Abstract

Objective:

To analyze intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs) and extramyocellular lipids (EMCLs) of the multifidus muscle (Mm) using MR spectroscopy in chronic low back pain (CLBP) and control groups and to identify correlations with spinopelvic alignment.

Methods:

40 patients (16 males, 24 females; mean age, 62.9 ± 1.9 years) whose visual analogue scale scores were >30 mm for CLBP were included. Furthermore, 40 control participants matched with the CLBP group subjects by sample size, gender and age (17 males, 23 females; mean age, 65.0 ± 1.2 years) were included. We compared the body mass index, physical workload, leisure time physical activity level, spinopelvic parameters, and IMCLs and EMCLs of the Mm between the groups. We also evaluated possible correlations of spinopelvic parameters with IMCLs and EMCLs of the Mm in the groups.

Results:

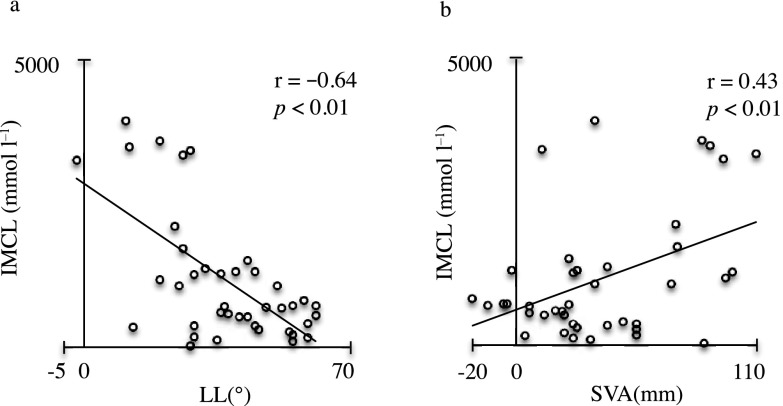

There were no statistically significant differences in body mass index, physical workload, exercise intensity level, spinopelvic parameters and EMCLs between the groups. The IMCLs were significantly higher in the CLBP group than in the control group (p < 0.01). In the CLBP group, there was a significantly negative correlation between IMCLs and lumbar lordosis (r = −0.64, p < 0.01) and a significantly positive correlation between IMCLs and sagittal vertical axis (r = 0.43, p < 0.01).

Conclusion:

The measurement of IMCLs might be a characteristic finding of CLBP as well as a precursor to spinal deformity.

Advances in knowledge:

IMCLs of the Mm may be a useful prognostic marker in rehabilitation strategies for patients with CLBP.

INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) is a common condition and is one of the most serious physiological problems worldwide.1–3 However, the cause of LBP is rarely identified in individual patients.4 Trunk muscles are important for normal spinal function and aetiologically significant in LBP.5 In particular, the multifidus muscle (Mm) provides two-thirds of spinal segmental stability6 and is important for the maintenance of spinal alignment.7 Evaluation of Mm function forms a part of the clinical assessment of patients with LBP8 and changes in Mm function are related to the outcome following conservative therapy.5,9 Considering these observations, we hypothesized that Mm dysfunction causes spinal malalignment relating to chronic LBP (CLBP). MRI is useful for analyzing fat degeneration of the Mm.10–12 Recently, in addition to morphological assessments, muscles have been evaluated using MRI with the multipoint Dixon technique12,13 and MR spectroscopy (MRS).10,14 MRS analysis of muscle physiology has been used in various fields, such as sports medicine,15–17 and has facilitated detailed analyses of muscular fat masses by recording the presence of intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs) and extramyocellular lipids (EMCLs); this has helped to identify detail of fatty degeneration.6,18 IMCLs cannot be visually detected using conventional MRI because they are stored in spheroid droplets in the cytoplasm of muscle cells in close contact with skeletal mitochondria18,19 and are directly used as an energy source by mitochondria. Therefore, IMCLs are involved in the increase of free fatty acids in the blood, the increase in their uptake by skeletal muscles and their decreased oxidative capacity.16,20 Physical inactivity has adverse effects on skeletal muscle metabolism, manifesting as poor oxidative capacity,21,22 lower glycogen storage and decreased capillary density.23 By contrast, EMCLs are defined as more or less compact areas of adipose tissue in subcutaneous layers or along fasciae and are considered to be metabolically inactive lipid deposits involved in the reduced functionality associated with obesity and a sedentary lifestyle.6,20,24 Lost muscle strength is associated with the accumulation of EMCLs, which can interfere with sufficient muscle nutrition.6,24,25 We previously reported that IMCLs using MRS analysis in the Mm of patients with CLBP were significantly higher than in asymptomatic volunteers.26 Some reports have described the associations of spinopelvic alignment with LBP27–29 and fatty atrophy of Mm;7,30 however, the association of IMCLs and EMCLs with spinopelvic alignment in patients with CLBP remains unclear. The aims of the present study were to analyze IMCLs and EMCLs of the Mm using MRS in CLBP and control groups and to identify possible correlations with spinopelvic alignment.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The institutional review board of the Sapporo Medical University approved this study. All participants were provided with written and verbal explanations of the study, and they provided their consent before study initiation.

Participants

The subjects comprised patients (aged 41–79 years) who had non-specific CLBP that had persisted for 3 months and more and whose symptoms did not improve with conservative treatments. All subjects underwent radiographic examination and MRI of the lumbar spine and completed the LBP visual analogue scale (VAS) scores (0–100 mm) after a washout period of at least 4 weeks. The following inclusion criteria: (a) VAS scores of >30 mm, (b) no prior spine surgery, (c) no systemic inflammatory disease, (d) no neurological disorders, (e) no acute trauma, neoplasm or infection, (f) no history of spinal fracture, (g) no scoliosis, (h) Modic change31 or (i) no advanced disc degeneration (Pfirrmann grade V32). 40 patients (16 males, 24 females; mean age, 62.9 ± 1.9 years; range 41–79 years) satisfied the diagnostic criteria. As a control group, this study also involved 40 patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) whose VAS scores were <30 mm. All patients had intermittent claudication with lower extremity symptoms for cauda equina syndrome. They were matched to the CLBP group subjects by sample size, gender and age (17 males, 23 females; mean age, 65.0 ± 1.2 years; range, 42–77 years).

Self-report measures

We calculated the body mass index (BMI) as self-reported body weight (kg) divided by the height squared (m2) as an indicator of obesity, which is associated with the fat content. Information related to physical workload and exercise intensity level was collected, referring to a previous report.33 In order to assess the physical workload, four various alternatives based on the vocational activities could be selected: sedentary work or resignation; light physical work such as official work, teaching and salesclerk, where they walked a lot and carried light loads; moderate heavy work such as healthcare, plumbery and woodwork, where they walked a lot and carried heavy loads; and heavy work such as husbandry, building operation, fishery and forest operation, where they carried many heavy loads and experienced many physical burdens. In order to assess the exercise intensity, five various options could be selected: almost nothing; occasionally a saunter; light physical exertion such as walking, bicycling, dancing and fishing for at least 2 h per week; moderate physical exertion such as gymnastics, swimming, tennis, soccer and running for less than 2 h per week; high physical exertion such as gymnastics, swimming, tennis, soccer and running for more than 2 h per week.

Radiographic evaluation

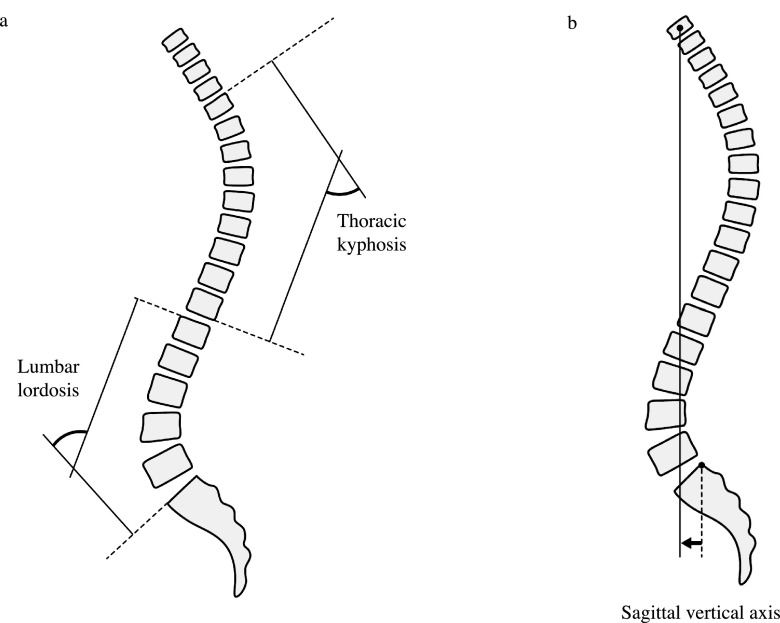

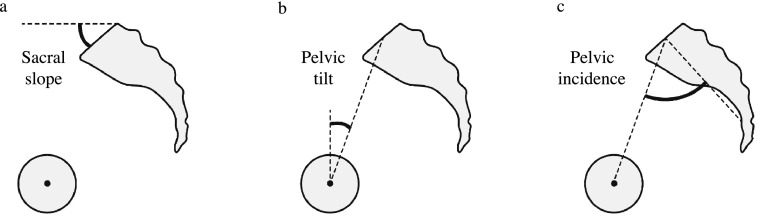

We measured the full length of the spine and pelvis radiographs of the subjects in a standing position to determine several parameters, referring to a previous report.34 The following sagittal spinal radiological parameters (Figure 1) were recorded from the sagittal plane of spine radiographs: lumbar lordosis (LL; the superior endplate of L1 to the superior endplate of S1, Figure 1a), thoracic kyphosis (TK; the superior endplate of T4 to the inferior endplate of T12, Figure 1a) and sagittal vertical axis (SVA; the horizontal offset from the posterior–superior corner of S1 to the vertebral midbody of C7, Figure 1b). The following sagittal pelvic parameters (Figure 2) were recorded from the sagittal plane of pelvic radiographs: sacral slope (SS; the angle between the horizontal and upper sacral endplate, Figure 2a), pelvic tilt (PT; the angle between the vertical plate and the line through the midpoint of the sacral plate to the femoral head axis, Figure 2b) and pelvic incidence (PI; the angle perpendicular to the upper sacral endplate at its midpoint and the line connecting this point to the femoral head axis, Figure 2c). Intra- and interobserver reliabilities for the measurement of spinopelvic parameters were assessed blindly by two investigators (Observer 1: IO and Observer 2: HT).

Figure 1.

Sagittal spinal radiologic parameters were recorded as follows: (a) lumbar lordosis (the superior endplate of L1 to the superior endplate of S1) and thoracic kyphosis (the superior endplate of T4 to the inferior endplate of T12), and (b) sagittal vertical axis (the horizontal offset from the posterior–superior corner of S1 to the vertebral midbody of C7).

Figure 2.

Pelvic parameters were recorded as follows: (a) sacral slope (the angle between the horizontal and upper sacral endplate), (b) pelvic tilt (the angle between the vertical and line through the midpoint of the sacral plate to the femoral head axis) and (c) pelvic incidence (the angle perpendicular to the upper sacral endplate at its midpoint and the line connecting this point to the femoral head axis).

MRI protocol and analysis for MR spectroscopic data

We used the MRI protocol and methods of analysis for MR spectroscopic data which had been previously described.26 In brief, the Signa HDx 1.5-T MRI system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) with a spine coil was used to obtain T2 weighted sagittal and transverse MR images. From these images, the proton MRS volume of interest (VOI) was positioned in the centre of the Mm at L4/L5 for the right side (Figure 3). Single-voxel point-resolved spectroscopy sequence was performed with the following parameters: repetition time, 2000 ms; echo time, 35 ms; average number of signals, 64; VOI size, 15 × 15 × 15 mm (3.4 ml); and acquisition time, 164 s.

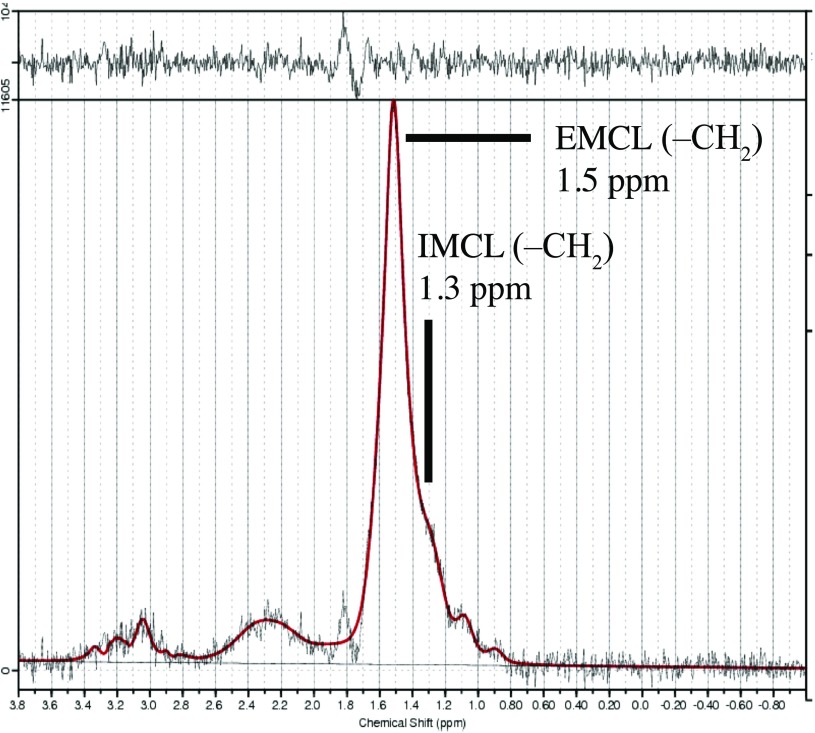

Figure 3.

Volume of interest for MR spectroscopy measurements was set right of the multifidus muscle as indicated on the T2 weighted image at the L4/L5 level.

The spectral data obtained were used to measure IMCL and EMCL using the LCModel software (Stephen Provencher, Inc., Oakville, ON). Data were transferred from the scanners to a Linux workstation, and metabolite quantification was performed by eddy current correction and water scaling. Data for IMCL (1.3 ppm) and EMCL (1.5 ppm) corresponding to methylene protons were used for statistical analysis. Estimates of IMCL and EMCL were automatically scaled to an unsuppressed water peak (4.7 ppm) and expressed in institutional units. These data are displayed graphically with the chemical shift along the x-axis, allowing the identification of metabolites. Peak intensity is plotted on the y-axis (Figure 4). We excluded subjects in whom the Mm was shown a standard deviation of over 15% for EMCL or IMCL on the LCModel.

Figure 4.

Proton MR spectrum of the Mm analyzed using LCModel software (Stephen Provencher, Inc., Oakville, ON). The following metabolites are identified: intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs) (–CH2) methylene protons at 1.3 ppm; extramyocellular lipids (EMCLs) (–CH2) methylene protons at 1.5 ppm.

Statistical analysis

We compared BMI, work, exercise frequency, spinopelvic parameters, and IMCLs and EMCLs of the Mm between the CLBP and control groups. χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U test were used for significant difference testing. We also compared possible correlations of spinopelvic parameters with IMCLs and EMCLs of the Mm in the CLBP and control groups using Pearson's correlation coefficient test. p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. All numerical data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, the mean BMI of the CLBP group was 23.9 ± 0.6 kg m−2 and that of the control group was 23.3 ± 0.5 kg m−2, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.76). The mean VAS score of the CLBP group was 68.1 ± 2.6 mm and that of the control group was 12.3 ± 1.3 mm (p < 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences in physical workload and exercise intensity level between the groups (p = 0.59 and p = 0.93).

Table 1.

Distribution of the examinees with regard to the gender, age, body mass index (BMI), visual analogue scale (VAS), physical workload and leisure-time physical activity level

| Characteristics | CLBP (n = 40) | Control (n = 40) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M : F) | 16 : 24 | 17 : 23 | 0.82a |

| Age (years) | 62.9 ± 1.9 | 65.0 ± 1.2 | 0.60b |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 23.9 ± 0.6 | 23.3 ± 0.5 | 0.76b |

| VAS (mm) | 68.1 ± 2.6 | 12.3 ± 1.3 | <0.01b |

| Physical workload | |||

| Sedentary work/resignation | 30 | 29 | 0.59a |

| Light physical work | 9 | 9 | |

| Moderate heavy work | 1 | 2 | |

| Heavy work | 0 | 0 | |

| Leisure-time physical activity level | |||

| Almost nothing | 31 | 32 | 0.93a |

| Occasionally a saunter | 8 | 7 | |

| Light physical exertion | 1 | 1 | |

| Moderate physical exertion | 0 | 0 | |

| High physical exertion | 0 | 0 | |

CLBP, chronic low back pain; F, female; M, male.

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

χ2 test.

Mann–Whitney U test.

For the CLBP and control groups, the following results were, respectively, obtained for spinopelvic parameters: LL, 37.6 ± 2.5° and 40.7 ± 2.2°; TK, 31.0 ± 2.0° and 31.6 ± 2.2°; SVA, 38.6 ± 5.4 and 33.4 ± 4.8 mm; SS, 28.8 ± 1.4° and 29.9 ± 1.2°; PT, 21.0 ± 1.6° and 20.5 ± 1.3°; and PI, 49.8 ± 1.5° and 49.2 ± 1.9° (Table 2). There were no statistically significant differences in spinopelvic parameters between the groups (LL, p = 0.44; TK, p = 0.99; SVA, p = 0.47; SS, p = 0.55; PT, p = 0.88; and PI, p = 0.98).

Table 2.

Comparisons of spinopelvic parameters in the chronic low back pain (CLBP) and control groups

| Spinopelvic parameters | CLBP (n = 40) | Control (n = 40) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LL (°) | 37.6 ± 2.5 | 40.7 ± 2.2 | 0.44a |

| TK (°) | 31.0 ± 2.0 | 31.6 ± 2.2 | 0.99a |

| SVA (mm) | 38.6 ± 5.4 | 33.4 ± 4.8 | 0.47a |

| SS (°) | 28.8 ± 1.4 | 29.9 ± 1.2 | 0.55a |

| PT (°) | 21.0 ± 1.6 | 20.5 ± 1.3 | 0.88a |

| PI (°) | 49.8 ± 1.5 | 49.2 ± 1.9 | 0.98a |

LL, lumbar lordosis; PI, pelvic incidence; PT, pelvic tilt; SS, sacral slope; SVA, sagittal vertical axis; TK, thoracic kyphosis.

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Mann–Whitney U test.

For the intra- and interobserver reliabilities, the following results were, respectively, obtained: LL, 0.85 and 0.91; TK, 0.89 and 0.92; SVA, 0.84 and 0.91; SS, 0.83 and 0.90; PT, 0.85 and 0.88; and PI, 0.81 and 0.87 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Intra- and interobserver reliabilities analysis

| Spinopelvic parameters | Intraobserver reliability (Observer 1/Observer 2) | Interobserver reliability (Observer 1/Observer 1) |

|---|---|---|

| LL (°) | 0.85 | 0.91 |

| TK (°) | 0.89 | 0.92 |

| SVA (mm) | 0.84 | 0.91 |

| SS (°) | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| PT (°) | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| PI (°) | 0.81 | 0.87 |

LL, lumbar lordosis; PI, pelvic incidence; PT, pelvic tilt; SS, sacral slope; SVA, sagittal vertical axis; TK, thoracic kyphosis.

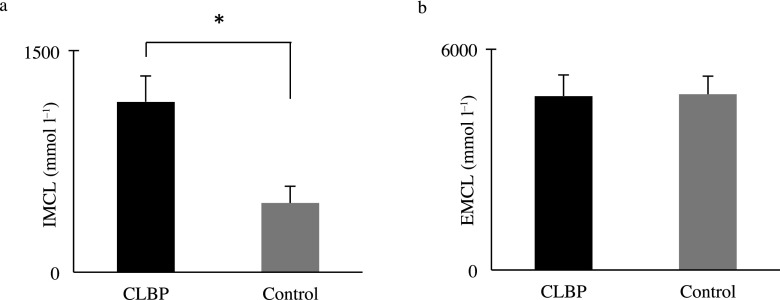

The mean IMCLs of the Mm for the CLBP and control groups were 11.6 ± 1.85 (×102) and 4.70 ± 1.13 (×102) mmol l−1, respectively. The IMCLs were significantly higher in the CLBP group than in the control group (p < 0.01) (Figure 5a). The mean EMCLs of the Mm in the CLBP and control groups were 4.72 ± 0.57 (×103) and 4.77 ± 0.50 (×103) mmol l−1, respectively, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.71) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Comparisons of (a) intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs) and (b) extramyocellular lipids (EMCLs) of the multifidus muscle in the chronic low back pain (CLBP) and control groups. IMCLs were higher in the CLBP group, and EMCLs were not significantly difference between the CLBP and control groups. Data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.01 CLBP vs control: Mann–Whitney U test.

In the CLBP group, there was a significantly negative correlation between IMCLs and LL (r = −0.64, p < 0.01, Figure 6a). There was a significantly positive correlation between IMCL and SVA (r = 0.43, p < 0.01, Figure 6b). There were no significant correlations between IMCLs and TK (r = 0.02, p = 0.90), SS (r = −0.15, p = 0.36), PT (r = 0.11, p = 0.50) and PI (r = −0.08, p = 0.64). There were no significant correlations between EMCLs and LL (r = 0.15, p = 0.37), TK (r = 0.19, p = 0.23), SVA (r = 0.02, p = 0.91), SS (r = 0.09, p = 0.58), PT (r = 0.15, p = 0.34) and PI (r = 0.10, p = 0.54) (Table 4).

Figure 6.

Relationship among intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs), lumbar lordosis (LL) and sagittal vertical axis (SVA) in the chronic low back pain group. (a) The correlation coefficient between IMCLs and LL indicated significantly negative correlation. (b) The correlation coefficient between IMCL and SVA indicated significantly positive correlation.

Table 4.

Pearson's correlation coefficient of spinopelvic parameters with intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs) and extramyocellular lipids (EMCLs) of the multifidus muscle in the chronic low back pain group

| Spinopelvic parameters | IMCL |

EMCL |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |

| LL (°) | −0.64 | <0.01 | 0.15 | 0.37 |

| TK (°) | 0.02 | 0.90 | 0.19 | 0.23 |

| SVA (mm) | 0.43 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.91 |

| SS (°) | −0.15 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.58 |

| PT (°) | 0.11 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.34 |

| PI (°) | −0.08 | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.54 |

LL, lumbar lordosis; PI, pelvic incidence; PT, pelvic tilt; SS, sacral slope; SVA, sagittal vertical axis; TK, thoracic kyphosis.

In the control group, there were no significant correlations between IMCLs and LL (r = 0.20, p = 0.22), TK (r = 0.09, p = 0.58), SVA (r = −0.20, p = 0.22), SS (r = 0.08, p = 0.64), PT (r = −0.06, p = 0.70) and PI (r = 0.06, p = 0.70). There were no significant correlations between EMCLs and LL (r = 0.09, p = 0.57), TK (r = 0.04, p = 0.81), SVA (r = 0.12, p = 0.45), SS (r = 0.10, p = 0.56), PT (r = −0.01, p = 0.54) and PI (r = −0.12, p = 0.45) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pearson's correlation coefficient of spinopelvic parameters with intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs) and extramyocellular lipids (EMCLs) of the multifidus muscle in the control group

| Spinopelvic parameters | IMCL |

EMCL |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | |

| LL (°) | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.57 |

| TK (°) | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.04 | 0.81 |

| SVA (mm) | −0.20 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.45 |

| SS (°) | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.10 | 0.56 |

| PT (°) | −0.06 | 0.70 | −0.01 | 0.54 |

| PI (°) | 0.06 | 0.70 | −0.12 | 0.45 |

LL, lumbar lordosis; PI, pelvic incidence; PT, pelvic tilt; SS, sacral slope; SVA, sagittal vertical axis; TK, thoracic kyphosis.

DISCUSSION

Several previous studies have reported an association between LBP and fat degeneration in the paraspinal muscles using various indicators and imaging techniques, all revealing an increase in fat degeneration.10,12,35,36 The majority of those studies used the fat fraction of the multipoint Dixon technique to assess degeneration, whereas studies using MRS comprehensively evaluated degeneration as the overall amount of fat content. While in the present study, adipose tissue was distinguished from IMCLs and EMCLs as fat content in Mm.

In this cross-sectional and comparative study, we analyzed IMCLs and EMCLs of the Mm using MRS in the CLBP and the control groups and identified correlations with spinopelvic parameters. There were two extremely fascinating findings in the present study. The first was that quantitative analysis showed that IMCLs of the Mm were significantly higher in the CLBP group than in the control group. The second was that we identified the correlations between LL and SVA and IMCLs of the Mm in the CLBP group and found no correlations between spinopelvic parameters and IMCLs of the Mm in the control group. Several clinical studies have demonstrated associations of spinopelvic parameters with LBP.27–29 However, there was no statistical difference between the CLBP group and the control group in the spinopelvic parameters in this study. Patients with LSS present forward-bending posture because epidural pressure decreases by lumbar flexion, and their leg symptoms improve.37,38 This explained that the control group had similar spinopelvic parameters with the CLBP group. Considering the similar spinopelvic parameters in the two groups, just a spinopelvic malalignment was not the cause of CLBP. The measurement of IMCLs may be a characteristic finding of CLBP. A new question arises as to whether an increase in IMCLs of the Mm was the cause or the result of spinopelvic malalignment. IMCLs have been previously associated with aerobic metabolism,6,16 and they reportedly decrease post exercise.39–41 From these observations, we speculated that IMCLs decrease in response to continuous eccentric contraction if the deformity has occurred earlier than the functional loss of the Mm. Consequently, we surmised that spinal deformity can be a result of Mm dysfunction in subjects with CLBP before structural deformities develop.

Disc degeneration42 and collapsed vertebral bodies43 irreversibly develop with advancing age; however, an increase in IMCLs of the Mm can probably improve if conservative treatments, such as therapeutic exercise, are initiated. Because of the correlations between LL and SVA and IMCLs of the Mm in the CLBP group, it is expected that therapeutic exercises can improve CLBP and spinal deformities, such as lumbar kyphosis and a forward-bent posture without structural deformity. IMCLs of the Mm may be a useful prognostic marker in rehabilitation strategies for patients with CLBP. The ultimate goal of the study in future is to enhance exercise strategies with IMCLs and spinopelvic parameters as indexes to treat CLBP.

In this study, we analyzed lipid content of the Mm as IMCLs and EMCLs using MRS; however, there have been newer methods such as chemical shift MRI to assess more accurate muscle fat content recently.12 It was expected that chemical shift MRI, for example, two-point or multipoint Dixon could demonstrate the more accurate fat content of the Mm. Additionally, T2* and R2* of Mm using multipoint Dixon quantitative imaging could have higher reliability. We conducted no comparison analyses between MRS and such newer techniques. However, Fischer et al10 compared lumbar muscle fat-signal fractions derived from three-dimensional dual gradient-echo MRI and multiple gradient-echo MRI with fractions from single-voxel MRS in patients with LBP. They showed that strong correlation between spectroscopic and all imaging-based fat-signal fractions and the very narrow range of observed R2* and T2* values in the lumbar muscle were largely independent of fat content. They considered that the finding was consistent with results from an ex vivo study that compared different fat quantification methods and used MRS as the standard of reference44 and would appear to slightly reduce the importance of a T2* correction in estimations of muscle-fat content compared with, for example, liver-fat content.45 Therefore, we predicted that Mm lipid estimates, derived from multiecho acquisition with water and fat signal-separating reconstruction corrected for multiple fat spectral lines, were similar to spectroscopic fat measurements. In this study, adipose tissue was distinguished from IMCLs and EMCLs as fat content in the Mm, whereas previous studies using these techniques reported increased fat content as the total amount of adipose tissue.

This study had several limitations. First, the control group of this study was not asymptomatic volunteers but patients with LSS. We previously reported that IMCLs using MRS analysis in the Mm of patients with CLBP was significantly higher than that of asymptomatic volunteers.26 However, sagittal spinopelvic alignment tended to be different between patients with chronic LBP and asymptomatic volunteers.27 Therefore, we needed the control group with the same sagittal spinopelvic alignment as the CLBP group to investigate the connection among IMCLs, EMCLs and CLBP. Second, we positioned the VOI and measured IMCLs and EMCLs once only at the L4 through L5 level because pathological change appears most often at that location based on previous reports.10,46,47 At this level, the paraspinal muscle is the main muscle protecting the spinal structure controlling the gliding motion in all lumbar vertebrae.48,49 Intra- and interobserver reliabilities studies indicated that the inherent error of the IMCLs measurement is about 6%.19,50 Therefore, we consider that measurement of IMCLs in the present study was possible to accurately assess. Third, this was a cross-sectional study; a longitudinal study design would have been a better choice. We expected that the measurement of IMCLs might be a characteristic finding of CLBP as well as a precursor to spinal deformity. To validate this point, future studies are needed to confirm the relationships among IMCLs, spinopelvic alignment, clinical symptoms and functional changes in the lumbar spine.

CONCLUSIONS

Quantitative analysis of IMCLs and EMCLs from muscle fat revealed that the IMCLs of the Mm were significantly higher in the CLBP group than in the control group. We identified correlations between LL and SVA in IMCLs of the Mm in the CLBP group and found no correlations between spinopelvic parameters and IMCLs of the Mm in the control group. The measurement of IMCLs might be a characteristic finding of CLBP as well as a precursor to spinal deformity.

FUNDING

The project was funded by the Nakatomi Foundation.

Contributor Information

Izaya Ogon, Email: ogon.izaya@sapmed.ac.jp.

Tsuneo Takebayashi, Email: takebaya@sapmed.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Takashima, Email: takashima@sapmed.ac.jp.

Tomonori Morita, Email: tomonori.morita1031@gmail.com.

Mitsunori Yoshimoto, Email: myoshimo@sapmed.ac.jp.

Yoshinori Terashima, Email: ytera@zf6.so-net.ne.jp.

Toshihiko Yamashita, Email: tyamasit@sapmed.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deyo RA, Weinstein JN. Low back pain. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 363–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200102013440508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurwitz EL, Morgenstern H. The effects of comorbidity and other factors on medical versus chiropractic care for back problems. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997; 22: 2254–63; discussion 2263–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shekelle PG, Markovich M, Louie R. An epidemiologic study of episodes of back pain care. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995; 20: 1668–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balague F, Mannion AF, Pellise F, Cedraschi C. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2012; 379: 482–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cholewicki J, Panjabi MM, Khachatryan A. Stabilizing function of trunk flexor-extensor muscles around a neutral spine posture. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997; 22: 2207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boesch C, Machann J, Vermathen P, Schick F. Role of proton MR for the study of muscle lipid metabolism. NMR Biomed 2006; 19: 968–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takemitsu Y, Harada Y, Iwahara T, Miyamoto M, Miyatake Y. Lumbar degenerative kyphosis. Clinical, radiological and epidemiological studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988; 13: 1317–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hebert JJ, Koppenhaver SL, Teyhen DS, Walker BF, Fritz JM. The evaluation of lumbar multifidus muscle function via palpation: reliability and validity of a new clinical test. Spine J 2015; 15: 1196–202. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.08.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritz JM, Koppenhaver SL, Kawchuk GN, Teyhen DS, Hebert JJ, Childs JD. Preliminary investigation of the mechanisms underlying the effects of manipulation: exploration of a multivariate model including spinal stiffness, multifidus recruitment, and clinical findings. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011; 36: 1772–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318216337d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer MA, Nanz D, Shimakawa A, Schirmer T, Guggenberger R, Chhabra A, et al. Quantification of muscle fat in patients with low back pain: comparison of multi-echo MR imaging with single-voxel MR spectroscopy. Radiology 2013; 266: 555–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.12120399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kjaer P, Bendix T, Sorensen JS, Korsholm L, Leboeuf-Yde C. Are MRI-defined fat infiltrations in the multifidus muscles associated with low back pain? BMC Med 2007; 5: 2. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-5-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanik B, Keyik B, Conkbayir I. Fatty degeneration of multifidus muscle in patients with chronic low back pain and in asymptomatic volunteers: quantification with chemical shift magnetic resonance imaging. Skeletal Radiol 2013; 42: 771–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-012-1545-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paalanne N, Niinimaki J, Karppinen J, Taimela S, Mutanen P, Takatalo J, et al. Assessment of association between low back pain and paraspinal muscle atrophy using opposed-phase magnetic resonance imaging: a population-based study among young adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011; 36: 1961–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181fef890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mengiardi B, Schmid MR, Boos N, Pfirrmann CW, Brunner F, Elfering A, et al. Fat content of lumbar paraspinal muscles in patients with chronic low back pain and in asymptomatic volunteers: quantification with MR spectroscopy. Radiology 2006; 240: 786–92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2403050820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bredella MA, Ghomi RH, Thomas BJ, Miller KK, Torriani M. Comparison of 3.0 T proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy short and long echo-time measures of intramyocellular lipids in obese and normal-weight women. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 32: 388–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, Hesselink MK, Schrauwen P, Kooi ME. Intramyocellular lipid content in human skeletal muscle. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006; 14: 357–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Bredella MA, Ouellette H. Intramyocellular lipid quantification: comparison between 3.0- and 1.5-T (1)H-MRS. Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 25: 1105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boesch C. Musculoskeletal spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 25: 321–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.20806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boesch C, Kreis R. Observation of intramyocellular lipids by 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000; 904: 25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srikanthan P, Singhal A, Lee CC, Nagarajan R, Wilson N, Roberts CK, et al. Characterization of Intra-myocellular Lipids using 2D Localized Correlated Spectroscopy and Abdominal Fat using MRI in Type 2 Diabetes. Magn Reson Insights 2012; 5: 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dube JJ, Amati F, Stefanovic-Racic M, Toledo FG, Sauers SE, Goodpaster BH. Exercise-induced alterations in intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance: the athlete's paradox revisited. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 294: E882–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00769.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konopka AR, Suer MK, Wolff CA, Harber MP. Markers of human skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and quality control: effects of age and aerobic exercise training. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci 2014; 69: 371–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glt107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoladz JA, Semik D, Zawadowska B, Majerczak J, Karasinski J, Kolodziejski L, et al. Capillary density and capillary-to-fibre ratio in vastus lateralis muscle of untrained and trained men. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2005; 43: 11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velan SS, Said N, Durst C, Frisbee S, Frisbee J, Raylman RR, et al. Distinct patterns of fat metabolism in skeletal muscle of normal-weight, overweight, and obese humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 295: R1060–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.90367.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jucker BM, Schaeffer TR, Haimbach RE, Mayer ME, Ohlstein DH, Smith SA, et al. Reduction of intramyocellular lipid following short-term rosiglitazone treatment in Zucker fatty rats: an in vivo nuclear magnetic resonance study. Metabolism 2003; 52: 218–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/meta.2003.50040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takashima H, Takebayashi T, Ogon I, Yoshimoto M, Terashima Y, Imamura R, et al. Evaluation of intramyocellular and extramyocellular lipids in the paraspinal muscle in patients with chronic low back pain using MR spectroscopy: preliminary results. Br J Radiol 2016; 89: 20160136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaleat-Valayer E, Mac-Thiong JM, Paquet J, Berthonnaud E, Siani F, Roussouly P. Sagittal spino-pelvic alignment in chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2011; 20(Suppl. 5): 634–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-011-1931-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Araujo F, Lucas R, Alegrete N, Azevedo A, Barros H. Sagittal standing posture, back pain, and quality of life among adults from the general population: a sex-specific association. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014; 39: E782–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson RP, McManus AC. Radiographic analysis of sagittal plane alignment and balance in standing volunteers and patients with low back pain matched for age, sex, and size. A prospective controlled clinical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994; 19: 1611–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyun SJ, Bae CW, Lee SH, Rhim SC. Fatty degeneration of the paraspinal muscle in patients with degenerative lumbar kyphosis: a new evaluation method of quantitative digital analysis using MRI and CT scan. Clin Spine Surg 2016; 29: 441–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BSD.0b013e3182aa28b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Modic MT, Steinberg PM, Ross JS, Masaryk TJ, Carter JR. Degenerative disk disease: assessment of changes in vertebral body marrow with MR imaging. Radiology 1988; 166(1 Pt 1): 193–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, Hodler J, Boos N. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001; 26: 1873–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjorck-van Dijken C, Fjellman-Wiklund A, Hildingsson C. Low back pain, lifestyle factors and physical activity: a population based-study. J Rehabil Med 2008; 40: 864–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwab F, Lafage V, Patel A, Farcy JP. Sagittal plane considerations and the pelvis in the adult patient. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009; 34: 1828–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a13c08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan Q, Lin C, Li X, Zeng W, Ma C. MRI assessment of paraspinal muscles in patients with acute and chronic unilateral low back pain. Br J Radiol 2015; 88: 20140546. doi: https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20140546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D'Hooge R, Cagnie B, Crombez G, Vanderstraeten G, Dolphens M, Danneels L. Increased intramuscular fatty infiltration without differences in lumbar muscle cross-sectional area during remission of unilateral recurrent low back pain. Man Ther 2012; 17: 584–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2012.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi K, Miyazaki T, Takino T, Matsui T, Tomita K. Epidural pressure measurements. Relationship between epidural pressure and posture in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995; 20: 650–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suzuki H, Endo K, Kobayashi H, Tanaka H, Yamamoto K. Total sagittal spinal alignment in patients with lumbar canal stenosis accompanied by intermittent claudication. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010; 35: E344–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c91121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krssak M, Petersen KF, Bergeron R, Price T, Laurent D, Rothman DL, et al. Intramuscular glycogen and intramyocellular lipid utilization during prolonged exercise and recovery in man: a 13C and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 748–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White LJ, Ferguson MA, McCoy SC, Kim H. Intramyocellular lipid changes in men and women during aerobic exercise: a (1)H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 5638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White LJ, Robergs RA, Sibbitt WL, Jr, Ferguson MA, McCoy S, Brooks WM. Effects of intermittent cycle exercise on intramyocellular lipid use and recovery. Lipids 2003; 38: 9–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11745-003-1024-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haefeli M, Kalberer F, Saegesser D, Nerlich AG, Boos N, Paesold G. The course of macroscopic degeneration in the human lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006; 31: 1522–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000222032.52336.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chrischilles EA, Butler CD, Davis CS, Wallace RB. A model of lifetime osteoporosis impact. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151: 2026–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernard CP, Liney GP, Manton DJ, Turnbull LW, Langton CM. Comparison of fat quantification methods: a phantom study at 3.0T. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 27: 192–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.21201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB. Quantitative assessment of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 34: 729–49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hebert JJ, Kjaer P, Fritz JM, Walker BF. The relationship of lumbar multifidus muscle morphology to previous, current, and future low back pain: a 9-year population-based prospective cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014; 39: 1417–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tabaraee E, Ahn J, Bohl DD, Phillips FM, Singh K. Quantification of multifidus atrophy and fatty infiltration following a minimally invasive microdiscectomy. Int J Spine Surg 2015; 9: 25. doi: https://doi.org/10.14444/2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang Q, Zhang Y, Li D, Yang D, Huo M, Maruyama H. The evaluation of chronic low back pain by determining the ratio of the lumbar multifidus muscle cross-sectional areas of the unaffected and affected sides. J Phys Ther Sci 2014; 26: 1613–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGill SM. A revised anatomical model of the abdominal musculature for torso flexion efforts. J Biomech 1996; 29: 973–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boesch C, Decombaz J, Slotboom J, Kreis R. Observation of intramyocellular lipids by means of 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Proc Nutr Soc 1999; 58: 841–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]