in different diseases. The diagnostic accuracy of CT for gastric cancer varies with the stage of cancer. The accuracy for diagnosis of advanced gastric cancer (AGC) ranges between 90 and 100% when MPR and VE techniques are used,4,5 whereas the accuracy for diagnosis of early gastric cancer (EGC) varies from <20% with portal venous phase-only CT,4 88% after addition of an arterial phase scan6 and more than 95% with MPR and Virtual Endoscopy (VE).2,5 The evidence for EGC is limited by the number of studies and the number of cases in each study. Similarly, although CT is the most commonly used modality for the staging of gastric lymphoma, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), fludeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) and MRI are also utilized depending on availability and treating physician preference.7 These modalities are utilized either individually or in some combination, with increasing trend towards utilization of more than one modality. Overall, there is a lack of evidence and consensus for the use and primary diagnostic accuracy of CT for detecting important gastric pathologies. Various gastric diseases and their CT imaging features are described in the following section of this review.

Malignant diseases

Gastric cancer

Gastric adenocarcinoma is the commonest malignancy affecting the stomach, accounting for approximately 95% of overall malignant lesions of the stomach.8,9 The incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma has shown a persistent decline over years owing to various factors like global use of refrigeration and less reliance on salt for preservation and increased utilization of fresh fruits and vegetables, but it still accounts for approximately 10% of cancer-related deaths worldwide.10 The incidence of gastric cancer is highest in East Asia, Eastern Europe and South America with the affection of males approximately twice as that compared with females.10 The patient prognosis is based on the stage at which cancer is detected with 5-year survival of EGC ranging between 85 and 100% and AGC having 5-year survival of only 20%.11 Hence, accurate pre-operative staging is very important for treatment planning and patient prognosis.

Pathology, classification and staging

Various classification systems have been described for gastric cancer, based on gross appearance (Borrmann) or microscopic appearance (Lauren, World Health Organization, Ming).8 The commonly used histopathological classifications for gastric cancer are Lauren classification and the World Health Organization classification. The commonest gastric cancer histological subtype, adenocarcinoma, has two subtypes: diffuse and intestinal. The diffuse subtype is classically associated with signet ring-type cells, is more common in the young and has a diffuse infiltrative pattern (also called as linitis plastica). This type is relatively less affected by environmental factors and is associated with worse prognosis. The intestinal type is a result of metaplasia of cells and is usually mucin secreting.8 The Bormann classification that divides the tumour on the basis of relative exophytic and endophytic components (Figure 2) is also used to describe EGC lesions on CT (and VE).11 Based on the depth of wall involvement, gastric cancer is classified as early and advanced, with EGC signifying tumour limited to the mucosa and submucosa irrespective of lymph node involvement or distant metastases. As highlighted earlier, the patient prognosis with EGC is significantly better than that with AGC. The patient prognosis also depends upon the location of the tumour with worse prognosis of the proximal stomach cancers.12 Based on this observation, the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Gastric Cancer Staging System13 recommends using Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM) staging of oesophageal cancer for tumours arising at the oesophagogastric junction and for cancers involving the oesophagogastric junction but arising in the stomach 5 cm or less from the oesophagogastric junction. This is one of the major updates from the 6th edition of AJCC, as the previous classification of these tumours was based on the treating surgeon orientation and experience. Other updates in the 7th edition of AJCC for gastric tumour staging include harmonizing the T staging with oesophageal and large intestinal cancer staging (specific to gastric cancer TNM, the subserosa infiltration by the tumour, which was previously classified as T2b, is now classified as T3, and the perforation of serosa changed from T3 to T4a), classification of positive peritoneal cytology as M1 and modification of N categories and stage grouping (one of the prominent changes being that patients with only distant metastases are classified as stage IV). The N categories are now classified as N1 = 1–2 positive lymph nodes (as compared with 1–6 positive lymph nodes earlier), N2 = 3–6 positive lymph nodes (as compared with 7–15 positive lymph nodes earlier) and N3 = 7 or more positive lymph nodes (as compared with >15 positive lymph nodes earlier). These N categories are updated for both oesophageal and gastric cancers in the 7th edition of AJCC and now, except for subgrouping of N3 into N3a and N3b (which is not carried out for oesophageal cancer), the N categories of staging for both cancers are also similar.13,14 Overall, the 7th edition is shown to have better staging accuracy and patient prognostication with more explicit indications for treatment planning.14 The revised TNM staging for gastric cancer (7th edition) which applies to tumours arising in the more distal stomach and to tumours arising in the proximal 5 cm but not crossing the oesophagogastric junction is highlighted in Table 2.13 The staging of gastric cancer is best carried out with complementary use of EUS and CT. The depth of wall invasion and local lymph nodes are better assessed by the EUS, but its ability to detect distant spread is limited.15 Overall, the CT remains the most commonly used modality for the staging of gastric cancers. One of the studies showed that CT without stomach distension is better for detection of the perigastric fat, ligaments, lymph nodes and pancreas involvement, presumably owing to pseudo-obliteration of perigastric and peripancreatic fat planes upon distension,16 while multiple other CT-based studies with gastric distension showed excellent correlation of T and N staging when compared with post-operative surgical staging.17,18

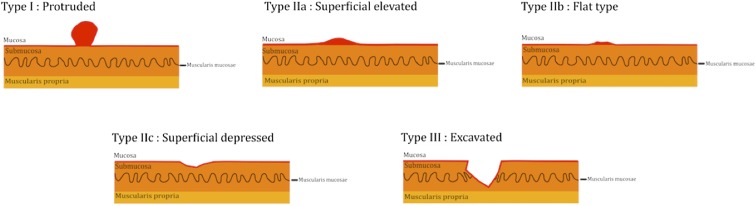

Figure 2.

An illustration diagram showing gross classification of early gastric cancers.

Table 2.

Revised TNM staging of gastric cancer13

| T category definitions | Gastric cancer |

| Tx | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumour |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial tumour without invasion of the lamina propria |

| T1 | Tumour invades lamina propria, muscularis mucosae or submucosa |

| T1a | Tumour invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosae |

| T1b | Tumour invades submucosa |

| T2 | Tumour invades muscularis propria |

| T3 | Tumour penetrates subserosal connective tissue without invasion of visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures. T3 tumours also include those extending into the gastrocolic or gastrohepatic ligaments, or into the greater or lesser omentum, without perforation of the visceral peritoneum covering these structures |

| T4 | Tumour invades serosa (visceral peritoneum) or adjacent structures |

| T4a | Tumour invades serosa (visceral peritoneum) |

| T4b | Tumour invades adjacent structures such as spleen, transverse colon, liver, diaphragm, pancreas, abdominal wall, adrenal gland, kidney, small intestine and retroperitoneum |

| N category definitions | Gastric cancer |

| Nx | Regional lymph node(s) cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in 1–2 regional lymph nodes |

| N2 | Metastasis in 3–6 regional lymph nodes |

| N3 | Metastasis in 7 or more regional lymph nodes |

| M category definitions | Gastric cancer |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis (including peritoneal cytology) |

Tumour detection and CT features

The detection of gastric cancer varies with the stage of cancer. Among the CT factors, many studies have shown better detection of gastric cancer with the use of water as a negative intraluminal contrast.19,20 Although conventional CT had >90% detection rate for AGC and elevated (or exophytic) EGC with negative intraluminal contrast agent, its role had been limited for depressed (or endophytic) EGC with detection of only 18% cases in the study by Hori et al.4 Improvement in the detection rates of EGC came with the use of dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging along with negative intraluminal contrast. These technical changes enabled better visualization of abnormal mucosal enhancement in the arterial phase. Kim et al6 showed detection of EGC in 88% of patients with arterial phase imaging. With the use of VE 3D technique, the detection of EGC by CT has improved further. A study by Kim et al2 showed a detection rate of 96% for EGC by complementary use of VE and conventional CT imaging. Another study by Bhandari et al5 found that CT (along with VE) was able to detect 96.7% of EGC and 100% of AGC. With VE, the detection of EGC is based on direct visualization of the abnormal area in the gastric mucosa rather than abnormal enhancement and it appear similar to conventional endoscopy. The Bormann classification is typically used to describe the lesion based on its morphologic characteristics.11 It has been shown that Virtual Endoscopy (VE) is as good as conventional endoscopy for differentiation of benign and malignant gastric ulcers.21,22

On conventional CT, the EGC appears as an elevated or depressed lesion that may show abnormal enhancement when the stomach is distended by the intraluminal negative contrast. The ulcerated EGC (Figure 3) may be associated with an abrupt cut-off of the gastric folds, clubbing or fusion of the folds at the margins of the ulcer and irregularity of the ulcer base.23 Virtual Endoscopy (VE) has shown very high detection rates (approximately 95%) for both elevated and depressed EGC.11,23 AGC (Figures 4 and 5), which is defined as tumour invading the muscularis propria, may be seen as large segmental/polypoidal or diffuse thickening that is often associated with ulceration. Sometimes, it may be difficult to distinguish normal soft-tissue thickening at the gastro-oesophageal junction (which occurs from the attachment and reflections of the phreno-oesophageal ligament and gastrohepatic ligament) from pathological thickening. Hence, distension of the stomach is required to prevent this pitfall.24

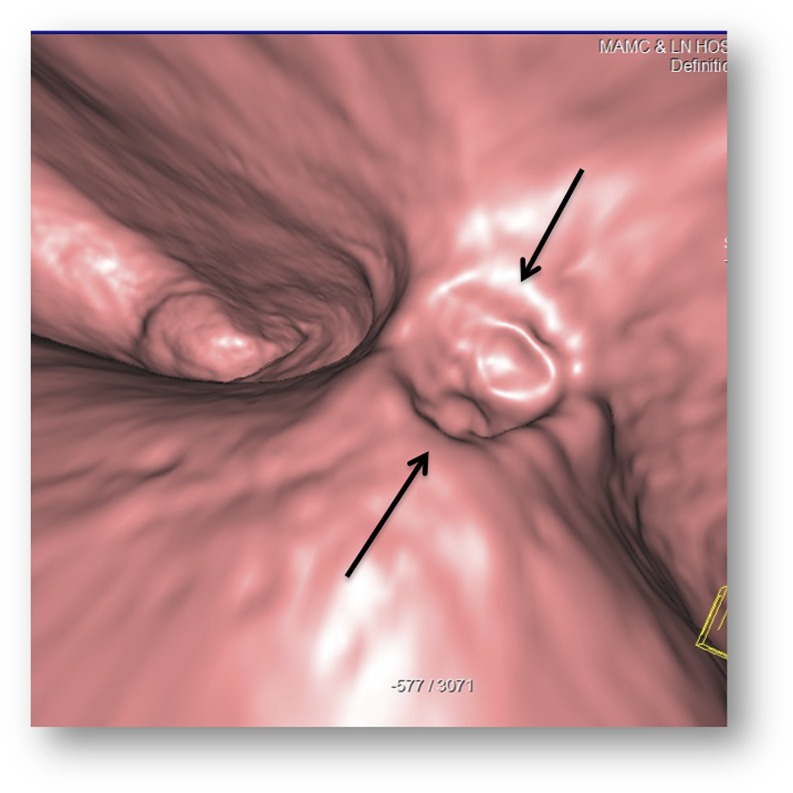

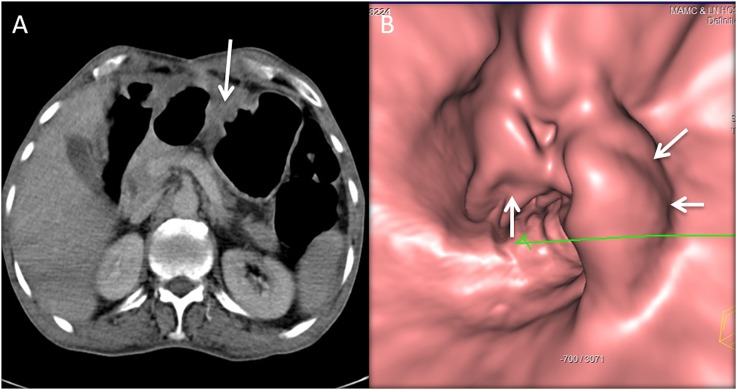

Figure 3.

A 62-year-old female with 15-lb weight loss and upper abdominal discomfort: the CT gastroscopy image is showing a 1-cm ulcer (arrows) with irregularity of the base at the lesser curvature, pathologically proven to be malignant ulcer.

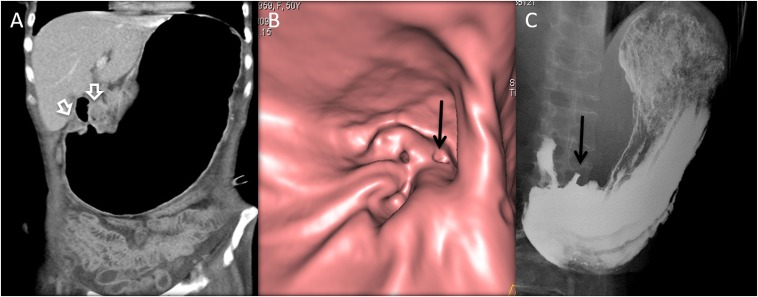

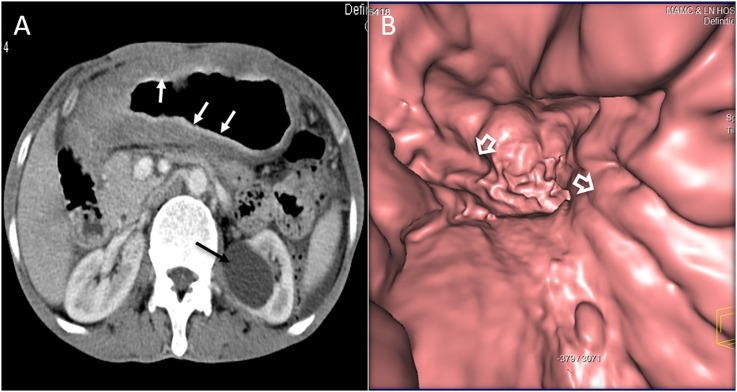

Figure 4.

A 50-year-old female with weight loss, abdominal pain and symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction: the coronal CT image (a) is showing the massively distended stomach with circumferential thickening of the distal antrum and pylorus (open white arrows). CT gastroscopy (b) is showing an ulceroproliferative mass near the pylorus with fold thickening. The barium upper gastrointestinal (c) is also showing the ulcer (black arrows in b and c) and stricture due to mass.

Figure 5.

A 69-year-old male with abdominal discomfort and weight loss: the axial CT image (a) is showing a mass lesion in the gastric body (arrow) projecting into the lumen. CT gastroscopy (b) is showing the surface characteristics of this irregular polypoidal mass lesion (arrows).

Gastric lymphoma

Gastrointestinal (GI) lymphoma is the commonest extranodal site of lymphoma with the stomach as the commonest site of GI lymphoma, affected in approximately 60–75% of cases.7 Overall, gastric lymphoma accounts for 3–5% of a total number of gastric malignancies, but unlike gastric cancer, the incidence of gastric lymphoma is increasing.7,25 Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, which is related to chronic Helicobacter pylori infection, comprises 50% of all primary lymphomas affecting the stomach, while diffuse large B-cell lymphoma accounts for nearly 40% cases of lymphoma. Rarely, other histological subtypes like T-cell lymphoma (associated with Human T-cell lymphotropic virus, type 1 (HTLV-1) infection) may be seen.7 Gastric lymphoma is more prevalent in males, usually affecting after 50 years of age. The patients typically present with epigastric pain, weight loss, nausea and vomiting. Given the “soft” cellular characteristics, gastric outlet obstruction is less common as compared with gastric cancer.9 The prognosis of patients varies with the histological subtype. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma is usually low grade and hence has a favourable outcome with a 5-year survival of 50–60%.7,24

The appearance on CT may be non-specific and common patterns include diffuse wall thickening, polypoidal mass, thickened folds or infiltrating lesions (Figure 6a). The common differential includes gastric cancer. CT features that favour gastric lymphoma include preserved gastric distensibility despite diffuse wall infiltration, involvement of more than one segment of the stomach, the presence of perigastric lymphadenopathy, greater wall thickening, preservation of fat planes with adjacent organs, transpyloric spread and the presence of lymphadenopathy below the renal hilum.7,26,27 To best of our knowledge, there has been no study to show the appearance of gastric lymphoma on VE; however, we found it helpful in our limited experience. Ulcerative gastric lymphoma or polypoidal lymphoma is well seen with VE. With VE, gastric distension is assessed, which is preserved in lymphoma, helping it differentiate from adenocarcinoma in which gastric distensibility is decreased or lost. Also, when the disease is diffusely infiltrative, the presence of “nodular” thickening of the gastric folds may also point towards lymphoma as possible aetiology of fold thickening (Figure 6b). CT is the primary imaging modality for pre-treatment evaluation and staging.24 Fluorine-18-FDG PET-CT may be challenging in these patients, as a small lesion may be obscured by the physiological uptake of FDG in gastric mucosa. The variability of FDG uptake with different histological subtypes can sometimes make it difficult to interpret.28

Figure 6.

A 66-year-old female with abdominal pain, fever and weight loss: the axial (a) CT is showing diffuse thickening of the stomach (white arrows) with relatively preserved distensibility. The left renal cyst is incidentally noted (black arrow). The CT gastroscopy image (b) is showing diffuse nodular gastric fold thickening (open arrows) in this patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour

Gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) is a mesenchymal tumour of the GI tract that arises from the interstitial cell of Cajal, which is normally present in the myenteric plexus. The stomach is the commonest site for GIST within the GI tract, accounting for approximately 60–70% of overall cases. These tumours are characterized by KIT gene mutations that encode transmembrane tyrosine kinase, which in turn is responsible for tumoral growth and survival.29 The identification of KIT (CD117)-activating mutation is usually required for pathological diagnosis and is seen in approximately 95% cases. In a small number of cases, the cells express mutation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α.29,30 The dependence of tumour growth and survival on these cellular markers allows the use of Imatinib (Gleevec®; Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland), which inhibits bcr-abl, KIT, platelet-derived growth factor-α and β tyrosine kinase in these patients.31 The incidence of GIST is almost equal in males and females. Patients with GIST commonly present with non-specific symptoms like abdominal pain and distension.32,33

CT is the imaging investigation of choice for these lesions. On CT, GIST is most commonly seen as an exophytic submucosal mass lesion in the gastric body or antrum but may rarely present as an intraluminal mass or a mixture of both types. Usually tumour is between 3 and 10 cm at the time of diagnosis.33 The smaller lesion can have homogeneous intense enhancement (Figure 7), but with increasing size it is known to undergo necrosis with heterogeneous enhancement (Figure 8). There may be mucosal ulceration in approximately 50% cases of gastric GIST that may be associated with extraluminal oral contrast or air within the mass. Virtual gastroscopy can provide additional information like gastric fold thickening and ulceration (Figure 8c). There are no specific imaging predictors of the behaviour of the tumour; but, various studies have shown that size >5 cm, tumour necrosis, infiltration of the adjacent organ or metastasis, mitotic count >1–5 per 10 high-powered fields and mutation of the cellular KIT (c-KIT) gene are associated with poor patient prognosis.32 Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for these patients, but it is associated with a high rate of recurrence despite tumour-free margins at surgery. Chemotherapy (Imatinib) is the treatment of choice for patients with recurring or metastatic GIST.34 The primary tumour and the secondary deposits typically show decreased enhancement and may become completely cystic after chemotherapy. Sometimes, there may be a paradoxical early increase in the size of the masses and this should not be inferred as disease progression.29,33

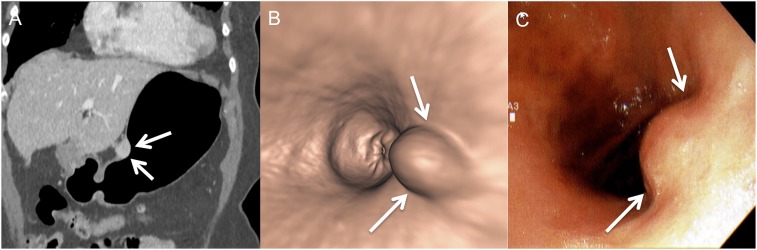

Figure 7.

A 43-year-old female with abdominal pain: the coronal (a) and virtual endoscopy (b) CT images are showing a smooth homogenously enhancing submucosal mass (arrows) along the lesser curvature. There is no fold thickening or ulceration. Conventional endoscopy (c) is showing the mass (arrows) similarly.

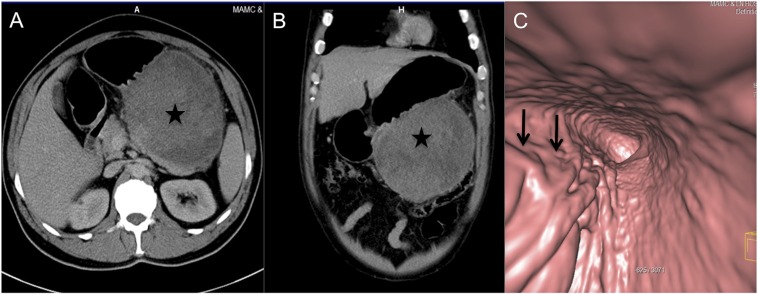

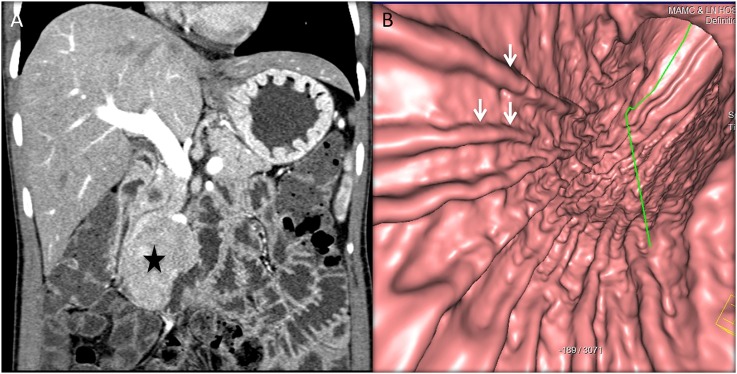

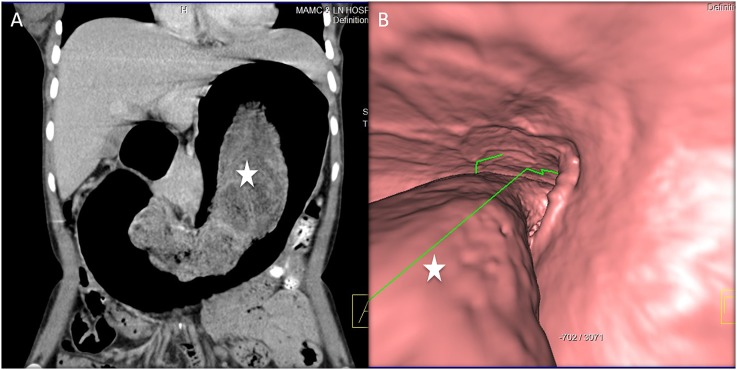

Figure 8.

A 49-year-old male with abdominal distension and early satiety: axial (a) and coronal (b) CT images are showing a large exophytic heterogeneously enhancing mass (stars) arising from the greater curvature of the stomach. The CT gastroscopy image (c) is showing a smooth extrinsic bulge on the stomach owing to the submucosal location with asymmetric fold thickening (arrows) at the greater curvature, biopsy-proven malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumour.

Gastric carcinoid tumour

Gastric carcinoid tumours (GCTs) are rare cancers of the stomach, accounting for approximately 1% of overall neoplasms of the stomach.35 Based on the distinct aetiopathological mechanism, there are three types of GCT. Type 1 GCT, the commonest subtype (approximately 70–80% of GCTs), is associated with autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis and like most autoimmune disorders, it is more common in females. Owing to atrophic gastritis, it is associated with achlorhydria, intrinsic factor deficiency and compensatory hypergastrinemia by excessive activity of gastric G-cells.35 Type 1 GCT is usually benign, seen as single or clustered polyps (Figure 9) and has an excellent prognosis.24,35 Type 2 GCT is the least common subtype and is seen with gastrinomas in association with Zollinger–Ellison syndrome or multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 1. Type 2 GCT can be multicentric and may be associated with multiple masses in the setting of diffuse gastric wall thickening (Figure 10). Lymph node metastasis is also more common with this subtype, but still, tumour-related deaths and carcinoid syndrome are rare.24,35 Type 3 GCT is sporadic and associated with normal gastrin levels.35 Unlike other subtypes, Type 3 GCT is more common in males, usually solitary with ulceration and higher chances of local invasion and distant metastasis.24 Patients with hepatic metastasis may present with carcinoid syndrome. Patients with GCT mostly present with non-specific symptoms clinically. These are commonly detected incidentally on endoscopy, but CT or MRI is usually performed to evaluate the extent of disease. Types 1 and 2 GCT are usually negative on somatostatin receptor scintigraphy with the utility of octreotide scan mostly in detecting metastasis. Also, the present literature does not support the use of FDG-PET for the evaluation of gastric carcinoid.35

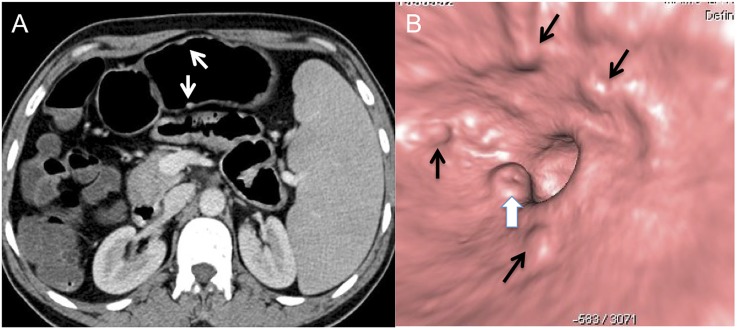

Figure 9.

A 59-year-old female with upper abdominal pain and anaemia: the axial (a) CT image is showing few tiny enhancing lesions (white arrows) arising from the stomach wall and splenomegaly. The CT gastroscopy image (b) is showing multiple small clustered polyps (black arrows) (most were not well seen on conventional CT) with central umbilication on one of the polyps (white block arrow), proven to be an ulcer on conventional endoscopy (not shown).

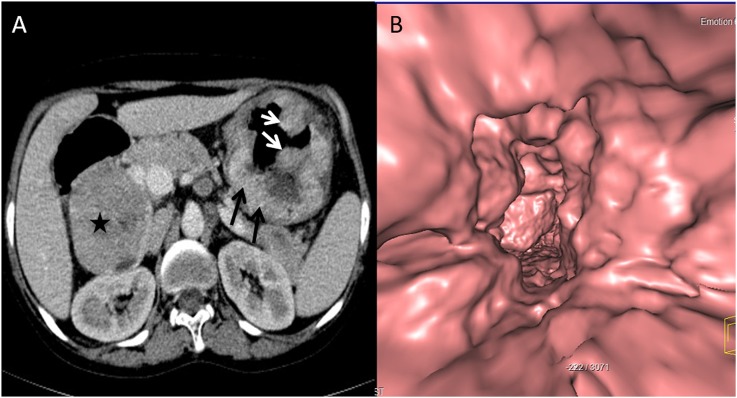

Figure 10.

39-year-old female with a history of prolactinoma presenting with acute abdomen: the axial (a) CT image is showing a large heterogeneous mass in the pancreatic head (star, proven to be gastrinoma) with multiple gastric polyps (white arrows) superimposed on diffuse gastric wall thickening (black arrows). The CT gastroscopy image (b) is showing multiple polyps and diffuse gastric fold thickening. Biopsy of the gastric polyp showed carcinoid tumour and the genetic studies confirmed multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 syndrome.

Gastric metastasis

The metastasis to the stomach is rare and is reported in 0.2–0.7% of overall population in autopsy series, while autopsy series in patients with known primary cancer may show metastasis in up to 5.4%.36–38 Common primary tumours associated with gastric metastasis are lung, breast, melanoma and oesophageal. The gastric metastasis is submucosal, may be single or multiple and is commonly seen in the upper and middle third of the stomach (Figure 11).38 On double-contrast barium examination, the metastasis is classically described as single or multiple “bull's eye” or “target” lesions with a bridging mucosal fold.36 On CT, the presence of single or multiple submucosal lesions in a patient with a known primary malignancy (especially cancers with a higher incidence of gastric metastasis) should raise a suspicion of gastric metastasis and endoscopic biopsy should be performed in these cases for confirmation.24,38

Figure 11.

A 66-year-old male with a history of malignant melanoma of the back, staging CT: the axial (a) and coronal (b) CT images are showing a homogenously enhancing mass along the greater curvature (arrows), proven to be melanoma metastasis on biopsy.

Benign diseases

Gastric lipoma

Gastric lipoma is a rare benign submucosal tumour of the stomach that is composed of the adipose tissue surrounded by a fibrous capsule. It is typically seen at the gastric antrum and is usually detected incidentally.39 If it becomes >3–4 cm, the overlying mucosa may ulcerate and patients may present with acute or chronic upper GI bleed. Since it is usually close to the gastric pylorus, it can also cause outlet obstruction or intussusception.39 The findings that suggest lipoma on double-contrast barium upper GI series include a compressible, well-defined, low-density submucosal mass. CT is very specific for diagnosis and it typically shows a well-defined submucosal mass with an attenuation value around −70 to −120 (Figure 12). There may be mucosal ulceration or linear strands of soft-tissue attenuation at the base. Taylor et al40 suggested that these linear soft-tissue strands should not be mistaken for liposarcoma as it is inherently very rare in the GI tract.

Figure 12.

A 42-year-old male with malignant melanoma, staging CT: the axial CT image is showing an incidental fat attenuation submucosal mass (arrow) in the gastric antrum consistent with a lipoma.

Gastritis

Gastritis is a common benign disease of the stomach that is characterized by the presence of inflammatory cells in the stomach wall. Gastritis can be broadly classified as erosive (related to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, alcohol, stress, systemic illnesses, viral or fungal infection), non-erosive related to Helicobacter pylori infection, atrophic gastritis and hypertrophic gastritis (related to Zollinger–Ellison syndrome and Menetier's disease) and non-infectious (granulomatous and oeosinophilic gastritis).41,42 Endoscopy is most useful for the diagnosis of gastritis and cross-sectional imaging is usually not indicated in patients with gastritis, but these patients are at times imaged because of non-specific clinical features. Thickening of the gastric wall and folds is the most common CT finding in patients with gastritis.41 If the inflammation is severe, there may be layering or “halo” of the gastric wall that is described as hyperenhancing mucosa due to hyperaemia and hypodense submucosa due to oedema from inflammation (Figure 13). This layering is best seen on arterial phase imaging.41 In patients with hypertrophic gastritis and high gastrin levels, CT may provide necessary information about the presence and location of gastrinoma and its relationship with adjacent structures to aid in surgical management (Figure 14). Similarly, a non-specific finding like ascites may be helpful in the diagnosis of the serosal form of eosinophilic gastritis in the appropriate clinical setting.43 There are no studies on the utility of 3D techniques like VE for the evaluation of gastritis, although theoretically it should show gastric fold thickening better than conventional CT. The presence of mural stratification should favour gastritis but in most cases, it is often difficult to distinguish gastric wall and fold thickening owing to gastritis from gastric cancer and endoscopic biopsy is usually needed for definitive diagnosis.

Figure 13.

A 56-year-old male with acute upper abdominal pain: the coronal CT image is showing antral wall thickening, mucosal enhancement (arrows) and submucosal oedema consistent with gastritis.

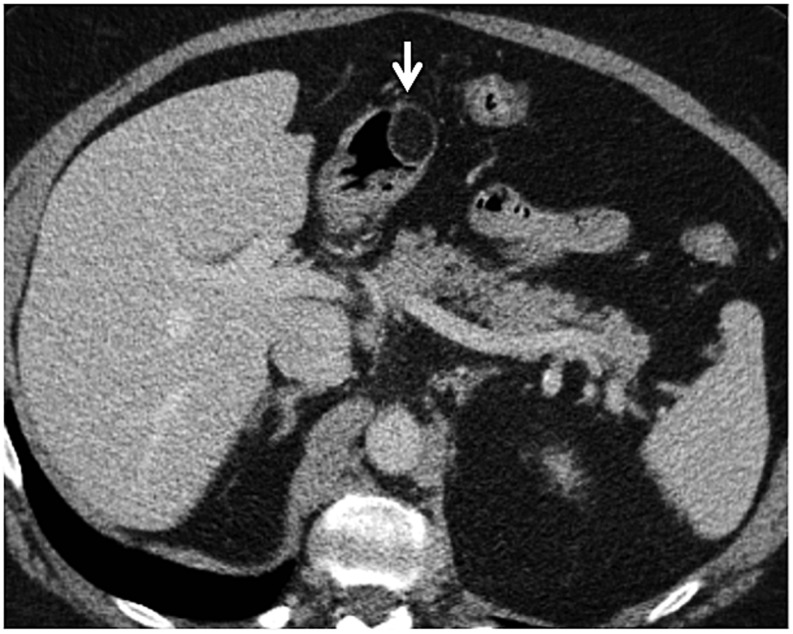

Figure 14.

A 26-year-old female with intractable gastritis and weight loss: the coronal CT image (a) is showing diffuse gastric fold thickening and enhancement. A peripancreatic mass is also visualized (star), proven to be gastrinoma. The virtual gastroscopy image (b) is showing severe diffuse gastric fold thickening (arrows) consistent with hypertrophic gastritis.

Gastric bezoar

A bezoar is defined as an accumulation of ingested foreign material within the stomach. Bezoar is named based on the composition of accumulated material. The common bezoars are phytobezoar (accumulated vegetable matter), trichobezoar (accumulated hair), pharmacobezoar (accumulated medicines) and lactobezoar (accumulated mild curd).44–46 Phytobezoar is the most common gastric bezoar and is typically seen in males between ages of 40 and 50 years, while trichobezoar is typically seen in females in the second decade who usually have psychiatric disorders. The risk factors for the formation of gastric bezoar include gastric dysmotility from prior gastric surgery or vagotomy, gastric outlet obstruction, dehydration, use of opiates (or other gastroparetic medications) and use of medications with insoluble carrying vehicles like enteric-coated aspirin.47 Bezoars are usually detected incidentally in patients undergoing work-up for non-specific symptoms. CT typically shows the presence of an intraluminal mass with typical mottled air lucencies within (Figure 15a). Virtual gastroscopy also shows this mass very well (Figure 15b). It may also be seen on the abdominal radiograph as soft-tissue density with multiple air lucencies or on ultrasound as an epigastric mass with dirty posterior shadowing.48 On double-contrast barium upper GI series, it is seen as an intraluminal filling defect. The management of gastric bezoar depends upon its composition and can be treated by chemical dissolution, endoscopic or surgical removal.

Figure 15.

A 21-year-old female with depression and epigastric fullness: coronal CT (a) and CT gastroscopy (b) images are showing curvilinear mottled intraluminal contents (stars) consistent with a bezoar, surgically proven to be trichobezoar.

Post-operative follow-up

Conventionally, patients got gastric surgery for treatment of gastric or duodenal ulcer refractory to medical management or for resectable malignancy of the stomach. These days, patients undergoing gastric bypass for morbid obesity form the majority of patients undergoing gastric surgery. Surgical resection is still the only definitive management option for gastric cancer. In the patients undergoing surgery for gastric cancer, tumour depth and lymph node involvement are the two most important predictors for recurrent disease.49 “Stump cancer” is defined as a cancer of the gastric remnant that occurs 15–25 years after gastrectomy for gastric ulcer or any other benign aetiology.24 Post-partial or complete gastrectomy, patients are usually followed by CT. CT is a robust tool for the detection of recurring cancer or metastatic spread during follow-up of patients having undergone gastrectomy for gastric cancer (Figure 16). In patients with gastric bypass, CT is usually used to evaluate the anastomosis during follow-up of the patients. “Marginal” ulcer is defined as an ulceration at or adjacent to the suture line, typically seen in patients who have undergone gastrojejunostomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. CT is used to investigate patients with symptoms of obstruction, pain or bleeding after gastric surgery for the detection of complications like stomal stenosis, bleeding or perforation (Figure 17).50 Another popular procedure for bariatric surgery is gastric banding, which involves the application formation of a small gastric pouch by application of an adjustable band, approximately 2 cm below the gastro-oesophageal junction. This gastric band may slip, owing to which the stomach may be more prone to obstruction or volvulus. Normally, the anterior and posterior aspects of the gastric band are superimposed and the angle between the spine and the axis of band should be between 4 and 58°. These features of the gastric band are best assessed on topogram or on coronal images.51 In a preliminary data analysis in patients undergoing laprosopic sleeve gastrectomy, the amount of resected stomach (pre-operative stomach volume minus the volume of the reconstructed sleeve) calculated by MDCT had good correlation with early post-operative weight loss.3

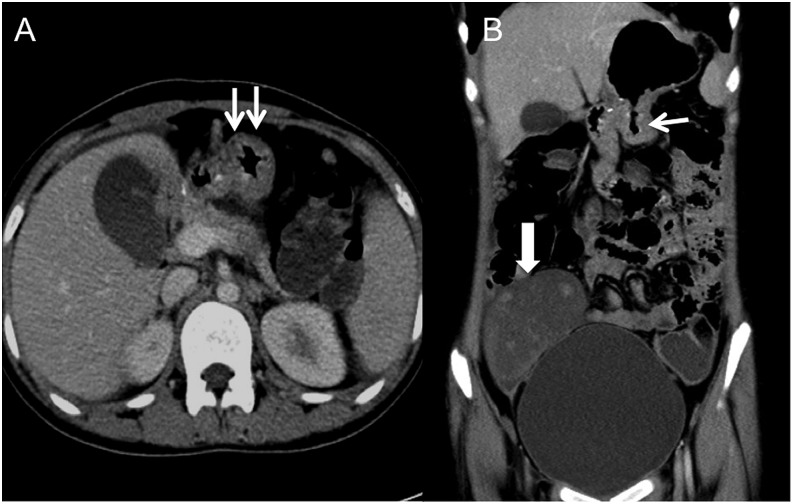

Figure 16.

A 19-year-old female with history of distal gastrectomy for “signet ring”-type gastric cancer, with abdominal pain and loss of appetite: axial (a) and coronal (b) CT images are showing thickening of the stomach (arrows) just proximal to gastrojejunal anastomosis with bilateral Kruckenberg tumours (block arrow). The thickening was proven to be due to recurring disease on histopathology.

Figure 17.

A 44-year-old male with a history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (post-operative Day 18) presenting with abdominal pain: the axial CT (a) image is showing air leak (arrow) at the gastrojejunal anastomosis.

CONCLUSION

CT is the imaging investigation of choice for various gastric pathologies. With the development of newer and better software techniques, the application of CT in these patients continues to grow. Except for gastric cancer, currently there is limited literature on the utility of 3D techniques like VE in imaging of other gastric pathologies. Theoretically, VE should provide better mucosal details in other diseases like gastritis.

It is important to have a dedicated CT protocol for patients with suspected gastric disease, as gastric distension and negative oral contrast have been shown to improve the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. VE also has some disadvantages and limitations that include more time consumption, inability to obtain histopathology and detect pathologies based on the change of mucosal colour, and additional radiation dose. In our experience, these disadvantages outweigh the risk in patients who are carefully selected. With the development of newer CT scanners, radiation dose should be substantially reduced, which partially overcomes the disadvantage of increased radiation dose; but, further prospective studies are required to establish the validity of this technique. Further studies in patients undergoing bariatric surgery (particularly sleeve gastrectomy) may also expand the utility of CT in predicting post-surgical weight loss and appropriate patient prognostication.

Contributor Information

Prashant Nagpal, Email: drnishantnagpal@gmail.com, prashant-nagpal@uiowa.edu.

Anjali Prakash, Email: anjali_prakash@hotmail.com.

Gaurav Pradhan, Email: gspradhan@gmail.com.

Aditi Vidholia, Email: aditi-vidholia@uiowa.edu.

Nishant Nagpal, Email: drnishantnagpal@gmail.com.

Sachin S Saboo, Email: Sachin.Saboo@utsouthwestern.edu.

David M Kuehn, Email: david-m-kuehn@uiowa.edu.

Ashish Khandelwal, Email: AKHANDELWAL1@partners.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim JH, Park SH, Hong HS, Auh YH. CT gastrography. Abdom Imaging 2005; 30: 509–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-004-0282-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim AY, Kim HJ, Ha HK. Gastric cancer by multidetector row CT: preoperative staging. Abdom Imaging 2005; 30: 465–72. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-004-0273-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawanindra L, Vindal A, Midha M, Nagpal P, Manchanda A, Chander J. Early post-operative weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy correlates with the volume of the excised stomach and not with that of the sleeve! Preliminary data from a multi-detector computed tomography-based study. Surg Endosc 2015; 29: 2921–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-4021-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hori S, Tsuda K, Murayama S, Matsushita M, Yukawa K, Kozuka T. CT of gastric carcinoma: preliminary results with a new scanning technique. Radiographics 1992; 12: 257–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.12.2.1561415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhandari S, Shim CS, Kim JH, Jung IS, Cho JY, Lee JS, et al. Usefulness of three-dimensional, multidetector row CT (virtual gastroscopy and multiplanar reconstruction) in the evaluation of gastric cancer: a comparison with conventional endoscopy, EUS, and histopathology. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59: 619–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5107(04)00169-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HS, Han HY, Choi JA, Park CM, Cha IH, Chung KB, et al. Preoperative evaluation of gastric cancer: value of spiral CT during gastric arteriography (CTGA). Abdom Imaging 2001; 26: 123–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s002610000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghimire P, Wu GY, Zhu L. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17: 697–707. doi: https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i6.697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, Mackey JR, Joy AA, Hamilton SM. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg 2005; 241: 27–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Virmani V, Khandelwal A, Sethi V, Fraser-Hill M, Fasih N, Kielar A. Neoplastic stomach lesions and their mimickers: spectrum of imaging manifestations. Cancer Imaging 2012; 12: 269–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1102/1470-7330.2012.0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 69–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen Y, Kang HK, Jeong YY. Evaluation of early gastric cancer at multidetector CT with multiplanar reformation and virtual endoscopy. Radiographics 2011; 31: 189–99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.311105502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hundahl SA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base Report on poor survival of U.S. gastric carcinoma patients treated with gastrectomy: fifth edition American Joint Committee on cancer staging, proximal disease, and the “different disease” hypothesis. Cancer 2000; 88: 921–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000215)88:4<921::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17: 3077–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-1362-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zurleni T, Gjoni E, Ballabio A, Casieri R, Ceriani P. Sixth and seventh tumor-node-metastasis staging system compared in gastric cancer patients. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 5: 287–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v5.i11.287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Habermann CR, Weiss F, Riecken R. Preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma: comparison of helical CT and endoscopic US. Radiology 2004; 230: 465–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2302020828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gossios K, Tsianos E, Prassopoulos P, Papakonstantinou O, Tsimoyiannis E, Gourtsoyiannis N. Usefulness of the non-distension of the stomach in the evaluation of perigastric invasion in advanced gastric cancer by CT. Eur J Radiol 1998; 29: 61–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0720-048X(98)00024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimizu K, Ito K, Matsunaga N, Shimizu A, Kawakami Y. Diagnosis of gastric cancer with MDCT using the water-filling method and multiplanar reconstruction: CT-histologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185: 1152–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.04.0651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Kim AY, Oh ST, Kim JS, Kim KW. Gastric cancer staging at multi-detector row CT gastrography: comparison of transverse and volumetric CT scanning. Radiology 2005; 236: 879–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2363041101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei WZ, Yu JP, Li J, Liu CS, Zheng XH. Evaluation of contrast-enhanced helical hydro-CT in staging gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11: 4592–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i29.4592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dux M, Richter GM, Hansmann J, Kuntz C, Kauffmann GW. Helical hydro-CT for diagnosis and staging of gastric carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1999; 23: 913–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CY, Kuo YT, Lee CH. Differentiation between malignant and benign gastric ulcers: CT virtual gastroscopy versus optical gastroendoscopy. Radiology 2009; 252: 410–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2522081249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang SW, Lee DH, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, et al. Preoperative staging of gastric cancer by endoscopic ultrasonography and multidetector-row computed tomography. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 25: 512–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06106.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JH, Eun HW, Hong SS, Auh YH. Early gastric cancer: virtual gastroscopy. Abdom Imaging 2006; 31: 507–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-005-0183-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ba-Ssalamah A, Prokop M, Uffmann M, Pokieser P, Teleky B, Lechner G. Dedicated multidetector CT of the stomach: spectrum of diseases. Radiographics 2003; 23: 625–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.233025127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cogliatti SB, Schmid U, Schumacher U. Primary B-cell gastric lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 145 patients. Gastroenterology 1991; 101: 1159–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(91)90063-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fishman EK, Urban BA, Hruban RH. CT of the stomach: spectrum of disease. Radiographics 1996; 16: 1035–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.16.5.8888389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamadol N, Wongwiwatchai J, Wachirakowit T, Pairojkul C. Computed tomographic features of adenocarcinoma compared to malignant lymphoma of the stomach. J Med Assoc Thai 2011; 94: 1387–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radan L, Fischer D, Bar-Shalom R, Dann EJ, Epelbaum R, Haim N, et al. FDG avidity and PET/CT patterns in primary gastric lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008; 35: 1424–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-008-0771-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong X, Choi H, Loyer EM, Benjamin RS, Trent JC, Charnsangavej C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: role of CT in diagnosis and in response evaluation and surveillance after treatment with imatinib. Radiographics 2006; 26: 481–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.262055097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, McGreevey L, Chen CJ, Joseph N, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 2003; 299: 708–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1079666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joensuu H, Roberts PJ, Sarlomo-Rikala M. Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1052–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200104053441404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pidhorecky I, Cheney RT, Kraybill WG, Gibbs JF. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: current diagnosis, biologic behavior, and management. Ann Surg Oncol 2000; 7: 705–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10434-000-0705-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandrasegaran K, Rajesh A, Rydberg J, Rushing DA, Akisik FM, Henley JD. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 184: 803–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.184.3.01840803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blackstein ME, Blay JY, Corless C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment. Can J Gastroenterol 2006; 20: 157–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2006/434761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikou GC, Angelopoulos TP. Current concepts on gastric carcinoid tumors. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012; 2012: 287825. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/287825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green LK. Hematogenous metastases to the stomach. A review of 67 cases. Cancer 1990; 65: 1596–600. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(19900401)65:7<1596::AID-CNCR2820650724>3.0.CO;2-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campoli PM, Ejima FH, Cardoso DM, Silva OQ, Santana Filho JB, Queiroz Barreto PA, et al. Metastatic cancer to the stomach. Gastric Cancer 2006; 9: 19–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-005-0352-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kondo H, Yamao T, Saito D, Ono H, Gotoda T, Yamaguchi H, et al. Metastatic tumors to the stomach: analysis of 54 patients diagnosed at endoscopy and 347 autopsy cases. Endoscopy 2001; 33: 507–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-14960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson WM, Kende AI, Levy AD. Imaging characteristics of gastric lipomas in 16 adult and pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 181: 981–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.181.4.1810981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor AJ, Stewart ET, Dodds WJ. Gastrointestinal lipomas: a radiologic and pathologic review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990; 155: 1205–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.155.6.2122666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horton KM, Fishman EK. Current role of CT in imaging of the stomach. Radiographics 2003; 23: 75–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.231025071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney system. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol 1996; 20: 1161–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta P, Singla R, Kumar S, Singh N, Nagpal P, Kar P. Eosinophilic ascites. A rare presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J Assoc Physicians India 2012; 60: 53–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J. Bezoars and foreign bodies of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 1996; 6: 605–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ripolles T, Garcia-Aguayo J, Martinez MJ, Gil P. Gastrointestinal bezoars: sonographic and CT characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 177: 65–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.177.1.1770065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DuBose TM, 5th, Southgate WM, Hill JG. Lactobezoars: a patient series and literature review. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2001; 40: 603–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stack PE, Thomas E. Pharmacobezoar: an evolving new entity. Dig Dis 1995; 13: 356–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000171515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Newman B, Girdany BR. Gastric trichobezoars—sonographic and computed tomographic appearance. Pediatr Radiol 1990; 20: 526–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02011382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marrelli D, De Stefano A, de Manzoni G, Morgagni P, Di Leo A, Roviello F. Prediction of recurrence after radical surgery for gastric cancer: a scoring system obtained from a prospective multicenter study. Ann Surg 2005; 241: 247–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000152019.14741.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guniganti P, Bradenham CH, Raptis C, Menias CO, Mellnick VM. CT of gastric emergencies. Radiographics 2015; 35: 1909–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2015150062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sonavane SK, Menias CO, Kantawala KP, Shanbhogue AK, Prasad SR, Eagon JC, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: what radiologists need to know. Radiographics 2012; 32: 1161–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.324115177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]