Abstract

To our knowledge, no studies have examined the role of IL-17 production by neutrophils in immune defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) infection and the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) caused by MTB infection. Here, we determined that neutrophils express IL-17 in an autocrine IL-6- and IL-23-dependent manner during MTB infection. MTB H37Rv-induced IL-6 production was dependent on the NF-κB, p38, and JNK signaling pathways; however, IL-23 production was dependent on NF-κB and EKR in neutrophils. Furthermore, we found that Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 mediated the activation of the kinases NF-κB, p38, ERK, and JNK and the production of IL-6, IL-23, and IL-17 in neutrophils infected with MTB H37Rv. Autocrine IL-17 produced by neutrophils played a vital role in inhibiting MTB H37Rv growth by mediating reactive oxygen species production and the migration of neutrophils in the early stages of infection. However, IL-17 production by neutrophils contributed to collagen-induced arthritis development during MTB infection. Our findings identify a protective mechanism against mycobacteria and the pathogenic role of MTB in arthritis development.

Keywords: Neutrophil, Ll-17, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Rheumatoid arthritis

Highlights

-

•

Neutrophils were able to express IL-17 in a dependent on the autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 manner during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection.

-

•

Autocrine IL-17 in neutrophils played a vital role in inhibiting Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth.

-

•

IL-17 production in neutrophils contributed to collagen-induced arthritis development during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection.

1. Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), the main causal pathogen in tuberculosis, has infected one-third of the world's population and has become a severe threat to human health. Upon infection with MTB, several factors contribute to the disease outcome, and cell-mediated immunity represents one of the most critical determinants (Dorhoi et al., 2011, Cooper, 2009). To date, several cells have been shown to participate in the host response against MTB, such as T cells, macrophages, dendritic cells and neutrophils (Sia et al., 2015, Lerner et al., 2015). Due to the host immune responses, only 10% of affected individuals show evidence of symptoms and develop the clinical disease. However, there are still estimated 8–9 million new cases and 2–3 million deaths from tuberculosis annually. Furthermore, because MTB is a strong immunogen and often results in an uncontrolled immune responses (Dorhoi et al., 2011), MTB infection is associated with many autoimmune diseases, e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus (Singh et al., 2013), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Shen et al., 2015) and multiple sclerosis (Fragoso et al., 2014). RA is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by synovitis leading to the destruction of articular cartilage and bone. Several studies have demonstrated that MTB is capable of promoting the development of RA in patients and in a mouse model (Shen et al., 2015, Kanagawa et al., 2015). Extensive clinical investigations have shown that a previous history of tuberculosis is associated with RA (Shen et al., 2015). The relationship between the immune system and MTB is highly complex and is not yet fully understood. To study host immune responses initiated by MTB infection, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms of MTB immune control and the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases associated with MTB infection.

Neutrophils are an essential component of the innate immune system; they act as a first line of defense against invading microorganisms and fungi (Eum et al., 2010, Borregaard, 2010). These highly motile cells are rapidly recruited to infection sites and can destroy invading pathogens by both oxidative and nonoxidative mechanisms, i.e., by the phagocytosis of the microorganisms themselves or by the extracellular release of microbicidal granules (Amulic et al., 2012). In MTB infection, neutrophils form the bulk of the early recruited leukocyte population involved in immune responses against MTB (Martineau et al., 2007). After recognizing MTB via pattern recognition receptors, especially Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 (Akira et al., 2006), neutrophils exhibit phagocytosis, which in turn triggers signaling events resulting in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Yang et al., 2012) and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-23 and TNF-α (Bardoel et al., 2014, Mantovani et al., 2011), which mediate early inflammatory responses (Lowe et al., 2012). Noteworthy, while neutrophils provide immune protection against pathogens, they also promote tissue injury in inflammatory diseases and contribute to autoimmune diseases via the production of cytokines.

IL-17A (referred to as ‘IL-17’ here) contributes to protection against bacterial infections, but also to the pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory disease (Iwakura et al., 2011). Studies have shown the importance of IL-17 in various physiological and pathophysiological processes, including host defense against MTB infections (Torrado and Cooper, 2010) and RA (Pope and Shahrara, 2013). Although the Th17 subset of helper T cells is considered to be the main source of IL-17, natural killer T cells (NKT cells), γδ T cells and innate lymphoid cells produce IL-17 more rapidly than do T cells (Cua and Tato, 2010, Isailovic et al., 2015). Neutrophils have also been identified as a source of IL-17 in human psoriatic lesions (Lin et al., 2011), patients with corneal ulcers caused by filamentous fungi (Karthikeyan et al., 2011), and several mouse models of infectious and autoimmune inflammation (Ferretti et al., 2003, Hoshino et al., 2008, Li et al., 2010). No studies have examined the role of IL-17 production by neutrophils in immune defense against MTB infection and the pathogenesis of RA associated with MTB infection.

In the present study, we found that after infection with MTB, neutrophils expressed Il17a transcripts as well as the IL-17 protein, and this expression was dependent on not only paracrine IL-6 and IL-23, but also on autocrine IL-6 and IL-23. IL-6 and IL-23 levels in neutrophils were regulated by different pathways mediated by TRL2 and TLR4. On the one hand, MTB-induced IL-17 production by neutrophils increased MTB killing activity by enhancing ROS production and the migration of inflammatory cells at the early stage of infection; on the other, it promoted arthritis severity in a collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

All animal experiments in this study were carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Board and the Biosafety Management Committee of Southern Medical University (approval number SMU-L2016003). Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Institutional Review Board of the Southern Medical University. Written informed consents were obtained from all participants for the use of PBMC samples.

2.2. Mice

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Lab Animal Center of Southern Medicine University (Guangzhou, China). TLR2-deficient (Tlr2−/−), Tlr4−/−, Cd18−/− and Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from Nanjing Biomedical Research Institute (Nanjing, China). Il6−/−, Il17a−/− and IL-17A-GFP mice on a C57BL/6 background were purchased from Shanghai Research Center for Model Organisms (Shanghai, China). All mice were maintained in the Lab Animal Center of Southern Medicine University under specific pathogen-free conditions.

2.3. MTB Infection of Mice

8-week-old female mice were inoculated intratracheally (i.t.) with 1 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU) of MTB H37Rv in 50 μl of PBS. Bacterial burden was determined by plating serial dilutions of lung and spleen homogenates onto 7H10 agar plates (BD Difco, USA) supplemented with 10% OADC. Plates were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 3 weeks before counting colonies.

2.4. Preparation of Splenocyte Supernatants

After 3 days, serum was collected from blood obtained from the retro-orbital sinuses, and then MTB-infected mice were asphyxiated by inhalation of CO2 and spleens were removed. Single-cell suspensions were prepared, red blood cells were lysed and 1 × 106 spleen cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) containing 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 18 h. The cultural supernatants of splenocytes were collected.

2.5. Isolation of Mouse Bone Marrow Neutrophils

Total bone marrow cells were recovered from the femurs and tibias by flushing with RPMI medium with an 18-gauge needle; erythrocytes were lysed with a commercial lysis buffer (eBioscience, USA) and bone marrow cells were separated by density centrifugation with a discontinuous Percoll gradient (52%, 69% and 78%; Fisher, USA). Cells at the 69%–78% interface were harvested, and neutrophil purity (> 98%) was confirmed by flow cytometry.

2.6. Human Neutrophils

Human neutrophils were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors by Ficoll centrifugation. Neutrophil layer was washed and assessed by flow cytometry.

2.7. In Vitro Stimulation

Mouse and human neutrophils, suspended at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml, were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by culture with MTB H37Rv at a MOI of 5, 100 ng/ml LPS, 100 ng/ml Pam3CSK4, mixture of Pam3CSK4 and LPS or PBS. For cytokine-neutralization studies, 20 μg/ml (final concentration) of antibody to mouse or human IL-6, IL-23, IL-1β or TGF-β (R&D, USA) was added into supernatants of splenocytes or neutrophils 2 h before stimulation in vitro. For signal pathway-inhibition studies, the NF-κB-inhibitor JSH-23, PI3K-inhibitor LY294002, MEK1/2-inhibitor U0126, p38 inhibitor-SB203580 or JNK-inhibitor SP600125 (Selleck, USA) was added into supernatants of neutrophils.

2.8. Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For mRNA, first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). An Eppendorf Master Cycle Realplex2 and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) were used for real-time PCR (40 cycles). PCR products were then separated by electrophoresis through a 1% agarose gel and were visualized by being stained with ethidium bromide. The primer sequences used for PCR are in Supplementary Table 1.

2.9. Flow Cytometry

For surface staining, neutrophils were harvested, washed and stained for 30 min on ice with mixtures of fluorescently conjugated mAbs or isotype-matched controls. mAbs of human were as follows: FITC-CD15, PE-CD16 (eBioscience). mAbs of mice were as follows:PE-CD11b, FITC-Gr-1 (eBioscience). For intracellular staining, cells were incubated 20 min in IC Fixation buffer (eBioscience), followed by permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) and 1 h of incubation with appropriate antibodies:APC-IL-17. Cell phenotype was analyzed by flow cytometry on a flow cytometer (BD LSR II) (BD Biosciences, USA). Data were acquired as the fraction of labeled cells within a live-cell gate and analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star). All gates were set on the basis of isotype-matched control antibodies.

2.10. ELISA

Cytokines were quantified by two-site enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer's directions (R&D).

2.11. Western Blotting

Cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and then lysed in lysis buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% (vol/vol) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich, USA), and 1 mM DTT. Equal amounts (20 mg) of cell lysates were resolved using 8–15% polyacrylamide gels transferred to PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in PBST and incubated overnight with the respective primary antibodies at 4 °C. The membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualized with Plus-ECL (PerkinElmer, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.12. Neutrophil Depletion Assay

For neutrophil depletion, 0.5 mg of 1A8 monoclonal (anti m Ly-6G; BioXcell, USA) was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) for 4 days once a day from the day before the infection. 2A3 isotype control Ab (Rat IgG2a; BioXcell) was also injected i.p. as control. To evaluate neutrophil depletion, blood samples from orbital were withdrawn and analyzed by flow cytometry after staining with PE anti-CD11b (eBioscience) and FITC anti-Gr-1 antibody (eBioscience).

2.13. In Vitro MTB Killing Assay

Neutrophils were allowed to adhere to 24-well flat bottom plates at 5 × 105 cells per well and infected with MTB H37Rv at a MOI of 5 for 1 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2, then wells were extensively washed with pre-warmed PBS to remove non-adherent bacteria. The cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for time points up to 24 h, and then were lysed in 1 ml of distilled water. Bacterial burden was determined by plating serial dilutions onto 7H10 agar plates supplemented with 10% OADC. Plates were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 3 weeks before counting colonies. All infections were performed in triplicate.

2.14. Adoptive Transfer

Cd18−/− mice were infected with MTB H37Rv as described above. After 3 h, bone marrow neutrophils from WT or Il17a−/− mice were isolated, washed and adoptively transferred via tail vein into Cd18−/− recipient mice (2 × 106 cells/mouse/2 days) in 100 μl of PBS. MTB H37Rv-infected mice were sacrificed on different days. Lung from some infected mice were collected and digested in collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at different days, and cells were incubated with Gr-1. Bacterial burden was determined by plating serial dilutions of lung and spleen homogenates onto 7H10 agar plates supplemented with 10% OADC. In a second mouse model, Cd18−/− recipient mice were used to induce CIA model.

2.15. CIA Model

CIA was induced in C57BL/6 mice as previously described(Brand et al., 2007). The experimental CIA model was generated by injecting 100 μl of an emulsion containing 100 μg of chicken type II collagen (Sigma Aldrich) intradermally at the base of the tail. The basic emulsion was composed of 2 mg/ml chicken type II collagen dissolved in PBS and an equal volume of complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) with 5 mg/ml of desiccated MTB H37Ra (Difco). At 21 days after the first injection, the second immunizations were performed. Clinical symptoms of arthritis were then evaluated visually in each limb and graded on a scale of 0–4; 0 = no evidence of erythema and swelling, 1 = erythema and mild swelling confined to the tarsals or ankle joint, 2 = erythema and mild swelling extending from the ankle to the tarsals, 3 = erythema and moderate swelling extending from the ankle to metatarsal joints, 4 = erythema and severe swelling encompass the ankle, foot and digits, or ankylosis of the limb. The clinical score for each mouse was calculated as the sum of scores for all four limbs (maximum score 16). At the time mice were killed, paws were removed and fixed in 10% (vol/vol) neutral-buffered formalin for at least 2 days. Joints were decalcified for at least 2 days in decalcification buffer (0.4 M HCl, 0.5 M acetic acid, 0.2 M chloroform in 70% [vol/vol] ethanol), which was changed daily. Joints were then embedded in paraffin and frontal sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

2.16. Statistical Analysis

An unpaired t-test and one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post-hoc analysis (Prism; GraphPad Software) was used for statistical analysis of each experiment using. A P value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. MTB H37Rv Induced IL-17 Production of Neutrophils

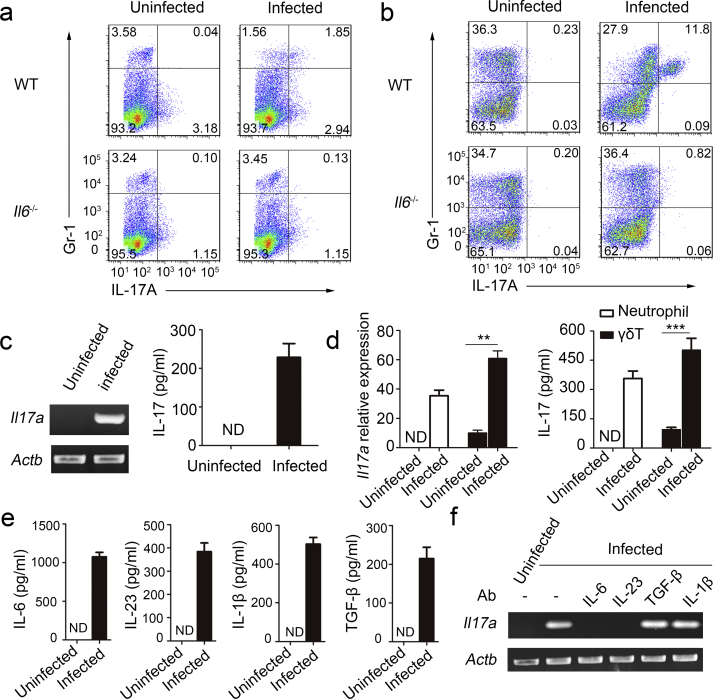

To determine if neutrophils could be induced to express IL-17 by MTB H37Rv, we injected wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice and Il6−/− mice intratracheally with MTB H37Rv. Three days later, we examined IL-17 production in neutrophils from the spleens of naive mice and from those of infected mice by intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry. We found that Gr-1+ neutrophils isolated from infected WT mice, but not naive or Il6−/− mice, contained intracellular IL-17 (Fig. 1a). Total bone marrow cells from naive mice or from infected mice were isolated, and incubated in the supernatants of splenocytes from the same mice. We found that there were no bone marrow cells stimulated by supernatants of splenocytes from naive mice with intracellular IL-17, but 11.8% of bone marrow cells stimulated by supernatants of splenocytes from WT infection mice, which were all Gr-1+ (Fig. 1b). In contrast, we did not detect IL-17+ bone marrow cells in Il6−/− mice (Fig. 1b). Gr-1+ bone marrow cells from infected Rag2−/− Il2rg−/− mice (T cell and natural killer (NK) cell deficiency) were also positive for IL-17, indicating that T cells and NK cells were not required for IL-17 production by neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Induction of IL-17-producing neutrophils during MTB H37Rv infection. Wild type (WT) and Il6−/− mice were intratracheally (i.t.) infected with MTB H37Rv for three days. (a) Splenocytes were incubated with anti-Gr-1, permeabilized and incubated with anti-IL-17, and examined by flow cytometry. Numbers in quadrants indicate percent cells in each throughout. (b) Bone marrow cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium with splenocyte supernatant from the same mouse. And then after 18 h, these cells were incubated with anti-Gr-1, permeabilized and incubated with anti-IL-17, and examined by flow cytometry. (c) Purified neutrophils from total bone marrow cells of infected or uninfected WT mice were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium with splenocyte supernatant from the same mouse. Il17a gene expression in purified neutrophil populations was examined by PCR. PCR products were qualitatively examined on 1% agarose gel. Concentration of IL-17 in supernatant was detected by ELISA. (d) Purified neutrophils and γδT from spleen of infected or uninfected WT mice were incubated for 18 h in RPMI 1640 medium with splenocyte supernatant from the same mouse. Il17a gene expression in purified neutrophil populations was examined by quantitative PCR. Il17a gene quantitie was normalized to the expression of the reference gene β-actin. Concentration of IL-17 in supernatant was detected by ELISA. (e) Cytokine production by splenocytes obtained from infected or uninfected WT mice. ND, not detected. (f) Il17a expression in purified bone marrow neutrophils incubated in RPMI 1640 medium with splenocyte supernatant from the same mouse plus no antibody (-) or neutralizing antibody (Ab) to IL-1β, TGF-β, IL-6 or IL-23 (above lanes). Actb (which encodes β-actin) serves as a loading control throughout. Data shown in (d–f) are the mean ± SEM. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

Furthermore, to assess IL-17 expression, neutrophils were isolated from the bone marrow and spleen by gradient centrifugation (> 98% Gr-1+) (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and isolated neutrophils were not contaminated by γδT (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Neutrophils stimulated by the supernatants of splenocytes from MTB H37Rv-infected WT mice expressed Il17a mRNA and IL-17 protein, but those stimulated by the supernatants of splenocytes from naive mice did not (Fig. 1c, d). In addition, γδT cells could also be stimulated to produce IL-17.

Studies have reported that IL-6, IL-23, IL-1β and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) mediate IL-17 expression in lymphoid cells (Korn et al., 2009), but only IL-6 and IL-23 are potential inducers of IL-17 production in neutrophils (Taylor et al., 2014). Because the supernatant of splenocytes was able to induce IL-17 expression in neutrophils, we investigated the soluble factors responsible for the induction of IL-17 in neutrophils. We found that the supernatants of splenocytes from MTB H37Rv-infected WT mice had high concentrations of IL-6, IL-23, IL-1β and TGF-β (Fig. 1e). Importantly, neutrophils were isolated and incubated for 1 h with supernatants of splenocytes in the presence of neutralizing antibodies and Il17a expressions levels were analyzed by quantitative PCR. Neutralization of either IL-6 or IL-23, but not IL-1β or TGF-β, in the supernatants of splenocytes ablated its IL-17 induction activity (Fig. 1f). Together, these results demonstrated that in response to MTB infection, neutrophils expressed transcripts encoding IL-17 as well as the IL-17 protein, and IL-6 and IL-23 are required for the induction of IL-17.

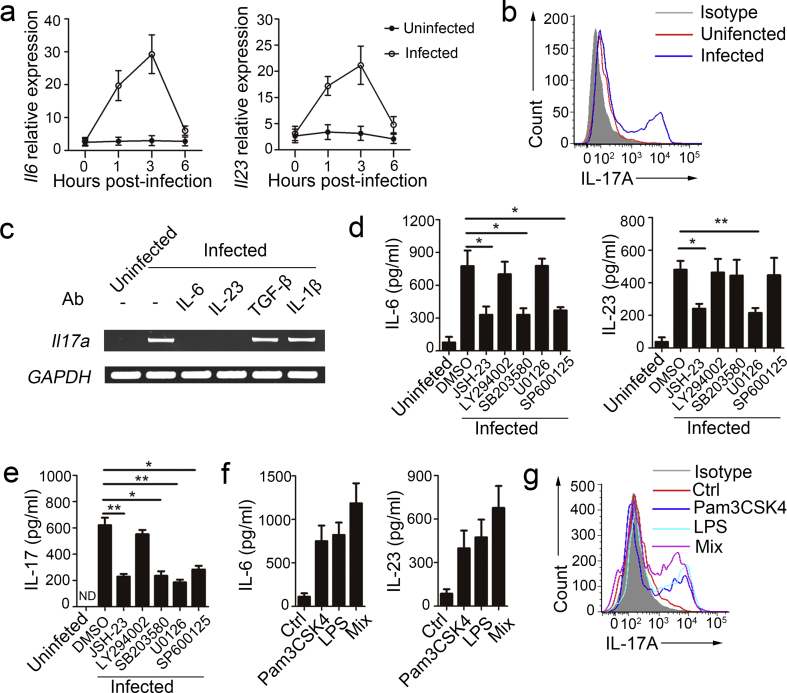

3.2. Autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 Induced IL-17 Production in Neutrophils With MTB H37Rv Infection

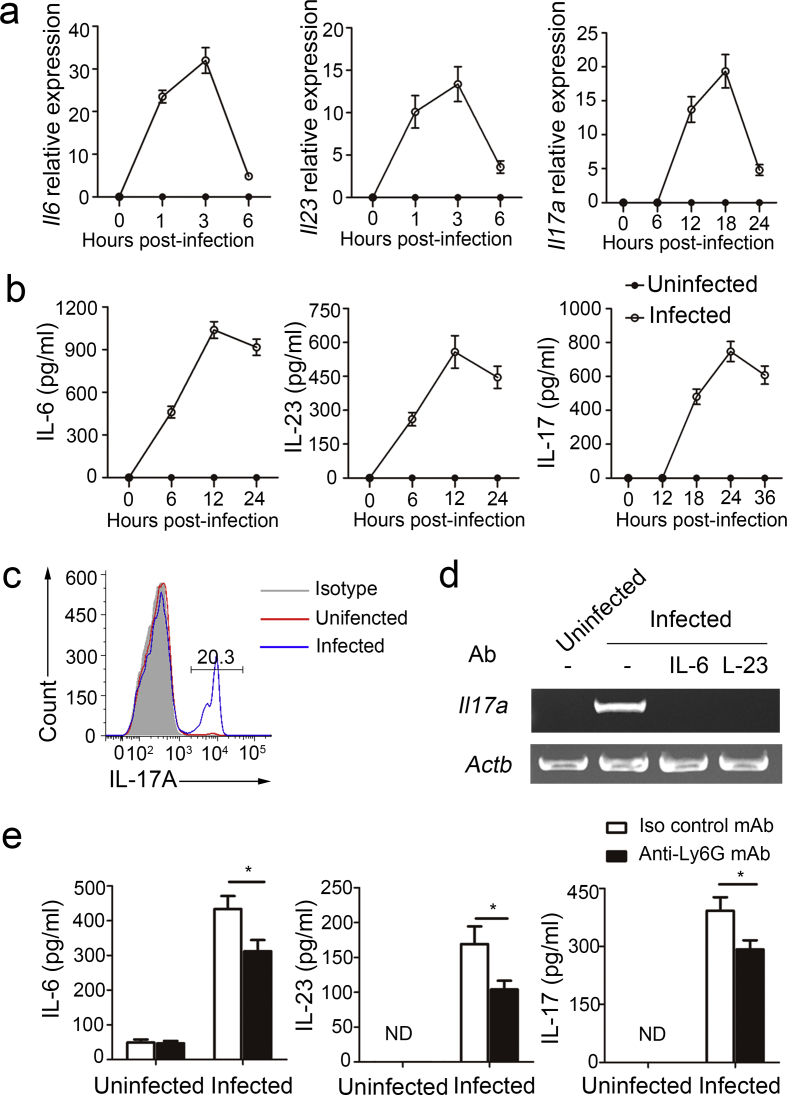

Because neutrophils are also the main source of IL-6 and IL-23 in immune responses, mediating the severity of autoimmune diseases and contributing to protection against bacterial infections (Morris et al., 2013, D'Elios et al., 2007, Kvedaraite et al., 2016), we examined the roles of autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 in IL-17 production by neutrophils during MTB H37Rv infection. We detected Il6, Il23, and Il17a mRNA (Fig. 2a) and IL-6, IL-23, and IL-17 protein (Fig. 2b) in purified neutrophils infected with MTB H37Rv in vitro. Furthermore, 20.3% of total neutrophils were IL-17+ 24 h after MTB H37Rv infection (Fig. 2c). Of note, IL-17 expression displayed a delayed kinetics compared to IL-6 and IL-23, suggesting that the inducible expression of IL-17 was potentially related to autocrine IL-6 and IL-23. Furthermore, neutrophils isolated from IL-17A-GFP mice and infected with MTB H37Rv contained intracellular IL-17, but those from naive IL-17A–GFP mice did not (Supplementary Fig. 2a). We used PCR to confirmed that Il17a was lacking after the neutralization of either IL-6 or IL-23 (Fig. 2d). The receptors for IL-17A contain IL-17RA and IL-17RC subunits. IL-17RC is not constitutively expressed by neutrophils, but can be inducibly expressed (Taylor et al., 2014). Consistent with previous reports, we found that IL-17RC expression could be induced after MTB H37Rv infection (Supplementary Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 induced IL-17 production in neutrophils with MTB H37Rv infection. (a) Il6, Il23 and Il17a mRNA expression in neutrophils infected with MTB H37Rv for indicated time points determined by real-time PCR. All gene quantities were normalized to the expression of the reference gene β-actin. (b) IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 secretion by neutrophils infected with MTB H37Rv for indicated time points was measured by ELISA. (c) Expression of intracellular IL-17 by neutrophils uninfected or infected with MTB H37Rv for 24 h. (d) Il17a expression in neutrophils infected with MTB H37Rv for 18 h plus no antibody (-) or neutralizing antibody (Ab) to IL-6 or IL-23. (e) WT mice were infected with MTB H37Rv, and then treated with either isotype control mAb or anti-Ly6G mAb for 4 days once a day from the day before the infection. Concentrations of IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 in serum were quantified. Data shown in (a–c, e) are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

Because Ly6G is mainly expressed in neutrophils and the anti-Ly6G monoclonal antibody (mAb) is widely used for neutrophil depletion studies (Daley et al., 2008), the anti-Ly6G mAb was used to directly assess if neutrophils are the source of IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 in mice with MTB H37Rv infection. The anti-Ly6G mAb specifically depleted neutrophils, but not monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Serum from anti-Ly6G mAb-treated mice had lower concentrations of IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 than those of serum from isotype control mAb-treated mice (Fig. 2e). Together these observations indicated that autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 induced IL-17 production by neutrophils in MTB H37Rv infection.

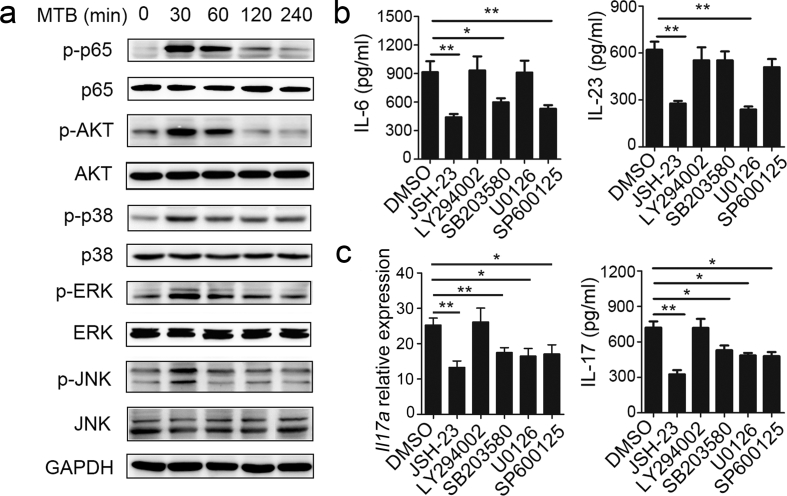

3.3. MTB H37Rv-induced IL-6 Production was Dependent on the NF-κB, p38 and JNK Signaling Pathways and IL-23 Production was Dependent on NF-κB and EKR in Neutrophils

Neutrophils are the main source of IL-6 and IL-23, but the specific molecular pathways that mediate IL-6 and IL-23 production in neutrophils remain unknown. The production of many cytokines by neutrophils is known to be regulated by NF-κB-, PI3K-AKT-, or MAPK (ERK, p38, and JNK)-dependent signaling pathways; accordingly, we evaluated the role of these pathways in IL-6, IL-23, and IL-17 production by neutrophils in MTB H37Rv infection. We found that stimulation of neutrophils with MTB H37Rv led to enhanced phosphorylation of NF-κB p65, AKT, ERK1/2, p38, and JNK (Fig. 3a). We then used the NF-κB inhibitor JSH-23, PI3K inhibitor LY294002, MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126, p38 inhibitor SB203580, and JNK inhibitor SP600125 and found that the phosphorylation of these proteins was decreased for a range of inhibitor concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 3). Next we examined the effect of inhibiting the phosphorylation of these proteins on IL-6 and IL-23 production. We found that JSH-23, SB203580, and SP600125 observably inhibited IL-6 production, but LY294002 and U0126 no effect (Fig. 3b). IL-23 production was inhibited by JSH-23 and U0126, but not by SB203580, LY294002 or SP600125 (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, Il17a mRNA levels and IL-17 protein levels after induction by MTB H37Rv were significantly reduced in neutrophils treated with JSH-23, U0126, SB203580, and SP600125 (Fig. 3c). These findings demonstrate that MTB H37Rv-induced IL-6 production was dependent on the NF-κB, p38 and JNK signaling pathways and IL-23 production was dependent on NF-κB and EKR in neutrophils. Autocrine IL-6 and IL-23-induced IL-17 production in neutrophils with MTB H37Rv infection was regulated by various signaling pathways.

Fig. 3.

MTB H37Rv-induced IL-6 and IL-23 production in neutrophils dependent on different pathways. (a) Neutrophils were infected with MTB H37rv for the indicated time points, followed by immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated p65 (p-p65), p65, p-AKT, AKT, p-p38, p38, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK and GAPDH with cell lysates. (b–c) Neutrophils were infected with MTB H37Rv alone or in the presence of the NF-κB-inhibitor JSH-23 (20 μM), PI3K-inhibitor LY294002 (30 μM), MEK1/2-inhibitor U0126 (40 μM), p38 inhibitor-SB203580 (10 μM) or JNK-inhibitor SP600125 (20 μM). The DMSO-treated neutrophils were as control (Ctrl) group. (b) Supernatants were collected after 12 h, and IL-6 and IL-23 concentrations in supernatants were quantified by ELISA. (c) Il7a expression was evaluated by real-time PCR at 18 h after infection and IL-17 concentrations in supernatants were quantified at 24 h. All gene quantities were normalized to the expression of the reference gene β-actin. Data shown in (b and c) are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

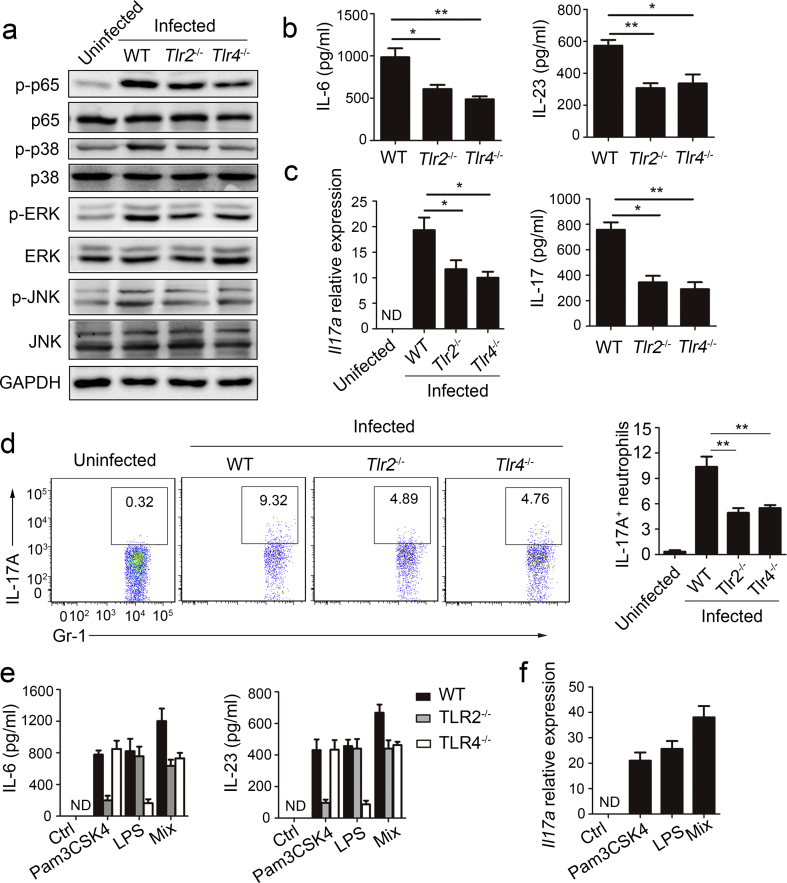

3.4. MTB H37Rv-induced IL-6 and IL-23 Production by Neutrophils was Dependent on TLR2 and TLR4

Pattern recognition receptors play a major role in triggering proinflammatory cytokine production and phagocytic antimicrobial pathways in MTB infection, especially TLR2 and TLR4. To examine whether these TLRs are responsible for the MTB H37Rv-induced IL-6 and IL-23 cytokine responses, neutrophils were isolated from the bone marrow of Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− mice and infected with MTB H37Rv in vitro. We found that the phosphorylation of p65, AKT, p38, ERK, and JNK was suppressed in Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− neutrophils compared to WT neutrophils (Fig. 4a). To assess the expression of IL-6 and IL-23, we performed ELISA and found that IL-6 and IL-23 expression levels were markedly lower in the supernatants of Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− neutrophils than in the supernatants of WT neutrophils (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, we tested the roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in IL-17 production by neutrophils. In response to MTB H37Rv stimulation, Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− neutrophils reduced intracellular IL-17 production as well as extracellular IL-17 secretion (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

TLR2 and TLR4 mediated IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 production in neutrophils. (a–d) Neutrophils were isolated from total bone marrow cells of WT, Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− mice, and then infected with MTB H37Rv. (a) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated p-p65, p-AKT, AKT, p-p38, p38, p-ERK, ERK, p-JNK, JNK and GAPDH at 30 min after infection. (b) IL-6 and IL-23 concentrations were quantified by ELISA in supernatants at 12 h. (c) Il7a expression was evaluated by real-time PCR at 18 h and IL-17 concentrations in supernatants were quantified at 24 h. All gene quantities were normalized to the expression of the reference gene β-actin. (d) Expression of intracellular IL-17 at 24 h. (e) Neutrophils were isolated from total bone marrow cells of WT, Tlr2−/− and Tlr4−/− mice, and then stimulated with Pam3CSK4, LPS or mixture of Pam3CSK4 and LPS (Mix). IL-6 and IL-23 concentrations were quantified by ELISA in supernatants at 12 h. (f) Il7a expression was evaluated by PCR in WT neutrophils after stimulated with Pam3CSK4, LPS or mixture of Pam3CSK4 and LPS. Data shown are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

To further assess the roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in IL-6, IL-23, and IL-17 production in neutrophils, we used Pam3CSK4 and LPS to activate TLR2 and TLR4 in neutrophils. First, we assessed the expression of IL-6 and IL-23 by ELISA, and found that IL-6 and IL-23 expression levels increased markedly in WT neutrophils after Pam3CSK4 and LPS treatment (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, Il17a mRNA was detected in WT neutrophils after Pam3CSK4 and LPS treatment (Fig. 4f). These results showed that TLR2/TLR4, which regulates various downstream signaling pathways, played a major role in MTB H37Rv-induced IL-6 and IL-23 production in neutrophils.

3.5. Human Neutrophils Produced IL-17 Via Autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 After MTB H37Rv Infection

To ascertain the role of autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 in inducing IL-17 production in human neutrophils after MTB H37Rv infection, we isolated a highly purified population of human peripheral blood neutrophils by gradient centrifugation and infected with MTB H37Rv. We detected IL-6 and IL-23 in neutrophils (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, intracellular IL-17 was detected in about 20% of the total neutrophil population (Fig. 5b). Next, we detected Il17a expression in neutrophils, and found that its expression was inhibited in the presence of anti-IL-6 or anti-IL-23 but not in the presence of anti-IL-1β or anti-TGF-β (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Expression of IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 in human peripheral blood neutrophils. (a–e) Neutrophils were isolated from human peripheral blood, and then infected with MTB H37Rv. The uninfected neutrophils were as control group. (a) Il6 and Il23mRNA expression for indicated time points determined by real-time PCR. All gene quantities were normalized to the expression of the reference gene gapdh. (b) Intracellular IL-17 identified by Flow cytometry. (c) Il17a expression plus no antibody (-) or neutralizing antibody (Ab) to IL-1β, TGF-β, IL-6 or IL-23. GAPDH (housekeeping gene) serves as a loading control throughout. (d–e) IL-6, IL-23 (d) and IL-17 (e) concentrations in supernatants were quantified by ELISA after treated with NF-κB-inhibitor JSH-23 (20 μM), PI3K- inhibitor LY294002 (30 μM), MEK1/2-inhibitor U0126 (40 μM), p38 inhibitor-SB203580 (10 μM) or JNK-inhibitor SP600125 (20 μM). (f–g) Neutrophils were isolated from human peripheral blood, and then stimulated with Pam3CSK4, LPS or mixture of Pam3CSK4 and LPS. The unstimulated human neutrophils were as control group (Ctrl). (f) IL-6 and IL-23 concentrations in supernatants were quantified. (g) Intracellular IL-17 identified by Flow cytometry. Data shown in are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

To evaluate the role of signaling pathways and TLRs in IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 production by human neutrophils, inhibitors or agonists were used. Similar to mouse neutrophils, IL-6 production was inhibited by JSH-23, SB203580 and SP600125, IL-23 production was inhibited by JSH-23 and U0126 (Fig. 5d), and IL-17 production was inhibited by the above-mentioned inhibitors (Fig. 5e). IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17 were detected in human neutrophils after LPS and Pam3CSK4 treatment (Fig. 5f, g). Together, these findings demonstrated that similar to mouse neutrophils, autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 induced IL-17 expression in neutrophils after MTB H37Rv infection via TLR2 and TLR4- activated signaling pathways.

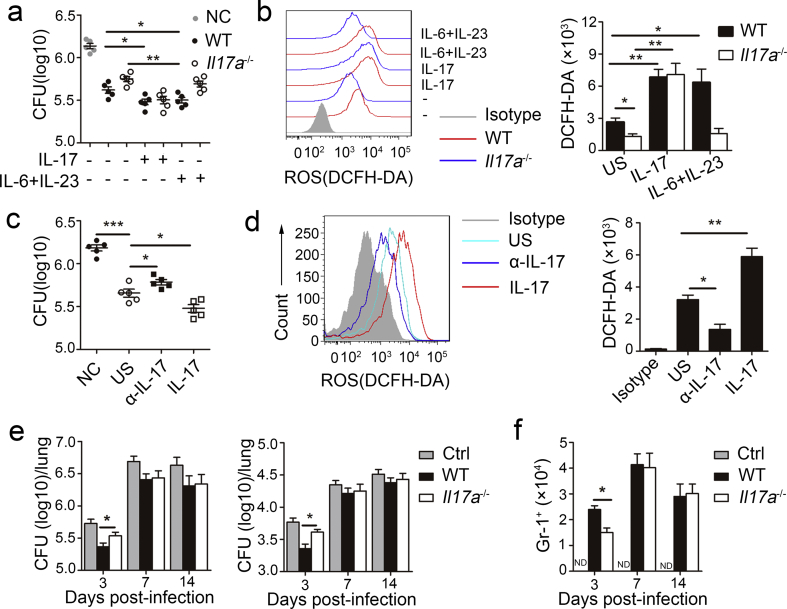

3.6. IL-17 Production by Neutrophils Inhibited MTB H37Rv Growth

IL-17 is an important cytokine not only in early neutrophils recruitment but also in the release of cytotoxic mediators that enhance neutrophils antibacteria activity (Mantovani et al., 2011). To determine if autocrine IL-17 regulates neutrophil antibacterial ability in vitro, we infected neutrophils from the bone marrow of WT or Il17a−/− mice with MTB H37Rv and then assessed viable bacilli based on colony-forming units (CFUs). We found that WT neutrophils exhibited potent killing activity, and the activity was further enhanced by recombinant mouse IL-17 or a combination of IL-6 and IL-23 (Fig. 6A). Conversely, compared to WT neutrophils, Il17a−/− neutrophils exhibited impaired killing activity, which was recovered by IL-17, but not by a combination of IL-6 and IL-23 (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Role of IL-17 from neutrophils in regulating MTB H37Rv growth. (a–b) MTB H37Rv infected neutrophils from WT and Il17a−/− mice treated with (+) or without (−) recombinant mouse IL-17 or combination of IL-6 and IL-23. (a) MTB H37Rv viability was evaluated though CFU. CFU for each data point were calculated as the average count from four plates at two different dilutions. (b) ROS productions were assessed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of intracellular DCFH-DA at 18 h. (c–d) MTB H37Rv infected human neutrophils treated with (+) or without (−) anti-IL-17 (α-IL-17) or recombinant human IL-17. (c) MTB H37Rv viability was evaluated though CFU. (d) ROS productions were assessed. (e–f) Cd18−/− mice were infected with MTB H37Rv, and then were given no neutrophils (Ctrl) or given intravenous injection of 2 × 106 WT or Il17a−/− bone marrow neutrophils every two days. (e) CFU in the lungs and spleens were determined on days 3, 7, and 14 after infection. (f) Total infiltrated Gr-1+ neutrophils in the lung. Data shown in are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

The production of ROS by neutrophils limits the growth of MTB (Yang et al., 2012) and autocrine IL-17 in neutrophils enhances ROS production in fungal infections (Taylor et al., 2014), accordingly, we examined if the role of IL-17 in MTB killing depends on ROS production. We assessed ROS production by measuring intracellular 2,7-dichlorodi-hydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), and found lower ROS production by neutrophils from Il17a−/− mice than by neutrophils obtained from WT mice (Fig. 6b). ROS production in WT neutrophils was further increased after further stimulation with IL-17 or a combination of IL-6 and IL-23 (Fig. 6b). However, ROS production was only increased after further stimulation with IL-17, but not by the combination of IL-6 and IL-23 in Il17a−/− neutrophils (Fig. 6b).

Human peripheral blood neutrophils have a similar phenotype to that of mouse neutrophils, after treatment with an antibody against IL-17 (α-IL-17), antibacterial activity was inhibited (Fig. 6c) and ROS production was decreased (Fig. 6d); in contrast, antibacterial activity was enhanced (Fig. 6c) and ROS production was increased after stimulation with IL-17 (Fig. 6d).

Because β2 integrin chain CD18-deficient (Cd18−/−) neutrophils cannot migrate into infected tissues (Ding et al., 1999), to determine if IL-17-producing neutrophils regulate MTB growth in vivo, we used an adoptive-transfer model in which donor WT or Il17a−/− neutrophils are injected intravenously into recipient Cd18−/− mice with MTB H37Rv infection. We found that there were significantly fewer viable bacilli (Fig. 6e), but a greater number of total infiltrated neutrophils (Fig. 6f) in the lung of Cd18−/− mice administered WT neutrophils than in mice administered Il17a−/− neutrophils at the early phase of infection. However, the amount of viable bacilli and number of infiltrated neutrophils were not different on days 7 or 14 after infection. Overall, these data indicated that autocrine IL-17 in neutrophils inhibited MTB growth by mediating ROS production and their own migration at the early phase of infection.

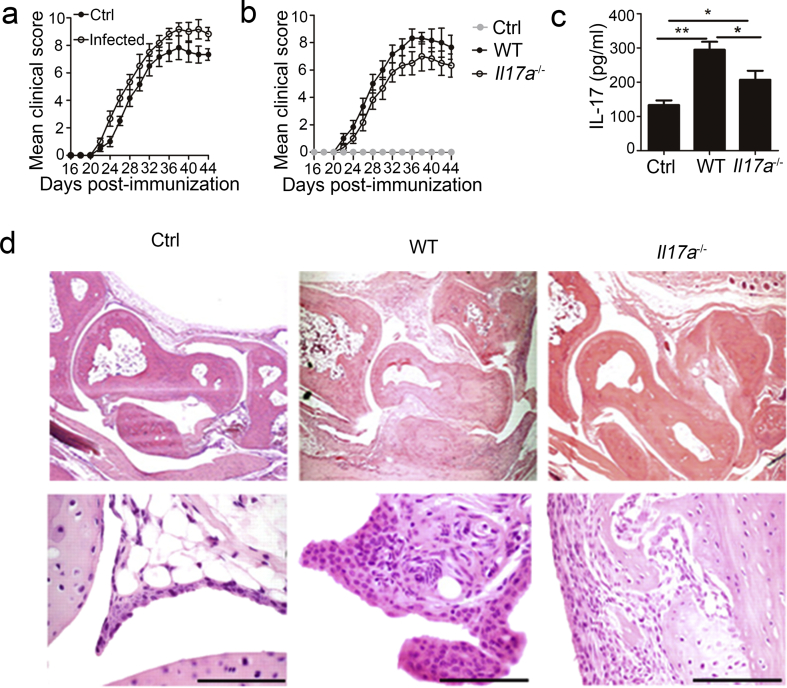

3.7. MTB H37Rv-induced IL-17 Production in Neutrophils Promoted CIA Development

Because MTB infection and IL-17 production in neutrophils is associated with both RA and CIA (Shen et al., 2015, Kanagawa et al., 2015, Pope and Shahrara, 2013), we assessed the role of MTB H37Rv-induced IL-17 production by neutrophils in CIA. First, we confirmed that mice infected with MTB H37Rv showed a significantly elevated CIA arthritis incidence (Table 1) and clinical scores (Fig. 7a) compared to those of uninfected mice. An adoptive-transfer model was used to determine if MTB- induced-IL-17 production in neutrophils contributes to CIA. We observed a significantly lower incidence (Table 2) and lower clinical scores (Fig. 7b) in MTB H37Rv-infected Cd18−/− mice given Il17a−/− neutrophils relative to that given WT neutrophils. Additionally, we found that serum from Cd18−/− mice given Il17a−/− neutrophils had lower IL-17 concentrations than those given WT neutrophils (Fig. 7c). Previous studies have shown that IL-17 has regulatory effects on the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in mice with CIA, such as IL-6, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β and receptor activator for nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) (Atkinson et al., 2016, Bai et al., 2014). We analyzed the role by IL-17 production of neutrophils in the expression of these target genes in mice with CIA exhibiting severe arthritis. Our results showed that cartilage tissue from Cd18−/− mice given Il17a−/− neutrophils had lower expression levels of these pro-inflammatory cytokines than those of tissues from mice given WT neutrophils (Supplementary Fig. 4). Inflamed joints from Cd18−/− mice given WT neutrophils were extensively infiltrated by inflammatory cells and showed regions of bone and cartilage destruction (Fig. 7d). These results suggested that MTB H37Rv-induced IL-17 production in neutrophils contributed to CIA development.

Table 1.

Clinical CIA data in WT C57BL/6 J mice uninfected (Ctrl) or infected with MTB H37Rv.

| Group | Day of onsetc | Incidencea | Maximum scoreb, c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | 23.7 ± 0.8 | 50.0% (5/10) | 8.6 ± 0.6 |

| Infected | 22.3 ± 0.3 | 70.0% (7/10) | 9.8 ± 0.5 |

CIA incidence (arthritic/total mice) at day 44 is shown.

The mean value of maximum clinical scores of every mice.

Mean ± S.E.M. of diseased mice.

Fig. 7.

Role of IL-17 from neutrophils in development of CIA during MTB H37Rv infection. (a) CIA was induced in 6-week-old WT mice infected with or without MTB H37Rv and arthritis scores of diseased mice were evaluated. (b–d) CIA was induced in Cd18−/− mice infected with MTB H37Rv, and then were given no neutrophils (Ctrl) or given intravenous injection of 2 × 106 WT or Il17a−/− bone marrow neutrophils every two days. (b) Arthritis scores of diseased mice were evaluated. (c) Concentrations of IL-17 in serum were quantified. (d) Histologic sections of arthritic joint from the CIA mice with severe arthritis stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Scale bars: 1 mm. Data shown in are the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results.

Table 2.

Clinical CIA data in MTB H37Rv-infected Cd18−/− mice adopted WT neutrophils or Il17a−/− neutrophils.

| Group | Day of onsetc | Incidencea | Maximum scoreb, c |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT neutrophils | 22.7 ± 0.4 | 45% (9/20) | 9.2 ± 0.7 |

| Il17a−/− neutrophils | 24.0 ± 0.7 | 30% (6/20) | 7.8 ± 1.0 |

CIA incidence (arthritic/total mice) at day 44 is shown.

The mean value of maximum clinical scores of every mice.

Mean ± S.E.M. of diseased mice.

4. Discussion

IL-17 is a proinflammatory cytokine and is mainly secreted by CD4+ T, γδ T, and innate lymphoid cells as well as neutrophils. Previous reports have indicated that neutrophils are the main source of IL-17 in patients with fungal keratitis (Karthikeyan et al., 2011) diverse mouse models, including lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation (Ferretti et al., 2003), systemic histoplasmosis (Wu et al., 2013), acute kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury (Li et al., 2010), inhalation anthrax (Garraud et al., 2012) and early-stage arthritis (Katayama et al., 2013). Though IL-17 expression was not detected in neutrophils from M. bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin infected mice (Umemura et al., 2007), in this study, we demonstrated that MTB H37Rv induced IL-17 production in neutrophils (Gr-1+) and this effect was dependent on paracrine and autocrine IL-6 and IL-23.

Our results supported those of previous studies indicating that IL-6 and IL-23 are essential for the expression of the gene encoding IL-17 in mouse and human neutrophils (Taylor et al., 2014). However, we demonstrated that neutrophil expression of IL-6 and IL-23 was also induced by MTB H37Rv, and autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 were sufficient to influence IL-17 production by themselves in neutrophils. IL-6 production by neutrophils has been linked to protection against mycobacterial infection (Morris et al., 2013), but it is not clear whether neutrophils express IL-23 after MTB H37Rv infection. IL-23 is produced by innate immune cells, especially dendritic cells (Langrish et al., 2004), but studies have confirmed that neutrophil expression of IL-23 is induced by Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein (D'Elios et al., 2007), and tissue-infiltrating neutrophils represent the main source of IL-23 in the colon of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (Kvedaraite et al., 2016). In this study, we detected Il23 mRNA and IL-23 protein in neutrophils infected with H37Rv. The IL-23 concentration decreased in the serum from MTB H37Rv-infected mice after the depletion of neutrophils.

Activation of proinflammatory pathways, including NF-κB, PI3K-AKT, p38, JNK, and ERK, initiates the production of cytokines in innate immune cells, such as macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2004). It was previously reported that the activation of p38 and NF-κB mediates IL-6 production in neutrophils stimulated with LPS (Ajibade et al., 2012). However, we found that JNK also plays a critical role in activating the production of IL-6 except p38 and NF-κB, but AKT or ERK no effect. Consistent with these findings, previous studies have shown that Brucella abortus rBCSP31 induced IL-6 production in macrophages via the activation of p38, JNK, and NF-κB (Li et al., 2014). Though neutrophils are able to express IL-23, the regulatory signaling pathways remain unclear. Previous studies have demonstrated that ERK activation is required for LPS-induced-IL-23 production in dendritic cells (Brereton et al., 2009) and HBV viral protein HBx-induced IL-23 expression in hepatitis B virus infection (Cho et al., 2014). We demonstrated that the suppression of the phosphorylation of ERK and NF-κB decreases IL-23 production in neutrophils infected with MTB H37Rv, but AKT, p38, and JNK had no effect. However, distinct signaling pathways appear to be required for IL-23 production, which is positively regulated by PI3K and ERK, but negatively regulated by p38 MAPK in THP-1 cells infected with T. gondii RH strain (Quan et al., 2015). These results indicate that IL-23 production is regulated by distinct signaling pathways in a cell type-specific manner.

Pattern recognition receptors of the innate immune system, especially TLR2 and TLR4, are critical for the recognition of MTB components and activation of proinflammatory pathways. TLR2 and TLR4 activate a common signaling pathway that results in the activation of NF-κB, ERK, p38 and JNK (Akira et al., 2006). We investigated if TLR2 and TLR4, upstream pathways of NF-κB, ERK, p38, and JNK, are involved in the production of IL-6, IL-23, and IL-17 in MTB H37Rv-infected neutrophils. We found that TLR2 or TLR4 deficiency suppressed the phosphorylation of NF-κB, ERK, p38, and JNK and negatively regulated IL-6 and IL-23 synthesis in MTB H37Rv-infected neutrophils. In contrast, IL-6 and IL-23 production increased in response to Pam3CSK4 and LPS, agonists of TLR2 and TLR4. Taken together, levels of IL-6 and IL-23 in neutrophils were differentially regulated by the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways downstream of TLR2/4 signaling.

IL-17 is an important proinflammatory cytokine not only in early neutrophil recruitment, but also in the release of cytotoxic mediators to enhance neutrophil antibacterial activity. However, data are equivocal with regard to whether IL-17 is required for protection against MTB; some, but not all studies suggest that it is required for the control of bacteria (Torrado and Cooper, 2010). In the present study, we evaluated the effect of IL-17 production by neutrophils on antibacterial activity in vitro. Neutrophils produced and used IL-17 in an autocrine manner to enhance ROS production and antibacterial activity. Consistent with these findings, autocrine activity of IL-17 induced the production of ROS and increased fungal killing (Taylor et al., 2014). Furthermore, we demonstrated that IL-17 production by neutrophils played a key role in neutrophil induction and antibacterial activity in the early phase in vivo using an adoptive-transfer model. Overall, our results indicate that IL-17 is required for the control of bacteria at the early phase of infection. Neutrophils function as phagocytic cells that mediate host defense by recognizing and destroying foreign infectious pathogens (Geissmann et al., 2010). However, neutrophils are less well studied than other components of the host response to MTB infection and previous results are controversial (Martineau et al., 2007, Lowe et al., 2012, Borregaard, 2010). In this study, our data showed that a larger number of neutrophils were correlated with fewer viable bacilli at the early stage of MTB infection. Accordingly, neutrophils may play a role in MTB killing at the early stage of MTB infection.

IL-17 and neutrophils are both required for the control of bacteria, but they are unfortunately closely related to the occurrence and development of many autoimmune diseases, including RA (Abdollahi-Roodsaz et al., 2008). Surprisingly, MTB infection is also capable of promoting the development of RA, but the mechanism remains unclear. It has previously been reported that neutrophils are an essential source of IL-17 in the effector phase of arthritis (Katayama et al., 2013). In this study, we also assessed the role of MTB-induced IL-17 production by neutrophils in CIA. Our results showed that the CIA arthritis incidence and clinical scores were elevated in MTB-infected mice. Furthermore, Cd18−/− mice given IL-17−/− neutrophils had a significantly lower incidence and clinical scores relative to those of mice given WT neutrophils. MTB-induced IL-17 in neutrophils may play a vital role in the development of RA.

In conclusion, we found that neutrophils are able to express IL-17, and this expression was dependent on autocrine IL-6 and IL-23 during MTB infection. MTB-induced IL-17 production in neutrophils increased MTB killing activity, but promoted arthritis severity in a CIA model. These results demonstrate an anti-mycobacterial mechanism and a pathogenic role of MTB in arthritis development. They could therefore have important implications for the development of therapies for MTB infection-associated diseases, including tuberculosis and autoimmune diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Li Ma, Shengfeng Hu. Performed the experiments: Shengfeng Hu, Wenting He, Xialin Du, Jiahui Yang. Analyzed the data: Li Ma, Shengfeng Hu, Xiao-Ping Zhong. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: Qian Wen. Wrote the paper: Li Ma, Shengfeng Hu, Xiao-Ping Zhong. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571951, 81371764, 81641062), National Science and Technology Key Projects on Major Infectious Diseases (2017ZX10201301-008), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2016A030311001), Science and Technology Project of Guangdong Province (2017A020212007), Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou (201707010215), the Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2012).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.08.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Abdollahi-Roodsaz S., Joosten L.A., Koenders M.I., Devesa I., Roelofs M.F., Radstake T.R., Heuvelmans-Jacobs M., Akira S., Nicklin M.J., Ribeiro-Dias F., Van Den Berg W.B. Stimulation of TLR2 and TLR4 differentially skews the balance of T cells in a mouse model of arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:205–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI32639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajibade A.A., Wang Q., Cui J., Zou J., Xia X., Wang M., Tong Y., Hui W., Liu D., Su B., Wang H.Y., Wang R.F. TAK1 negatively regulates NF-kappaB and p38 MAP kinase activation in Gr-1 + CD11b + neutrophils. Immunity. 2012;36:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S., Uematsu S., Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amulic B., Cazalet C., Hayes G.L., Metzler K.D., Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:459–489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson S.M., Hoffmann U., Hamann A., Bach E., Danneskiold-Samsoe N.B., Kristiansen K., Serikawa K., Fox B., Kruse K., Haase C., Skov S., Nansen A. Depletion of regulatory T cells leads to an exacerbation of delayed-type hypersensitivity arthritis in C57BL/6 mice that can be counteracted by IL-17 blockade. Dis. Model. Mech. 2016;9:427–440. doi: 10.1242/dmm.022905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F., Tian H., Niu Z., Liu M., Ren G., Yu, Y., Sun, T., Li, S. & Li, D. Chimeric anti-IL-17 full-length monoclonal antibody is a novel potential candidate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014;33:711–721. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardoel B.W., Kenny E.F., Sollberger G., Zychlinsky A. The balancing act of neutrophils. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:526–536. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borregaard N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity. 2010;33:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand D.D., Latham K.A., Rosloniec E.F. Collagen-induced arthritis. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brereton C.F., Sutton C.E., Lalor S.J., Lavelle E.C., Mills K.H. Inhibition of ERK MAPK suppresses IL-23- and IL-1-driven IL-17 production and attenuates autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 2009;183:1715–1723. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H.K., Kim S.Y., Yoo S.K., Choi Y.H., Cheong J. Fatty acids increase hepatitis B virus X protein stabilization and HBx-induced inflammatory gene expression. FEBS J. 2014;281:2228–2239. doi: 10.1111/febs.12776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A.M. Cell-mediated immune responses in tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:393–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cua D.J., Tato C.M. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:479–489. doi: 10.1038/nri2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley J.M., Thomay A.A., Connolly M.D., Reichner J.S., Albina J.E. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Elios M.M., Amedei A., Cappon A., Del Prete G., De Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori (HP-NAP) as an immune modulating agent. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2007;50:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z.M., Babensee J.E., Simon S.I., Lu H., Perrard J.L., Bullard D.C., Dai X.Y., Bromley S.K., Dustin M.L., Entman M.L., Smith C.W., Ballantyne C.M. Relative contribution of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to neutrophil adhesion and migration. J. Immunol. 1999;163:5029–5038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorhoi A., Reece S.T., Kaufmann S.H. For better or for worse: the immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis balances pathology and protection. Immunol. Rev. 2011;240:235–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eum S.Y., Kong J.H., Hong M.S., Lee Y.J., Kim J.H., Hwang S.H., Cho S.N., Via L.E., Barry C.E., 3RD Neutrophils are the predominant infected phagocytic cells in the airways of patients with active pulmonary TB. Chest. 2010;137:122–128. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti S., Bonneau O., Dubois G.R., Jones C.E., Trifilieff A. IL-17, produced by lymphocytes and neutrophils, is necessary for lipopolysaccharide-induced airway neutrophilia: IL-15 as a possible trigger. J. Immunol. 2003;170:2106–2112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso Y.D., Adoni T., Anacleto A., Brooks J.B., Carvalho Mde J., Claudino R., Damasceno A., Ferreira M.L., Gama P.D., Goncalves M.V., Grzesiuk A.K., Matta A.P., Parolin M.F. How do we manage and treat a patient with multiple sclerosis at risk of tuberculosis? Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2014;14:1251–1260. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2014.962517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraud K., Cleret A., Mathieu J., Fiole D., Gauthier Y., Quesnel-Hellmann A., Tournier J.N. Differential role of the interleukin-17 axis and neutrophils in resolution of inhalational anthrax. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:131–142. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05988-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F., Manz M.G., Jung S., Sieweke M.H., Merad M., Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino A., Nagao T., Nagi-Miura N., Ohno N., Yasuhara M., Yamamoto K., Nakayama T., Suzuki K. MPO-ANCA induces IL-17 production by activated neutrophils in vitro via classical complement pathway-dependent manner. J. Autoimmun. 2008;31:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isailovic N., Daigo K., Mantovani A., Selmi C. Interleukin-17 and innate immunity in infections and chronic inflammation. J. Autoimmun. 2015;60:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakura Y., Ishigame H., Saijo S., Nakae S. Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity. 2011;34:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A., Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:987–995. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagawa H., Niki Y., Kobayashi T., Sato Y., Katsuyama E., Fujie A., Hao W., Miyamoto K., Tando T., Watanabe R., Morita M., Morioka H., Matsumoto M., Toyama Y., Miyamoto T. Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes arthritis development through Toll-like receptor 2. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2015;33:135–141. doi: 10.1007/s00774-014-0575-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan R.S., Leal S.M., Jr., Prajna N.V., Dharmalingam K., Geiser D.M., Pearlman E., Lalitha P. Expression of innate and adaptive immune mediators in human corneal tissue infected with Aspergillus or Fusarium. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:942–950. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama M., Ohmura K., Yukawa N., Terao C., Hashimoto M., Yoshifuji H., Kawabata D., Fujii T., Iwakura Y., Mimori T. Neutrophils are essential as a source of IL-17 in the effector phase of arthritis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T., Bettelli E., Oukka M., Kuchroo V.K. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvedaraite E., Lourda M., Idestrom M., Chen P., Olsson-Akefeldt S., Forkel M., Gavhed D., Lindforss U., Mjosberg J., Henter J.I., Svensson M. Tissue-infiltrating neutrophils represent the main source of IL-23 in the colon of patients with IBD. Gut. 2016;65:1632–1641. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-309014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langrish C.L., McKenzie B.S., Wilson N.J., De Waal Malefyt R., Kastelein R.A., Cua D.J. IL-12 and IL-23: master regulators of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2004;202:96–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner T.R., Borel S., Gutierrez M.G. The innate immune response in human tuberculosis. Cell. Microbiol. 2015;17:1277–1285. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Huang L., Vergis A.L., Ye H., Bajwa A., Narayan V., Strieter R.M., Rosin D.L., Okusa M.D. IL-17 produced by neutrophils regulates IFN-gamma-mediated neutrophil migration in mouse kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:331–342. doi: 10.1172/JCI38702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.Y., Liu Y., Gao X.X., Gao X., Cai H. TLR2 and TLR4 signaling pathways are required for recombinant Brucella abortus BCSP31-induced cytokine production, functional upregulation of mouse macrophages, and the Th1 immune response in vivo and in vitro. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2014;11:477–494. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A.M., Rubin C.J., Khandpur R., Wang J.Y., Riblett M., Yalavarthi S., Villanueva E.C., Shah P., Kaplan M.J., Bruce A.T. Mast cells and neutrophils release IL-17 through extracellular trap formation in psoriasis. J. Immunol. 2011;187:490–500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe D.M., Redford P.S., Wilkinson R.J., O'garra A., Martineau A.R. Neutrophils in tuberculosis: friend or foe? Trends Immunol. 2012;33:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani A., Cassatella M.A., Costantini C., Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:519–531. doi: 10.1038/nri3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martineau A.R., Newton S.M., Wilkinson K.A., Kampmann B., Hall B.M., Nawroly N., Packe G.E., Davidson R.N., Griffiths C.J., Wilkinson R.J. Neutrophil-mediated innate immune resistance to mycobacteria. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1988–1994. doi: 10.1172/JCI31097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris D., Nguyen T., Kim J., Kassissa C., Khurasany M., Luong J., Kasko S., Pandya S., Chu M., Chi P.T., Ly J., Lagman M., Venketaraman V. An elucidation of neutrophil functions against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013;2013:959650. doi: 10.1155/2013/959650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope R.M., Shahrara S. Possible roles of IL-12-family cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2013;9:252–256. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan J.H., Chu J.Q., Kwon J., Choi I.W., Ismail H.A., Zhou W., Cha G.H., Zhou Y., Yuk J.M., Jo E.K., Lee Y.H. Intracellular networks of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways for regulating toxoplasma gondii-induced IL-23 and IL-12 production in human THP-1 cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen T.C., Lin C.L., Wei C.C., Chen C.H., Tu C.Y., Hsia T.C., Shih C.M., Hsu W.H., Chung C.J., Sung F.C., Kao C.H. Previous history of tuberculosis is associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2015;19:1401–1405. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia J.K., Georgieva M., Rengarajan J. Innate immune defenses in human tuberculosis: an overview of the interactions between Mycobacterium tuberculosis and innate immune cells. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:747543. doi: 10.1155/2015/747543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., Ray S., Kaur M., Gupta V., Kumar H., Talapatra P., Mathur R., Arya S., Ghangas N. Exacerbation of latent lupus: is the culprit acid-fast bacilli or antitubercular therapy? Clin. Rheumatol. 2013;32:1233–1236. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P.R., Roy S., Leal S.M., Jr., Sun Y., Howell S.J., Cobb B.A., Li X., Pearlman E. Activation of neutrophils by autocrine IL-17A-IL-17RC interactions during fungal infection is regulated by IL-6, IL-23, RORgammat and dectin-2. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:143–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrado E., Cooper A.M. IL-17 and Th17 cells in tuberculosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umemura M., Yahagi A., Hamada S., Begum M.D., Watanabe H., Kawakami K., Suda T., Sudo K., Nakae S., Iwakura Y., Matsuzaki G. IL-17-mediated regulation of innate and acquired immune response against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. J. Immunol. 2007;178:3786–3796. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S.Y., Yu J.S., Liu F.T., Miaw S.C., Wu-Hsieh B.A. Galectin-3 negatively regulates dendritic cell production of IL-23/IL-17-axis cytokines in infection by Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Immunol. 2013;190:3427–3437. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.T., Cambier C.J., Davis J.M., Hall C.J., Crosier P.S., Ramakrishnan L. Neutrophils exert protection in the early tuberculous granuloma by oxidative killing of mycobacteria phagocytosed from infected macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material