Abstract

Background

Those classified as Tae-Eum (TE)-type people in Sasang constitutional medicine (SCM) are prone to obesity. Although extensive clinical observations have confirmed this tendency, the underlying physiological mechanisms are unknown. Here, we propose a novel hypothesis using integrative physiology to explain this phenomenon.

Methods

Hypoactive lung function in the TE type indicates that respiration is attenuated at the cellular level—specifically, mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Because a functional reduction in cellular energy metabolism is suggestive of intrinsic hypoactivity in the consumption (or production) of metabolic energy, we reasoned that this tendency can readily cause weight gain via an increase in anabolism. Thus, this relationship can be derived from the graph of cellular metabolic power plotted against body weight. We analyzed the clinical data of 548 individuals to test this hypothesis.

Results

The statistical analysis revealed that the cellular metabolic rate was lower in TE-type individuals and that their percentage of obesity (body mass index >25) was significantly higher compared to other constitutional groups.

Conclusion

Lower cellular metabolic power can be an explanation for the obesity trend in TE type people.

Keywords: cellular metabolic power hypothesis, obesity, Sasang constitutional medicine, scaling law of metabolic rate, Tae-Eum type

1. Introduction

Clinical studies have shown that obesity causes several medical complications. It is an important risk factor for endocrine diseases such as diabetes and vascular conditions such as atherosclerosis.1 Moreover, obese individuals are prone to cancer and have a reduced life span.2 However, despite numerous investigations in humans and animals, the physiological mechanisms underlying obesity remain controversial.

Several studies have used Oriental medicine to investigate obesity. In particular, people classified as Tae-Eum (TE) type using the classification of Sasang constitutional medicine (SCM) are prone to obesity. SCM, a traditional Korean medicine, classifies people into four constitutional types, namely, TE, So-Eum (SE), Tae-Yang (TY), and So-Yang (SY), and treats patients using personalized herbal drugs according to constitutional type.3, 4, 5

Several clinical studies have shown that the TE individuals are prone to obesity and TE type is a risk factor for abdominal obesity and obesity-related diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic disorders.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Furthermore, several genes associated with obesity and metabolic diseases have different effects according to body constitution.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Recent studies have evaluated the effects of herbal drugs on obesity in TE-type individuals.21, 22

Although previous studies have established that TE individuals are prone to obesity, the physiological mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not well understood. Thus, here we propose a physiological hypothesis to explain obesity proneness in TE-type individuals, which we tested using epidemiological data.

As discussed in our review paper,23 TE individuals display an unbalanced seesawing of the lung and liver pair and have weak lung system (respiratory) function. This respiratory function is related to metabolic power in tissue. Mathieu et al24 and Jánský25 showed that mitochondrial density in skeletal muscle was proportional to the maximal aerobic rate. Thus, weak lung function is associated with low maximal aerobic capacity and reduced mitochondrial density in tissue, which may eventually result in reduced energy production in the body. TE-type individuals are thought to have a weak lung system, which, in turn, reduces the production of metabolic energy. Here, we represented the production capability of metabolic energy in human body by using cellular metabolic rate (CMP). Then, we hypothesized that the CMP of the TE type is weaker than that of the other types as a result of particular metabolic characteristics.

Humans are homeothermic mammals; thus, core temperature is maintained at a constant level regardless of the environmental temperature.26 The short-term response to a cold environment involves activation of the autonomic nervous system in the hypothalamus to minimize heat loss and maximize heat production by increasing sympathetic activity, stimulating nonshivering thermogenesis, and increasing the thickness of the insulating shell or initiating piloerection. In the long term, adaptation to cold stress involves reducing heat dissipation by decreasing the body surface area relative to body volume, known as Bergmann’s rule.27 Moreover, increased body weight decreases the body surface area/volume ratio, thereby reducing heat dissipation via body surface relative to body heat production.

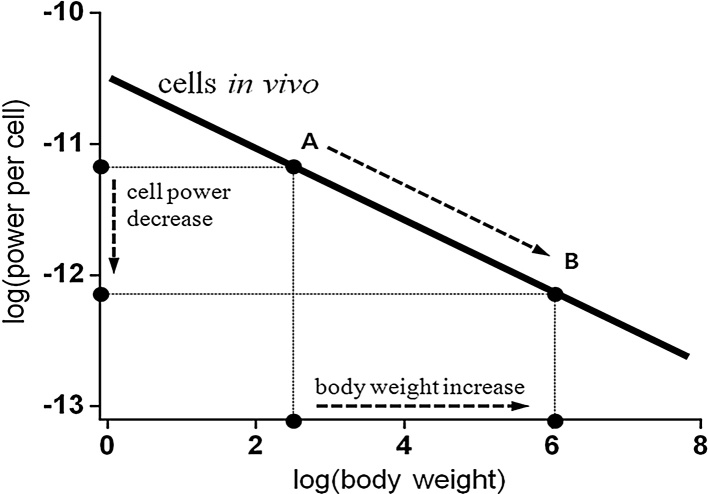

We used the CMP hypothesis to explain the scientific rationale linking weak lung function and obesity. Rising et al28, 29 showed that low core temperature may indicate an obesity-prone syndrome in humans, and Jéquier et al30 reported that obese individuals generally have increased thermal body insulation, suggesting that decreased energy production is compensated for by a reduction in energy dissipation into the environment. The decrease in heat generation activates a compensatory response by the body (an increase in heat generation and decrease in heat dissipation) and eventual weight gain.31 This effect is derived from the 3/4-power scaling law of metabolic rate; the basal metabolic rate (BMR) of an organism is proportional to body mass raised to the 3/4 power.32, 33 A corollary of the scaling relationship shows that CMP in vivo is negatively correlated with body mass, or that an organism with a larger body mass will have less CMP. According to this relationship, people with a low CMP readily gain body weight to compensate for a decrease in unit heat production and to prevent a decrease in core temperature (Fig. 1). A similar tendency can be hypothesized for TE-type individuals. Relatively low aerobic capacity may decrease mitochondrial density in the cell33, 34 resulting in a decrease in CMP and eventual increase in body mass.

Fig. 1.

The 3/4-power scaling law of metabolic rate shows that low cellular metabolic power can induce weight gain.

Based on the thermogenesis hypothesis, we proposed that the compensatory mechanism used to maintain temperature homeostasis readily increases body weight in TE individuals. To validate this, we analyzed clinical data to obtain the CMP value for each individual. Then we compared the CMP values of TE individuals to those of the other types.

2. Methods

Here, CMP value was the BMR value divided by body weight (CMP = BMR/Body weight). This method for determining CMP was developed by West et al.33

2.1. Analysis of epidemiological data

We analyzed epidemiological data to clarify the relationship between the tendency toward obesity in the TE type and CMP. Epidemiological data were collected from 548 apparently healthy volunteers (296 men and 252 women) between the ages of 20 and 40 years at the Asian Medical Center at Seoul, Republic of Korea, between 2009 and 2012. The study was approved by the Asian Medical Center Ethics Committee, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

We used the Sasang Constitution Analysis Tool (SCAT) developed by the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine to classify the Sasang constitutional type.35 The SCAT uses a multinomial logistic regression analysis based on the integrated data of facial features (two-dimensional images of the front and profile), body shape (width and circumference measurements), voice features, and questionnaire responses (personality traits and physiological symptoms) to classify constitutional types. The accuracy of the SCAT is higher than that of the Questionnaire for Sasang Constitution Classification II, the most commonly used diagnostic tool for Sasang typing.36 Because the prevalence of the TY type is extremely low in the Korean community, the current version of the SCAT only classified the TE, SE, and SY types.

2.2. Statistical analysis method

The data were analyzed using an analysis of variance. Table 1 shows the distribution of constitution types according to sex. CMP values for each physical constitution were obtained by measuring BMR. The InBody230 (BioSpace Inc., Cerritos, CA, USA) was used to measure oxygen consumption and calculate BMR during repeated tests conducted during 1 day. BMR was categorized according to weight to obtain the CMP value. Finally, body mass index (BMI), calculated as the body weight divided by the square of height, was used to quantify the degree of obesity in the data analysis. We used Scheffe’s test to evaluate the relative degree of statistical difference according to physical constitution (Table 2, Table 3) where “A” indicates the highest ranking among the three groups and “C” represents the lowest rank.

Table 1.

Physical constitution according to sex.

| TE type | SE type | SY type | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 101 (34.1%) | 87 (29.4%) | 108 (36.5%) | 296 (100%) |

| Females | 81 (32.1%) | 79 (31.3%) | 92 (36.5%) | 252 (100%) |

| Total | 182 (33.2%) | 166 (30.3%) | 200 (36.5%) | 548 (100%) |

SE, So-Eum type; SY, So-Yang type; TE, Tae-Eum type.

Table 2.

Comparison of target characteristics among physical constitution types for males.

| Mean ± SD | F | p | Scheffe’s test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMR (cal/d) | TE | 1782.73 ± 319.07 | 14.80 | <0.001 | A |

| SE | 1566.24 ± 279.47 | B | |||

| SY | 1770.14 ± 305.72 | A | |||

| CMP (cal/d/kg) | TE | 22.31 ± 3.75 | 10.07 | <0.001 | B |

| SE | 24.45 ± 3.89 | A | |||

| SY | 24.63 ± 4.48 | A | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | TE | 26.41 ± 2.71 | 121.78 | <0.001 | A |

| SE | 21.54 ± 1.74 | C | |||

| SY | 23.81 ± 1.80 | B | |||

| Height (cm) | TE | 174.25 ± 5.41 | 2.87 | 0.058 | |

| SE | 172.55 ± 5.69 | ||||

| SY | 174.18 ± 5.29 | ||||

| Weight (kg) | TE | 80.22 ± 9.23 | 105.85 | <0.001 | A |

| SE | 64.21 ± 6.54 | C | |||

| SY | 72.24 ± 6.42 | B | |||

| Age (y) | TE | 30.68 ± 6.81 | 1.11 | 0.330 | |

| SE | 29.86 ± 6.34 | ||||

| SY | 29.39 ± 5.81 |

BMI, body mass index; BMR, basal metabolic rate; CMP, cellular metabolic power; SD, standard deviation; SE, So-Eum type; SY, So-Yang type; TE, Tae-Eum type.

F value in Analysis of variance.

Table 3.

Comparison of target characteristics among physical constitution types for females.

| Mean ± SD | F | p | Scheffe’s test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMR (cal/d) | TE | 1346.14 ± 232.26 | 5.21 | 0.006 | A |

| SE | 1241.87 ± 235.54 | B | |||

| SY | 1256.28 ± 204.63 | B | |||

| CMP (cal/d/kg) | TE | 21.63 ± 3.76 | 7.73 | 0.001 | B |

| SE | 23.96 ± 4.42 | A | |||

| SY | 23.32 ± 3.49 | A | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | TE | 24.38 ± 2.98 | 93.71 | <0.001 | A |

| SE | 20.01 ± 1.68 | C | |||

| SY | 21.05 ± 1.46 | B | |||

| Height (cm) | TE | 160.38 ± 5.30 | 1.00 | 0.370 | |

| SE | 161.26 ± 5.06 | ||||

| SY | 160.13 ± 5.73 | ||||

| Weight (kg) | TE | 62.59 ± 7.02 | 81.80 | <0.001 | A |

| SE | 52.05 ± 5.12 | B | |||

| SY | 53.96 ± 4.48 | B | |||

| Age (y) | TE | 31.19 ± 6.75 | 0.46 | 0.633 | |

| SE | 31.25 ± 7.12 | ||||

| SY | 30.36 ± 6.80 |

BMI, body mass index; BMR, basal metabolic rate; CMP, cellular metabolic power; SD, standard deviation; SE, So-Eum type; SY, So-Yang type; TE, Tae-Eum type.

F value in Analysis of variance.

3. Results

The comparison of the target characteristics among physical constitution types is shown for males in Table 2 and females in Table 3. All variables with the exception of age and height were significantly different among groups. Weight and BMI were significantly correlated in males. TE-type individuals had the highest body weight and BMI. However, Scheffe’s test revealed that BMR was not significantly different between the TE and SY types. For females, BMI and body weight were most highly correlated with the TE type, and BMR was highest in the TE group (Scheffe’s test value was “A” only for the TE type).

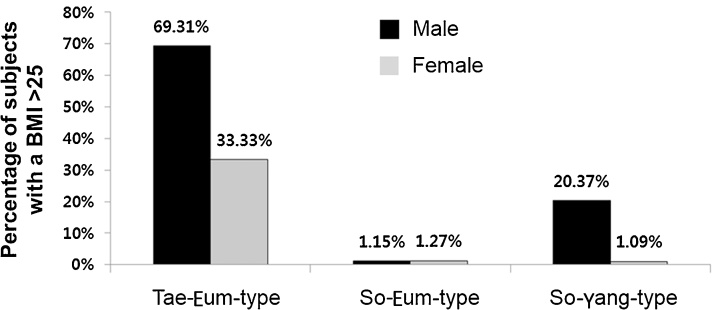

As shown in Table 2, Table 3, the average value of CMP for the SE type was relatively higher than that of the other constitutions in both males and females. Conversely, CMP was markedly lower in the TE type in both males and females. The percentage of individuals classified as obese (BMI >25, International Health Organization criteria) was lowest in SE-type individuals and higher in the TE type compared with the other constitutions. Of the 182 people in the TE type group, 69% of males and 33% of females were classified as obese (BMI >25; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of individuals with a BMI >25 according to physical constitution and sex. BMI, body mass index; SE, So-Eum type; SY, So-Yang type; TE, Tae-Eum type.

4. Discussion

TE-type individuals have relatively high BMIs and are more prone to obesity than those in the other constitution groups. However, the physiological mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not known. We have proposed a novel CMP hypothesis to explain the tendency toward obesity in the TE type.

The hypothesis can be explained as follows. If the TE type has a relatively weak lung system, their maximum aerobic capability would be reduced. Because maximum aerobic rate is directly related to mitochondrial density in the cell, cellular heat production and, thus, the heat production capability of TE-type individuals would be reduced. Thus, the TE type experiences chronic cold stress, and because human core temperature is maintained at nearly a constant level, cold temperatures stimulate acute compensatory mechanisms and chronic cold stress activates the long-term adaptation mechanism leading to weight gain.

In a previous study,37 we showed that energy consumption was low, whereas energy storage was overactive in the TE type. Because the quantity of consumed energy in the human body is the same as that produced, the energy consumption function is consistent with energy production. Thus, energy production in the TE type is suboptimal.

Intracellular mitochondria produce most of the energy in the body, which drives CMP. Here, we posit that energy production is lower in TE-type individuals than in those with other constitution types. Our CMP hypothesis can be summarized as the follows. Low energy production in the TE type leads to a reduction in the generation of body heat. However, because human core temperature is maintained at a constant level, the reduction in body heat activates homeostatic mechanisms to prevent variation in the core temperature, and weight gain is the result of a long-term process to maintain temperature homeostasis (Fig. 1). Thus, weight gain is the result of a weak CMP in TE-type individuals.

We analyzed data from 548 individuals to assess the feasibility of our hypothesis (Table 2, Table 3, Fig. 2). Our results showed that CMP values in TE-type males and females were lower than those found in the other constitution types. However, BMR was not significantly higher in TE-type males than in those with other constitution types (Table 2). This finding suggests that CMP is a better indicator of TE-type metabolic characteristics than BMR, which supports CMP as a physiological mechanism underlying the tendency toward obesity in TE-type individuals.

Although our data clearly explain the proneness of the TE type to obesity from a physiological viewpoint, our study has several limitations. First, the demographic data of TY-type individuals were excluded from the study. Such information should be included to improve the analysis. Furthermore, our sample size of 548 individuals was relatively small, and a large-scale study is necessary to validate our hypothesis. However, these limitations do not detract from our results supporting the CMP hypothesis.

In conclusion, we propose a physiological hypothesis to explain the tendency toward obesity in TE-type individuals. The hypothesis is based on the 3/4-power scaling law of metabolic rate, the principle of temperature homeostasis, and weight gain as a long-term adaptation to prevent cold stress. Thus, we hypothesized that the reduced cellular metabolic capability of TE-type individuals may lead to weight gain as a mechanism of long-term homeostatic adaptation. We used CMP values to quantify cellular energy metabolism and validated our hypothesis by analyzing data collected in the clinic. Our results revealed that the CMP values of the TE type group were significantly lower than those of individuals in the other constitution groups, providing further evidence of a physiological impact of CMP on obesity in SCM.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (No. NRF-2015M3A9B6027139).

References

- 1.Avenell A., Broom J., Brown T.J., Poobalan A., Aucott L., Stearns S.C. Systematic review of the long-term effects and economic consequences of treatments for obesity and implications for health improvement. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1–182. doi: 10.3310/hta8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker S., Dossus L., Kaaks R. Obesity related hyperinsulinaemia and hyperglycaemia and cancer development. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2009;115:86–96. doi: 10.1080/13813450902878054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J.Y., Pham D.D. Sasang constitutional medicine as a holistic tailored medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009;6:11–19. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chae H., Lyoo I.K., Lee S.J., Cho S., Bae H., Hong M. An alternative way to individualized medicine: psychological and physical traits of Sasang typology. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:519–528. doi: 10.1089/107555303322284811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jang E.S., Baek Y.H., Park K.H., Lee S.W. Can anthropometric risk factors important in Sasang constitution be used to detect metabolic syndrome? Eur J Integr Med. 2014;6:82–89. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang E.S., Baek Y.H., Park K.H., Lee S.W. Could the Sasang constitution itself be a risk factor of abdominal obesity? BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:72. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee T.G., Koh B.H., Lee S. Sasang constitution as a risk factor for diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009;6:99–103. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi K., Lee J., Yoo J., Lee E., Koh B., Lee J. Sasang constitutional types can act as a risk factor for insulin resistance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91:e57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J., Lee J., Lee E., Yoo J., Kim Y., Koh B. The Sasang constitutional types can act as a risk factor for hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2011;33:525–532. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2011.561901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song K.H., Yu S.G., Kim J.Y. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome according to Sasang constitutional medicine in Korean subjects. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2017:646794. doi: 10.1155/2012/646794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang E., Baek Y., Park K., Lee S. The Sasang constitution as an independent risk factor for metabolic syndrome: propensity matching analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:492941. doi: 10.1155/2013/492941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho N.H., Kim J.Y., Kim S.S., Shin C. The relationship of metabolic syndrome and constitutional medicine for the prediction of cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2013;7:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S.K., Yoon D.W., Yi H., Lee S.W., Kim J.Y., Shin C. Tae-eum type as an independent risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:910382. doi: 10.1155/2013/910382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J.H., Kwon Y.D., Hong S.H., Jeong H.J., Kim H.M., Um J.Y. Interleukin-1 beta gene polymorphism and traditional constitution in obese women. Int J Neurosci. 2008;118:793–805. doi: 10.1080/00207450701242883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song J.S., Jeong H.J., Kim S.J., Son M.S., Na H.J., Song Y.S. Interleukin-1 alpha polymorphism −889C/T related to obesity in Korean Tae-eum women. Am J Chin Med. 2008;36:71–80. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X0800559X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Um J.Y., Lee J.H., Joo J.C., Kim K.Y., Lee E.H., Shin T. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphism and Sasang constitution in cerebral infarction. Am J Chin Med. 2005;33:547–557. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X05003156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Um J.Y., Joo J.C., Kim K.Y., An N.H., Lee K.M., Kim H.M. Angiotensin converting enzyme gene polymorphism and traditional Sasang classification in Koreans with cerebral infarction. Hereditas. 2003;138:166–171. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5223.2003.01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Um J.Y., Kim H.M., Mun S.W., Song Y.S., Hong S.H. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene polymorphism and traditional classification in obese women. Int J Neurosci. 2006;116:39–53. doi: 10.1080/00207450690962334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cha S.W., Koo I., Park B.L., Jeong S., Choi S.M., Kim K.S. Genetic effects of FTO and MC4R polymorphisms on body mass in constitutional types. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:106390. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cha S., Yu H., Kim J.Y. Bone mineral density-associated polymorphisms are associated with obesity-related traits in Korean adults in a sex-dependent manner. PLoS One. 2012;7:e53013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park S., Park J.S., Cheon C., Yang Y.J., An C., Jang B.H. A pilot study to evaluate the effect of Taeumjowi-tang on obesity in Korean adults: study protocol for a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Trials. 2012;13:33. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S., Nahmkoong W., Cheon C., Park J.S., Jang B.H., Shin Y. Efficacy and safety of Taeeumjowi-tang in obese Korean adults: a double-blind, randomized, and placebo-controlled pilot trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:498935. doi: 10.1155/2013/498935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shim E.B., Lee S., Kim J.Y., Earm Y.E. Physiome and Sasang constitutional medicine. J Physiol Sci. 2008;58:433–440. doi: 10.2170/physiolsci.RV004208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathieu O., Krauer R., Hoppeler H., Gehr P., Lindstedt S.L., Alexander R.M. Design of the mammalian respiratory system: VII: Scaling mitochondrial volume in skeletal muscle to body mass. Respir Physiol. 1981;44:113–128. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(81)90079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jánský L. Total cytochrome oxidase activity and its relation to basal and maximal metabolism. Nature. 1961;189:921–922. doi: 10.1038/189921a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell N.A. Benjamin Cummings; Menlo Park, CA: 1987. Biology. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schreider E. Geographical distribution of the body-weight/body-surface ratio. Nature. 1950;165:286. doi: 10.1038/165286b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rising R., Keys A., Ravussin E., Bogardus C. Concomitant interindividual variation in body temperature and metabolic rate. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:E730–E734. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.4.E730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rising R., Fontvieille A.M., Larson D.E., Spraul M., Bogardus C., Ravussin E. Racial difference in body core temperature between Pima Indian and Caucasian men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jéquier E., Gygax P.H., Pittet P., Vannotti A. Increased thermal body insulation: relationship to the development of obesity. J Appl Physiol. 1974;36:674–678. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.36.6.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dulloo A.G., Seydoux J., Jacquet J. Adaptive thermogenesis and uncoupling proteins: a reappraisal of their roles in fat metabolism and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:587–602. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.West G.B., Brown J.H., Enquist B.J. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science. 1997;276:122–126. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.West G.B., Woodruff W.H., Brown J.H. Allometric scaling of metabolic rate from molecules and mitochondria to cells and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2473–2478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012579799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frankenfield D.C., Rowe W.A., Smith J.S., Cooney R.N. Validation of several established equations for resting metabolic rate in obese and nonobese people. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1152–1159. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)00982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Do J.H., Jang E., Ku B., Jang J.S., Kim H., Kim J.Y. Development of an integrated Sasang constitution diagnosis method using face, body shape, voice, and questionnaire information. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park H., Chun J.J., Kim J., Kim K. A study on clinical application of the QSCCII (Questionnaire for the Sasang Constitution Classification II) J Sasang Const Med. 2002;2002(14):35–44. [In Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shim E.B., Lee S.W., Kim J.Y., Leem C.H., Earm Y.E. Taeeum people in Sasang constitutional medicine have a reduced mitochondrial metabolism. Integr Med Res. 2012;1:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]