Abstract

A series of new coumarin containing compounds were synthesized from 4-bromomethylcoumarin derivatives 2a, b and different heteroaromatic systems 4a-e, 6a-d, 8, 10via methylene thiolinker. Twenty-four compounds were screened biologically against two human tumor cell lines, breast carcinoma MCF-7 and hepatocellular carcinoma HePG-2, at the national cancer institute, Cairo, Egypt using 5-fluorouracil as standard drug. Compounds 5h, 7d, 7h, 9a, 13a and 13d showed strong activity against both MCF-7 and HepG-2 cell lines with being compound 13a is the most active with IC50 values of 5.5 µg/ml and 6.9 µg/ml respectively. Docking was performed with protein 1KE9 to study the binding mode of the designed compounds.

Keywords: Coumarin, Triazole, Oxadiazole, Thiadiazole, Anticancer

1. Introduction

Uncontrolled cellular proliferation, mediated by dysregulation of the cell-cycle machinery and activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) to promote cell-cycle progression, lies at the heart of cancer as a pathological process (O'Leary et al., 2016)

CDKs are key regulatory kinases of the cell cycle (Morgan, 1997). They regulate different phases of cell cycle by binding to distinct regulatory subunit called a cyclin (Abdel Latif et al., 2016). The importance of CDKs in cell division process directed the attention of the medicinal chemists towards the use of them as a potential targets in the treatment of human cancer (Meijer et al., 1999).

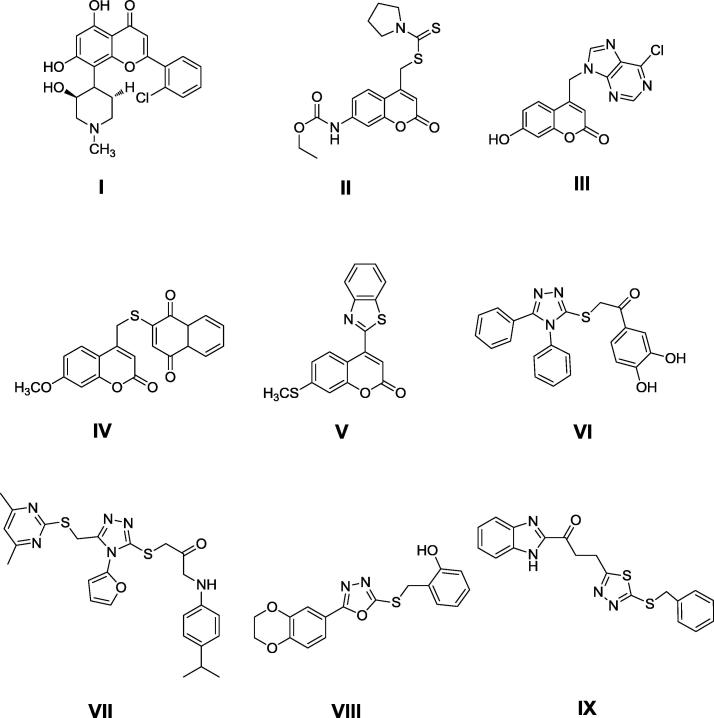

Many molecules were found to be CDK specific ATP-competitive inhibitors and few of them have progressed into human clinical trials as flavopiridol compound I (Fig. 1) which is a coumarin derivative (Senderowicz et al., 1998, Sedlacek et al., 1996).

Fig. 1.

Structures of anticancer active agents (I-IX).

Coumarins are bioactive compounds of both nature and synthetic origin and there has been a growing interest in their synthesis due to their useful and diverse pharmaceutical and biological activities (Salem et al., 2016).

Several heterocyclic compounds containing coumarin ring are associated with diverse pharmacological properties as anti-inflammatory (El-Haggar and Al-Wabli, 2015), antimicrobial (Shi and Zhou, 2011), antiviral (Tsay et al., 2013) and antitumor (Leonetti et al., 2004, Seidel et al., 2014, Jacquot et al., 2007). Moreover, coumarins bearing substitution at 4-position are known to exhibit different biological activities including antiproliferative activity against liver carcinomas ex. compound II (Neelgundmath et al., 2015) and compound III (Benci et al., 2012) and breast carcinoma as compound IV (Bana et al., 2015) and compound V (Kini et al., 2012) (Fig. 1). Coumarin itself also exhibited cytotoxic effects against Hep2 cells (human epithelial type 2) in a dose dependent manner and showed some typical characteristics of apoptosis with loss of membrane microvilli, cytoplasmic hypervacualization and nuclear fragmentation (Mirunalini et al., 2014).

Many compounds bearing five-membered heterocyclic rings in their structure have an extensive spectrum of pharmacological activities, among them 1,2,4-triazole,compound VI (Park et al., 2009) and VII (Reddy et al., 2014),1,3,4-oxadiazole,compound VIII (Zhang et al., 2011) and 1,3,4-thiadiazole,compound IX (Rashid et al., 2015) have attracted considerable interest as they all showed anticancer activity against various cancer cell lines (Fig. 1).

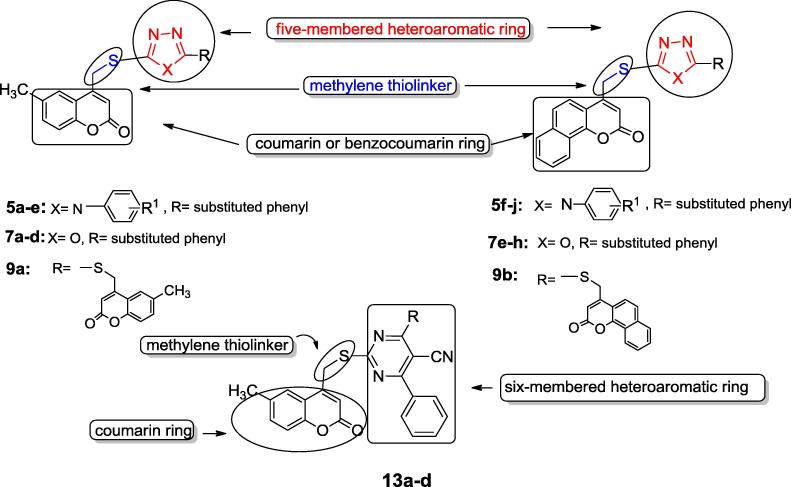

Based on the previous information we designed and synthesized a series of new coumarin containing compounds where the coumarin ring is substituted at position 4 with different five and six member heterocycles via a methylene thiolinker to test the anticancer effect of these new structure combinations against MCF-7 and HepG-2 cell lines (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Structure of the designed target compounds (5a-j, 7a-h, 9a,b and 13a-d).

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

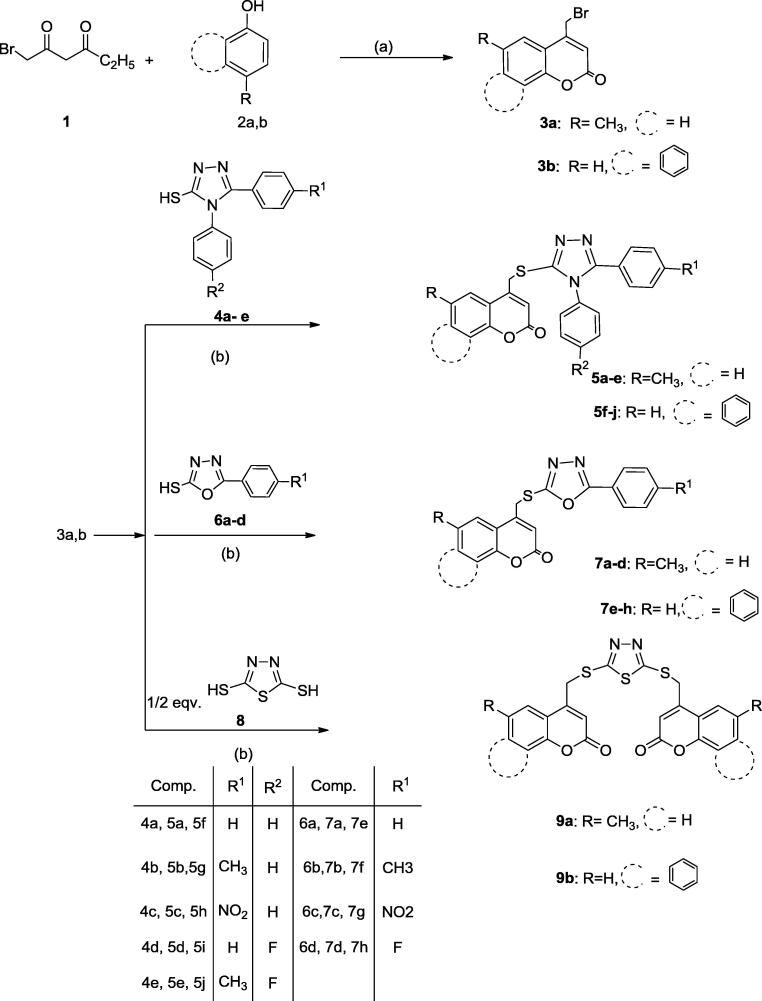

Scheme 1 illustrates the synthesis of the final compounds 5a-j, 7a-h, 9a, b. Ethyl 4-bromoacetoacetate 1 was obtained via bromination of ethyl acetoacetate using molecular bromine in ether at room temperature (Sousa et al., 2012). This bromo compound was allowed to go through Pechmann condensation with the phenol derivatives 2a, b in concentrated sulfuric acid to afford the intermediates 4-bromomethylcoumarin derivatives 3a, b (Khan et al., 2012, Basanagouda et al., 2014). The triazole derivatives 4a-e (Kusmeierza et al., 2014, Malbec et al., 1984, Sandstrom and Wennerbeck, 1966) and oxadiazole derivatives 6a-d (Charistos et al., 1994) were synthesized using the appropriate substituted phenyl hydrazide and phenylisothiocyanate or carbon disulfide, respectively while compound 8 (Kashtoh et al., 2014) was prepared applying the same procedure using hydrazine hydrate and carbon disulfide. The final compounds 5a-j, 7a-h, 9a, b were obtained in good yield after the reaction of the 4-bromomethylcoumarin derivatives 3a, b with various thiol containing heteroaromatics 4a-e, 6a-d and 8 in acetone utilizing potassium carbonate as a base

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) H2SO4. 0 °C, (b) K2CO3, Acetone, r.t.

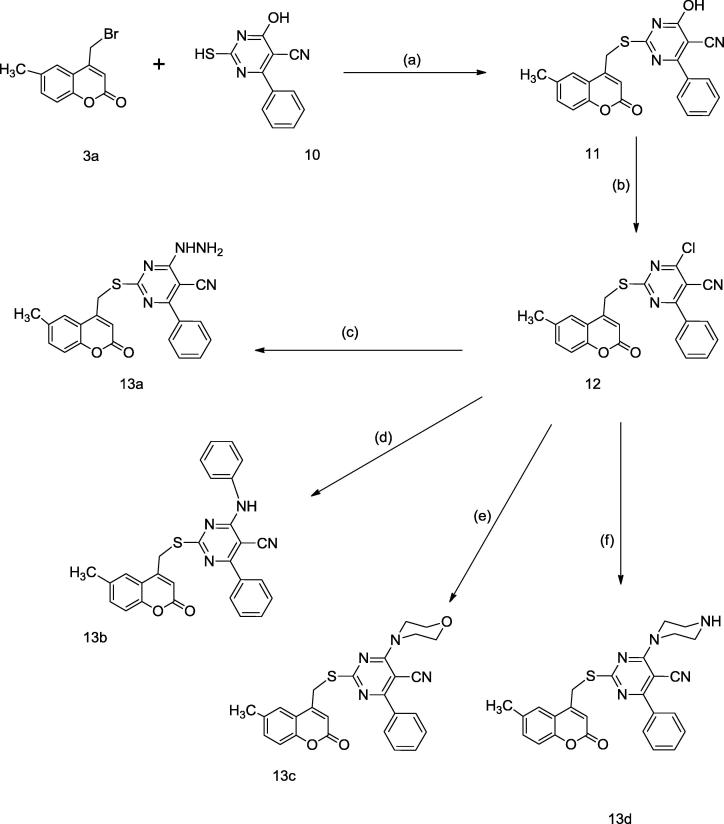

The synthesis of different pyrimidine-5-carbonitril derivatives 13a-d was described in Scheme 2. The first part of this scheme involved the preparation of the pyrimidine thiol 10 through condensation of benzaldehyde with thiourea and ethyl cyanoacetate according to the reported procedure (Shaquiquzzaman et al., 2012). Alkylation of compound 10 with the bromomethylcoumarin derivative 3a in tetrahydrofuran using triethylamine as a base afforded the intermediate alkylsulfanyl pyrimidine carbonitrile 11, which was subsequently halogenated by the reaction with phosphorous oxychloride to give the reactive chloro intermediate 12. The chloro group in compound 12 was replaced with different aliphatic and aromatic amines in ethanol to afford the final compounds 13a-d in good yield.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) THF, TEA, r.t., (b) POCl3, reflux, (c) NH2NH2, EtOH, r.t., (d) Aniline, EtOH, TEA, reflux. (e) Morpholine, EtOH, K2CO3, reflux. (f) Piperazine, EtOH, K2CO3, reflux.

2.2. Antitumor activity

Twenty-four newly synthesized compounds were tested for their cytotoxic activity against human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG-2) using MTT assay according to the method of Mosmann (Mosmann, 1983). The results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cytotoxic activity against two human tumor cell lines.

| Compounds |

In vitro Cytotoxicity IC50 (µg/ml) |

|

|---|---|---|

| HePG-2 | MCF-7 | |

| 5-FU | 7.9 ± 0.17 | 5.4 ± 0.20 |

| 5a | 32.7 ± 2.84 | 47.7 ± 2.89 |

| 5b | 57.9 ± 3.87 | 63.5 ± 4.23 |

| 5c | 26.9 ± 2.11 | 22.1 ± 1.84 |

| 5d | 62.8 ± 4.26 | 69.2 ± 4.56 |

| 5e | 41.5 ± 3.02 | 29.7 ± 1.95 |

| 5f | 20.3 ± 1.89 | 13.2 ± 1.12 |

| 5g | 96.4 ± 5.40 | 83.8 ± 5.12 |

| 5h | 12.5 ± 0.97 | 9.0 ± 0.81 |

| 5i | 45.2 ± 3.28 | 40.5 ± 2.46 |

| 5j | 76.9 ± 4.82 | 58.7 ± 3.72 |

| 7a | 100< | 100< |

| 7b | 58.1 ± 4.13 | 21.1 ± 1.63 |

| 7c | 67.7 ± 4.32 | 39.7 ± 2.54 |

| 7d | 13.6 ± 1.06 | 16.0 ± 1.38 |

| 7e | 31.1 ± 2.45 | 33.6 ± 2.37 |

| 7f | 73.0 ± 4.71 | 51.0 ± 3.45 |

| 7g | 84.4 ± 4.96 | 81.5 ± 4.95 |

| 7h | 18.2 ± 1.57 | 19.8 ± 1.40 |

| 9a | 8.3 ± 0.25 | 7.7 ± 0.56 |

| 9b | 86.0 ± 5.15 | 77.9 ± 4.81 |

| 13a | 5.5 ± 0.19 | 6.9 ± 0.38 |

| 13b | 52.0 ± 3.55 | 49.0 ± 3.10 |

| 13c | 91.1 ± 5.27 | 100< |

| 13d | 15.8 ± 1.23 | 10.9 ± 0.97 |

5-FU = 5-fluorouracil.

A series of 6-methyl-4-substituted coumarin and 4-substituted benzocoumarine was synthesized and evaluated in vitro for antitumor activity against MCF-7 and HepG-2 cell line. From the recorded IC50values in Table 1, it was observed that compounds 5h, 7d, 7h, 9a, 13a and 13d showed strong activity against both MCF-7 and HepG-2 cell line with being compound 13a is the most active comparable to 5-Fluorouracil. Compounds 5a, 5c, 5e, 5f, 5i and 7e showed moderate activity against both MCF-7 and HepG-2 cell lines. Compounds 7b and 7c showed moderate activity against MCF-7 and weak activity against HepG-2 cell line. Compounds 5b, 5j, 5g, 7f, 7g, 9b, 13b and 13c showed weak activity against both MCF-7 and HepG-2 cell lines.

From the above data we conclude that the substitution of the nitro group of 5h alters the activity either with methyl group leads to almost inactive compound 5g, 5j, while replacing it with hydrogen decreases the activity as in compounds 5f and 5i. Moreover replacing the benzocoumarine ring of 5h with methylcoumarine ring reduces the activity as in compound 5c. Moving to the oxadiazole series 7a-7h we realized that having fluorine substituted phenyl ring attached to the oxadiazole moiety leads to the most active compounds in these series either with methylcoumarine moiety attached to the oxadiazole ring 7d or with benzocoumarine ring attached to the oxadiazole ring 7h. Replacing this fluorine atom in this series with any other substituents either reduce (7b, 7c, and 7e) or kills the activity (7a, 7f and 7g). Having disubstituted thiadiazole with methylcoumarine compound gives strong active compound 9a, while replacing these two methylcoumarine rings with benzocoumarine ones leads to inactive compound 9b.

The replacement of the hydrazinyl moiety or the piperazinyl one on the pyrimidine ring in 13a and 13d by aniline in 13b or morpholine in 13c respectively resulted in reducing or killing the activity concluding that the most active compound should bear a hydrogen bond donor moiety like in 13 a, 13d.

2.3. Molecular docking

Molecular docking is a computational procedure performed on structure-based rational drug design to identify correct conformations of small molecule ligands and also to estimate the strength of the protein-ligand interaction, usually one receptor and one ligand. Docking of ligands that are bound to a receptor through non-covalent interactions is relatively conventional nowadays. The majority of docking methods development research has been focused on the effective prediction of the binding modes of non-covalent inhibitors (Kumalo et al., 2015).

CDKs have a critical role in the control of cell division so deregulation of CDKs can lead to abnormal processes and numerous human diseases, most notably cancer and tumors. Therefore, suppression of CDKs activity serves as an ideal therapeutic strategy for cancer and tumor by interrupting aberrant cell proliferation (Lu et al., 2016). A new class of drugs, termed CDK inhibitors, has been studied in preclinical and now clinical trials. These inhibitors are believed to act as an anti-cancer drug by blocking CDKs to block the uncontrolled cellular proliferation that is hallmark of cancers (Balakrishnan et al., 2016)

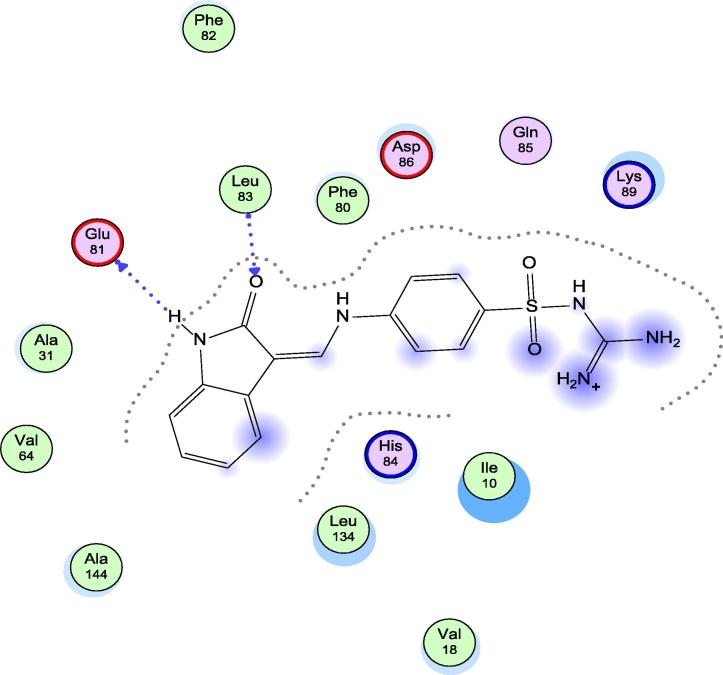

Docking Studies for the target compounds 5h, 9a and 13a, which showed the highest in vitro activity, were carried out using the molecular operating environment (MOE) to show their binding mode and suggest the proposed mechanism of their antiproliferative activity. Crystallographic structure of cyclin dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) was obtained from the protein data bank (code, 1KE9.pdb) (Bramson et al., 2001) with the help of Pharm Mapper software (Liu et al., 2010). Upon inspection of the protein embedded ligand interaction for the protein molecule 1KE9, it was found that the embedded ligand occupied the ATP-binding site of CDK2 with the formation of two hydrogen bonds, one with the backbone NH of Leu-83 and the other with the backbone carbonyl of Glu-81 as shown in (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Binding mode of the embedded ligand within 1KE9 active site.

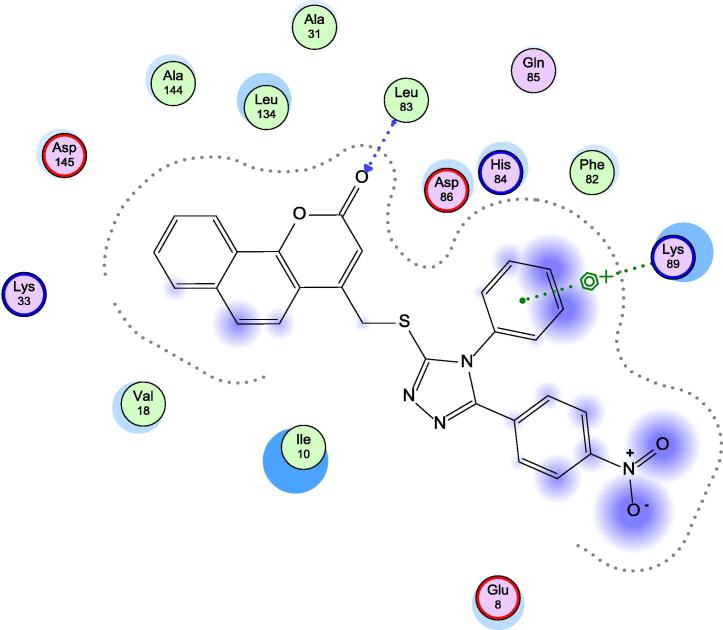

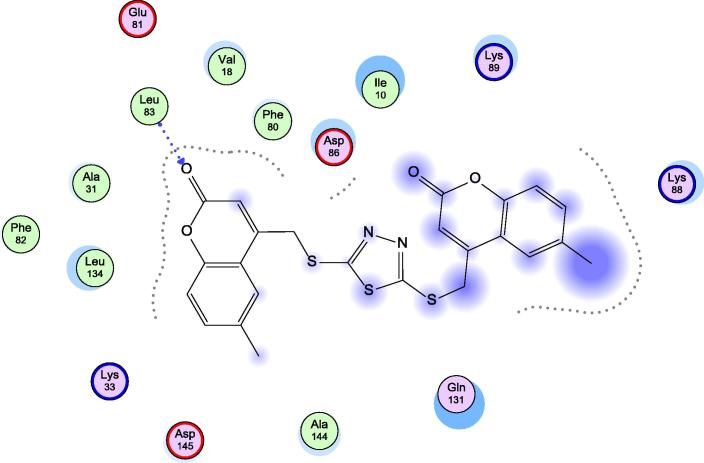

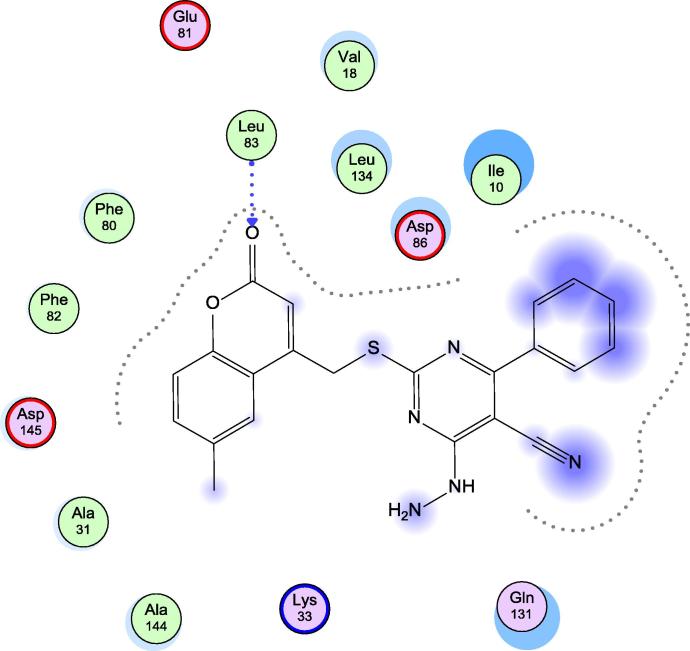

When examining the interaction between the protein and our target compounds, it was found that the target compounds occupied the same pocket of the active site of the protein and formed one hydrogen bond with backbone NH of Leu-83 as shown in (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6). These interactions assume the importance of Leu-83 residue for the activity. Also it was observed that compound 5h showed an additional binding to Lys-89 through arene cation interaction, but this interaction does not seem to have any relation to activity.

Fig. 4.

Docking of 5h in 1KE9 active site.

Fig. 5.

Docking of 9a in 1KE9 active site.

Fig. 6.

Docking of 13a in 1KE9 active site.

3. Conclusion

The target compounds showed good fit within the active site of the docked CDK2. There is a strong correlation between molecular modeling and biological screening results and it is expected that the target compounds antiproliferative activity may be due to inhibition of CDK2 activity.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

All commercial reagents were used without purification. Melting points were determined on a Mel-Temp 3.0 melting point apparatus, and are uncorrected. TLC analysis was carried out on silica gel 60 F254 precoated aluminum sheets using UV light for detection. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer and Bruker 100 MHz spectrometer, respectively using the indicated solvents. Mass spectra were obtained from the Cairo University Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Cairo, Egypt. Elemental analysis was performed at the Microanalysis Centre, Cairo University.

4.1.1. Synthesis of ethyl 4-bromoacetoacetate (1)

The required ethyl 4-bromoacetoacetate was synthesized by bromination of ethyl acetoacetate with molecular bromine in dry ether according to the published method (Sousa et al., 2012).

4.1.2. Synthesis of 4-(bromomethyl)-6-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one (3a)

It was synthesized according to the procedure described by (Khan et al., 2012).

4.1.3. Synthesis of 4-(bromomethyl)-2H-naphtho[1, 2-b]pyran-2-one (3b)

It was synthesized using known procedure (Basanagouda et al., 2014).

4.1.4. General procedure for the preparation of compounds (4a-c and 6a-d)

The required 4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol derivatives (4a-c) was synthesized according to the published procedure (Sandstrom and Wennerbeck, 1966) while 1,3,4-oxadiazole-2-thiol derivatives (6a-c) was synthesized using the known procedure (Charistos et al., 1994).

4.1.5. General procedure for the preparation of compounds (4d-e)

Potassium hydroxide solution (1.4 gm, 0.025 mol) in ethanol (100 ml) was added to the appropriate benzohydrazide (0.025 mol) under stirring. After a few minutes 4-fluorophenylisothiocyanate (3.82 gm, 0.025 mol) was added and the mixture was refluxed for 8 h. The solvent was concentrated under reduced pressure. Ice water was added to the residue and acidified by hydrochloric acid to give white solid which was filtered off, dried and recrystallized from a mixture of ethanol-water (1:1).

4.1.6. 4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol (4d)

White solid, yield 75%, m p 186–188 °C: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 7.25–7.39 (m, 5H), 7.40–7.70 (m, 4H), 10.60 (s, 1H, D2O-exchangeable); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C14H10FN3S: 271.1, found: 272.5 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C14H10FN3S: C, 61.98; H, 3.72; N, 15.49. Found: C, 62.12; H, 3.54; N, 15.65.

4.1.7. 4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(4-methylphenyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol (4e)

White solid, yield 78%, m p 222–224 °C: 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.27 (s, 3H), 7.15–7.21 (m, 4H), 7.31–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.41–7.44 (m, 2H), 10.57 (s, 1H, D2O-exchangeable); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C15H12FN3S: 285.1, found: 286.5 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C15H12FN3S: C, 63.14; H, 4.24; N, 14.73. Found: C, 63.22; H, 3.35; N, 14.55.

4.1.8. General procedure for the preparation of compounds (5a-j and 7a-h)

A mixture of 4a-e or 6a-d (0.005 mol) and anhydrous potassium carbonate (0.69 gm, 0.005 mol) was stirred for 0.5 h in dry acetone (10 ml). 3a or 3b (0.005 mol) was added to the reaction mixture and the stirring was continued for 24 h at room temperature. Ice (10 gm) was added to the reaction mixture and the separated solid was filtered then recrystallized from acetone.

4.1.9. 4-{[(4,5-Diphenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)sulfanyl]methyl}-6-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one (5a)

Brownish white solid, Yield (1.69 gm, 80%), mp 166–168 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.35 (s, 3H), 4.56 (s, 2H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 7.29–7.38 (m, 8H), 7.43–7.48 (m, 4H), 7.63 (s, 1H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C25H20N3O2S: 425.1, found: 426 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C25H20N3O2S: C, 70.57; H, 4.50; N, 9.88. Found: C, 70.73; H, 4.69; N, 9.75.

4.1.10. 6-Methyl-4-({[4-phenyl-5-(4-methylphenyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl]sulfanyl}methyl)-2H-chromen-2-one (5b)

Brownish white solid, Yield (1.79 gm, 82%), mp 183–185 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.26 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 4.45(s, 2H), 6.49(s, 1H), 7.14–7.28(m, 7H), 7.46(br s, 4H), 7.62 (s, 1H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C26H22N3O2S: 439.1, found:440 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C26H22N3O2S: C, 71.05; H, 4.82; N, 9.56. Found: C, 71.25; H, 5.00; N, 9.34.

4.1.11. 6-Methyl-4-({[5-(4-nitrophenyl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl]thio}sulfanyl)-2H-chromen-2-one (5c)

Brownish yellow solid, Yield (1.66 gm, 71%), mp 190–192 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.35 (s, 3H), 4.61 (s, 2H), 6.53 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.65 (m, 10H), 8.19 (br s, 2H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C25H19N4O4S: 470.1, found: 471.95 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C25H19N4O4S: C, 63.82; H, 3.86; N, 11.91. Found: C, 63.68; H, 3.96; N, 11.77.

4.1.12. 4-({[4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(phenyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl]sulfanyl} methyl)-6-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one (5d)

White solid, Yield (1.66 gm, 75%) mp 184–186 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.35 (s, 3H), 4.56 (s, 2H), 6.50 (s, 1H), 7.34 (br s, 8H), 7.47 (br s, 3H), 7.63 (s, 1H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C25H19FN3O2S: 443.1, found: 444.98 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C25H19 FN3O2S: C, 67.71; H, 4.09; N, 9.47. Found: C, 67.84; H, 4.27; N, 9.23.

4.1.13. 4-({[4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(4-methylphenyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl] sulfanyl}methyl)-6-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one (5e)

White solid, Yield (1.78 gm, 78%), mp 198–200 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.27 (s, 3H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 4.52 (s, 2H), 6.48 (s,1H), 7.03–7.26 (m, 5H), 7.27–7.33 (br s, 2H), 7.34–7.42 (br s, 2H), 7.43–7.44 (m, 1H), 7.62 (s, 1H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C26H21FN3O2S: 457.1, found: 458 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C26H21FN3O2S: C, 68.25; H, 4.41; N, 9.18. Found: C, 68.34; H, 4.23; N, 9.03.

4.1.14. 4-{[(4,5-Diphenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)sulfanyl]methyl}-2H-benzo [h]-2-one (5f)

White solid, Yield (1.70 gm, 74%), mp 160–162 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 4.66 (s, 2H), 6.61 (s, 1H0, 7.34 (br s, 4H), 7.39 (br s, 4H), 7.73 (br s, 4H), 7.83 (br s, 2H), 8.03–8.05 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz), 8.36–8.38 (d, 1H, J = 6);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C28H20N3O2S: 461.1, found: 462 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C28H20N3O2S: C, 72.87; H, 4.15; N, 9.10. Found: C, 72.71; H, 4.24; N, 9.25.

4.1.15. 4-({[5-(4-Methylphenyl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl]sulfanyl} methyl)-2H-benzo[h]chromen-2-one (5g)

White solid, Yield (1.80 gm, 76%), mp 180–182 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ:2.27 (s, 3H), 4.65 (s, 2H), 6.58 (s, 1H), 7.12–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.27 (m, 4H), 7.39–7.40 (m, 3H), 7.71–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.80 (brs, 2H), 8.02–8.04 (m, 1H), 8.37–8.40 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.6, 32.8, 119.4, 120.4, 122.6, 123.2, 123.9, 124.1, 124.6, 126.7, 126.8, 127.1, 127.4, 127.7, 128.6, 129.0, 129.1, 129.8, 131.9, 134.9, 142.5, 149.5, 149.6, 151.3, 160.1; ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C29H22N3O2S: 475.1,found: 475.95 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C29H22N3O2S: C, 73.24; H, 4.45; N, 8.84. Found: C, 73.05; H, 4.71; N, 8.61.

4.1.16. 4-({[5-(4-Nitrophenyl)-4-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl]sulfanyl} methyl)-2H-benzo[h]chromen-2-one (5h)

Brownish yellow solid, Yield (1.87 gm, 74%), mp 171–173 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ 4.71 (s, 2H), 6.65 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.48 (m, 7H), 7.59 (br s, 2H), 7.72 (br s, 1H), 7.84 (br s, 2H), 8.18 (br s, 2H), 8.30 (br s, 1H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C28H19N4O4S: 506.1, found: 507.90 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C28H19N4O4S: C, 66.39; H, 3.58; N, 11.06. Found: C, 66.46; H, 3.32; N, 11.25.

4.1.17. 4-({[4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-phenyl-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl]sulfanyl} methyl)-2H-benzo[h]chromen-2-one (5i)

Greyish white solid, Yield (1.62 gm, 68%), mp 194–196 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 4.64 (s, 2H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 7.20–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.35–7.40 (m, 6H), 7.72–7.73 (br s, 3H), 7.83 (br s, 2H), 8.03–8.04 (br s, 1H), 8.35–8.37 (br s, 1H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C28H19FN3O2S: 479.1, found: 480 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C28H19FN3O2S: C, 70.13; H, 3.78; N, 8.76. Found: C, 70.02; H, 4.01; N, 8.83.

4.1.18. 4-({[4-(4-Fluorophenyl)-5-(4-methylphenyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl]sulfanyl}methyl)-2H-benzo[h]chromen-2-one (5j)

Yellow solid, Yield (1.72 gm, 70%), mp 139–141 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ:2.26 (s, 3H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 6.59 (s, 1H), 7.15–7.17 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.23 (m, 4H), 7.37–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.72–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.83 (br s, 2H), 8.03–8.05 (d, 1H, J = 7 Hz), 8.36–8.37 (d,1H, J = 6 Hz); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C29H21FN3O2S: 493.1, found: 494 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C29H21FN3O2S: C, 70.57; H, 4.08; N, 8.51. Found: C, 70.61; H, 3.93; N, 8.59.

4.1.19. 6-Methyl-4-{[(5-phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)sulfanyl]methyl}-2H-chromen-2-one (7a)

Greyish white solid, Yield (1.33 gm, 76%), mp 150–152 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.38 (s, 3H), 4.77 (s, 2H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 7.12–7.53 (m, 4H), 7.80 (br s, 1H), 7.82 (br s, 2H), 7.94 (s, 1H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C19H15N2O3S: 350.1, found: 351 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C19H15N2O3S: C, 65.13; H, 4.03; N, 7.99. Found: C, 65.21; H, 4.10; N, 7.84.

4.1.20. 6-Methyl-4-({[(5-methylphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]sulfanyl}methyl) -2H-chromen-2-one (7b)

Brownish white solid, Yield (1.43 gm, 79%), mp 174–176 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ:2.39 (s, 6H), 4.70 (s, 2H), 6.60 (s, 1H), 7.39–7.46 (m, 4H), 7.83 (br s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.0, 21.6, 32.3, 116.4, 117.3, 117.5, 120.5, 123.8, 126.7, 129.8, 133.3, 142.5, 148.5, 152.0, 160.6, 161.98, 166.6; ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C20H17N2O3S: 364.1, found: 365.97 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C20H17N2O3S: C, 65.92; H, 4.43; N, 7.69. Found: C, 65.99; H, 4.37; N, 7.72.

4.1.21. 6-Methyl-4-({[5-(4-nitrophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]sulfantl}methyl) -2H-chromen-2-one (7c)

Brownish yellow solid, Yield (1.38 gm, 70%) mp 190–192 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ:2.39(s, 3H),4.82(s, 2H), 6.64 (s,1H), 7.33 (br s,1H), 7.46 (br s,1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 8.21 (br s, 2H), 8.38 (br s, 2H);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C19H14N3O5S: 395.1, found: 396.90 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C19H14N3O5S: C, 57.72; H, 3.31; N, 10.63. Found: C, 57.61; H, 3.39; N, 10.54.

4.1.22. 4-({[5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]sulfanyl}methyl)-6-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one (7d)

Grey solid, Yield (1.28 gm, 70%), mp 141–143 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.39 (s,3H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 6.64 (s,1H), 7.33 (bs,1H), 7.46 (bs, 1H), 7.84 (s, 1H), 8.20 (bs, 2H), 8.39 (bs, 2H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C19H14N3O5S: 368.1, found: 369 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C19H14N3O5S: C, 61.95; H, 3.56; N, 7.60. Found: C, 61.77; H, 3.60; N, 7.74.

4.1.23. 4-{[(5-Phenyl-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl)sulfanyl]methyl}-2H-benzo[h] chromen-2-one (7e)

white solid, Yield (1.44 gm, 75%), mp 150–152 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 4.98 (s, 2H), 6.72–6.73 (br s,1H), 7.34–7.36 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.55–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.71 (br s, 2H), 7.80–7.81 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.88–7.93 (m, 2H), 8.01–8.03 (m, 2H), 8.33–8.35 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C22H15N2O3S: 386.1, found: 386.97 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C22H15N2O3S: C, 68.38; H, 3.65; N, 7.25. Found: C, 68.44; H, 3.41; N, 7.33.

4.1.24. 4-({[5-(4-Methylphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]sulfanyl}methyl)-2H-benzo[h]chromen-2-one (7f)

white solid, Yield (1.54 gm, 77%), mp 177–178 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.39 (s, 3H), 4.88 (s, 2H), 6.72 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.37 (d, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.71–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.80–7.82 (d, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 7.87–7.90 (d, 1H, J = 12.8 Hz), 7.99–8.01 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.03–8.05 (m, 1H), 8.37–8.39 (d, 1H, J = 8 Hz,); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.3, 33.3, 119.8, 122.6, 123.2, 123.3, 124.3, 127.1, 127.6, 128.0, 128.8, 129.2, 129.9, 133.8, 134.8, 140.2, 150.5, 150.7, 151.1, 155.6, 160.3; ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C23H17N2O3S: 400.1, found: 401 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C23H17N2O3S: C, 68.98; H, 4.03; N, 7.00. Found: C, 68.89; H, 4.15; N, 6.94.

4.1.25. 4-({[5-(4-Nitrophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]sulfanyl}methyl)-2H-benzo[h]chromen-2-one (7g)

Brown solid, Yield (1.50 gm, 70%), mp 200–202 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 4.94 (s, 2H), 6.78 (s, 1H), 7.63–7.80 (m, 1H), 7.94 (m, 1H), 8.06 (m, 2H), 8.19–8.21 (m, 2H), 8.37 (m, 4H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C22H14N3O5S: 431.1, found: 432.95 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C22H14N3O5S: C, 61.25; H, 3.04; N, 9.74. Found: C, 61.33; H, 2.98; N, 9.66.

4.1.26. 4-({[5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]sulfanyl}methyl)-2H-benzo[h]chromen-2-one (7h)

Yellowish white solid, Yield (1.41 gm, 70%), mp 156–158 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 4.93 (s, 2H), 6.78 (s,1H), 7.65–7.80 (m, 3H), 7.92 (m,1H), 8.02–8.05 (m, 2H), 8.20–8.26 (m, 1H), 8.30–8.39 (m, 3H);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C22H14FN2O3S:404.1, found: 405.90 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C22H14FN2O3S: C, 65.34; H, 3.24; N, 6.93. Found: C, 65.23; H, 3.29; N, 6.77.

4.1.27. Synthesis of 1,3,4-thiadiazole-2,5-dithiol (8)

Compound 8 was synthesized according to the published method (Kashtoh et al., 2014).

4.1.28. Synthesis of 4,4′-{[(1,3,4-thiadiazole-2,5-diyl)bis(sulfanediyl)]bis (methylene)}bis(6-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one)(9a)and4,4′-{[(1,3,4-thiadiazole-2,5-diyl)bis(sulfanediyl)]bis(methylene)}bis(2H-benzo[h] chromen-2-one) (9b)

A mixture of 1,3,4-thiadiazole-2,5-dithiol (8) (0.75gm, 0.005 mol) and anhydrous potassium carbonate (1.38 gm, 0.01 mol) was stirred for 1 h in dry acetone (10 ml) at room temperature. 3a or 3b(0.01 mol) was added and the stirring was continued for 24 h at room temperature. Then the resulting reaction mixture was poured into crushed ice. The separated solid was filtered, air dried and recrystallized from dimethylformamide.

4.1.29. 4,4′-{[(1,3,4-Thiadiazole-2,5-diyl)bis(sulfanediyl)]bis(methylene)}bis (6-methyl-2H-chromen-2-one) (9a)

Yellow white solid, Yield (1.5 gm, 62%), mp 131–133 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.37 (s, 6H), 4.70 (s,4H), 6.50 (s, 2H), 7.31 (br s, 2H), 7.46 (br s, 2H), 7.76 (br s, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz)δ 20.9, 34.3, 115.3, 116.9, 117.8, 125.6, 125.7, 133.4, 134.1, 151.7, 151.9, 160.1;ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C24H18N2O4S3: 494, found: 495.80 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C24H18N2O4S3: C, 58.28; H, 3.67; N, 5.66. Found: C, 58.46; H, 3.85; N, 5.36.

4.1.30. 4,4′-{[(1,3,4-Thiadiazole-2,5-diyl)bis(sulfanediyl)]bis(methylene)}bis (2H-benzo[h] chromen-2-one) (9b)

Brownish yellow solid, yield (1.8 gm, 65%), mp 198–200 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 4.90 (s, 4H), 6.56 (s, 2H), 7.65–7.76 (m, 3H), 7.83–7.93 (m, 3H), 7.94–8.10 (m, 4H), 8.20–8.50 (br s, 2H);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C30H18N2O4S3: 566, found: 567 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C30H18N2O4S3: C, 63.59; H, 3.20; N, 4.94. Found: C, 63.34; H, 3.39; N, 5.03.

4.1.31. Synthesis of 4-hydroxy-2-sulfanyl-6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (10)

Compound 10 was synthesized according to the published method (Shaquiquzzaman et al., 2012).

4.1.32. Synthesis of 4-hydroxy-2-{[(6-methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl]sulfanyl}-6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (11)

Triethylamine (1 ml, 0.01 mol) was added to a solution of 10 (2.29 g, 0.01 mol) in dry tetrahydrofuran. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h then solution of 3a (2.52 g, 0.01 mol) in dry tetrahydrofuran was added portionwise and the reaction mixture was stirred for additional 24 h at room temperature then the solvent was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was poured onto crushed ice with stirring. The precipitate was filtered off and recrystallized from ethanol to give compound 11.

Brownish white solid (2.44 gm, 61%), mp 240–242 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.33 (s, 3H), 4.59 (s, 2H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 7.45 (br s, 4H), 7.79 (br s, 3H), 10.05 (s, 1H, D2O-exchangable);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C22H16N3O3S: 401.1, found: 402.97 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C22H16N3O3S: C, 65.82; H, 3.77; N, 10.47. Found: C, 65.69; H, 3.67; N, 10.73.

4.1.33. Synthesis of 4-chloro-2-{[(6-methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl]sulfanyl}-6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (12)

Phosphorous oxychloride (10 ml) was added dropwise with stirring to a flask charged with compound 11 (4.4 g, 0.011 mol) at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 0.5 h then refluxed on water bath at 70 °C for 6 h. The reaction mixture was cooled, and poured onto crushed ice. The formed solid was filtered and recrystallized from methylene chloride to give compound 12.

Light brown solid, (3 gm, 65%), mp 231–233 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.37 (s, 3H), 4.76 (s, 2H), 6.62 (s, 1H), 7.34 (br s, 1H), 7.48–7.56 (m, 3H), 7.65 (br s, 1H), 7.83–7.90 (m, 3H);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C22H15ClN3O2S: 419, found: 420.96 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C22H15ClN3O2S: C, 62.93; H, 3.36; N, 10.01. Found: C, 63.12; H, 3.30; N, 10.15.

4.1.34. Synthesis of 4-substituted-2-{[(6-methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl]sulfanyl}-6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (13a and 13b)

Solution of compound 12 (2 gm, 0.005 mol) in absolute ethanol was added portionwise to a well stirred solution of the appropriate amine (0.005 mol) and triethyl amine (0.5 ml, 0.005 mol) in absolute ethanol (10 ml). The mixture was refluxed for 5 h then the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the remained solid was washed with cold water and purified by recrystallization from ethanol.

Compound 13a was prepared by stirring the reaction mixture for 8 h at room temperature and no need to reflux, then left to stand overnight at room temperature. The formed precipitate was filtered, air dried and recrystallized from ethanol.

4.1.35. 4-Hydrazinyl-2-{[(6-methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl]sulfanyl} -6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (13a)

Light brown solid, (1.49 gm, 72%), mp 207–209 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.34 (s, 3H), 4.68 (s, 2H), 5.10 (s, 2H, D2O exchangeable) 6.65 (s, 1H), 7.32 (br s, 1H), 7.48–7.53 (m, 4H), 7.76 (br s, 3H), 9.80(s, 1H, D2O-exchangeable);ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C22H18N5O2S: 415.1, found: 416.95 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C22H18N5O2S: C, 63.60; H, 4.12; N, 16.86. Found: C, 63.79; H, 4.03; N, 16.80.

4.1.36. 2-{[(6-Methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl]sulfanyl}-4-Phenylamino-6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (13b)

Brownish yellow solid, (1.7 gm, 72%), mp 287–289 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ:2.35 (s, 3H), 4.50 (s, 2H), 6.24 (s, 1H), 7.04–7.31 (m, 4H), 7.45–7.56 (m, 7H), 7.85 (br s, 2H) 9.95(s, 1H, D2O-exchangeable); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C28H21N4O2S: 476.1, found: 477 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C28H21N4O2S: C, 70.57; H, 4.23; N, 11.76. Found: C, 70.43; H, 4.15; N, 11.84.

4.1.37. Synthesis of 4-substituted-2-{[(6-methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl) methyl]sulfanyl}-6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (13c and 13d)

A mixture of morpholine (0.8 gm, 0.01 mol) or piperazine (5.16 gm, 0.06 mol) and anhydrous potassium carbonate (1.38 gm, 0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (8 ml) was stirred for 0.5 h. A solution of compound 12 (4.19 gm, 0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (12 ml) was added portionwise. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 8 h, allowed to cool then filtered. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure then poured onto crushed ice. The formed precipitate was filtered, washed with water and recrystallized from water/acetone.

Compound 13d was prepared using the same procedure but the filtrate was stirred with 2N hydrochloric acid before filtration,

4.1.38. 2-{[(6-Methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl]sulfanyl}-4-(morpholin -4-yl)-6-phenylpyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (13c)

Yellowish orange solid, (2.8 gm, 60%), m p 220–222 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.37 (s, 3H), 3.60 (br s, 4H), 3.84 (br s, 4H) 4.66 (s, 2H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 7.36 (br s, 2H), 7.40–7.65 (m, 3H), 7.80(br s, 3H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C26H23N4O3S: 470.1, found: 471.97 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C26H23N4O3S: C, 66.37; H, 4.71; N, 11.91. Found: C, 66.44; H, 4.58; N, 11.98.

4.1.39. 2-{[(6-Methyl-2-oxo-2H-chromen-4-yl)methyl]sulfanyl}-4-phenyl-6-(piprazinyl-1-yl)pyrimidine-5-carbonitrile (13d)

Light orange solid, (2.5 gm, 53%), mp 215–217 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ: 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.82 (br s, 4H), 3.82 (br s, 4H), 4.65 (s, 2H), 6.57 (s, 1H), 7.35 (m, 1H), 7.47–7.58 (m, 4H), 7.73 (br s, 1H, D2O exchangeable), 7.81 (br s, 3H); ESI-MS: m/z calculated for C26H24N5O2S: 469.2, found: 470 (M++1); Anal. Calcd. For C26H24N5O2S: C, 66.50; H, 4.94; N, 14.91. Found: C, 66.41; H, 4.87; N, 15.11.

4.2. Biology

All final compounds were evaluated for their antitumor activity against human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG-2) adopting MTT assay [1]. All materials were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co (USA). The cell lines were obtained from ATCC via Holding company for biological products and vaccines (VACSERA), Cairo, Egypt. 5-Fluorouracil was used as a standard anticancer drug for comparison. MTT assay is a colorimetric assay based on the reduction of the 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) to a purple formazan derivative by mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase in viable cells. Cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Antibiotics added were 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. The cell lines were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well at 37 °C for 48 h under 5% CO2. After incubation the cells were treated with different concentration of the tested compounds and incubated for 24 h, then 20 µl of MTT solution at 5 mg/ml was added and incubated for 4 h. 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is added into each well to dissolve the purple formazan formed. The absorbance of each well was measured by a microplate reader (EXL 800 USA) using a test wavelength of 570 nm. The results was expressed as IC50, which is the concentration of the drugs inducing a 50% inhibition of cell growth of treated cells when compared to the growth of control cells. The IC50 values were calculated using different concentrations of the tested compounds (Mosmann, 1983).

4.3. Molecular docking

The docking studies and modeling calculations were done using ‘MOE version 2009.10 release of Chemical Computing Group’s’ which was operated under Windows XP operating system installed on an Intel Pentium IV PC with a 2.8 MHz processor and 512 RAM. The tested compounds were built in 2D using ChemBiooffice suite and geometric optimization was done using Hyperchem, then subjected to docking simulation. The X-ray crystallographic structure of CDK2 protein enzyme was obtained from the Protein Data Bank; code ‘1KE9.pdb’.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Dr. Laila A. Abou-zeid, and Dr. Shahenda El messery, pharm. Organic chemistry Dept. Faculty of Pharmacy, Mansoura University, for their helpful discussions in molecular modeling.

Also, the authors would thank the Faculty of pharmacy, Mansoura University for using its laboratory equipments during this work.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abdel Latif A.N., Batran R.Z., Khedr M.A., Mohamed M., Abdalla M.M. 3-Substituted-4-hydroxycoumarin as a new scaffold with potent CDK inhibition and promising anticancer effect: synthesis, molecularmodeling and QSAR studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2016;67:116–129. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan A., Vyas A., Deshpande K., Vyas D. Pharmacological cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors: implications for colorectal cancer. World J. Jastroenterol. 2016;22:2159–2164. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i7.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bana E., Sibille E., Valente S., Cerella C., Chaimbault P., Kirsch G., Dicato M., Diederich M., Bagrel D. A novel coumarin-quinone derivative SV37 inhibits CDC25 phosphatases, impairs proliferation, and induces cell death. Mol. Carcinog. 2015;54:229–241. doi: 10.1002/mc.22094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basanagouda M., Jambagi V.B., Barigidad N.N., Laxmeshwar S.S., Devaru V., Narayanachar Synthesis, structure activity relationship of iodinated-4-aryloxymethyl-coumarins as potential anti-cancer and antimycobacterial agents. Euro. J. Med. Chem. 2014;74:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benci K., Mandić L., Suhina T., Sedić M., Klobučar M., Pavelić S.K., Pavelić K., Wittine K., Mintas M. Novel Coumarin derivatives containing 1,2,4-triazole, 4,5-dicyanoimidazole and purine moieties: synthesis and evaluation of their cytostatic activity. Molecules. 2012;17:11010–11025. doi: 10.3390/molecules170911010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramson H.N., Corona J., Davis S.T., Dickerson S.H., Edelstein M., Frye S.V., Gampe R.T., Jr., Harris P.A., Hassell A., Holmes W.D., Hunter R.N., Lackey K.E., Lovejoy B., Luzzio M.J., Montana V., Rocque W.J., Rusnak D., Shewchuk L., Veal J.M., Walker D.H. Oxindole-based inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2): design, synthesis, enzymatic activities, and X-ray crystallographic analysis. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:4339–4358. doi: 10.1021/jm010117d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charistos D.A., Vagenas G.V., Tzavellas L.C., Tsoleridis C.A., Rodios N.A. Synthesis and a UV and IR spectral study of some 2-aryl-Δ-2-1,3,4-oxadiazoline-5-thiones. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1994;31:1593–1598. [Google Scholar]

- El-Haggar R., Al-Wabli R.I. Anti-inflammatory screening and molecular modeling of some novel coumarin derivatives. Molecules. 2015;20:5374–5391. doi: 10.3390/molecules20045374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquot Y., Laïos I., Cleeren A., Nonclercq D., Bermont L., Refouvelet B., Boubekeur K., Xicluna A., Leclercq G., Laurent G. Synthesis, structure, and estrogenic activity of 4-amino-3-(2-methylbenzyl) coumarins on human breast carcinoma cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:2269–2282. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashtoh H., Hussain S., Khan A., Saad S.M., Khan J.A.J., Khan K.M., Perveen S., Choudhary M.I. Oxadiazoles and thiadiazoles: novel α-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:5454–5465. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M., khan A., Ali S.A. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel coumarin derivatives. Int. J. Pharm. Innovations. 2012;2:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kini G.S., Choudhary S., Mubeen M. Synthesis, docking study and anticancer activity of coumarin substituted derivatives of benzothiazole. J. Comput. Meth. Mol. Des. 2012;2:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kumalo H.M., Bhakat S., Soliman M.E. Theory and applications of covalent docking in drug discovery: merits and pitfalls. Molecules. 2015;20:1984–2000. doi: 10.3390/molecules20021984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusmeierza E., Siweka A., Kosikowskab U., Malmb A., Plech T., Wrobelc A., Wujec M. Antimicrobial and physicochemical characterizations of thiosemicarbazide and s-triazole derivatives. Phophorous, Sulfur, Silicon Relat. Elem. 2014;189:1539–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti F., Favia A., Rao A., Aliano R., Paluszcak A., Hartmann R.W., Carotti A. Design, synthesis, and 3D QSAR of novel potent and selective aromatase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:6792–6803. doi: 10.1021/jm049535j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Ouyang S., Yu B., Huang K., Liu Y., Gong J., Zheng S., Li Z., Li H., Jiang H. PharmMapper Server: a web server forpotential drug target identification via pharmacophore mappingapproach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:609–614. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F., Luo G., Qiao L., Ludi Jiang L., Li G., Zhang Y. Virtual screening for potential allosteric inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 from traditional chinese medicine. Molecules. 2016;21:1259–1273. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malbec F., Milcent R., Barbier G. Dérivés de ladihydro-2,4 triazole-1,2,4 thione-3 et de l'amino-2 thiadiazole-1,3,4 à partir de nouvellesthiosemicarbazonesd'esters. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1984;21:1689–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer L., Leclerc S., Leost M. Properties and potential applications of chemical inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999;82:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirunalini S., Deepalakshmi K., Manimozhi J. Antiproliferative effect of coumarin by modulating oxidant/antioxidant status and inducing apoptosis in Hep2 cells. Biomed. Aging Pathol. 2014;4:131–135. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D.O. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, andmicroprocessors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelgundmath M., Dinesh K.R., Mohan C.D., Li F., Dai X., Siveen K.S., Paricharak S., Mason D.J., Fuchs J.E., Sethi G., Bender A., Rangappa K.S., Kotresh O., Basappa S. Novel synthetic coumarins that targets NF-kB in hepatocellularcarcinoma. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;25:893–897. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary B., Finn R.S., Turner N.C. Treating cancer with selective CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016;13:417–430. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Bahn Y.J., Ryu S.E. Structure-based de novo design and biochemical evaluation of novel Cdc25 phosphatase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;29:4330. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid M., Husain A., Mishra R., Karim S., Khan S., Ahmad M., Al-wabel N., Husain A., Ahmad A., Khan S.A. Design and synthesis of benzimidazoles containing substituted oxadiazole, thiadiazole and triazolo thiadiazinesas a source of new anticancer agents. Arab. J. Chem. 2015 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Reddy T.R., Li C., Guo X., Fischer P.M., Dekker L.V. Design, synthesis and SAR exploration of tri-substituted 1,2,4-triazoles as inhibitors of the annexin A2-S100A10 protein interaction. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:5378. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem M.A., Marzouk M.I., El-Kazak A.M. Synthesis and characterization of some new coumarins with in vitro antitumor and antioxidant activity and high protective effects against DNA damage. Molecules. 2016;21:249–269. doi: 10.3390/molecules21020249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom J., Wennerbeck I. Tautomeric cyclic thiones. Part II. Tautomerism, acidity and electronic spectra of thioamides of the oxadiazole, thiadiazole, and thiazole groups. Acta Chem. Scand. 1966;20:57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlacek H.H., Czech J., Naik R., Kaur G., Worland P. Flavopiridol (L868275; NSC 649890), a new kinase inhibitor fortumor therapy. Int. J. Oncol. 1996;9:1143–1168. doi: 10.3892/ijo.9.6.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel C., Schnekenburger M., Zwergel C., Gaascht F., Mai A., Dicato M., Kirsch G., Valente S., Diederich M. Novel inhibitors of human histone deacetylases: design, synthesis and bioactivity of 3-alkenoylcoumarines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014:243797–243801. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senderowicz A.M., Headlee D., Stinson S.F., Lush R.M., Kalil N. Phase I trial of continuous infusion flavopiridol, a novel cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, in patients with refractory neoplasms. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998;16:2986–2999. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaquiquzzaman M., Khan S.A., Mohammad Amir M., Alam M.M. Synthesis, anticonvulsant and neurotoxicity evaluation of some new pyrimidine-5-carbonitrile derivatives. Saudi Pharm. J. 2012;20:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Zhou C. Synthesis and evaluation of a class of new coumarin triazole derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:956–960. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa Céu M., Berthet J., Delbaere S., Coelho P.J. Photochromic fused-naphthopyrans without residual color. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:3959–3968. doi: 10.1021/jo3003216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsay S.C., Hwu J.R., Singha R., Huang W.C., Hsiung Y., Chang Hsu M.H., Shieh F.K., Lin C.C., Hwang K.C., Horng J., De Clercq E., Vliegen I., Neyts J.C. Coumarins hinged directly on benzimidazoles and their ribofuranosides to inhibit hepatitis C virus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;63:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.M., Qiu M., Sun J., Zhang Y.B., Yang Y.S., Wang X.L., Zhu H.L. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking studies of 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives possessing 1,4-benzodioxan moiety as potential anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:6518–6524. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]