Abstract

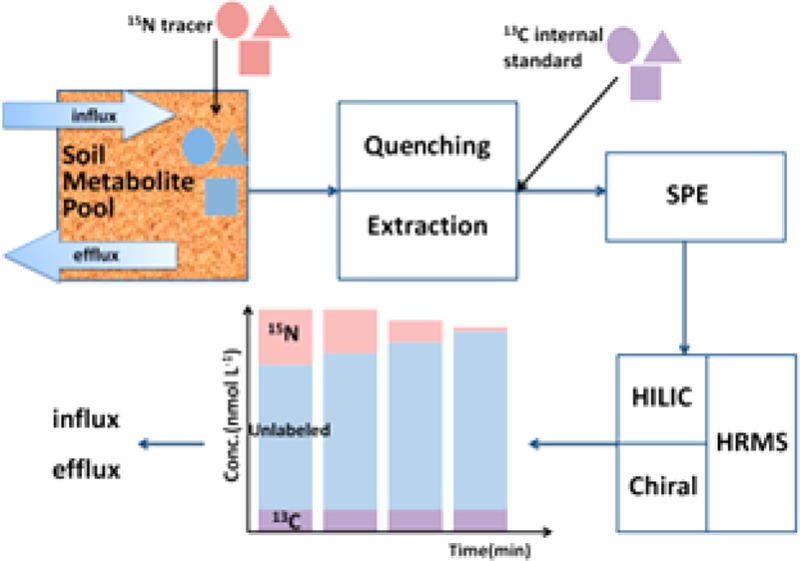

Soil fluxomics analysis can provide pivotal information for understanding soil biochemical pathways and their regulation, but direct measurement methods are rare. Here, we describe an approach to measure soil extracellular metabolite (amino sugar and amino acid) concentrations and fluxes based on a 15N isotope pool dilution technique via liquid chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry. We produced commercially unavailable 15N and 13C labeled amino sugars and amino acids by hydrolyzing peptidoglycan isolated from isotopically labeled bacterial biomass and used them as tracers (15N) and internal standards (13C). High-resolution (Orbitrap Exactive) MS with a resolution of 50 000 allowed us to separate different stable isotope labeled analogues across a large range of metabolites. The utilization of 13C internal standards greatly improved the accuracy and reliability of absolute quantification. We successfully applied this method to two types of soils and quantified the extracellular gross fluxes of 2 amino sugars, 18 amino acids, and 4 amino acid enantiomers. Compared to the influx and efflux rates of most amino acids, similar ones were found for glucosamine, indicating that this amino sugar is released through peptidoglycan and chitin decomposition and serves as an important nitrogen source for soil microorganisms. d-Alanine and d-glutamic acid derived from peptidoglycan decomposition exhibited similar turnover rates as their l-enantiomers. This novel approach offers new strategies to advance our understanding of the production and transformation pathways of soil organic N metabolites, including the unknown contributions of peptidoglycan and chitin decomposition to soil organic N cycling.

Metabolomics is an emerging field that studies small-molecule metabolites in biological systems and has opened up a new way to help reveal biochemical links between microbial community structure and metabolic function in ecosystems.1 Metabolites containing a primary amine group (e.g., amino sugars and amino acids) are crucial in microbial metabolism because they are one of the major N sources for soil microorganisms and simultaneously can be used as a C source under C limiting conditions.2 Amino sugars bound in polymers generally account for 5–8% of soil total nitrogen (TN), whereas bound amino acids contribute approximately 30–60% of TN.3,4 Moreover, amino sugars (glucosamine and muramic acid), d-alanine, d-glutamic acid, and meso-diaminopimelic acid (mDAP) are biomarkers specific for bacterial and/or fungal cell walls.5−7 These metabolites are almost exclusively present in the form of high molecular weight (HMW) polymers, i.e., peptidoglycan, chitin, and protein in soils,8 which can be utilized by microorganisms only after being depolymerized by extracellular hydrolytic enzymes to yield small oligomers or monomers.9 Recent research showed that it is this depolymerization step that is the major bottleneck of terrestrial N cycling.10−12 The free pool of amino acids is very small and contributes to less than 1% of the total pool,13 but it is highly dynamic with mean residence times in the range of minutes to a few hours.9,14 While some advances have been made regarding concentrations and fluxes of free amino acids in soils, very little is known about the respective dynamics and pool sizes of free amino sugars and d-amino acids in soils.14−16 Unlike metabolite concentrations that give only a static snapshot of the physiological state, quantification of rapid metabolic fluxes provides critical information on the rates and controls of microbial processes in soils and on the pathways of production and microbial utilization. Thus, there is an urgent need for a comprehensive analytical method to quantify the pool sizes and in situ fluxes of these metabolites in soil.

Stable isotopes have become an indispensable tool in metabolomics and fluxomics research, where they are used as tracers or as internal standards (IS).17 In soils, flux analyses based on stable isotope analysis are rarer and have been used mainly to study the metabolism, respiration, or incorporation of position or fully labeled organic compounds.18,19 More recently, stable isotope techniques have been developed to measure gross fluxes of organic compounds in soils, based on isotope pool dilution theory.9,20 For instance, gross production caused by depolymerization of glucans and proteins and concomitant microbial consumption of glucose and amino acids have been investigated in soil by isotope pool dilution approaches using 13C labeled glucose and a mix of 15N labeled amino acids as tracers.9,21 Additionally, stable isotope labeled (SIL) analogues have nearly identical chemical and physical properties as those of the target analytes; SIL compounds are therefore often used as ISs in relative and absolute quantification in order to minimize matrix effects and to correct compound losses during sample preparation.22,23 However, access to SIL standards is limited for some metabolites due to commercial unavailability (e.g., muramic acid, mDAP, N-acetylglucosamine) or prohibitively high costs (e.g., d-alanine). An alternative strategy to overcome these problems is to obtain SIL metabolites through biological in vivo synthesis. In a number of studies, fully SIL metabolites were extracted from microorganisms grown in isotopically labeled substrates (e.g., 13C glucose), which were used as ISs for a large number of intracellular metabolites.24

Chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry is extensively employed for metabolite identification and quantification as it can provide information on retention time, molecular mass, and compound structure. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) has been successfully applied for quantifying amino acids and amino sugars, but different off-line derivatization procedures are necessary for distinct compounds as they are nonvolatile; these procedures are time-consuming and involve uncertainty in the derivatization reaction.3,9,25 Capillary electrophoresis/mass spectrometry (CE/MS) provides an approach for underivatized analysis of organic N compounds, but ionization suppression caused by ion-pairing agents and migration time fluctuations narrow its application in metabolite quantification.26 Recently, hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) has drawn increasing attention since it offers enhanced retention and separation for hydrophilic substances such as amino sugars, amino acids, sugars, and nucleotides compared to that of reversed phase chromatography.27 Although its applications in soil metabolomics remain limited due to the high amount of coextracted interfering substances from soils, HILIC demonstrates satisfactory performance in separating hydrophilic substances from the sample matrix.26,28 Compared to unit mass resolution MS such as quadrupole MS, the high resolution, mass accuracy, and sensitivity of Orbitrap-MS instruments have led to their increasing application in SIL-assisted metabolic studies.29 The high mass resolution (50 000 to 200 000) of Orbitrap-MS greatly improves its specificity, enables elemental formula derivation, and makes it feasible to distinguish different isotopologues (i.e., m/z + 1 of 15N versus 13C labeled metabolite with a Δmass of 0.0063 Da), which is critical in multi-isotope tracing metabolomics studies.30 The mass accuracy of Orbitrap-MS is better than 3 ppm, thereby allowing putative metabolite identification via element composition and isotope patterns in a complex matrix, even without information on its product ions.31 On the basis of these advantages, HR full-scan MS has been proven to generate reliable quantitative data in high-throughput metabolomics studies.30

The main purpose of this work was to develop a robust, comprehensive, and high-throughput method to quantitatively measure extracellular fluxes of amino acid enantiomers and amino sugars in soils, based on the isotope pool dilution technique, via an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and high-resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC/HRMS) platform. In this study, methods of reaction quenching, extraction efficiency, and purification/desalting of free soil amino acids and amino sugars were developed and evaluated. The range of necessary SIL metabolites was produced through acid hydrolysis of peptidoglycan purified from bacteria cultivated in uniformly isotopically labeled growth medium, where 15N labeled ones were used as tracers for fluxes and 13C labeled ones as ISs. All key amino acid and amino sugar metabolites in soils and their isotope labeled analogues were successfully identified and quantified via the developed UPLC/HRMS platform. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of LC/HRMS in soil fluxomics and for absolute quantification of these free metabolite classes in soil.

Experimental Section

Chemicals and Materials

15N and 13C (98 atom %+) celtone base powder, 15N and 13C (98 atom %+) spectra 9, and 15N (98 atom %) and 13C (97–99 atom %) algal amino acid mixture were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA). 15N and 13C enriched microbial growth media were prepared by dissolving 0.5 g of celtone base powder in 500 mL of spectra 9. All unlabeled metabolite standards and trypsin from the bovine pancreas (lyophilized powder, 1000–2000 BAEE units/mg solid) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). LC/MS grade solvents and chemicals were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Bremen, Germany). Soil samples (0–15 cm depth) were collected from a long-term cultivated arable field and an adjacent mixed deciduous-conifer forest in Trautenfels (Styria, Austria) in June 2016. Further details on the sample processing and soil properties can be found in Supporting Information (Table S1).

Uniformly 15N and 13C Labeled Amine Metabolite Purification

Peptidoglycan is a polymer of amino sugar strands (N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid) cross-linked via short peptides (d- and l-alanine, d-glutamic acid, mDAP, l-glycine, and variants thereof). Thus, commercially unavailable SIL metabolites were obtained by acid hydrolysis of purified peptidoglycan. Bacillus subtilis (DMDZ 10) was cultivated in uniformly 15N or 13C labeled medium overnight at 37 °C. The peptidoglycan was extracted using a previously described method with some modification (Table S2).32 Approximately 1 mg of raw peptidoglycan was hydrolyzed in 10 mL of 6 M HCl (12 h, 110 °C). In order to remove HCl, hydrolysates were dried under a gentle N2 flow and redissolved in water. Finally, the uniformly 15N or 13C labeled metabolites were lyophilized and stored at −20 °C. Prior to the metabolic flux experiment, these 15N and 13C labeled metabolites were dissolved in water and analyzed by LC/MS for purity and concentration (Table S3).

Instrumentation

Sample analyses were performed on an UPLC 3000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) coupled to an Orbitrap Exactive MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The Orbitrap system was calibrated daily for ESI positive mode with Pierce LTQ ESI positive calibration solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). The MS was operated under full-mass scan mode (m/z 50–600) using ESI positive mode, and automatic gain control (AGC) target values were set to 1 × 106. The resolution was set to 50 000 to allow separation of 15N and 13C labeled isotopologues. “Lock mass” correction was set to 105.04232 (sodium adduct of acetonitrile dimer) and 214.08963 (protonated N-butylbenzenesulfonamide, a common contaminant from plasticizer). The other parameters of the MS instrument were as follows: spray voltage, 3.5 kV; capillary temperature, 300 °C; sheath gas, 35 arbitrary units; and aux gas, 15 arbitrary units.

Amino acids and amino sugars were separated using an Accucore HILIC column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm particle size) with a preparative guard column (10 mm × 2.1 mm, 3 μm particle size; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Separation was performed with eluent A (water, 0.1% v/v formic acid) and eluent B (acetonitrile (ACN), 0.1% v/v formic acid) according to the following gradient: 0 min, 5% A; 2 min, 5% A; 19 min, 40% A; 24 min, 40% A; 27 min, 5% A; and 45 min, 5% A. Amino acid enantiomers were analyzed by an Astec chirobiotic T column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm particle size) with a preparative guard column (10 mm × 2.1 mm, 3 μm particle size; Sigma-Aldrich, Vienna, Austria). The separation was performed by isocratic elution with 80/20/0.1 (v/v) methanol/water/formic acid. The injection volume for both methods was set to 25 μL. The column was thermostated at 25 °C, and eluent flow rates were 0.3 mL min–1.

Analytical Performance of the UPLC/HRMS Platform

Stock solutions of individual unlabeled metabolites were prepared at 20 mM and mixed to give a combined standard (0.5 mM per analyte). The 15N labeled compound mixture was prepared by dissolving 15N-peptidoglycan hydrolysate and 15N algal amino acid mixture, resulting in a final concentration of approximately 10 μM of each analyte. The 13C labeled IS was prepared with the corresponding 13C labeled compounds, resulting in a final concentration of approximately 20 μM of each analyte. All stock solutions, 15N tracer mixes, and 13C-IS were prepared in LC/MS-grade water.

The unlabeled metabolite mixture was subject to a serial dilution; final concentrations of calibration standards ranging from 1 nM to 25 μM. These standards were subsequently injected in the LC/MS system to evaluate the retention time, linear range, and limit of quantification (LOQ) of each metabolite. LOQ was defined as the lowest concentration with a signal-to-noise ratio of 10. Mass-to-charge (m/z) accuracy was calculated based on the relative difference of the observed m/z and theoretical m/z. Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by spiking a 15N labeled tracer mix to a purified soil extract. The QC samples were then used to determine relative standard deviation (RSD) of interday and intraday measurements of concentration and isotope ratios. All calibration standards and QC samples were spiked with 50 μL of 13C labeled IS at a 1:9 ratio (IS/sample) before LC/MS analysis. Isotope calibrations of the system were performed with different 15N enrichments (natural abundance, 5, 10, 25, and 50 atom % 15N) at four concentrations (0.2, 2, 10, and 20 μM) for 15 amino compounds and analyzed by multiple regression analysis (Table S4).

Extracellular N Metabolite Extraction and Purification

If not specified, extraction of soil amino acids and amino sugars was carried out by adding cold (4 °C) 1 M potassium chloride (KCl) to soil samples and subsequently shaking on an orbital shaker for 30 min (4 °C, 200 rpm). Thereafter, extracts were filtered through ash-free cellulose filters and 50 μL of 13C-IS was spiked to 10 mL of filtered extract, followed by freezing with liquid nitrogen immediately. The frozen soil extracts were then lyophilized for 48 h and redissolved with 10 mL of methanol. Insoluble salts were discarded by centrifugation at 12 000g for 5 min. Supernatants were evaporated to dryness under a stream of N2 and redissolved in 2 mL of 0.01 M HCl. Cation-exchange solid phase extraction (SPE) cartridges were prepared by packing 4 g of Dowex 50WX8 resin (100–200 mesh, H+ form, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 6 mL polypropylene tubes and rinsing sequentially with 12 mL of water, 1 M HCl, and 0.1 M HCl each and finally with 36 mL of water. After samples were loaded on the resin, the resin was washed with 10 mL of water, and then analytes were slowly eluted with 10 mL of 3 M NH4OH over 30 min. Eluates were dried under a gentle N2 flow, and dried residues were redissolved in 500 μL of ACN/H2O (80/20, v/v) for further analysis by LC/MS.

Metabolite Spike Recovery

A spike recovery experiment was carried out to calculate the recovery rate of the overall sample preparation and to evaluate the effectiveness of using 13C metabolites as IS to correct for total uncertainty in sample preparation and LC/MS analysis. Aliquots of 4 g of arable soil were sterilized in plastic containers by autoclaving at 125 °C for 25 min and then mixed with 500 μL of 15N labeled tracer solution. After being incubated for 30 min, all soil samples were extracted as described before. Samples were then divided into three groups, which were IS before purification, IS postpurification, and no IS. In IS before purification samples, 50 μL of 13C IS was spiked before freeze drying the KCl extracts and then purified as described above. In IS postpurification, samples were spiked with 50 μL of 13C IS after cation-exchange SPE. In no IS samples, 50 μL of water was added to the extract before freeze drying. All samples from the three groups were then analyzed by LC/Orbitrap-MS to calculate the recovery rates of 15N labeled tracer.

Metabolic Flux Analysis

An isotope pool dilution (IPD) assay was developed to quantify the gross extracellular fluxes of amino sugars and amino acids (enantiomers) in soil, in which the target pool was labeled by adding 15N labeled tracers. By tracking the pool size and the ratio of tracer (15N labeled metabolite) and tracee (unlabeled metabolite), gross influx (which is caused mainly by the depolymerization of HMW organic N) and gross efflux rates (i.e., uptake by soil microorganisms) of each metabolite can be calculated. Added 15N metabolites comprised less than 30% of the original target metabolite pool size, based on preliminary determination shortly before each tracer experiment, except for a few compounds such as muramic acid. Prior to the experiment, soil samples were preincubated at the same temperature (15 °C) and moisture level (60% of water-holding capacity) for 24 h. Then, aliquots of 4 g of soil were weighed into 50 mL polypropylene centrifuge tubes in triplicates per soil type and per time point of sampling. Next, 500 μL of 15N labeled metabolite mix was added to each soil sample and homogenized by vigorous shaking by hand. The incubation was quenched by adding 20 mL of cold (4 °C) 1 M KCl at 15 min, 40 min, 60 min, 90 min, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, and 5 h. Extraction, cleanup, and analysis via LC/MS were then performed as described in the previous section.

Quenching Efficiency

The quenching experiment was designed to assess the influence of extraction temperature on the inhibition of depolymerization and microbial uptake during the extraction step. For this, the arable soil was used since it showed the most rapid fluxes according to prior tests. Briefly, 500 μL of 15N labeled tracer mix was added to replicate samples of 4 g of arable soil at 15 °C for 30 min. The extraction and filtration steps were performed at three different temperatures (25, 15, and 4 °C), with the extractant being equilibrated to the respective temperatures beforehand. After extraction, the soil suspensions were left standing at the respective temperatures for 30, 60, and 90 min before filtration to investigate whether influx and efflux of amino compounds were inhibited in the soil suspension. Cleanup and analysis via LC/MS were conducted as stated above.

Gross Flux Calculations

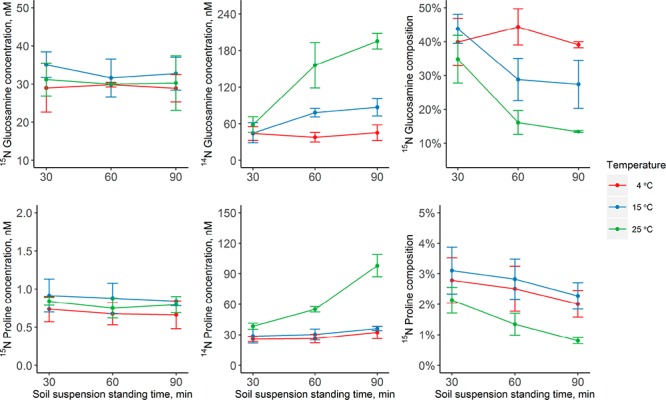

Rates of gross influx (GI) and gross efflux (GE) of each metabolite (μg N g–1 d.w. d–1) were calculated based on IPD theory33 as follows

|

where C(15N) and C(14N) are the concentrations of 15N labeled and unlabeled metabolites (μg N g–1 d.w.), respectively, C(tot) is the sum of them, and at % 15N represents atom % 15N. At % 15Nb represents the natural abundance of 15N. t1 and t2 represent the quenching times (min), which were 15 and 60 min for most metabolites except for muramic acid, where quenching times of 15 and 240 min were used due to slower turnover rates.

Results and Discussion

Purity and Labeling Efficiency of Uniformly 15N and 13C Labeled Amino Compounds

A variety of SIL metabolites can be obtained via in vivo biosynthesis, which is often plagued with problems of low purity and complex matrix. In our approach, a large fraction of amino compounds were obtained from purified and acid hydrolyzed peptidoglycan, as it is a polymer of amino sugars and d- and l-amino acids and is relatively easy to purify. The chemical composition of peptidoglycan varies significantly among bacteria; for instance, the bacterial taxonomic biomarker, i.e., mDAP, exists mainly in most Gram-negative (e.g., Escherichia coli) and some Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., B. subtilis). Considering that the content of peptidoglycan in Gram-positive bacteria is 5–10 times higher than in Gram-negative bacteria, B. subtilis was selected as the source of peptidoglycan. Specifically, its peptidoglycan consists of N-acetylglucosamine, N-acetylmuramic acid, d-glutamate, mDAP, l-alanine, d-alanine, and l-glycine.34 The purity of the obtained metabolites was consequently checked since some insoluble cell wall proteins might have remained as impurities with the raw peptidoglycan after hot SDS extraction and trypsin digestion. As protein impurities are decomposed to amino acids atypical to peptidoglycan during acid hydrolysis, the amount of impurities can be calculated by quantifying the amino acids that do not derive from peptidoglycan. A low content (<6%) of residual protein was found in the isolated and hydrolyzed peptidoglycan (Table S2), which indicates the high purity of our peptidoglycan preparation. However, the protein impurities would not have impaired the quality of the isotopically labeled tracer because the tracer used in the flux assays was a mixture of labeled peptidoglycan hydrolysates and labeled algal amino acids and its concentration was quantified before the experiments (Table S3).

In order to obtain commercially unavailable SIL metabolites from fully SIL bacterial cells, media fully labeled (>98 at %) with 15N or 13C in all nitrogen or carbon sources were used for B. subtilis cultivation. The use of celtone base powder and spectra 9 as the growth medium not only ensures isotope enrichment in all main carbon or nitrogen sources (carbohydrates, amino acids) but also isotopically enriches other less abundant essential nutrients (e.g., vitamins), which minimizes eventual contamination of 14N and 12C in the target metabolites. Additionally, these media are relatively cheap and do not need extra labor or knowledge for preparing culture media. The level of isotope enrichment of each metabolite in the 15N tracer mix and the 13C labeled IS was calculated as the contribution of its fully labeled form to labeled and nonlabeled forms. High (>95%) extents of isotope enrichment were found in all metabolites derived from peptidoglycan (Table S2). In summary, by isolating peptidoglycan from fully isotopically labeled bacterial biomass, we provide a fast and cost-effective approach via biosynthesis of high-purity commercially unavailable amino sugars (muramic acid) and amino acids (mDAP) and a cheaper source for those metabolites that come at high costs (e.g., d-alanine, d-glutamic acid).

UPLC/HRMS Method Validation

The retention time and its stability, mass accuracy, LOQ, linear range, and quantitative reproducibility (RSD) of standard compounds and their SIL analogues are listed in Table 1. Apart from amino acid enantiomers, all 22 standard compounds were successfully separated by HILIC in a 45 min run, with the compounds eluting between 6 and 13 min. Amino acid enantiomers were separated on a chiral column by isocratic elution over 11 min. For HILIC separations, it is recommended to use slow gradients and lengthy re-equilibration times (18 min in this case) to provide robust and reproducible results, as the equilibration time between changing the eluent composition and the stationary phase is relatively slow.3515N and 13C labeled metabolites showed nearly identical retention times compared to those of unlabeled standards (RSD < 1.7%), and retention time stability was excellent with RSD < 3%. Most chromatographic peaks had a width of ∼40 s, with the exceptions of aspartic acid and mDAP, which were slightly tailing (peak width of 120 s) (Figure S1). It is noteworthy that the isomers of glucosamine (i.e., mannosamine, galactosamine) and leucine (i.e., isoleucine) could not be resolved as they have identical molecular masses and very similar chromatographic behavior in HILIC. However, in soils, free hexosamines other than glucosamine represent only a minor fraction or are below LOD.3

Table 1. Retention Time, Detected Mass, Mass Accuracy, LOQ, Calibration Range, Determination Coefficient, Relative Standard Deviation (RSD), and Recovery of 22 Amino Compounds Separated by HILIC or Chiral Columns and Measured by Orbitrap Exactive-MS.

| RSD (%) |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| metabolite | neutral formula | retention time (min) | retention time RSD (%) | detected unlabeled mass [M + H]+ | mass error (ppm) | detected 15N mass [15N – M + H]+ | mass error (ppm) | detected 13C mass [13C – M + H]+ | mass error (ppm) | LOQ (nM) | calibration range (μM) | determination coefficient (R2) | intraday | interday | recovery of no IS (%) | recovery of IS spike after purification (%) | recovery of IS spike before purification (%) |

| HILIC Separation | |||||||||||||||||

| glucosamine | C6H13NO5 | 8.76 | 0.5 | 180.08636 | –1.6 | 181.08340 | –1.6 | 186.10651 | –1.4 | 75 | 0.1–15 | 0.9993 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 26 ± 14 | 74 ± 3 | 81 ± 9 |

| muramic acid | C9H17NO7 | 8.04 | 0.5 | 252.10725 | –2.1 | 253.10422 | –2.4 | 261.13742 | –2.1 | 5 | 0.005–10 | 0.9997 | 5.1 | 6.7 | 18 ± 12 | 57 ± 1 | 99 ± 6 |

| mDAP | C7H14N2O4 | 12.94 | 0.3 | 191.10233 | –1.6 | 193.09650 | –1.1 | 198.12582 | –1.5 | 20 | 0.1–15 | 0.9996 | 4.4 | 3.4 | 21 ± 1 | 49 ± 5 | 102 ± 9 |

| alanine | C3H7NO2 | 8.48 | 3.1 | 90.05533 | 4.2 | 91.05241 | 4.6 | 93.06541 | 4.4 | 10 | 0.05–10 | 0.9987 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 28 ± 20 | 66 ± 25 | 105 ± 1 |

| glutamic acid | C5H9NO4 | 8.29 | 2.0 | 148.06026 | –1.2 | 149.05740 | –0.5 | 153.07712 | –0.4 | 20 | 0.075–15 | 0.9998 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3 ± 2 | 24 ± 1 | 65 ± 32 |

| glycine | C2H5NO2 | 8.92 | 2.6 | 76.03976 | 6.0 | 77.03681 | 6.1 | 78.04647 | 6.0 | 15 | 0.02–10 | 0.9997 | 0.4 | 3.8 | 21 ± 3 | 81 ± 15 | 86 ± 5 |

| lysine | C6H14N2O2 | 12.42 | 1.1 | 147.11259 | –1.5 | 149.10674 | –0.9 | 153.13275 | –1.0 | 50 | 0.1–15 | 0.9993 | 0.9 | 9.9 | 25 ± 1 | 27 ± 3 | 71 ± 3 |

| valine | C5H11NO2 | 7.80 | 3.0 | 118.08643 | 1.5 | 119.08345 | 1.3 | 123.10310 | 0.8 | 20 | 0.05–1 | 0.9972 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 74 ± 18 | 81 ± 57 | 108 ± 1 |

| leucine | C6H13NO2 | 7.40 | 2.2 | 132.10185 | –0.4 | 133.09889 | –0.4 | 138.12193 | –0.5 | 5 | 0.075–10 | 0.9994 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 28 ± 11 | 78 ± 13 | 91 ± 5 |

| methionine | C5H11NO2S | 7.84 | 2.1 | 150.05817 | –1.0 | 151.05518 | –1.2 | 155.07491 | –1.1 | 5 | 0.05–2 | 0.9971 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 63 ± 51 | 82 ± 65 | 73 ± 28 |

| phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | 7.54 | 2.6 | 166.08611 | –0.9 | 167.08313 | –1.0 | 175.11626 | –0.8 | 1 | 0.02–5 | 0.9955 | 0.4 | 4.2 | 65 ± 45 | 65 ± 40 | 79 ± 20 |

| proline | C5H9NO2 | 9.68 | 1.2 | 116.07069 | 0.7 | 117.06779 | 1.3 | 121.08749 | 1.1 | 5 | 0.05–10 | 0.9997 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 26 ± 1 | 53 ± 4 | 84 ± 0 |

| serine | C3H7NO3 | 9.16 | 1.1 | 106.05003 | 1.5 | 107.04716 | 2.4 | 109.06017 | 2.3 | 750 | 1–15 | 0.9997 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 15 ± 2 | 82 ± 13 | 86 ± 1 |

| threonine | C4H9NO3 | 9.02 | 1.3 | 120.06558 | 0.5 | 121.06268 | 1.0 | 124.07902 | 0.8 | 10 | 0.02–10 | 0.9998 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 13 ± 4 | 88 ± 3 | 89 ± 2 |

| tyrosine | C9H11NO3 | 7.55 | 2.6 | 182.08095 | –1.2 | 183.07799 | –1.2 | 191.11104 | –1.5 | 1 | 0.025–5 | 0.9963 | 3.5 | 7.3 | 25 ± 17 | 74 ± 3 | 75 ± 7 |

| asparagine | C4H8N2O3 | 9.82 | 1.2 | 133.06067 | –0.7 | 135.05473 | –0.7 | 137.07405 | –1.0 | 20 | 0.02–7.5 | 0.9998 | 4.8 | 13.7 | 0 ± 0 | 61 ± 58 | 81 ± 10 |

| aspartic acid | C4H7NO4 | 8.73 | 0.9 | 134.04466 | –0.9 | 135.04172 | –0.7 | 138.05804 | –1.1 | 10 | 0.02–10 | 0.9995 | 2.3 | 4.3 | 2 ± 0 | 18 ± 0 | 88 ± 1 |

| glutamine | C5H10N2O3 | 9.83 | 0.7 | 147.07625 | –1.1 | 149.07034 | –1.0 | 152.09300 | –1.1 | 5 | 0.02–7.5 | 0.9998 | 2.8 | 16.7 | 2 ± 8 | 21 ± 3 | 48 ± 13 |

| arginine | C6H14N4O2 | 11.97 | 0.9 | 175.11873 | –1.3 | 179.10687 | –1.2 | 181.13882 | –1.3 | 25 | 0.05–10 | 0.9993 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 14 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 | 74 ± 3 |

| histidine | C6H9N3O2 | 12.25 | 0.9 | 156.07660 | –1.0 | 159.06767 | –1.2 | 162.09663 | –1.4 | 20 | 0.05–10 | 0.9999 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 35 ± 2 | 66 ± 2 | 87 ± 1 |

| Chiral Separation | |||||||||||||||||

| l-alaninea | C3H7NO2 | 3.07 | 1.3 | 90.05531 | 3.9 | 91.05239 | 4.4 | 93.06545 | 4.8 | 10 | 0.1–10 | 0.9999 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 27 ± 6 | 73 ± 13 | 107 ± 4 |

| d-alaninea | C3H7NO2 | 4.12 | 0.6 | 90.05532 | 4.1 | 91.05239 | 4.4 | 93.06546 | 4.9 | 10 | 0.1–10 | 0.9993 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 18 ± 3 | 53 ± 21 | 94 ± 20 |

| l-glutamic acida | C5H9NO4 | 2.77 | 1.3 | 148.06046 | 0.2 | 149.05763 | 1.1 | 153.07720 | 0.1 | 50 | 0.1–5 | 0.9993 | 0.7 | 2.5 | 11 ± 1 | 41 ± 13 | 83 ± 24 |

| d-glutamic acida | C5H9NO4 | 3.38 | 1.4 | 148.06045 | 0.1 | 149.05756 | 0.6 | 153.07722 | 0.2 | 50 | 0.1–5 | 0.9990 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 13 ± 5 | 37 ± 9 | 75 ± 18 |

The data were measured on Astec chirobiotic T colum.

High-resolution accurate mass (HR) full-scan analysis with Orbitrap-MS has been proven to provide adequate specificity for quantitative, targeted analysis in complex matrices, comparable to that of multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) analysis performed by triple quadrupole MS.36 It also requires much less labor for method development, which is important for large-scale metabolic analysis. The Orbitrap Exactive instrument can be maximized in terms of resolving power and mass accuracy by operating at a resolution of 100 000 and an AGC target value of 5 × 105, but this will lead to a decline in scan speed and loss of dynamic range. As we were performing targeted, quantitative analysis of metabolites across a large range of concentrations in soil, the objective here was to ensure the absence of peak overlap of target metabolites and to maximize the linear range. Separation of 13C- and 15N-SIL analogues (isotopologues) with similar masses can be achieved with a mass resolution of 50 000 and using lock mass correction. For instance, 13C1-glycine and 15N-glycine with a m/z difference of 0.0063 can be resolved easily (Figure S2). Therefore, the AGC target was set to its maximum value (3 × 106) to expand the linear range. Except for alanine (average mass error of 4.4 ppm) and glycine (6.0 ppm), the mass accuracy of all other compounds and their SIL analogues was high, with the mass error being <1.5 ppm with a median of −0.5 ppm (Table 1), which is sufficient for the identification of target metabolites.

In general, the analytical performance of alanine and glutamic acid enantiomers on both Chirobiotic and HILIC columns was very similar. Calibration curves were constructed by plotting the ratios of the response of the target compound to the internal standard versus the theoretical concentrations. Good linearity of MS response (R2 > 0.9955) was observed for all compounds with a linear dynamic range of 2 and 4 orders of magnitude, which was similar to that in previous publications.9,26 The dynamic range was, however, expected to be larger, but it was restricted here as the maximum concentrations of standards analyzed were about 10 μM. The lowest dynamic range was found for serine, the compound with highest LOQ. Most metabolites had LOQs ranging from 1 to 75 nM with an average of 13 nM, whereas serine obviously showed the highest LOQ (750 nM). Our method provided similar or better sensitivity for most amino compounds, as they showed lower LOQ in comparison to that of other LC/MS2 or GC/MS methods.9,37 QC samples were used to determine the intraday and interday precision (RSD), which ranged from 0.1 to 5.1% and 0.7 to 16.7% respectively. The largest intraday variance (RSD) was found for lysine, glutamine, and asparagine.

Evaluation of the Sample Preparation Procedure and Recovery Rate

Metabolites in soil normally are present at levels of ng g–1 to μg g–1; therefore, efficient extraction, preconcentration, and cleanup are crucial steps in sample preparation. Using 1 M KCl as the extractant provided the highest extraction yields of amino sugars and amino acids compared to those using other common extraction media (i.e., water, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.5 M K2SO4, 0.5 M KCl),38 but high concentrations of salts in soil extracts cause strong ion suppression in the ESI ion source of the Orbitrap-MS. It has been reported that after 10-fold concentrating, even in soil water extracts, the MS signal of some organic analytes is completely lost due to coelution of salts.26 Therefore, the aim of the purification procedure here was to efficiently remove inorganic salts from the extracts while maximizing the recovery of the target metabolites. Methanol is a weak polar solvent exhibiting much lower salt solubility than water while providing efficient dissolution of most polar compounds.39,40 SPE clearly offers better selectivity and recovery of target analytes by manipulating the pH and ion strength of the eluent, but it has disadvantages in terms of capacity and complexity of handling. Considering handling time and extraction efficiency, methanol extraction and cation-exchange SPE were applied sequentially for removing the majority (methanol dissolution) and residual of unwanted salts (SPE). The SPE procedure was optimized by testing the purification performance of different resins and commercial SPE cartridges. Dowex 50WX8 resin demonstrated the highest recovery for most amino compounds (Figure S3). The final sample treatment protocol with freeze drying, methanol dissolution, and cation-exchange chromatography allowed for a 20-fold enrichment in concentration (from 10 mL to 500 μL) while decreasing salt loads by >105-fold.

Recoveries of spiked 15N tracers in IS before purification, IS postpurification, and no IS samples are shown in Table 1. Compared with recoveries of IS postpurification, several compounds from no IS showed significantly lower recoveries, which strongly suggests that ion suppression occurred for those metabolites in the ESI source. Recovery rates of the overall purification method can be obtained from the IS postpurification samples, as the 13C-IS corrects only for matrix effects but not for metabolite losses during purification. The data show large differences in the recoveries among various compounds, ranging from 18 to 88% (with an average recovery of 59%), which resulted from their different behavior during the purification procedure. Large variation in recoveries was observed for glutamic acid, methionine, asparagine, and phenylalanine. However, in samples where IS was added before purification, the overall mean recovery increased to 84% and became much less variable, with less than 13% standard deviation in most metabolites. The addition of 13C-IS provided a great improvement by compensating for matrix effects and losses during sample preparation. In previous research, due to limited access to SIL analogues, it was rarely possible to add SIL-IS for all substances. A common approach therefore is to divide analytes into several groups based on similarities in physical and chemical properties, and individual IS are then applied for each group.37 However, our data strongly indicate that metabolites with similar characteristics (e.g., asparagine and glutamine) did not perform comparably in terms of recovery rates. Utilization of insufficient numbers of IS can therefore lead to rising errors and uncertainty of the data. The addition of the full complement of 13C labeled IS for the target analytes is strongly recommended to effectively overcome the matrix effects and to correct for losses during sample preparation, and concurrently, IS addition greatly enhanced the robustness, accuracy, and precision of quantitative analysis.

Quenching Efficiency

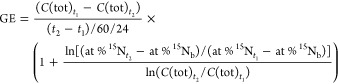

Fluxomics research requires reproducible and reliable quenching and extraction methods. A suitable quenching method for IPD assays should fulfill the following criteria: (i) inhibit extracellular enzymatic activity and microbial consumption while (ii) allowing efficient extraction of the extracellular target metabolites. A previous approach to measure the release and consumption of free amino acids in litter applied extraction with 10 mM CaSO4 with 3.7% formaldehyde, the latter effectively inhibiting extracellular enzyme activity and curtailing microbial uptake of amino acids while causing deamidation of Gln and Asn to Glu and Asp.9 Although CaSO4 allows high extraction yields of extracellular metabolites in litter, it is unsuitable for soils due to low extraction efficiency. We therefore sought alternative quenching protocols using low-temperature extraction with 1 M KCl. Here, we show the behaviors of glucosamine and proline as examples to evaluate the influence of extraction temperature on the quenching efficiency. The concentration of the 15N tracer was used to investigate whether microbial metabolite consumption was sufficiently stopped. Figure 1 demonstrates that even at 25 °C both the 15N-glucosamine and 15N-proline concentrations did not decrease significantly over time, indicating that the high concentration of KCl and the dilution effect was sufficient to inhibit the uptake of these metabolites by microbial organisms. In addition, extraction efficiency was similar across different temperatures. As the extracellular metabolite pool influx is mainly due to the depolymerization of HMW organic compounds by extracellular enzyme activities, influx is reflected in the change in the concentration of 14N metabolites and decreases in their 15N/14N ratios. There was a significant increase in the 14N proline concentration and a parallel decrease in 15N isotopic composition in the samples quenched at 25 °C, which provides a clear demonstration of considerable extracellular enzyme activity (Figure 1). In contrast, the enzymatic activity and pool influx were negligible at 4 °C for both glucosamine and proline. Therefore, in the absence of formaldehyde, extraction with 1 M KCl at 4 °C effectively quenched extracellular enzyme activity and microbial uptake, minimizing influx and efflux of soil extracellular metabolites during extraction while providing sufficient extraction recoveries of soil amino compounds.

Figure 1.

Quenching efficiency of the extraction protocol for extracellular amino sugars and amino acids by 1 M KCl. The kinetics of the concentrations of 15N labeled and unlabeled glucosamine and proline in an agricultural soil suspension (1 M KCl) are shown over time, before being filtered and freeze dried. Extractions and standing times of 30, 60, and 90 min were performed at three temperatures, i.e., 4, 15, and 25 °C. Values are the mean ± 1 SD (n = 3).

Soil Amino Acid and Amino Sugar Dynamics

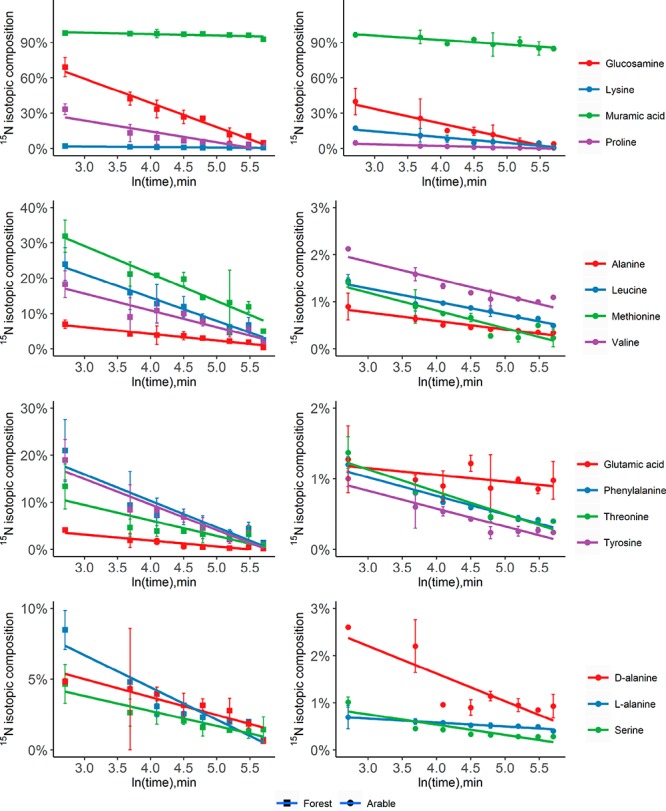

The developed IPD assay was applied to a forest and an arable soil to investigate the dynamics and transformation rates of extracellular amino compounds. At constant rates of production and consumption of a soil metabolite, isotope ratios exponentially decline, which can be shown as a linear relationship when plotted against the natural logarithm of time (Figure 2). The decrease of the ratios of 15N tracer/14N tracee in these plots followed a linear pattern, and good linearity (R2 > 0.95) was observed for most metabolites, indicating that the transformation rates of these metabolites fit the analytical solution of the IPD model.

Figure 2.

Changes in 15N isotopic composition (at % 15N) of amino sugars and amino acids over time. Isotope pool dilution causes exponential declines in at % 15N of individual pools, which becomes linear when plotted against ln(time) as shown here. 15N labeled mixes of amino sugars and amino acids were amended to a forest soil (left) and an arable soil (right), and assays were stopped at different times by extraction with 1 M KCl. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Table S5 summarizes the pool sizes, gross rates of influx and efflux, and mean residence times of free amino acids and amino sugars in the two soils. The composition of the amino compound pool showed significant differences between individual compounds and across soils. The three dominant metabolites accounted for more than 50% of the total amino compound pool, which were glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and arginine in the forest soil and glutamic acid, lysine, and aspartic acid in the arable soil. Moreover, we here report the first measurements of concentrations of free muramic acid and mDAP and among the first measurements of d/l isomers of free alanine and glutamate in soil extracts.16 Glucosamine and mDAP showed similar concentrations compared to those of most amino acids, ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 μg N g–1 and from 0.07 to 0.11 μg N g–1, respectively, whereas muramic acid exhibited very low concentrations (<0.01 μg N g–1). Moreover, the d/l ratios of free alanine and glutamic acid in soil varied from 0.04 to 0.5, which is similar to the finding of Kunnas for soil hydrolysates.41 Mean residence times (MRTs) were calculated by dividing the concentration of free metabolites by their mean influx and efflux rates, with the MRTs differing markedly between compounds and soil types. The lowest MRT was found for mDAP (<0.6 h), and the highest was found for muramic acid, with a MRT of 18.7 h. Other amino acids as well as glucosamine showed similar MRTs, ranging from 0.4 to 3.5 h (1.4 ± 0.8 h, average ± 1 SD of 17 amino acids), which were shorter than those measured from respiratory use of 14C labeled amino acids added to soils.42

The influx of individual metabolites showed very large variation, ranging from 1 × 10–5 to 4.8 μg N g–1 d.w. d–1. In addition to the high influx rates of individual amino acids (Asp, Glu, Arg), most of the amino acids exhibited rates of approximately 0.05–1 μg N g–1 d.w. d–1. Pool sizes and flux rates were strongly positively correlated across the different metabolites. In a log–log plot, influx rates increased with concentration (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.78) as did efflux rates (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.70), and influx and efflux rates were also strongly related (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.88). Transformation rates were on average similar for d-amino acids, as compared to l-amino acids, a finding consistent with comparable uptake and respiratory use of d- compared to l-enantiomers of free amino acids in soils.43,44 Glucosamine accounted for approximately 4–7% of the total influx into the free amino compound pool, indicating that peptidoglycan and chitin decomposition represent an important input to the labile soil N pool besides protein decomposition. Accounting for the additional influx of muramic acid, mDAP, and the d-amino acid isomers, the contribution increased to 9–14%. Surprisingly, although muramic acid has a chemical structure similar to glucosamine (muramic acid being a lactic acid ether of glucosamine), it exhibited extremely low influx and efflux rates, indicating that free muramic acid is not a major metabolite produced during peptidoglycan decomposition in soils and therefore is also not an important organic N source for soil microbes. Therefore, muropeptides or N-acetylmuramic acid could possibly represent the major muramic acid-containing decomposition products of peptidoglycan.

It is worth noting that the proportion of influx of amino sugars and d-amino acids differed between forest and arable soils, which can be used to estimate the proportion of bacterial versus fungal cell wall decomposition. This is because free glucosamine in soils originates from the cell walls of both fungi and bacteria (i.e., chitin and peptidoglycan), whereas muramic acid, d-alanine, and d-glutamic acid originate from bacteria only. In addition, mDAP exists only in the peptidoglycan of (most) Gram-negative bacteria. We observed a higher influx of mDAP and d-glutamic acid in forest soil but a lower influx in glucosamine, muramic acid, and d-alanine. These findings indicate that in the forest soil there was a higher contribution of decomposition of Gram-negative bacteria and of fungal necromass compared to that in arable soil. The method therefore holds great potential for flux partitioning in terms of bacterial and fungal contributions to amino compound fluxes in soils.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed a comprehensive IPD assay to quantify the in situ flux of free extracellular amino sugars and amino acids in soil. For the first time, HRMS was applied in soil fluxomics, which allowed us to measure the 15N tracer level and simultaneously the 13C-IS in a complex sample matrix. Uniformly 13C labeled IS proved to be sufficient for correction of matrix effects and losses during the purification procedure. Importantly, our approach shows great potential to be applied for other target metabolites, such as nucleotides, organic acids, and sugars, using high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with anion suppression.45

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; project P-28037-B22). The authors would like to thank Stephanie A. Eichorst and Dagmar Woebken for their assistance in B. subtilis cultivation.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01938.

Soil sampling procedure and selected properties of the soil samples; purity of isolated peptidoglycan and isotope labeling efficiency in the hydrolysates of 15N and 13C labeled peptidoglycan; concentrations of amino sugars and amino acids in the 15N tracer mix and 13C internal standards; isotope calibration for amino compounds with LC/MS; concentrations of free amino sugars and amino acids of a forest and an arable soil; extracted ion chromatograms; mass spectrometric separation of isobaric 15N-glycine and 13C1-glycine; recovery of selected metabolites on different cation-exchange resins (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Swenson T. L.; Jenkins S.; Bowen B. P.; Northen T. R. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 80, 189–198. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M.; Prendergast-Miller M.; Jones D. L.; Hill P. W.; Condron L. M. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 261–267. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Amelung W. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1996, 28, 1201–1206. 10.1016/0038-0717(96)00117-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulten H. R.; Schnitzer M. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1997, 26, 1–15. 10.1007/s003740050335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borruat G.; Roten C.-A. H.; Marchant R.; Fay L.-B.; Karamata D. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 922, 219–224. 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)00934-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B.; Turrión M. a.-B.; Alef K. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 399–407. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2003.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veuger B.; Middelburg J. J.; Boschker H. T. S.; Houtekamer M. Limnol. Oceanogr.: Methods 2005, 3, 230–240. 10.4319/lom.2005.3.230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M.; Hill P. W.; Farrar J.; Bardgett R. D.; Jones D. L. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 835–844. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanek W.; Mooshammer M.; Blöchl A.; Hanreich A.; Richter A. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1293–1302. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mooshammer M.; Wanek W.; Schnecker J.; Wild B.; Leitner S.; Hofhansl F.; Blöchl A.; Hämmerle I.; Frank A. H.; Fuchslueger L.; Keiblinger K. M.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern S.; Richter A. Ecology 2012, 93, 770–782. 10.1890/11-0721.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild B.; Schnecker J.; Knoltsch A.; Takriti M.; Mooshammer M.; Gentsch N.; Mikutta R.; Alves R. J.; Gittel A.; Lashchinskiy N.; Richter A. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2015, 29, 567–582. 10.1002/2015GB005084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimel J. P.; Bennett J. Ecology 2004, 85, 591–602. 10.1890/03-8002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C. R. Plant Soil 2014, 375, 1–19. 10.1007/s11104-013-1939-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts P.; Bol R.; Jones D. L. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 3081–3092. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C. R. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 57, 444–450. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C. R. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 44–55. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe R. R.; Chinkes D. L.. Isotope Tracers in Metabolic Research: Principles and Practice of Kinetic Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Apostel C.; Dippold M.; Glaser B.; Kuzyakov Y. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 67, 31–40. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apostel C.; Dippold M.; Kuzyakov Y. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 80, 199–208. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanek W.; Heintel S.; Richter A. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001, 15, 1136–1140. 10.1002/rcm.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitner S.; Wanek W.; Wild B.; Haemmerle I.; Kohl L.; Keiblinger K. M.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern S.; Richter A. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 50, 174–187. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrasio R.; Haberhauer-Troyer C.; Mattanovich D.; Koellensperger G.; Hann S. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 915–922. 10.1007/s00216-013-7456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K. B.; Turko I. V.; Phinney K. W. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 4429–4435. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer S.; Haberhauer-Troyer C.; Klavins K.; Russmayer H.; Steiger M. G.; Gasser B.; Sauer M.; Mattanovich D.; Hann S.; Koellensperger G. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 35, 3091–3105. 10.1002/jssc.201200447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvitvang H. F.; Andreassen T.; Adam T.; Villas-Boas S. G.; Bruheim P. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 2705–2711. 10.1021/ac103245b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C. R. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 233–242. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.; Creek D. J.; Barrett M. P.; Blackburn G.; Watson D. G. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 1994–2001. 10.1021/ac2030738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszewski B.; Noga S. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 402, 231–247. 10.1007/s00216-011-5308-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You L.; Zhang B.; Tang Y. J. Metabolites 2014, 4, 142–165. 10.3390/metabo4020142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W.; Clasquin M. F.; Melamud E.; Amador-Noguez D.; Caudy A. A.; Rabinowitz J. D. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 3212–3221. 10.1021/ac902837x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. A.; Farnsworth C.; Yu W.; Bonilla L. E. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 880–885. 10.1021/pr100780b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge B. L.; Chang Y. S.; Gage D.; Tomasz A. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 11248–11254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham D.; Bartholomew W. V. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1955, 19, 189. 10.2136/sssaj1955.03615995001900020020x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atrih A.; Bacher G.; Allmaier G.; Williamson M. P.; Foster S. J. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 3956–3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spagou K.; Tsoukali H.; Raikos N.; Gika H.; Wilson I. D.; Theodoridis G. J. Sep. Sci. 2010, 33, 716–727. 10.1002/jssc.200900803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry H.; Sobhi H. R.; Scheibner O.; Bromirski M.; Nimkar S. B.; Rochat B. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 26, 499–509. 10.1002/rcm.6121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.; Helmus R.; Cerli C.; Jansen B.; Wang X.; Kalbitz K. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1449, 78–88. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros G. H.; Hoffland E.; van Kessel C.; Temminghoff E. J. M. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1029–1039. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Needham T. E.; Paruta A. N.; Gerraughty R. J. J. Pharm. Sci. 1971, 60, 565–567. 10.1002/jps.2600600410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho S. P.; Macedo E. A. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2005, 50, 29–32. 10.1021/je049922y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunnas A. V.; Jauhiainen T. P. J. Chromatogr. A 1993, 628, 269–273. 10.1016/0021-9673(93)80010-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 209–219. 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00175-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vranova V.; Zahradnickova H.; Janous D.; Skene K. R.; Matharu A. S.; Rejsek K.; Formanek P. Plant Soil 2012, 354, 21–39. 10.1007/s11104-011-1059-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G.; Sun H. J. PLoS One 2014, 9, e92101. 10.1371/journal.pone.0092101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Christison T. T.; Misuno K.; Lopez L.; Huhmer A. F.; Huang Y.; Hu S. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 5116–5124. 10.1021/ac500951v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.