Abstract

Objective:

Towards Safer Radiotherapy recommended that radiotherapy (RT) centres should have protocols in place for in vivo dosimetry (IVD) monitoring at the beginning of patient treatment courses (Donaldson S. Towards safer radiotherapy. R Coll Radiol 2008). This report determines IVD implementation in the UK in 2014, the methods used and makes recommendations on future use.

Methods:

Evidence from peer-reviewed journals was used in conjunction with the first survey of UK RT centre IVD practice since the publication of Towards Safer Radiotherapy. In March 2014, profession-specific questionnaires were sent to radiographer, clinical oncologist and physics staff groups in each of the 66 UK RT centres.

Results:

Response rates from each group were 74%, 45% and 74%, respectively. 73% of RT centres indicated that they performed IVD. Diodes are the most popular IVD device. Thermoluminescent dosimeter (TLD) is still in use in a number of centres but not as a sole modality, being used in conjunction with diodes and/or electronic portal imaging device (EPID). The use of EPID dosimetry is increasing and is considered of most potential value for both geometric and dosimetric verification.

Conclusion:

Owing to technological advances, such as electronic data transfer, independent monitor unit checking and daily image-guided radiotherapy, the overall risk of adverse treatment events in RT has been substantially reduced. However, the use of IVD may prevent a serious radiation incident. Point dose IVD is not considered suited to the requirements of verifying advanced RT techniques, leaving EPID dosimetry as the current modality likely to be developed as a future standard.

Advances in knowledge:

An updated perspective on UK IVD use and provision of professional guidelines for future implementation.

INTRODUCTION

In 2008, a joint report entitled “Implementing in vivo dosimetry”2 was published by the British Institute of Radiology, the Royal College of Radiologists, the Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine and the Society and College of Radiographers. This report promoted a risk assessed and staged approach to implementing in vivo dosimetry (IVD) in the UK and was in response to the recommendations made by the “Towards Safer Radiotherapy” report (TSRT)1 and the “Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer” in 2006.3

The report recognized that implementing a programme of IVD into a service would need resource, concluding that individual centres should decide which patient groups receive IVD and make this decision on the basis of risk and available resource.

In 2014, the Radiotherapy Board, comprising representatives from the Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine, Royal College of Radiologists and Society and College of Radiographers, requested a review and update of the 2008 report. This move was supported by Public Health England. The purpose of this review is to assess the status of IVD in the UK, provide information on available technology, consider the use of IVD in context with other safeguards and make evidence-based recommendations on the future use of IVD. The work presented herein was produced with oversight from the Radiotherapy Board.

Radiotherapy (RT) is an essential modality in the treatment of cancer, with approximately 50% of patients with cancer treated by RT at some stage. Cancer Research UK have reported that approximately 40% of all patients cured of cancer have RT as part of their treatment; that 16% of patients are cured by RT alone; and that RT is second only to surgery as a cure for cancer.4 RT is also a highly complex process requiring input from different staff groups, and the consequences of error for patients can be significant.2

Following a serious radiation incident in 2006, the Chief Medical Officer report of 20063 contained a section on IVD recommending that measuring the dose received by each patient should become routine in RT in the UK. In 2008, the multiprofessional document Towards Safer Radiotherapy1 recommended that all centres should have protocols for IVD monitoring for most patients at the beginning of treatment.

These publications generated considerable discussion within the UK RT physics community, with arguments presented that the widespread implementation of IVD with diodes was not cost effective and that diverting resources from within a RT service to commission and implement IVD could lead to errors elsewhere.6,7 It has further been argued8 that some of the causes of RT errors have been eliminated with developments such as the use of electronic data transfer between the treatment planning systems (TPS) and treatment units removing the risk of manual transcription error. With the introduction of (IVD) measures into the Manual for Cancer Services9 came confirmation that national compliance with IVD requirements was expected. Some of the difficulties surrounding IVD were acknowledged in “Implementing in vivo dosimetry”.2 However, given the rapid increase in RT treatment complexity since the publication of “Implementing in vivo dosimetry”, it is appropriate to conduct a reappraisal.

A survey of UK IVD practice in 200410 showed little change in practice over the 10 years preceding it. However, the impact of the Chief Medical Officer 2006 recommendation, that IVD should be routine, has not been assessed.3 This recommendation was intended to provide new impetus for the use of IVD in the UK. What remains unclear is the extent to which (a) this recommendation has influenced the uptake of IVD; (b) what types of IVD are being used and in what context; and (c) how relevant is current IVD practice in the context of evolving technology and clinical practice.

There is a gap in knowledge of UK IVD practice with no survey of UK IVD practice having been conducted since the Chief Medical Officer 2006 recommendation. To address this knowledge gap, the authors conducted a UK-wide IVD survey and a literature review, which are presented in this article.

While the Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer in 2006 recommends risk assessed routine implementation of IVD, its use must be viewed in the context of other technological advances such as electronic data transfer and image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT), which contribute to patient safety. It can be argued that the risk of an error caused by human factors is diminishing as electronic data transfer and improved imaging capabilities are becoming standard. Focus should therefore turn to the rapid advances in technology including dose verification.

It is important to consider IVD as part of a portfolio of safety measures, the choice of each being made as a result of rigorous risk assessment of the treatment processes and techniques. Limited resource means that guidance is required evaluating not just the technologies available, but also their appropriate use. It is essential for patients and the public to have absolute confidence in safety measures and the question of whether to implement IVD needs to be viewed together with other safety measures.

To provide this view, and to provide broad recommendations on future use of IVD using a risk analysis model, the authors present a snapshot of IVD use in the UK; discuss existing practice in the context of the evidence base for using IVD; and provide analysis of possible IVD solutions for RT. We provide analysis of IVD solutions for RT addressing their benefits and limitations. We do not report on specific vendors. The authors hope that service providers will find this article helpful when considering IVD solutions for their RT service.

REVIEW OF IN VIVO DOSIMETRY TECHNOLOGY

Technology background

In 2013, the International Atomic Energy Authority published recommendations on IVD implementation11 using thermoluminescent detectors (TLDs), silicon diodes, metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors and optically stimulated luminescence detectors. As well as detailing relevant commissioning procedures, the document describes the underlying physics of these technologies. Of the detectors evaluated, only TLDs and silicon diodes appear to be in widespread use in the UK. The basic process for both devices is to calibrate under known conditions “ex vivo”; the detectors can then be placed on the skin of patients undergoing RT to measure the dose actually delivered. The resultant measurement is compared with the predicted result to check whether it agrees with the intended dose. Until recently, the term “in vivo dosimetry” has been synonymous with either silicon diodes or TLDs, and generally the term has been applied to measurement within the beam rather than beyond the field edge.

In this report, we also include electronic portal imaging devices (EPIDs), inherent in nearly all modern linear accelerators, as these are widely considered the best contender for the future of (IVD). They detect radiation after it has passed through the patient, so many useful measurements can be made.

Transmission detectors

There has been a recent growth of interest in the use of transmission detectors—flat-panel ion chambers or diode arrays attached to the head of a linear accelerator, upstream of the patient. Their purpose is to monitor the radiation fluence produced by the treatment unit. Interlocks may be present to terminate the exposure if preset tolerances are exceeded. There is some division of opinion as to the utility of these devices, as they do not strictly measure the dose received by the patient and take no account of the correctness of patient position relative to the linear accelerator. They may provide unwanted attenuation across the beam, together with increase in surface dose and scattered dose to the patient. However, transmission detectors have been designed for use as daily dose verification and offer dose measurement over the whole two-dimensional (2D) treatment delivery area. Transmission detectors would provide a higher level of assurance as to the correct delivery of individual treatments than a single-point dose measurement with a diode, with correctness of patient position determined by pre-treatment cone-beam CT (CBCT). As the 2014 survey predates the arrival of this technology, and on which there is little published clinical work to reference, it is not discussed further in this report.

Thermoluminescent dosemeters

For many years, TLDs were the only option for any practical in vivo dose measurement. TLDs have been available in both solid and powdered forms, with TLD-100 (LiF: Mg, Ti) being the most commonly used material. However, a major drawback associated with these dosemeters is the requirement for post-irradiation processing by heating the sample and measuring the light output from it to determine the dose received. This means “real-time” dose measurement is impossible and is a major reason why TLDs began to be replaced by diodes when they first started to be used in RT in the mid-1980s. While TLDs are still in use in some applications, e.g. Total Body Irradiation (TBI) dosimetry and postal dosimetry audits, they only provide point dose information (as do diodes), and their use is not generally considered commensurate with the modern requirements of highly conformal adaptive and IGRT.

Diodes

Silicon diodes have been available for use in RT for over 25 years.12 The principles of diode dosimetry appear simple but are in practice, quite complex. Accurate diode dosimetry requires the use of numerous correction factors to correct for changes between calibration and treatment conditions, including source-to-skin distance (SSD), field size, energy, the presence of wedge modifier, temperature of the diode, oblique incidence and missing tissue. Implementing and maintaining an IVD service within a clinical department carries a significant overhead in terms of staff time and access to linear accelerators. With all correction factors applied, most users would agree that a tolerance between calculated and measured doses of 5% is acceptable in most cases. A less rigorous application of correction factors would require more generous tolerances of up to 10% to minimize the number of false-positive readings obtained,11 at which point the system may be at risk of missing a reportable error.

There have been a number of studies citing the error detection rate of diode dosimetry. Between 1995 and 2000, the following authors reported error rates: Noel et al13 reported a 1.05% error detection rate in measurement on 7519 patients; Fioriono et al5 reported 9 serious errors out of 2824 measurements on 1433 patients, with a rate of 0.63%; and Calandrino et al14 noted 3 (0.5%) serious errors out of 650 patients.

In 1994, 17 out of 59 centres were performing central axis IVD.15 In a repeat of that survey in 2004, Edwards et al10 reported that over the intervening decade, this number rose modestly to 22 centres. It should be noted that a larger number of centres were performing measurements close to the edge of beams for critical structure measurements in the 2008 survey.

Diodes were originally developed for use within radiation beams and they could easily be placed on the central axis of a photon beam by treating radiographers. Within the past 15 years, diodes have also become available for use in electron beams and “edge of field” monitoring for critical structures.10 Several studies have demonstrated that both photon and electron diodes can produce significant attenuation of the beams in which they are placed, resulting in underdose of tissues (tumour) lying at depth. This feature of diode dosimetry has restricted the number of fractions in which a diode may be used in any given treatment course.16

A further significant development in UK RT practice was the imperative to develop intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). Given the finite size of diode detectors, concerns were raised about the efficacy of using diodes in highly modulated beams and the meaning of the results obtained. Alaei et al17 cite diode agreement to within 10% of the planned dose on 76% of 300 treatment beams. Vinall et al18 cite the use of diodes as a complementary check to EPID dosimetry in a study involving 80 patients and 437 IMRT fields. Measured diode doses were within 5% of those expected for 95% of IMRT fields, representing excellent agreement, but the technique required considerable preparation which may not be considered sustainable in many departments.

There is little reference in the literature to the use of diodes in volumetric-modulated arc therapy (VMAT) beams. However, the logic of using a diode detector to measure dose at a single point in a dynamically rotating delivery is contentious, highlighting the need for a risk assessed approach to clinical implementation of IVD, given the paucity of evidence for its effectiveness in that context. If no viable IVD solution is available, pre-treatment patient-specific verification can ensure the deliverability of an individual plan, with daily online imaging ensuring the geometric delivery accuracy. The implementation of VMAT in the UK has been rapid and to date, it has been used more in radical treatments.

With the development of EPID-based dosimetry and the more widespread use of VMAT-type delivery, the clinical use of diodes in photon beams is likely to decline. However, diodes are likely to remain the mainstay of simple palliative care treatments.

Electronic portal imaging device

In a review of IVD by Mijnheer et al,19 the rationale for IVD is argued with the conclusion that it should be used for all treatments with curative intent in combination with pre-treatment checks. Given the questions discussed elsewhere in this report over the efficacy of diodes, particularly in the context of new and emerging techniques, this section presents a brief overview of the current state of EPID IVD systems. Table 1 highlights the main advantages and disadvantages of the devices discussed in this report.

Table 1.

Main in vivo dosimetry devices used in the UK, pros and cons (adapted from Mijnheer et al19)

| TLD | Diode | EPID | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main use | Entrance point dose | Entrance point dose | Exit 2D dose plane and 2D/3D dose reconstructions |

| Main error checks | SSD Output of linear accelerator Dose modifiers, e.g. wedges |

SSD Output of linear accelerator Dose modifiers, e.g. wedges |

Output of linear accelerator Dose modulation in 2D Anatomical changes |

| Main advantages | No cables, reusable after annealing, few corrections | Good reproducibility, immediate readout | 2D and 3D dose distributions, immediate read out, permanent record |

| Main disadvantages | Labour intensive, specific equipment for readout, delay in obtaining results | Cumbersome calibration, many corrections, cables easily damaged and expensive to replace | Cost of software, limited availability of commercial software, increased physics time investigating out of tolerance results |

2D, two dimensional; 3D, three dimensional; EPID, electronic portal imaging device; SSD, source-to-skin distance; TLD, thermoluminescent dosimeter.

EPID panels are installed on all modern linear accelerators; hence, the hardware is widely available to carry out EPID-based IVD. However, the hardware alone is not sufficient to implement it. Software is required to analyze the results of EPID measurements and produce predicted results to allow comparison. The investment in getting EPID dosimetry into clinical use for IVD cannot be neglected in terms of either developing or purchasing software to facilitate IVD using the EPID output. Either route will require substantial commissioning. Once commissioned, there will be a significant increase in physics time required to investigate out of tolerance EPID results, by the simple reason of more data being measured and issues being detected that were never seen with diodes, including the inevitable false-positive results.

The commercial solutions currently available are just emerging, but were not mature enough for widespread adoption when the survey was conducted. There is a commercial product based on the work described in the study by Pinkerton et al;20 however, it was only for pre-treatment verification (without the patient present), not for IVD. Another commercial system is based on the GLAaS algorithm, as described in Nicolini et al.21 Clinical results from the commercial systems have been presented at conferences recently, and studies are starting to be published. Narayanasamy et al22 report on both phantom verification and patient-specific IVD using Dosimetry Check (Math Resolutions, Columbia, MD). Results are based on 23 IMRT plans from different sites, where both gamma analysis and dose–volume histogram changes are evaluated. EPID IVD for point dose verification is implemented in the EPIgray software (DOSIsoft, France), based on the algorithm explained by Boissard et al.23 Clinical results on 30–60 patients are reported in the 2 publications by Ricketts et al.24,25 Ricketts et al report on identifying errors due to anatomy changes based on this point-based EPID system.

However, the vast majority of published clinical results are from non-commercial software developed in-house, such as the system implemented at the NKI in Amsterdam and described in detail by Wendling et al.26 The clinical results from the NKI are promising and the latest studies by Olaciregui-Ruiz et al27 and Mijnheer et al28 highlight how the clinical IVD process can be automated: “The EPID dosimetry has been fully automated and integrated in our clinical workflow where currently about 3000 IMRT/VMAT and about 2500 non-IMRT treatments are verified each year”. 95% of these measurements are automatically analyzed without manual intervention; for the remaining 5%, errors in acquisition of the EPID images or dosimetric errors were flagged. By automation, the work load of EPID IVD can be managed and resources can be concentrated on the problematic results.

A commercial version of the NKI software called iViewDose has been produced. This product does EPID dosimetry for individual treatments within the vendor-specific RT management framework. Manual analysis is required, but with appropriate setup it is comparable with time spent on thermoluminescent dosimeter (TLD) readout. While representing progress, this solution requires significant investment of physics time and resource, is limited to one vendor and comes at a cost per linear accelerator and per treatment energy.

In addition to the NKI system, Maastro Clinic, Maastricht, Netherlands has implemented an EPID dosimetry system, first on their Siemens linear accelerators and more recently on their Varian linear accelerators. This system has recently been installed at the Christie in Manchester and was reported on at ESTRO Electronic Portal Imaging conference, 2014.26 Both of these systems can be used both in 2D on a field-by-field basis for conformal and IMRT treatments and in three dimensional (3D) for verification of all treatment types, including VMAT. In addition, the systems have the possibility of automation. However, fully automatic analysis of EPID dose results is currently not available commercially.

In vivo dosimetry survey 2014

Overview

Three surveys were conducted, in the summer of 2014, to gather information about the current position and department practices with regard to using IVD in the UK RT pathway. Surveys were sent to every UK RT centre specifically aimed at each of the professional groups. In the UK, there are 61 NHS providers across 64 sites and 5 independent/private providers across 11 sites; i.e. 66 providers, all of which were requested to submit 1 response to each of the surveys. The response rate for the survey is given in Table 2. The responses from the radiographer and physics surveys, although close in number, do not all come from the same treatment centres. Therefore, some discrepancy in answers is to be expected.

Table 2.

Survey response

| Staff surveyed | Number of survey questions | Number of centres sent a survey | Number of responders | Response rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiographers | 18 | 66 | 49 | 74% |

| Clinical oncologists | 7 | 64 | 29 | 45% |

| Physicists | 25 | 65 | 48 | 74% |

Design and analysis of survey questions

The aim was to gain a broad view across the three professions regarding the use of IVD, keeping the number of questions and detail required at a reasonable level. In a number of respects, the questions differed in each survey reflecting the different work practices of each profession. All surveys had a combination of yes/no answers and free-text responses to allow explanations of local experience and practice. The free-text replies were grouped into some main themes. It can be noted that centres answering the questions on one survey may not have chosen to answer similar questions on another.

Survey summary

The survey (detailed in the Appendix A) presents a picture of diverse practice across the UK with some providers having decided not to implement IVD and many others questioning the validity of diodes after the advent of electronic data transfer. 73% of providers reported using routine IVD, with 27% providers not routinely using IVD. A small percentage declared no intention of implementing it. The reasons for this are varied but reflect the debate about the value of traditional IVD as a quality control tool within the portfolio of patient safety measures.

It is significant that 73% of providers use IVD. Edwards et al10 reported in 2008 that routine central axis IVD was conducted by 37% (22/59) of providers, while 73% (43/59) providers conducted critical organ dosimetry only. The 2008 figures represented little progress from 1994. That this survey shows significant increase in routine IVD is evidence that intervention from the chief medical officer has provided impetus to its implementation as a patient safety measure.

Historically, IVD has largely been based on the use of diodes, and the continuation of this practice is reflected in the survey results. Diodes were designed when RT mainly consisted of conformal treatments using three or four static beams. In the environment of treatment data being communicated via manual transcription from paper setup sheets and limited treatment imaging capabilities, they made sense as a final check of treatment delivery. However, this survey comes at a time when RT centres are rapidly switching over to IMRT, VMAT and highly modulated conformal treatments, and all have electronic data transfer between their TPS and linear accelerators. This, combined with the advent of linear accelerator-based kilovoltage imaging systems allowing daily online IGRT of patient setup, removes a lot of the reasons for the use of diodes.

The survey results indicate a very low level of error detection using diode-based IVD. When considered in the context of the widespread use of diodes as the primary method of IVD, this fuels the debate about the value of current practice.

The survey shows a positive move towards the emerging field of EPID-based transit dosimetry. Responses showed a trend for centres not currently carrying out IVD and centres with experience of diode-based IVD planning to move their service over to EPID dosimetry. There is also a clear clinical interest in a reliable and efficient IVD system to aid in identifying errors, while corrective action can be applied. However, there is disagreement on whether such a system can be implemented currently.

Full details of the surveys can be found in the Appendix A.

DISCUSSION

IVD is an additional check on the final delivery of treatment relative to the planned dose. It is another step in a process that already contains a variety of safety and quality control measures such as electronic data transfer, independent data checking, independent electronic monitor unit (MU) checking, pre-treatment verification measurements and verification imaging. IVD will not identify the cause of the error detected but has the potential to flag an error, due to either output or incorrect use of compensation or wedges, all of which should be independently checked as routine in any department. This IVD investigation process requires staff resource to be assigned. Exit dosimetry has the potential to, in addition, detect errors that may be due to patient shape or anatomy changes, and these changes can also be identified by the use of IGRT which should be standard in all departments. The errors and changes highlighted by this process add a large workload to the planning and treatment work streams. The extra man-hours required and the high-level skills necessary for this analysis should be acknowledged when introducing this service.

Given the increasing complexity of RT treatments and the qualities of IVD detection methods described elsewhere in this report, it is appropriate to ask questions about the future role and direction of IVD. The rapid pace of technological development in RT demands clarity on the role of IVD as a means of providing quality assurance (QA) with advanced techniques.

The 2008 joint report on implementing IVD2 recommended that this be carried out taking into account the degree of risk and resource required. Data gathered from the UK-wide IVD survey conducted for this report indicate that 13 departments have not implemented IVD using diodes, presumably because they determine risk to be manageable and costs to outweigh benefit. This theme emerges in the literature,6,7,29 where some opinions within the RT professional community argue IVD with diodes is not cost effective and may divert limited resources from elsewhere adversely impacting on risk.

This should not be interpreted as opposition to the use of IVD. Survey data indicate that of those choosing not to implement diode IVD, most have a preference for and are moving towards emerging systems of dose assurance (EPID dosimetry) over traditional methods. There is no international consensus available, but author contacts in the USA, Australia and Canada report similar views.

The future

The literature reviewed within Section 2.3 of this document and the survey results detailed in Appendix A show significant levels of false-positive results occur owing to the complexity of making IVD measurements with diodes. Reducing these to manageable levels requires an increase in measurement tolerances and the development of robust local procedures.11 The costs associated with establishing and operating IVD using diodes, the impact of technical constraints on error detection rates and the level of false results have significant resource implications. Coupled with the increasing complexity of RT treatments, it is reasonable to question whether diodes remain fit for purpose.

The conclusion of Mijnheer et al19 supporting IVD in combination with pre-treatment checks is an argument in support of the status quo. The original guidance advocating risk assessed methods of ensuring that the correct dose is delivered is still relevant. The landscape has, however, changed as a result of technological developments.

An appraisal of the efficacy of diode technology casts doubt upon its suitability for QA in advanced RT. There are grounds to question the efficacy of diodes, and on this basis we recommend a move away from using diodes as a method of IVD for advanced RT. Change should be subject to risk assessment with providers ensuring that QA on planning systems, linear accelerators and connectivity are sufficiently robust to ensure safe delivery of planned RT treatment.

When reviewing local patient safety systems, it should be noted that IVD is a QA tool. It does not eliminate risk of error, and indeed there are errors it will not detect. It should not therefore be seen as guarantor of safety. Rather, providers should assess risk and develop services accordingly. Where IVD is to be used, we recommend resource be directed towards commercially available EPID systems and emerging technology supporting the development and implementation of advanced RT treatments.

Point dose measurements for IVD are really meaningful or representative of the RT treatment only as long as the treatment is of uniform dose from each beam, i.e. conventional or conformal RT. If, however, IVD could give a representative result of the dose delivered in vivo for advanced RT, (which by now account for significantly >25% of all curative RT treatments in UK), then a 2D or 3D dose distribution is required to give an assessment of treatment accuracy. Looking to the future, the Radiotherapy Board publication—“Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy (IMRT) in the UK: Current access and predictions of future access rates”,30 suggests that IMRT/VMAT should account for 50% of all radical treatments in the next 3–5 years and “virtually all radical cases and for many palliative cases within the next 10 years”. This does mean that, based on current evidence, EPIDs provide the best prospect of an IVD system for VMAT, with transmission devices a possible option if they can prove equal or superior utility to EPIDs. It also means that manufacturers should be encouraged to support the development of EPID dosimetry to ensure the availability of IVD for complex delivery techniques.

CONCLUSION

The issue of IVD in RT has been discussed and researched for decades and over this period, RT treatments have changed substantially. We suggest an analysis of the need for IVD is required, in each RT department. This should be generated by reviewing the work practices and technology in place for each treatment modality pathway. Previous evidence may not be applicable to new ways of working.

The implementation of IVD is technology dependent, and it is therefore difficult to establish a framework for commissioning. The authors considered this approach, determining that the diversity of technology and service models in RT would make writing such a framework challenging. We concluded this was not a practical approach and that locally based risk assessed implementation should be recommended. This is consistent with the original recommendation from the 2008 joint report.2

For simple treatments such as palliative applied fields, parallel-opposed fields or electron treatments where either manual calculations or manual data entry are used, a simple IVD solution may be a valid methodology. Depending on the level of independent electronic MU checking available and robustness of process, simple IVD may be advisable. However, simple IVD solutions are not appropriate for use in assuring the dose delivered using advanced RT techniques. This requires development of solutions tailored to measuring dose delivered across highly modulated beams.

Improvements in data transfer and IGRT are positive developments that contribute to greater treatment accuracy. They do not, however, provide assurance of dose delivered. Pre-treatment measurement of VMAT and IMRT plans provides assurance that the machine delivery is correct before the patient enters the treatment room, provided the pre-treatment QA is run with the actual plan that will be used to treat the patient and that no further changes are made to the plan after verification.

There is potential to deliver full adaptive RT with one technology utilizing EPID-based dosimetry, together with CBCT, to provide the information required to plan and deliver an adaptive treatment regime safely and efficiently. This also acts as an effective IVD solution for simpler treatments with a high degree of accuracy and better specificity than diode technology. Although, at present, there is no commercial EPID dosimetry solution based on CBCT.

Whether treatment is delivered with simple or complex RT techniques, there is a patient safety imperative to ensure the dose delivered is that which was planned. In this, IVD has a role to play.

RECOMMENDATIONS

RT providers should implement local protocols for verifying therapeutic radiation dose is delivered as prescribed. These should be risk assessed and take account of locally available staffing and financial resource.

RT providers can use diode-based point dose verification for simple applied single-field (photon or electron), parallel-opposed field treatments and standard conformal treatments.

Diode-based point dose measurements are not appropriate for verification of dose delivered when treating with highly modulated, rotational or adaptive techniques.

RT providers should implement alternative methods of dose verification when implementing highly modulated, rotational or adaptive treatment techniques. These should include QA of planning systems, electronic MU checking, linear accelerators and electronic connectivity with daily online IGRT as standard.

RT providers should invest in the development and clinical implementation of EPID-based IVD solutions to provide end point assurance of dose delivery when treating with highly modulated, rotational or adaptive RT techniques. The emerging technology of transmission detectors may be considered if they can be proven to provide equivalent (or superior) utility to EPID systems.

RT providers should develop a strategy supporting the development of commercially available EPID systems and emerging technologies to deliver end point assurance of dose delivery.

The future implementation of EPID-based IVD should be facilitated through the sharing of expertise within RT centres across the UK. Previously used models of peer support should be utilized to support centres and control costs.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors and board would like to thank the following people for their help in preparing the report: Radiotherapy Board members—Una Findlay (Senior Clinical Radiotherapy Officer, Public Health England), Prof Roger Taylor (Professor of Clinical Oncology, Singleton Hospital, Swansea) and Derek D'Souza (Head of Radiotherapy Physics, UCLH, London); and Clinical Radiotherapy and Professional Society—Mike Pearson (Barts Health NHS Trust); Narinder Lalli (UCLH, London), Angela Baker (Clatterbridge Cancer Centre, Liverpool), Ursula Johnson (UCLH, London), John Rodgers (Christie, Manchester), Sarah Helyer (The Royal Marsden, London), Sarah James (Society of Radiographers) and Alice Futers (IPEM).

Appendix A

RESPONSES TO SURVEY QUESTIONS

Surveys were conducted in the summer of 2014 and sent to every UK RT centre addressed to each of the three professional groups. The chapter headings denote the general aim of questions, with tables per section detailing the staff group questioned, questions asked and optional answers (if any). The free-text answers have been used in various sections to provide additional information where appropriate.

A1. DO YOU PERFORM IVD?

Table A1.

Questions on what IVD each department does

| Staff group | Question | Optional answers |

|---|---|---|

| Physics and radiographers | If routinely perform IVD and which method they used | TLD |

| Diode | ||

| EPID point dose | ||

| EPID planar dose | ||

| EPID 3 dose | ||

| Other (free text) | ||

| Physics and radiographers | Centres that did not perform routine IVD were asked why | No time to implement |

| No commercial systems available to do what is required | ||

| IVD is not considered required | ||

| Lack of capital and revenue funds (physicists only) | ||

| Other (free text) | ||

| Physics and radiographers | Centres that did not perform routine IVD were asked whether they planned to implement IVD and which method did they plan to use | Diode |

| EPID point dose | ||

| EPID planar dose | ||

| EPID 3 dose | ||

| Other (free text) |

TLD, thermoluminescent dosimeter.

The question “do you use IVD” was asked in physics and radiographer surveys, both of which had a 74% response rate. There was good agreement in the responses received, showing that 27% of departments do not routinely carry out IVD.

Of the 73% of providers using IVD, the question was asked “which method you currently use”? The majority of centres carrying out routine IVD use diodes (85%), with the remaining 15% using EPIDs. Free-text responses from physics respondents show a trend for centres using diodes moving to EPID for VMAT and IMRT. Where possible, the physics responses are classified by the local IVD technique(s).

The 13 responders not currently using IVD in each survey were asked their future intentions. Four centres in the physics survey and three centres in the radiographer survey have no plans to use IVD in the future. The remaining 10 responses show a preference for the development and implementation of emerging IVD systems over traditional methods.

Where no IVD is used or planned, the centres were asked the reasons. A total of two centres responded to the radiographer survey, and three centres responded to the physics survey with all options selected at least once. Free-text comments from the physics survey included:

IVDs not amenable to tomotherapy units

pre-treatment QA checks should eliminate errors

sensitivity of systems do not detect errors in field size, shape and SSD <3 cm

internal audit demonstrated no evidence of improved patient safety.

A2. WHICH PATIENT GROUPS HAVE ROUTINE IVD?

Table A2.

Patient groups having IVD

| Staff group | Question | Optional answers |

|---|---|---|

| Physics and radiographers | Which patient groups have routine IVD | In Figure A3 |

| Clinicians | Which patient groups have routine IVD | In Figure A4 |

| Clinicians | Is IVD appropriate for nearly all patients | Free text |

| Clinicians | Which group of staff were involved in selecting patients for IVD | Clinicians |

| Physicists | ||

| Radiographers | ||

| Radiographers | Whether departments had written protocols and work instructions for IVD | |

| Physics | How long they and been doing IVD routinely | Less than 1 year |

| 1–5 years | ||

| More than 5 years | ||

| Radiographers | When they undertook IVD | First fraction only |

| First and second fraction only | ||

| First–third fractions | ||

| Other (free text) |

All three surveys asked which patient groups IVD is used for. In total, 36 centres responded in the physics survey, 34 centres responded in the radiographer survey and 29 centres responded in the clinical oncologist survey. There is a broad agreement between the physics and radiographer responses (Figure A3); however, the clinical oncologists were given slightly different categories (Figure A4). Several of the responses were categorized based on the local IVD methodology implemented. As no centre was using TLD for a full routine IVD service, only for specialized treatment techniques or out of field dose measurements, they were not included in this categorization. In cases where multiple systems were used, these were formed into a separate group. The clinicians were asked which group is responsible for selecting patients for IVD, and most responses indicated a multidisciplinary approach across the three staff groups with 83% centres involving physicists and 72% centres involving clinicians and radiographers.

Figure A3.

IVD by patient group (physics and radiographers).

Perhaps not surprisingly, diode use predominates the survey results, being used in the majority of the simpler, more established treatment techniques. The number of centres performing IVD in IMRT and VMAT cases is low compared with other photon delivery methods. No centre appears to be using only diodes for VMAT verification. A small but significant number of centres used IVD for electron beam treatments, a modality for which EPID panels do not offer an IVD solution at this time. For the VMAT radical and electron treatments, it can probably be assumed that centres with both modalities use EPID and diodes, respectively. In addition to which patient groups are assessed by IVD, the clinicians were also given a range of patient groups and asked which should be monitored with IVD (Figure A4). The majority (80%) think that all radical patients should receive IVD, although when asked whether IVD for all patients was an appropriate use of resources the split was approximately 50 : 50 (Figure A5). Most of the “no” votes were for unspecified reasons, but for most of the remainder, the main reason given for not using IVD on all patients is the reliability and false-positive rate of the current systems (discussed later in this section). It is expected that with the introduction of more reliable technologies, this ratio would shift in favour of the “yes” vote.

Figure A4.

IVD by patient group (clinicians).

The radiographer survey asked specific questions about quality management and experience in performing IVD. A total of 34 centres responded to the question about written protocols and work instructions, with all confirming they have written procedures for using IVD. When asked how long they had been performing IVD, 57% centres confirmed they had more than 5 years' experience.

When the radiographer survey asked when IVD was undertaken, 92% centres answered that they perform IVD on first fraction only, with 6% centres performing IVD on the first and second fractions and 3% centres on first, second and third fractions.

Figure A5.

Is IVD an appropriate use of resources? (clinicians).

A3. WHY DO YOU PERFORM IVD?

Table A6.

Why do you perform IVD?

| Staff group | Question | Optional answers |

|---|---|---|

| Physics and radiographers | What do you consider the main reason for undertaking IVD? | In Figure A7 |

Understanding of why IVD is being employed was questioned in both the physics and radiographer surveys, with good concordance between the two staff groups. The physics survey received responses from 33 centres with 34 centres responding to the radiographer survey (Figure A7). In each survey, it was possible to give >1 option in response. Other reasons for employing IVD were given as a clinical trial requirement, online correction of errors and cumulative dose record for TBI, and recommended good practice by Towards Safer Radiotherapy.

Figure A7.

Reasons for performing IVD (physics and radiographers).

A4. WHAT ERRORS CAN YOU DETECT?

Table A8.

Detectable errors

Both the radiographer and physics surveys asked what types of error they believed their system could identify; a total of 34 centres replied to the radiographer survey and 32 centres replied to the physics survey (Figure A9). Although this is given as a key reason for implementing IVD, there is significant disagreement regarding what errors can be detected with diode IVD. This is potentially due to different methods of use, tolerance, determination of reference dose etc., but also may be reflective of belief and trust in diodes as an effective tool for monitoring.

Many of the responses came in the form of free-text comment, and there are discrepancies between answers provided and accompanying comment. Notably, there would seem to be greater commonality of trust and belief in EPID-based systems, although this has to be viewed in the context of the low return rate for this question. Users of both technologies indicated that the capability of their system to identify certain types of error was unreliable and would depend on the nature and magnitude of the error.

A4.1. ERROR DETECTION CONTENTION

The greatest source of disagreement on detectable errors would appear to be setup errors, where there is clear disagreement over the value of diodes. Several comments suggested that setup errors detected with EPID systems were due to image acquisition, rather than the dosimetric assessment. This response would appear to be consistent with the divergent views within the RT community about the value and reliability of IVD as a quality tool.

In addition to the question about the expectations of the error detection capabilities, the physics survey also asked, as a free-text option, what types of error the local system had actually identified. The responses indicated that, consistent with Figure A12, the majority of respondents indicated never having identified an error. Of the small number that did report identifying errors (n = 5), the causes of error were identified as being incorrect Focus to Skin Distance, field size or beam energy, missing compensators and manual calculation errors. Reports of geographical miss being identified via imaging but returning a negative result using diode-based IVD do invite questions about the efficacy of using diode-based IVD in isolation.

Figure A9.

Errors detectable with IVD? (physics and radiographers).

Although the number of EPID-only responses is small, it is noted that those users consider EPIDs to be potentially more useful in capturing a wider range of errors than diodes, apart from SSD setup errors.

Of the errors found, most were attributed to manual data input and lack of electronic data transfer:

manual data transcription errors

manual calculation of MUs

incorrect construction of “in-house” lead compensator (process since discontinued)

positional setup error

incorrect field size used

incorrect FSD

wedge errors.

And others due to process errors:

underdose due to prescription error

missing bolus.

Some comments discussed errors that IVD had not found including geographical misses where diodes gave a within tolerance reading, and errors in electron treatments, not measured by IVD. Some centres using diodes for many years commented that they had never detected an error. While it is clear from the survey that IVD has a role in patient safety, there is evidence from the responses that in itself, IVD is not the panacea which can address all patient safety concerns. It is important to recognize the limitations of available systems and to view IVD in the context of the spectrum of patient safety measures.

A5. CURRENT USE OF IVD DEVICES

While 52 centres out of 65 centres answered “Yes” to performing IVD, only 35 centres reported on which devices they were using for IVD. Interestingly, 16 centres use TLDs, but all of these centres also use either diodes or EPID dosimetry. 25 centres use diode only and 7 centres are using EPID only. All centres using diodes used entrance dose, such as the point of dose maximum (Dmax), for comparison as standard (table A10). Out of the 10 centres that had EPID dosimetry as their IVD system, all carried out point dose measurements, with all using either the isocentre or another internal reference point for comparison. However, only 3 out of the 10 centres reported doing 2D planar EPID dosimetry with global gamma acceptance rates 3%/3 mm, 5%/3 mm and 4%/4 mm, respectively. This possibly reflects that historically we have come from point dose checks and the 2D or 3D EPID dosimetry option is only emerging as a new standard for IVD, but more likely this is due to the significantly higher complexity and time requirement of carrying out 2D and 3D dosimetry.

Table A10.

Where do you measure and what do you compare against?

| Staff group | Question | Optional answers |

|---|---|---|

| Physics | Centres were asked at which point they check the dose | Dmax (entrance dose) |

| Dmax (exit dose) | ||

| Isocentre | ||

| Other (free text) | ||

| Physics | What was used as the reference dose for IVD? | Point dose from TPS |

| Predicted diode dose from MU check software | ||

| Dose derived based on MU, SSD, Dmax | ||

| Other (free text) | ||

| Physics | What criteria are used if using 2D or 3D gamma analysis? | % (free text) |

| Millimetre (free text) | ||

| Local or global gamma | ||

| Physics | Which of the following are performed when performing IVD? | Independent point dose MU check |

| Pre-treatment verification |

Dmax, Dose maximum point.

Of the 35 centres that gave detailed responses, 29 centres also perform an independent point dose MU check and 12 centres also perform pre-treatment dose verification. 21 centres use a point dose calculated in their TPS as the reference and 11 centres use dose calculated by the MU check software. Only four centres used a form of manual calculation to determine the reference dose.

A6. IN VIVO PASS AND FAIL RATES

Table A11.

IVD pass and fail rates

| Staff group | Question | Optional answers |

|---|---|---|

| Physics | In the past year, what percentage of patients meet your tolerances at the first measurement? | Free text |

| Physics | In the past year, what is the (approximate) percentage of IVD reported errors that were not real? | Free text |

| Physics | Specify the main reason for false-positive results | Free text |

| Physics | What are your point dose tolerances? | Free text |

The colours in Figure A12 reflect the fraction of cases that are “true positive”, “false positive” and “negative”, and the scale is on the left-hand side, while the black line represents the tolerances used for positive/negative with the scale for tolerance on the right hand side. In addition, each centre is represented on the x-axis with the IVD device(s) used. Since the survey asked whether the IVD failure was “real”, in this case true positives are IVD failures that had a basis in real changes in dosimetry to the patient, rather than measurement error. It does not indicate whether the issue was clinically significant, requiring action.

Figure A12.

In vivo pass and fail rates (physics).

There does not appear to be a correlation between false positives and having lower tolerances, which could be expected. A 3% tolerance is only used at two centres both using EPID dosimetry. The majority of centres are using a 5% tolerance (not surprising as that is the tolerance suggested in “Towards Safer Radiotherapy”), but the amount of false positive varies quite considerably. The larger tolerances of 7%, 8% and 10% still have 5–20% “false positive”.

There were also a significant number of free-text answers provided for this section of the survey. The free-text comments about the main reasons for false-positive results detailed for diodes: position errors, particularly in the breast, steep dose gradients, particularly in chest walls, and beams exiting through attenuating material, i.e. immobilization equipment. It is worth noticing that in the centre with 90% false positives, their comment is “repeat measurements are usually within limits so position errors in the majority of cases”. For EPID, comments included air passing through bowel and weight loss. Overall, many of the causes of the failures for the EPID IVD result from changes to the patient anatomy, whereas the diode system failures result from difficulties in positioning the detector. Although some false-negative results were mentioned in the free text, these were not quantified and therefore could not be presented in the tables. Several centres also raised concerns about “error fatigue” due to the number of false positives. This adds fuel to the debate about IVD systems and their role in quality control.

Figure A13.

Point dose tolerances for IVD.

The presented tolerances (Figure A13) are those used for the majority of treatment sites at the responding centre; some stated they used different tolerances for specific sites (typical larger tolerances for breast treatments). Several centres also indicated they were considering expanding their tolerances to reduce the number of false positives. The appropriateness of a 10% tolerance is questionable and will be discussed elsewhere within this report, but the responses provided show an uncomfortably high level of false-positive results.

A7. STAFFING

Table A14.

Staff resources

| Staff group | Question | Optional answers |

|---|---|---|

| Radiographers | What were the responsibilities for the radiographers in the IVD procedure | Applying the IVD method to the patient |

| Reading and recording IVD results | ||

| Analysis of results | ||

| Acceptance of results | ||

| Checking the procedure has been carried out | ||

| Radiographers | How are the IVD results recorded in the patient treatment data? | Manually/handwritten |

| Electronically | ||

| Radiographers | How much extra time does it take the radiographers to carry out the IVD procedure | Up to 5 min |

| Between 5 min and 10 min | ||

| Radiographers | Estimate how much time is used per week for each treatment machine carrying out IVD on patients | Up to 2 man-hours per week |

| Between 2 and 4 man-hours per week | ||

| Between 4 and 8 man-hours per week | ||

| Over 8 man-hours per week |

The surveys asked specific questions about staff group responsibilities and workload implications of implementing IVD. The radiographers are heavily involved in the processing of the dosimetry results as well as the measurement acquisition in a significant number of centres (Figure A15). The recording method was 47% manually/handwritten and 53% electronically.

Figure A15.

Radiographer roles in IVD.

The radiographers were also asked about the linear accelerator time required per week (Figure A16), with most centres (71%) requiring <2 h per linear accelerator.

Figure A16.

Linear accelerator time required for IVD (radiographers).

A8. COMMISSIONING, MAINTENANCE AND PATIENT RESULT ANALYSIS

Table A17.

Time taken

| Staff group | Question | Optional answers |

|---|---|---|

| Physics | How much time was used to set up, i.e. commission and initial calibration of the IVD system in man-hours | Free text |

| Physics | How much time is spent maintaining the IVD system, i.e. recalibration, annealing, etc. in man-hours per year | Free text |

| Physics | Do you have support/maintenance from outside the hospital? | Free text |

| Physics | How much time was spent in analyzing/reading the data in both man-hours per week for the department and minutes per patient on average | Free text |

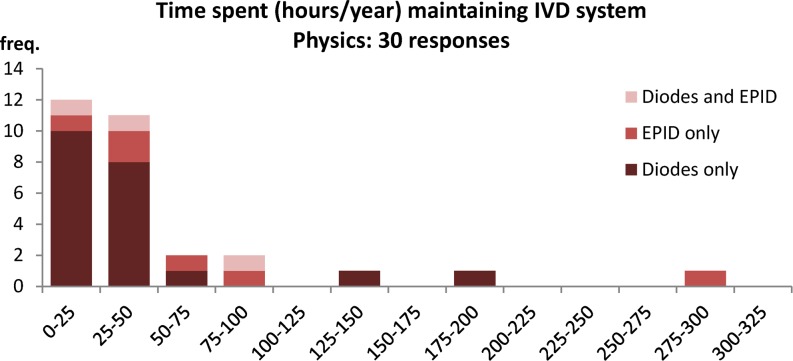

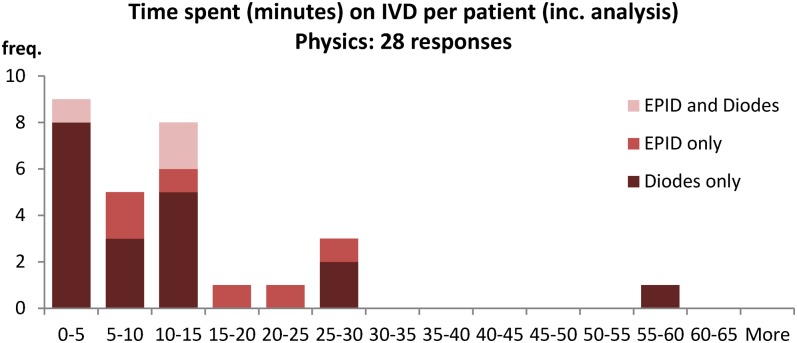

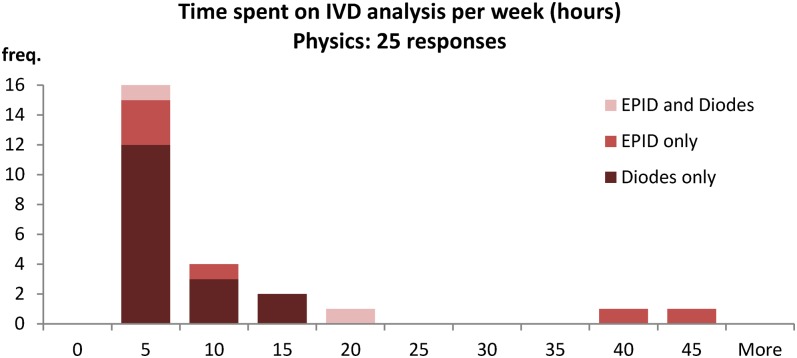

The physics survey included questions of commissioning and maintenance time (Figures A18 and A19), and the answers demonstrate that the commissioning and operational use of IVD as currently used is not overly onerous on providers, although there are outliers. The outliers are to be expected, especially for EPID systems, as some centres are involved in the development of the technology and are building experience and developing processes. Only 8 out of 33 centres that responded said they had support or maintenance from outside of the hospital for their IVD system.

Figure A18.

Time to commission IVD (physics).

Figure A19.

Time to maintain IVD (physics).

Figure A20.

Time spent on patient results (physics).

The physics survey shows the amount of time required per patient is variable, with most centres requiring <15 min per patient (79%) (Figure A12). The majority centres (80%) also spend 10 h or less on IVD analysis in a week (Figure A13). These numbers can be used to estimate the Whole Time Equivalent physicists currently used to maintain an IVD system in the majority of cases:

82% of centres spend 50 h or less a year maintaining the IVD system

80% of centres spend 10 h or less per week analyzing IVD results

0.3 WTE physicists to maintain an IVD system for most centres.

Figure A21.

Time spent on IVD per week (physics).

The total time spent on IVD per week is obviously dependent on the number of patients analyzed per week; hence, Figure A13 should indicate staff levels. Clearly, the EPID dosimetry at some centres requires extra time, which may be a reflection of it still being in the development phase.

Contributor Information

Niall D MacDougall, Email: niallmacdougall@hotmail.com, niall.macdougall@bartshealth.nhs.uk.

Michael Graveling, Email: michael.graveling@ngh.nhs.uk.

Vibeke N Hansen, Email: Vibeke.Hansen@icr.ac.uk.

Kevin Brownsword, Email: Kevin.Brownsword@hey.nhs.uk.

Andrew Morgan, Email: Andrew.Morgan@tst.nhs.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donaldson S. Towards safer radiotherapy. R Coll Radiol 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Implementing in vivo dosimetry. The Royal College of Radiologists, Society and College of Radiographers, Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine, The British Institute of Radiology; 2008.

- 3.Donaldson L. On the State of public health: Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer, Department of Health; 2006.

- 4. Vision for Radiotherapy Report. CRUK; 2014. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/policy_feb2014_radiotherapy_vision2014-2024_final.pdf.

- 5.Fiorino C, Corletto D, Mangili P, Broggi S, Bonini A, Cattaneo GM, et al. Quality assurance by systematic in vivo dosimetry: results on a large cohort of patients. Radiother Oncol 2000; 56: 85–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8140(00)00195-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackay RI, Williams PC. The cost effectiveness of in vivo dosimetry is not proven. Br J Radiol 2009; 82: 265–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/58443203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison R, Morgan A. In vivo dosimetry: hidden dangers? Br J Radiol 2007; 80: 691–2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/24873815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein EE, Drzymala RE, Purdy JA, Michalski JM. Errors in radiation oncology: a study in pathways and dosimetric impact. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2005; 6: 81–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1120/jacmp.2025.25355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manual for cancer services: radiotherapy measures. NCAT; Available from: http://www.mycancertreatment.nhs.uk/wp-content/themes/mct/uploads/2012/09/resources_measures_Radiotherapy_Measures_April2011.pdf.

- 10.Edwards CR, Hamer E, Mountford PJ, Moloney AJ. An update survey of UK in vivo radiotherapy dosimetry practice. Br J Radiol 2007; 80: 1011–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/14945156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. IAEA. Development of procedures for in vivo dosimetry in radiotherapy. IAEA; 2013. (IAEA Human Health Reports). Report no. 8. Available from: http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/Pub1606_web.pdf.

- 12.Nilsson B, Rudén BI, Sorcini B. Characteristics of silicon diodes as patient dosemeters in external radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol 1988; 11: 279–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8140(88)90011-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noel A, Aletti P, Bey P, Malissard L. Detection of errors in individual patients in radiotherapy by systematic in vivo dosimetry. Radiother Oncol 1995; 34: 144–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8140(94)01503-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calandrino R, Cattaneo GM, Fiorino C, Longobardi B, Mangili P, Signorotto P. Detection of systematic errors in external radiotherapy before treatment delivery. Radiother Oncol 1997; 45: 271–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00095-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards C, Grieveson M, Mountford P, Rolfe P. A survey of current in vivo radiotherapy dosimetry practice. Br J Radiol 1997; 70: 299–302. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.70.831.9166056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yorke E, Alecu R, Ding L, Boissoneault R, Fontenla D, Kalend A, et al. Diode in vivo dosimetry for patients receiving external beam radiation therapy. Report of Task Group 62; 2005.

- 17.Alaei P, Higgins PD, Gerbi BJ. In vivo diode dosimetry for IMRT treatments generated by Pinnacle treatment planning system. Med Dosim 2009; 34: 26–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meddos.2008.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinall A, Williams A, Currie V, Van Esch A, Huyskens D. Practical guidelines for routine intensity-modulated radiotherapy verification: pre-treatment verification with portal dosimetry and treatment verification with in vivo dosimetry. Br J Radiol 2010; 83: 949–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/31573847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mijnheer B, Beddar S, Izewska J, Reft C. In vivo dosimetry in external beam radiotherapy. Med Phys 2013; 40: 070903. doi: https://doi.org/10.1118/1.4811216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinkerton A, Hannon M, Kwag J, Renner WD. Experience using Dosimetrycheck software for IMRT and RapidArc patient pre-treatment QA and a new feature for QA during treatment. J Phys Conf Ser 2010; 250: 012101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/250/1/012101 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolini G, Fogliata A, Vanetti E, Clivio A, Cozzi L. GLAaS: an absolute dose calibration algorithm for an amorphous silicon portal imager. applications to IMRT verifications. Med Phys 2006; 33: 2839–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1118/1.2218314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narayanasamy G, Zalman T, Ha CS, Papanikolaou N, Stathakis S. Evaluation of Dosimetrycheck software for IMRT patient-specific quality assurance. J Appl Clin Med Phys 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boissard P, François P, Rousseau V, Mazal A. Evaluation and implementation of in vivo transit dosimetry with an electronic portal imaging device. [In French.] Cancer Radiother 2013; 17: 656–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canrad.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ricketts K, Navarro C, Lane K, Blowfield C, Cotten G, Tomala D, et al. Clinical experience and evaluation of patient treatment verification with a transit dosimeter. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013; 95: 1513–19. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricketts K, Navarro C, Lane K, Moran M, Blowfield C, Kaur U, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a transit dosimetry system for treatment verification. Phys Med 2016; 32: 671–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmp.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wendling M, McDermott LN, Mans A, Sonke JJ, van Herk M, Mijnheer BJ. A simple backprojection algorithm for 3D in vivo EPID dosimetry of IMRT treatments. Med Phys 2009; 36: 3310–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1118/1.3148482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olaciregui-Ruiz I, Rozendaal R, Mijnheer B, van Herk M, Mans A. Automatic in vivo portal dosimetry of all treatments. Phys Med Biol 2013; 58: 8253. doi: https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/58/22/8253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mijnheer BJ, González P, Olaciregui-Ruiz I, Rozendaal RA, van Herk M, Mans A. Overview of 3-year experience with large-scale electronic portal imaging device-based 3-dimensional transit dosimetry. Pract Radiat Oncol 2015; 5: e679–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prro.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munro AJ. Hidden danger, obvious opportunity: error and risk in the management of cancer. Br J Radiol 2007; 80: 955–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/12777683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Intensity Modulated Radiotherapy (IMRT) in the UK: current access and predictions of future access rates. Radiotherapy Board; [Cited 9 October 2015]. Available from: http://www.ipem.ac.uk/Portals/0/Documents/Partners/Radiotherapy%20Board/imrt_target_revisions_recommendations_for_colleges_final2.pdf.