Abstract

Self-medication theory (SMT) posits that individuals exposed to trauma and resulting posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSD) are at risk for heavy drinking and associated negative consequences. Close peer alcohol use is also a powerful predictor of alcohol involvement in college, particularly influencing those with greater negative affect. As individuals with PTSD may rely on peers for support, peer drinking behaviors are possibly putting them at further risk for greater alcohol use and resulting consequences. In order to test self-medication processes, the present study examined the relationship between weekday PTSD symptoms, weekend alcohol behavior, and the influence of both emotionally supportive peer and other friend drinking behavior by investigating: (1) whether weekday PTSD symptoms predicted subsequent weekend alcohol use and consequences; and (2) whether the relationship between weekday PTSD symptoms and weekend alcohol behavior was moderated by various drinking behaviors of one’s peers. Trauma-exposed heavy-drinking college students (N=128) completed a baseline assessment and 30 daily, web-based assessments of alcohol use and related consequences, PTSD symptoms, and peer alcohol behavior. Results directly testing SMT were not supported. However, friend alcohol behavior moderated the relationship between weekday PTSD and weekend alcohol behavior. Findings highlight the importance of peer drinking as both a buffer and risk factor for problematic drinking and provide useful information for interventions aimed at high-risk drinkers.

Keywords: Weekend drinking, college, alcohol, PTSD, social support

Disorder Symptoms and Alcohol Use in College Students Heavy alcohol use during college is both common (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011) and problematic (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). Trauma exposure also is common in college, with rates ranging between 66–84% (Read, Ouimette, White, Colder, & Farrow, 2011; Smyth, Hockemeyer, Heron, Wonderlich, & Pennebaker, 2008). Such exposure is linked to the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Read et al., 2011). College students with PTSD face numerous deleterious academic, behavioral, and health outcomes (Bachrach & Read, 2012; Flood et al., 2009; Rutter, Weatherill, Krill, Orazem, & Taft, 2013); perhaps most notable among these are higher rates of problem drinking (Avant, Davis, & Cranston, 2011; McDevitt-Murphy, Weathers, Flood, Eakin, & Benson, 2007). Self-medication theory (SMT) has been forwarded to explain the co-occurrence of PTSD and hazardous alcohol behavior. SMT posits that individuals with PTSD may use substances through a negative reinforcement process to reduce distressing symptomatology (Khantzian, 2003). Though empirical support for SMT is somewhat mixed (e.g., Breslau, Davis, & Schultz, 2003; Miller, Vogt, Mozley, Kaloupek, & Keane, 2006), PTSD symptoms have been shown to predict problematic drinking in some studies (e.g., Hruska & Delahanty, 2012; Read et al., 2012).

SMT may best be tested by considering PTSD-alcohol associations dynamically in order to capture how these associations change as symptoms vary (Read, Bachrach, Wright, & Colder, 2016). Experience sampling methodologies (ESM) have been especially helpful in this respect, with some such studies showing that alcohol behavior may increase in response to within-day or previous-day increases in PTSD symptoms (e.g., Gaher et al., 2014; Kaysen et al., 2014; Simpson, Stappenbeck, Varra, Moore, & Kaysen, 2012). However, not all studies using ESM have shown this association (Cohn, Hagman, Moore, Mitchell, & Ehlke, 2014) and questions remain as to why or for whom this link is strongest. The application of ESM to shed light on PTSD and drinking outcomes may be especially useful for understanding how these associations may play out against the unique backdrop of the college environment – where drinking is ubiquitous and normative (Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006). A particularly unique feature of the college environment is that drinking tends to occur most frequently and at greatest quantities during weekends, most likely due to academic demands (Del Boca, Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004; Hoeppner et al., 2012; Tremblay et al., 2010). Thus, SMT processes in college may follow this pattern, whereby those with greater PTSD symptoms may be able to cope during the week but be more vulnerable during the weekend when peers tend to drink in harmful quantities (Read et al., 2012). As such, this routinized pattern also points to an important feature of alcohol use in college – the highly social context in which this drinking occurs. Because peers are central to the drinking context of young adults (Borsari & Carey, 2006), they may play a critical role in PTSD-alcohol associations – a role that has not yet been examined.

Peer Influence During College

In early adulthood, peers emerge as the primary source of social influence (Arnett, 2005). Accordingly, it is not surprising that college drinking is powerfully motivated by social factors (e.g., Bachrach, Merrill, Bytschkow, & Read, 2012; Borsari & Carey, 2006; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Larimer, 2007). Specifically, the drinking behaviors of one’s immediate peer group can put individuals at risk for harmful alcohol use and consequences. These influences are multi-faceted, including directly such as encouragement to drink (“active” influences such as drink offers; Read, Wood, & Capone, 2005; Wood, Read, Palfai, & Stevenson, 2001), as well as indirectly (“passive” influences), such as normative perceptions about the drinking attitudes and behaviors of others (Borsari & Carey, 2003; Reifman, Watson, & McCourt, 2006). Additionally, peer influences are stronger in relationships that are emotionally closer (Talbott, Moore, & Usdan, 2012) and thus the drinking of those who serve as emotional supports may be an especially powerful influence on drinking. Lastly, research has underscored the importance of modeling both active and passive peer influences separately as both facets show unique associations with alcohol use and related problems in college (Borsari & Carey, 2001; Neighbors et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2008; Read et al., 2005). Active and passive peer drinking may have important implications for students with greater PTSD symptoms, as intervention implications may differ depending on the type of influence.

In addition, the literature overwhelmingly highlights the significance of emotionally supportive peers for those with trauma and PTSD, as these peers can help facilitate positive post-trauma adaptation (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003; Pietrzak et al., 2010). Emotional support can be conceptualized as having peers who are emotionally encouraging, available during stress, trusting, and empathic, and who provide comfort (Tracy & Whittaker, 1990). Because peers strongly influence drinking in college, the overlap between one’s emotionally supportive peer group and the drinking behaviors of that group may be especially important to assess in those with PTSD. To date, no studies have examined how peer alcohol use might modify drinking behaviors in individuals with PTSD. However, the larger literature on the relationship between negative affect and alcohol use has found that both lower friendship quality (Hussong, Hicks, Levy, & Curran, 2001) and greater peer substance use (Hussong & Hicks, 2003) strengthens the relationship between negative affect and drinking in adolescents and emerging adults. These results highlight the complicated pathway towards harmful alcohol use, as self-medication processes may be stronger for individuals whose peers engage in substance use (e.g., Hussong, Jones, Stein, Baucom, & Boeding, 2011). It is possible that those with greater PTSD symptoms may drink and experience more alcohol-related consequences if exposed to more peer drinking influences.

However, peer influence can be time-varying, as the amount and type of contact with peers differs from day to day. Recent findings from O’Grady, Cullum, Tennen, and Armeli (2011) highlight the dynamic nature of peer influences, finding that students drink more on days when others around them drink more. Yet, most peer influence research has been cross-sectional (e.g., Buckner, Ecker, & Proctor, 2011; Lau-Barraco and Collins, 2011; Neighbors et al., 2008) and thus has not captured these processes dynamically. Changes in social influence may help in understanding PTSD-alcohol associations; when symptom severity increases, students may drink in response, and this relationship might be stronger for those who drink with peers or whose peers offer them a drink. Therefore, inclusion of peer drinking as a moderator of the PTSD-alcohol relationship is important in understanding this co-occurrence in the context of college.

ESM Approaches to Studying PTSD and Alcohol

Recent research assessing either alcohol use (e.g., Armeli, Conner, Cullum, & Tennen, 2010) or PTSD (Kaysen et al., 2014; Naragon-Gainey, Simpson, Moore, Varra, & Kaysen, 2012) has successfully employed ESM in college populations, demonstrating substantial within-person variability. To date, only a handful of studies have assessed the link between PTSD and alcohol behavior using ESM (Cohn et al., 2014; Gaher et al., 2014; Kaysen et al., 2014; Possemato et al., 2015; Simpson et al., 2012; Simpson, Stappenbeck, Luterek, Lehavot, & Kaysen, 2014), and only one of these used a college sample (Kaysen et al., 2014). Findings suggest that for some, PTSD symptom severity is associated with greater same-day alcohol craving, alcohol use, and/or next-day alcohol use, providing support for SMT (e.g., Kaysen et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2014). However, for others, a direct link between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use has not been supported (Cohn et al., 2014). Moreover, none of these studies assessed the impact of emotionally supportive peer drinking on one’s own drinking nor looked at how PTSD symptoms over the course of the week may predict alcohol behavior on the weekends. Testing for moderators, such as peer alcohol behavior, can perhaps shed light on the extant mixed findings, as peers could confer risk for problematic alcohol use for those with PTSD. In addition, studies that capture how psychopathology and peers promote risky drinking within the unique context of college can be crucial for improving interventions focused on reducing harmful alcohol use.

The Current Study

The goal of the present study was to test self-medication processes between PTSD symptoms and alcohol behavior in the context of the college social environment. We sought to examine: (1) whether weekday PTSD symptoms predicted subsequent weekend alcohol behavior; and (2) whether peer drinking moderated these associations. To do this, we followed trauma-exposed, heavy-drinking college students daily over a period of 30 consecutive days, assessing PTSD symptoms, alcohol use, alcohol-related consequences, and participants’ emotionally supportive peer group and other friends/acquaintances’ alcohol behavior (i.e., whether one drank with a peer, peer alcohol quantity, drink offers, and approval of alcohol use). In addition, models were run separately to predict weekend alcohol use and weekend alcohol-related consequences, as PTSD and other expressions of negative affect have shown unique and differing etiological associations with these two types of drinking outcomes (Carey & Correia, 1997; Gaher, et al., 2014; Read et al., 2013). Moreover, brief motivational interventions address not just drinking quantity and frequency, but consequences experienced. Thus, it will be important to clarify whether PTSD symptoms uniquely predict subsequent drinking and/or consequences in order to effectively modify interventions. We hypothesized the following: (1) When weekday PTSD symptoms increase in severity, students will drink heavier and experience more alcohol-related consequences during the subsequent weekend; (2) This relationship will be stronger for those drinking with supportive peers, for those drinking with supportive peers who consume more, for those whose supportive peers believe it is highly acceptable to drink, and/or for those whose supportive peers offer them a drink. We hypothesized that supportive peer drinking would act as a risk factor, based on a large body of research showing that close peer drinking behavior affects one’s own use more so than more distal social influences (e.g., the drinking attitudes of the university in general, drinking behavior of someone of one’s own gender; see Borsari & Carey, 2001). As participants might not always drink with their emotionally supportive peers, we also assessed and separately modeled the drinking behaviors of “other friends/acquaintances.” Parallel hypotheses regarding the moderating role of these friends/acquaintances’ drinking behavior were forwarded.

Method

Participants

College students were recruited from the Introductory to Psychology research pool of a mid-sized northeastern university over the course of one year (across Fall and Spring semesters). Students participated in a “pre-screening” session to facilitate recruitment of the targeted sample (see Supplementary Material). Eligible students were between the ages of 18–24, heavy drinkers (binge drank once/month during the previous three months), and reported at least one DSM-IV Criterion A trauma (as assessed by Criteria A1 (objective experience of a trauma) and A2 (subjective feelings of fear, helplessness, or horror); American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Two-hundred and twenty-seven students were eligible and recruited via email, which described the opportunity to participate in a research project on daily behaviors (see Procedures). Out of this 227, 132 (58.1%) students were interested in participating and completed a baseline web-survey and were subsequently invited to continue with the daily portion of the study. Four participants either did not complete any daily diaries or completed fewer than three days and were removed from future analyses, leaving a final sample of 128.

The present sample

The final sample (N = 128) was 50% female with a Mage of 18.84 (SD = 1.14). Race/ethnicity was as follows: 76.6% Caucasian, 8.6% Multiracial, 8.6% Asian American, 5.5% Black or African American, and .8% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. In addition, approximately 8.6% of the sample considered themselves Hispanic or Latino. The majority of the sample was college freshmen (52.3%) or sophomore (30.5%), lived in a residence hall on campus (67.2%) and was not affiliated with the Greek system (72.7%).

Procedures

Recruitment and Consent

Students interested in participating followed a personalized link to a baseline web-survey, which included an IRB-approved informed consent reviewing study procedures in greater detail. After providing consent, participants completed the baseline survey, which assessed alcohol behavior, trauma history, past month PTSD symptoms, and questions related to peers (see Measures). Participants had one week to complete the baseline survey. Subsequently, they were asked to complete short daily diary web surveys every day for 30 consecutive days. Following Armeli et al. (2003, 2010), participants had access to web surveys in the early afternoon/evening (11am–10pm) to accommodate college student schedules and to minimize reporting time variation. Surveys took approximately 5–10 minutes to complete.

We achieved excellent retention; on average, participants completed 26.31 (SD = 4.64) daily surveys out of 30 possible days. Approximately 85% of the sample (n=108) completed at least 80% of the daily surveys (i.e., 24 days; modal number of surveys = 30). Moreover, out of a total possible 512 person-weekends (128 participants X 4 weekends) only 30 data points were missing (.06%). Daily surveys were usually completed in the afternoon (Mtime = 3:18pm), consistent with other daily diary studies assessing alcohol behavior in college (e.g., Armeli et al., 2010; O’Grady et al., 2011).

Participant compensation

Participants received $15 to an online retailer for baseline survey completion and either course credit or payment for participation in the daily study, with the compensation proportionally tied to the amount of data provided. Full amount was awarded for completion of more than 75% of the daily ratings (i.e., 23 days; either $30 or 4 course credits). Those who completed less than 75% of the daily ratings were compensated a prorated rate of $1 per daily rating or 1 credit/week.

Measures: Baseline

Demographics

Demographic questions assessed participant race and ethnicity, age, sex, year in school, residence, and Greek affiliation.

Traumatic Life Experiences Questionnaire (TLEQ)

The 23-item TLEQ (Kubany et al., 2000)1 was administered to assess a wide range of lifetime trauma exposure based on the DSM-IV definition of trauma (Criterion A1 and A2). The TLEQ was also used to anchor daily reporting of PTSD symptoms to specific traumatic experiences. This measure has exhibited good validity in college individuals (Kubany et al., 2000).

PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C)

Past month DSM-IV PTSD symptoms were assessed using the 17 item PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers, Huska, & Keane, 1991; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). This measure was designed to assess PTSD symptoms from DSM-IV Criteria B, C, and D in a civilian population and has been validated in college student samples (e.g., Conybeare, Behar, Solomon, Newman, & Borkovec, 2012). Response options are rated on a 5-point scale (range 1–5), with higher scores reflecting greater past-month PTSD symptom severity. Participants were instructed to complete the PCL-C referring to their particular traumatic event(s). PCL-C items were then re-coded as symptom or non-symptom based on empirically derived cut scores to estimate how many participants met diagnostic criteria (i.e., symptoms rated as “3” or “4” (depending on the item) or higher were re-coded to “1” [symptom] and symptoms scored as “2” or “1” were re-coded to “0” [non-symptom]; Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). This yields a symptom count consistent with the DSM-IV conceptualization of PTSD. Reliability was excellent (α=.95).

Alcohol use

Participants reported on the frequency and quantity of drinks consumed in the past 30 days to understand how much and how often drinking was occurring. A Standard Drink Conversion chart was provided to enhance reporting accuracy. Participants were asked “Think of all of the times in the PAST 30 DAYS when you had something to drink. How often have you had some kind of beverage containing alcohol?” Response options ranged from 1 (once in the past month) to 6 (every day). Participants were also asked: “In the PAST 30 DAYS, when you were drinking alcohol, how many drinks did you usually have on any ONE occasion?” Response options ranged from 1 (less than one drink) to 9 (nine or more drinks). Last, participants were asked about binge drinking frequency based on gender (NIAAA, 2004): “In the PAST 30 DAYS, how many times have you had five or more drinks (for males) or four or more drinks (for females) within a 2-hour period?”

Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ)

Negative alcohol-related consequences were measured with the YAACQ (Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006), which assessed whether participants experienced any of 48 consequences within the past month (0 = No; 1 = Yes). Consequences fall into eight domains specific to the college milieu (e.g., Academic, Blackouts). The YAACQ has demonstrated strong test-retest reliability (Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007) and reliability in the present sample was excellent (α=.93).

Emotionally Supportive Peer Group

Participants’ emotionally supportive peer group was assessed consistent with prior research looking at social network and college drinking norms (Lau-Barraco & Collins, 2011; Leonard, Kearns, & Mudar, 2000; Reifman et al., 2006; Wood et al., 2001). Participants were asked to list up to 3 same-college peers who “are available to give you emotional support – for example, someone that you trust and who will not judge you, or someone that will comfort you if you were upset or be there for you in a stressful situation, and/or listen to you talk about your feelings.” Then, for each emotionally supportive peer listed, participants were asked additional questions related to drinking behavior to gauge peer level of use: typical alcohol use in the past 30 days and drinking buddy status (“Do you consider this peer a “drinking buddy,” someone that you get together with on a regular basis to do activities that revolve around drinking, like going to bars or parties?”).

Other Friends/Acquaintances

Participants were also asked to list up to 3 peers that “you consider a friend or an acquaintance, but who you do not go to for support when things are stressful.” For each additional friend/acquaintance listed, participants were asked identical questions related to these friends’ drinking behavior, described above.

Measures: Daily Assessment

PTSD Symptoms

Variation in PTSD symptoms was assessed using the PCL-C (between-person α = .96). Respondents rated how much they were bothered by the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms “in the past 24 hours” on a Likert scale from 0 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Extremely”). The survey was programmed so that all PTSD symptom items referred to the specific traumas endorsed by the participant in their baseline surveys. Each item was summed to get a total daily score representing PTSD symptom severity. Daily scores were then used to create weekday PTSD severity scores by averaging Sunday-Thursday. Weekday PTSD was then used as an independent variable in multilevel models.

Alcohol Consumption

Participants were asked how much they drank “in the past 24hours.” Response options ranged from: 0 drinks to 15 or more drinks (O’Grady et al., 2011). A variable denoting weekend alcohol use was created by averaging Friday and Saturday drinking.2 This was then used as a dependent variable in analyses.

Alcohol Consequences

Surveys also assessed whether participants experienced any of 24 alcohol-related consequences in the past 24 hours using the Brief-YAACQ (0 [No] or 1 [Yes]; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005). The Brief-YAACQ represents a range of alcohol consequences on a spectrum of severity similar to the YAACQ and demonstrates strong psychometric properties (between-person α = .92; Kahler et al., 2005; Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008). A variable representing weekend consequences was created by averaging Friday and Saturday Brief-YAACQ scores and was used as a dependent variable in analyses.

Emotionally Supportive Peer Group

Participants were asked whether they drank with any of their emotionally supportive peers (first names of peers were listed for easy reference) in the past 24 hours. If participants endorsed yes, they were asked to estimate “how much on average did (s)he drink?” (response options ranged from 1drink to ≥15 drinks). Participants were also asked a yes (1)/no (0) question regarding peer encouragement to drink (“Did your emotionally supportive peer(s) offer you a drink in the past 24 hours?”) and a question regarding peer acceptability of drinking (“How acceptable did (s)he think it was to drink in that setting?”; answers ranged from 0 (“Not at all acceptable”) to 3 (“Very acceptable”)). (See Data Analytic Plan for description of how peer variables were created for multilevel analyses).

Other Friends/Acquaintances

Participants were also asked the same questions in reference to their other friends/acquaintances (first names of peers were listed for easy reference). If participants endorsed drinking with these friends in the past 24 hours, they estimated “how much on average did (s)he/they drink?” (response options: 1– ≥15). Participants were also asked whether “Your other friend(s)/acquaintance(s)offered you a drink in the past 24 hours?” and “How acceptable did (s)he/they think it was to drink in that setting?” Description of how these variables were combined for daily analyses is located in the Data Analytic Plan.

Data Analytic Plan

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to assess the within-person relationship between weekday PTSD symptoms and weekend alcohol use and consequences as this approach tests whether individuals differ within themselves across multiple occasions (Singer & Willet, 2003). Missing data at Level 1 was not of concern due to the high rates of participation, and because MLM models use all available data without requiring balanced and equal occasions of measurement across participants. Prior to multilevel analyses, data were assessed for missingness at Level 1 and dependent variables were screened for accuracy of linearity and normality. The weekend alcohol quantity variable was positively skewed and kurtotic (kurtosis > 2) as was the weekend alcohol consequences variable (kurtosis > 13). Thus, we used a Poisson distribution with over-dispersion for all subsequent models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Coefficients for Poisson models generally are presented in Rate Ratios (RR). In the current models, the RR would be interpreted as the proportional increase in drinking outcome per additional PTSD symptom severity experienced. In addition, lagged weekend (i.e., prior weekend) alcohol behavior was entered as a covariate at Level 1, as this helps answer the question of how strongly weekday PTSD severity predicts change in weekend drinking from the previous week.

Aim 1: Evaluate variability and associations among weekday PTSD symptoms, weekend alcohol use (Aim 1a) and weekend alcohol consequences (Aim 1b)

As a preliminary step, unconditional MLM means models were run to test for significant within-person variability in weekend alcohol use and consequences. We hypothesized that the majority of variance in each of these variables would occur at the within-person level. Next, a series of conditional models predicting weekend drinking variables from weekday PTSD symptoms were estimated. These models provided two main pieces of information. First, they tested the average association (i.e., fixed effect), between weekday PTSD symptom severity and weekend drinking variables (i.e., quantity, consequences). Second, models assessed the between-person variability (i.e., random effects) in the within-person relationship between weekday PTSD severity and weekend drinking variables. Level 1 outcome variables included weekend alcohol quantity and consequences and the Level 1 predictor variable across models was weekday PTSD severity (group-mean centered). To control for between-person differences in the endorsement of PTSD symptom severity, we entered the individual’s (uncentered) mean for the predictor variable (i.e., Weekday PTSD symptom severity) as a Level-2 variable in all models (see Results for model equations). Consistent with SMT, we hypothesized that greater weekday PTSD symptom severity would predict higher subsequent weekend drinking and consequences.

Aim 2: Evaluate whether the weekend drinking behavior of one’s emotional support group and other friends/acquaintances moderates the PTSD-alcohol relationship

To test the role of weekend moderators of the PTSD-alcohol relationship, peer variables (i.e., drinking with their peer(s), peer alcohol consumption, peer encouragement to drink, and peer approval of drinking) were included as predictors of weekend alcohol use and consequences in the models described in Aim 1 and in interaction with weekday PTSD symptoms. Models were run separately for emotionally supportive peer drinking and other friend/acquaintance drinking. Four emotionally supportive peer drinking variables were created by combining drinking data from each of the (up to) three peers in the following manner: (1) a dichotomous variable denoting whether the participant drank with any supportive peer, (2) a sum of all supportive peer(s) daily alcohol quantity, (3) a dichotomous variable denoting whether any supportive peer(s) offered the participant a drink, and (4) average supportive peer acceptability of alcohol use. Next, these variables were transformed into weekend variables by averaging Friday and Saturday data. Four parallel variables representing other friends/acquaintances weekend drinking were created and used as moderators in separate analyses. In addition, all of the continuous predictor variables were person-centered prior to creating the interaction term (e.g., weekend peer drinks X weekday PTSD symptom severity). MLM analyses were conducted using HLM 7 software (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & Toit, 2011).3

Results

Descriptive Analysis: Baseline

Approximately 70% of the final sample (n=89) reported experiencing at least one trauma based on the DSM-IV (see Table 1) and 94.5% of the sample (n = 121) experienced at least one trauma based on the DSM-5. The three most common traumas endorsed were: (1) the “sudden and unexpected death of a close friend or loved one” (38.3% of participants), (2) a “loved one surviving a life-threatening or permanently disabling accident, assault, or illness” (30.5%), and (3) experiencing some form of sexual assault as a child or an adult (18%). The average number of PCL-C symptoms reported was 3.57 (range 0–17, SD = 4.56) and approximately 16.4% (n = 21) of participants met symptom criteria consistent with a PTSD diagnosis based on DSM-IV. An additional 14.8% (n = 19) met for partial PTSD (i.e., subthreshold symptomatology assessed as ≥1 symptom in Criteria B, C, and D; Schnurr, Friedman, & Rosenberg, 1993; Stein, Walker, Hazen, & Forde, 1997). The remainder of the sample either reported no PTSD symptoms (33%) or reported a constellation of symptoms not consistent with the PTSD diagnosis (35.8%). Therefore, variability in baseline symptom presentation was achieved.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics at Baseline, Daily, Weekday, and Weekend for Participants and Peers.

| Baseline Variables | M (SD) | Range | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18.84 (1.14) | 18–24 | -- |

| White | -- | -- | 76.6% |

| Female | -- | -- | 50% |

| Trauma - Lifetime | 1.70 (1.89) | 0–9 | -- |

| PTSD Diagnosis | -- | -- | 16.4% |

| PTSD Symptom Count | 3.57 (4.56) | 0–17 | -- |

| PCL-C Total Score | 31.59 (14.39) | 17–82 | -- |

| Past 30-day Drinks Per Occasion | 5.52 (1.80) | 1–9 | -- |

| Past 30-day Drinking Occasions | 2.71 (.87) | 1–5 | -- |

| Binge Once/Week | -- | -- | 44% |

| Past 30-day Alcohol Consequences | 8.82 (8.22) | 0–48 | -- |

| Listed 3 Supportive Peers | -- | -- | 80% |

| Supportive Peer Past 30-day Drinks Per Occasion | 4.96 (1.92) | 0–9 | -- |

| Supportive Peer Past 30-day Drinking Occasions | 2.34 (0.88) | 0–7 | -- |

| Listed 3 Other Friends/Acquaintances | -- | -- | 80% |

| Friends/Acquaintances Past 30-day Drinks Per Occasion | 5.25 (1.74) | 1–9 | -- |

| Friends/Acquaintances Past 30-day Drinking Occasions | 2.67 (0.81) | 0–7 | -- |

|

| |||

| Daily, Weekday, and Weekend Variables | |||

|

| |||

| Daily PTSD symptom severity | 4.27 (9.35) | 0–68 | -- |

| Weekday PTSD symptom severity | 5.09 (9.25) | 0–46 | -- |

| Weekend PTSD symptom severity | 4.49 (9.90) | 0–68 | -- |

| Daily drinks | .96 (2.52) | 0–15 | -- |

|

| |||

| Daily drinks on drinking days | 5.52 (3.38) | 1–15 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekday drinks | .40 (1.61) | 0–15 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekday drinks on drinking days | 1.60 (1.71) | .20–10.33 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekend drinks | 2.54 (3.69) | 0–15 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekend drinks on drinking weekends | 4.61 (2.93) | .50–15 | -- |

|

| |||

| Daily consequences | .53 (2.11) | 0–24 | -- |

|

| |||

| Daily consequences on drinking days | 2.88 (4.16) | 0–24 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekday consequences | .29 (1.75) | 0–24 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekday consequences on drinking days | 1.14 (2.66) | 0–18 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekend consequences | 1.20 (2.77) | 0–24 | -- |

|

| |||

| Weekend consequences on drinking weekends | 2.23 (3.04) | 0–17.50 | -- |

|

| |||

| Daily drinks: Supportive peers | 4.95 (3.28) | 1–15 | -- |

| Weekday drinks: Supportive peers | 3.90 (3.36) | 1–15 | -- |

| Weekend drinks: Supportive peers | 5.62 (3.06) | 1–15 | -- |

| Supportive peer acceptability of drinking | 2.45 (0.81) | 0–3 | -- |

| Weekday acceptability: Supportive peers | 2.21 (.96) | 0–3 | -- |

| Weekend acceptability: Supportive peers | 2.57 (.68) | 0–3 | -- |

| Daily drinks: Friends/Acquaintances | 6.13 (3.21) | 1–15 | -- |

| Weekday drinks: Friends/Acquaintances | 5.31 (3.40) | 1–15 | -- |

| Weekend drinks: Friends/Acquaintances | 6.50 (3.06) | 1–15 | -- |

| Friends/Acquaintances acceptability of drinking | 2.45 (0.83) | 0–3 | -- |

| Weekday acceptability: Friends/Acquaintances | 2.07 (.99) | 0–3 | -- |

| Weekend acceptability: Friends/Acquaintances | 2.60 (.70) | 0–3 | -- |

Note. Final sample = 128. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; PCL-C = PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version; Weekday = Sunday–Thursday; Weekend = Friday–Saturday. Baseline variables capture behavior over the previous 30 days.

Past 30-day drinking rates and consequences experienced at baseline are presented in Table 1. Frequency of weekly binge drinking (44%) and number of consequences experienced in the past month were comparable to rates observed in other samples of college student drinkers (e.g., Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, Schulenberg, & Miech, 2014; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). Most participants (96%) listed at least one supportive peer, 89% listed at least two such peers, and 80% listed three. In addition, approximately 80% of participants considered at least one of their supportive peers a drinking buddy, and of those, 36% considered all three peers a drinking buddy, indicating that the overlap between emotional support and drinking buddy status was quite high (see Table 1 for peer drinking descriptives and Supplemental Material for more peer descriptive information). The majority of participants (86.7%) listed at least one friend/acquaintance at college, 82.8% reported on at least two friends/acquaintances, and 76.6% listed three friends/acquaintances. Similar to supportive peers, the majority of participants (64%) considered at least one of these other friends a drinking buddy. Of these participants, 35% considered all three friends a drinking buddy. Interestingly, participants were significantly more likely to consider a supportive peer a drinking buddy as opposed to other friends/acquaintances (χ2 = 16.24, p < .01).

Descriptive Analysis: Daily, Weekday, and Weekend

The range of days participants reported experiencing any PTSD symptoms varied widely, from zero (n=27) to all days assessed (n=16). Participants reported experiencing at least one symptom on 34% of the days. An averaged total PCL-C score was created to assess how much participants were bothered daily by these symptoms. On average, participants reported being “not at all” to “a little bit” bothered by symptoms (M=.25, SD=.55, range 0–4). Each item was then summed to get a total score representing PTSD symptom severity (M=4.27, SD=9.35, range 0–68; see Table 1). Severity scores were used to create weekday versus weekend PTSD variables, and a comparison between the two indicated that participants experienced slightly more symptom severity on weekdays versus weekends (Mweekday=5.09, Mweekend=4.49, t=2.11, p=.04).

Only 7 participants reported that they never drank during the study and 1 participant reported that he/she drank every assessed day. On average, participants reported drinking on 17% of the days assessed, which translates to drinking approximately one out of every six days. As hypothesized, significantly more drinking took place on the weekends (M = 2.54; SD = 3.69) as opposed to the weekdays (Sunday–Thursday; M = .40, SD = 1.61, t = 16.62, p < .01). In addition, average drinking rates during drinking weekends approximately reached binge threshold (M = 4.61, SD = 2.93) and map onto other college drinking samples assessed at the daily level (Armeli et al., 2003; Kaysen et al., 2014; Merrill, Read, & Barnett, 2013; Rankin & Maggs, 2006) . The number of days participants reported experiencing alcohol consequences varied similarly to daily drinking, with only 17 participants reporting that they never experienced any alcohol consequences during the period of assessment (see Table 1). On average, participants endorsed experiencing an alcohol-related consequence on 12% of the days, which translates to approximately once per week. The average number of consequences experienced on weekends (M = 1.20, SD = 2.77) was significantly more than consequences experienced during the week (M = .29, SD = 1.75; t = 9.09, p < .01). Furthermore, average consequence rates during drinking weekends (M = 2.23, SD = 30.4) are consistent with those observed in other college drinking samples assessed at the weekly level (e.g., Merrill et al., 2013), indicating that the current sample was actively engaging in drinking behavior during the time of assessment.

Participants reported that on drinking days, 59% of those days were with supportive peers. In addition, peers drank significantly more on weekends than weekdays (t = 4.95, p <. 01; see Table 1). On the days participants drank with these peers, 55.6% stated that at least 1 of their supportive peers offered them a drink and 58.8% thought that their supportive peer(s) viewed drinking as “very acceptable.” This percentage was similar regardless of which supportive peer participants drank with (range: 59.8%–66.7%). Participants drank less often with other friends/acquaintances (34.7% of drinking days). However, friends/acquaintances drank significantly more than participants’ supportive peers (t = 2.43, p = .02). Similar to supportive peer drinking, friends drank significantly more on the weekends than weekdays (t = 2.31, p = .02; see Table 1). On days participants drank with these friends, 53.8% of participants stated that at least one of these friends offered them a drink. Participants also reported that the majority of these friends (63.5%) viewed drinking as “very acceptable” on drinking occasions.

AIM 1a Analyses: Weekend Alcohol Quantity as Outcome Variable

Unconditional models suggested that the variance (random effects) was significant at .61 (χ2 = 561.21; p < .001), indicating significant individual differences in weekend drinking among participants. As hypothesized, the majority of variance in weekend alcohol use was within-person (ICC=.23; 77% within-person variability). Weekday PTSD severity was modeled as a randomly-varying Level 1 predictor (group-mean centered) as the association between symptoms and alcohol use was hypothesized to vary across individuals.4 Both mean average weekday PTSD severity at Level 2 and alcohol quantity consumed during the previous weekend at Level 1 (group-mean centered, randomly-varying) were covariates. Final equations were as follows:

In examining fixed effects, weekday PTSD severity at Level 1 did not significantly predict residualized change from weekend to weekend in alcohol use (RR=1.01, 95% C.I. [.96, 1.08], p=.64). However, the significant between-person variability (Variance = .0006, χ2 =76.59, p < .05) suggests that this effect differs across individuals. Interestingly, previous weekend alcohol use significantly predicted the following weekend’s drinking (RR=.80, 95% C.I. [.76, .84], p < .01). This indicates that for every additional drink consumed during a given weekend, there is a 20% decrease in drinking the following weekend. This also indicates that for a decrease in one drink on a given weekend, there is a 25% increase in drinking the following weekend.

AIM 1b Analyses: Weekend Alcohol Consequences as Outcome Variable

Unconditional models indicated that the variance (random effects) was significant at 1.15 (χ2 = 817.32; p < .001), meaning there were significant individual differences in weekend alcohol consequences among participants. The majority of variance in weekend alcohol consequences was within-person (ICC=.40; 60% within-level), signifying the importance of looking at weekend fluctuations. Similar to models described above, weekday PTSD severity was modeled as a randomly-varying Level 1 predictor (group-mean centered) and mean average weekday PTSD severity was modeled as a Level 2 predictor5 with weekend alcohol consequences as the outcome. This model also controlled for Time (randomly-varying at Level 1) 6 and alcohol consequences experienced during the previous weekend (Level 1, group-mean centered).

In examining the fixed effects, average growth rate (time) in weekend alcohol consequences (RR = 1.06, 95% C.I. [.81, 1.40], p = .66) was not significant. Similar to the model predicting weekend alcohol use, weekday PTSD severity (at Level 1) did not predict residualized change from weekend to weekend in alcohol consequences (RR = .99, 95% C.I. [.88, 1.12], p = .92). However, previous weekend alcohol consequences predicted next weekend consequences (RR = .69, 95% C.I. [.62, .78], p < .01). Thus, for every 1-unit increase in consequences experienced during a given weekend, there is a 31% decrease in consequences the following weekend. Moreover, for every 1-unit decrease in consequences experienced, there is a 45% increase in consequences the following weekend. Further, the significant between-person variability that we observed (Variance = .071, χ2 = 103.67, p < .01) reveals differences across individuals. Despite non-significant fixed effects, the significant between-person variability in the within-person effects points to the utility of testing moderators.

AIM 2 Analyses: Peer Alcohol Behavior as a Within-Person Moderator

Moderation analyses looked at how the weekend drinking behaviors of both emotionally supportive friends and other friends moderated the relationship between weekday PTSD symptom severity and weekend alcohol quantity and consequences. Four moderators for each set of peers was assessed: whether the participant drank with that peer(s) that weekend (yes/no), the amount of alcohol that peer(s) drank that weekend, whether the peer(s) offered the participant an alcohol beverage (yes/no) over the weekend, and how acceptable the peer(s) thought it was to drink that weekend. All continuous predictors were person-centered prior to creating the interaction term. Dichotomous moderators were coded as 0 or 1. All models controlled for average weekday PTSD symptom severity at Level 2 and both Time and previous weekend alcohol behavior at Level 1. Significant interactions were plotted using high (one standard deviation above the mean) and low (one standard deviation below the mean) values of the predictor and moderator variables. Because all models used a Poisson distribution, the predicted values were exponentiated (Dawson, 2014; Dawson, 2015).

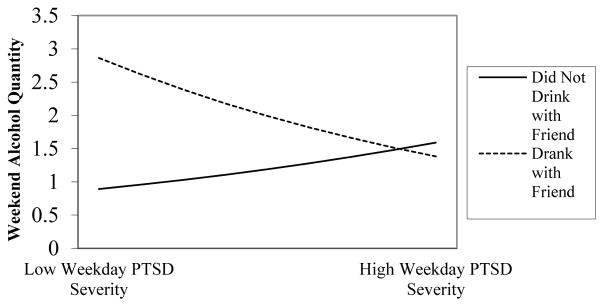

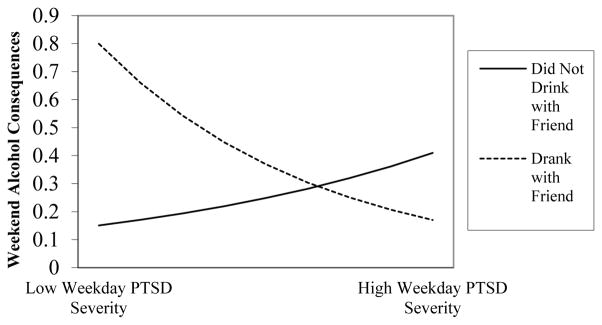

No significant moderators were found when assessing emotionally supportive peer alcohol behavior. However, the analyses looking at other friends/acquaintances’ drinking behaviors yielded significant interaction effects. Drinking with other friends moderated the relationship between weekday PTSD severity and weekend alcohol use and consequences (see Table 2, Figures 1 and 2). It appears that when participants drank with these friends, they were more likely to drink and experience consequences if lower on weekday PTSD severity. When participants did not drink with friends, they were slightly more likely to consume alcohol and experience consequences if higher on weekend PTSD severity.

Table 2. Drinking with other friends/acquaintances as a moderator of weekday PTSD severity and weekend alcohol behavior.

| Variables | Weekend Alcohol Quantity | Weekend Alcohol Con sequences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| β | RR [95% CI] | β | RR [95% CI] | |

| Avg Weekday PTSD – Level 2 | −.011 | 0.99 [0.96, 1.02] | .004 | 1.00 [0.96, 1.05] |

| Time | −.069 | 1.07 [0.94, 1.23] | .054 | 1.06 [0.81, 1.37] |

| Lagged Alcohol Behavior | −.090** | 0.91 [0.88, 0.95] | −.379** | 0.68 [0.63, 0.74] |

| Weekday PTSD Severity | −.009 | 0.99 [0.96, 1.02] | −.031 | 0.97 [0.89, 1.06] |

| Weekend Friend Alc Use | 1.20** | 3.31 [2.22, 4.93] | 1.02** | 2.79 [1.33, 5.85] |

| Weekday PTSD X Weekend Friend Alc Use | −.322** | 0.72 [0.61, 0.86] | −.628** | 0.53 [0.34, 0.84] |

Note. β = Log-transformed coefficient; RR = Rate Ratio; C.I. = Confidence Interval; Avg = Average; PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Alc Use = Used alcohol that weekend (yes/no).

All variables were centered prior to interactions being calculated.

p < .05;

p < .01

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of whether participants drank with “other” friends/acquaintances on the weekday PTSD severity-weekend alcohol quantity relationship.

Figure 2.

Moderating effect of whether participants drank with “other” friends/acquaintances on the weekday PTSD severity-weekend alcohol consequences relationship.

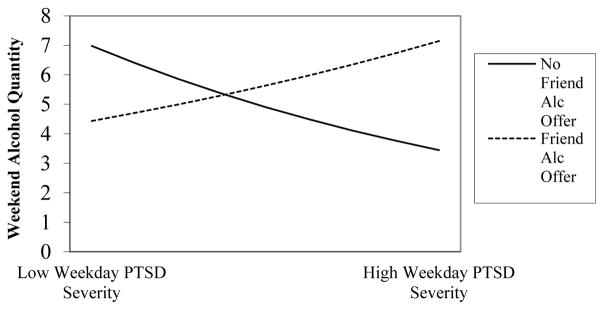

Lastly, drink offers by friends/acquaintances that weekend moderated the weekday PTSD severity to weekend alcohol use relationship (RR = 1.31, 95% C.I. [1.09, 1.56], p < .01; see Figure 3). When participants were offered a drink that weekend, those higher in weekday PTSD severity were more likely to consume alcohol. In contrast, the absence of such offers was associated with a decreased likelihood of drinking for those higher in weekday PTSD.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of “other” friends/acquaintances alcohol offer on the weekdayPTSD severity-weekend alcohol quantity relationship.

Discussion

In the present study, we further elucidate the relationship between PTSD symptoms and drinking behaviors among trauma-exposed college students, and advance the literature by examining how peer drinking behaviors affect this association. Findings add to the nascent ESM literature on the assessment of drinking behaviors and their association with PTSD symptoms, and highlight some of the complexities of these associations. Findings also point to the potential significance of at least some facets of peer influence for PTSD-alcohol associations. We discuss these results and their theoretical and clinical implications below.

Though SMT suggests that alcohol use and related problems should escalate following an increase in symptom severity, within-level weekday PTSD symptom severity did not predict weekend alcohol use or consequences. The literature assessing these associations within an ESM framework has been notably mixed, with some studies finding evidence for SMT associations (e.g., Kaysen et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2014) while others not finding such support (i.e., Cohn et al., 2014).7 Mixed results could be due to the level and type of PTSD symptoms modeled. For example, evidence for PTSD-alcohol associations has more commonly been found in samples with higher levels of PTSD severity (Gaher et al., 2014) and for associations with specific PTSD symptom clusters (Kaysen et al., 2014).8 However, moderation analyses still allowed us to test whether the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol behavior changed as a function of peer influence. Results reflecting these analyses are discussed below.

Peer Alcohol Behavior as a Within-Person Moderator

Interestingly, we found that other friends/acquaintances’ weekend drinking behaviors affected the PTSD-alcohol relationship more so than supportive peer drinking behaviors. Although prior research has found that drinking tends to be influenced more by closer friendships, our data suggest that supportive peers did not play as large of a role in the present study. This could be due to drinking rates, as participants reported that friends/acquaintances consumed more alcohol than supportive peers. Results also indicated that whether one drank with friends/acquaintances moderated the relationship between weekday PTSD severity and weekend alcohol use. When participants drank with these friends, they were more likely to drink and experience consequences if lower on weekday PTSD severity. However, when participants did not drink with friends, they were more likely to consume alcohol and experience consequences if higher on weekday PTSD severity. Thus, friends may protect individuals with higher PTSD severity from harmful consequences that might otherwise accompany this level of symptomatology. Findings underscore the importance of drinking context, as those higher on PTSD severity are drinking and experiencing more consequences when not with friends.

Additionally, whether other friends/acquaintances offered participants a drink moderated the weekday PTSD-weekend alcohol consequences association. When offered a drink, those higher in weekday PTSD severity were more likely to report weekend alcohol consequences. Conversely, when not offered a drink, those higher in weekday PTSD severity were less likely to experience weekend consequences. This finding demonstrates that friends’ alcohol behavior can be both a risk and a protective factor for those higher on PTSD severity. It is possible, then, that even though participants report drinking with these friends less often, they still affect an individual’s drinking behaviors when experiencing greater PTSD symptomatology.

Current findings provide evidence for a nuanced perspective on SMT, and one that seeks to integrate individual and contextual processes. The interaction between context and self-medication processes has seldom been studied, in part because these have been viewed as orthogonal explanations in predicting substance use. Our findings are thus a novel addition to the literature, and suggest that those whose friends actively influence drinking (i.e., offer drinks) and are elevated on PTSD are more likely to engage in risky drinking. This is consistent with findings from Hussong and Hicks (2003) who showed that negative mood is related to increased drinking when close friends are heavy drinkers. These studies highlight the importance of considering peer influences when seeking to understand how distress leads to drinking.

Interestingly, drinking and consequences during a given weekend were inversely associated with drinking and consequences the following weekend, pointing to the possibility that individuals are self-correcting (adjusting their drinking behavior based on experience). This is somewhat consistent with prior work showing that college students learn to modify their alcohol behavior based on recent drinking events (Merrill et al., 2013).

Clinical Implications

The findings have potential implications for interventions on college campuses. Brief interventions based on motivational interviewing techniques have garnered the most support in the literature (Larimer & Cronce, 2007; Carey, Carey, Henson, Maisto, & DeMartini, 2011). However, intervention effects tend to decline over time. This has led to tailoring treatment in order to maximize effects, such as modifying interventions for those with psychological distress (e.g., Monahan et al., 2013) or incorporating peer influences on alcohol use (e.g., Reid, Carey, Merrill, & Carey, 2015). The present study’s findings can add to this literature by underscoring the nuanced risk that peer behavior imparts on those experiencing symptoms related to a trauma. Distinguishing between one’s supportive peers and other friends/acquaintances might be fruitful for clinicians, as the present study suggests that supportive peers’ drinking behaviors may not affect the PTSD-alcohol relationship as much as other friends’ drinking. One goal of a brief intervention is to introduce behavioral strategies to reduce the risk of drinking consequences. Clinicians could have the individual list “safer” peers to drink with if one decides on drinking, and to reinforce ways to refuse drinks if offered. However, it is important to bear in mind that significant effects in this study were small-moderate. Thus, replication is needed before strong conclusions regarding clinical interventions can confidently be drawn.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. Foremost among these is that temporal ordering at the daily level could not be ascertained, as PTSD symptoms and alcohol behavior were measured at the same time. It was in part for this reason that we examined weekday PTSD symptoms predicting subsequent weekend alcohol behavior. This latter analysis provided clearer delineation of temporal associations between PTSD severity and alcohol outcomes and addressed the importance of focusing on when risky drinking most likely occurs in college (i.e., weekends). Further, though longer than other daily studies assessing similar constructs (Cohn et al., 2014; Gaher et al., 2014), the time period of 30 days (i.e., four weekends) was relatively brief. A longer assessment period may have allowed us to capture the hypothesized associations posited in Aim 1. In addition, with a more symptomatically severe sample, stronger evidence for self-medication processes may have emerged. As noted above, peer influences on risk behaviors in emerging adulthood are far from uniform. In the present study, our aim was to delineate the drinking risk these peers might confer on those presenting with greater PTSD symptoms. Other beneficent effects of peers also are possible, and exploration of these more positive effects will be an interesting direction for future research. In addition, we assessed peer drinking behavior by asking participants. Participants reported, on average, that peers drank slightly more than they did. It is well documented in the college drinking literature (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2003; Lewis & Neighbors, 2004; Neighbors, Dillard, Lewis, Bergstrom, & Neil, 2006) that individuals often overestimate the drinking of their peers. As we did not corroborate this information with peers (i.e., collateral reports), we cannot know whether the estimations reported by our participants reflect the actual drinking behaviors of peers, or the kinds of overestimations that have been documented in prior work. However, the literature also shows that college individuals are quite accurate in estimating the drinking behavior of close peers (Hagman, Cohn, Noel, & Clifford, 2010). As such, drinking rates of peers reported in the present study may be slight estimates, but are most likely a reasonable proxy for friend drinking behavior. Additionally, the sample consisted mostly of individuals under the legal drinking age. It is possible that the current findings would be different for those 21 and over, as these students may be more likely to drink alone and, thus, less influenced by peer alcohol use. Lastly, it should be noted that factors such as coping motivations for drinking (e.g., drinking motives) and self-efficacy to resist drinking have been found to affect associations between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use/consequences at the daily level (Possemato et al., 2015; Simpson et al., 2014). Examination of these kinds of moderating factors will be an interesting next step for future work looking at the proximal effect of PTSD on alcohol use in non-clinical populations. It also will be helpful to delineate how and when different moderators are most influential to understand when and under which circumstances PTSD most likely leads to risky drinking.

Conclusions

Contrary to self-medication hypotheses, the present findings indicated that weekday PTSD symptom severity did not predict subsequent weekend alcohol use behavior. However, the findings also suggested that the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and alcohol use behavior was significantly affected by peer drinking behavior. Moreover, the type of friend and type of influence (active versus passive) seemed to be an important distinction. Emotionally supportive peer drinking behaviors were not a risk factor for one’s own drinking unlike other friends/acquaintances’ drinking. Identifying peers who may exert a more toxic influence and reinforcing one’s ability to refuse drink offers could reduce harm associated with alcohol use when PTSD symptoms are more severe. With these findings as a starting point, future studies that test these processes in higher severity samples (e.g., treatment-seeking individuals) and over a longer timeframe may reveal more information still about the ways in which significant others may impact PTSD-alcohol associations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (F31 AA022272; T32 AA007453) and The Mark Diamond Research Fund from the University at Buffalo awarded to Rachel Bachrach. All views presented in this article are the sole responsibility of the authors, and not the sources of funding. The ideas and data appearing in this article were presented at the 2014 meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism in Bellevue, WA. An abstract from this poster presentation was published in a journal supplement associated with this meeting (Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 38, 183A). These data also appear in the first author’s doctoral dissertation at the University at Buffalo. We would like to thank Kate Carey, Craig Colder, and Debra Kaysen for their helpful comments on study design and data analysis.

Footnotes

Format adapted and reprinted by R. Bachrach, University at Buffalo, for use in specific investigation, by permission of the publisher, Western Psychological Services, 625 Alaska Avenue, Torrance, California 90503, U.S.A. All rights reserved.

Items were re-coded so that data collected on day X reflected behavior on day X-1 (e.g., surveys filled out on Sundays were re-coded as Saturday data). In looking at daily drinking averages (see Supplemental Material, Figures 1 and 2), we are confident that this was the most accurate way to code the data, as peak drinking occurred on recoded Friday and Saturday. Moreover, daily drinking averages for non-weekend days were much lower than weekend days, mapping onto typical college drinking patterns (e.g., Del Boca et al., 2004; Tremblay et al., 2010).

To ensure unique effects of PTSD, all MLM analyses controlled for trait Neuroticism as measured by the Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999) at Level 2. However, results remained the same both with and without controlling for neuroticism. Therefore, final results presented are those without controlling for trait negative affect.

Time was included as a Level 1 predictor in a separate partially conditional model to assess whether the effect of drinking across time varied randomly between people. This model did not evidence a significant growth rate (β00 = −.06, t = −1.52, p = .13), indicating no linear change in weekend alcohol use over the period of assessment. Due to the non-significant fixed effect of Time, this was not controlled for in the final fully conditional model. In addition, Gender was included as a Level 2 predictor in a subsequent partially conditional model, which was non-significant (β01 = .12, t = .72, p = .47). Thus, gender was also not controlled for in this final model.

Gender was included at Level 2 in a subsequent partially conditional model, which was not significant (β01 = −.44, t = −1.85, p = .07). Final models were run both with and without gender and results did not change. Thus, results presented here do not control for gender for parsimony.

Time was included at Level 1 in a separate partially conditional model to assess whether the effect of consequences across time varied randomly between people. This model did not evidence a significant growth rate (β10 = −.06, t = −.95, p = .34), indicating there was not linear change in weekend alcohol consequences over time. However, the variance in the growth rate across time was significant (Variance = .25, χ2 =211.89; p < .001), signifying that individuals vary significantly from each other in the linear rate of change in alcohol consequences over the assessed weekends. Due to this significant variability, time was controlled for in the fully conditional model.

Analyses looking at daily PTSD-alcohol associations were run to directly compare our findings with other ESM studies. These models were non-significant (ps > .05), indicating that daily PTSD severity and alcohol behavior did not covary.

To compare the present findings with Kaysen et al.’s (2014) more directly, analyses were re-run to assess whether PTSD symptom clusters covaried with drinking behaviors. Main effects were non-significant; however, random effects for the avoidance/numbing cluster (Variance = .37, χ2 = 224.79, p < .01) and hyperarousal cluster (Variance = .38, χ2 = 119.33, p = .02) were significant, suggesting the within-person relationship between these symptom clusters and consequences varies between people, lending itself nicely to testing between-level moderation (which was beyond the scope of this paper).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. revised. [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Conner TS, Cullum J, Tennen H. A longitudinal analysis of drinking motives moderating the negative affect-drinking association among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:38–47. doi: 10.1037/a0017530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armeli S, Tennen H, Todd M, Carney MA, Mohr C, Affleck G, Hromi A. A daily process examination of the stress-response dampening effects of alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:266–276. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:235–253. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avant EM, Davis JL, Cranston CC. Posttraumatic stress symptom clusters, trauma history, and substance use among college students. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20:539–555. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2011.588153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach RL, Merrill JE, Bytschkow KM, Read JP. Development and initial validation of a measure of motives for pregaming in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach RL, Read JP. The role of post-traumatic stress and problem alcohol involvement in university academic performance. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68:843–859. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behavior Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. How the quality of peer relationships influences college alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006;25:361–370. doi: 10.1080/09595230600741339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Schultz LR. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Ecker AH, Proctor SL. Social anxiety and alcohol problems: The roles of perceived descriptive and injunctive peer norms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Henson JM, Maisto SA, DeMartini KS. Brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students: Comparison of face-to-face counseling and computer-delivered interventions. Addiction. 2011;106:528–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn A, Hagman BT, Moore K, Mitchell J, Ehlke S. Does negative affect mediate the relationship between daily PTSD symptoms and daily alcohol involvement in female rape victims? Evidence from 14 days of interactive voice response assessment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:114–126. doi: 10.1037/a0035725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conybeare D, Behar E, Solomon A, Newman MG, Borkovec TD. The PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version: Reliability, validity, and factor structure in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68:699–713. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JF. Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business Psychology. 2014;29:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JF. Interpreting interaction effects. 2015 [Statistical website]. Retrieved from http://www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm.

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood AM, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Weathers FW, Eakin DE, Benson TA. Substance use behaviors as a mediator between posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health in trauma-exposed college students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:234–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaher RM, Simons JS, Hahn AM, Hofman NL, Hansen J, Buchkoski J. An experience sampling study of PTSD and alcohol-related problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:1013–1025. doi: 10.1037/a0037257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M, Litz B, Hsu J, Lombardo T. Psychometric properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment. 2004;11:330–341. doi: 10.1177/1073191104269954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagman BT, Cohn AM, Noel NE, Clifford PR. Collateral informant assessment in alcohol use research involving college students. Journal of American College Health. 2010;59:82–90. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.483707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeppner BB, Barnett NP, Jackson KM, Colby SM, Kahler CW, Monti PM, … Fingeret A. Daily college student drinking patterns across the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:613–624. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(Suppl 16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska B, Delahanty DL. Application of the stressor-vulnerability model to understanding posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol related problems in an undergraduate population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:734–746. doi: 10.1037/a0027584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Hicks RE. Affect and peer context interactively impact adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:413–426. doi: 10.1023/a:1023843618887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Hicks RE, Levy SA, Curran PJ. Specifying the relations between affect and heavy alcohol use among young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:449–461. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Vol. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-Day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Towards efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;25:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Atkins D, Simpson T, Stappenbeck C, Blayney J, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Proximal relationships between PTSD symptoms and drinking among female college students: Results from a daily monitoring study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:62–73. doi: 10.1037/a0033588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The Self-Medication Hypothesis revisited: The dually diagnosed patient. Primary Psychiatry. 2003;10:47–48. 53–54. Retrieved from http://www.primarypsychiatry.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SY, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: Individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999–2006. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau-Barraco C, Collins RL. Social networks and alcohol use among nonstudent emerging adults: A preliminary study. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Kearns J, Mudar P. Peer networks among heavy, regular, and infrequent drinkers prior to marriage. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:669–673. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Weathers FW, Flood AM, Eakin D, Benson T. The utility of the PAI and the MMPI-2 for discriminating PTSD, depression, and social phobia in trauma-exposed college students. Assessment. 2007;14:181–195. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Barnett NP. The way one thinks affects the way one drinks: Subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences predict subsequent change in drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:42–51. doi: 10.1037/a0029898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Vogt DS, Mozley SL, Kaloupek DG, Keane TM. PTSD and substance-related problems: The mediating roles of disconstraint and negative emotionality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:369–379. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan CJ, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Martens MP, Murphy JG. The impact of elevated posttraumatic stress on the efficacy of brief alcohol interventions for heavy drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1719–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naragon-Gainey K, Simpson TL, Moore SA, Varra AA, Kaysen DL. The correspondence of daily and retrospective PTSD reports among female victims of sexual assault. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24:1041–1047. doi: 10.1037/a0028518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. Bethesda, MD: National Insitute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2004. (NIH Publication No. 04-5346) [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:556–565. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O’Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, Fossos N. The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:576–581. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady MA, Cullum J, Tennen H, Armeli S. Daily relationship between event-specific drinking norms and alcohol use: A four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:633–641. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, Rivers AJ, Morgan CA, Southwick SM. Psychosocial buffers of traumatic stress, depressive symptoms, and psychosocial difficulties in veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom: The role of resilience, unit support, and post-deployment social support. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;120:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato K, Maisto SA, Wade M, Barrie K, McKenzie S, Lantinga LJ, Ouimette P. Ecological momentary assessment of PTSD symptoms and alcohol use in combat veterans. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29:894–905. doi: 10.1037/adb0000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin LA, Maggs JL. First-year college student affect and alcohol use: Paradoxical within-and between-person associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:925–937. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9073-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R, Toit M. HLM 7: Hierarchical Linear and Non-Linear Modeling. Chicago: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Bachrach RL, Wright AGC, Colder CR. PTSD symptom course during the first year of college. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2016;8:393–403. doi: 10.1037/tra0000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE, Ouimette P, White J, Swartout A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms predict alcohol and other drug consequence trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:426–439. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–178. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Ouimette P, White J, Colder C, Farrow S. Rates of DSM–IV–TR trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among newly matriculated college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2011;3:148–156. doi: 10.1037/a0021260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Capone C. A prospective investigation of relations between social influences and alcohol involvement during the transition into college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:23–34. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid AE, Carey KB, Merrill JE, Carey MP. Social network influences on initiation and maintenance of reduced drinking among college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:36–44. doi: 10.1037/a0037634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifman A, Watson WK, McCourt A. Social networks and college drinking: Probing processes of social influence and selection. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32:820–832. doi: 10.1177/0146167206286219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis. 2. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter LA, Weatherill RP, Krill SC, Orazem R, Taft CT. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, depressive symptoms, exercise, and health in college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5:56. doi: 10.1037/a0021996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Rosenberg SD. Premilitary MMPI scores as predictors of combat-related PTSD symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:479–483. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]