Abstract

Ageing is characterized by a decline in stem cell functionality leading to dampened tissue regeneration. While the expression of microRNAs across multiple species is markedly altered with age, the mechanism by which they govern stem cell-sustained tissue regeneration is unknown. We report that in the Drosophila testis, the conserved miR-9a is expressed in germline stem cells and its levels are significantly elevated during ageing. Transcriptome and functional analyses show that miR-9a directly regulates the expression of the adhesion molecule N-cadherin (N-cad). miR-9a null mutants maintain a higher number of stem cells even in the aged tissue. Remarkably, this rise fails to improve tissue regeneration and results in reduced male fertility. Similarly, overexpression of N-cad also results in elevated stem cell number and decreased regeneration. We propose that miR-9a downregulates N-cad to enable adequate detachment of stem cells toward differentiation, thus providing the necessary directionality toward terminal differentiation and spermatogenesis.

In the Drosophila testis, ageing leads to loss of germline stem cells. Here, the authors show that, during ageing in Drosophila, miR-9a is upregulated in male germline stem cells and regulates their proliferation by targeting N-cadherin.

Introduction

Ageing leads to reduced tissue homeostasis and a decline in the ability to replace damaged cells by new functional ones1. Homeostasis and repair of many adult tissues, such as blood, gut, and testis, are supported by small specialized populations of tissue-specific stem cells. In a given tissue, stem cells reside in a local microenvironment (niche) that acts as a control-unit to determine stem cell proliferation rate and protects the overall stem cell pool from depletion2.

In the Drosophila melanogaster (Drosophila) testis, mature sperm cells are generated by germline stem cells (GSCs) that are located at the apical tip of the testis. These cells, together with Cyst stem cells (CySCs) co-habitat in the niche and adhere around a cluster of somatic cells called the hub3–5. The hub is a spherical three-dimensional (3D) structure of approximately 12 cells, the great majority of which (Fig. 1a) (~9–10) are associated on several planes with all the surrounding stem cells. The GSCs are in direct contact with the hub via microtubule-based nanotubes that protrude directly into the hub6. The hub expresses signaling and adhesion molecules that maintain the stem cells within the niche. Upon GSC division, one of the two daughter cells remains adherent to the hub for self-renewal, while the other, a displaced progenitor cell, undergoes transit amplification divisions to generate spermatogonia progenitor cells before becoming a terminally differentiated spermatocyte7. GSCs have an age-dependent limited half-life of 14 days and are lost mainly via detachment from the niche8. In contrast, spermatogonia cells can dedifferentiate back into GSCs during ageing to repopulate the niche (Fig. 1a)9, 10, thus representing an intermediate cell population that can either differentiate or dedifferentiate according with the needs of the tissue. Therefore, although ageing results in significantly smaller testis with reduced cells of all types, unlike females, aged males (30-days) tend to remain fertile7, 11, 12. Nonetheless, since all testicular germ cells originate from a minute number of stem cells (approximately seven) even a small change in their overall number or division frequency is expected to impact tissue regeneration.

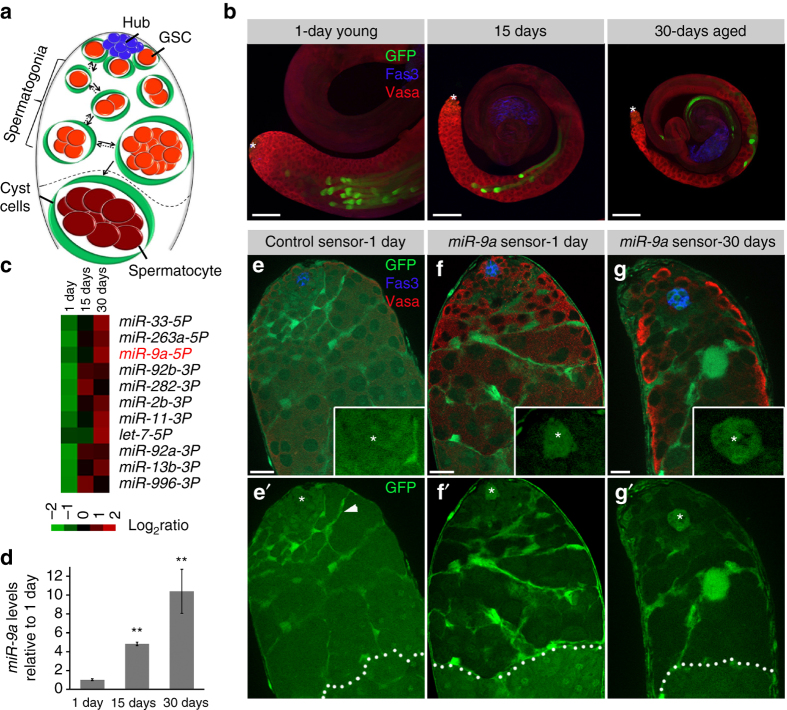

Fig. 1.

miR-9a increases during ageing and is expressed in GSCs and spermatogonia. a Side-view representation of the apical tip of the Drosophila testis. GSCs (red) are anchored to the hub (blue) and spermatogonia germ cells (red) can terminally differentiate to spermatocytes (crimson) or dedifferentiate to GSCs (two-directional arrows). GSCs and spermatogonia are encapsulated by cyst cells (green). Dashed-line separates spermatogonia from spermatocytes. b Testes from 1-day, 15-days, or 30-days-old males (green, mature sperms; Imp CB04573) immunostained for Vasa (red, germ cells) and Fas3 (blue, hub and seminal vesicles). Note an age-related decrease in cell numbers and in overall testis size. Scale bars, 100 µm. Asterisks mark the hub. c Heatmap of fold-change of Drosophila miRNAs in testes of 1-day, 15-days, or 30-days-old wild-type (w 1118) flies. Top 11 most age-altered miRNAs out of a total of 100 are shown. DESeq defined significance between 30-days and 1-day for each miRNA (P adj < 0.05; n = 2 replicas for each time point). d qRT-PCR for mature miR-9a relative to control (2S rRNA) in the testes of 1-day, 15-days, or 30-days-old wild-type (w 1118) males. Levels are normalized to 1-day-old adults. Error bars denote s.d. of three biological repeats each in triplicate measurements. Note a 10-fold increase of miR-9a in 30-days. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis was performed with Tukey multi-comparison test. **P ≤ 0.005 between 15 and 1-day and between 30 and 1-day. e–g’ Testes of control GFP sensor (e, e’) and miR-9a sensor 1-day (f, f’) and 30-days (g, g’) stained for Fas3 (blue) to mark the hub (asterisks), Vasa to mark the germ cells (red) and GFP (green). A control sensor is expressed in all cells at the apical tip of the testis including: hub, GSCs, CySCs, cyst cells (arrowhead), spermatogonia and spermatocytes. The miR-9a sensor detect endogenous levels of miR-9a in GSCs and spermatogonia. Dashed-line separates spermatogonia from spermatocytes. Note that miR-9a is not expressed in spermatocytes or the somatic niche (hub and cyst cells). All images in all figures are single sections. Scale bars, 10 µm

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are negative regulators of mRNA targets that prevent their translation into proteins. Recent data reveals that the levels of some miRNAs change with age across organisms, yet little is known about the molecular pathways that are regulated by these changes13. Here, we aimed to identify the miRNAs that change in the course of ageing and to find how these changes affect stem cell functionality. We found that miR-9a levels increase in the GSCs during ageing. Furthermore, miR-9a directly downregulates Neural-Cadherin (N-cad) to control the adhesion between GSCs and the hub, thus promoting GSCs detachment from the niche to allow differentiation and functional spermatogenesis.

Results

miR-9a levels increase in testis of aged males

To determine whether the levels of specific miRNAs are age-altered, we analyzed the miRNAome of testes dissected from 1-day (young), 15-days (mid-aged), and 30-days (aged) wild-type (w 1118) flies by NanoString technology (Fig. 1b, c). The resulting miRNAome showed that of a total of approximately 100 miRNAs, the expression level of a small cohort of 11 was elevated by more than two-folds in aged flies (Fig. 1c). The cohort included let-7 that was found to regulate GSCs niche ageing, thus supporting library reliability12. Interestingly, one of the top candidates identified was the evolutionary conserved miR-9a 14–17. miR-9a was also included in the top four most abundant miRNAs in the testis and in aged flies represents ~1% of the entire miRNAome. A subsequent qRT-PCR analysis revealed that compared to young males, miR-9a levels were increased by five-fold in testis of mid-aged males and by ten-fold in aged males (Fig. 1d).

miR-9a is expressed in GSCs and progenitor germ cells

To identify the cells that express miR-9a in the testis we used a green fluorescent protein (GFP) sensor that utilizes the unique property of miRNAs to silence protein expression18. The GFP-miR-9a sensor contains two repeats of the complementary sequence of miR-9a in an artificial 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) following a reporter GFP sequence15. Therefore, cells that endogenously express miR-9a create a silencing mechanism that prevents the expression of GFP. We used this method to compare the expression pattern of GFP-control and GFP-miR-9a sensor both driven under a tubulin promoter. GFP of the control sensor is expressed in all the cells of the testis, with a brighter signal in cyst cells as expected from high Tubulin expression in these long thin cells (Fig. 1e). However, in testes of both young and aged flies, the miR-9a sensor revealed that miR-9a is expressed in GSCs and spermatogonia progenitor germ cells. Moreover, miR-9a is not expressed in terminally differentiated spermatocytes, mature sperms, somatic cyst, and, notably, not in hub cells (Fig. 1f, g). Expressing miR-9a sensor in a miR-9a null mutant background of miR-9a[E39] 14 resulted in GFP expression in GSCs and spermatogonia cells, indicating that in the sensor flies GFP is specifically repressed by miR-9a in these cells (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). In support of these data, miR-9a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) shows that miR-9a is expressed in GSCs and spermatogonia and absent from the hub. Moreover, no miR-9a FISH signal was obtained in testis of miR-9a[E39] null mutants (Supplementary Fig. 1c–e).

miR-9a null present higher GSCs number with reduced division

To define the function of miR-9a in stem and progenitor germ cells, we compared the niche of young and aged miR-9a[E39] mutant males to age-matched controls. Immunofluorescence microscopy with germ and hub cell markers was used to evaluate the number of GSCs that are defined as germ cells that are physically attached to the hub11. Our analysis showed that compared to control (w 1118), miR-9a[E39] young mutants contain 37% more GSCs in their niche (Fig. 2a, b, m). Furthermore, these differences were maintained also in aged males, where miR-9a[E39] mutants showed 45% more GSCs (Fig. 2e, f, m). Similar to miR-9a[E39], a second miR-9a null allele, miR-9a[j22] 14, also maintains a high average number of GSCs in the niche of young and aged males (Supplementary Fig. 1f).

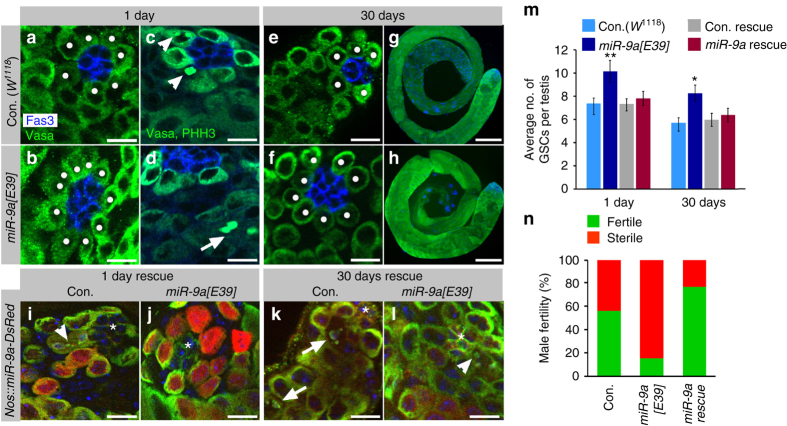

Fig. 2.

miR-9a mutants increase GSCs maintenance but reduce spermatogenesis. a–h Testes from 1-day (a, c) or 30-days (e, g)-old control (w 1118) or 1-day (b, d) or 30-days (f, h)-old miR-9a[E39] mutants immunostained for Fas3 (blue, hub), Vasa (green, germ cells), and with pHH3 (green, c–d). White dots denote GSCs. i–l Rescue of miR-9a[E39] mutants by ectopic expression of DsRed-miR-9a in GSCs and progenitor germ cells (nos-GAL4, UAS-DsRed-miR-9a; miR-9a[E39]), Con. rescue (nos-GAL4, UAS-DsRed-miR-9a; miR-9a[E39]/TM6), young (i) and aged (k); Vasa, Fas3, and pHH3 (green) DsRed (red) and DAPI (blue). Asterisks mark the hub, arrowhead denote mitotic GSCs and arrow mitotic spermatogonia. Scale bars 10 µm (a–f, i–l) and 100 µm (g–h). m Shown are average number of GSCs per testis along with 95% confidence interval (error bars). The total number of testes scored: con. (w 1118) 1-day (n = 47), 30-days (n = 60); miR-9a[E39] 1-day (n = 71), 30-days (n = 70); Con. rescue 1-day (n = 45), 30-days (n = 24); miR-9a[E39] rescue 1-day (n = 33), 30-days (n = 16); Statistical significance was determined as in Fig. 1d. **P ≤ 0.005, *P ≤ 0.01 between miR-9a[E39] and the other three genotypes (Con. w 1118, Con. rescue, and miR-9a [E39] rescue) of the same age. n Fertility assay of aged males (30 days) from control (w 1118, n = 36) and miR-9a[E39] mutants (n = 41), miR-9a[E39] rescue (n = 20). Note decreased fertility of aged miR-9a[E39] mutants and rescue in DsRed-miR-9a ectopic expression in GSCs and spermatogonia of the mutant background

To our surprise, the marked increase in GSCs number in miR-9a[E39] mutants did not result in improvement of the ageing phenotype. Similar to age-matched controls, testes of aged miR-9a[E39] mutants remained small, and presented with an even worse fertility phenotype; 85% miR-9a[E39] were sterile compared to 40% control (Fig. 2g, h, n). To determine why the increase in GSCs of miR-9a[E39] mutants does not improve spermatogenesis, we immunostained testes with anti-Thr 3-phosphorylated histoneH3 (pHH3) to mark mitotic cells (Fig. 2c, d) and counted pHH3-positive GSCs. In agreement with previous findings, the division frequency of young control GSCs was decreased from ~6% (13/223 GSCs) to ~3% (7/258 GSCs) in aged flies9. However, GSCs of miR-9a[E39] and miR-9a[J22] mutant alleles completely arrested division in aged flies (n = 233 and n = 178, respectively). Thus, although the niche of miR-9a null mutants consists of a higher number of GSCs, these cells fail to maintain spermatogenesis in aged males due to reduced division frequency.

To determine whether these mutant phenotypes are due to lack of miR-9a in GSCs and spermatogonia cells, we ectopically expressed UAS-DsRed-miR-9a 15 in these cells of miR-9a[E39] mutants (nos-GAL4, UAS-miR-9a-DsRed; miR-9a[E39]). DsRed fluorescent signal was used to mark the miR-9a-positive cells (Fig. 2i–l). This ectopic expression was sufficient to return the average number of GSCs associated with the hub back to normal numbers both in young and aged adults (Fig. 2m). Moreover, overexpression of miR-9a in miR-9a[E39] mutant regained GSCs division frequency to 3% (n = 102) and rescued fertility of the aged mutant males (Fig. 2n).

Identification of miR-9a targets in the testis

miRNAs repress mRNA translation, which is often followed by the mRNA deadenylation and decay19. Thus, the mRNA levels of direct miR-9a targets in the testis are expected to be elevated in miR-9a[E39] mutants. To facilitate miR-9a target identification we analyzed the transcriptome of cDNA libraries (Illumina) of four RNA samples (each in at least two biological repeats) prepared from testis of young (1-day), aged (30-days), control (w 1118), and miR-9a[E39] mutants. Reads were aligned to the Drosophila genome and gene expression levels were quantified using Htseq-count. This provided a list of 11,416 genes that are expressed in the testis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Differential gene analysis using edgeR-classic method provided count per million (CPM) values and P-values. After filtration based on log Fold Change (logFC ≥ 0.9), significance cutoff (P-value ≤ 0.05), and minimal CPM per each gene (≥1), we obtained a group of 450 genes that showed higher expression in young mir-9a[E39] mutant vs. control, and 446 genes that increased in old mutants vs. control. Of these, 231 genes showed higher expression in miR-9a[E39] mutant vs. control in both young and aged testis (Fig. 3a). A comparison of this list to the 194 in silico predicted miR-9a targets (Targetscan Fly) yielded six potential direct targets, one of which was senseless, a previously characterized target of miR-9a, confirming library reliability (Fig. 3a and Table 1)14, 17. However, antibody staining did not reveal the presence of senseless in the testis. Notably, the list also included N-cad, a typical member of the cadherin family of proteins that forms Ca+2-dependent homophilic interactions to mediate dynamic cell–cell adherent junction20. N-cad levels were significantly higher in testis of both young and aged miR-9a[E39] mutants compared to age-matched controls (Table 1). In contrast, the levels of Epithelial-cadherin (E-cad), an N-cad family member that is not a predicted miR-9 target, were unchanged (Table 1). At the apical tip of the testis N-cad is expressed both in the adherent junctions that connect hub cells to each other and in the junctions that connect GSCs to the hub11, 21.

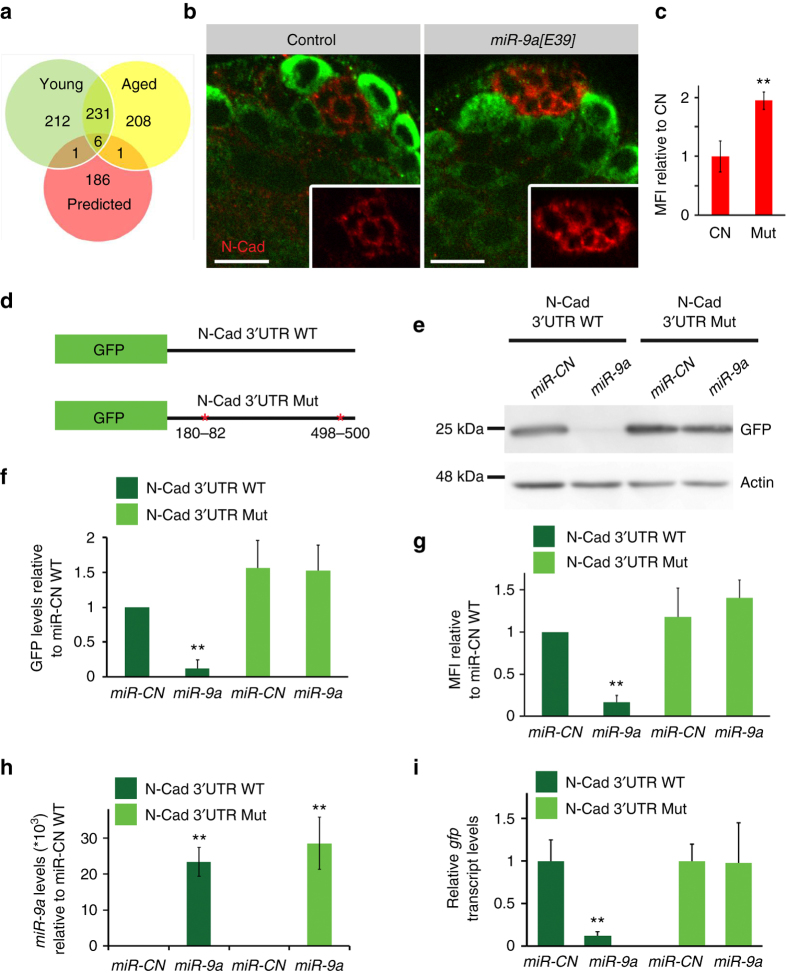

Fig. 3.

N-cad is a direct target of miR-9a. a Venn diagram of genes increased in testis from young (green) or aged (yellow) miR-9a[E39] mutants relative to age-matched controls transcriptome analysis in compare to computationally predicted miR-9a targets (red; http://www.targetscan.org/). b Representative images of testes taken at the same time exposure from control (w 1118; n = 45) and miR-9a[E39] mutants (n = 45) immunostained for N-cad (red) and Vasa (green; scale bars, 10 µm). c Immunofluorescence signal quantification. Note the significant increase in N-cad expression in GSCs-hub adherent junction of miR-9a[E39] mutants. P-values were generated after a two-tailed Student’s t-test (**P < 0.005). d–i miR-9a targets a gfp-N-cad-3′UTR reporter in S2R+ cells. d Schematic representation of GFP reporter constructs of N-cad 3′UTR WT or Mut (mutated bases to disrupt miR-9a seed pairing are indicated). e–f Western blot analysis of cells transfected with 50 nM miR-9a mimic or negative control miRNA (miR-CN) with GFP reporters of N-cad 3′UTR WT or Mut as indicated. e Shown is a representative immunoblot of n = 3 (biological repeats). f GFP quantification relative to actin (n = 3, biological repeats). g MFI of GFP from the GFP-positive cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 3, biological repeats). h,i qRT-PCR, average of n = 3, biological repeats (each in three replicas) for (h) mature miR-9a levels relative to miR-CN in N-cad 3′UTR WT. P-values were generated after a two-tailed Student’s t-test (**P < 0.005). i gfp transcript levels relative to miR-CN in N-cad 3′UTR WT

Table 1.

Six potential mRNA targets for miR-9a in the testis

| Gene | 1-day young | 30-days aged | Seeds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| logFC | Significance (P-value) | Average CPM per gene | logFC | Significance (P-value) | Average CPM per gene | ||||

| WT | Mir-9a mutant | WT | Mir-9a mutant | ||||||

| N-cad herin | 1.6 | 1.3E−26 | 20.7 | 63.4 | 0.9 | 4.9E−08 | 27.0 | 49.3 | 2 |

| sticks and stones | 1.2 | 1.08E−05 | 3.08 | 7.1 | 1.0 | 0.0005 | 2.57 | 5.23 | 1 |

| CG10512 | 1.5 | 5.25E−25 | 23.56 | 67.0 | 1.5 | 1.5E−22 | 41.29 | 115.62 | 1 |

| lame duck | 2.0 | 1.26E−09 | 1.02 | 4.2 | 1.1 | 0.0009 | 1.6 | 3.43 | 1 |

| meso18e | 1.3 | 7.35E−11 | 9.79 | 23.6 | 1.0 | 1.6E−6 | 11.9 | 23.5 | 1 |

| CG34136 | 1.5 | 0.0002 | 1.03 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 1.6E−6 | 0.7 | 3.1 | 1 |

| Senseless | 1.0 | 0.0001 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 1.0 | 0.001 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 1 |

| E-cad herin | 0.1 | 0.453 | 54.5 | 59.3 | 0 | 0.95 | 63.4 | 64.1 | 0 |

Transcriptome filtration based on logFC ≥ 0.9, significance cutoff (P-value ≤ 0.05), and minimal reading levels (sum reads per each gene ≥ 1) obtained a group of 231 genes that showed higher expression in mir-9a[E39] mutant vs. control in either young or aged testis. Comparison of this list to the predicted miR-9a targets resulted in the presented six candidates. The negative control, E-cad, is shown at the bottom of the table.

Validation of N-cad as a miR-9a target

Consistent with the transcriptome analysis, immunofluorescence staining of controls and mir-9a[E39] mutants with anti-N-cad revealed higher levels in adherent junction of mutants, among hub cells and between hub and GCSs (Fig. 3b). Examination of image Z-sections and a 3D projection revealed that the majority of hub cells generate N-cad boundaries with GSCs in several planes (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). Therefore, what may appear as an increase in N-cad among hub cells following miR-9a knockdown is in fact an increase that occurs mainly between hub and GSCs. Signal quantification of images taken at the exact same exposure showed a 1.9-fold increase of N-cad in mir-9a[E39] mutants compared to controls (Fig. 3c). In accordance with this observation, reducing N-cad levels in GSCs of the mir-9a[E39] mutant flies resulted in an overall reduction of N-cad expression (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d).

Two miR-9a canonical recognition sites are located within 3′UTR of N-cad (Targetscan Fly, Table 1 and Fig. 3d). Western analysis in Schneider 2 (S2R+) cells showed that miR-9a causes a 90% reduction in the expression of a GFP reporter containing the N-cad 3′UTR (gfp-N-cad-3′UTR WT). This effect was abolished by mutating the predicted target sites (gfp-N-cad-3′UTR Mut), indicating that seed mutations rendered the reporter resistant to translation inhibition (Fig. 3d–f). Consistent with these observations, flow cytometry (FACS) analysis of the GFP-expressing cells population revealed a marked 83% decrease in the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) when miR-9a was co-expressed with gfp-N-cad-3′UTR WT reporter (Fig. 3g). The transfection efficiency of miR-9a co-expression with gfp-N-cad-3′UTR WT or gfp-N-cad-3′UTR Mut reporters was measured by qRT-PCR for mature miR-9a, and confirmed similar expression levels (Fig. 3h). Moreover, miR-9a overexpression did not affect cell viability. Quantification of gfp by qRT-PCR revealed a 90% reduction in mRNA levels of the wild-type reporter only when miR-9a was co-expressed, with no effect on the mutant (Fig. 3i). These data confirm that miR-9a directly inhibits N-cad protein expression and destabilizes its mRNA through canonical sequences within the 3′UTR.

Misregulation of miR-9a in the stem cell niche

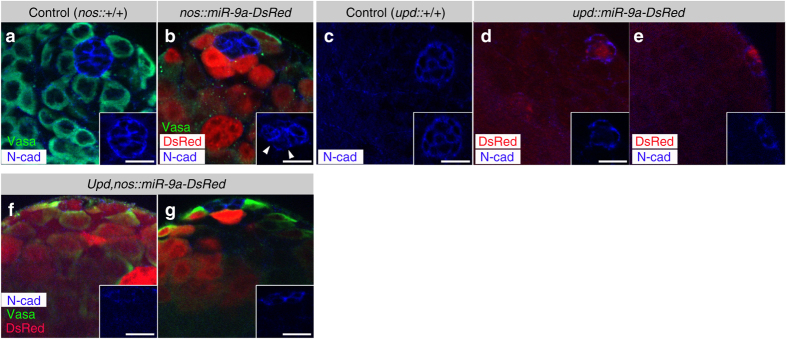

Given that miR-9a is expressed in GSCs and not in the hub, we tested the possibility that it regulates the adherent junctions between GSCs and hub cells via N-cad levels. We used UAS-miR-9a-DsRed 15 to overexpress miR-9a either in GSCs and spermatogonia cells (nos-GAL4; UAS-miR-9a-DsRed) or in the hub (upd-GAL4; UAS-miR-9a-DsRed), whereas the DsRed fluorescent signal marks the positive-expressing cells. miR-9a overexpression in GSCs and spermatogonia cells that normally express miR-9a resulted in fragmented N-cad expression in the adherent junctions between GSCs and hub cells (Fig. 4a, b). Moreover, ectopic expression of miR-9a-DsRed in hub cells, which do not express miR-9a in wild-type, was partial as only some of the testes expressed DsRed. However, all the samples where DsRed was detected (8/21) showed a dramatic decrease in N-cad expression in adherent junctions among hub cells (Fig. 4c–e). Simultaneous expression of UAS-miR-9a-DsRed in both the hub and GSCs (upd-GAL4; nosGAL4, UAS-miR-9a-DsRed) also caused a dramatic reduction in N-Cad expression (Fig. 4f). However, here too, clear detection of the DsRed signal in both hub and GSCs was only apparent in a few samples (14/39), while the rest of the samples expressed miR-9a-DsRed only in the germline (25/39, Fig. 4g). Together, these data suggest that miR-9a expression in GSCs regulates the dynamic adhesion between these cells and the hub.

Fig. 4.

miR-9a overexpression reduces N-cad. Ectopic expression of DsRed-miR-9a in GSCs and progenitor germ cells (a, b) or the hub (c–e) or in both the hub and GSCs (f, g) reduces N-cad expression. Testes detected for DsRed (red) and were stained with N-cad (blue) and Vasa (green). a, b Control (nos-GAL4 outcrossed to w 1118) and miR-9a overexpression in the GSCs and progenitor germ cells (nos-GAL4,UAS-DsRed-miR-9a). Note N-cad reduction between GSCs and hub cells (b and inset). c–e Control (upd-GAL4 outcrossed to w 1118) and miR-9a overexpression in the hub (upd-GAL4;UAS-DsRed-miR-9a). Note N-cad reduction between hub cells (d, e, and insets). f, g Simultaneous expression of miR-9a in both the hub and GSCs (upd-GAL4;nos-GAL4,UAS-DsRed-miR-9a). 36% of the testes showed DsRed-miR-9a both in the hub and germline (f, n = 39) and 64% showed DsRed-miR-9a only in the germline (g). Note a dramatic reduction of N-cad among hub cells and between hub and GSCs (f and inset). Scale bars 10 µm

N-cad overexpression in germline stem and progenitor cells

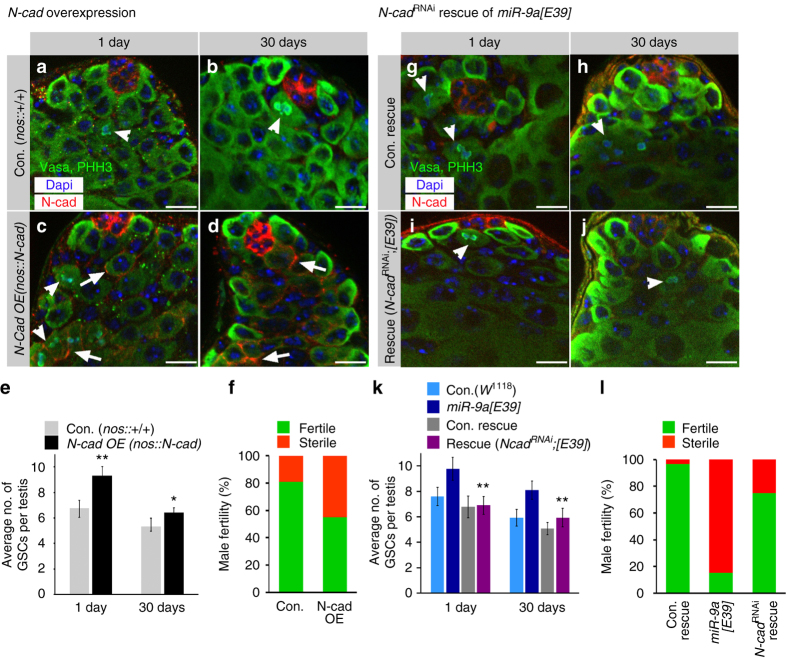

To determine whether N-cad overexpression presents a similar phenotype to that of miR-9a mutants, we measured the stem cell number, division frequency, and fertility of N-cad overexpressing flies in stem and spermatogonia germ cells (UAS-N-cad; nos-GAL4) compared to controls (nos-GAL4 outcrossed to w 1118). N-cad overexpression in young and aged males resulted in a significantly higher number of stem cells that were attached to the niche (Fig. 5a–e). However, GSC division frequency as measured by pHH3-positive cells was markedly reduced (0.7%) in aged N-cad overexpressing males (n = 277). Fertility tests showed that 45% of these flies are sterile compared to 19% of controls (Fig. 5f). Taken together, these findings indicate that the phenotype of miR-9a mutants origins at least partially from N-cad overexpression in stem cells.

Fig. 5.

N-cad overexpression mimics miR-9a[E39] phenotype and N-cadRNAi rescues miR-9a[E39] mutants. a–f Overexpression of N-cad in GSCs and progenitor germ cells (N-cad OE: nos-GAL4, UAS-N-cad) increases GSCs number but reduces their division frequency compared to control (Con.: nos-GAL4 outcrossed to w 1118). g–l N-cad RNAi in GSCs and progenitor germ cells of miR-9a[E39] mutants rescue mutant phenotype (rescue: nos-GAL4, UAS-N-cad RNAi; miR-9a[E39], Con. rescue: nos-GAL4, UAS-N-cad RNAi; miR-9a[E39]/TM6). a–d, g–j Representative images of testes immunostained for N-cad (red), Vasa and pHH3 (green) and DAPI (blue; scale bars 10 µm). Arrowheads denote mitotic germ cells and arrows denote N-cad ectopic expression (c–d). e, k Shown are average number of GSCs per testis along with 95% confidence interval (error bars). Statistical significance was determined as in Fig. 1d. e The total number of testes scored: Con. 1-day (n = 28) 30-days (n = 41); N-cad OE 1 -day (n = 35), 30-days (n = 41). P < 0.005 between N-cad OE and control in 1-day and P < 0.01 in 30-days. k The total number of testes scored: Con. (w 1118) 1-day (n = 23), 30-days (n = 35); miR-9a[E39] 1-day (n = 27), 30-days (n = 40). Con. rescue 1-day (n = 27), 30 days (n = 29); miR-9a rescue 1-day (n = 30), 30-days (n = 31). P < 0.005 between N-cad RNAi miR-9a[E39] rescue and miR-9a[E39] in young and aged males. f, l Fertility assay of aged males. f Con. (n = 21) and N-cad OE (n = 21). Note decreased fertility of aged N-cad overexpression. l Con. rescue (n = 29), miR-9a[E39] (n = 21), and N-cad RNAi miR-9a[E39] rescue (n = 24).Note that N-cad RNAi rescues miR-9a[E39] sterility

N-cadRNAi in GSCs rescues the miR-9a[E39] phenotype

Lastly, to directly address the possibility that the miR-9a[E39] mutant phenotypes of increased GSCs and decreased fertility are due to the presence of elevated N-cad at the hub-GSC junctions, we reduced its expression in GSCs of the mutants (nos-GAL4, UAS-N-cad RNAi; miR-9a[E39], Fig. 5g–l). This restored normal GSC number in both young and aged adults (Fig. 5k), regained normal division rate of GSCs in aged males (n = 178), and importantly rescued the age-related sterility of miR-9a[E39] mutants (Fig. 5l).

Discussion

In summary, our results suggest that miR-9a levels increase significantly in the testis during ageing to promote stem cell differentiation and detachment from their niche. While both young and aged miR-9a mutants hold a much higher number of stem cells in their niche, this does not improve spermatogenesis. On the contrary, GSC division frequency is reduced and spermatogenesis of miR-9a mutants is gradually decreased leading to premature sterility in aged males.

The appearance of high levels of N-cad in the niche of the miR-9a null mutants may be explained by the fact that GSCs are directly connected to the majority of the hub cells. Alternatively, it is possible that N-cad expression in the hub is non-autonomously regulated by N-cad levels or by other miR-9a targets in the GSCs. We present several lines of evidence to support that N-cad is a direct target of miR-9a. Two miR-9a binding consensus sites are located at the 3′UTR of N-cad to mediate translation inhibition and mRNA destabilization in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, our data suggest that at the apical tip of the testis miR-9a serves to disconnect GSCs from the hub by downregulating the expression of N-cad. GSCs adherent junctions are dynamic and constantly subjected to regulation. We propose that the differential expression of miR-9a in GSCs and progenitors, but not in hub cells, enables dynamic adherence of GSCs to the hub without affecting the hub cells themselves. We also suggest that the age-related increase in miR-9a levels correlates with the increase in dedifferentiation events of spermatogonia progenitors and possibly prevents accumulation of stem cells at the expense of spermatogenesis. In support of miR-9a as a negative regulator of adhesion are the findings that it represses two functionally orthologues of N-cad: in Drosophila the cadherin protein Flamingo (Fmi) and in mammals E-cad22, 23, suggesting that miR-9 plays a broad role in regulating cell–cell adhesion. Our transcriptome analysis revealed two additional adhesion proteins, Sticks and Stones and lame duck as potential targets of miR-9a (Table 1). Since N-cad is probably not the only mRNA target of miR-9a, it will be interesting to study whether these or other mRNA targets should be downregulated by miR-9a in order to regulate spermatogenesis during ageing.

In conclusion, we propose that the increase in miR-9a during ageing in stem and progenitor germ cells modulates degeneration in spermatogenesis and promotes detachment toward sperm maturation. The abnormal increase in stem cell maintenance in miR-9a mutant testis and the age-related loss of fertility illustrate the severe consequences of failure to restrain stem cell adherence to their niche.

Methods

Drosophila stocks, ageing, and fertility

Flies were raised at 25 °C on standard cornmeal molasses agar medium freshly prepared in our lab. Young flies were selected upon hatching and dissected in the first 3 days of their life. Young flies designated for ageing were placed in vials (20 males and 20 females per vial) that were replaced three times a week to prevent second generation from hatching and adult fly loss. Middle-aged flies were dissected at 15 days and aged flies at 30 days. Control and experiments were aged and tested at the same time. Fertility assays of aged males were performed by mating single males of each genotype (n ≥ 21) with three wild-type (w 1118) virgin females. Males in vials that did not contain progeny were defined as sterile.

Fly strains used in this research were w 1118, control GFP sensor (S.M. Cohen18), miR-9a-GFP sensor (E.C. Lai)15, upd-GAL4 (T. Xie), sco/cyo; nos-Gal4:VP16/MKRS (M. Van Doren24), nos-GAL4/Cyo;Sb/Tm6b (E. Arama), Imp CB04573 (A. Spradling25), UAS-DsRed-miR-9a (E.C. Lai)15, UAS-DN-cadherin on 2nd (T. Uemura26), UAS-N-Cad RNAi (2nd Chr. VDRC #1092). miR-9a null mutant alleles (miR-9a[E39] (a backcrossed line) and miR-9a[J22]) were generated in Prof. Gao’s lab by ends-out homologous recombination that replaced the 78 nt-long miR-9a precursor with the white gene14. To obtain identical genetic backgrounds that are critical for ageing experiments27, miR-9a[E39] flies were first outcrossed in our lab to w 1118. The siblings obtained (miR-9a[E39]/+) were then crossed again to obtain the miR-9a[E39]. Homozygosity was confirmed by the wing phenotype15, 14 and PCR.

Immunofluorescence

Whole-mount testes from adult Drosophila were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and placed in Terasaki plates in10 µl fix solution of 2% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PLP buffer (0.075 M lysine, 0.01 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature, rinsed and washed twice in PBST (0.5% Triton X-100), followed by standard immunofluorescence staining. Primary antibodies used in this study were as follows: polyclonal rabbit anti-Vasa (Santa Cruz d-260, 1:200), rabbit anti-pHH3 (Merck Millipore 06-570, 1:200). Mouse anti-Fas3 (7G10, 1:10) and rat anti-DN-cad (DN-Ex #8, 1:5) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at University of Iowa. Secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. Samples were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories). Images were taken on a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope equipped with an Apotome system using the AxioVison software and were processed by Adobe Photoshop CS6.

Stem cell counting and division frequency

GSCs were counted as Vasa-positive cells that were in direct contact with the hub that was marked with anti-Fas3 or anti-DN-cad. Sample size of n ≥ 20 testes was selected in preliminary studies to represent the average GSCs number and is indicted per each genotype and age. GSCs division frequency was calculated as the percentage of the total number of GSCs pHH3-positive cells from the overall GSCs number that were scored. For each study, results from more than 20 testes were pooled and averaged.

miR-9a FISH

Whole-mount testes were dissected in PBS diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) and placed in Terasaki plates in 10 µl fix solution of 4% PFA in PBT buffer (PBS DEPC, 0.1% Tween-20) for 20 min at room temperature, rinsed and washed twice in PBTH (PBT, 50 µg/ml Heparin, and 250 µg/ml tRNA). Samples were rinsed once in Proteinase K buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaCl) and incubated for 3 min in 1 µl proteinase K diluted in Proteinase K buffer (20 mg/ml). Following washes in PBT samples were re-fixed and washed. Samples were then washed in Exiqon hybridization buffer and incubated for 1 h at 55 °C with 40 mM xtr-mir-9a-5p 5′ and 3′Dig labeled LNA probe (619314-360, Exiqon). Samples were then washed in serial dilutions of SSC buffer (5×, 1×, and 0.2× SSC) and blocked with TNB buffer (TSA Fluorescence Kit, PerkinElmer). Following overnight incubation with anti-DIG-POD antibody (Roche), signal was amplified with TSA Cyanine-3 and testes were mounted with DAPI.

RNA extraction

Testes of 100 flies (~200 testes) of each phenotype young and aged were dissected in PBS DEPC. Testes were collected and pooled in 100 µl TRIzol® Reagent and stored at −80 °C until future RNA extraction. To maximize RNA extraction, frozen samples were thawed at 37 °C and re-frozen in liquid nitrogen (−80 °C) five times, followed by five cycles of 30 s vortex and rest. Then 100 µl of 99% ethanol was added and the samples and total RNA was extracted using Direct-zol™ RNA miniprep kit (ZYMO Research) with DNase treatment, according to the manufacture instructions. The RNA was eluted in 50 µl of pre-heated DNase and RNase free water and kept in −80 °C for future use. RNA quality was measured by a bioanalyzer and samples were used for miRNAome, transcriptome, or qRT-PCR.

RNA extraction from S2R+ cells was obtained by Quick-RNA™ Miniprep kit (ZYMO Research), according to manufacture instructions. RNA was kept in RNase-DNase free water in −80 °C for until qRT-PCR analysis.

Transcriptome analysis and statistics

Illumina cDNA libraries were prepared from 1 µg total RNA extracted from testes of young and aged control w 1118 and miR-9a[E39] backcrossed mutants with TruSeq RNA V2/Illumina kit. Libraries were sequenced with Illumina HiSeq 2500. Raw reads were filtered for Illumina adapters and low-quality reads using Trimmomatic. Filtered reads were aligned to the Drosophila genome (dm6, FlyBase 6.05) using STAR (settings --alignIntronMax = 25,000 --genomeSAindexNbases = 9.15 --sjdbGTFfile). Gene expression levels were quantified using htseq-count, and differential expression was analyzed using edegR. Differential expression data were filtered based on logFC ≥ 0.9, significance cutoff (P-value ≤ 0.05), and minimal reading levels (CPM ≥ 1). A group of genes that showed higher expression in mir-9a[E39] mutant vs. control in both young and aged testis was compared to a list of in silico predicted mir-9a targets (Targetscan Fly, http://www.targetscan.org/).

miRNAome analysis and statistics

Total purified RNA samples (0.5 µg at 100 ng/µl) of young, mid-aged, and aged w 1118 were used to determine the identity and levels of miRNAs with nanoString Technologies (nCounter fly miRNA expression kit). Raw data were normalized using the nCounter software and differential expression was analyzed using DESeq.

Generation of DNA constructs

The nucleotide numbers of the following sequences refer to their numbers in the 3′UTRs as shown on FlyBase. N-cad 3′UTR was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA with forward primer: N-cad3′UTR_Xho1: CCGCTCGAGGCTGGTGGAGCGAGCAGTGATGAG, and reverse primer: N-cad 3′UTR_HInd3: CCCAAGCTTGCGCTCCTAAACTAAACTTTGGTATGCTCTC. PCR fragment was ligated into pGEM T Easy vector. To generate pGEM-N-cad 3′UTR-Mut nucleotides 180–182 (180CAA = TGG; Mut1) and 498–500 (180CAA = TGG; Mut2) were mutated by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) with primers: nCad_3UTR_Mut1_For: CACACACACAAAGAAAGCGCAACTGGAGAAGCATCTCAATGCTG and nCad_3UTR_Mut1_Rev: CAGCATTGAGATGCTTCTCCAGTTGCGCTTTCTTTGTGTGTGTG, and nCad_3UTR_Mut2_For: GATTTGTATGATGTAGGAGAGAGCATACTGGAGTTTAGTTTAGGAGCGC and nCad_3UTR_Mut2_Rev: GCGCTCCTAAACTAAACTCCAGTATGCTCTCTCCTACATCATACAAATC. pAc5-eGFP was a gift from D. Ideses (T. Juven-Gershon Lab) in which eGFP ORF was ligated via EcoRI and NotI into pAc5.1. N-cad-3′UTRWT or Mut was digested from pGEM with Xho1 and HInd3 and ligated into pAc5-eGFP to generate pAc-gfp-N-cad-3′UTRWT or Mut that were used for transfection in S2R+ cells. The sequence of all DNA constructs described above was verified by DNA sequencing.

S2R+ cell culture and transfection

S2R+ adherent cells (T. Guven-Gershon) were cultured in Schneider’s Drosophila medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries Inc.) and 1% Penicillin Streptomycin. Each experiment was done at least in three biological repeats and each transfection was performed in triplicate. 600k cells were seeded in 24-well plates. pAc-GFP reporter plasmids (0.5 µg DNA per well) and dm-miR-9a mimic or negative control miR (10 nM; Applied Biosystems) were co-transfected according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (LipoJet™). Post 48 h transfection cells were collected for flow cytometry, RNA/protein extraction.

Flow cytometry

Cells were washed twice and resuspended in 200 μl PBS. The samples were analyzed using BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer with DACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Gates were set to exclude necrotic cells and cellular debris, and the fluorescence intensity of events within the gated regions was quantified. Data were collected from 10,000 events for each sample.

Western blotting

Cells were washed twice in PBS and total cell proteins were lyse with 1× Laemmli buffer. Proteins were separated on 12.5% SDS–PAGE gels, followed by western blotting according to standard procedures. Nitrocellulose membranes containing protein cell lysate incubated with primary antibodies at a dilution of 1:2000 rabbit anti-GFP (Cell Signaling; 2956) and 1:5000 mouse anti-Beta Actin (Sigma A5441). Proteins were visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit for horseradish peroxidase (Biological Industries) and quantified using a CCD camera and Image-J software. The uncropped western blot can be found in Supplementary Fig. 4.

qRT-PCR and statistics

1 µg RNA was treated with DNaseI (Promega) and reverse-transcribed with random hexamer mixture and the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific), according to the manufacture instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with a StepOnePlusTM Real-time PCR System using TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems). Relative gfp (assay ID: Mr04329676_mr) levels were compared to Ribosomal Protein L32 (RPL-32; assay ID: Dm02151827_g1). For miRNA analysis 10 ng RNA was used to prepare cDNA with TaqMan miRNA-specific reverse-transcription primers (Applied Biosystems) for miR-9a (Mir-9 assay ID: 000583) and ribosomal RNA 2S (V00236). Real-time PCR results were analyzed using StepOne software (Applied Biosystems) and significance was determined using Student’s t-test. An average of three experiments (each performed in triplicate measurements) is shown (mean ± s.d.). P-values were generated after a two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare ΔC T between time points or genotypes across three independent biological replicates.

Statistics

For quantification of GSCs number and for densitometric analysis of pixel intensity, the mean ± 95% confidence interval and the number (n) of testes examined are shown. P-values were generated after a two-tailed Student’s t-test or determined by one-way ANOVA, and post hoc analysis was performed with Tukey multi-comparison test if samples are normally distributed and have equal variances, **P ≤ 0.005 and *P ≤ 0.01.

Data availability

The transcriptome and miRNAome data have been deposited in Dryad Digital Repository (Epstein et al. 2017): DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.30cn0.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to F.B. Gao, E.C. Lai, S.M. Cohen, S.F. Önel, T. Uemura, D. Ideses, T. Juven-Gershon, H.J. Bellen, O. Schuldiner, N. Issman, K. Yacobi-Sharon, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for gracious gifts of Drosophila stocks, plasmids, and antibodies that were critical for this study. We thank N. Sher and the Bioinformatics unit of University of Haifa for transcriptome analysis. We also thank L. Barki-Harrington, D. Ideses, and H. Kaspi for advices and comments. This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) personal grant (1510/14), the Binational Science Foundation (BSF)- USA-Israel (2015398) and by Victoria and Marvin Sadowski Fund (Canada).

Author contributions

Y.E., N.P., M.V., M.Z.F., R.B., L.P.K., and H.T. designed and carried out the experiments and interpreted the results. H.T. wrote the manuscript. N.P. and M.V. corrected the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00485-9.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rando TA. Stem cells, ageing and the quest for immortality. Nature. 2006;441:1080–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature04958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones DL, Wagers AJ. No place like home: anatomy and function of the stem cell niche. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:11–21. doi: 10.1038/nrm2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiger AA, Jones DL, Schulz C, Rogers MB, Fuller MT. Stem cell self-renewal specified by JAK-STAT activation in response to a support cell cue. Science. 2001;294:2542–2545. doi: 10.1126/science.1066707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tulina N, Matunis E. Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science. 2001;294:2546–2549. doi: 10.1126/science.1066700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leatherman JL, Dinardo S. Germline self-renewal requires cyst stem cells and stat regulates niche adhesion in Drosophila testes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:806–811. doi: 10.1038/ncb2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inaba M, Buszczak M, Yamashita YM. Nanotubes mediate niche-stem-cell signalling in the Drosophila testis. Nature. 2015;523:329–332. doi: 10.1038/nature14602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Insco ML, Leon A, Tam CH, McKearin DM, Fuller MT. Accumulation of a differentiation regulator specifies transit amplifying division number in an adult stem cell lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:22311–22316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912454106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallenfang MR, Nayak R, DiNardo S. Dynamics of the male germline stem cell population during aging of Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2006;5:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng J, et al. Centrosome misorientation reduces stem cell division during ageing. Nature. 2008;456:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature07386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brawley C, Matunis E. Regeneration of male germline stem cells by spermatogonial dedifferentiation in vivo. Science. 2004;304:1331–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.1097676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle M, Wong C, Rocha M, Jones DL. Decline in self-renewal factors contributes to aging of the stem cell niche in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:470–478. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toledano H, D’Alterio C, Czech B, Levine E, Jones DL. The let-7-Imp axis regulates ageing of the Drosophila testis stem-cell niche. Nature. 2012;485:605–610. doi: 10.1038/nature11061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg D, Cohen SM. miRNAs and aging: a genetic perspective. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014;17:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Wang F, Lee JA, Gao FB. MicroRNA-9a ensures the precise specification of sensory organ precursors in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2793–2805. doi: 10.1101/gad.1466306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bejarano F, Smibert P, Lai EC. miR-9a prevents apoptosis during wing development by repressing Drosophila LIM-only. Dev. Biol. 2010;338:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biryukova I, Asmar J, Abdesselem H, Heitzler P. Drosophila mir-9a regulates wing development via fine-tuning expression of the LIM only factor, dLMO. Dev. Biol. 2009;327:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassidy JJ, et al. miR-9a minimizes the phenotypic impact of genomic diversity by buffering a transcription factor. Cell. 2013;155:1556–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djuranovic S, Nahvi A, Green R. miRNA-mediated gene silencing by translational repression followed by mRNA deadenylation and decay. Science. 2012;336:237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.1215691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brasch J, Harrison OJ, Honig B, Shapiro L. Thinking outside the cell: how cadherins drive adhesion. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Bras S, Van Doren M. Development of the male germline stem cell niche in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2006;294:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma L, et al. miR-9, a MYC/MYCN-activated microRNA, regulates E-cadherin and cancer metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:247–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Wang H, Li X, Li Y. Epithelial microRNA-9a regulates dendrite growth through Fmi-Gq signaling in Drosophila sensory neurons. Dev. Neurobiol. 2016;76:225–237. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Doren M, Williamson AL, Lehmann R. Regulation of zygotic gene expression in Drosophila primordial germ cells. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:243–246. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buszczak M, et al. The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics. 2007;175:1505–1531. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwai Y, et al. Axon patterning requires DN-cadherin, a novel neuronal adhesion receptor, in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Neuron. 1997;19:77–89. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Partridge L, Gems D. Benchmarks for ageing studies. Nature. 2007;450:165–167. doi: 10.1038/450165a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The transcriptome and miRNAome data have been deposited in Dryad Digital Repository (Epstein et al. 2017): DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.30cn0.