Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress is one of the key components of the pathology of various neurodegenerative disorders. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons owing to the aggregation of alpha-synuclein (αS) in the brain. A number of polyphenols have been reported to inhibit the αS aggregation resulting in the possible prevention of PD. The involvement of free radicals in mediating the neuronal death in PD has also been implicated.

Methods

In the present study, the transgenic flies expressing human αS in the brain were exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM of apigenin established in diet for 24 days.

Results

The flies showed an increase in life span, glutathione, and dopamine content. The exposure of PD flies to various doses of apigenin also results in the reduction of glutathione-S-transferase activity, lipid peroxidation, monoamine oxidase, caspase-3, and caspase-9 activity in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusion

The results of the present study reveal that apigenin is potent in increasing the life span, dopamine content, reduced the oxidative stress as well as apoptosis in transgenic Drosophila model of PD.

Keywords: apigenin, Drosophila melanogaster, oxidative stress, Parkinson’s disease

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress is one of the key components of the pathology of various neurodegenerative disorders (viz. Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s).1 Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor dysfunction as a result of the death of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain.2 Drosophila has emerged as a useful animal model for studying various human diseases.3 Its genome analysis has revealed the existence of orthologs for about 75% of human disease genes.4 The yeast-based UAS (upstream activation sequence)–GAL4 system is an efficient bipartite approach in the activation of gene expression in Drosophila.5 Using this approach, various transgenic Drosophila models (mutant as well as wild) are available for studying various human diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders.6 The available Drosophila models of PD showed various neurological symptoms such as locomotor dysfunction, sensitivity to oxidative stress, and reduced life span.7 A number of natural polyphenols have been reported to improve the PD symptoms in various animal models.3, 8, 9, 10 Although it is multifactorial, the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of PD cannot be ruled out.11 Advances have been made in uncovering the neuropathology of PD, but the treatment options are limited. A number of potential therapeutic compounds have been tested in clinical trials, but most of them have failed to show the desired results. Owing to the lack of effective therapy, there may be a dramatic increase in the frequency of PD patients in the coming decades. Recently, a number of traditionally used plant extracts have been successfully implicated in reducing the symptoms associated with neurodegenerative disorders.12 Apigenin ameliorated learning deficits and relieved memory retention in amyloid precursor protein (APP)/PS1 mice. It has been shown to not only modulate the processing of APP and prevent the Aβ deposits, but also to scavenge superoxide anions.13 The effect of apigenin was also studied in rats after contusive spinal cord injury.14 The injured rats exposed to apigenin showed the antioxidative effect of apigenin in terms of the reduction in malondialdehyde levels and increase in the level of superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase.14 Furthermore, it also affected the expression of apoptosis-related genes, i.e., Bax, BCl-2, and caspase 3, indicating its antiapoptotic role.14 In MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine)-induced Parkinsonism in mice, apigenin protected the dopaminergic neurons probably by reducing the oxidative damage, neuroinflammation, and microglial activation along the enhanced neurotrophic potential.15 Our earlier study conducted on the locomotor behavior of the transgenic Drosophila model of PD apigenin showed the loss of climbing ability.16 In this context, we decided to study the effect of apigenin on the transgenic Drosophila. Such types of preclinical investigations are helpful in identifying the promising drug candidates. In this context, Drosophila has emerged as a powerful tool (in vivo model) for carrying out such type of studies. Hence, in this context, the effect of apigenin (a flavonoid) was studied on the transgenic Drosophila expressing human alpha-synuclein (αS) under the GAL4–UAS system.

2. Methods

2.1. Fly strain

Transgenic fly lines that express wild-type human synuclein (h-αS) under UAS control in neurons “w[*];P{w[+mC] = UAS-Hsap/SNCA.F}”5B and the driver expressing GAL4 “w[*];P{w[+mC] = GAL4-elavL}”3’ were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA). When males of UAS-Hsap/SNCA.F strains were crossed with the virgin females of GAL4-elav.L (vice versa), the progeny expressed the human αS in neurons, and these flies (progeny) were referred to as PD flies.2

2.2. Drosophila culture and crosses

The flies were cultured on standard Drosophila food containing agar, corn meal, sugar, and yeast at 25 °C (24 °C ± 1 °C). Crosses were set up as described in our earlier published work.16 The PD flies were exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM of apigenin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) mixed in diet at final concentration. The PD flies were also exposed to 10−3 M l-dopamine. The UAS-Hsap/SNC.F acted as control. The control flies were also separately exposed to selected doses of apigenin. Fly heads from each group were isolated (40 heads/group; five replicates/group), and the homogenate was prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for the biochemical parameters.

2.3. Drosophila life span determination

Newly enclosed flies from the non-PD (control) and PD groups were placed in culture tubes (10 flies per tube) containing the desired concentration of apigenin. The life span was determined according to the method described by Long et al.17

2.4. Estimation of glutathione content

Glutathione (GSH) content was studied colorimetrically using Ellman’s reagent [5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB)] as per the method described by Jollow et al.18 The brain homogenate was precipitated with 4% sulfosalicyclic acid (4%) at a ratio of 1:1. The samples were kept at 4 °C for 1 hour and then subjected to centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The assay mixture consisted of 550 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer, 100 μL supernatant, and 100 μL DTNB. The Optical Density (OD) was read at 412 nm, and the results were expressed as μM of GSH/g tissue.

2.5. Estimation of glutathione-S-transferase activity

The method described by Habig et al19 was used to determine glutathione-S-transferase (GST) activity. The reaction mixture contained 500 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer, 150 μL of 10 mM 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB), 200 μL of 10 mM reduced GSH, and 50 μL of brain homogenate. The OD was read at 340 nm, and the enzyme activity was expressed as μM of CDNB conjugates/min/mg protein.

2.6. Lipid peroxidation assay

The assay was performed as described by Ohkawa et al.20 The reaction mixture was made by adding 5 μL of 10 mM butyl-hydroxytoluene, 200 μL of 0.6.7% thiobarbituric acid, 600 μL of 1% O-phosphoric acid, 105 μL distilled water, and 90 μL brain homogenate. The resultant mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 45 minutes, and the OD was measured at 535 nm. The results were expressed as nmol of Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) formed/h/g tissue.

2.7. Assay for caspase-9 (Dronc) and caspase-3 (Drice) activities

The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol with slight modifications (BioVision Inc., Milipitas, CA, USA). The assay was based on spectrophotometric detection of the chromophore p-nitroanilide (pNA) obtained after the specific action of caspase-3 and caspase-9 on tetrapeptide substrates, acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp p-nitroanilide (DEVD-pNA) and Ac-Leu-Glu-His-Asp-p-nitroanalide (LEHD-pNA), respectively. The assay mixture consisted of 50 μL brain homogenate and 50 μL chilled cell lysis buffer incubated on ice for 10 minutes. After incubation, 50 μL of 2× reaction buffer (containing 10 mM dithiothreitol) with 200 μM substrate (DEVD-pNA for Drice and IETD-pNA for Dronc) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 hours. The reaction was quantified at 405 nm.

2.8. Estimation of protein carbonyl content

The protein carbonyl content was estimated according to the protocol described by Hawkins et al.21 About 250 μL of brain homogenate was placed in Eppendorf centrifuge tubes separately. Then, 250 μL of 10 mM 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine (dissolved in 2.5 M HCl) was added, after which it was vortexed and kept in the dark for 20 minutes. Next, about 125 μL of 50% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid was added to the mixture, followed by thorough mixing and incubation at −20 °C for 15 minutes. The tubes were then centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 minutes at 9000 rpm. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet obtained was washed twice with ice-cold ethanol/ethyl acetate (1:1). Finally, the pellets were redissolved in 1 mL of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, and the absorbance was read at 370 nm.

2.9. Estimation of monoamine oxidase

The method described by McEven (1965)22 was used to estimate the monoamine oxidase (MAO) activity. The assay mixture consisted of 400 μL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4.), 1300 μL distilled water, 100 μL benzylamine hydrochloride, and 200 μL brain homogenate. The assay mixture was incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then 1 mL of 10% perchloric acid was added and centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 minutes. The OD was taken at 280 nm.

2.10. Estimation of dopamine content

The method described by Schlumpf et al23 was used to estimate the dopamine content. A total of 40 heads of PD flies were homogenized in 500 μL HCl–butanol (0.8.5 mL of 37% HCl in 1 L n-butanol). The suspension was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes. To the supernatant, 250 μL heptane and 100 μL of 0.1 M HCl were added; then it was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 minutes. The lower aqueous layer was used for the assay. The assay mixture consisted of 100 μL supernatant, 50 μL 0.4 M HCl, and 100 μL iodine solution. After incubation for 2 minutes, 100 μL sodium sulfite and 100 μL of 10 M acetic acid were added, followed by boiling at 100 °C for 6 minutes. The samples were read at 375 nm after cooling at room temperature.

3. Results

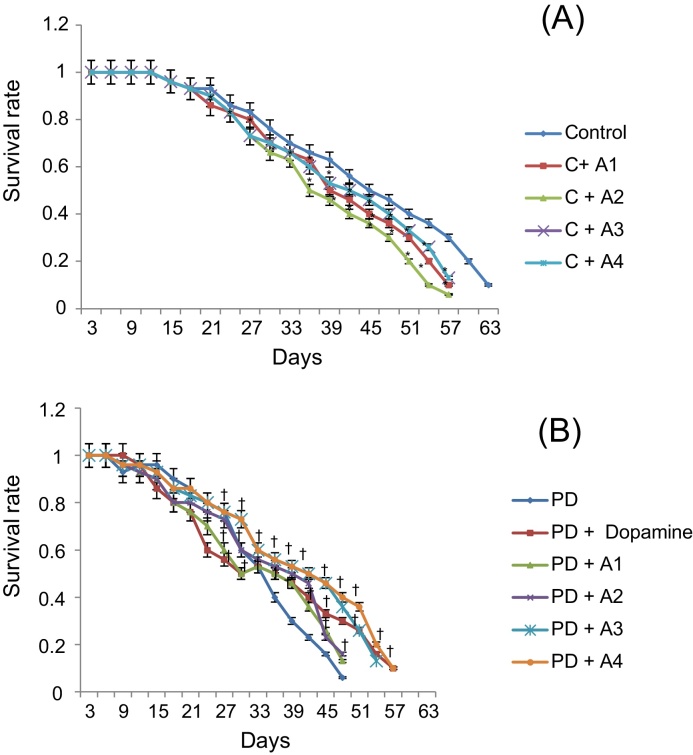

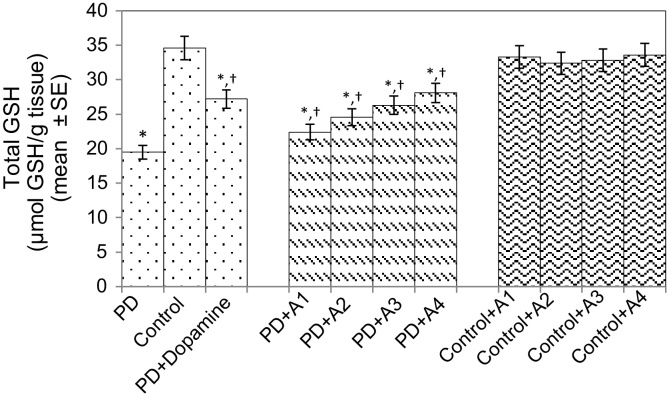

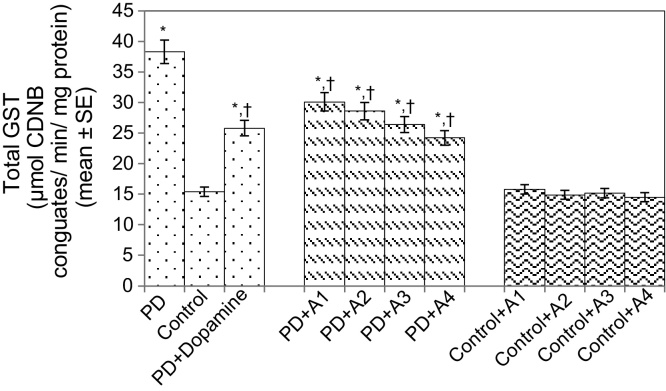

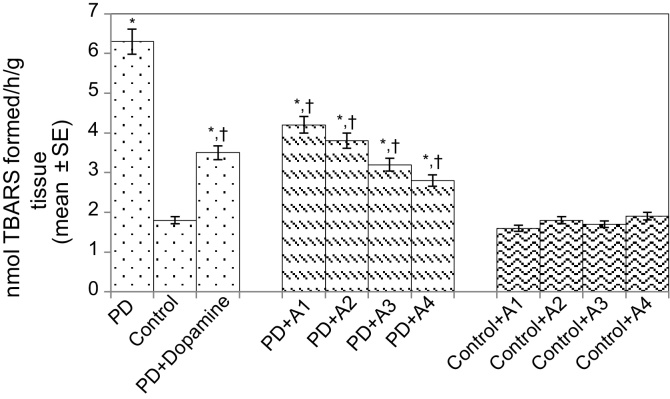

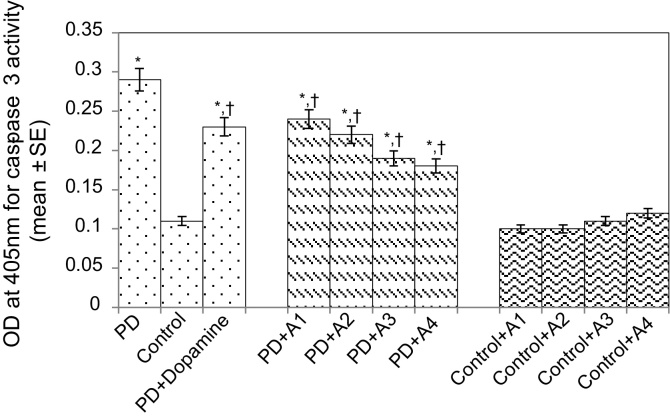

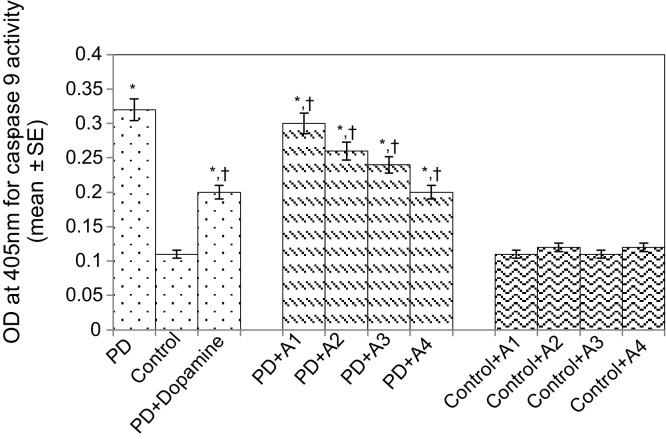

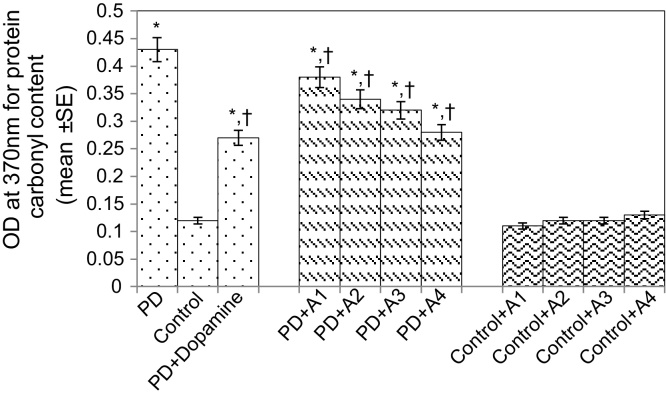

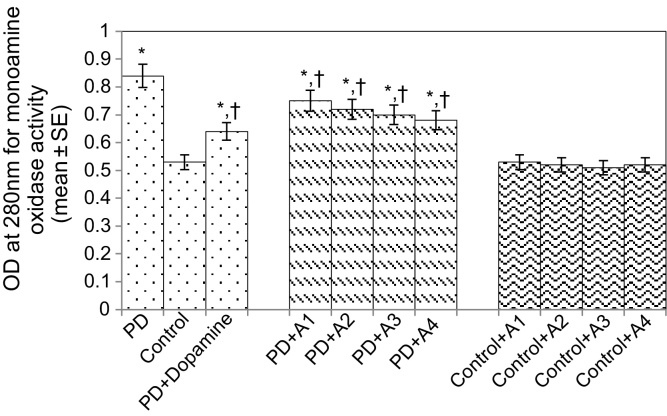

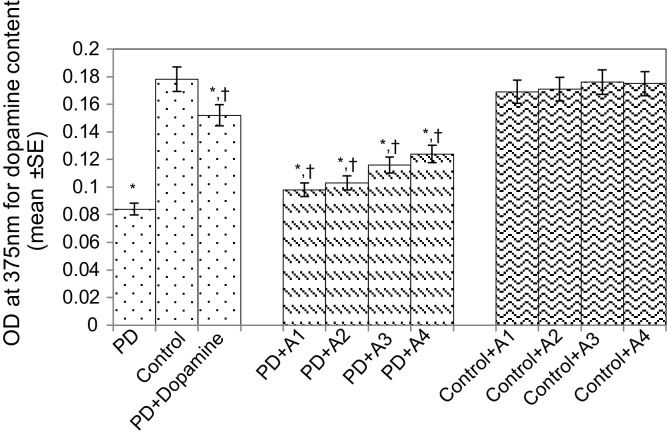

The results obtained for the survival assay are shown in Fig. 1. The exposure of PD flies to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a dose-dependent increase in the life span of flies expressing human αS (Fig. 1). The results obtained for GSH content are shown in Fig. 2. The PD flies showed a significant (1.77-fold) decrease in GSH content compared to control flies (Fig. 2; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a significant dose-dependent increase of 1.14-, 1.26-, 1.34-, and 1.44-fold, respectively (Fig. 2; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10−3 M dopamine showed a significant (1.39-fold) increase in GSH content (Fig. 2; p < 0.05). The results obtained for GST activity are shown in Fig. 3. The PD flies showed a significant (2.48-fold) increase compared to control flies (Fig. 3; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a significant dose-dependent (1.27-, 1.33-, 1.45-, and 1.58-fold, respectively) decrease compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 3; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10−3 M dopamine showed a significant (1.48-fold) decrease in GST activity compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 3; p < 0.05). The results obtained for lipid peroxidation (LPO) are shown in Fig. 4. A significant (3.5-fold) increase in LPO was observed in PD flies compared to controls (Fig. 4; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a significant (1.5-, 1.6-, 1.9-, and 2.25-fold, respectively) decrease in LPO compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 4; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10−3 M dopamine showed a 2.11-fold increase in LPO compared to control flies (Fig. 4; p < 0.05). The results obtained for the Protein carbonyl (PC) content are shown in Fig. 5. The PD flies showed a significant (3.58-fold) increase compared to control flies (Fig. 5; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a dose-dependent significant (1.13-, 1.26-, 1.34-, and 1.53-fold, respectively) decrease in PC content compared to the unexposed PD flies (Fig. 5; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10−3 M of dopamine showed a 1.59-fold decrease in the PC content compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 5; p < 0.05). The results obtained for MAO activity are shown in Fig. 6. The PD flies showed a significant 1.58-fold increase in the MAO activity compared to control flies (Fig. 6; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a significantly dose-dependent (1.12-, 1.16-, 1.20-, and 1.23-fold, respectively) decrease in the MAO activity compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 6; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10−3 M of dopamine showed a significant 1.31-fold decrease in MAO activity compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 6; p < 0.05). The results obtained for caspase-3 activity are presented in Fig. 7. The PD flies showed a 2.63-fold increase in caspase-3 activity compared to control flies (Fig. 7; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a significant dose-dependent (1.24-, 1.31-, 1.52-, and 1.61-fold) decrease in activity of caspase-3 compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 7; p < 0.05). The exposure of PD flies to 10−3 M dopamine showed a significant decrease (1.26-fold) compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 7; p < 0.05). The results obtained for the activity of caspase-9 are shown in Fig. 8. The PD flies showed a 2.90-fold increase in the activity of caspase-9 compared to control flies (Fig. 8; p < 0.05). The exposure of PD flies to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a dose-dependent significant (1.06-, 1.23-, 1.33-, and 1.60-fold, respectively) decrease compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 8; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10−3 M dopamine showed a significant (1.6-fold) decrease compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 8; p < 0.05). The results obtained for dopamine content are shown in Fig. 9. The PD flies showed a 2.11-fold decrease in dopamine content compared to control flies (Fig. 9; p < 0.05). The exposure of PD flies to 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM, and 80 μM apigenin showed a dose-dependent significant (1.16-, 1.22-, 1.38-, and 1.47-fold, respectively) increase in dopamine content compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 9; p < 0.05). The PD flies exposed to 10−3 M dopamine showed a 1.80-fold increase in dopamine content compared to unexposed PD flies (Fig. 9; p < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

(A and B) Effect of apigenin on the survival rate of PD as well as control flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays. Dopamine concentration was 10−3 M.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies[OM12] .

A, apigenin; C, control; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms.

Fig. 2.

Effect of apigenin on the glutathione (GSH) content in the brains of PD as well as control flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; Dopamine, 10−3 M; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; SE, standard error.

Fig. 3.

Effect of apigenin on the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) content in the brains of control as well as PD flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB); Dopamine, 10−3 M; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; SE, standard error.

Fig. 4.

Effect of apigenin on the lipid peroxidation in the brains of control as well as PD flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; Dopamine, 10−3 M; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms.

Fig. 5.

Effect of apigenin on the caspase-3 activity in the brains of PD as well as control flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; Dopamine, 10−3 M; OD, optical density; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; SE, standard error.

Fig. 6.

Effect of apigenin on the caspase-9 activity in the brains of PD as well as control flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; Dopamine, 10−3 M; OD, optical density; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; SE, standard error.

Fig. 7.

Effect of apigenin on the protein carbonyl content in the brains of PD as well as control flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; Dopamine, 10−3 M; OD, optical density; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; SE, standard error.

Fig. 8.

Effect of apigenin on the monoamine oxidase in the brains of control as well as PD flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM. The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; Dopamine, 10−3 M; OD, optical density; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; SE, standard error.

Fig. 9.

Effect of apigenin on the dopamine content in the brains of PD as well as control flies. A1 = 10 μM; A2 = 20 μM; A3 = 40 μM; A4 = 80 μM.The values are the mean of five assays.

*Significant at p < 0.05 compared to control.

† Significant at p < 0.05 compared to PD flies.

A, apigenin; Dopamine, 10−3 M; OD, optical density; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; SE, standard error.

4. Discussion

Besides having a number of biological activities,24, 25, 26 apigenin has also been reported to be a neuroprotective agent.14, 15, 27, 28 In our earlier study using the same strain of fly, apigenin was found to delay the loss of climbing ability.16 The ability of wild type αS to aggregate presumably explains the formation of insoluble polymers of protein known as fibrils. This fibrillar αS is the building block of Lewy bodies in association with neurofilaments and other cytoskeletal proteins.29 The formation of Lewy bodies not only results in the death of dopaminergic neurons but also increases the oxidative stress (generation of free radicals).30 Natural plant products have been reported to improve cognitive and mood disorders.31, 32 Flavonoids as well as phytoestrogens have been reported to increase the life span of Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans.33, 34, 35 Concerning oxidative, stress it is still unclear whether the degenerating neurons themselves or misfolded proteins directly result in toxicity. The degenerating neurons also produce endogenous toxins and other reactive oxygen species that may further damage normal neurons.36 The levels of these species are controlled by the antioxidant defence system.37 LPO, GSH, GST activity, PC content, and MAO are the reliable markers of oxidative stress.38 In our study, PD flies showed a decrease in GSH content, and increase in PC content, LPO, GST, and MAO activity. An increase in LPO and PC contents in the brains of human PD patients has been reported earlier.39, 40 In the present study, the exposure of PD flies to apigenin showed a dose-dependent decrease in LPO, PC content, GST, as well as MAO activity. Apigenin results in the reduction of LPO levels, PC content, and GST activity, and increase in GSH content in rats.41, 42, 43 A depletion in GSH content and an increase in GST activity have been reported in the brains of human PD patients and also in other experimental models of PD.44, 45 The reduction in oxidative stress markers attributed to apigenin is mainly due to its antioxidant property that is evident in a number of studies performed on various study models.46, 47, 48, 49

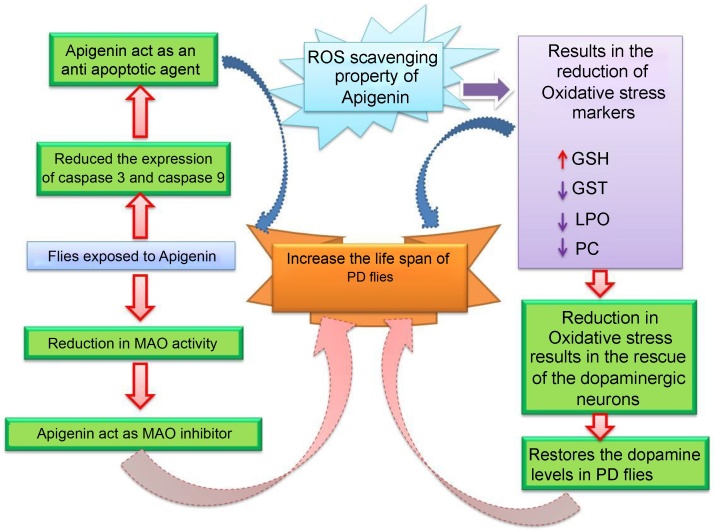

Exposure to apigenin also results in reduced levels of MAO activity in PD flies. MAOs are mitochondrial enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of monoamines in multiple tissues, including the brain. The elevated level of enzymes has been implicated in the progression of PD.50 Hence, the inhibitors of MAO may act as possible neuroprotective agents.51 MAO activity has been implicated as a contributor to oxidative neuronal damage associated with various neurodegenerative diseases.52 On the basis of the results obtained in this study, it is concluded that apigenin is also a potent inhibitor of MAO and could act as a possible therapeutic agent besides other flavonoids and phytoestrogen.50, 51, 52 The reduction in the activity of caspase-3 and -9 in PD flies exposed to apigenin is ascribed to its antiapoptotic property. This may be because of the relieving ROS accumulation/oxidative stress by apigenin.53, 54 However, some phytoestrogens have been reported to be neuroprotective by abrogating the activation of caspases cascade in rat cortical neurons.55 Hence, either the blockade of caspase activation or the antioxidative property of apigenin is responsible for conferring this neuroprotective role. The increase in the dopamine content of PD flies exposed to apigenin showed the protection of dopaminergic neurons by apigenin. A similar protection of dopaminergic neurons has been reported to be exhibited by five isoflavones isolated from Trifolium pratense.56 The antilipoperoxidant, antinecrotic, and scavenging properties of various flavonoids are well known.57 On the basis of the results obtained in this study, the possible mechanism of protection by apigenin is depicted in Fig. 10. Future therapeutic intervention that could effectively rescue the dopaminergic neurons or curtail the oxidative stress could reduce the risk of morbidity associated with PD.58 Flavonoids are the key compounds for the development of a new generation of therapeutic drugs that may prove to be clinically successful in treating neurodegenerative diseases.59

Fig. 10.

Possible mechanism involved in the protection of PD flies by apigenin based on the results obtained in our study.

GSH, glutathione; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; LPO, lipid peroxidation; MAO, monoamine oxidase; PCC: Protein carbonyl content; PD, flies exhibiting Parkinson’s disease like symptoms; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

The strain used in our study showed an age-dependent loss in dopaminergic neurons and climbing ability.2 Studies on natural plant products have shown not only an increase in dopamine content60, 61 but also reduction in oxidative stress and delay in the loss of climbing ability.61, 62 The dietary antioxidants or herbal extracts can significantly modulate the complex mechanisms of neurodegeneration and hence can contribute in the management of neurological disorders.1 Recent epidemiological studies have also revealed the promising role of some nutrients in reducing the risk of PD.63 The bioavailability of apigenin is poorly understood, and little is known about its absorption and metabolism.64 Studies in rats and CaCo-2 cells suggest that it is rapidly absorbed and extensively metabolized. 65 The health benefits of polyphenols are linked to their capacity to directly scavenge free radicals and other nitrogen species.66, 67 The neurobehavioral actions of isoflavonoids are largely antiestrogenic, and investigations in this area are still to be explored.68

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The grant (No. 59/58/2011/BMS-TRM) received from Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, to the author is gratefully acknowledged. The flies for the experiments were purchased from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Centre, Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA.

References

- 1.Aruoma O.I., Bahorun T., Jen L.S. Neuroprotection by bioactive components in medicinal and food plant extracts. Mutat Res. 2003;544:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feany M.B., Bender W.W. A Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2000;404:394–398. doi: 10.1038/35006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee S., Bang S.M., Lee J.W., Cho K.S. Evaluation of traditional medicines for neurodegenerative diseases using Drosophila models. Evid Base Complement Altern Med. 2014;2014:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2014/967462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitworth A.J., Wes P.D., Pallanck L.J. Drosophila models pioneer a new approach to drug discovery for Parkinson's disease. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03693-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy J.B. GAL4 system in Drosophila: a fly geneticist's Swiss army knife. Genesis. 2002;34:1–15. doi: 10.1002/gene.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaltiel-Karyo R., Davidi D., Menuchin Y., Frenkel-Pinter M., Marcus-Kalish M., Ringo J. A novel, sensitive assay for behavioral defects in Parkinson's disease model Drosophila. Parkinson’s Dis. 2012;2012:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2012/697564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddique Y.H., Mujtaba S.F., Jyoti S., Naz F. GC-MS analysis of Eucalyptus citriodora leaf extract and its role on the dietary supplementation in transgenic Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;55:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prasad S.N., Muralidhara Neuroprotective effect of geraniol and curcumin in an acrylamide model of neurotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster: relevance to neuropathy. J Insect Phys. 2014;60:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng X., Munishkina L.A., Fink A.L., Uversky V.N. Effects of various flavonoids on the α-synuclein fibrillation process. Parkinsons Dis. 2010;2010:1–16. doi: 10.4061/2010/650794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachdeva A.K., Chopra K. Lycopene abrogates Aβ (1–42)-mediated neuroinflammatory cascade in an experimental model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2015;26:736–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppula S., Kumar H., More S.V., Lim H.W., Hong S.M., Choi D.K. Recent updates in redox regulation and free radical scavenging effects by herbal products in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Molecules. 2012;17:11391–11420. doi: 10.3390/molecules171011391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckert G.P. Traditional used plants against cognitive decline and Alzheimer disease. Front Pharmacol. 2010;1:138. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2010.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao L., Wang J.L., Liu R., Li X.X., Li J.F., Zhang L. Neuroprotective, anti-amyloidogenic and neurotrophic effects of apigenin in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Molecules. 2013;18:9949–9965. doi: 10.3390/molecules18089949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F., Li F., Chen G. Neuroprotective effect of apigenin in rats after contusive spinal cord injury. Neurol Sci. 2014;35:583–588. doi: 10.1007/s10072-013-1566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patil S.P., Jain P.D., Sancheti J.S., Ghumatkar P.J., Tambe R., Sathaye S. Neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects of apigenin and luteolin in MPTP induced parkinsonism in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2014;86:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siddique Y.H., Jyoti S., Naz F., Afzal M. Protective effect of apigenin in transgenic Drosophila melanogaster model of Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacology. 2011;3:790–795. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long J., Gao H., Sun L., Liu J., Zhao-Wilson X. Grape extract protects mitochondria from oxidative damage and improves locomotor dysfunction and extends lifespan in a Drosophila Parkinson's disease model. Rejuvenation Res. 2009;12:321–331. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jollow D.J., Mitchell J.R., Zampaglione N.A., Gillette J.R. Bromobenzene-induced liver necrosis Protective role of glutathione and evidence for 3,4-bromobenzene oxide as the hepatotoxic metabolite. Pharmacology. 1974;11:151–169. doi: 10.1159/000136485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habig W.H., Pabst M.J., Fleischner G., Gatmaitan Z., Arias I.M., Jakoby W.B. The identity of glutathione S-transferase B with ligandin, a major binding protein of liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1974;71:3879–3882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohkawa H., Nobuko O., Yagi K. Reaction of linoleic acid hydroperoxide with thiobarbituric acid. J Lipid Res. 1978;19:1053–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins C.L., Morgan P.E., Davies M.J. Quantification of protein modification by oxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:965–988. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McEwen C.M. Human plasma monoamine oxidase I. Purification and identification. J Biol Chem. 1965;240(5):2003–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlumpf M., Lichtensteiger W., Langemann H., Waser P.G., Hefti F. A fluorometric micromethod for the simultaneous determination of serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine in milligram amounts of brain tissue. Biochem Pharmacol. 1974;23:2437–2446. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(74)90235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fu M.S., Zhu B.J., Luo D.W. Apigenin prevents TNF-alpha induced apoptosis of primary rat retinal ganglion cells. Cell Mol Biol. 2014;60:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta S., Afaq F., Mukhtar H. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B, Bax and Bcl-2 in induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by apigenin in human prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3727–3738. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanazawa K., Uehara M., Yanagitani H., Hashimoto T. Bioavailable flavonoids to suppress the formation of 8-OHdG in HepG2 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;455:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ha S.K., Lee P., Park J.A., Oh H.R., Lee S.Y., Park J.H. Apigenin inhibits the production of NO and PGE 2 in microglia and inhibits neuronal cell death in a middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced focal ischemia mice model. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:878–886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang T., Su J., Guo B., Wang K., Li X., Liang G. Apigenin protects blood–brain barrier and ameliorates early brain injury by inhibiting TLR4-mediated inflammatory pathway in subarachnoid hemorrhage rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;28:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auluck P.K., Chan H.Y., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M., Bonini N.M. Chaperone suppression of alpha-synuclein toxicity in a Drosophila model for Parkinson's disease. Science. 2002;295:865–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1067389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munoz-Soriano V., Paricio N. Drosophila models of Parkinson’s disease: discovering relevant pathways and novel therapeutic strategies. Parkinson’s Dis. 2011;2011:1–14. doi: 10.4061/2011/520640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joseph J.A., Shukitt-Hale B., Denisova N.A., Prior R.L., Cao G.H., Martin A. Long term dietary strawberry, spinach or vitamin E supplementation retards the onset of age-related neuronal signal-transduction and cognitive behavioural deficits. J Neurosci. 1988;18:8047–8055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-08047.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cantutui-Castelvetri I., Shukitt-Hale B., Joseph J.A. Neurobehavioral aspects of anti-oxidants in ageing. Int Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:367–381. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lashmanova E., Proshkina E., Zhikrivetskaya S., Shevchenko O., Marusich E., Leonov S. Fucoxanthin increases lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. Pharmacol Res. 2015;100:228–241. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cencioni C., Spallotta F., Martelli F., Valente S., Mai A., Zeiher A.M. Oxidative stress and epigenetic regulation in ageing and age-related diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17643–17663. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vina J., Sastre J., Pallardo F.V., Gambini J., Borras C. Role of mitochondrial oxidative stress to explain the different longevity between genders: protective effect of estrogens. Free Radic Res. 2006;40:1359–1365. doi: 10.1080/10715760600952851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giasson B.I., Ischiropoulos H., Lee V.M.Y., Trojanowski J.Q. The relationship between oxidative/nitrative stress and pathological inclusions in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:1264–1275. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00804-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vertuani S., Angusti A., Manfredini S. The antioxidants and pro-antioxidants network: an overview. Cur Pharm Des. 2004;10:1677–1694. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pragason V., Kalaiselvi P., Sumitra K., Srinivasan S., Kumar A.P., Varalakshmi P. Immunological detection of nitrosative stress mediated modified Tamm–Horsfall glycoprotein (THP) in calcium oxalate stone formers. Biomarkers. 2006;11:153–163. doi: 10.1080/13547500500421138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alam Z.I., Daniel S.E., Lees A.J., Marsden D.C. A generalized increase in protein carbonyls in the brain in Parkinson’s but not incidental Lewy body disease. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1326–1329. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cookson M.R. The biochemistry of Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:29–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeyabal P.V.S., Syed M.B., Venkataraman M., Sambandham J.K., Sakthisekaran D. Apigenin inhibits oxidative stress-induced macromolecular damage in N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA)-induced hepatocellular carcinogenesis in Wistar albino rats. Mol Carcinogen. 2005;44:11–20. doi: 10.1002/mc.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan T.H., Jahangir T., Prasad L., Sultana S. Inhibitory effect of apigenin on benzo(a)pyrene-mediated genotoxicity in Swiss albino mice. J Phar Pharmacol. 2006;58:1655–1660. doi: 10.1211/jpp.58.12.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorenzo P.S., Rubio M.C., Medina J.H., Adler-Graschinsky E. Involvement of monoamine oxidase and noradrenaline uptake in the positive chronotropic effects of apigenin in rat atria. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;312:203–207. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson W.M., Wilson-Delfosse A.L., Mieyal J.J. Dysregulation of glutathione homeostasis in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients. 2012;4:1399–1440. doi: 10.3390/nu4101399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Y., Carvey P.M., Ling Z. Altered glutathione homeostasis in animals prenatally exposed to lipopolysaccharide. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang Y.C., Huang Y.T., Tsai S.H., Lin-Shiau S.Y., Chen C.F., Lin J.K. Suppression of inducible cyclooxygenase and inducible nitric oxide synthase by apigenin and related flavonoids in mouse macrophages. Carcinogene. 1999;20:1945–1952. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.10.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang S.S., Lee J.Y., Choi Y.K., Kim G.S., Han B.H. Neuroprotective effects of flavones on hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y neuroblostoma cells. Bio-org Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:2261–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cholbi M.R., Paya M., Alcaraz M.J. Inhibitory effects of phenolic compounds on CCl4-induced microsomal lipid peroxidation. Experientia. 1991;47:195–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01945426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Psotová J., Chlopčíková S., Miketová P., Hrbáč J., Šimánek V. Chemoprotective effect of plant phenolics against anthracycline-induced toxicity on rat cardiomyocytes: Part III. Apigenin, baicalelin, kaempherol, luteolin and quercetin. Phytother Res. 2004;18:516–521. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dreiseitel A., Korte G., Schreier P., Oehme A., Locher S., Domani M.S. anthocyanins and their aglycons inhibit monoamine oxidases A and B. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Naoi M., Maruyama W. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors as neuroprotective agents in age-dependent neurodegenerative disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2799–2817. doi: 10.2174/138161210793176527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mazzio E.A., Harris N., Soliman K.F. Food constituents attenuate monoamine oxidase activity and peroxide levels in C6 astrocyte cells. Planta Med. 1998;64:603–606. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin M., Lu S.S., Wang A.X., Qi X.Y., Zhao D., Wang Z.H. Apigenin attenuates dopamine-induced apoptosis in melanocytes via oxidative stress-related p38, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and Akt signalling. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu W., Kong S., Xie Q., Su J., Li W., Guo H. Protective effects of apigenin against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Inter J Mol Med. 2015;35:739–746. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang C.N., Chi C.W., Lin Y.L., Chen C.F., Shiao Y.J. The neuroprotective effects of phytoestrogens on amyloid β protein-induced toxicity are mediated by abrogating the activation of caspase cascade in rat cortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5287–5295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen H.Q., Wang X.J., Jin Z.Y., Xu X.M., Zhao J.W., Xie Z.J. Protective effect of isoflavones from Trifolium pratense on dopaminergic neurons. Neurosci Res. 2008;62:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joyeux M., Lobstein A., Anton R., Mortier F. Comparative antilipoperoxidant, antinecrotic and scavenging properties of terpenes and biflavones from Ginkgo and some flavonoids. Planta Med. 1995;61:126–129. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-958030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mazzio E.A., Close F., Soliman K.F. The biochemical and cellular basis for nutraceutical strategies to attenuate neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:506–569. doi: 10.3390/ijms12010506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solanki I., Parihar P., Mansuri M.L., Parihar M.S. Flavonoid-based therapies in the early management of neurodegenerative diseases. Adv Nutr Ann Int Rev J. 2015;6:64–72. doi: 10.3945/an.114.007500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siddique Y.H., Naz F., Jyoti S., Ali F., Fatima A., Khanam S. Protective effect of geraniol on the transgenic Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2016;43:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fatima A., Khanam S., Rahul Jyoti S., Naz F., Ali F. Protective effect of tangeritin in transgenic Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Front Biosci Elite. 2016;9:44–53. doi: 10.2741/e784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siddique Y.H., Naz F., Jyoti S. Effect of curcumin on lifespan, activity pattern, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in the brains of transgenic Drosophila model of Parkinson’s disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/606928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seidl S.E., Santiago J.A., Bilyk H., Potashkin J.A. The emerging role of nutrition in Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:36. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Birt D.F., Hendrich S., Wang W. Dietary agents in cancer prevention: flavonoids and isoflavonoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;90:157–177. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hu M., Chen J., Lin H. Metabolism of flavonoids via enteric recycling: mechanistic studies of disposition of apigenin in the Caco-2 cell culture model. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2003;307:314–321. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? J Neurochem. 2006;97:1634–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pannala A., Rice-Evans C.A., Halliwell B., Singh S. Inhibition of peroxynitrite-mediated tyrosine nitration by catechin polyphenols. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;232:164–168. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patisaul H.B. Phytoestrogen action in the adult and developing brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]