Abstract

This is the first large-scale study to define the injured population and examine associated injuries for patients with tibial shaft fractures. Patients over 18 years of age in the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) who presented with tibial shaft fractures during 2011 and 2012 were identified. Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), mechanism of injury (MOI), injury severity score (ISS), and specific associated injuries were described. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify predictors of mortality.

Keywords: Tibial shaft, Tibial shaft fracture, Mechanism of injury, Injury severity, Associated injuries, Mortality

A total of 19,312 males and 8394 females who had sustained tibial shaft factures were identified. The age distribution was bimodal with peaks at around 20 and 50 years of age. The median CCI for these age groups increased with increasing age. The median ISS was in the 0–9 range for all age groups. Falls were common in the older age groups, while motor vehicle accidents were more common in the younger age groups.

Overall, 59.6% of tibial shaft fracture patients had at least one associated injury (58.2% of patients had at least one other bony fracture, and 16.7% of patients had at least one internal organ injury). Inhospital mortality was more associated with the presence of an associated injury (chi-squared = 268.3) than age (chi-squared = 86.0) or CCI (chi-squared = 0.2).

Overall, the patient population sustaining tibial shaft fractures and their associated injuries were characterized. The importance of such associated injuries is underscored by the fact that mortality was more associated with associated injuries than patient age or comorbidities.

1. Introduction

Tibial shaft fractures occur with an incidence of 16.9/100,000/year.1 They are associated with significant short- and long-term morbidities,2 ranging from acute compartment syndrome to chronic leg and knee pain.3 Furthermore, tibial shaft fractures in working-age adults have been shown to have a significant financial impact, both in terms of direct medical costs and lost productivity.4

As with other orthopaedic injuries, several studies have characterized patients with tibial shaft injuries in terms of age, gender, mechanism of injury (MOI) and fracture type. One such study by Larsen et al. found that men have a higher frequency of fractures while participating in sports activities, while women have a higher frequency while walking and during indoor activities.1 Another study by Court-Brown and McBirnie found that the majority of tibial shaft fractures were caused by falls from height and road-traffic accidents.5 However, both of these studies may be limited by their population sizes (both under 600) or regional factors (both done at single institutions).

In the orthopaedic trauma assessment, it is helpful to know the likelihood of associated injuries in order to optimize evaluations and ensure appropriate management. For example, in the setting of a calcaneus fracture, the strong association with vertebral column injury is often considered.6 Similarly, with open clavicle fractures, pulmonary and cranial injuries are important to suspect and recognize early.7 Although a few studies have examined injuries associated with tibial shaft fractures such as ankle, posterior malleolus, and ligamentous injuries,8, 9, 10, 11 no previous study has characterized overall bony and internal organ injuries that are associated with tibial shaft fractures.

The aim of the present study is to use a large, national sample of adult trauma patients with tibial shaft fractures in order to characterize the patient population, comorbidity burden (modified Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI]), MOI, injury severity score (ISS), and specific associated injuries for adult patients with tibial shaft fractures. It is believed that a better understanding of such variables would help health care providers optimize patient evaluation and management.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient cohort

The National Trauma Data Bank Research Data Set (NTDB RDS) was used to identify patients for this study. This database is compiled from several hundreds of trauma centers around the US and contains administrative and registrar-abstracted data on over five million cases.12 Data files are processed through a validation phase to ensure reliability and consistency of the data used for research.12

The inclusion criteria for patients in this study were: (1) hospital admission during years 2011 and 2012, (2) over 18 years of age, and (3) an International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision code for tibial shaft fracture (823.20, 823.22, 823.30, 823.32). A waiver was issued for this study by our institution’s Human Investigations Committee.

2.2. Patient characteristics

Age was directly abstracted from the database. After evaluation of the age distribution, subsequent analyses were done with age groups defined based on clusters in the population (18–39 years, 40–64 years, 65+ years).

The following comorbidities were directly extracted from the database: hypertension, alcoholism, diabetes, respiratory disease, obesity, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, prior cerebrovascular accident, liver disease, functionally dependent status, cancer, renal disease dementia, and peripheral vascular disease. From these patient characteristics, a modified CCI13 that has been shown to have comparable predictive value to the original CCI was calculated.14 Modified CCI was computed based on an algorithm previously described by an earlier study by Samuel et al.15

2.3. Injury characteristics

ISS is an overall assessment of body trauma severity based on the Abbreviated Injury Scale.16 This is a variable that was directly abstracted from the NTDB RDS data set.

The categorizations for MOI were “fall”, motor vehicle accident (“MVA”), or “other”. Patients with a fall mechanism of injury were determined based on the following ICD-9 e-code ranges: 880.00–889.99, 833.00–835.99, 844.7, 881, 882, 917.5, 957.00–957.99, 968.1, 987.00–987.99. Patients with an MVA mechanism of injury were determined based on the following ICD-9 e-code ranges: 800–826, 829–830, 840–845, 958.5, and 988.5. Patients included in this MVA category were involved in accidents as motor vehicle drivers/passengers, motorcyclists, bicyclists, or pedestrians. All other e-codes were counted as “other”.

For associated injuries, ICD-9 diagnosis codes that were used to identify associated bony and internal organ injuries. It is important to note that based on this data set, it could not be distinguished whether proximal and distal tibia associated injuries were contiguous (extensions of the same fracture line) or indicative of segmental injuries. Thus, these were not included as “associated injuries” because it could not be determined if they were separate from the primary injury.

Mortality data was obtained directly from NTDB RDS. This was based on whether the patient died in the emergency department or the hospital prior to discharge.

2.4. Data analysis

Adobe® Photoshop® CS3 (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, California) was used to illustrate the associated injury frequencies by shadings on the skeleton and internal organ figures. In these figures, darker shadings represent higher frequencies of associated injury.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata® version 13.0 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the association of age, modified CCI, and various associated injuries with mortality. Chi-square statistics for associations with mortality were obtained from Wald tests by using the “test” command following logistic regression on Stata. All tests were two-tailed and a two-sided α level of 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

A total of 27,706 adult patients (19,312 males and 8394 females) with tibial shaft fractures were identified. There were 16,896 (61.0%) closed fractures and 10,810 (39.0%) open fractures.

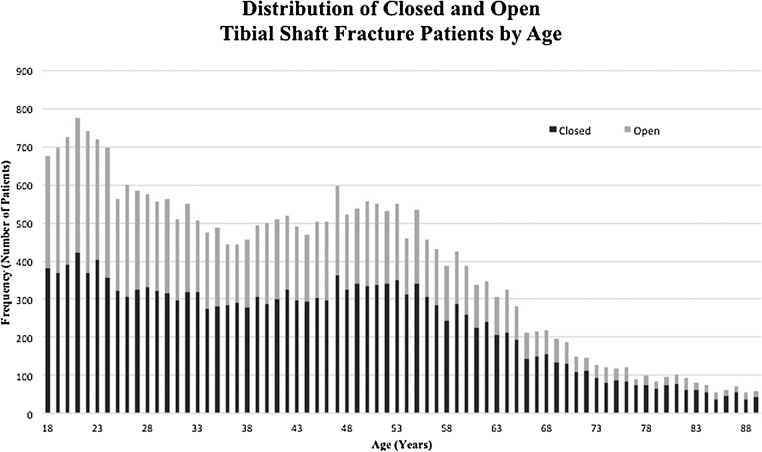

The distributions of open and closed fractures are shown by age in Fig. 1. This distribution overall appeared bimodal with peaks at around 20 and 50 years of age. Based on this age distribution noted for these injuries, the decision was made to analyze the population by age categories (18–39, 40–64 and 65+). More young adults (18–65) were males, while more older adults (65+) were females as shown in Table 1. The medians for modified CCI were 0, 2, and 4 for ages 18–39, 40–64, and 65+, respectively (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of open and closed tibial shaft fracture patients by age.

Table 1.

Age and Gender Distribution.

| Male | Female | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–39 | 9724 | 3121 | 12,845 |

| 40–65 | 8144 | 3598 | 11,742 |

| 65+ | 1444 | 1675 | 3119 |

| Total | 19,312 | 8394 | 27,706 |

Table 2.

Distribution of Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

| CCI | Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–39 | 40–64 | 65+ | Total | |

| 0 | 93.41% | 3.85% | 0% | 44.94% |

| 1 | 5.73% | 38.70% | 0% | 19.06% |

| 2 | 0.64% | 35.54% | 0% | 15.36% |

| 3 | 0.11% | 14.95% | 26.55% | 9.37% |

| 4 | 0.03% | 4.42% | 42.16% | 6.63% |

| > = 5 | 0.09% | 2.55% | 31.29% | 4.64% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Note: Underlined values represent median CCI values for each age group.

3.2. Injury characteristics

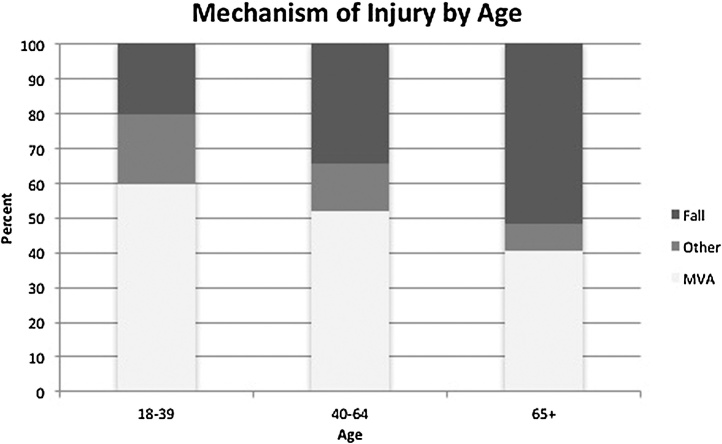

The median ranges for ISS were in the 0–9 range for the three age categories (Table 3). In terms of mechanism of injury distributions, it is noted that ages 18–39 predominantly suffered MVAs, while the elderly (65+) primarily suffered falls (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Distribution of Injury Severity Score (ISS).

| ISS | Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–39 | 40–64 | 65+ | Total | |

| 0–9 | 57.28% | 59.95% | 65.5% | 59.33% |

| 10–19 | 25.61% | 23.37% | 19.27% | 23.94% |

| 20–29 | 10.07% | 9.94% | 9.49% | 9.95% |

| 30+ | 7.05% | 6.75% | 5.74% | 6.77% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Note: Underlined values represent median ISS values for each age group.

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of injury distribution of tibial shaft fracture patients by age.

Frequencies of associated injuries were analyzed by age group (Table 4). The frequencies were overall similar across the ages for all associated injuries, although there was a slight general decline in associated injury frequency as age increased. For example, head injury frequency declined as age increased (18.09% for 18–39; 16.79% for 40–64; 14.33% for 65+). However, ribs/sternum injury frequency showed the opposite trend, with some increase with increased age.

Table 4.

Percent Incidence of Injuries for Each Age Group.

| 18–39 | 40–64 | 65+ | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head Injury | 18.09 | 16.79 | 14.33 | 17.12 |

| Skull Fracture | 10.26 | 9.32 | 6.06 | 9.39 |

| Intracranial Injury | 11.61 | 11.13 | 10.68 | 11.3 |

| Spinal Injury | 12.58 | 15.45 | 14.3 | 13.99 |

| Cervical Spine | 3.54 | 5.25 | 5.87 | 4.53 |

| Thoracic Spine | 3.67 | 5.16 | 4.62 | 4.41 |

| Lumbar Spine | 6.89 | 8.22 | 6.32 | 7.39 |

| Sacral Spine | 3.38 | 3.48 | 3.56 | 3.44 |

| Ribs/Sternum | 11.07 | 17.4 | 18.24 | 14.56 |

| Pelvic Fracture | 9.25 | 9.88 | 9.27 | 8.48 |

| Acetabulum | 4.31 | 4.33 | 2.85 | 4.16 |

| Pubis | 3.75 | 4.63 | 5.26 | 4.3 |

| Ilium | 1.19 | 1.5 | 1.64 | 1.37 |

| Ischium | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.29 |

| Upper Extremity Fracture | 16.26 | 16.64 | 15.45 | 16.33 |

| Clavicle | 2.76 | 3.49 | 3.75 | 3.18 |

| Scapula | 3.01 | 3.71 | 2.66 | 3.27 |

| Humerus | 3.95 | 4.52 | 4.71 | 4.28 |

| Proximal Humerus | 1.4 | 2.38 | 2.92 | 1.99 |

| Humeral Shaft | 1.73 | 1.32 | 1.06 | 1.48 |

| Distal Humerus | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.8 |

| Radius/Ulna | 7.05 | 6.69 | 5.96 | 6.77 |

| Proximal Radius/Ulna | 1.74 | 1.75 | 1.06 | 1.67 |

| Radial/Ulnar Shaft | 2.6 | 2.34 | 2.05 | 2.43 |

| Distal Radius/Ulna | 3.13 | 3.13 | 2.92 | 3.1 |

| Hand | 4.34 | 4.05 | 3.46 | 4.12 |

| Lower Extremity Fracture | 39.73 | 48.98 | 46.3 | 44.39 |

| Other Femur Fracture | 11.55 | 10.02 | 9.84 | 10.71 |

| Proximal Femur | 2.48 | 3.33 | 3.24 | 2.92 |

| Femoral Shaft | 7.57 | 4.95 | 3.43 | 5.99 |

| Distal Femur | 2.55 | 3.53 | 4.1 | 3.14 |

| Patella | 2.2 | 2.11 | 2.02 | 2.14 |

| Tibia/Fibula Fracture | 27.88 | 39.48 | 37.83 | 33.92 |

| Proximal Tibia/Fibula | 10.41 | 18.56 | 17.95 | 14.71 |

| Ankle | 14.33 | 18.57 | 18.34 | 16.58 |

| Foot | 9.97 | 10.01 | 7.02 | 9.65 |

| Thoracic Organ Injury | 13.87 | 12.27 | 11.51 | 12.93 |

| Heart | 0.32 | 0.6 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Lung | 13.55 | 11.8 | 11.03 | 12.52 |

| Pneumothorax | 8.19 | 8.19 | 8.14 | 8.19 |

| Diaphragm | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.49 |

| Abdominal Organ Injury | 9.99 | 8.21 | 6.41 | 8.83 |

| GI Tract | 2.38 | 2.29 | 1.51 | 2.25 |

| Liver | 4.43 | 2.75 | 1.99 | 3.44 |

| Spleen | 4.15 | 3.03 | 1.92 | 3.43 |

| Kidney | 2.13 | 1.42 | 0.96 | 1.7 |

| Pelvic Organ Injury | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.67 | 0.92 |

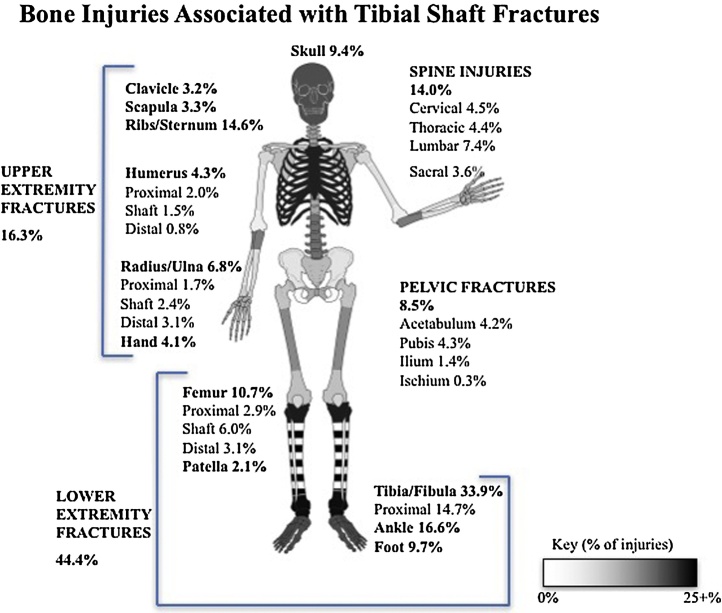

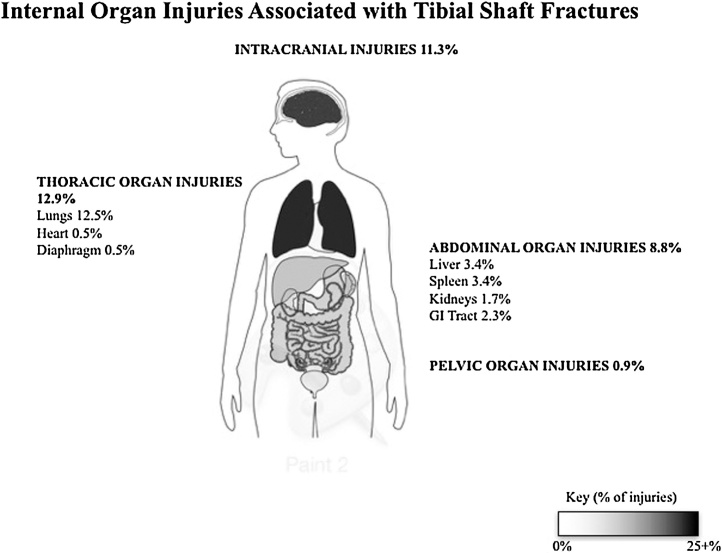

Because similar frequencies of associated injuries were found across the age groupings, the population was considered as a whole to graphically represent the frequencies of bony (Fig. 3) and internal organ (Fig. 4) injuries that accompany tibial shaft fractures. It was found that the three most common bony injuries outside of the tibia/fibula shaft region are ankle (16.58%), ribs/sternum (14.56%), and spine (14.0%) fractures. The two most common internal organ injuries were lung (12.52%) and intracranial (11.3%) injuries. Overall, 59.6% of tibial shaft fracture patients had at least one associated injury (58.2% of patients had at least one other bony fracture, and 16.7% of patients had at least one internal organ injury).

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of percentages of adult (over 18 years old) tibial shaft fracture patients with incidence of associated bony injuries in different body regions. Darker shadings in grayscale correspond to higher frequencies of associated injuries.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of percentages of adult (over 18 years old) tibial shaft fracture patients with incidence of associated internal organ injuries in different body regions. Darker shadings in grayscale correspond to higher frequencies of associated injuries.

To determine the impact of associated injuries versus patient factors (age and CCI) on inhospital mortality, a multivariate regression analysis was conducted (Table 5). Mortality was more associated with the presence of an associated injury (chi-squared = 268.3) than age (chi-squared = 86.0) or CCI (chi-squared = 0.2). In fact, controlling for age and CCI, the odds of mortality with at least one associated injury is over 12-fold compared to without any associated injuries.

Table 5.

Multivariate Analysis of Effects of Associated Injuries on Mortality.

| Outcome: Mortality | Multivariate Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Chi-square statistic* | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (reference = 18–39) | 86.01 | <0.05 | ||

| 40–64 | 1.32 | 1.13–1.55 | ||

| 65+ | 3.01 | 2.46–3.67 | ||

| CCI (reference = 0) | 0.17 | 0.68 | ||

| 1 | 0.65 | 0.51–0.82 | ||

| 2 | 0.81 | 0.52–1.25 | ||

| 3 | 1.36 | 0.80–2.31 | ||

| 4 | 0.70 | 0.22–2.24 | ||

| 5+ | 2.33 | 1.27–4.26 | ||

| Associated Injuries (reference = No Associated Injuries) | 268.31 | <0.05 | ||

| Presence of At Least One Associated Injury | 12.93 | 9.53–17.54 | ||

The Chi-statistics were determined from Wald tests (using the “test” command on Stata after multivariate logistic regression), which were used to determine the relative strengths of the independent associations of three variables (age, CCI, and the presence of any associated injury) with mortality.

4. Discussion

Tibial shaft fractures are common injuries. While several studies have been done regarding the optimal method of treatment for tibial shaft injuries, little work has explored the rate and impact of tibial shaft fracture associated injuries.

Due to distraction, associated injures can be missed on preliminary trauma surveys if not specifically considered. Rapid identification and treatment of such injuries is important to optimize patient care. Thus, the primary goals of this study were to define patient characteristics, MOI, and associated injuries for a large patient population sustaining tibial shaft fractures. The secondary goal of the study was to evaluate the impact of such associated injuries on an important clinical endpoint–inhospital mortality–relative to other patient factors.

Our research sample from the National Trauma Database (NTDB) included 27,706 tibial shaft fracture patients. Overall, the age distribution of our population was bimodal, with peaks at ages 21 and 47 years of age (Fig. 1). There were nearly twice as many male patients than female patients, with the younger population especially favoring male over female subjects (Table 1). Furthermore, there were few elderly subjects past age 65. Based upon the bimodal and nonuniform age distribution, age categories of 18–39, 40–64, and 65+ were created, as it was suspected that these different categories may be representing distinct patient populations.

Our suspicions were confirmed when analyzing MOI (Fig. 2), as the older population tended to suffer injury predominantly from falls, whereas the younger populations were mostly injured from motor vehicle accidents. This trend may be explained by the loss of bone strength typically exhibited in elderly patients. Whereas a tibial shaft fracture in a young patient would characteristically require a high-energy fall, relatively lower energy falls can cause the injury in an elderly person.

To further gain an understanding of our subject population, the individual comorbidities were extracted, along with the Injury Severity Score (ISS) for each patient. Comorbidities were converted to the modified Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), a single value that could be used in multivariate analysis (Table 2). CCI was an effective means to control for the relative health of the subjects while analyzing different variables for their effect on patient morbidity. For our population, CCI increased linearly with increasing age.

ISS was also recorded as a tool to convert the severity of associated injuries for the population into a single variable. For our study, all three age categories tended to exhibit patients with mostly ISS values of 0–9 (Table 3), indicating that most patients have few severe associated injuries. However, a slight increase in frequency of higher ISS values was found in the younger population, suggesting that younger patients are more likely to suffer from extra-tibial injuries.

Similar to the trend with ISS, the rate of associated injuries did not show any significant or abrupt changes based upon age category (Table 4). A slight decrease in associated injuries occurred as age increased, but even this trend was not present throughout this study, as seen by the increasing rate of rib fractures in elderly patients. Because there were no drastic differences in associated injuries based upon age group, the entire population’s associated injury data were transformed into a single visual format (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Darker shades on respective body parts correlate with higher rates of associated injuries. The most common bony injuries were ankle fractures. Although the high rate of ankle fractures may be expected based on proximity to the primary injury (tibial shaft fracture), other bony injuries of note that were further from the tibia include spine injuries (13.99%), skull fractures (9.39%), and upper extremity fractures (16.33%). Even though approximately 1/5 of tibial shaft fractures have an accompanying upper extremity fracture, there was no specific upper extremity bone that was most commonly injured. The most common soft tissue injuries found with tibial shaft fractures were lung (12.52%) and intracranial injuries (11.3%). Of the lung injuries, a majority of the subjects suffered from pneumothorax (8.19%).

In order to gauge the importance of associated injuries, a multivariate regression analysis was conducted to determine their effects on tibial shaft fracture mortality rates. Age and comorbidities have previously been linked in determining a patient’s mortality rate for inpatient orthopaedic surgeries,17 but this study focused on how associated injuries affected patient morbidity. Overall, the presence of an associated injury had the largest effect (odds ratio = 12.9) on mortality compared to age and CCI. This demonstrates the importance of associated injuries in predicting important aspects of patient outcomes. This data implies that when assessing the mortality of a trauma patient with a tibial shaft fracture, associated injuries may be more important to examine than age or CCI.

One major limitation of this study stems from the data collected by the NTDB. Since the patient data collected by the NTDB comes from hospitals that “have shown a commitment to monitoring and improving the care of injured patients” and voluntarily submit data to the NTDB, this data may not be representative of all hospitals and trauma centers.12 Further, specific fracture and associated injury information was limited to ICD-9 level coding.

5. Conclusion

The current study evaluated and characterized a very large cohort of 27,706 patients sustaining tibial shaft fractures. The age distributions, patient characteristics, MOI, ISS, and associated injuries were defined. In total, 58.2% of patients had an associated bony fracture and 16.7% of patients had an associated internal organ injury. The importance of such associated injuries was underscored by the fact that mortality was more associated with associated injuries than patient age or comorbidities.

Conflict of interest

None.

IRB approval

A waiver was issued for this study by our institution’s Human Investigations Committee.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article. Each author certifies that he or she has not received grant support or funding for this research, and that he or she does not have any proprietary interests related to this article.

References

- 1.Larsen P., Elsoe R., Hansen S.H., Graven-Nielsen T., Laessoe U., Rasmussen S. Incidence and epidemiology of tibial shaft fractures. Injury. 2015;46(4):746–750. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2014.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waddell J.P., Reardon G.P. Complications of tibial shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;(178):173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Court-Brown C.M., Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: a review. Injury. 2006;37(8):691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonafede M., Espindle D., Bower A.G. The direct and indirect costs of long bone fractures in a working age US population. J Med Econ. 2013;16(1):169–178. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.737391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Court-Brown C.M., McBirnie J. The epidemiology of tibial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77(3):417–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worsham J.R., Elliott M.R., Harris A.M. Open calcaneus fractures and associated injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(1):68–71. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taitsman L.A., Nork S.E., Coles C.P., Barei D.P., Agel J. Open clavicle fractures and associated injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):396–399. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boraiah S., Gardner M.J., Helfet D.L., Lorich D.G. High association of posterior malleolus fractures with spiral distal tibial fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(7):1692–1698. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0224-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Y.H., Liu P.C., Chien S.H., Chou P.H., Lu C.C. Isolated posterior cruciate ligament injuries associated with closed tibial shaft fractures: a report of two cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(7):895–899. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0730-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung K.J., Chung C.Y., Park M.S. Concomitant ankle injuries associated with tibial shaft fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(10):1209–1214. doi: 10.1177/1071100715588381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuermer E.K., Stuermer K.M. Tibial shaft fracture and ankle joint injury. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22(2):107–112. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31816080bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surgeons ACo . American College of Surgeons; Chicago, IL: 2013. National Trauma Data Bank Research Data Set Admission Year 2012 user manual. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Hoore W., Bouckaert A., Tilquin C. Practical considerations on the use of the Charlson comorbidity index with administrative data bases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1429–1433. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samuel A.M., Grant R.A., Bohl D.D. Delayed surgery after acute traumatic central cord syndrome is associated with reduced mortality. Spine (Phila, PA 1976) 2015;40(5):349–356. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linn S. The injury severity score—importance and uses. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5(6):440–446. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharyya T., Iorio R., Healy W.L. Rate of and risk factors for acute inpatient mortality after orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-a(4):562–572. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]