Abstract

Objective:

To identify cerebral regions preserved by successful recanalization of the middle cerebral artery M1 segment and their association with early clinical outcome.

Methods:

47 patients who underwent endovascular treatment for acute unilateral M1 segment occlusion were included. Successful recanalization was defined by a modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction score of 2b/3. Final infarct volumes were segmented on follow-up MRI/CT, 2–7 days post-symptom onset. The differences in topography of infarct lesions associated with successful vs unsuccessful recanalization were assessed using voxel-based analysis. Favourable outcome was defined by a modified Rankin Scale score ≤2 at discharge, and disability/death by score >2.

Results:

Successful recanalization of M1 segment occlusion was achieved in 26/47 (55%) patients, which was associated with higher rate of favourable outcome (54% vs 9%, p = 0.002) and smaller final infarct volumes (34.3 ± 43.7 vs 98.1 ± 47.7 ml, p < 0.001). In voxel-based analysis, patients with successful recanalization had a lower rate of infarction in precentral gyrus and posterior insular ribbon compared with those without recanalization. Favourable outcome was achieved in 16 (34%) patients, who were younger (62.2 ± 13.9 vs 70.9 ± 13.9, p = 0.048), had higher rate of successful recanalization (88% vs 39%, p = 0.002) and had smaller infarct volumes (25.2 ± 23.6 vs 82.2 ± 57.1 ml, p < 0.001) compared with those with disability/death. In voxel-based analysis, infarction of the insula, precentral gyrus, middle centrum semiovale and corona radiata were associated with disability/death.

Conclusion:

Successful endovascular recanalization of acute M1 segment occlusion tends to preserve posterior insular ribbon and precentral gyrus from infarction; and infarction of these regions was associated with higher rates of disability/death.

Advances in knowledge:

The knowledge of the topographic location of potentially salvageable cerebral tissue can provide additional information for treatment triage and selection of patients with acute stroke for endovascular treatment based on the “areas at risk” rather than the “volume at risk”. Also, such knowledge can help with preferential recanalization, where the neurointerventionalist may choose to preferentially recanalize certain branches supplying salvageable and eloquent cerebral regions in favour of timely reperfusion treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple recent clinical trials have shown lower rates of disability/death following endovascular treatment in patients with acute anterior circulation ischaemic stroke compared with standard treatment including i.v. recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA).1 The trials were successful largely because of the use of third-generation thrombectomy devices and the application of advanced imaging for patient selection.2–4 The imaging was used to identify treatable arterial occlusions and to select patients who were most likely to have a favourable clinical outcome through direct or indirect identification of small ischaemic cores.2–4

Prior studies have shown that early recanalization of middle cerebral artery (MCA) prevents infarct growth, results in smaller final infarct size, and improves the clinical outcome.5 The final infarct volume size and extent are also related to the initial infarct volume, recanalization status, CT angiography (CTA) collateral score and admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score.6,7 However, it is not yet well established whether improved outcomes following arterial revascularization are solely explained by the reduction in final infarct size or, at least in part, by preservation of specific eloquent brain regions.8 Localization of those cerebral areas within the MCA territory, where occurrence of infarction is linked to persistent disability, is critical, since such regions are potentially the best targets for preservation by early arterial recanalization.8,9 One can argue that the perfusion status of such areas may be more important for therapeutic decisions and prognostication than the infarct volume.10

While the infarct volume size has been widely evaluated in stroke neuroimaging studies, there are scarce reports on the associations of the infarct location with stroke outcome and treatment response. In the present study, we used a voxel-based analysis method for identification of cerebral regions, which are associated with early disability/death; and those regions are potentially preserved by successful MCA recanalization.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of consecutive ischaemic stroke admitted to two university-affiliated hospitals from December 2006 to June 2010.11,12 All patients who (1) had unilateral M1 segment occlusion, (2) underwent endovascular treatment and (3) had follow-up MRI or CT scan from 48 h to 7 days after symptom onset were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they had (1) simultaneous occlusion of internal cerebral artery (ICA) or anterior cerebral artery; (2) developed post-procedural intraparenchymal haematoma on follow-up CT/MRI scans; or (3) had a prior or follow-up stroke within 3 months of the endovascular treatment. The following items were extracted from stroke database for the analysis:: age, gender, admission NIHSS score, time interval between symptom onset and microcatheter placement (onset-to-catheterization time), hemispheric side and the type of endovascular treatments received. Favourable functional outcome was defined by a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score ≤2 at the time of discharge, whereas disability/death was defined by a mRS score >2. The methodology for data collection was approved by the local institutional review board.

Treatment and angiographic recanalization assessment

The treatment protocol for patients with ischaemic stroke included in this study has been described previously.11,12 All patients who were eligible for receiving i.v. rt-PA, as per then-current treatment guideline, received i.v. rt-PA.13,14 Those patients who had received i.v. rt-PA but presented with severe clinical symptoms (NIHSS score of ≥10) and large arterial occlusion underwent additional endovascular treatment. In addition, those patients who presented within 8 h of symptom onset, but did not fulfil the criteria for i.v. rt-PA treatment, received endovascular treatment based on quantitative and qualitative analyses of admission CT perfusion scan. For endovascular treatment, patients received intra-arterial thrombolytic and/or underwent thrombectomy.11,12 The recanalization success was assessed using the modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (mTICI) scoring system.15 Successful recanalization was defined by achieving mTICI 2b (perfusion with >50% distal branch filling) or mTICI 3 (perfusion with filling in all distal branches).15

Voxel-based image analysis

The subacute ischaemic infarct lesions were manually segmented on MRI fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery or CT images (if MRI was not available) with helps from intensity filtering. In patients with multiple post-procedural scans, the MRI/CT scans with an acquisition time closest to 48 h after symptom onset were chosen. The binary infarct lesion masks were affine registered to the standard MNI-152 space using the FLIRT tool included in the FSL software (Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK).16,17 Separate infarct lesion summation maps were created for patients with and without successful recanalization. Each voxel in summation maps represented the total number of patients with infarct involving that particular voxel coordinate (Figure 1). The non-parametric mapping tool included in the MRIcron software package (McCausland Center for Brain Imaging, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC) was used for the voxel-based lesion symptom analysis.18,19 Given the limited number of patients, all left hemispheric infarct lesions were flipped onto the right hemisphere. For dichotomized outcome variables, a binary group, binary image comparison was performed for each voxel (infarcted vs non-infarcted) using the successful recanalization or disability/death as the dependent variables. For ordinal outcome variables, a continuous group, binary image comparison was performed for each voxel with post-catheterization mTICI score or discharge mRS score as the dependent variables. The final mTICI scores were transformed into ordinal variables from 0 to 4. In all voxel-based lesion symptom analyses, only voxels with lesion in ≥10 cases were included. Using the Brunner–Munzel Rank order test, Z score maps were developed for each series of analysis, in which higher score values indicate more frequent infarct occurrence associated with the outcome variable in each particular voxel. For all analysis, Bonferroni familywise error correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons, with 2000 permutations to compensate for the small sample size. The colour-coded map of Z scores are overlaid on the MNI-152 standard brain space for depiction purposes (Figures 2 and 3). Narrowed windows are applied in all maps to depict Z score ranges corresponding to approximately 0.05–0.01 p-value thresholds.

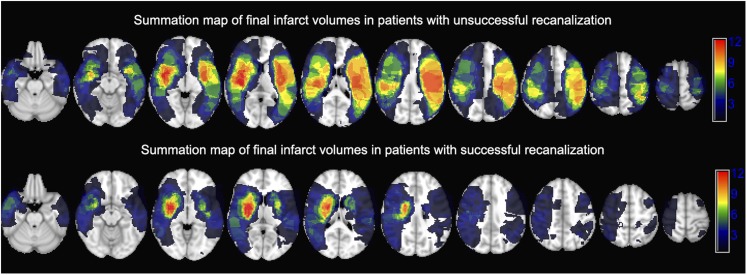

Figure 1.

A summation map of the final infarct volumes in patients with (n = 26) vs without (n = 21) successful recanalization of the occluded M1 segment overlaid on MNI-152 brain space: each voxel value represents the total number of patients with ischaemic infarct of that particular coordinate on follow-up MRI/CT scan.

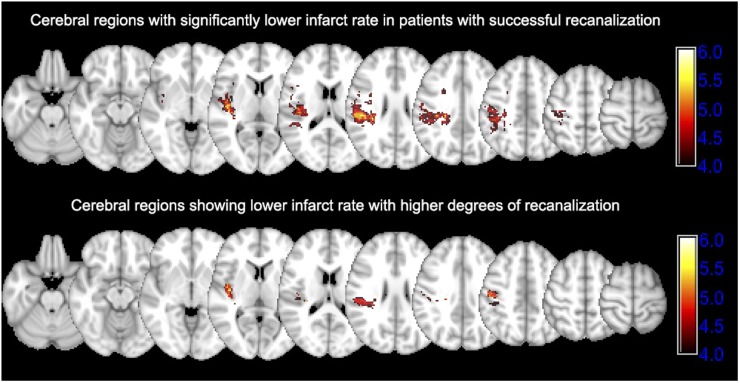

Figure 2.

Cerebral regions saved by successful recanalization of occluded M1 segment: the upper row shows the Z score map of voxel-based analysis comparing infarct lesion distribution between patients with successful vs unsuccessful recanalization. Higher Z score values show regions with lower rate of infarction in patients with successful recanalization (n = 26) compared with those without (n = 21). Bonferroni familywise error (FWE)-corrected p-value→Z score equivalents: 0.050→4.368, 0.025→4.523 and 0.01→4.937. The lower row shows the Z score map associating infarct lesion distribution with the recanalization degree based on the modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction (mTICI) scoring system. Higher Z score values show regions with lower rate of infarction associated with higher mTICI scores. Bonferroni FWE-corrected p-value→Z score equivalents: 0.050→4.555, 0.025→4.699 and 0.01→4.882.

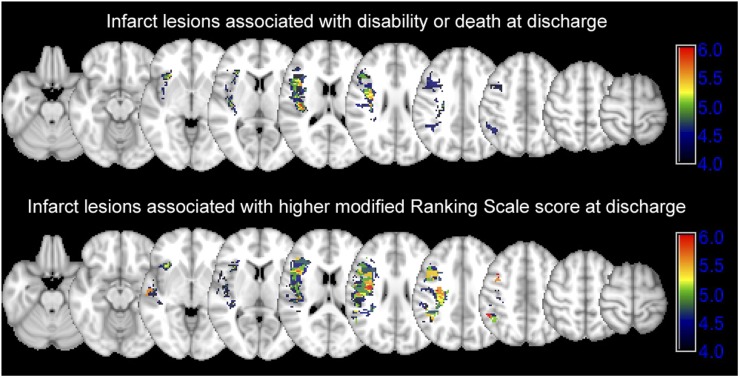

Figure 3.

Infarct lesions associated with poor clinical outcome: the upper row shows the Z score map of voxel-based analysis comparing infarct lesion distribution between patients with disability/death at the time of discharge. Bonferroni familywise error (FWE) corrected p-value→Z score equivalents: 0.050→4.367, 0.025→4.529 and 0.01→4.721. The lower row shows the Z score map associating infarct lesion distribution with the higher discharge modified Rankin scale score (higher Z score values). Bonferroni FWE-corrected p-value→Z score equivalents: 0.050→4.488, 0.025→4.633 and 0.01→4.820.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or number (frequency), wherever appropriate. Continuous variables were compared with the Student's t-test, categorical variables with the χ2 test and ordinal variables with the Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS® Statistics for Mac v. 23.0 (IBM Corp., New York, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The mean age of 47 patients included in this study was 67.9 ± 14.4 years; and 27 (57%) were males. The median NIHSS score at presentation was 20 (interquartile: 15–23). The average onset-to-catheterization time was 4.9 ± 2.5 h; and 25 (53%) had left M1 segment occlusion. Regarding the treatment, 25 (53%) received i.v. rt-PA, 37 (79%) received intra-arterial rt-PA, 31 (66%) had mechanical thrombectomy and 18 (38%) underwent angioplasty. Follow-up MRI scans were available in 36 patients; and the subacute infarct lesions were segmented on follow-up CT scan in remaining 11 patients.

Recanalization success

Following endovascular treatment, successful recanalization (mTICI 2b/3) was achieved in 26 (55%) patients. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of patients dichotomized based on the recanalization success. Patients with successful recanalization had smaller final infarct volume, lower discharge mRS scores and lower rates of disability/death (Table 1). Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of final infarct lesions on follow-up scan of patients categorized based on recanalization success. Overall, there was higher frequency of infarction in lentiform nucleus and central corona radiata regardless of recanalization status. Figure 2 compares the distribution of infarct lesions between patients with successful vs unsuccessful recanalization and based on the degree of recanalization. The rate of infarct occurrence was significantly lower in precentral gyrus and posterior insular ribbon of patients who had successful recanalization compared with those without recanalization (Figure 2). Similarly, worse recanalization status (ordinal variable) as identified by lower mTICI scores was associated with infarction of precentral gyrus and posterior insula (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics according to recanalization successa

| Patients with successful recanalization (n = 26) | Patients without successful recanalization (n = 21) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.0 ± 14.1 | 66.7 ± 14.9 | 0.579 |

| Male gender | 16 (62%) | 11 (52%) | 0.566 |

| Admission NIHSS score | 19.5 (15–23) | 20 (13–23) | 0.949 |

| Onset-to-catheterization time (h) | 4.4 ± 2.0 | 5.5 ± 2.9 | 0.171 |

| Left M1 segment occlusion | 14 (54%) | 11 (52%) | 1.000 |

| i.v. rt-PA | 15 (58%) | 10 (48%) | 0.564 |

| IA thrombolytic treatment | 21 (81%) | 16 (76%) | 0.734 |

| Mechanical thrombectomyb | 17 (65%) | 14 (67%) | 1.000 |

| Discharge mRS score | 2 (0–4) | 4 (5–6) | <0.001*** |

| Favourable outcome at dischargec | 14 (54%) | 2 (9%) | 0.002** |

| Subacute infarct lesion volume (ml) | 34.3 ± 43.7 | 98.1 ± 47.7 | <0.001*** |

IA, intra-arterial; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; rt-PA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Successful recanalization was defined by achieving modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction 2b/3.15

One patient could have received both IA thrombolytic treatment and mechanical thrombectomy.

Favourable outcome at discharge defined by an mRS score ≤2.

p value < 0.01.

p value < 0.001.

Clinical outcome

Favourable outcome was achieved in 16 (34%) patients. Patients with favourable outcome were younger, had higher rate of successful M1 segment recanalization and has smaller final infarct volumes compared with those with disability/death (Table 2). The voxel-based analysis showed that infarct lesions in the insula, precentral gyrus, middle centrum semiovale and corona radiata are associated with higher rates of disability/death and discharge mRS scores (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics according to clinical outcome at dischargea

| Patients with disability/deatha (n = 31) | Patients with favourable outcomea (n = 16) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.9 ± 13.9 | 62.2 ± 13.9 | 0.048* |

| Male gender | 17 (55%) | 10 (63%) | 0.758 |

| Admission NIHSS score | 20 (18–24) | 17 (15–22) | 0.147 |

| Onset-to-catheterization time (h) | 4.9 ± 2.8 | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 0.858 |

| Left M1 occlusion | 17 (55%) | 8 (50%) | 0.768 |

| i.v. rt-PA | 18 (58%) | 7 (44%) | 0.376 |

| IA thrombolytic treatment | 23 (74%) | 14 (88%) | 0.457 |

| Mechanical thrombectomyb | 20 (65%) | 11 (69%) | 1.000 |

| Successful recanalizationc | 12 (39%) | 14 (88%) | 0.002** |

| Subacute infarct lesion volume (ml) | 82.2 ± 57.1 | 25.2 ± 23.6 | <0.001*** |

IA, intra-arterial; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; rt-PA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator.

Favourable outcome at discharge defined by an mRS score ≤2, and disability/death by an mRS score >2.

One patient could have received both IA thrombolytic treatment and mechanical thrombectomy.

Successful recanalization was defined by achieving modified thrombolysis in cerebral infarction 2b/3.15

p value < 0.05.

p value < 0.01.

p value < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have confirmed the association of successful recanalization of occluded M1 segment with smaller final infarction volume and lower rate of disability/death. Using a voxel-based analysis with no priori, we have also shown that successful M1 recanalization is associated with lower rates of ischaemic infarct along the central sulcus and posterior insular ribbon. In addition, infarctions of insular ribbon, precentral gyrus, middle centrum semiovale and corona radiata were associated with higher rates of disability/death at discharge. These findings support a shift of emphasis from “how-much-saved” to “what-was-saved” concept. The topography of potentially salvageable cerebral tissue may also provide additional information to assist in treatment triage and patient selection. For example, if precentral gyrus and posterior insular ribbon are already infarcted based on pre-procedural imaging, the endovascular procedure may be of limited value.

Also, currently, the target for endovascular treatment is recanalization without the option of preferential recanalization. Preferential recanalization would mean that occlusion of certain branches that supply critical areas of the brain would be treated first. The most practical application of our knowledge from topographic distribution of salvageable cerebral regions and eloquent areas is probably that the neurointerventionalist may choose not to aggressively seek recanalization of certain branches that supply non-critical areas in situations, where risks of administering additional thrombolytic or using thrombectomy devices may be higher than average risk owing to the time that has elapsed since symptom onset or the morphology of occluded artery.

Since the present study included procedures performed prior to the approval of the stent retrievers thrombectomy devices, the rates of angiographic recanalization might have been higher if stent retrievers had been used, as evident from the results of two randomized clinical trials that have compared the rates of angiographic recanalization between stent retrievers and prior thrombectomy devices.20,21 However, the higher rates of angiographic recanalization are unlikely to affect the topology of salvaged cerebral tissue.

Our results are similar to Rosso et al8 showing that recanalization of ICA/MCA is associated with lower apparent diffusion coefficient values in lenticular nucleus, internal capsule and periventricular white matter. In their series, the infarction of aforementioned regions was associated with higher 3-month mRS scores. Notably, Rosso et al8 included patients who had occlusion at different segments of MCA with or without ICA thrombosis. Also, patients in their cohort had variably received different types of thrombolytic treatments, while the arterial recanalization was assessed based on follow-up MRA. In our series, we restricted our study to patients with M1 segment occlusion who received endovascular treatment, and recanalization was assessed based on the immediate angiographic assessment. These patients appear to represent the target group benefiting from stroke endovascular intervention, and restriction of analysis to those with M1 segment occlusion prevents heterogeneity introduced by variable anatomy of M2 branching among patients. Our results showed an association between precentral gyrus and posterior insular infarct with failure to recanalize the occluded M1 segment.

The results of recent clinical trials suggest a secondary goal for stroke imaging to identify proximal arterial or large vessel occlusion and to assess the extent of ischaemic core or areas at risk of infarction.22 A growing body of evidence suggest that localization of the infarct core or penumbra can also help predict outcome as much as or even better than the volume of the hypoperfused tissue.10 Both initial infarct lesion volume and location on diffusion-weighted imaging are predictors of disability/death in patients with stroke following endovascular therapy.23 Patients with basal ganglia infarction or deep white matter lesions on diffusion-weighted imaging had worse clinical outcome after endovascular therapy.9,23 In addition, the insular ribbon infarction was associated with higher likelihood of growth into the hypoperfused penumbra and increased rate of poor outcome despite smaller initial infarct volume.24,25 A voxel-based analysis of consecutive patients with stroke also showed that infarction of corona radiata, internal capsule and insula was associated with higher mRS scores at 1-month follow-up.26

The selective vulnerability of central MCA territory, striatum and adjacent white matter is attributed to the sole blood supply from lateral lenticulostriate arterial branches of MCA without any other collateral supply.27 It is likely that the vascular supply to the insula reflects the confluence of bulk flow through the MCA divisions, clot location and collateral flow.28,29 Moreover, topographic studies have shown that the insula has higher vulnerability for infarction following hypoperfusion (i.e. reduced blood flow).16 Also, patients with stroke and reduced blood flow in insular ribbon are less likely to recover from aphasia or paralysis.30,31 Our results also show the association of insular infarction with poor clinical outcome, while successful endovascular intervention was able to preserve the insula from infarction [specially the posterior banks of insula (Figure 2)]. Our findings can also potentially help with interpretation and clinical application of perfusion imaging. For example, an aggressive endovascular intervention for rescue of a hypoperfused but still viable insular cortex can be considered in patients with acute M1 segment occlusion, given that it has high likelihood of being preserved by successful recanalization. However, it should be noted that the preservation of eloquent areas of the brain is not the only reason for endovascular intervention in patients with stroke with M1 occlusion, but also prevention of infarct growth with associated complications.

Our work has limitations inherent to its design as a retrospective observational study with small sample size. The patients were preselected based on initial CT perfusion studies or clinical severity and thus may not be representative of all patients with MCA occlusion. It should also be noted that in addition to the recanalization status, the initial infarct volume, CTA collateral score and admission NIHSS score might affect the final infarct volume.6,7 Moreover, long-term outcome results, like 3-month mRS scores, were not available in all patients. Also, the reliable measures of initial infarct core and/or penumbra volumes were not available in all cases for analysis. In addition, the infarct location recanalization analysis represents a univariate methodology with topographic distribution of final infarct being evaluated as a consequence of successful vs unsuccessful recanalization of M1, which may be oversimplified. Moreover, although a Bonferroni familywise error correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons, a multivariable general linear model may be able to incorporate other clinical and imaging variables in voxel-based analysis. Finally, our analysis only shows the association between the infarct location and successful vs unsuccessful recanalization and cannot confirm a true cause–effect relationship.

CONCLUSION

Using a voxel-based analysis, the precentral gyrus and posterior insular ribbon were identified as cerebral regions, which appear to be preserved following successful recanalization of occluded M1 segment. These regions overlap with those areas where infarction is associated with higher rates of disability/death at discharge—i.e. insular ribbon, middle centrum semiovale, corona radiata and precentral gyrus. Future studies are warranted to confirm present results and establish the clinical applications of these findings. The knowledge of potentially salvageable cerebral regions can provide additional information for treatment triage and selection of patients with acute stroke for endovascular treatment based on “area at risk” rather than “volume at risk” as well as preferential recanalization.

Contributor Information

Seyedmehdi Payabvash, Email: spayab@gmail.com.

Shayandokht Taleb, Email: staleb@umn.edu.

Adnan I Qureshi, Email: qureshai@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qureshi AI, Ishfaq MF, Rahman HA, Thomas AP. Endovascular treatment versus best medical treatment in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016; 37: 1068–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, van den Berg LA, Lingsma HF, Yoo AJ, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 11–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1411587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J, et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1019–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1414905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, Yassi N, et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1009–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1414792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rha JH, Saver JL. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: a meta-analysis. Stroke 2007; 38: 967–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000258112.14918.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elijovich L, Goyal N, Mainali S, Hoit D, Arthur AS, Whitehead M, et al. CTA collateral score predicts infarct volume and clinical outcome after endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke: a retrospective chart review. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 559–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krongold M, Almekhlafi MA, Demchuk AM, Coutts SB, Frayne R, Eilaghi A. Final infarct volume estimation on 1-week follow-up MR imaging is feasible and is dependent on recanalization status. Neuroimage Clin 2015; 7: 1–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosso C, Colliot O, Valabregue R, Crozier S, Dormont D, Lehericy S, et al. Tissue at risk in the deep middle cerebral artery territory is critical to stroke outcome. Neuroradiology 2011; 53: 763–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-011-0916-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seitz RJ, Sondermann V, Wittsack HJ, Siebler M. Lesion patterns in successful and failed thrombolysis in middle cerebral artery stroke. Neuroradiology 2009; 51: 865–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-009-0576-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosso C, Samson Y. The ischemic penumbra: the location rather than the volume of recovery determines outcome. Curr Opin Neurol 2014; 27: 35–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000000047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payabvash S, Qureshi MH, Khan SM, Khan M, Majidi S, Pawar S, et al. Differentiating intraparenchymal hemorrhage from contrast extravasation on post-procedural noncontrast CT scan in acute ischemic stroke patients undergoing endovascular treatment. Neuroradiology 2014; 56: 737–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-014-1381-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payabvash S, Qureshi MH, Taleb S, Pawar S, Qureshi AI. Middle cerebral artery residual contrast stagnation on noncontrast CT scan following endovascular treatment in acute ischemic stroke patients. J Neuroimaging 2015; 25: 946–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jon.12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tekle WG, Chaudhry SA, Fatima Z, Ahmed M, Khalil S, Hassan AE, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in expanded time window (3–4.5 hours) in general practice with concurrent availability of endovascular treatment. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2012; 5: 22–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asaithambi G, Hassan AE, Chaudhry SA, Rodriguez GJ, Suri MF, Taylor RA, et al. Comparison of time to treatment between intravenous and endovascular thrombolytic treatments for acute ischemic stroke. J Vasc Interv Neurol 2011; 4: 15–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoo AJ, Simonsen CZ, Prabhakaran S, Chaudhry ZA, Issa MA, Fugate JE, et al. Refining angiographic biomarkers of revascularization: improving outcome prediction after intra-arterial therapy. Stroke 2013; 44: 2509–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payabvash S, Souza LC, Wang Y, Schaefer PW, Furie KL, Halpern EF, et al. Regional ischemic vulnerability of the brain to hypoperfusion: the need for location specific computed tomography perfusion thresholds in acute stroke patients. Stroke 2011; 42: 1255–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Payabvash S, Taleb S, Benson JC, McKinney AM. Interhemispheric asymmetry in distribution of infarct lesions among acute ischemic stroke patients presenting to hospital. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2016; 25: 2464–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rorden C, Karnath HO, Bonilha L. Improving lesion-symptom mapping. J Cogn Neurosci 2007; 19: 1081–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.7.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payabvash S, Taleb S, Benson JC, McKinney AM. Acute ischemic stroke infarct topology: association with lesion volume and severity of symptoms at admission and discharge. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017; 38: 58–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nogueira RG, Lutsep HL, Gupta R, Jovin TG, Albers GW, Walker GA, et al. Trevo versus Merci retrievers for thrombectomy revascularisation of large vessel occlusions in acute ischaemic stroke (TREVO 2): a randomised trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1231–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61299-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saver JL, Jahan R, Levy EI, Jovin TG, Baxter B, Nogueira RG, et al. Solitaire flow restoration device versus the Merci Retriever in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (SWIFT): a randomised, parallel-group, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 1241–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61384-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malhotra K, Liebeskind DS. Imaging in endovascular stroke trials. J Neuroimaging 2015; 25: 517–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jon.12272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tateishi Y, Wisco D, Aoki J, George P, Katzan I, Toth G, et al. Large deep white matter lesions may predict futile recanalization in endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Interv Neurol 2015; 3: 48–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1159/000369835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamalian S, Kemmling A, Borgie RC, Morais LT, Payabvash S, Franceschi AM, et al. Admission insular infarction >25% is the strongest predictor of large mismatch loss in proximal middle cerebral artery stroke. Stroke 2013; 44: 3084–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timpone VM, Lev MH, Kamalian S, Morais LT, Franceschi AM, Souza L, et al. Percentage insula ribbon infarction of >50% identifies patients likely to have poor clinical outcome despite small DWI infarct volume. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 40–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng B, Forkert ND, Zavaglia M, Hilgetag CC, Golsari A, Siemonsen S, et al. Influence of stroke infarct location on functional outcome measured by the modified rankin scale. Stroke 2014; 45: 1695–702. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedrich B, Gawlitza M, Schob S, Hobohm C, Raviolo M, Hoffmann KT, et al. Distance to thrombus in acute middle cerebral artery occlusion: a predictor of outcome after intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015; 46: 692–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ay H, Arsava EM, Koroshetz WJ, Sorensen AG. Middle cerebral artery infarcts encompassing the insula are more prone to growth. Stroke 2008; 39: 373–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.499095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fink JN, Selim MH, Kumar S, Voetsch B, Fong WC, Caplan LR. Insular cortex infarction in acute middle cerebral artery territory stroke: predictor of stroke severity and vascular lesion. Arch Neurol 2005; 62: 1081–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.62.7.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payabvash S, Kamalian S, Fung S, Wang Y, Passanese J, Kamalian S, et al. Predicting language improvement in acute stroke patients presenting with aphasia: a multivariate logistic model using location-weighted atlas-based analysis of admission CT perfusion scans. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31: 1661–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Payabvash S, Souza LC, Kamalian S, Wang Y, Passanese J, Kamalian S, et al. Location-weighted CTP analysis predicts early motor improvement in stroke: a preliminary study. Neurology 2012; 78: 1853–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]