Abstract

Background

Diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas (DIPG) and high-grade astrocytomas (HGA) continue to have dismal prognoses. The combination of cetuximab and irinotecan was demonstrated to be safe and tolerable in a previous pediatric phase 1 combination study. We developed this phase 2 trial to investigate the safety and efficacy of cetuximab given with radiation therapy followed by adjuvant cetuximab and irinotecan.

Methods

Eligible patients age 3–21 years had newly diagnosed DIPG or HGA. Patients received radiation therapy (5940 cGy) with concurrent cetuximab. Following radiation, patients received cetuximab weekly and irinotecan daily × 5 for two weeks every 21 days for 30 weeks. Correlative studies were performed. The regimen was to be considered promising if the patients with one-year PFS for DIPG and HGA was at least 6 of 25 and 14 of 26 patients respectively.

Results

Forty-five evaluable patients were enrolled (25 DIPG, 20 HGA). Six patients with DIPG patients and five with HGA patients were progression-free at 1 year from the start of therapy with one-year progression-free survivals of 29.6% and 18%, respectively. Fatigue, gastrointestinal complaints, electrolyte abnormalities, and rash were the most common adverse events and generally grade 1 and 2. Increased EGFR copy number but no K-ras mutations were identified in available samples.

Conclusions

The trial did not meet the predetermined endpoint to deem this regimen successful for HGA. While the trial met the predetermined endpoint for DIPG, OS was not markedly improved from historical controls therefore does not merit further study in this population.

Keywords: Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, pediatric high-grade astrocytoma, radiation, chemotherapy, cetuximab

Introduction

While treatment advances have steadily improved the prognosis of most pediatric cancers, the survival rates for DIPG and HGA remain dismal. Together, they account for about 20% of pediatric brain tumors, yet are responsible for over 40% of the mortality in children with brain tumors.1

Pediatric HGA, while molecularly different from adult HGA2,3, have similarly poor outcomes with 3-year progression-free survival of 13–22% for anaplastic astrocytomas and 7–15% for glioblastoma multiforme.4–6 Standard of care for this population remains maximally safe surgical resection, involved-field radiation therapy and chemotherapy; however, no optimal chemotherapy regimen has been established.4–6

DIPG have even worse survival with a median survival rate under one year.7 Despite many attempts to improve outcomes, radiation therapy remains the only treatment with therapeutic benefit8. The 1-year progression-free survival rates for DIPG continues to be approximately 10–15%.9,10

Cetuximab (Erbitux®; Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN) is a high-affinity chimeric monoclonal antibody to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) that inhibits ligand receptor activation through competitive ligand binding and induces internalization of the bound receptor.11,12 Cetuximab has demonstrated activity as a single agent and in combination with chemotherapy or radiation therapy in non-small cell lung cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and KRAS wild-type colorectal cancer.13–17

The EGFR pathway is frequently altered in adult HGA with overexpression, mutation, or amplification in approximately half of GBMs.18–20 While pediatric HGA less commonly harbor EGFR amplification, increased expression is seen suggesting that the EGFR pathway is a potential therapeutic target in HGA.2,21,22

Despite limited single agent activity in HGA,23–25 irinotecan has modest activity against HGA in combination with other chemotherapies.26–28 The addition of cetuximab to irinotecan enhances the anti-tumor activity of irinotecan in preclinical29 and clinical investigations of colorectal cancer.13,14 Single agent cetuximab induces objective tumor responses in adult HGA.30

The Pediatric Oncology Experimental Therapeutics Investigators’ Consortium (POETIC) performed the pediatric phase I study of cetuximab in combination with irinotecan,31 which included primary central nervous system (CNS) tumors. The study established cetuximab 250mg/m2 weekly plus irinotecan 16mg/m2/day as the pediatric recommended phase II dosing with manageable toxicities including hematologic, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and rash.31 Twelve of 26 (46.2% ) patients with CNS tumors had clinical benefit, with two patients having confirmed sustained partial responses. Due to the activity seen in the patients with CNS tumors, specifically HGA, we performed this phase II study in children with newly diagnosed HGA and DIPG evaluating the efficacy of cetuximab with radiation followed by weekly cetuximab with irinotecan.

Materials and Methods

Subject Eligibility

Patients 3 to 21 years of age with newly diagnosed HGA or DIPG were eligible. The diagnosis of HGA was confirmed histologically by an institutional pathologist. Patients with DIPG were eligible based on classic clinical findings and radiologic diagnosis (MRI). Therapy was required to start within 42 days of resection or biopsy or from radiologic diagnosis in patients with HGA or DIPG respectively. Other eligibility criteria included performance score ≥50 and adequate hematopoetic, hepatic and renal function. Patients were excluded if they had leptomeningeal or extra-neural metastases; prior chemotherapy or radiation; prior therapy with an EGFR pathway-targeted medicine; history of severe infusion reaction to a monoclonal antibody; uncontrolled cardiac disease; or known Gilbert’s syndrome.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards/institutional ethics committees at each institution. All patients or parents/legal guardians provided written informed consent; assent was obtained from patients when appropriate, in accordance with local guidelines.

Study Design

The primary objectives were to determine the proportion of patients with HGA and DIPG achieving one-year progression-free survival (PFS) receiving cetuximab and external beam radiation therapy followed by cetuximab and irinotecan and to determine the safety of weekly cetuximab in conjunction with involved field external beam radiation therapy. Secondary objectives were to estimate the time to progression (TTP) and overall survival (OS) in each cohort; to explore associations between primary tumor tissue molecular markers and tumor response; and to investigate serum inflammatory cytokines present with development of cetuximab-related rash.

Once enrolled, patients received two phases of therapy. During the first phase, patients received involved field external beam radiation therapy to a dose of 5940 cGy in 33 fractions (180 cGy). During radiation, cetuximab was administered at 250 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) weekly for six doses. Premedication with diphenhydramine was recommended. The second phase of therapy began 28–56 days after the completion of radiation and once the patient had adequate count recovery and organ function. Patients who were unable to start phase 2 within 56 days of completing radiation were removed from the study. The second phase of therapy consisted of irinotecan 16mg/m2/day over one hour for five days, given two consecutive weeks and cetuximab once weekly at 250mg/m2/dose IV in 21-day cycles. On days when both drugs were infused, irinotecan was administered after the cetuximab.

Subsequent cycles were started after evidence of hematologic recovery and adequate resolution of other toxicities. Patients received 10 cycles of therapy provided they did not meet criteria for study removal. Patients with stable or better disease after 10 cycles could continue on therapy at the discretion of the treating physician until a criterion for study removal was met.

Patient Evaluation

Within 30 days prior to starting therapy, a history and physical, laboratory studies, and imaging were obtained. During the first phase, physical exams and laboratories were performed weekly. During the second phase, physical exams and laboratories were performed prior to the start of each cycle. Disease evaluations with MRI were obtained prior to the second phase of therapy, then every third cycle thereafter. Following completion of therapy, MRIs were obtained every three months for a year then every three months until 42 months post-completion of therapy or disease progression. Response was evaluated in 2-dimensions using modified MacDonald Criteria by the institutions.32 Patients were followed for relapse and survival outcomes after protocol-prescribed therapy was completed.

Dose Modifications

Toxicities were assessed throughout the study via the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Event (CTCAE version 3.0). All toxicities were collected during treatment and for 30 days after the last dose of cetuximab. Grade 1 or 2 cetuximab infusion reactions required a 50% reduction in infusion rate; grade 3 or 4 infusion reactions required permanent discontinuation of cetuximab. Cetuximab-related rash was managed symptomatically. Cetuximab was held for for ≥grade 3 acneiform rash. Cetuximab was reduced by 50mg/m2 with recurrence and discontinued for greater than two weeks’ treatment delay or 3 dose reductions were required. Diarrhea prophylaxis with an oral cephalosporin was permitted and loperamide usage for diarrhea was encouraged. Irinotecan was dose-reduced by 2mg/m2/day for Grade 3–4 diarrhea or for >7 day delay due to hematopoietic toxicity, and held for elevated total bilirubin until <2.0 mg/dL.

Statistical Design and Analysis

A single stage design with 80% power and 5% type I error was utilized for each cohort. For the DIPG cohort, the progression-free proportion at one year was deemed unacceptable if < 10% and promising if ≥30%. If ≥6 of the planned 25 patients were alive and progression-free at one year, the treatment would be declared worthy of further testing. HGA cohort required a progression-free proportion of >60% to be deemed promising and would be unacceptable if <35%4. If ≥14 of the planned 26 patients were alive and progression-free at one year, the treatment would be worthy of further testing.

PFS at one year was assessed for DIPG and HGA separately and defined as the proportion of patients who remained alive and progression-free one year after the initiation of therapy; remaining patients were censored at the date of last follow-up. All patients who received at least one day of therapy were evaluable for response. Those who were alive and progression-free at one year by clinical and imaging assessment were considered progression-free for the primary endpoint. Patients who withdrew consent for further study treatment but had progression within 6 months of withdrawal were considered as progressing on their date of progression. Those patients who withdrew and had unknown progression date or progression more than 6 months after withdrawal were censored at the date of last treatment. One patient withdrew consent and was lost to follow-up.

TTP was defined similarly to PFS except the 3 patients who died without documented progression were censored at the date of death. OS was defined as time from therapy start to death or last follow-up. Event free survival (EFS) was defined similarly to PFS except patients who withdrew consent or stopped study protocol due to toxicity were assessed as events on the day of last treatment. OS, PFS and TTP were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier and Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.1.2 (www.r-project.org) and GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Tumor Tissue Analysis

Paraffin embedded tumor sections were obtained from 19 of 23 patients who underwent surgery (18 HGA, 1 DIPG). Snap-frozen tumor from primary biopsy or resection was obtained from nine patients. One patient with DIPG had snap-frozen tissue available without paraffin tumor specimen. Genetic markers, EGFR copy number amplification and KRAS mutation were screened in the samples as exploratory aims.33,34

Evaluation of EGFR copy number by FISH

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue slides were evaluated for EGFR copy number by a dual-color FISH assay using the Vysis LSI EGFR SpectrumOrange/CEP7 SpectrumGreen probe set (Abbott Molecular Cat# 05J48-001).35

KRAS sequencing

DNA was extracted from snap-frozen or FFPE material. DNA was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified with forward (5′AAGGCCTGCTGAAAATGAC) and reverse (5′TGGTCCTGCACCAGTAATATG) KRAS exon 2 primers. The purified PCR products were sequenced using an ABI 3730 automated sequencer.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry analyses were used to measure protein expression of EphA2 and pAKT, previously identified positive and negative predictive markers for cetuximab responsiveness.36,37 Sections were de-paraffinized, antigens unmasked and stained for EphA2 (Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA; rabbit clone SP169; cat#: M4690; 1:200) and pAKT (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA; rabbit polyclonal; cat#: 3787; Lot: #8; 1:50). Scoring of pAKT and EphA2 IHC was performed as previously published.37,38

Gene expression analysis

Snap frozen tumor samples were analyzed using the Human Genome U133plus2 Array (Affymetrix) platform as described previously.39 mRNAs corresponding to predictive markers implicated in cetuximab responsiveness were selected (see Supplemental Table S1 for list of mRNAs, corresponding probe sets and PMID for publications reporting cetuximab treatment association). Samples were dichotomized into high (>mean) and low (<mean) expression for Kaplan-Meier analyses.

Rash-associated Cytokine Analysis

As the development of rash during EGFR-directed therapies can correlate with clinical response,40 serum was collected from all patients prior to the initial dose of cetuximab. Additional serum was collected with the development of rash and with any progression of rash. Control samples were collected from patients without rash prior to each of the first four cycles of cetuximab/irinotecan. Samples were assayed for a panel of 67 inflammation/immunity related cytokines and peptides using a multiplex bead-based immunoassay system as described previously.41,42 The quantity of cytokines found in serum samples were analyzed using paired t-test (p<0.05 and Log2 Fold change >0.5 or <−0.5) to compare pre- and post-treatment protein levels.43 Pre-treatment cytokine expression was compared to post cycle 1 expression in eight patients who did not develop rash.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Forty-eight patients were enrolled between December 2009 and March 2012; 27 in the DIPG stratum and 21 in the HGA stratum. One patient with HGA and two with DIPG withdrew prior to receiving therapy and were excluded from any further analysis. Forty-five patients (25 DIPG and 20 HGA) were treated on study therapy (Table 1); all were assessable for toxicity. One patient was taken off study after receiving a partial dose of cetuximab and was inevaluable for efficacy analysis. All of the patients with HGA and two with DIPG underwent surgical resection or biopsy (Table 1). Patients received a median of seven cycles of therapy (1–39). Eight patients in total withdrew from study. Seven (2 HGA, 5 DIPG) withdrew from study treatment prior to progression due to parent/patient preference. One patient from each stratum withdrew after phase 1 of therapy and five patients withdrew after 1–5 cycles in phase 2. One patient with DIPG withdrew for excessive toxicity after 2 cycles of cetuximab and irinotecan.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Number of Patients (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 21 (47%) | ||

| Female | 24 (53%) | |||

| Median age in years (range) | 8 (3–19) | |||

| Tumor | HGA | 21 (47%) | ||

| Grade 3 | 12 (43%) | |||

| Grade 4 | 9 (57%) | |||

| DIPG | 25 (56%) | |||

| Surgery | None | 23 (49%) | ||

| Biopsy | 10 (22 %) HGA - 8 (35%) DIPG - 2 (8%) |

|||

| Subtotal resection | HGA – 9 (45%) | |||

| Gross Total resection | HGA - 4 (20%) | |||

| Performance status | ≥ 50 – 60 | 8 (17%) | ||

| 70 – 80 | 10 (21.2%) | |||

| 90 – 100 | 27 (59.6%) | |||

Efficacy and survival

Forty-four patients were eligible for evaluation of the primary outcome, the number of patients progression-free at one year. Five patients with HGA (25%) and six with DIPG (24%) had not progressed at one year meeting the predetermined criteria for a promising regimen for the DIPG stratum only. As 14 of the patients with HGA had progressed prior to one year, it was determined that the study would not meet the predetermined endpoint and the stratum was closed before completing planned enrollment. At last follow-up, five patients with HGA and one with DIPG remained alive at 25–45 months (HGA) and 42 months (DIPG) from start of treatment.

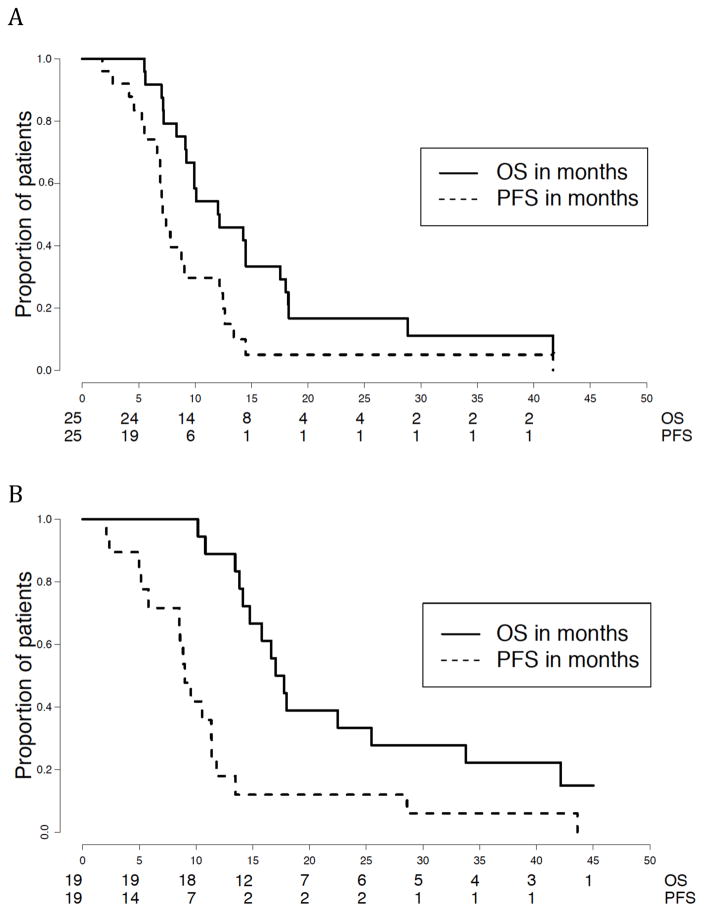

For the 25 patients with DIPG, the median PFS and TTP were the same at 7.12 months (95% CI: 6.89, 12.5) with a 1-year PFS based on Kaplan-Meier estimate of 29.6% (95% CI: 15–58%). The median PFS and TTP for the 19 patients with HGA were also the same at 9.02 months (95% CI: 8.52, 11.8) with a 1-year PFS of 18% (95% CI: 6–50%) (Figure 1A). The median event-free survival for HGA was 8.9 months (95% CI: 5.8, 11.8) and 6.9 months (95% CI: 5.34, 9.05) for DIPG. The median OS for the HGA stratum was 17.4 months (95% CI: 14.72, 42.1) and 12.1 months (95% CI: 9.93, 18) for DIPG (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

One year progression-free and overall survival

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for DIPG (A) and HGA (B)

Dashed Line - Progression-free survival Solid Line - Overall survival

Thirteen patients (6 DIPG, 7 HGA) completed the full 10 cycles of cetuximab and irinotecan. Four patients (3 DIPG, 1 HGA) received therapy beyond 10 cycles at the discretion of the physician and family. One patient with DIPG remained on therapy for 39 cycles (over 3 years) until progression of disease.

Toxicity

Cetuximab combined with radiation therapy was well-tolerated. The majority of toxicities were grade 1 and 2, with diarrhea, hypokalemia and lymphopenia being the most common therapy-related adverse events (possibly, probably or definitely attributed to study therapy) and the most frequent grade 3–4 events (Table 2). Gastrointestinal complaints, specifically diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, occurred frequently in 68–75% of patients; but grade 3 toxicity was ≤15% and there were no grade 4 events. Anemia occurred in almost half of all patients, but was mainly grade 1–2. Thrombocytopenia was only grade 1 and occurred in 11% of patients.

TABLE 2.

Therapy-related Adverse Events occurring 15 % or more patients

| CTCAE v3.0 term | All Grades (%) | Grade 3–4 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypokalemia | 34 (75.6) | 18 (40) |

| Diarrhea | 34 (75.6) | 7 (15.6) |

| Lymphopenia | 33 (73.3) | 26 (57.7) |

| Nausea | 33 (73.3) | 4 (8.9) |

| Leukopenia (total WBC) | 31 (68.9) | 7 (15.6) |

| Vomiting | 31 (68.9) | 6 (13.3) |

| Dry Skin | 30 (66.7) | 0 |

| Elevated ALT, SGPT | 28 (62.2) | 5 (11.1) |

| Fatigue | 27 (60) | 1 (2.2) |

| Rash – acne/acneiform | 27 (60) | 1 (2.2) |

| Hyperglycemia | 25 (55.6) | 4 (8.9) |

| Anorexia | 24 (53.3) | 9 (20) |

| Rash – desquamation | 24 (53.3) | 3 (6.7) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 23 (51.1) | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 23 (51.1) | 2 (4.4) |

| Alopecia | 23 (51.1) | 0 |

| Fever, in absence of neutropenia | 20 (44.4) | 0 |

| Anemia | 19 (42,2) | 2 (4.4) |

| Pain, Headache | 19 (42.2) | 2 (4.4) |

| Bicarbonate, Low | 18 (40) | 0 |

| Dermatology, skin, other | 18 (40) | 1 (2.2) |

| Hyponatremia | 18 (40) | 5 (11.1) |

| Elevated AST, SGOT | 17 (37.8) | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 17 (37.8) | 6 (13.3) |

| Pain, Abdomen | 17 (37.8) | 1 (2.2) |

| Constipation | 16 (35.6) | 1 (2.2) |

| Infection, other | 14 (31.1) | 4 (8.9) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 13 (28.9) | 2 (4.4) |

| Weight Loss | 13 (28.9) | 2 (4.4) |

| Cough | 11 (24.4 | 0 |

| Dehydration | 11 (24.4) | 2 (4.4) |

| Dizziness | 10 (22.2) | 0 |

| Pain, Other | 10 (22.2) | 0 |

| Sinus Tachycardia | 10 (22.2) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 9 (20) | 1 (2.2) |

| Pruritis/itching | 9 (20) | 0 |

| Hypermagnesemia | 8 (17.8) | 0 |

| Pain, throat/larynx | 7 (15.6) | 0 |

| Allergic Reaction/Hypersensitivity | 4 (8.9) | 2 (4.4) |

Electrolyte abnormalities were common but generally mild. Development of rash, either acneiform and/or desquamation was seen in the majority of patients (60% and 53.3%, respectively) however grade 3 events were rare. Allergic reaction/hypersensitivity occurred in 4 patients (8.9%); half required permanent discontinuation of cetuximab. There were 48 occurrences of missed or delayed treatment due to toxicity. No patient required dose reductions of cetuximab. Irinotecan was dose reduced in five patients: two for excessive diarrhea, two due to prolonged neutropenia and one for elevated ALT/AST. No patient required more than one dose reduction for diarrhea. One patient stopped therapy for excessive toxicity (diarrhea) attributed to irinotecan.

Tumor Tissue Analysis

Eighteen HGA and one DIPG tumors were analyzed. EGFR copy number gain was seen in 18 of 19 specimens, however only 26% (5/19) demonstrated high-level gain (>4 copies). Most were balanced with CEP7 gain indicating EGFR over-expression without gene amplification. EGFR gene amplification as clusters of signals or double minutes was not detected. Log-rank analyses identified no significant association between high EGFR copy number gain and PFS or OS (p=0.46 and 0.71, respectively). No KRAS exon 2 mutations were found.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic phospho-AKT (pAKT) expression was observed in all samples, ranging from discrete areas of positivity (~10%) to strong staining throughout the sample. There was no significant association with PFS or OS by log-rank analyses (p=0.63 and 0.64). EphA2 appeared to stain a relatively infrequent infiltrating cell population and not tumor cells. No significant association of EphA2 score with PFS or OS was observed (p=0.60 and 0.72).

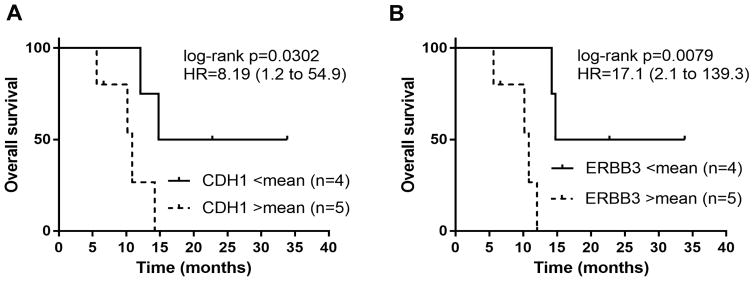

A panel of 45 gene transcripts for putative cetuximab predictive markers (Supplementary Table 1) extracted from gene expression microarray profiles of 9 tumor samples, were screened by Log-rank test for significant association with OS. Of these, low (defined as <mean) E-cadherin (CDH1; Affy probeset ID 201131_s_at) and v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3 (ERBB3; 226213_at) mRNA were associated with a significantly longer overall survival (HR=8.19 (CI 1.2 to 54.9); log-rank p=0.03 and HR=17.1 (CI 2.1 to 139.3; log-rank p=0.0079) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Decreased mRNA Expression of e-cadherin or ERBB3 results in improved overall survival in HGA.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival with comparison of low (<mean) versus high ( >mean) for CDH1 mRNA Expression (A) and ERBB3 mRNA expression (B)

Inflammatory Cytokines in Cetuximab-mediated Rash

In patients who did not develop rash, MDC, IL-13, I309, TARC and SDF-1a, were increased following treatment compared to baseline (Table 3). Six inflammatory cytokines had increased expression in patients with rash compared to baseline (TGFa, GRO, MDC, PDGF-a, PDGF-b and IL-33). However, none of these expression alterations were significant when adjusted for ‘false discovery rate’ (FDR) (Table 4). Additional studies with an expanded sample size are needed to further investigate these findings. Development of rash did not affect OS (p=0.38) or PFS (p=0.52).

TABLE 3.

Cetuximab Treatment Alters Cytokine Expression (n=6)

| Cytokine | Baseline Mean [pg/mL] | Post 6 doses – no rash Mean [pg/mL] | p-value (paired t-test) | Adj. p-value (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDC | 745 | 1381 | 0.03 | 0.41 |

| IL-13 | 2.05 | 3.31 | 0.04 | 0.50 |

| I-309 | 1.46 | 3.03 | 0.009 | 0.27 |

| TARC | 44.7 | 88.1 | 0.002 | 0.07 |

| SDF-1α | 944 | 1447 | 0.03 | 0.41 |

TABLE 4.

Cytokine Expression Change with the Development of Cetuximab-Associated Rash (n=37)

| Cytokine | Pre-Rash Mean [pg/mL] | Post-Rash Mean [pg/mL] | p-value (paired t-test) | Adj. p-value (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFα | 5.74 | 8.89 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| GRO | 417 | 698 | 0.02 | 0.40 |

| MDC | 1358 | 1952 | 0.04 | 0.40 |

| PDGF-α | 176 | 321 | 0.03 | 0.40 |

| PDGF-β | 3271 | 4600 | 0.04 | 0.40 |

| IL-33 | 88 | 60 | 0.03 | 0.40 |

Discussion

The addition of cetuximab to radiation therapy followed by cetuximab and irinotecan did not improve progression-free survival in children with HGA in this study based on predetermined statistical parameters. The 1-year median PFS of 18% is lower than historical controls including the recently published COG trials for newly diagnosed high-grade gliomas with a 1-year EFS rates of 38% and 49%5,6. This disparity could be influenced by differences in the extent of resection in the various series. While this trial was not designed to directly compare to other studies, it clearly did not meet the predetermined endpoint meriting further study and does not provide a therapeutic advantage to radiation therapy plus temozolomide with or without lomustine for pediatric HGA.5,6

In contrast, six patients with DIPG (28%) remained progression-free at the 1-year time-point meeting the predefined study criterion suggesting this regimen may be of benefit in this population. While the study met the predetermined 1-year PFS end-point for children with DIPG, over half of the patients still died within 1 year of diagnosis and the median PFS and OS were similar to recent DIPG trials.9,44 There was a single “outstanding responder” who was on study for over three years before ultimately progressing.

The combination of cetuximab with radiation therapy and irinotecan in this population was well tolerated. The toxicity was similar in this newly diagnosed population to the phase 1 heavily pretreated population31. Additionally, combining cetuximab with radiation did not result in increased or new toxicity. The rash/skin toxicity reported with cetuximab was also seen in this study. Rash occurrence was similar to the phase 1 study, occurring in 45 (77.8%) patients on this study and usually developing during the first few doses. However, the rashes seen were generally mild and responsive to supportive care; only three patients had grade 3 rash. There were seven patients who withdrew from study for parent preference, which may suggest that the time-consuming nature of this regimen or the side effects were undesirable to patients.

Cetuximab inhibits the EGFR pathway ligand-receptor binding but also has anti-tumor activity through activation of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).45 Pediatric HGA demonstrate EGFR over-expression often in the absence of gene amplification2,21,22 making this pathway a putative target in this population. We found that while 5 of the 19 patient samples analyzed had high-level gain consistent with amplification, this did not correlate with PFS or OS. Similar findings were seen in the adult HGA cetuximab trial.30 While K-RAS mutant status predicts lack of cetuximab efficacy in other cancers, 33,46 none of our patients had K-RAS gene mutations.

Gene microarray analysis on a subset of patients with HGA demonstrated that those with decreased E-cadherin and ERBB3 expression had prolonged survival compared with those patients with expression at the mean level or higher. High E-cadherin and ERBB3 expression has been identified as a potential biomarker of sensitivity to cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer.47 Low E-cadherin and ERBB3 expression are markers of a mesenchymal phenotype, 48 associated with EGFR activation in GBM.49 Given the small number of patients, this association with prolonged survival would need to be evaluated in a larger cohort. While this study did not aim to evaluate cetuximab’s ability to induce ADCC, the microarray analysis demonstrated up-regulation of genes involving immune activation, suggesting there was immune stimulation induced by this regimen. This may suggest a potential alternate mechanism of action of cetuximab.

Development of rash during EGFR-directed therapy correlates with increased likelihood of clinical response40 although the biological mechanisms are unclear. The rash often can be controlled by steroids or other immunosuppressive agents suggesting a role for systemic immune activation in this process.50 Our analyses were unable to demonstrate a group of pro-inflammatory cytokines that were significantly altered with the development of the rash with cetuximab. However, this may be due to the small sample size or cytokines profiled. Additionally, in contrast to patients with colorectal cancer, the development of rash was not associated with improved survival.40

The addition of an EGFR inhibitor to radiation and irinotecan may be an effective regimen for a portion of patients with newly diagnosed DIPG to provide longer progression-free survival. Further work with preclinical DIPG models is needed to elucidate the mechanism of this regimen’s anti-tumor effect. While this is a clinically tolerable regimen, it is time-intensive and difficult to recommend for further study in these tumors.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1: Putative Cetuximab Predictive Markers

Gene transcript panel of 45 putative cetuximab predictive markers screened in 9 tumor gene expression microarray profiles.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb; National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and P30CA046934 (University of Colorado Molecular Pathology Shared Resource to NF, AD, MK); National Institutes of Health K12 CA086913-08 to MM; Morgan Adams Foundation to NF, AD, MK; Grace’s Race to NF, AD, MK; Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation (AN)

The authors appreciate the contribution to this research made by E. Erin Smith, HTL(ASCP)CMQIHC of the University of Colorado Denver Research Histology Shared Resource. This resource and the Molecular Pathology Shared resource are supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA046934) to the University of Colorado.

Abbreviation

- DIPG

Diffuse Pontine Gliomaa

- HGA

High-grade astrocytomas

- POETIC

Pediatric Oncology Experimental Therapeutics Investigators’ Consortium

- EGFR

Epidermal growth Factor receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- ANC

absolute neutrophil count

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- PFS

progression-free survival

- TTP

time to progression

- OS

overall survival

- IV

intravenous

- EFS

event-free survival

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- FDR

false discovery rate

- CDH1

E-cadherin

- ERBB3

v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement: There are no conflicts of interest with regards to the agents discussed in this manuscript

This work was presented in part at the 2012 International Society of Pediatric Neuro Oncology (ISPNO) Meeting and at the 2013 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting.

Contributor Information

Margaret E. Macy, University of Colorado School of Medicine/Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Mark W. Kieran, Dana-Farber Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Harvard Medical School.

Susan N. Chi, Dana-Farber Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, Harvard Medical School.

Kenneth J. Cohen, Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins.

Tobey J. MacDonald, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta/Emory University School of Medicine.

Amy A. Smith, Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children.

Michael M. Etzl, Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

Michele C. Kuei, University of Colorado School of Medicine

Andrew M. Donson, University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Lia Gore, University of Colorado School of Medicine/Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Jennifer DiRenzo, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Tanya M. Trippett, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Irina Ostrovnaya, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Aru Narendran, Alberta Children’s Hospital.

Nicholas K. Foreman, University of Colorado School of Medicine/Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Ira J. Dunkel, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Ostrom QT, de Blank PM, Kruchko C, et al. Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation Infant and Childhood Primary Brain and Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol. 2015;16(Suppl 10):x1–x36. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, James CD, et al. Rarity of PTEN deletions and EGFR amplification in malignant gliomas of childhood: results from the Children’s Cancer Group 945 cohort. Journal of neurosurgery. 2006;105(5 Suppl):418–424. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.5.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suri V, Das P, Pathak P, et al. Pediatric glioblastomas: a histopathological and molecular genetic study. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11(3):274–280. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay JL, Boyett JM, Yates AJ, et al. Randomized phase III trial in childhood high-grade astrocytoma comparing vincristine, lomustine, and prednisone with the eight-drugs-in-1-day regimen. Childrens Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(1):112–123. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen KJ, Pollack IF, Zhou T, et al. Temozolomide in the treatment of high-grade gliomas in children: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(3):317–323. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakacki RI, Cohen KJ, Buxton A, et al. Phase 2 study of concurrent radiotherapy and temozolomide followed by temozolomide and lomustine in the treatment of children with high-grade glioma: a report of the Children’s Oncology Group ACNS0423 study. Neuro Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman CR, Farmer JP. Pediatric brain stem gliomas: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40(2):265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robison NJ, Kieran MW. Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a reassessment. J Neurooncol. 2014;119(1):7–15. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen KJ, Heideman RL, Zhou T, et al. Temozolomide in the treatment of children with newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(4):410–416. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandell LR, Kadota R, Freeman C, et al. There is no role for hyperfractionated radiotherapy in the management of children with newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic brainstem tumors: results of a Pediatric Oncology Group phase III trial comparing conventional vs. hyperfractionated radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43(5):959–964. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. Status of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Antagonists in the Biology and Treatment of Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(14):2787–2799. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Schmitz KR, Jeffrey PD, Wiltzius JJ, Kussie P, Ferguson KM. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(4):337–345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(11):1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kies MS, Holsinger FC, Lee JJ, et al. Induction chemotherapy and cetuximab for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results from a phase II prospective trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):8–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herbst RS, Kelly K, Chansky K, et al. Phase II selection design trial of concurrent chemotherapy and cetuximab versus chemotherapy followed by cetuximab in advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: Southwest Oncology Group study S0342. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4747–4754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.9356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frederick L, Wang XY, Eley G, James CD. Diversity and frequency of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in human glioblastomas. Cancer Res. 2000;60(5):1383–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Libermann TA, Nusbaum HR, Razon N, et al. Amplification, enhanced expression and possible rearrangement of EGF receptor gene in primary human brain tumours of glial origin. Nature. 1985;313(5998):144–147. doi: 10.1038/313144a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith JS, Tachibana I, Passe SM, et al. PTEN mutation, EGFR amplification, and outcome in patients with anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma multiforme. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(16):1246–1256. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.16.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbertson RJ, Hill DA, Hernan R, et al. ERBB1 is amplified and overexpressed in high-grade diffusely infiltrative pediatric brain stem glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(10 Pt 1):3620–3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bredel M, Pollack IF, Hamilton RL, James CD. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression and gene amplification in high-grade non-brainstem gliomas of childhood. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(7):1786–1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batchelor TT, Gilbert MR, Supko JG, et al. Phase 2 study of weekly irinotecan in adults with recurrent malignant glioma: final report of NABTT 97–11. Neuro Oncol. 2004;6(1):21–27. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santisteban M, Buckner JC, Reid JM, et al. Phase II trial of two different irinotecan schedules with pharmacokinetic analysis in patients with recurrent glioma: North Central Cancer Treatment Group results. J Neurooncol. 2009;92(2):165–175. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9749-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner CD, Gururangan S, Eastwood J, et al. Phase II study of irinotecan (CPT-11) in children with high-risk malignant brain tumors: the Duke experience. Neuro Oncol. 2002;4(2):102–108. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/4.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruber ML, Buster WP. Temozolomide in combination with irinotecan for treatment of recurrent malignant glioma. American journal of clinical oncology. 2004;27(1):33–38. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000045852.88461.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, 2nd, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(30):4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(28):4733–4740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prewett MC, Hooper AT, Bassi R, Ellis LM, Waksal HW, Hicklin DJ. Enhanced antitumor activity of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody IMC-C225 in combination with irinotecan (CPT-11) against human colorectal tumor xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(5):994–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neyns B, Sadones J, Joosens E, et al. Stratified phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(9):1596–1603. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trippett TM, Herzog C, Whitlock JA, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of cetuximab and irinotecan in children with refractory solid tumors: a study of the pediatric oncology experimental therapeutic investigators’ consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(30):5102–5108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, Cairncross JG. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8(7):1277–1280. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karapetis CS, Khambata-Ford S, Jonker DJ, et al. K-ras mutations and benefit from cetuximab in advanced colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(17):1757–1765. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moroni M, Veronese S, Benvenuti S, et al. Gene copy number for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and clinical response to antiEGFR treatment in colorectal cancer: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(5):279–286. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3798–3807. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kotoula V, Lambaki S, Televantou D, et al. STAT-Related Profiles Are Associated with Patient Response to Targeted Treatments in Locally Advanced SCCHN. Translational oncology. 2011;4(1):47–58. doi: 10.1593/tlo.10217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scartozzi M, Giampieri R, Maccaroni E, et al. Phosphorylated AKT and MAPK expression in primary tumours and in corresponding metastases and clinical outcome in colorectal cancer patients receiving irinotecan-cetuximab. Journal of translational medicine. 2012;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen P, Huang Y, Zhang B, Wang Q, Bai P. EphA2 enhances the proliferation and invasion ability of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Oncology letters. 2014;8(1):41–46. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffman LM, Donson AM, Nakachi I, et al. Molecular sub-group-specific immunophenotypic changes are associated with outcome in recurrent posterior fossa ependymoma. Acta neuropathologica. 2014;127(5):731–745. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Barni S. The predictive role of skin rash with cetuximab and panitumumab in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published trials. Target Oncol. 2013;8(3):173–181. doi: 10.1007/s11523-013-0257-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kellar KL, Kalwar RR, Dubois KA, Crouse D, Chafin WD, Kane BE. Multiplexed fluorescent bead-based immunoassays for quantitation of human cytokines in serum and culture supernatants. Cytometry. 2001;45(1):27–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20010901)45:1<27::aid-cyto1141>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Passam FH, Alexandrakis MG, Moschandrea J, Sfiridaki A, Roussou PA, Siafakas NM. Angiogenic molecules in Hodgkin’s disease: results from sequential serum analysis. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. 2006;19(1):161–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheskin D. Handbook of parametric and nonparametric statistical procedures. 3. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jennings MT, Sposto R, Boyett JM, et al. Preradiation chemotherapy in primary high-risk brainstem tumors: phase II study CCG-9941 of the Children’s Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(16):3431–3437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurai J, Chikumi H, Hashimoto K, et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mediated by cetuximab against lung cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(5):1552–1561. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller VA, Riely GJ, Zakowski MF, et al. Molecular characteristics of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma subtype, predict response to erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(9):1472–1478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cushman SM, Jiang C, Hatch AJ, et al. Gene expression markers of efficacy and resistance to cetuximab treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from CALGB 80203 (Alliance) Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(5):1078–1086. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Byers LA, Diao L, Wang J, et al. An epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene signature predicts resistance to EGFR and PI3K inhibitors and identifies Axl as a therapeutic target for overcoming EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(1):279–290. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Talasila KM, Soentgerath A, Euskirchen P, et al. EGFR wild-type amplification and activation promote invasion and development of glioblastoma independent of angiogenesis. Acta neuropathologica. 2013;125(5):683–698. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perez-Soler R, Saltz L. Cutaneous adverse effects with HER1/EGFR-targeted agents: is there a silver lining? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5235–5246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1: Putative Cetuximab Predictive Markers

Gene transcript panel of 45 putative cetuximab predictive markers screened in 9 tumor gene expression microarray profiles.