Abstract

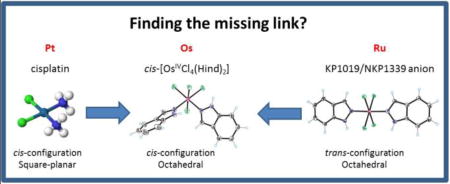

The relationship between cis-trans isomerism and anticancer activity has been mainly addressed for square-planar metal complexes, in particular, for platinum(II), e.g., cis- and trans-[PtCl2(NH3)2], and a number of related compounds, of which, however, only cis-counterparts are in clinical use today. For octahedral metal complexes, this effect of geometrical isomerism on anticancer activity has not been investigated systematically, mainly because the relevant isomers are still unavailable. An example of such an octahedral complex is trans-[RuCl4(Hind)2]−, which is in clinical trials now as its indazolium (KP1019) or sodium salt (NKP1339), but the corresponding cis-isomers remain inaccessible. We report the synthesis of Na[cis-OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] (Na[1]) to show that cis-isomer of NKP1339 can in principle be prepared as well. The procedure involves heating (H2ind)[OsIVCl5(κN1-2H-ind)] in a high boiling point organic solvent resulting in an Anderson rearrangement with formation of cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([1]) in high yield. The transformation is accompanied by an indazole coordination mode switch from κN1 to κN2 and stabilization of the 1H-indazole tautomer. Fully reversible spectroelectrochemical reduction of [1] in acetonitrile at 0.46 V vs NHE is accompanied by a change in electronic absorption bands indicating formation of cis-[OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2]− ([1]−). Chemical reduction of [1] in methanol with NaBH4 followed by addition of nBu4NCl afforded the osmium(III) complex nBu4N[cis-OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] (nBu4N[1]). Metathesis reaction of nBu4N[1] with an ion exchange resin led to isolation of the water-soluble salt Na[1]. The X-ray diffraction crystal structure of [1]·Me2CO was determined and compared with that of trans-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)]·2Me2SO (2·2Me2SO), also prepared in this work. EPR spectroscopy was performed on the OsIII complexes and the results analyzed by ligand-field and quantum chemical theories. We furthermore assayed effects of [1] and Na[1] on cell viability and proliferation in comparison to trans-[OsIVCl4(κN1-2H-ind)] [3] and cisplatin and found a strong reduction of cell viability at concentrations between 30 and 300 µM in different cancer cell lines (HT29, H446, 4T1 and HEK293). HT-29 cells are less sensitive to cisplatin than 4T1 cells, but more sensitive to [1] and Na[1], as shown by decreased proliferation and viability as well as an increased late apoptotic/necrotic cell population.

Keywords: Osmium(IV), osmium(III), 1H-indazole, cis/trans isomerism, solvatochromism, antiproliferative activity, EPR spectra

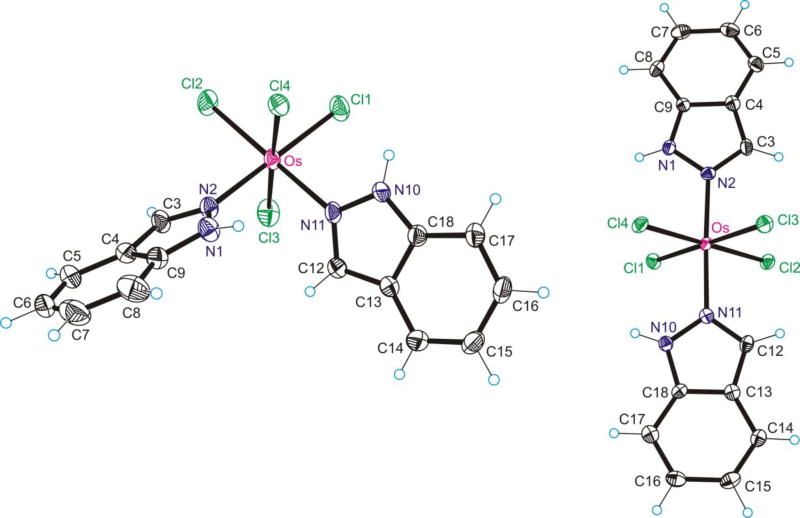

For Table of Contents Only

The synthesis and characterization of unprecedented cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] and Na[cis-OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] is reported. Even though the analogous cis-isomers of trans-RuIII complexes KP1019/NKP1339 remain unknown, their synthesis appears to be imminent giving an opportunity that deserves to be exploited in the search for more effective metal-based anticancer drugs than those currently in clinical trials.

Introduction

Indazole derivatives are characterized by a variety of applications as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, antiprotozoal, antiobesity, and antifungal agents.1, 2, 3 They have been found to be active as inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase (NOS),4 bacterial gyrases,5 hydrolases,6 and various kinases.7, 8, 9 The ruthenium(III) complexes H2ind[trans-RuCl4(κN2-1H-indazole)2] (KP1019) and Na[trans-RuCl4(κN2-1H-indazole)2] (NKP1339) are in clinical trials as potential anticancer agents.10 Indazole, usually referred to as 1H-indazole, exists in three tautomeric forms (Chart 1). The 1H-indazole is the dominant tautomer in the gas phase and aqueous solution,11, 12 as well as in metal complexes, however, some substituted organic 2H-indazoles are known13 as well as rare, inorganic examples such as an organoruthenium(II) complex with 2-methyl-indazole,14 and the osmium(IV) complexes trans-[OsIVCl4(κN1-2H-ind)2],15 and (H2ind)[OsIVCl5(κN1-2H-ind)].16 The synthesis of the latter complex along with (H2ind)[OsIVCl5(κN2-1H-ind)] made an estimation of the effect of indazole tautomer identity on the antiproliferative activity of osmium(IV) complexes in different human cancer cell lines possible.

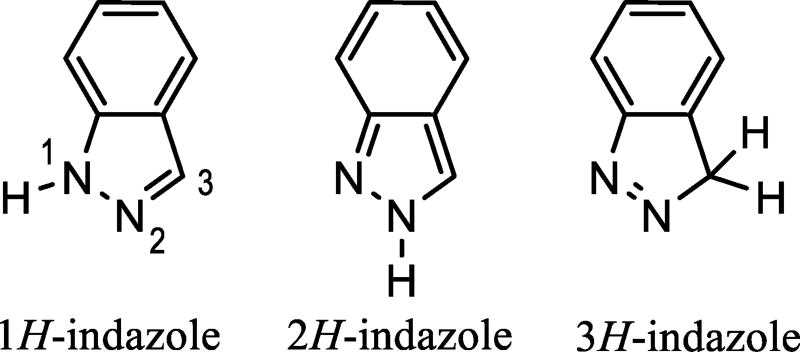

Chart 1.

The tautomers of indazole, with ring numbering given on left tautomer.

After the discovery of the antiproliferative activity of cisplatin in 1965,17 the cis-geometry was long believed to be a prerequisite for the anticancer activity of metal compounds.18, 19 Even though this situation changed over the years as several trans-isomers were synthesized and discovered to exhibit higher antiproliferative potency than their cis-congeners,20 with some of them having the advantage of not showing cross resistance to cisplatin,21 there are no trans-isomers in clinical use today. However, all these examples are dealing with square-planar metal complexes. The importance of cis-trans isomerism in octahedral coordination complexes has been known since Alfred Werner’s time.22 In the case of octahedral ruthenium and osmium compounds, some cases of isomeric pairs are well-documented for azole heterocycles23, 24 and bis-picolinamide ruthenium(III) dihalide complexes.25 The structurally related osmium(III) pyridine derivatives, cis- and trans-[OsCl4(Py)2]− are also known, and both were crystallographically characterized.26 Overall, the number of cytotoxic Werner’s type osmium complexes is increasing.27 However, elucidation of structure-activity relationship remains an important task for the understanding of the mode of action of such complexes and development of more effective anticancer agents than those exploited today.

Following our interest in investigation of the chemistry of osmium(IV)-indazole-tautomer interconversion, we studied the isomerization mechanism of nBu4N[OsIVCl5(κN1-2H-ind)] into nBu4N[OsIVCl5(κN2-1H-ind)] and the results will be reported in due course. In addition, it was found that prolonged heating of (H2ind)[OsIVCl5(κN1-2H-ind)] in the high boiling point solvent 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane afforded an unprecedented product of cis-configuration, namely cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([1]).

The present study of [1] adds to the growing family of osmium(IV) and osmium(III) azole compounds.28 The complexes presented in this work are stable in aqueous and/or Me2SO solution for at least 24 h (osmium(III) compounds in the absence of air oxygen). Upon one-electron reduction of the metal center the tautomer coordinated to metal remains intact as also reported for trans-[OsIIICl4(κN1-2H-ind)2]−.29 Quite recently, a pH dependent indazole tautomerization was reported, wherein stabilization of one of the tautomers was achieved by coordination of an indazole-pendant azamacrocyclic scorpiand to CuII or ZnII.30

Herein, we describe the synthesis of cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([1]) and its one electron reduced species (nBu4N)[1] and Na[1] (Chart 2). These complexes are spectroscopically characterized, in particular by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), which technique has been shown to be very useful in unravelling the solution structure of RuIII anti-cancer drug candidates,31 as well as other RuIII complexes.32 EPR has been less widely applied to OsIII complexes of any type because of the paucity of such compounds and frequently their inherently more challenging experimental EPR properties.33, 34 In addition, the antiproliferative activity of the two octahedral cis-isomers [1] and Na[1], along with the X-ray diffraction structures of cis- and trans-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([1] and [2], respectively) are reported. This discovery offers the pathway to cis-isomers of investigational anticancer drugs KP1019 and NKP1339 and a subsequent opportunity to investigate structure-activity relationships for octahedral cis/trans-[RuCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2]− isomers.

Chart 2.

Compounds reported in this work. Underlined numbers indicate compounds studied by single crystal X-ray diffraction. Complex [3] relevant to this work was reported previously.15

Experimental Section

Materials

OsO4 (99.8%) was purchased from Johnson-Matthey, while nBu4NBr, NaBH4, 1H-indazole, KBr and Dowex Marathon C-resin Na+ form were from Sigma-Aldrich. All chemicals were used without further purification.

Synthesis of osmium complexes

The starting compounds (H2ind)[OsCl6] and (H2ind)[OsCl5(κN1-2H-ind)] were prepared according to literature protocols.35, 16

cis-[OsCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2]·Me2CO ([1]·Me2CO)

(H2ind)[OsCl5(κN1-2H-ind)] (160 mg, 0.26 mmol) was stirred in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (30 ml) at 128 °C for 10 h. Removal of the solvent at reduced pressure, washing the residue with diethyl ether and drying in vacuo afforded a black solid of [1]. Yield: 140 mg, 93%. Elemental analysis was performed on a sample crystallized from Me2CO. Calcd for C14H12Cl4N4Os·Me2CO (Mr = 626.39), %: C, 32.60; H, 2.90; N, 8.94; O, 2.55. Found, %: C, 32.83; H, 2.89; N, 8.88; O, 2.57. Analytical data for 1: HRMS (positive) in MeOH: m/z 532.9713 [OsCl3(Hind)2]+; calcd m/z 532.9652. ESI-MS in MeOH (negative): m/z 567 [OsIVCl4(Hind)2–H]−. MIR, cm−1: 641, 747, 784, 800, 964, 1000, 1079, 1239, 1360, 1467, 1515, 1627, 2928, and 3314. UV–vis (Me2CO), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 371 (1632), 406 (1704), 582 (410), 729 (130). UV–vis (acetonitrile), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 228 (2663), 268 (2660), 364 (1663), 405 (1635), 510 sh, 613 (508), 726 (116). UV–vis (chloroform), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 243 (1228), 271 (1413), 286 sh, 365 (740), 409 (853), 559 (220), 725 (82). UV–vis (DMF), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 286 (2686), 369 (1727), 400 (1636), 507 (683), 614 (530), 726 (175). UV–vis (Me2SO), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 273 (2900), 285 (2865), 364 (1533), 407 (1600), 618 (521), 724 (137). UV–vis (ethanol), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 370 (1665), 402 (1663), 562 (376), 608 sh, 725 (96). UV–vis (THF), λmax, nm (ε, M−1 cm−1): 296 (2423), 374 (1677), 400 (1797), 543 (364), 726 (83). 1H NMR (Me2SO-d6, 500.26 MHz), δ: −9.42 (s, 2H, H3), 1.35 (t, J = 7.96 Hz, 2H, H6), 4.66 (d, J = 8.98 Hz, 2H, H4), 8.04 (t, J = 8.06 Hz, 2H, H7), 10.87 (d, 2H, H5, J = 8.23 Hz), 16.49 (s, 2H, H3) ppm. 13C{1H} NMR (Me2SO-d6, 125.82 MHz), δ: 69.29 (C8 or C9), 69.97 (C8 or C9), 74.78 (C5), 101.66 (C7), 143.40 (C4), 177.94 (C6), 189.05 (C3) ppm. Suitable crystals for X-ray diffraction study were grown by slow evaporation of a solution of [1] in Me2CO. For atom numbering and assignment of NMR resonances see Figure S1 in Supporting Information.

(nBu4N)[cis-OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] (nBu4N[1])

To a solution of cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] (30 mg, 0.04 mmol) methanol (1 ml) under nitrogen NaBH4 (3 mg, 0.079 mmol) was added. After stirring for 1 h nBu4NCl (16 mg) in water (1 ml) was added. The orange solution produced a yellow-brown precipitate, which was filtered off, washed with cold water and diethyl ether and dried in vacuo to give a light-brown solid. Yield: 24 mg, 61%. Analytical data for nBu4N[1]: ESI-MS in MeOH (negative): m/z 567 [OsIIICl4(Hind)2]−, 332 [OsIIICl4]−. MIR, cm−1: 656, 752, 785, 833, 959, 1002, 1081, 1243, 1355, 1440, 1482, 1506, 1625, 2827, 2960 and 3285. 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500.26 MHz), δ: −22.16 (br. s, 2H), −7.06 (br. s, 2H), −0.63 (br. s, 2H), 0.32 (br. s, 2H), 1.12 (t, 12H, J = 7.5 Hz), 1.34 (br. s, 2H), 1.55 (sxt, 8H, J = 7.4 Hz), 1.96 (qui, 8H, J = 6.9 Hz), 2.33 (br. s, 2H), 3.55 (t, 8H, J = 7.8 Hz) ppm.

Na[cis-OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2]·H2O (Na[1]·H2O)

Compound nBu4N[1] (50 mg, 0.06 mmol) was dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of methanol and water (50 ml) under nitrogen atmosphere. Ion exchanger Dowex Marathon C, Na+-form was added to the solution after soaking for 12 h in water. After stirring of the suspension for 5 min the ion exchange resin was separated by filtration and the solution lyophilized to give a light-brown solid. Yield: 23 mg, 62%. Calcd for C14H12Cl4N4NaOs·H2O (Mr = 609.32), %: C, 27.60; H, 2.32; N, 9.20. Found, %: C, 28.08; H, 2.15; N, 8.72. ESI-MS in MeOH (negative): m/z 567.93 [OsIIICl4(Hind)2]−. MIR, cm−1: 652, 749, 834, 964, 1002, 1080, 1241, 1356, 1438, 1471, 1510, 1627, 2817 and 3313, 3510. 1H NMR (MeOH-d4, 500.26 MHz): δ −22.16 (br. s, 2H), −7.06 (br. s, 2H), −0.63 (br. s, 2H), 0.32 (br. s, 2H), 1.34 (br. s, 2H), 2.33 (br. s, 2H) ppm.

trans-[OsCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2]·2Me2SO ([2]·2Me2SO)

(H2ind)2[OsIVCl6] (166 mg, 0.25 mmol) was heated in the solid state at 150 °C in a glass oven for 45 h. The black product was extracted with methanol in a Soxhlet extractor for 24 h. The solvent was evaporated to give a blue product trans-[OsCl4(κN1-2H-ind)2] [3] contaminated with [2]. Very slow evaporation of a dimethyl sulfoxide solution of the raw product led to separation of few red crystals of [2]·2Me2SO.

Physical Measurements

UV–vis spectra were measured on a Jasco V-630 UV–vis spectrophotometer using samples dissolved in Me2CO, MeCN, DMF, Me2SO, EtOH, and THF. MIR spectra in the region 4000–600 cm−1 were recorded with a Thermo Nicolet NEXUS 470 FT-IR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), in KBr pellets. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was carried out with a Thermo Scientific LCQ Fleet ion trap instrument (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) by using methanol as a solvent. High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was carried out on a LTQ Orbitrap Velos instrument (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Expected and measured isotope distributions were compared. The cyclic voltammetric studies were performed in a homemade miniature electrochemical cell using a platinum wire as working and counter electrodes, and silver wire as pseudoreference electrode. Ferrocene served as the internal potential standard. The redox potentials in Me2SO solutions were recalculated vs Standard Hydrogen Electrode (NHE) using known redox potential of ferrocene (0.64 V) vs NHE. A Heka PG310USB (Lambrecht, Germany) potentiostat with a PotMaster 2.73 software package was used in cyclic voltammetric and spectroelectrochemical studies. In situ spectroelectrochemical measurements were performed on a spectrometer Avantes, Model AvaSpec-2048×14-USB2. Halogen and deuterium lamps were used as light sources (Avantes, Model AvaLight-DH-S-BAL) under an argon atmosphere in a spectroelectrochemical cell kit (AKSTCKIT3) with the Pt-microstructured honeycomb working electrode, purchased from Pine Research Instrumentation. The cell was positioned in the CUV-UV Cuvette Holder (Ocean Optics) connected to the diode-array UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer by optical fibers. UV–vis–NIR spectra were processed using the AvaSoft 7.7 software package. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 500 and 50 MHz on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz (Ultrashield Magnet) instrument by using as solvent MeOH-d4 and Me2SO-d6. The solvent residual peak for 1H and 13C was used as an internal reference. EPR spectra were recorded with the EMXplus X-band EPR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) equipped with the high-sensitivity resonator ER 4119 HS and the ER 4141 VT variable temperature unit as well as with a modified Bruker EMX spectrometer equipped with an Oxford Instruments cryostat for liquid helium temperature (10 – 20 K) X-band spectra and a modified Varian spectrometer for superfluid helium temperature (2 K) Q-band (~35 GHz) spectra. The EPR spectra were analyzed and simulated with the Easyspin toolbox.36 Ligand-field parameters for LS d5 systems were calculated using a fitting program originally provided by B. R. McGarvey33b and modified by J. Telser.32

Crystallographic Structure Determination

X-ray diffraction measurements of [1]·Me2CO and [2]·2Me2SO were performed on a Bruker X8 APEX-II CCD diffractometers at 199 and 100 K, respectively. The data were processed using SAINT software.37 The structures were solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least-squares techniques. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. H atoms were placed at calculated positions and refined as riding atoms in the subsequent least squares model refinements. The isotropic thermal parameters were estimated to be 1.2 times the values of the equivalent isotropic thermal parameters of the non-hydrogen atoms to which hydrogen atoms are bonded. The following computer programs and equipment were used: solution SHELXS-2014 and refinement, SHELXL-2014;38 molecular diagrams, ORTEP;39 computer, Pentium IV. Crystal data, data collection parameters, and structure refinement details are given in Table 1. CCDC1544885 and 1544886 contain the CIFs for this manuscript. All these data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Table 1.

Crystal data and details of data collection for [1]·Me2CO and [2]·2Me2SO.

| Compound | [1]·Me2CO | [2]·2Me2SO |

|---|---|---|

| empirical formula | C17H18Cl4N4OOs | C18H24Cl4N4O2OsS2 |

| Fw | 626.35 | 724.53 |

| space group | P21/c | P21/n |

| a [Å] | 13.1258(4) | 10.2354(6) |

| b [Å] | 12.2645(4) | 14.3781(6) |

| C [Å] | 17.8016(4) | 16.4733(9) |

| β [°] | 131.537(1) | 91.046(2) |

| V [Å3] | 2145.07(11) | 2423.9(2) |

| Z | 4 | 4 |

| λ [Å] | 1.54184 | 0.71073 |

| ρcalcd [g cm−3] | 1.939 | 1.985 |

| crystal size [mm] | 0.20 × 0.08 × 0.06 | 0.10 × 0.10 × 0.02 |

| T [K] | 199(2) | 100(2) |

| µ [mm−1] | 15.943 | 5.898 |

| R1[a] | 0.0180 | 0.0266 |

| wR2[b] | 0.0510 | 0.0579 |

| GOF[c] | 1.009 | 1.011 |

R1 = Σ║Fo| − |Fc║/Σ|Fo|.

wR2 = {Σ[w(Fo2 − Fc2)2]/Σ[w(Fo2)2]}1/2.

GOF = {Σ[w(Fo2 − Fc2)2]/(n − p)}1/2, where n is the number of reflections and p is the total number of parameters refined.

Computational Details

The Gaussian09 package40 has been used for the geometry optimizations of the anion 2[1]− (total charge minus one and doublet spin state). Unrestricted B3LYP41/def2-TZVP42 level of theory has been employed and the core electrons of osmium were treated via the SDD pseudo potential.43 Vibrational analysis showed that the optimized geometry of 2[1]− is free of imaginary (negative) frequencies.

The g-tensor values44 have been theoretically determined using two different approaches. The first attempt employed the ORCA software package45 at the DFT (with either BLYP or B3LYP functionals) and complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) levels of theory. Here the scalar ZORA Hamiltonian46 and uncontracted double zeta (UDZ) basis sets47 have been used together with inclusion of solvent effects via the conductor-like screening model (COSMO)48 of Me2SO. The spin-orbit coupling effects (SOC) have been included as a perturbation (with ORCA input settings: grid 7; soctype 3; socflags 1,3,3,1). The CASSCF calculation used five electrons in five orbitals and has been run as state specific (accounting formally for 10 roots). SOC treatment in CASSCF has been performed under default settings of the relativity module (dosoc true; g-tensor true). In the second approach, the ReSpect program package49 has been employed utilizing the four-component relativistic Dirac-Kohn-Sham (DKS) methodology.50, 51 In this way, the SOC effects are included variationally and thus account for higher than linear effects, which can be especially crucial in calculations of g-tensor values of compounds containing heavy elements such as osmium.52, 53, 54 The non-collinear Kramers unrestricted formalism was used as the best currently available method for description of spin polarization at the relativistic DFT level of theory.51, 54, 55 The recent implementation of solvent models in the ReSpect program51 allowed us to take into account effects of the environment (Me2SO) in the framework of COSMO model.

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

H446 small cell lung carcinoma (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) and HEK2-93 embryonic kidney cells (a kind gift from the laboratory of Dr. Ross Levine, MSKCC, New York, NY, USA) were maintained in Minimal Essential Medium. 4T1 breast carcinoma (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) cells were grown in RPMIM. HT-29 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (a kind gift from the laboratory of Dr. Vladimir Ponomarev, MSKCC, New York, NY, USA) were grown in McCoy’s medium. All media were supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and Penicillin (100 IU) and Streptomycin (100 µg/mL). All the cell lines were grown in 150 cm2 culture flasks (Corning Incorporated, New York, NY, USA) under standard sterile cell culture conditions at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air.

Cytotoxicity in Cancer Cell Lines

Cell viability was tested by the Alamar Blue assay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Stock solutions of the osmium compounds in Me2SO were prepared at a concentration of 30 mM. Cisplatin was dissolved in 0.9% aqueous solution of NaCl. Na[cis-OsIIICl4(Hind)2] (Na[1]) stock solution was prepared under an argon atmosphere to prevent direct contact with oxygen. Serial dilutions of the osmium compounds and cisplatin were prepared in the corresponding nutrient medium, ranging from 0.003 µM to 300 µM. All dilutions contained a final Me2SO concentration of 1%. For the Alamar Blue assay, cells were plated into 96-well plates (black, clear-bottom, Corning Incorporated) at a density of 4000 cells/well and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Then, the cells were incubated with osmium compounds or vehicle control (medium with Me2SO) for 48 h. The Alamar blue reagent was used as described by the manufacturer. The Alamar Blue reagent was diluted 1:10 in full culture medium to achieve the working solution. The medium was removed from 96-well plates and 100 µl Alamar Blue reagent was added. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h under protection from direct light. Fluorescence was read (bottom-read mode) using an excitation wavelength of 570 nm and an emission wavelength of 585 nm on a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The average reading values were analyzed by subtracting the background readings (wells with Alamar Blue but without cells) and compared against the untreated controls of each plate (defined as 100% viability) to determine the percentage of living cells. The experiment was carried out in six parallels of each compound.

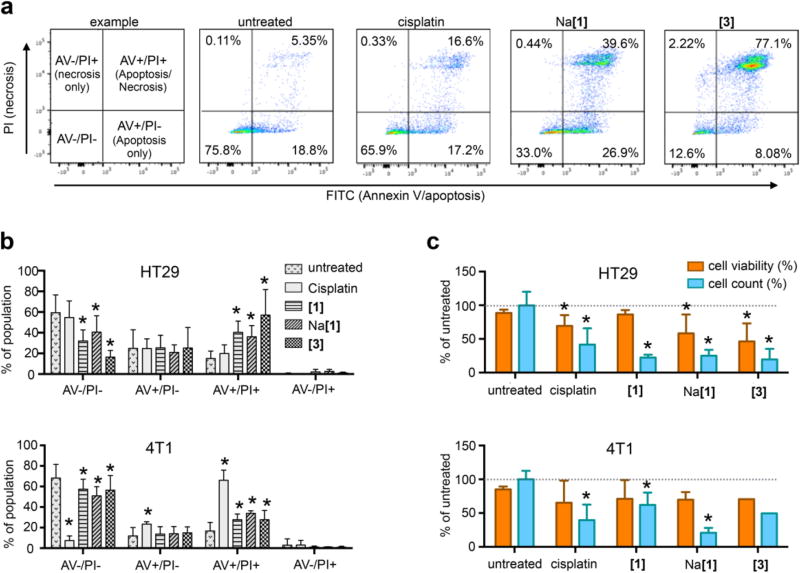

Measurement of antiproliferative activity and apoptosis induction

We evaluated the potential of complex [1] and Na[1] on cell viability, proliferation and apoptosis induction in comparison to trans-[OsIVCl4(κN1-2H-ind)2] ([3]),15 cisplatin and untreated cells using an Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (#640914; BioLegend). Thus, we plated 200,000 HT-29 or 4T1 cells per well in 6-well plates. After 24 h medium was removed and cells were incubated with fresh medium or a 200 µM solution of [1], complex Na[1], [3] or cisplatin in medium for 48 h. After trypsinization supernatant and cells were collected into Falcon tubes. 1 ml of the suspension was analyzed in an automated cell counter (Beckman Coulter Counter) for cell count and viability. The remaining cells were stained with a FITC Annexin V (AV) and Propidium Iodide (PI) Kit as described by the manufacturer. Cells were washed twice with cell staining buffer (#420201; BioLegend), resuspended in Annexin binding buffer and transferred to a flow tube with cell strainer cap (0.2−1×106 cells in 100 µl). Then, 5 µl Annexin V were added per sample, followed by 10 µl PI. The tubes were incubated for 15 min in the dark and then analyzed on a LSR Fortessa III Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Compensation was carried out using single stained controls. Cells that stained positive for Annexin V were considered early apoptotic, Annexin V and PI positive cells were considered late apoptotic or necrotic and cells positive only for PI were considered necrotic.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis

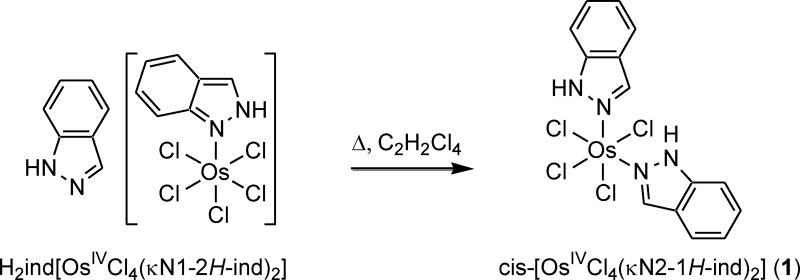

The complex cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([1]) was prepared by Anderson rearrangement56 in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane at 128 °C starting from (H2ind)[OsIVCl5(κN1-2H-ind)]. This transformation is unprecedented in this family of compounds as it implies both a change of coordination mode from κN1 to κN2 of one indazole ligand and substitution of chlorido ligand by outer sphere indazole. The second indazole binds via N2 to osmium(IV) with stabilization of the 1H-indazole tautomeric form (see Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 1 via Anderson rearrangement.

Starting from (H2ind)2[OsIVCl6] and by exploring the Anderson-rearrangement reaction, different types of osmium(IV) complexes, namely, two coordination isomers, (H2ind)[OsIVCl5(κN1-2H-ind)] and (H2ind)[OsIVCl5(κN2-1H-ind)], were synthesized. These complexes were studied for their antiproliferative activity in vitro and in vivo (Scheme 2).16, 57

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of two linkage isomers of osmium(IV) via Anderson rearrangement.

Solid state transformation of (H2ind)2[OsIVCl6] at 150 °C yielded trans-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([2]) as a side product and trans-[OsIVCl4(κN1-2H-ind)2] ([3])15 as the main species (Scheme 3). The minor product 2 could be identified by X-ray diffraction (vide infra).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of minor and major products 2 and 3 via Anderson rearrangements.

While trans-configured osmium analogues of KP1019 in oxidation states 3+ and 4+, namely [3]− and [3], have been reported in the literature,29, 15 the corresponding cis-compounds were not known. Complex [3] was further used for the synthesis of trans-[OsIIICl4(kN1-2H-ind)2]− ([3]−) by chemical or electrochemical reduction,29 building a link between the number of halido ligands, n, and Os formal oxidation state: trans-[OsIVCl4(Hazole)2] with n ≥ 4 and oxidation state 4+, and species with n < 4 and oxidation state 3+, as in mer-[OsIIICl3(Hazole)3],58 trans-[OsIIICl2(Hazole)4]Cl, and cis-[OsIIICl2(Hazole)4]Cl.35

This suggests an associative mechanism for the solid state reaction and a dissociative mechanism for the homogeneous reaction.59 The reduction of osmium(IV) to osmium(III) with NaBH4 was performed as described previously for [3]− 29 and [1]− was isolated as its tetra-n-butylammonium salt (nBu4N[1]). Cation metathesis employing an ion exchange resin60 afforded the sodium salt Na[1]. Compounds [1], nBu4N[1], and Na[1] were obtained in excellent to good yields of 93, 61, and 62%, respectively.

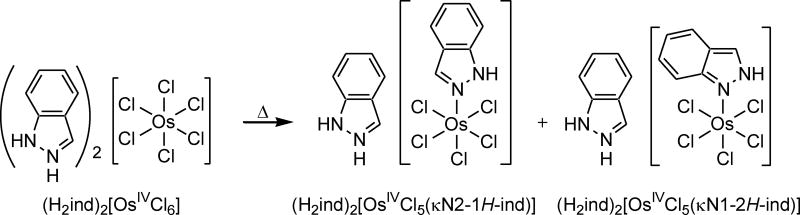

Crystal Structures

The results of X-ray diffraction studies of complexes [1]·Me2CO and [2]·2Me2SO are shown in Figure 1. Crystallographic data are summarized in Table 1, while selected bond lengths and angles are quoted in Table 2. To our knowledge these are the first tetrachlorido-bis(1H-indazole)osmium(IV) complexes to be crystallographically characterized. [1]·Me2CO and [2]·2Me2SO crystallized in the monoclinic centrosymmetric space groups P21/c and P21/n, respectively. The first contains one molecule of cis-[OsIVCl4(1H-ind)2] and one molecule of Me2CO, while the second contains one molecule of trans-[OsIVCl4(1H-ind)2] and two of Me2SO in the asymmetric unit. The osmium atom in [1] displays a distorted octahedral coordination geometry with two chlorido ligands and two 1H-indazole ligands in equatorial positions, and two chlorido ligands bound axially. In [2] the osmium(IV) adopts a compressed octahedral coordination geometry with four chlorido ligands occupying the equatorial plane and two 1H-indazole ligands in the axial positions. In a few cases reported in the literature, 1H-indazole was found to be deprotonated, acting as a bridging ligand in polynuclear metal complexes,61 or even more rarely it operates as a monodentate indazolato ligand, such as when coordinated via N2 to platinum and deprotonated at N1 in the square planar complex [PtCl(N-indazolato)(PPh3)2].62

Figure 1.

ORTEP views of [1] and [2] Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level.

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) in the coordination polyhedron of osmium(IV) in [1], [2] and [3].

| Atom1–Atom2 | [1]·Me2CO | [2]·2Me2SO | [3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Os–N1 | 2.050(5) | ||

| Os–N2 | 2.077(2) | 2.063(3) | |

| Os–N11 | 2.082(2) | 2.055(3) | |

| Os–Cl1 | 2.3158(6) | 2.3022(8) | 2.3439(16) |

| Os–Cl2 | 2.3174(6) | 2.3222(9) | 2.3395(15) |

| Os–Cl3 | 2.2974(7) | 2.3099(8) | |

| Os–Cl4 | 2.3251(6) | 2.3197(9) | |

| N1–N2 | 1.358(3) | 1.357(4) | |

| Atom1–Atom2–Atom3 | |||

| N1–Os–Cl1 | 91.73(15) | ||

| N1–Os–Cl2 | 89.32(15 | ||

| N2–Os–N11 | 90.51(8) | 177.52(10) | |

| N2–Os–Cl2 | 89.54(6) | 89.99(8) | |

| Cl1–Os–Cl2 | 90.85(2) | 89.82(3) | 90.22(6) |

| Cl1–Os–N11 | 89.09(6) | 91.78(8) | |

| Cl1–Os–Cl4 | 90.30(2) | 90.36(3) | |

| N11–Os–Cl4 | 87.42(6) | 90.87(8) | |

| N2–Os–Cl4 | 89.01(6) | 90.23(8) | |

| Cl2–Os–Cl4 | 91.91(2) | 179.72(3) |

Comparison of the bond lengths in the coordination sphere of osmium in [1], [2], and [3] is shown in Table 2. Inspection of geometric parameters in complexes [1] and [2] with the same coordination mode of indazole shows that the Os–N2 and Os–N11 bonds are significantly longer (0.02 Ǻ; 5.5 × σ) in the cis- than in the trans-isomer (see Figure 1 and Table 2). The same trend is obvious when the Os–N bonds in cis-complex [1] are compared to those in trans-isomer [3] with a dissimilar coordination mode of indazole (see Chart 2). This is presumably due to a stronger trans-influence of the chloride ligand compared to nitrogen atom N2 or N1 (using the numbering for indazole in Chart 1) of indazole. Interestingly, an insignificant (< 3 × σ) shortening of axial Os–N bonds in trans-complex [3] compared to that in trans-complex [2] (coordination modes are different) results in a significant (14 × σ) lengthening of equatorial Os–Cl bonds by ca. 0.03 Å (see Table 2) in [3] vs those in [2].

Both trans-indazole ligands in [2] are almost coplanar in contrast to what was found in (Ph4P)[trans-RuCl4(1H-indazole)2], wherein the 1H-indazole ligands were significantly twisted.63 The plane through both azole ligands crosses the equatorial plane between chlorido ligands, the torsion angles ΘCl1–Os–N1–N2, ΘCl2–Os–N2–N1 being −30.4(4) and −47.8(2)°, respectively.

A salient structural feature is the stabilization of indazole in its usual 1H-indazole form in [1] and [2] (Figure 1) and coordination to osmium via nitrogen atom N2. This mode of coordination is typical for other metal ions, e.g. ruthenium, but rare for osmium(IV). The only previous example for osmium, namely H2ind[OsIVCl5(1H-ind)], was reported by some of us recently.57

Intermolecular hydrogen bonding interaction between complexes [1] and [2] and co-crystallized solvent molecules are shown in Figures S2 and S3 in Supporting Information.

NMR Spectra

All compounds were characterized by 1H NMR spectra showing signals due to coordinated indazole. In the spectrum of nBu4N[1], signals of the Bu4N+ cation could also be assigned. The paramagnetic osmium(IV) in [1] caused some line broadening and spread of chemical shifts from −9.42 to +16.49 ppm (Figure S4). It should, however, be noted that despite the paramagnetism of osmium(IV) in [1], the NMR lines remain sharp enough so that coupling constants could be easily determined. Qualitatively, the fact that the nuclear paramagnetic resonance spectrum of [1] is readily interpretable is unsurprising for OsIV (low-spin (LS) 5d4, S = 1) because this ion is expected to have very fast electron spin relaxation64 due to the substantial orbital angular momentum of its ground state and the extremely large spin-orbit coupling (SOC) constant of OsIV (free-ion Os4+(g) (Os V in spectroscopic notation) has ζd = 4133.7 cm−1);65 ions with slow electronic relaxation, such as high-spin (HS) 3d5 S = 5/2 (e.g., FeIII), in contrast, typically give unusable NMR spectra.64 The number of carbon resonances in 13C NMR spectra of [1] is in agreement with C2 molecular symmetry of the complex. The broadening of resonances due to paramagnetism of the osmium(III) (low-spin 5d5 S = 1/2) in nBu4N[1] and Na[1] is more obvious compared to that for [1] and signal splitting for indazole protons is no more discernible. All signals are significantly upfield shifted being in the δ range from 3.55 to −22.16 ppm.

UV–vis spectra and solvatochromism

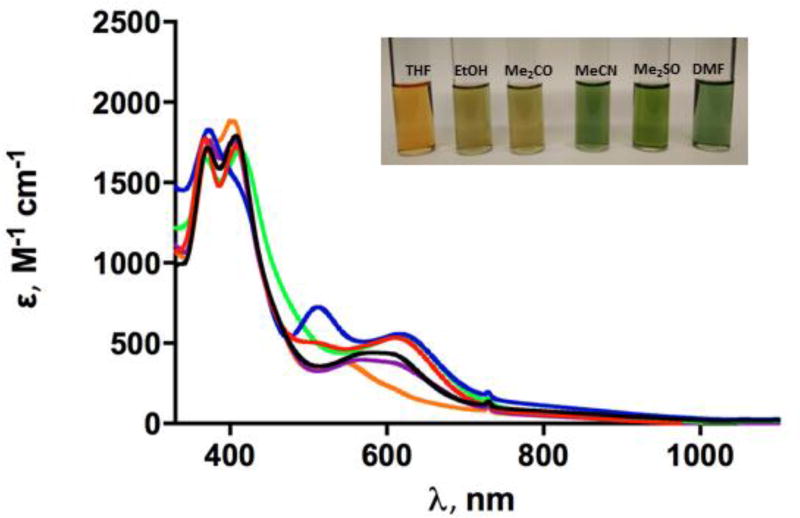

The UV–vis spectra of [1] have been measured in a number of organic solvents (Figure 2). In dependence of the solvent used a red shift of the absorption maximum from 559 to 618 nm was observed. This is in line with the relative permittivity values (εr) of solvents used [tetrahydrofuran (7.5),66 acetone (21.30),67 ethanol (25.02),67 acetonitrile (38),68 dimethyl formamide (37.31),69 dimethyl sulfoxide (47.2)].70 This can be explained by the better stabilization of (polar) excited states by likewise polar solvents.

Figure 2.

UV–vis spectra of solutions of [1] in Me2CO (black), acetonitrile (red), DMF (blue), Me2SO (green), ethanol (purple) and THF (orange).

Electrochemical Behavior

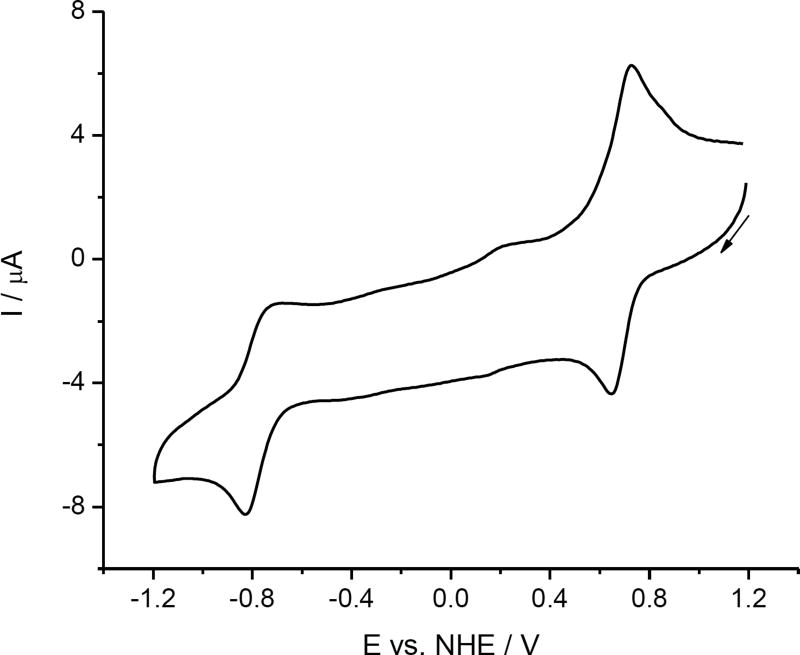

The cyclic voltammogram of [1] in a solution of 0.2 M nBu4NPF6 in acetonitrile starting from the anodic part using a platinum wire working electrode and a scan rate of 0.2 V s−1 is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Cyclic voltammogram of cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([1]) in 0.2 M nBu4NPF6 in acetonitrile at platinum working electrode (scan rate 0.2 V s−1).

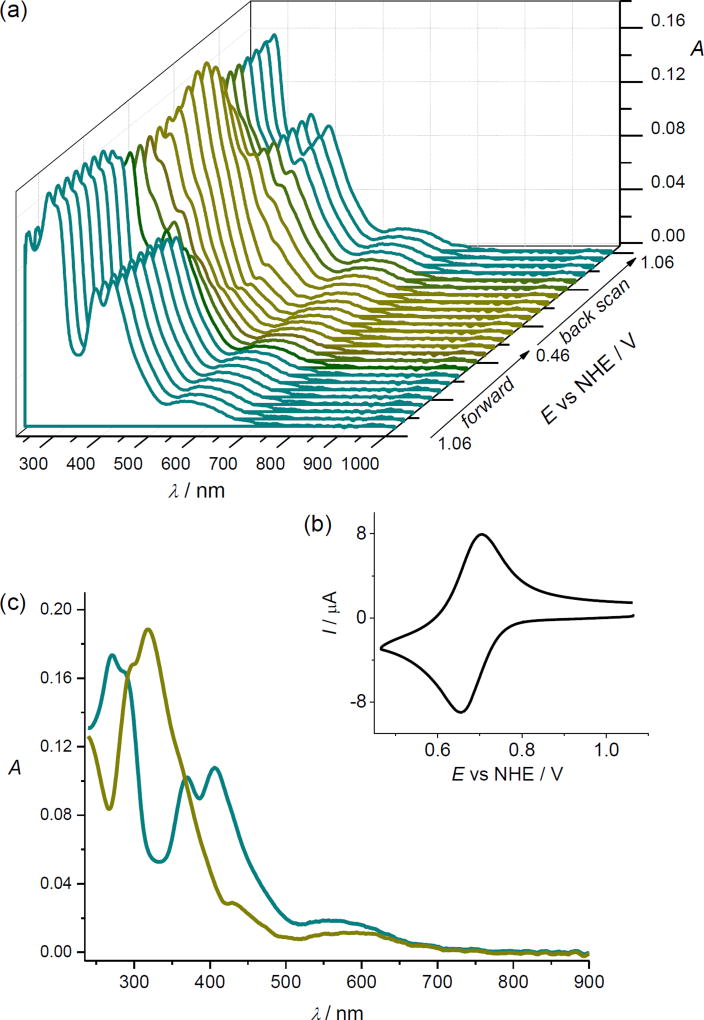

The first reduction step is reversible (E1/2 = 0.69 V vs NHE or +0.01 V vs Fc+/Fc) at all scan rates used (from 10 mV s−1 to 500 mV s−1), and is followed by the less reversible one at a more negative potential (E1/2 = −0.78 V vs NHE). Upon the in situ reduction at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 in the region of the first reversible cathodic peak in acetonitrile, the UV–vis absorption bands at 408, 370 and 272 nm decreased, and, simultaneously, a new dominating band at 318 nm appeared (Figure 4a). Fully reversible spectroelectrochemical behavior confirmed the high stability of cathodically generated cis-[OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2]− ([1]−) species. Very similar reversible cyclic voltammetric and spectroelectrochemical response was observed for [1] also in Me2SO at the first reduction peak even at a very low scan rate of 5 mV s−1 as illustrated in Figure S5. Here the UV–vis absorption bands of [1] in Me2SO at 415, 370 and 280 nm decreased, and simultaneously, a new dominating band at 325 nm was observed. The spectroelectrochemical data indicated that isolation of the osmium(III) species in the solid state after reduction of parent osmium(IV) complex is feasible. The chemically prepared and isolated osmium(III) complex nBu4N[1] can be easily oxidized in Me2SO back to [1]0 at anodic potential E = +1.0 V vs NHE as shown in Figure S6.

Figure 4.

UV–vis spectroelectrochemistry of [1]. (a) Electrochemical potential dependence of optical spectra. (b) The corresponding cyclic voltammogram (0.2 M nBu4NPF6 in acetonitrile, scan rate 10 mV s−1). (c) Optical spectrum of [1] in 0.1 M nBu4NPF6/acetonitrile before (dark cyan trace) and after cathodic reduction at the first reduction peak (dark yellow trace – UV–vis spectrum measured at 0.46 V vs NHE).

Figure 4c shows the absorption spectra of the initial cis-isomer [1] (cyan trace) and one-electron reduced species, namely ([1]−) (dark yellow trace). The UV−vis spectrum of the osmium(III) species [1]− generated electrochemically exhibits an absorption maximum at slightly higher wavelength (318 nm in acetonitrile and 325 nm in Me2SO) compared to its analogue trans-[OsIIICl4(κN1-2H-ind)2]− ([3] in Me2SO) reported previously29 with λmax at 301 nm. Of note is a more negative reduction potential with a shift of −200 mV reported recently for [3]29 with E1/2 = +0.49 V vs NHE or E1/2 = −0.19 V vs Fc+/Fc for the first reduction step. A significant difference in the E1/2 values for [1] and [3] indicates a stronger effect of cis/trans isomerism on reduction potentials than that of the coordination mode of indazole in the compared species.

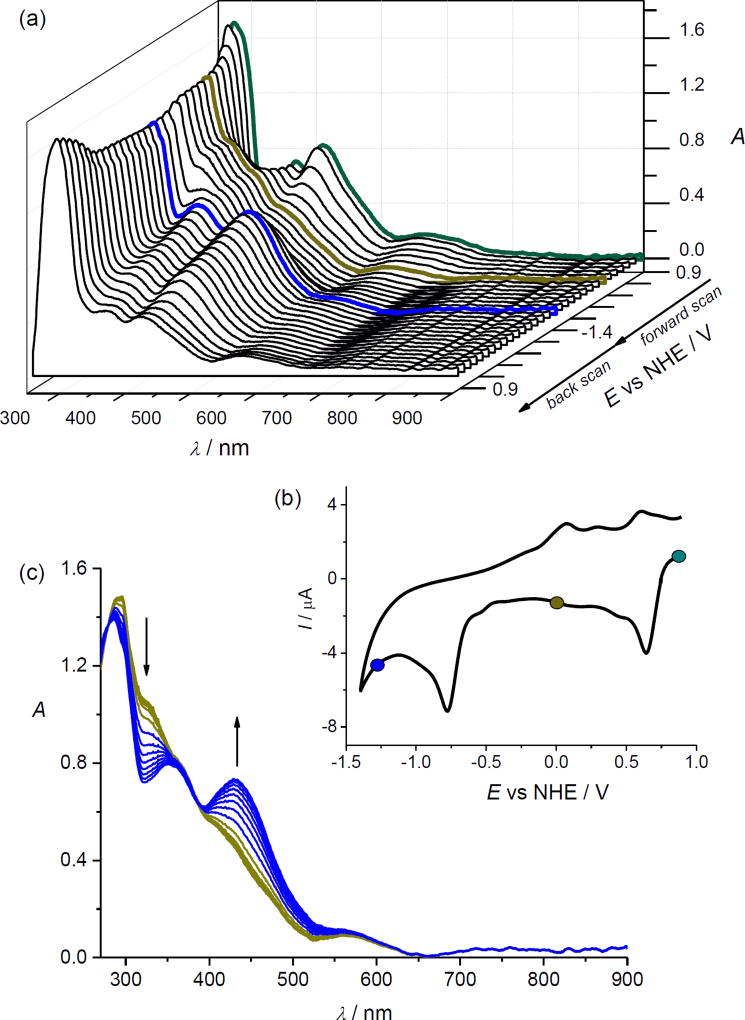

As mentioned previously, the OsIII/II couple is much less reversible than the OsIV/III couple and takes place at much more negative potentials. Upon repetitive redox cycling of sample 1 going up to the voltage of the second reduction peak, irreversible changes were observed in cyclic voltammetric experiments in the thin layer cell at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 both for Me2SO and acetonitrile solutions as illustrated in Figure S7. New redox active species are formed during the reduction of [1]− in the region of the second electron transfer indicating lower stability of the generated osmium(II) complex. The changes in UV–vis spectra observed during cyclic voltammetry of [1]− going to the region of the second reduction in Me2SO solution (scan rate 5 mV s−1) are shown in Figure 5. A new optical band arises at ca. 440 nm in the region of the second electron transfer (see Figure 5c and Figures S8 and S9) which again disappears upon the reoxidation. Irreversible changes of the initial optical spectra of [1] were observed confirming irreversible chemical changes of the corresponding osmium(II) species [1]2− formed upon cathodic reduction of [1] at the second reduction step. Interestingly, the newly formed product can be reversibly reduced at E1/2 = +0.27 V vs NHE (see blue trace in Figure S7). Cathodically induced metal dechlorination was previously mentioned for trans-[RuIIICl4(Hind)2]− complex71 upon reduction of ruthenium(III) to ruthenium(II) and for the trans-OsIII analogues.29 Similarly, our findings indicate that a chlorido ligand is replaced by a solvent molecule upon reduction of osmium(III) species and a new redox active osmium(II) complex containing a coordinated solvent molecule is formed at the second reduction potential of [1]0 (respectively at the first reduction peak for [1]−).

Figure 5.

In situ UV–vis spectroelectrochemistry for [1] in 0.2 M nBuN4[PF6] in Me2SO (scan rate 5 mV s−1): (a) UV–vis spectra observed upon cyclic voltammetry of [1] going to the second reduction peak. (b) The corresponding in situ cyclic voltammogram (selected colored UV–vis spectra in (a) correspond to the potentials marked with the colored circles in the voltammogram); (c) UV–vis spectra detected simultaneously upon the reduction of [1] in the region of the second cathodic peak (from −0.5 to −1.3 V vs NHE).

EPR of osmium(III) complexes

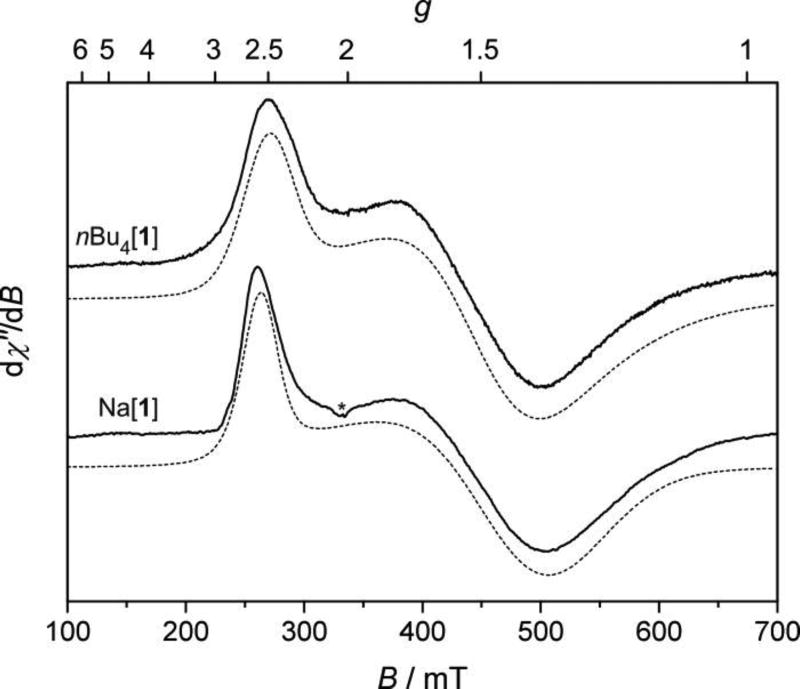

As mentioned previously, the NMR resonances of the osmium(III) complexes nBu4N[1] and Na[1] were considerably broadened due to the rapid nuclear relaxation induced by the paramagnetism of these compounds, which could be expected from the LS d5 electron configuration of the central metal.33b, 33c EPR is a valuable technique to unravel the underlying mechanisms of action of paramagnetic anticancer drugs and, in particular, those of ruthenium(III).31 The X-band EPR spectra of frozen solutions of nBu4N[1] (in Me2SO at 94 K) and Na[1] (in H2O/ethylene glycol 5:1 v.v. at 12 K) are shown in Figure 6 and confirm the paramagnetic nature of the complexes, while a Q-Band EPR spectrum of Na[1] and a powder EPR spectrum of nBu4N[1] are in Figs. S10 and S11, respectively.

Figure 6.

(top) X-band (9.436 GHz) EPR spectrum of nBu4N[1] in Me2SO recorded at 94 K (solid trace) together with the simulation (dashed trace). (bottom) X-band (9.362 GHz) EPR spectrum of Na[1] in H2O/ethylene glycol 5:1 v/v recorded at 12 K (solid line) together with the simulation (dashed line). Spin Hamiltonian parameters are listed in Table 3. * denotes the signal from an impurity.

Both spectra show rather broad lines with ΔBpp > 150 mT and not very well resolved spectral pattern, characterized by a rhombic g-tensor.72 The g values obtained by the simulation of the spectra (Table 3, gmax ≈ 2.50, gmid ≈ 1.45, gmin ≈ 1.35) are very similar and can be considered virtually identical for both complexes, if we take into account the uncertainty of g-value determination induced by the large linewidth. Thus the cis-[OsIIICl4(κN2-1H-ind)2]− complex anion geometry in frozen solution, as well as the electronic configuration, are not influenced by the different counterions that govern the solubility of nBu4N[1] and Na[1] in organic or aqueous environment, respectively. An unambiguous conclusion about the spin state of a complex cannot be made based solely on a single frequency cw-EPR experiment.73 However, the interactions between the unpaired electrons in the high spin states usually result in a facilitated electron spin relaxation, and the consequent line broadening renders their EPR spectra often undetectable above liquid helium temperatures. The fact that we were able to record the spectrum of nBu4N[1] at 94 K and a comparable linewidth was observed in the spectrum of Na[1] at 12 K, indicate the absence of such electron-electron interactions. The osmium(III) ion is thus in the usual low spin d5 (S = ½) configuration, in both nBu4N[1] and Na[1], as reported for the vast majority of OsIII complexes in the literature.33a, 33b

Table 3.

The g-values of OsIII complexes nBu4N[1], Na[1] obtained from simulation of their EPR spectra

| g-factor a | nBu4N[1] b | Na[1] c |

|---|---|---|

| gmax | 2.44 ± 0.05 | 2.50 ± 0.05 |

| gmid | 1.44 ± 0.05 | 1.45 ± 0.05 |

| gmin | 1.31 ± 0.05 | 1.37 ± 0.05 |

While EPR is unable to provide the absolute sign of the g factor the ligand field theory analysis indicates that the g values are all negative for the investigated complexes (see Table 4). The assignment of g-tensor component directions is not made here; only ordering by magnitude (see Table 4 for such assignments).

In Me2SO at 94 K

In H2O/ethylene glycol 5:1 v/v at 12 K.

Ligand field theory discussion of 2[1]− g-tensor

The g values of LS nd5 complexes have been extensively analyzed over the years because of the importance of this electronic configuration in heme proteins and other bioinorganic systems.74 The model that we shall use for a simple ligand-field theory (LFT) analysis of the g tensor of 2[1]− is that developed by McGarvey.33b, 33c The details need not be discussed here, but the model treats this t2g5eg0 configuration (strong-field notation) by ignoring any effects of excited states involving the eg orbitals and using the “hole” in the t2g orbitals as a basis set as follows:75

The (axial) splitting between the dxy and dxz,yz orbitals is given by Δ and the (rhombic) splitting between the dxz and dyz orbitals is given by V. This analysis has been used previously for RuIII complexes of general type trans-[RuIII(NH3)4(L)(L′)]n+,76 which could be considered as cationic analogues to the equatorially tetrachlorido coordinated anionic Ru/OsIII complexes. To our knowledge, no EPR spectra of complexes of general formula cis-[OsIIIX4(L)(L′)] have been reported. Clarke and co-workers have reported EPR spectra for cis-[RuIII(NH3)4(Him)2]Br3.77 It is possible to use analytical equations given by McGarvey to extract an internally consistent set of LFT parameters from the experimental g values.78 This has been done here and the results are given in Table 4. In each case, there are two solutions, but usually, one can be discarded as it requires unreasonable parameters, e.g., the orbital reduction factor, k, is much too far from 1.0, or the splittings among the t2g orbitals is much too large. Note that in this model it is not possible to provide the absolute energy splittings among the t2g orbitals, only their energies normalized by the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) constant, ζ. This parameter has recently been accurately determined for free-ion Os3+(g) (Os IV in spectroscopic notation) in its 5d5 electronic configuration: ζd = 3738.6 cm−1.79 The reduction of this parameter due to covalency in these complexes is unknown, but values of ζ = 2530, 2220 cm−1 in trans-[OsCl4(CO)(py)]− (py = pyridine) are found respectively for Cs+ and tetraethylammonium countercation.34 That the SOC constant is so sensitive even to counterion indicates the difficulty in quantifying this interaction, but an estimate of ζ ≈ 2500 cm−1 seems reasonable in our case (reduction by roughly one third of the free-ion value), so can be used to convert the calculated Δ/ζ and V/ζ values into estimates as to ligand-field splittings. It should also be noted that all of the trans-[OsX4(L)(L′)]− (X = Cl, Br, I; L = CO, L′ = CO, py) complexes studied by Kremer gave axial EPR spectra. This is a consequence of the linear (cylindrical π-bonding) binding of CO ligand to osmium. Axial EPR spectra are also seen for complexes of type trans-[RuCl4(L)(Me2SO)]−, where L = Me2SO80 or various azole ligands, e.g., pyrazole, as well as pyridine.81 The key point, however, is not that whether a (Ru,Os)III species exhibits a rhombic or axial spectrum, but whether g║ (i.e., the unique feature) is greater (at lower resonant magnetic field) or less (at higher field) than g⊥ (averaging a rhombic signal if necessary). In general, the (Ru,Os)III species listed in Table 4 exhibit |g║| < |g⊥|, but [1]− has the reversed g value ordering.

Table 4.

The g-values of RuIII and OsIII complexes relevant to the present work with results from LFT analysis.

| Complex a | gx, gy, gzi | Δ/ζh | V /ζh | V / Δ | k |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nBu4N[1] | −1.31, −1.44, −2.44 | −0.492 | −0.043 | 0.088 | 0.8204 |

| Na[1] | −1.37, −1.45, −2.50 | −0.498 | −0.026 | 0.053 | 0.8541 |

| trans-[OsCl4(CO)(py)]−b | −2.55, −2.55, −1.72 | +0.228 | 0.0 | 0 | 1.220 |

| trans-[OsBr4(CO)(py)]−b | −2.50, −2.50, −1.80 | +0.236 | 0.0 | 0 | 1.211 |

| trans-[OsBr4(CO)2]−b | −2.46, −2.46, −1.81 | +0.221 | 0.0 | 0 | 1.192 |

| trans-[RuCl4(Him)2]−c | −3.12, −2.44, −1.2 | +0.536 | +0.316 | 0.589 | 1.256 |

| trans-[RuCl4(Me2SO)2]−d | −2.35, −2.35, −1.87 | +0.166 | 0.0 | 0 | 1.148 |

| trans-[Ru(NH3)4(Him)2]3+e | −3.04, −2.20, (−0.15); | +0.9635; | +0.6043; | 0.627; | 1.002; |

| −3.04, −2.20, (+0.15); | +1.136; | +0.7123; | 0.627; | 0.9667; | |

| (−0.9), −2.20, −3.04; | −0.6392; | −0.4016; | 0.628; | 1.114; | |

| (+0.9), −2.20, −3.04 | −1.847 | −1.160 | 0.628 | 0.9270 | |

| cis-[Ru(NH3)4(Him)2]3+e | −2.88, −2.14, (−0.65); | +0.6905; | +0.4265; | 0.618; | 1.003; |

| −2.88, −2.14, (+0.65); | +1.463; | +0.9017; | 0.616; | 0.8360; | |

| −2.88, −2.14, (−0.15); | +0.9253; | +0.5357; | 0.579; | 0.9255; | |

| −2.88, −2.14, (+0.15) | +1.094 | +0.6328 | 0.579 | 0.8858 | |

| [Os(NH3)5(H2O)]3+f | −2.3, −2.3, −1.22; | +0.3855; | 0.0; | 0.0; | 0.9795; |

| −2.2, −2.2, −1.08 | +0.4097 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8954 | |

| [Ru(NH3)5(H2O)]3+g | −2.620, −2.620, −0.6; | +0.7119; | 0.0; | 0.0; | 1.052; |

| −2.620, −2.620, (0.0) | +0.9878 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9678 | |

| trans-[Ru(NH3)4(4-pic)(H2O)]3+h | −1.20, −1.56, −2.81 | −0.671 | −0.112 | 0.167 | 0.9378 |

Counterions are not given except for the two OsIII complexes reported here, but are noted for others below when relevant.

Taken from Kremer;34 py = pyridine. The g values presented are all for complexes with tetraethylammonium countercation; for trans-Cs[OsCl4(CO)(py)]: g⊥ = 2.46, g║ = 1.45.

Taken from Ni Dhubhghaill et al.82

Taken from de Paula et al.80 The g values reported are for the solid material; in aqueous or methanol solution, multiple species are reported due to replacement of Me2SO and/or chlorido ligands by solvent.

Taken from Clarke et al.77 The values for |gmin| were not observed (hence they are given in parentheses), but were proposed by their LFT analysis. In these systems, the proper choice of sign of the g values is not apparent based on standard criteria, namely the magnitudes of k or Δ, so both choices are given. Results of additional calculations are given; for the trans complex, using a value for |gmin| that would likely be the largest possible, but difficult to observe experimentally: |gmin| = 0.9; for the cis complex using the a value for |gmin| that would likely be the smallest possible: |gmin| = 0.15 (a value of zero is possible, but does not provide enough information for the fitting process). We favor the first entry listed in each case, which is in agreement with the model originally favored by Clarke et al.

Taken from McGarvey et al.33c Two species are always observed in frozen aqueous solutions of [Os(NH3)5(H2O)](CF3SO3)3.

Taken from McGarvey et al.33c The experimentally reported range for |gmin| is 0.0 ≤ |gmin| ≤ 0.6; we thus present calculations for both 0.6 and 0.0 – the minimum magnitude.

Taken from Souza et al.;32 4-pic = 4-picoline (4-methylpyridine). The specific g values reported are those for frozen aqueous/ethylene glycol solution; those for a powder and in other solvents were similar.

The signs of the g values are not determined experimentally, but are determined here by the model of McGarvey,33b which provides two choices of sign. Only the more physically plausible choice of signs is presented, except when both choices are acceptable.

McGarvey has explained the electronic structure of trans-[MX4(Y2,YZ)] complexes (where M = RuIII most commonly) in terms of an angular overlap model (AOM) wherein the z axis is along Y-M-Y(Z) and the relevant AOM parameter is π-bonding between the metal ion and each ligand type, ɛπ(X, Y, Z), so that Δ = 2επ(X)–[{2επ(Y)},{επ(Y)+επ(Z)}]. McGarvey showed that this model works reasonably well for simple complexes such as trans-[RuCl2(NH3)4]+. More relevant here, the model also works qualitatively for trans-[OsBr4(CO)2]−: the bromido ligands are expected to be π-donors (i.e., ɛπ (X) > 0) and the carbonyl ligands strong π-acceptors (i.e., ɛπ (Y)< 0). This would give Δ > 0, consistent with what obtains from the g value analysis. No cis-[MX4(Y2,YZ)] complexes were known to McGarvey, but he proposed that Δ = –επ (X) + ε π (Y) for this geometry.33b The chlorido ligands (X) are expected to be π-donors and the indazole nitrogen atoms (Y) weak π-acceptors επ (Y) ≲0, which would give Δ < 0, again consistent with the g values.

A further discussion of the LFT parameters of these complexes is beyond the scope of this study, and would be in any case risky due to the overall relatively small number of OsIII coordination complexes characterized by EPR. However, it is clear that the cis-OsIII complex, [1]−, as manifest in its “reversed” EPR spectrum, exhibits an electronic structure distinctly different from almost all of the related species listed in Table 4, in particular the trans-OsIII complexes. The wavefunction coefficients resulting from this analysis show that the “hole” is primarily in the dxz, dyz orbitals in the present system, while it is primarily in the dxy orbital in most other cases. The exception is [Ru(NH3)4(4-pic)(H2O)]3+ (4-pic = 4-picoline (4-methylpyridine)) wherein competing π-bonding involving the trans ligands was proposed to lead to the change in electronic ground state.32 A quantum chemical theory (QCT) treatment presented in the next section provides further insight into [1]−.

Theoretical determination of 2[1]− g-tensor

QCT calculations of EPR parameters of compounds containing heavy elements are challenging due to a dominating importance of spin-orbit relativistic effects. While in the case of compounds containing 3d transition metal complexes it is sufficient to treat the relativistic SOC effects in the evaluation of the g-tensor as a perturbation of the non-relativistic wavefunction,44 in the case of 4d- and 5d- transition metal compounds the explicit inclusion of both scalar and SOC relativistic effects82 appears neccessary.51, 52, 53, 54, 55 Herein, we wish to compare the performance of the g-tensor evaluation of 2[1]− using a perturbative inclusion of SOC in the scalar relativistic ZORA wavefunction using either DFT or CASSCF levels of theory44 with the rigorous treatment of relativistic effects and g-tensor evaluation at the DKS level.51, 52, 53, 54, 55 Furthermore, the solvent polarization effects will be considered for further consistency via the COSMO approach.

The calculated g-tensor values are shifted from the experimental ones in the case of scalar ZORA DFT calculations with the perturbative inclusion of SOC. The solvent effects are large within the ZORA DFT treatment but do not lead to improvement with respect to experiment. Considerably better agreement is achieved in the case of ZORA CASSCF calculations which yield a semi quantitative agreement with experiment [both in vacuo and via the COSMO(Me2SO) solvent model]. Nevertheless, the CASSCF setup has been kept under conservative settings for the rotations out of the active space to enforce the d-electronic configuration of the open shell and/or in the active space. Although the rigorous DKS method does not yield the best agreement in vacuo, introducing a solvent model leads to large improvement of the calculated results providing almost quantitative agreement with the experiment. This once again shows the need for a proper treatment of both relativistic and spin polarization effects in calculation of EPR parameters for 5d ions. As such, the calculated solvent effects on the electronic g-tensor parameters are so far the largest ones observed at the DKS level of theory and to the best of our knowledge, they are the largest calculated for systems containing heavy elements. Furthermore, the excellent agreement of DKS/COSMO theory with experimentally determined values are promising for a more systematic theoretical exploration of experimentally determined g-tensors for osmium(III) compounds,34 and potentially other paramagnetic 5d5 ion complexes, such as of rhenium(II)83 or iridium(IV).84

Effective concentrations to affect cell viability

Having now the availability of well-characterized cis- as well as trans-osmium(III) complexes it is possible to make a direct comparison of their anti-cancer efficacy. Specifically, first to determine in which concentration range these complexes mediate cytotoxic effects, we conducted a cytotoxicity screen in four different cancer cell lines (HT29, 4T1, HEK293, H446) and compared the effects to an untreated control and cisplatin. The results for select drug concentrations are displayed in Figure 7. Strong effects on cell viability were only observed for the highest concentration of 300 µM, where all cell lines showed a viability of below 30% compared to the control, with the exception of 4T1 cells to treatment with trans-[OsIVCl4(kN1-2H-ind)2] ([3]). At 30 µM cisplatin reduced cell viability to 30–60%, while the osmium compounds did not reduce viability. HT29 cells were the only cells were the osmium compounds led to a stronger reduction of cell viability than cisplatin. The corresponding IC50 values are quoted in Table S1.

Figure 7.

Cell viability of human cancer cell lines after a 48 h treatment with cisplatin, [1], Na[1] and [3], in relation to the untreated control (1% Me2SO) using the AlamarBlue assay kit. Displayed are means ± standard deviation of six parallels.

Antiproliferative activity in cancer cell lines

We further determined the potential of complexes [1] and Na[1] to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in comparison to trans-[OsIVCl4(κN1-2H-ind)2] ([3]) and cisplatin in HT29 and 4T1 cells at a concentration of 200 µM. Here, we used an apoptosis detection kit to quantify the percentage of a cell population that has entered an early apoptotic (AV+/PI-) or late apoptotic/necrotic state (AV+/PI+) using flow cytometry (Figure 8a). We found that the 4T1 (breast cancer) cells were very sensitive to cisplatin (more than 60% increase in AV+ and AV+/PI+ cells compared to untreated cells), while HT29 (colorectal) cells showed no significant difference between untreated and cisplatin treated cells (Figure 8b). Interestingly, the cisplatin resistant HT29 cells were more sensitive to treatment with the osmium complexes than 4T1 cells. Especially, the AV+/PI+ population increased significantly to 40.3 % ([1]), 36.0% (Na[1]) and 57.2% ([3]) upon treatment (vs 15.1% untreated, p<0.05), indicating the trans-isomer induced apoptosis most effectively in HT29 cells (Figure 8b).

Figure 8.

Antiproliferative effects of treatment with 200 µM cisplatin, [1], Na[1] or [3], on HT29 and 4T1 cancer cell lines. (a) Example of discriminability of apoptotic and necrotic cell populations in HT29 cells after a 48 h treatment using a flow cytometry assay. (b) Quantification of early apoptotic and late apoptotic/necrotic cell populations in treated and untreated cells. (c) Relative cell viability and cell number after a 48 h treatment with the respective compound compared to untreated cells. * p<0.05 (unpaired Student’s t-test, always compared to untreated control). Displayed are the mean ± standard deviation values of at least six samples pooled from at least two biological replicates.

In the cisplatin sensitive 4T1 cells, we also observed a significant increase in the AV+/PI+ population for all osmium compounds, but it was less pronounced ([1]: 27.7%, Na[1]: 33.9%, trans-[OsIVCl4(kN1-2H-ind)2]: 27.6%, untreated: 16.8%) and the cis- and trans-isomers [1] and [3] showed no difference (Figure 8b).

In addition to flow cytometry data, we also measured cell viability and cell number of each sample in an automated cell counter. We found more pronounced effects on cell count than on cell viability, indicating that proliferation was affected, but cells remained viable (Figure 8c). In HT29 cells, cell viability was significantly affected by cisplatin, Na[1] and [3]. The cell number was strongly reduced by over 75% by all osmium compounds and to 41% by cisplatin (Figure 8c). In 4T1 cells, the strongest effect on cell count was observed for the cis-compound Na[1] (20.9% of untreated), followed by cisplatin 39.5% (Figure 8c).

Conclusion

In this work we reported on the synthesis and crystal structure of cis-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([1]), the first cis-configured isomer in the series of compounds of the general formula [OsIVCl4(Hazole)2], where Hazole = indazole, pyrazole, benzimidazole, and imidazole. In addition, we showed that trans-[OsIVCl4(κN2-1H-ind)2] ([2]) is also available, although more effective synthetic routes still need to be developed. Both compounds are complementary to their elsewhere reported trans-isomer [OsIVCl4(κN1-2H-ind)2] ([3]). Electrochemical and chemical one-electron reduction of [1] afforded cis-configured osmium(III) species isolated as tetrabutylammonium and sodium salts, nBu4N[1] and Na[1], respectively. X-band EPR spectra of nBu4N[1] in Me2SO at 94 K and Na[1] in H2O/ethylene glycol 5:1 v/v at 12 K are characterized by ill-resolved broad lines with a rhombic g-tensor indicating the low-spin 5d5 (S = ½) electronic configuration of osmium(III) in these complexes. A simple ligand-field theory analysis of the g values indicates that in these cis-isomers, the electronic configuration differs from that of trans-analogs in that the electron “hole” is primarily in a dxz,yz orbital as opposed to a dxy orbital in the much more commonly found species with trans-geometry. The g-tensor of the OsIII complexes of interest was further probed by quantum chemical theory. Specifically, the g-tensor values calculated by DKS/COSMO theory (with involvement of the solvent model) are in quite good agreement with those determined experimentally. Access to both cis- and trans-isomers of osmium(IV) and osmium(III) that are water soluble prompted us to investigate their in vitro anti-cancer activities. The complexes [1], Na[1] and [3] showed antiproliferative effects on cancer cells which were not coupled to their sensitivity to cisplatin. Cytostatic effects were stronger than actual cell killing at 48 h incubation time. HT29 cells showed a higher sensitivity to treatment with osmium complexes than cisplatin. 4T1 cells showed lower rates of apoptosis induction by the osmium complexes than cisplatin, but a very strong cytostatic effect was observed for the cis-isomer Na[1]. The unavailability of larger scale procedure for the synthesis of the trans-isomer [2] makes the direct disclosure of the effect of geometrical isomerism on cytotoxicity in this case not possible. From the other side, a direct extrapolation of the results of the antiproliferative activity and cytostatic effects of the cis-isomer Na[1] on the ruthenium analogues is not possible as well, if one takes into account the body of accumulated evidence and cytotoxicity data for related ruthenium and osmium compounds28, 29, 35, 57, 60, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 and complexity of the problem.91 Even though the analogous cis-isomers of KP1019/NKP1339 remain unknown, their synthesis appears to be imminent, giving an opportunity that deserves to be exploited in the search for more effective metal-based anticancer drugs than those currently in clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Table 5.

Results summary of the theoretical determination by quantum chemical theory calculations of the g-tensor compared with experimental data.

| Method | gx | gy | gz | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXP. (94 K) | 1.31 | 1.44 | 2.44 | Me2SO |

| EXP. (12 K) | 1.37 | 1.45 | 2.50 | H2O/ethylene glycol 5:1 v/v |

|

| ||||

| ZORA/BLYP | 2.056 | 3.649 | 5.087 | in vacuo |

| 2.030 | 4.731 | 5.507 | COSMO(Me2SO) | |

|

| ||||

| ZORA/B3LYP | 2.041 | 4.428 | 5.094 | in vacuo |

| 2.021 | 4.908 | 7.258 | COSMO(Me2SO) | |

|

| ||||

| ZORA/CASSCF | 1.665 | 1.780 | 3.090 | in vacuo |

| 1.594 | 1.702 | 3.188 | COSMO(Me2SO) | |

|

| ||||

| DKS/B3LYP | 0.729 | 2.002 | 2.536 | in vacuo |

| 1.262 | 1.797 | 2.471 | COSMO(Me2SO) | |

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexander Roller for collecting X-ray diffraction data for compound 4·2Me2SO. The financial support of the Slovak Grant Agency VEGA (Contract Nos. 1/0598/16 and 1/0416/17) and the Slovak Research and Development Agency (Contract Nos. APVV-15-0053, APVV-15-0079 and APVV-15-0726) are duly acknowledged. The work has also received financial support from the SASPRO Program (Contract no. 1563/03/02), co-financed by the European Union and the Slovak Academy of Sciences. The computational resources for this project have been provided by the NOTUR high-performance computing program [grant number NN4654K] and by the HPC center at STU (SIVVP Project, ITMS code 26230120002). We thank Prof. Brian M. Hoffman, Northwestern University, for use of the low temperature X- and Q-band EPR spectrometers, which is supported by the United States NIH (GM 111097 to B.M.H.). The authors thank the support of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Flow Cytometry Core Facility. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NIH R01CA204441 (T.R.), R21CA191679 (T.R.) and P30 CA008748. The authors thank the Tow Foundation and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Center for Molecular Imaging & Nanotechnology (S.K.). Financial support by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology is also greatfully acknowledged (G.B., J.E.).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Atom numbering scheme for NMR resonances assignment (Figure S1), details of crystal structures of [1]·Me2CO and [2]·2Me2SO (Figures S2 and S3), 1H NMR spectrum of [1] (Figure S4), details of UV–vis–NIR spectroelectrochemistry and UV–vis spectra for [1] and nBu4N[1] in Me2SO and acetonitrile (Figures S5–S9), Q-band EPR spectrum of Na[1] in aqueous solution (Figure S10), powder X-band EPR spectrum of nBu4N[1] (Figure S11), results of Alamar Blue assay (Table S1).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

DEDICATION

Dedicated to Professor Dr. Karl Wieghardt on the occasion of his 75th birthday anniversary.

References

- 1.Mathews CJ, Barnett SP, Smith SC, Barnes NJ, Whittingham WG, Williams J, Clarke ED, Whittle AJ, Hughes DJ, Armstrong S, Viner R, Macleod Fraser TE, Crowley PJ, Salmon R, Pilkington BL. Pesticidal indazole or benzotriazole derivatives. Internat. Patent WO. 2000:A1. 063207. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hood J, Wallace DM, Kumar S. Indazole inhibitors of the wnt signal pathway and therapeutic uses thereof. Internat. Patent WO. 2011:A1. 019651. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerecetto H, Gerpe A, González M, Arán VJ, Ochoa de Ocáriz C. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2005;5:869–878. doi: 10.2174/138955705774329564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elguero J, Alkorta I, Claramunt RM, Lopez C, Sanz D, Santa Maria D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:8027–8031. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Yang Q, Romero JAC, Cross J, Wang B, Poutsiaka KM, Epie F, Bevan D, Wu Y, Moy T, Daniel A, Chamberlain B, Carter N, Shotwell J, Arya A, Kumar V, Silverman J, Nguyen K, Metcalf CA, Ryan D, Lippa B, Dolle RE. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:1080–1085. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandanayaka V, Singh J, Zhao L, Gurney ME. N-linked aryl heteroaryl inhibitors of Ita4h for treating inflammation. Patent US. 2007:A1. 0142434. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Down K, Amour A, Baldwin IR, Cooper AWJ, Deakin AM, Felton LM, Guntrip SB, Hardy C, Harrison ZA, Jones KL, Jones P, Keeling SE, Le J, Livia S, Lucas F, Lunniss CJ, Parr NJ, Robinson E, Rowland P, Smith S, Thomas DA, Vitulli G, Washio Y, Hamblin JN. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:7381–7399. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw D, Wang SM, Villasenor AG, Tsing S, Walter D, Browner MF, Barnett J, Kuglstatter A. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;383:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiemann K, Mallinger A, Wienke D, Esdar C, Poeschke O, Busch M, Rohdich F, Eccles SA, Scheider R, Raynaud FI, Czodrowski P, Musil D, Schwarz D, Urbahns K, Blagg J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:1443–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burris HA, Bakewell S, Bendell JC, Infante J, Jones SF, Spigel DR, Weiss GJ, Ramanathan RK, Ogden A, von Hoff D. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000154. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) interzyne.com/it-139/.

- 11.Schmidt A, Beutler A, Snovydovych BB. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008:4073–4095. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stadlbauer WW. Sci. Synth. 2002;12:227–324. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haddadin MJ, Conrad WE, Kurth MJ. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2012;12:1293–1300. doi: 10.2174/138955712802762059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhn P-S, Meier SM, Jovanović KK, Sandler I, Freitag L, Novitchi G, González L, Radulović S, Arion VB. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016:1566–1576. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Büchel GE, Stepanenko IN, Hejl M, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK, Arion VB. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:7690–7697. doi: 10.1021/ic200728b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Büchel GE, Stepanenko IN, Hejl M, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK, Heffeter P, Berger W, Arion VB. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;113:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg B, Van Camp L, Krigas T. Nature. 1965;205:698–699. doi: 10.1038/205698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleare MJ, Höschele JD. Platimum Met. Rev. 1973;17:2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleare MJ, Höschele JD. Bioinorg. Chem. 1973;2:187–210. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Farrell N, Ha TTB, Souchard JP, Wimmer FL, Cros S, Johnson NP. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:2240–2241. doi: 10.1021/jm00130a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Montero EI, Diaz S, Gonzalez-Vadillo AM, Perez JM, Alonso C, Navarro-Ranninger C. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:4264–4268. doi: 10.1021/jm991015e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) van Zutphen S, Pantoja E, Soriano R, Soro C, Tooke DM, Spek AL, Den Dulk H, Brouwer J, Reedijk J. Dalton Trans. 2006:1020–1023. doi: 10.1039/b512357g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Grabner S, Modec B, Bukovec N, Bucovec P, Čemažar M, Kranjc S, Serša G, Sčančar J. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016;161:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2016.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Kelland LR, Barnard CFJ, Evans IG, Murrer BA, Theobald BRC, Wyer SB, Goddard PM, Jones M, Valenti M, Bryant A, Rogers PM, Harrap KR. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:3016–3024. doi: 10.1021/jm00016a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Coluccia M, Nassi A, Boccarelli A, Giordano D, Cardellicchio N, Locker D, Leng M, Sivo M, Intini FP, Natile G. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;77:31–35. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Werner A. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1908;40:4817–4825. [Google Scholar]; (b) Werner A. Z. Anorg. Chem. 1897;14:28–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Arion VB, Reisner E, Fremuth M, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK, Kukushkin VY, Pombeiro AJL. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:6024–6031. doi: 10.1021/ic034605i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keppler BK, Lipponer K-G, Stenzel B, Kratz F. New tumor-inhibiting ruthenium complexes. In: Keppler BK, editor. Metal Complexes in Cancer Chemotherapy. VCH; 1993. pp. 187–220. [Google Scholar]; (c) Stepanenko IN, Cebrian-Losantos B, Arion VB, Krokhin AA, Nazarov AA, Keppler BK. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2007:400–411. doi: 10.1021/ic700405y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni WX, Man WL, Yiu SM, Ho M, Cheung MTW, Ko CC, Che CM, Lam YW, Lau TC. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:1582–1588. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basri AM, Lord RM, Allison SJ, Rodriguez-Barzano A, Lucas SJ, Janeway FD, Shepherd HJ, Pask CM, Phillips RM, McGowan PC. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:6341–6356. doi: 10.1002/chem.201605960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolf S, Preetz WZ. Anorg. Allgem. Chem. 1999;625:411–416. [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Doadrio A, Craciunescu D, Ghirvu C, Nuno JC. An. Quim. 1977;73:1220–1223. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lai S-W, Chan QK-W, Zhu N, Che C-M. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:11003–11016. doi: 10.1021/ic070290l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kostova I, Soni RK. Int. J. Curr. Chem. 2010;1:133–143. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ni W-X, Man W-L, Cheung MT-W, Sun RW-Y, Shu Y-L, Lam Y-W, Che C-M, Lau T-C. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:2140–2142. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04515b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tang Q, Ni W-X, Leung C-F, Man W-L, Lau KK-K, Liang Y, Lam Y-W, Wong W-Y, Peng S-M, Liu G-J, Lau T-C. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:9980–9982. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42250j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Man W-L, Lam WWY, Lau T-C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:427–439. doi: 10.1021/ar400147y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Suntharalingam K, Lin W, Johnstone TC, Bruno PM, Zheng Y-R, Hemann MT, Lippard SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14413–14416. doi: 10.1021/ja508808v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Omar SAE, Scattergood PA, McKenzie LK, Bryant HE, Weinstein JA, Elliott PIP. Molecules. 2016;21:1382. doi: 10.3390/molecules21101382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Zhu J, Dominijianni A, Rodríguez-Corrales JÁ, Prussin R, Zhao Z, Li T, Robertson JL, Brewer KJ. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2017;454:155–161. [Google Scholar]; (k) Yang C, Wang W, Li G-D, Zhong H-J, Dong Z-Z, Wong C-Y, Kwong DWJ, Ma D-L, Leung C-H. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42860. doi: 10.1038/srep42860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stepanenko IN, Büchel GE, Keppler BK, Arion VB. Osmium complexes with azole heterocycles as potential antitumor drugs. In: Kretsinger RH, Uvetsky VN, Permyakov VN, editors. Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins. Springer; New York: 2013. pp. 1596–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhn P-S, Büchel GE, Jovanović KK, Filipović L, Radulović S, Rapta P, Arion VB. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:11130–11139. doi: 10.1021/ic501710k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verdejo B, Acosta-Rueda L, Clares PM, Aguinaco A, Basallote MG, Soriano C, Tejero R, García-España E. Inorg. Chem. 2015;54:1983–1991. doi: 10.1021/ic5029004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prosser KE, Walsby CJ. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017:1573–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Souza ML, Castellano EE, Telser J, Franco DW. Inorg. Chem. 2015;54:2067–2080. doi: 10.1021/ic5030857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Rieger PH. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1994;135/136:203–286. [Google Scholar]; (b) McGarvey BR. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998;170:75–92. [Google Scholar]; (c) McGarvey BR, Batista NC, Bezerra CWB, Schultz MS, Franco DW. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:2865–2872. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kremer S. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1984;85:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stepanenko IN, Krokhin AA, John RO, Roller A, Arion VB, Jakupec MA, Keppler BK. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:7338–7347. doi: 10.1021/ic8006958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoll S, Schweiger A. J. Magn. Reson. 2006;178:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.SAINT-Plus (Version 7.06a) and APEX2. Madison, Wisconsin; USA: 2004. Bruker-Nonius AXS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burnett MN, Johnson GK. ORTEPIII. Report ORNL-6895. OAK Ridge National Laboratory; Oak Ridge, TN: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Nakatsuji H, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasegawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian 09, revision D.01. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Becke AD. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. [Google Scholar]; (c) Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF, Frisch MJ, J M. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11623–11627. [Google Scholar]; (d) Vosko SH, Wilk L, Nusair M. Can. J. Phys. 1980;58:1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) Schaefer A, Horn H, Ahlrichs R. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;97:2571–2577. [Google Scholar]; (b) Weigend F, Ahlrichs R. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:3297–3305. doi: 10.1039/b508541a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andrae D, Häuβermann U, Dolg M, Stoll H, Preuβ HH. Theor. Chim. Acta. 1990;77:123–141. [Google Scholar]

- 44.(a) Neese F, Solomon EI. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:6568–6582. doi: 10.1021/ic980948i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Neese F. J. Chem. Phys. 2001;115:11080–11096. [Google Scholar]; (c) Neese F. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2003;380:721–728. [Google Scholar]; (d) Neese F. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;122:034107. doi: 10.1063/1.1829047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Neese F. Mol. Phys. (honorary issue for Prof. Peter Pulay) 2007;105:2507–2514. [Google Scholar]; (f) Sandhoefer B, Neese F. J. Chem. Phys. 2012;137:094102. doi: 10.1063/1.4747454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Ganyushin D, Neese F. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138:104113. doi: 10.1063/1.4793736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Mader-Cosper M, Neese F, Astashkin AV, Carducci MA, Raitsimring AM, Enemark JH. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:1290–1301. doi: 10.1021/ic0483850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neese F. The ORCA program system, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 46.(a) van Lenthe E, Baerends EJ, Snijders JG. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;99:4597–4610. [Google Scholar]; (b) van Wüllen C. J. Chem. Phys. 1998;109:392–399. [Google Scholar]

- 47.(a) Jorge FE, Canal Neto A, Camiletti GG, Machado SF. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:064108. doi: 10.1063/1.3072360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Canal Neto A, Jorge FE. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013;582:158–162. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sinnecker S, Rajendran A, Klamt A, Diedenhofen M, Neese F. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006;110:2235–2245. doi: 10.1021/jp056016z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komorovsky S, Repisky M, Malkin VG, Malkina OL, Kaupp M, Ruud K, with contributions from. Bast R, Ekström U, Kadek M, Knecht S, Konecny L, Malkin E, Malkin-Ondik I, Di Remigio R. ReSpect, version 3.5.0 2016 – Relativistic Spectroscopy DFT program of authors. doi: 10.1063/5.0005094. http://www.respectprogram.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Repisky M, Komorovsky S, Malkin E, Malkina OL, Malkin VG. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010;488:94–97. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Remigio RDi, Repisky M, Komorovsky S, Hrobarik P, Frediani L, Ruud K. Mol. Phys. 2017;115:214–227. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malkin I, Malkina OL, Malkin VG, Kaupp M. J. Chem. Phys. 2005;123:244103. doi: 10.1063/1.2135290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hrobarik P, Repisky M, Komorovsky S, Hrobarikova V, Kaupp M. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2011;129:715–725. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gohr S, Hrobarik P, Repisky M, Komorovsky S, Ruud K, Kaupp M. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2015;119:12892–12905. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b10996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cherry PJ, Komorovsky S, Malkin VG, Malkina OL. Mol. Phys. 2016;115:75–89. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davies JA, Hockensmith CM, Kukushkin VYu, Kukushkin YuN. Synthetic Coordination Chemistry – Principles and Practice. World Scientific; Singapore: 1995. pp. 392–396. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Büchel GE, Stepanenko IN, Hejl M, Jakupec MA, Arion VB, Keppler BK. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:10737–10747. doi: 10.1021/ic901671j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiorescu I, Stepanenko IN, Arion VB, Krokhin AA, Keppler BK. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007;12(Suppl. 1):226. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gavriluta A, Büchel EG, Freitag L, Novitchi G, Tommasino JB, Jeanneau E, Kuhn P-S, González L, Arion VB, Luneau D. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:6260–6272. doi: 10.1021/ic4004824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Büchel GE, Gavriluta A, Novak M, Meier SM, Jakupec MA, Cuzan O, Turta C, Tommasino J-B, Jeanneau E, Novitchi G, Luneau D, Arion VB. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:6273–6285. doi: 10.1021/ic400555k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.(a) Rendle DF, Storr A, Trotter J. Can. J. Chem. 1975;53:2930–2943. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cortes-Llamas SA, Hernández-Pérez JM, Hô M, Muñoz-Hernández M-A. Organometallics. 2006;25:588–595. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fackler JP, Jr, Staples RJ, Raptis RG. Z. Kristallogr. 1997;212:157–158. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peti W, Pieper T, Sommer M, Keppler BK, Giester G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1999:1551–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravero E. NMR of Paramagnetic Molecules, Volume 2, Second Edition: Applications to Metallobiomolecules and Models (Current Methods in Inorganic Chemistry) 2 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Azarov VI, Raassen AJJ, Joshi YN, Uylings PHM, Ryabtsev AN. Phys. Scr. 1997;56:325–343. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Roy P, Jana AK, Das D, Nath DN. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009;474:297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mohsen-Nia M, Amiri H, Jazi B. J. Solution Chem. 2010;39:701–708. [Google Scholar]