Abstract

Forming conceptually rich social categories helps people navigate the complex social world by allowing them to reason about others’ likely thoughts, beliefs, actions, and interactions as guided by group membership. Yet, social categorization often has nefarious consequences. We suggest that the foundation of the human ability to form useful social categories is in place in infancy: social categories guide infants’ inferences about peoples’ shared characteristics and social relationships. We also suggest that the ability to form abstract social categories may be separable from the eventual negative downstream consequences of social categorization, including prejudice, discrimination and stereotyping. Whereas a tendency to form inductively rich social categories appears early in ontogeny, prejudice based on each particular category dimension may not be inevitable.

Keywords: essentialism, infant, intergroup cognition, prejudice, social categorization, stereotype

Social categorization profoundly influences human social life

Despite the salience of individuals in social thinking, a large body of work suggests that the tendency to conceive of people as belonging to social categories is automatic [1–3]. Indeed, the ability to group instances into categories and to use category-based knowledge to generate novel inductive inferences is a powerful aspect of human cognition [1,4]. In particular, the capacity to view category members as sharing important, unchanging, and possibly unobservable similarities allows people to efficiently, and perhaps even spontaneously, learn a property of a category and apply it to novel category members [5–9]. When applied to the social domain, forming conceptually rich categories has obvious functional value – social categories organize people’s vast knowledge about human attributes and about the complex relationship networks that comprise human social life [10].

Despite the upsides of category formation, much of the research on social categorization focuses on its potential downstream negative consequences. Social categorization differs from other forms of categorization in that people tend to place themselves in a category [11], leading them to be partial to members of their own group (ingroup) relative to those from other groups (outgroup) in terms of social preferences, empathic responding, and resource distribution [12–15]. Beyond sheer partiality and greater liking of members of one’s own group, some of the most invidious effects of social categories result from the biased belief systems that social categorization supports, including stereotypes for, essentialist beliefs about, and even dehumanization of, members of certain social groups [12–13, 16–17].

Although prejudice was once assumed to be an inevitable consequence of social categorization [12], social psychologists have long noted the distinction between explicit prejudice (negative affect towards an outgroup) and endorsement of stereotypes (cognitive representations of culturally held beliefs about a group) [1]. Whereas less research has focused on the affective-cognitive distinction in implicit cognition, implicit evaluations of social groups (implicit prejudice) may also be distinct from implicit stereotyping, and these constructs have separable influences on human social behavior [18]. Nonetheless, there are many important open questions about each of these outcomes of social categorization. For example, what is the time course of affective and categorical thinking about groups [19], and how does one influence the other? How do social categories work similarly to, and different from, non-social categories [11], and how do stereotypes about groups develop in the first place [20]?

One way to continue to answer important questions about the nature of social categorization is to look to developmental psychology. For example, research with infants and children can ask whether social preferences and inductive inferences based on social group membership always emerge together, or whether they arise separately [21]. Findings from such studies can demonstrate whether prejudice and stereotyping are inevitable consequences of dividing the world in conceptually meaningful social categories, or whether humans are able to use group divisions in meaningful ways without these negative outcomes. Here, we examine new experiments with children and infants to understand the nature and origins of the human capacity to form social categories. Considering social categories from a developmental perspective does more than merely shed light on when social categorization and its downstream consequences arise, it can also reveal the cognitive processes that shape the human ability to form social categories and provide insight into how negative consequences of social categorization begin and might be mitigated.

Social categorization in childhood

Social preferences for members of one’s own social group, and rich conceptual inferences based on social group membership are each in place by the time children enter formal schooling. For example, children have both explicit and implicit preferences based on people’s gender, race, and linguistic group [22–25]. Children also look to ingroup, rather than outgroup, members when learning new information [26–30], show partiality towards the ingroup when allocating rewards and punishments [31–32] and acquire negative stereotypes associated with social group membership [20].

Recent research indicates that children use social categories to make productive social inferences. For example, children expect members of a social group to share deep properties, including preferences, traits, and norms [33–37], and they expect characteristics that mark social category membership to endure over time [38–39]. Indeed, preschoolers expect group members to follow social conventions [40], and negatively evaluate people who do not follow their social group’s conventions and norms [41–42], suggesting they view conforming to the group as a fundamentally important feature of group membership. In addition to sharing common attributes, members of a social category are typified by rich relational structure, such that social categories support inferences about patterns of interpersonal interaction. For example, by early childhood, people expect members of a social category to be loyal to one another, to engage in prosocial relationships, and to share resources with each other [43–46]. In fact, whereas children think that people in a social group must refrain from harming one another, this expectation does not always hold between members of different social groups [45].

Although children hold intuitive theories that social categories are natural kinds and that social categories should mark social obligations [47], children apply these two intuitive theories differently to different social groups. Children treat gender as a natural kind [48], but they do not view novel groups [49–50] or race [51], as marking fundamental similarities between category members. On the other hand, children of the same age do use novel groups and race for predicting patterns of social interaction [46, 51]. Children may initially view social categories as marking social obligations, and later come to see these categories as natural kinds [47]. Or, children may prioritize the significance of some social categories as compared to others, and reason about prioritized categories as natural kinds and as marking patterns of social interactions at earlier ages (Box 1). In either case, existing data suggest that the formation of a social group in and of itself does not inherently lead to stereotyping or prejudice: children can know about a social division, such as race or novel group, without using group boundaries to make inductive inferences [46. 50], and without expressing group bias [52].

Box 1. Infants may prioritize informative social categorization signals.

Rather than varying across communities based on learning which dimensions carry the most functional relevance (Box 3), infants’ earliest social categories may prioritize features that have fundamentally signaled social group membership across human evolutionary history. A prioritization account could help explain potentially counterintuitive research on race. Because people in hunter-gather bands likely never traveled far enough to encounter someone of a different “race,” race might not be a prioritized signal of social group [101]. Indeed, although infants perceive race (Box 2) and children prefer own-race social partners [22], children do not use race as a conceptually rich category. Children do not automatically encode race [3], do not make race-based inductive inferences [46], and do not always expect race to be stable [38, 88]. Rather, seeing race as relevant for social categorization depends on social experience: minority race children, who likely think and talk more about race, see race as a defining feature of social identity earlier in development than majority race children [38, 88]. Additionally, growing up in racially diverse areas decreases children’s racial essentialism [102], and racial essentialism leads children to treat ambiguous race faces as outgroup members [103], suggesting exposure to diversity could decrease prejudice. On the other hand, gender may be a dedicated dimension of social categorization: children automatically encode gender [3], and make gender-based inductive inferences [38]. In fact, transgender children express clear gender identities and use gender to carve up the social world [104], suggesting attention to gender is present across a variety of experiences and backgrounds.

If humans’ system for reasoning about social categories is structured to attend to evolutionarily relevant groups, which features would infants prioritize? Spoken language and food preferences vary across groups, and are constrained by sensitive periods for learning ([105–108] Box 4), making them potential candidates for prioritized social categorization. Indeed, infants see shared language and shared foods preferences as providing information about social obligation and inductive generalization [76–77,80]. Critically, language and food preferences may have a special significance–infants do not use highly similar cues, such as object preferences, to make the same kinds of social inferences [80]. This account would make the further predictions (not yet tested) that infants’ social inferences would be guided by other fundamental markers of social group membership, such as kinship, or knowledge of group rituals, but not by arbitrary dimensions of similarity that did not mark social group across human evolutionary history.

The relationship between social preferences and social categorization

The growing body of research on children’s social categories brings into focus the distinction between conceptually rich belief systems about members of certain social categories (perhaps relevant to later stereotyping) and social preferences for people who are members of those categories (perhaps relevant to later prejudice). Though both develop by early school years, and they are often coincident, these two processes are not identical: they may emerge and interact in different ways over the course of development. In fact, there are many theoretical reasons to expect that social preferences could diverge from rich knowledge of social groups.

First, preferences can exist in the absence of knowledge about groups. For example, preferential looking time methodologies, which measure infants’ spontaneously looking to a pair of faces, find that infants spend more time looking at attractive compared to unattractive faces [53], native speakers compared to foreign language speakers [24], and own-race compared to other-race faces [54]. Although preferential looking time studies have been taken as evidence for an early-developing own race bias, preferential looking does not necessarily indicate categorization, or a preference for the “ingroup.”1 Indeed, few people would take longer looking at symmetrical faces as evidence that infants form a conceptual category of “attractive people” and expect attractive people to share common essentialized properties. Instead, infants may prefer individuals with symmetrical faces for a variety of reasons, including that symmetry may indicate health [55]. Indeed, infants could look longer at symmetrical faces without grouping these faces into a category at all. Similarly, even social preferences that seem more plausibly relevant to early ingroup bias, such as infants’ tendency to preferentially interact with native language speakers [24], could emerge based on liking to approach relatively more familiar social partners, without having any abstract categorization of “native speaker” or “foreign speaker,” or even of “like me” and “not like me.” Some looking time data, such as when an infant who is habituated one type of face (e.g., gender or race), subsequently looks longer at a face of someone from a different group, may be better evidence for categorization, though this categorization could nonetheless be perceptual rather than conceptual (see 21,54 and Box 2 for review of such literature).

Box 2. Do visual preferences in infancy reflect social categorization?

Infants show clear visual preferences for people from certain social groups [see 21, 54 for review]. For example, infants prefer to look at female faces [55, 109], and at own-race faces [110]. These effects are due to familiarity and vary based on contact [55, 110]. For example, infants who regularly see faces of diverse races do not show own-race preferences [111], and the own-race visual preferences emerges earlier for female faces than male faces [112], suggesting the preference is based on liking to look at the type of face that they encounter most often in their environment (own-race females).

Further, infants are better at recognizing individual novel faces own-race compared to other-race faces, and show the ability to form perceptual categories based on race [113–114]. As with visual preferences, these benefits are likely based on expertise for processing familiar faces: exposing infants to other-race faces in the laboratory can eliminate own-race facial recognition advantages [115–116]. Thus, infants’ visual responses to social categories (in terms of preferences and perceptual categorization) reflect adaptive learning about regularities in their social environment.

Are perceptual categories linked to conceptually-rich social knowledge or social expectations about category members? For example, does better categorization of own-race faces indicate expectations that members of the own-race group will share deep properties, or socially interact? As of yet, the closest evidence comes from a recent paper where infants associate own-race faces with happier music [117]. Although this finding could be relevant to early social bias, particularly since infants see music as social [118–119], it could also be due to familiarity without any social grouping or social expectations: infants have more exposure to own-race faces and positive music than to other-race faces and negative music. Thus, more research is needed to ask whether perceptual categorization reflects conceptually rich social expectations.

Even if perceptual categorization alone can’t be taken as evidence for conceptually rich social categorization, it may scaffold infants’ complex social reasoning. For example, a tendency to pay more attention to racial ingroup members could bias children towards learning only from own-race teachers [28], and seeing ingroup members as more relevant sources of information. And, paying less attention to outgroup members could lead to outgroup homogeneity [120–121], whereby people might view outgroup members as more similar to one another. Future research is needed to explore how early differences in visual attention may relate to later emerging conceptualizations of the social world.

Second, this differentiation could function in the reverse direction: humans may expect social group membership to influence novel individuals’ traits and patterns of social interaction, outside of forming preferences or dispreferences for groups. As example, someone could use the group identity “Italian” to infer properties of a person who belongs to that social group, such as what language she might speak, what foods she might prefer to eat, what religion she might practice, and which other people she might interact with. Someone could also make these inferences about a person holding a different group identity, such as “Japanese.” Although humans may have a tendency to automatically prefer their own group to all other groups [14], they could nonetheless make productive inferences about people from each of these two “outgroups,” without necessarily preferring one outgroup to the other.

At some point in development, social preferences and social categorization appear to operate in close coordination, and it is from this coordination that negative stereotypes, and other negative consequences of social categorization may be forged. One possibility is that one of these processes gives rise to the other. For example, early preferences, perhaps based on familiarity (Box 2), may set the stage for the later growth of conceptual social categories. Alternatively, children may quickly detect the category structure in the social world, and prejudice and stereotypes may result when category-based knowledge combines with children’s self-categorization and cues from society about the importance of social categories (Box 3). In contrast to each of these views, we propose that social preferences and rich category-based beliefs emerge in parallel early in development, and may not inevitably interact to form prejudice.

Box 3. Using functional relevance to form social groups.

Because any dimension could theoretically be (or become) meaningful for social categorization in a particular community, infants and children may be ready to detect groups based on any feature, if given the appropriate input [89]. Indeed, decades of research have indicated that humans show preferential treatment towards people to whom they share only a, “minimal,” similarity. For example, people prefer ingroup members even when the group is assigned and is based on an arbitrary (and untrue) personality feature, such as being “overestimators” [14]. Preferring “minimal” ingroup members begins early in childhood. In both classic experiments, like the Robber’s Cave [122], and more modern research [44, 123–125], children prefer other people who are in their randomly assigned group.

Preferences for minimal ingroup members likely don’t arise due to people thinking that the groups and random and meaningless, but rather could emerge because participants believe they share important features with others in their group (e.g., thinking that “overestimators” are more similar to one another than they are to “underestimators”), or believe that the groups must be functional, since the groups were labeled and used by a figure in power (e.g., the experimenter). Indeed, drawing attention to a category’s relevance, through labeling, generic statements, and functional use increases children’s likelihood of forming preferences for their minimal ingroup [65], increases their propensity to use minimal category membership to make inferences about characters’ behaviors [126], and heightens their expectations that members of the same minimal group will share essential similarities [66–67].

Together, these studies elegantly demonstrate that “minimal” characteristics, which are not typically seen as critical in our society can become relevant when attention is drawn to them in a laboratory context. However, although children form social preferences for minimal ingroup members, they show stronger group-level inferences and higher levels of own-group biases when reasoning about less arbitrary categories, like gender [31]. Future work is needed to determine whether these differences are due to the fact that children likely have more experience seeing these less arbitrary categories, like gender, used functionally in their communities, or due to certain categories being more readily used for social categorization regardless of a child’s particular experiences (Box 1). One type of research that may help resolve this debate would be work that investigates social cognition of children attend gender neutral preschools, who likely hear less gendered generic language and who likely see less gendered division of labor [127].

The origins of social preferences and social categorization in infancy

The bulk of research on infants’ early social reasoning focuses on early emerging visual and social preferences. As discussed earlier, infants spontaneously look longer at attractive faces, female faces, own-race faces, and faces of native language speakers [24,53–54,56], and babies show a familiar-race bias in face perception (see Box 2). Additionally, infants are more likely to approach, interact with, and imitate people who share their preferences or who speak their native language [24,57–63]. Although these visual and social preferences could be signs of early-emerging bias and prejudice, these preferences may instead operate completely differently from adult prejudice. For adults, ingroup favoritism is based on liking someone and rewarding them specifically because of their membership in the ingroup. That is, adults’ partiality towards the ingroup is depersonalized: it applies to all group members and does not depend on the perceiver being known by, or related to, the target [64]. Infants’ social preferences, on the other hand, could arise solely based on an affinity for more familiar individuals. In fact, infants could prefer particular individuals over others, without grouping preferred individuals into categories at all. Thus, although social preferences may have functional value, by guiding infants towards relevant social partners information [26] they do not per se indicate that infants are reasoning about people as members of conceptually rich social categories. Other evidence would be needed to demonstrate that infants could form inductively useful social categories.

Indeed, it is theoretically plausible that the ability to reason in sophisticated ways about people as members of social categories arises slowly and depends children acquiring information about members of social groups through observation of other people’s behaviors, and through older individuals’ explicit teaching and testimony. That is, children’s social categories could be grounded in the stereotypes and beliefs of adult members of their social and cultural community. Indeed, input from adults clearly influences children’s reasoning about social categories: children are more likely to see minimal social categories as informative when adults consistently label and use the categories functionally [65]. Hearing generic language about social categories leads children to be more likely to form a novel category [66], and to reason in essentialist ways about members of the novel group [67]. Such input could lead infants to move from forming preferences for familiar individuals, to forming adult-like preferences for people based on their identity as members of different social categories.

Alternatively, the ability to form relationally embedded social categories with inductive potential could plausibly be in place very early in life. A recent surge of research –outside of infants’ visual and social preferences—provides evidence infants have the cognitive capacities that may underlie conceptually rich social categorization. Infants can think about individual items as members of conceptual categories [68], form inductive inferences [69–70], and track complex social relationships [71–79]. Below we review evidence suggesting conceptually rich social categorization emerges early in life.

Looking time studies provide evidence for early conceptually rich social reasoning

Research using violation of expectation looking time methodologies, which assess infants’ responses to others’ actions and interactions, can provide a clearer view than measures of preference into infants’ ability to form conceptually rich social categories. In particular, because looking time studies ask about third-party expectations, these measures can elucidate whether infants reason in abstract ways about people as members of social groups, outside of any familiarity preferences. Violation of expectation studies on infants’ understanding of social groups evaluate whether infants use cues to group membership to form expectations about other people’s attributes and interactions. For example, in one set of studies, infants inferred that characters who moved in synchrony would subsequently perform the same action [78], suggesting they made the inductive inference that belonging to a group would influence each group member’s likely behavior.

One particularly illustrative test case of using violation of expectation studies to investigate infants’ ability to form abstract social categories comes from research on language as a marker of social group (Box 4). In these studies, we showed infants two native bilingual actors who were presented as members of the same group (either two English speakers or two Spanish speakers) or as members of different groups (one English speaker and one Spanish speaker). We then asked how infants used the information about the actors’ language to inform their expectations about the actors’ interactions and attributes. In one study, we asked whether infants expected the actors to affiliate with one another or to socially disengage from one another. Infants’ responses varied based on the actors’ group membership: infants who saw the actors both speak English looked longer when they disengaged, suggesting they expected affiliation, whereas infants who saw the actors speak different languages looked longer at affiliation, suggesting they found affiliation unexpected [76]. Thus, like adults and older children [45], infants expect people who speak a common language to engage, but they do not hold these same social expectations for people who speak different languages. These data suggest that infants view social relationships as embedded in broader shared social categories.

Box 4. Language is a potent cue to social structure.

Research on intergroup cognition often focuses on race, gender, and age. Indeed, adults and children are sensitive to these social categories, and use membership in them to guide their preferences and learning [2]. Yet, despite a wealth of evidence from the neighboring social sciences disciplines of linguistics and anthropology that language and accent serve as particularly reliable signals of social group membership [105–106], and that attention to language can surpass attention to visual cues in social categorization tasks [128–130], language is often overlooked in social psychology research on intergroup cognition [131].

The sociality of language emerges early: infants prefer native language speakers [24], and infants and children look to linguistic ingroup members to learn new information [26, 29, 57, 60, 62]. In fact, infants use language for more than personal decisions about whom to like or whom to learn from; they create conceptually rich social categories based on language, whereby they use language to make predictions about people’s likely traits and social interactions For example, they expect same-language speakers to be more likely to affiliate [77], and expect same-language speakers to share important social similarities, even when the language shared by the speakers is unfamiliar to them [80].

Language may inherently mark social group, and using language to divide the world into groups continues across development. Indeed, by preschool, children expect native speakers, but not foreign speakers, to follow social conventions [40], and children acquire linguistic stereotypes [132–133]. Does early language-based categorization feed into xenophobia? If so, which experiences mitigate these biases? In our research, infants raised in bilingual environments generalized information even across different-language speakers [80], suggesting multilingual exposure may cause people to be less likely to see language as marking concrete social boundaries. More work is needed to determine whether experiencing a diverse linguistic community could reduce stereotyping and prejudice, and, if so, whether the reduction in bias would be specifically in the domain of language (e.g., by increasing attitudes towards foreign speakers), or would be broader. These questions about the role of experience on impacting bias formation and reduction should also be asked about other social categories, including those typically studied (gender, race, and age), and those that are less studied, but potentially highly evolutionarily relevant (Box 1).

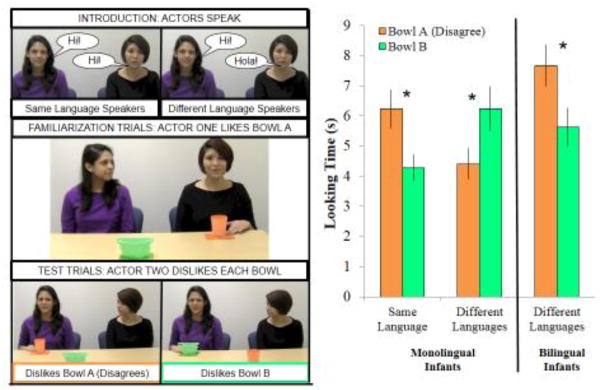

In another series of studies, we asked about 11-month-old infants’ inductive generalizations. After being presented with same-language or different-language speakers, infants were shown one speaker’s food preference. Subsequently, infants were shown the second speaker disagreeing with the first speaker (by disliking the previously liked food), or expressing a negative opinion of a previously uneaten food. Infants selectively generalized information across same-language speakers: they looked longer at the disagreement when the actors spoke the same language, but not when the actors spoke different languages, suggesting they found it unexpected for people from the same social group, but not all people, to disagree ([80]; Figure 1). Infants show a similar pattern of inductive generalization of labels: they expect people who speak the same language to use the same novel labels to refer to the same object [81], but do not expect people who speak different languages to use the same object labels [82].

Figure 1. Infants’ use of language when making inductive inferences.

This figure details methods and results from [65]. Monolingual infants generalized food preferences across same-language speakers, finding it unexpected when they disagree, but did not generalize food preferences across different-language speakers. On the other hand, infants from bilingual backgrounds generalized even across speakers of different languages.

Interestingly, infants’ inductive inferences based on shared language are not limited to speakers of a familiar language: infants are equally likely to generalize information across same-language speakers when the shared language is the infants’ native language (English) and when the shared language is unfamiliar to the infant (Spanish) [80]. Thus, infants’ expectations did not require any specific information or experience with that linguistic group to infer that people who speak the same language share relevant similarities.

An initial system for social categorization in infancy

Taken together, the findings from violation of expectation studies suggest that infants can generalize information selectively across same-language speakers, and make inferences about social relationships based on language. Therefore, at least in the case of language, infants’ social categorization shares critically important features of older children’s and adult’s social categorization: they use information about group membership to infer whether people will share properties, and how people will interact. Thus, conceptually-rich social categories emerge before verbally provided information can affect social knowledge, suggesting the ability to form social categories does not depend on explicit learning about the cultural or stereotypic content associated with different groups and the ability to use these categories to draw inferences about social structure likely drives social thinking and learning from early in ontogeny.

Although this recent work on infants’ inductive generalization and inferences about social relationships focuses on language categories, we hypothesize that infants could apply these same abstract features of social categorization to other groups that they think are socially important. Specifically, infants may have a system for thinking about people as members of social groups that is present early in ontogeny, such that infants are ready, early on, to apprehend and generalize information across individuals in a social category. Of course, children’s social category knowledge grows significantly across development, and social partners play an important role in this process. In particular, we expect that social experiences (such as the infants’ typical environment and the information n they receive from social partners) would modulate which features infants would see as relevant markers of social categories.

We hypothesize that infants begin by seeing specific features of human behavior as fundamentally relevant to social categorization (Box 1), and based on their social experiences, they learn to update the set of features they use to divide the social world into groups. Under this account, infants could require different experiences to form different social categories. That is, infants may initially expect that shared features that have defined group membership across human evolutionary history, such as language (Box 4), food preferences [80,83–84], and engagement in ritualistic actions [85], would mark people as members a social category. In contrast, infants would likely not see an arbitrary similarity, such as being randomly assigned to wear the same color mittens [61, 87], as defining membership in a conceptually rich social group.

However, with experience, infants and children likely update the list of dimensions that are seen as relevant for social categorization. Thus, although humans might have predispositions to attend to some markers of social division over others, the features that are relevant in each infant’s and each child’s community will certainly impact social categorization across development. For example, experience with group norms can lead children to form social categories based on dimensions that were not relevant in our evolutionary past, such as race (Box 1). Demonstrating the importance of social experiences on social thinking, minority race children, who likely have more experience thinking about race, reason about race as an important social category at earlier ages than majority race children [38, 88]. These ideas are consistent with Developmental Intergroup Theory (DIT), which suggests that any dimension that is marked and made salient in a child’s community (e.g., by explicit input from important social partners) may be able to be co-opted into the human system for reasoning about abstract social categories [89]. Indeed, this process likely underlies minimal group effects: researchers approximate social relevance by highlighting an arbitrary similarity, leading people to use the arbitrary feature as they would use an important social group marker (Box 3).

Malleability in the features that are seen as relevant for social categorization may also work in the reverse direction, such that even categories that served as fundamental social group markers may be abandoned based on early social experiences. As example, though we argue that language reliably marks social group, and may be prioritized in infants’ early social categorization, differences in infants’ sociolinguistic environments may influence whether they reason about language as marking social categories. Whereas infants from monolingual environments refrain from generalizing information across people who speak different languages, suggesting they may view different-language speakers as members of distinct social groups, infants from multilingual backgrounds generalize even across different-language speakers [80]. Therefore, infants who regularly see people who speak diverse languages interact may be less likely to use spoken language as a boundary for social groups. Thus, variations in important features of social environments could impact broader reasoning about the social world. Future research should ask how social experiences influence categorization on both potentially prioritized dimensions and on dimensions that humans may learn are important via social transmission (see Outstanding Questions Box).

Outstanding Questions Box.

Role of self-categorization: How early do infants and children self-categorize into social groups? Can conceptually-rich social categories exist prior to the development of a sense of self? How does acquiring a sense of self and self-categorization influence social categorization, social preferences, and prejudice? How does the social status of the groups to which the child self-categorizes impact social learning, own-group preferences, and prejudice? What happens when children identify with more than one group?

Role of social experience: What types of experiences influence infants’ social categorization? Is the link between experience and social categorization specific (e.g., language experience impacts thinking about language as a social marker) or broad (e.g., language experience leads to more flexible categorization generally)? Are early social experiences more important than later ones? How does experience impact both the tendency to create a category at all, as well as the tendency to use that category to make social inferences?

Malleability of prejudice: What types of interventions most successfully reduce prejudice? Do the same interventions work across the lifespan? Does reducing a social preference based on one social category (e.g., race) reduce social preferences or prejudice more broadly (e.g., change gender stereotypes)?

Priorities in social categorization: Which social boundaries are infants most likely to attend to? Are infants’ earliest social categories based on dimensions that have fundamentally marked social groups across human evolutionary history? Is reasoning about potentially prioritized social categories less malleable than reasoning about social categories that are acquired later? Are categories that are learned to be important based on social input (e.g., race) used identically to potentially prioritized categories once they are acquired?

Using malleability of social categorization to reduce social prejudice

Although human infants may be ready to form conceptually rich social categories, the fact that forming generative inferences based on category membership can, in theory, be separated from dislike of the outgroup [1], and the fact that the particular dimensions upon which humans form social categories are malleable [38, 80], suggests that prejudice against members of particular social groups is not inevitable. Developmental research sheds light on the relationship between categorization and preference formation, suggesting that studying human reasoning across the lifespan is critical for understanding the emergence and malleability of intergroup bias. Specifically, important future studies will continue to investigate how and when social preferences and conceptual reasoning about social groups come to operate together, leading to prejudice and discrimination. One possibility is that children first forming simple preferences for familiar people, and then later generalize these positive associations to personally unfamiliar members of their broader social group, leading them to show ingroup positivity [64] and eventually outgroup negativity [52]. Or, children’s may form conceptually rich social categories, and then come to self-identify with one category, at which point they may begin to show adult-like depersonalized preferences for members of their own group, leading to bias (Outstanding Questions).

One particularly important area for future study involves investigating how parents and educators can limit the transmission of bias. One prominent way that adults transmit information about social categories is through their language. For instance, generic language refers to groups rather than individuals, (e.g., “boys like X,” or “Hispanics live in Y”), signifying that groups are enduring, highlighting group differences, and teaching children that the group distinction is meaningful. Indeed, hearing generic statements about a novel social group increases the likelihood that children form a conceptually rich social category, and can lead children to develop essentialist thoughts and stereotypes about the novel group [65–67]. Thus, parents and educators may strive to speak about people as individuals (e.g., “This boy likes X”) rather than speaking about whole categories of people, in order to reduce essentialist tendencies.

As a caveat, it is impossible, and potentially counterproductive, to avoid all conversation that remarks on people’s social group membership. Indeed, research on “colorblind” interventions shows that purposefully refraining from all discussion of a category (in this case, race) can be ineffective and can even lead to increased prejudice [90–91]. Nevertheless, focusing on people as being distinctive individuals, as opposed to members of groups with collective properties, is one area in which language can be used in smart ways to potentially reduce children’s tendency to form a new conceptually rich social category, and to lower the transmission of bias towards members of the highlighted social group. In support of this idea, introducing people to counter-stereotypic individuals from a certain social group has been one of the most effective ways to reduce implicit bias for both adults [92] and children [93].

Rather than trying to halt the formation of social categorization in the first place, many interventions have focused on reducing the social significance that people ascribe to the categories to which other people belong. For example, interventions aimed at reducing prejudice based on gender and race have successfully led to less explicit and implicit bias, to smoother cross-group interactions, and even to increased overt actions aimed at promoting equality [94–96]. These interventions probably do not change the likelihood that adults categorize people into social groups, but rather may help participants change the perceptions, beliefs, and stereotypes they ascribe to those social categories. Interesting future questions concern how to leverage the insight gained by studies of bias reduction among adults to create manipulations that are effective with children. Indeed, current research suggests that implicit associations are malleable based on new information [97–98], and that similar interventions could be effective for adults and children [92–93]. Indeed, efforts to change the structure of social categorization among children may be even more impactful, since children have less experience, meaning their stereotypes and bias may be less entrenched and easier to overcome.

Concluding Remarks

Social categorization has vast implications for myriad aspects of human social life. Here we present evidence that developmental psychology can inform scientists’ understanding of the mechanisms underlying social categorization and its downstream negative consequences. To do this, we aimed at providing a review of developmental research on social categorization, and argued that conceptually rich social categorization is functionally different than social preferences for individual members of social groups. Separating these two processes can lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms and implications of each type of data. Although these constructs may act in tandem in adulthood, it is theoretically and empirically possible to separate them: having a social preference for people from a familiar background does not require reasoning about abstract similarities between group members, and the initial formation of social predictions based on social categories does not obligate a preference or dispreference toward a particular group. In fact, although hearing generic language increases essentialist reasoning about novel social groups [65–67], children who hear generic language about a novel social group do not initially show lower levels liking for members that group compared to children who heard specific language about members of the novel group [99]. Even for adults, higher levels of essentialist reasoning are not always related to higher levels of prejudice towards social groups [100]. Therefore, even if forming social categories and making social inferences based on these categories is a basic part of human cognition, prejudice is not inevitable.

There are still many open questions regarding the origins of social categorization (Outstanding Questions), including questions about which dimensions infants’ see as fundamentally relevant to social categorization (Box 1), and about how experience across the lifespan shapes use of these social categories in real interactive contexts (Box 3). However, this growing body of research suggests that an ability to see people as members of social groups, and to use these groups to inform inferences about the social world emerges in infancy. Clarity in the evidence deemed necessary to demonstrate conceptually rich social categorization in infancy will propel these important inquiries forward.

Trends Box.

Social preferences for ingroup members emerge in the first year of life.

Preferring to look at or to interact with familiar or similar others does not necessarily indicate an ability to form abstract, inductively-rich social categories

Recent studies using violation of expectation looking time methods provide clearer evidence that infants can form conceptually rich social categories

Infants use social group boundaries to guide their inductive generalizations and expectations about social relationships.

Social categorization and social preferences are each malleable based on input, experience, and interventions, suggesting prejudice may not be inevitable

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiske ST, Neuberg SL. A continuum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1990;23:1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weisman K, et al. Young children’s automatic encoding of social categories. Developmental Sci. 2015;18:1036–1043. doi: 10.1111/desc.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruner JS. On perceptual readiness. Psychol Rev. 1957;64:123–152. doi: 10.1037/h0043805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelman SA. The essential child: Origins of essentialism in everyday talk. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland SL, et al. Memory errors reveal a bias to spontaneously generalize to categories. Cognitive Sci. 2015;29(5):1021–1046. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badger JR, Shapiro LR. Category structure affects the developmental trajectory of children’s inductive inferences for both natural kinds and artefacts. Think Reasoning. 2015;21(2):206–229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelman SA, Davidson NS. Conceptual influences on category-based induction. Cognitive Psychol. 2013;66:327–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker CM, et al. Explaining prompts children to privilege inductively rich properties. Cognition. 2014;133:343–357. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiske ST, Neuberg SL. Category-based and individuating processes as a function of information and motivation: evidence from our lab. In: Bar-Tal D, et al., editors. Steroyping and Prejudice: Changing Conceptions. Springer Science Press; 2013. pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodenhausen GV, et al. Social categorization and the perception of social groups. In: Fiske ST, Macrae CN, editors. The Sage Handbook of Social Cognition. Sage Publications Limited; 2012. pp. 318–336. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Basic Books; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris LT, Fiske ST. Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: neuroimaging responses to extreme outgroups. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(10):847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajfel H, et al. Social categorization and intergroup behavior. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1971;1(2):149–178. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu X, et al. Do you feel my pain? Racial group membership modulates empathic neural responses. J Neurosci. 2009;29(26):8525–8529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2418-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haslam N, Stratemeyer M. Recent research on dehumanization. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;11:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neuberg SL, Descioli P. Prejudices: Managing perceived threats to group life. In: Buss DM, editor. The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. Wiley Press; 2015. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amodio DM, Devine PG. Stereotyping and evaluation in implicit bias: Evidence for independent constructs and unique effects on behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;91(4):652–661. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zajonc RB. Feeling and thinking: preferences need no inferences. Amer Psychol. 1980;35(2):151–175. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherman SJ, et al. Stereotype development and formation. In: Carlston D, editor. Oxford Handbook of Social Cognition. Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 548–574. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziv T, Banaji MR. Representations of social groups in the early yers of life. In: Fiske ST, Macrae CN, editors. The Sage Handbook of Social Cognition. Sage Publications Limited; 2012. pp. 372–389. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunham Y, et al. The development of implicit intergroup cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;12(7):248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunham Y, Emory J. Of affect and ambiguity: the emergences of preferences for arbitrary groups. J Soc Issues. 2014;70(1):81–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinzler KD, et al. The native language of social cognition. P Nat A Sci USA. 2007;104(30):12577–12580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705345104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renno MP, Shutts K. Children’s social category-based giving and its correlates: Expectations and preferences. Dev Psychol. 2015;51(4):533–543. doi: 10.1037/a0038819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Begus K, et al. Infants’ preferences for native speakers are associated with an expectation of information. P Nat A Sci USA. 2016;113(44):12397–12402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603261113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egalite AJ, et al. Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement. Econ Edu Rev. 2015;45:44–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaither S, et al. Monoracial and biracial children: effects of racial identity salience on social learning and social preferences. Child Dev. 2014;85(6):2299–2316. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kinzler KD, et al. Children’s selective trust in native-accented speakers. Developmental Sci. 2011;14(1):106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shutts K, et al. Social categories guide young children’s preferences for novel objects. Developmental Sci. 2010;13(4):599–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunham Y, et al. Constraints of “minimal” group affiliation in children. Child Dev. 2011;82(3):793–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan JJ, et al. Development of in-group favoritism in children’s third-party punishment of selfishness. P Nat A Sci USA. 2014;111(35):12710–12715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402280111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diesendruck G, HaLevi H. The role of language, appearance, and culture in children’s social category-based induction. Child Dev. 2006;77(3):539–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirschfeld L. Race in the making. MIT University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalish CW. Generalizing norms and preferences within social categories and individuals. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(4):1133–1143. doi: 10.1037/a0026344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor MG, et al. Boys will be boys; cows will be cows: Children’s essentialist reasoning about gender categories and animal species. Child Dev. 2009;79:1270–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waxman SR. Names will never hurt me? Naming and the development of racial and gender categories in preschool aged children. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2010;40(4):593–610. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinzler KD, Dautel J. Children’s essentialist reasoning about language and race. Developmental Sci. 2012;15:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhodes M, et al. Preschool ontology: The role of beliefs about category boundaries in early categorization. J Cogn Dev. 2014;15(1):78–93. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2012.713875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liberman Z, et al. Children’s expectations about conventional and moral behaviors of ingroup and outgroup members. J Exp Child Psychol. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.03.003. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts SO, et al. So it is, so it shall be: Group regularities license children’s prescriptive judgments. Cogn Sci. doi: 10.1111/cogs.12443. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt MFH, et al. Young children enforce social norms selectively depending on the violator’s group affiliation. Cognition. 2012;124(3):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misch A, et al. Stick with your group: Young children’s attitudes about group loyalty. J Exp Child Psychol. 2014;126:19–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Plotner M, et al. What is a group? Young children’s perceptions of different types of groups and group entitativity. PLOS One. 2016;11(3):e015200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhodes M, Chalik L. Social categories as markers of intrinsic interpersonal obligations. Psychol Sci. 2013;6:999–1006. doi: 10.1177/0956797612466267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shutts K, et al. Children’s use of social categories in thinking about people and social relationships. J Cogn Dev. 2013;14(1):35–62. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2011.638686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rhodes M. How two intuitive theories shape the development of social categorization. Child Dev Persp. 2013;7(1):12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhodes M, Gelman SA. A developmental examination of the conceptual structure of animal, artifact, and human social categories across two cultural contexts. Cogn Psychol. 2009;59(3):244–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalish CW, Lawson CA. Development of social category representations: Early appreciation of roles and deontic relations. Child Devel. 2008;79(3):577–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rhodes M, Brickman D. The influence of competition of children’s social categories. J Cogn and Dev. 2011;12(2):194–221. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chalik L, Rhodes M. Preschoolers use social allegiances to predict behavior. J Cogn and Dev. 2014;15(1):136–160. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aboud FE. The formation of in-group favoritisim and out-group prejudice in young children: Are they distinct attitudes? Dev Psychol. 2003;39(1):48–60. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slater A, et al. Newborn infants prefer attractive faces. Inf Behav Dev. 1998;21(2):345–354. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anzures G, et al. Developmental origins of the other-race effect. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22(3):173–178. doi: 10.1177/0963721412474459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones BC, et al. Facial symmetry and judgments of apparent health: Support for a “good genes” explanation of the attractiveness-symmetry relationship. Evol Human Behav. 2001;22(6):417–429. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quinn PC, et al. Representations of the gender of human faces by infants: A preference for female. Perception. 2002;31(9):1109–1121. doi: 10.1068/p3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buttelmann D, et al. Selective imitation of in-group over out-group members in 14-month-old infants. Child Dev. 2013;84:422–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fawcett CA, Markson L. Similarity predicts liking in 3-year-old children. J Exper Child Psychol. 2010;105:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gerson SA, et al. Do you do as I do? Young toddlers prefer and copy toy choices of similarly acting others. Infancy. 2016 doi: 10.1111/infa.12142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howard LH, et al. Neighborhood linguistic diversity affects social learning in infants. Cognition. 2014;133:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mahajan N, Wynn K. Origins of “us” versus “them”: prelinguistic infants prefer similar others. Cognition. 2012;124(2):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shutts K, et al. Social information guides infants’ selection of foods. J Cogn Dev. 2009;10(2):1–17. doi: 10.1080/15248370902966636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Schaik JE, Hunnius S. Little chameleons: The development of social mimicry during early childhood. J Exper Child Psychol. 2016;147:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.64 MB. The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? J Soc Issues. 1999;55(3):429–444. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bigler RS, et al. Social categorization and the formation intergroup attitudes in children. Child Dev. 1997;68(3):530–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rhodes M, et al. The role of generic language in the early development of social categorization. Child Dev. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12714. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rhodes M, et al. Cultural transmission of social essentialism. P Nat A Sci USA. 2012;109(34):13526–13531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208951109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Havy M, Waxman SR. Naming influencing 9-month-olds’ identification of discrete categories along a perceptual continuum. Cognition. 2016;156:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDonough L, Mandler JM. Inductive generalization in 9- and 11-month-olds. Developmental Sci. 2002;1(2):227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vukatana E, et al. One is not enough: Multiple exemplars facilitate infants’ generalizations of novel properties. Infancy. 2015;20(5):548–575. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mascaro O, Csibra G. Representation of stable social dominance relations by human infants. P Nat A Sci USA. 2012;109(18):6862–6867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113194109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pun A, et al. Infants use relative numerical group size to infer social dominance. P Nat A Sci USA. 2016;113(9):2376–2381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514879113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Geraci A, Surian L. The developmental roots of fairness: Infants’ reactions to equal and unequal distributions of resources. Developmental Sci. 2011;14(5):1012–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sloane S, et al. Do infants have a sense of fairness? Psychol Sci. 2012;23(2):196–204. doi: 10.1177/0956797611422072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choi Y, Luo Y. 13-month-olds’ understanding of social interactions. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(3):274–283. doi: 10.1177/0956797614562452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liberman Z, Kinzler KD, Woodward AL. Friends or foes: Infants use shared evaluations to infer others’ social relationships. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143(3):966–971. doi: 10.1037/a0034481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liberman Z, et al. Preverbal infants infer third-party social relationships based on language. Cogn Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1111/cogs.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Powell LJ, Spelke ES. Preverbal infants expect members of social groups to act alike. P Nat A Sci USA. 2013;110(41):E3965–E3972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304326110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rhodes M, et al. Infants’ use of social partnerships to predict behavior. Developmental Sci. 2015;18(6):909–919. doi: 10.1111/desc.12267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liberman Z, et al. An early-emerging system for reasoning about the social nature of food. P Nat A Sci USA. 2016;113(34):9480–9485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605456113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Buresh JS, Woodward AL. Infants track action goals within and across agents. Cognition. 2007;104(2):287–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scott JC, Henderson AME. Language matters: Thirteen-month-olds understand that the language a speaker uses constrains conventionality. Dev Psychol. 2013;49(11):2102–2111. doi: 10.1037/a0031981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fischler C. Food, self and identity. Social Sci Info. 1988;27(2):275–292. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shutts K, et al. Understanding infants’ and children’s social learning about foods: Previous Research and new prospects. Developmental Psychol. 2013;49(3):419–425. doi: 10.1037/a0027551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Legare CH, Harris PL. The ontogeny of cultural learning. Child Development. 2016;87(3):633–642. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.

- 87.Wynn K. Origins of value conflict: Babies do not agree to disagree. Trend in Cogn Sci. 2016;20(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roberts SO, Gelman SA. Can White children grow up to be Black? Children’s reasoning about the stability of emotion and race. Dev Psychol. 2016;52(6):887–893. doi: 10.1037/dev0000132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bigler RS, Liben LS. Developmental intergroup theory: Explaining and reducing children’s social stereotyping and prejudice. Curr Dir in Psycholog Sci. 2007;16(3):162–166. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Apfelbaum EP, et al. Seeing race and seeming racist? Evaluating strategic colorblindness in social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(4):918–932. doi: 10.1037/a0011990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Correll J, et al. Colorblind and multicultural prejudice reduction strategies in high-conflict situations. Group Process Interg. 2008;11(4):471–491. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lai CK, et al. Reducing implicit racial prejudice: A comparative investigation of 17 interventions. J Exp Psychol General. 2014;143(4):1765–1785. doi: 10.1037/a0036260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gonzalez AM. Reducing children’s implicit racial bias through exposure to positive out-group exemplars. Child Dev. 2017;88(1):123–130. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carnes M, et al. Effects of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: A cluster, randomized control trial. Acad Med. 2015;90(2):221–230. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carr PB, et al. “Prejudiced” behavior without prejudice? Beliefs about the malleability of prejudice affect interracial interactions. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;103(3):452–471. doi: 10.1037/a0028849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Devine PG, et al. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2012;48(6):1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gonzalez AM, et al. Malleability of implicit associations across development. Developmental Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1111/desc.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mann TC, Ferguson MJ. Can we undo our first impressions? The role of reinterpretation in reversing implicit evaluations. J Pers Soc Psyc. 2015;108(6):823–849. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rhodes M. How does social essentialism affect the development of intergroup relations? Developmental Sci. doi: 10.1111/desc.12509. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haslam N, et al. Are essentialist beliefs associated with prejudice? Brit Journ of Devel Psychol. 2002;41(1):87–100. doi: 10.1348/014466602165072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kurzban R, et al. Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. P Nat A Sci USA. 2001;98(26):15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pauker K, et al. Race essentialism and contextual differences in children’s racial stereotyping. Child Dev. 2016;87:1409–1422. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gaither SE, et al. Essentialist thinking predicts decrements in children’s memory for racially ambiguous faces. Developmental Psychol. 2014;50(2):482–488. doi: 10.1037/a0033493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Olson KR, et al. Gender cognition in transgender children. Psycholog Sci. 2015;26(4):467–474. doi: 10.1177/0956797614568156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cohen E. The evolution of tag-based cooperation in humans: the case for accent. Curr Anthropol. 2012;53(5):588–616. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Henrich J, Henrich N. Why humans cooperate: A cultural and evolutionary explanation. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Peryam DR. The acceptance of novel foods. Food Tech. 1963;17:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rozin P, Siegal M. Vegemite as a marker of national identity. Gastrology. 2003;3:63–67. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rennels JL, et al. Asymmetries in infants’ attention toward and categorization of male faces: The potential role of experience. J Exper Child Psychol. 2016;142:137–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kelly DJ, et al. Three-month-olds, but not newborns, prefer own race faces. Developmental Sci. 2005;8(6):31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.0434a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bar-Haim Y, et al. Nature and nurture in own-race face processing. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(2):159–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu S, et al. Asian infants show preference for own-race but not other-race female faces: The role of infant caregiving arrangements. Front Psychol. 2015;6:593. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hayden A, et al. The other-race effect in infancy: Evidence using a morphing techniques. Infancy. 2007;12(1):95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2007.tb00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kelly DJ, et al. Development of the other-race effect during infancy: Evidence toward universality? J Exp Child Psychol. 2009;104(1):105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sangrigoli S, de Schonen S. Recognition of own-race and other-race faces by three-month-old infants. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2004;45(7):1219–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Heron-Delaney M, et al. Perceptual training prevents the emergence of the other-race effect during infancy. PLOS One. 2011;6(5):1–5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Xiao NG, et al. Older but not younger infants associate own-race faces with happy music and other-race faces with sad music. Developmental Sci. doi: 10.1111/desc.12537. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mehr SA, Spelke ES. Shared musical knowledge in 11-month-old infants. Developmental Sci. doi: 10.1111/desc.12542. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mehr SA, et al. For 5-month olds melodies are social. Psycholog Sci. 2016;27(4):486–501. doi: 10.1177/0956797615626691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Doyle AB, Aboud FE. A longitudinal study of White children’s racial prejudice as a social-cognitive development. Merrill-Palmer Quar. 1995;41(2):209–228. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Park B, Rothbart M. Perception of out-group homogeneity and levels of social categorization: Memory for the suboridinate attributes of in-group and out-group members. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982;42(6):1051–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sherif M, et al. The robbers cave experiment: Intergroup conflict and cooperation. Wesleyan University Press; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Baron AS, et al. Constraints on the acquisition of social category concepts. J Cogn Dev. 2014;15(2):238–268. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Plotner M, et al. The effects of collaboration and minimal-group membership on children’s prosocial behavior, liking, affiliation, and trust. J Exp Child Psychol. 2015;139:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Richter N, et al. The effects of minimal group membership on young preschoolers’ social preferences, estimates of similarity, and behavioral attribution. Collabra. 2016 doi: 10.1525/collabra.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Baron AS, Dunham Y. Representing “Us” and “Them”: Building blocks of intergroup cognition. J Cogn Dev. 2015;16(5):780–801. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Shutts K, et al. Gender-neutral pedagogy influences preschoolers’ social cognition about gender. Presented at the Society for Research in Child Development.2015. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hansen K, et al. Competent and warm?: How mismatching appearance and accent influence first impressions. Exp Psychol. 2017;64:27–36. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169/a000348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pietraszewski D, Schwartz A. Evidence that accent is a dimension of social categorization, no a byproduct of coalitional categorization. Evol Human Behav. 2014;35:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rakic T, et al. Blinded by the accent! The minor role of looks in ethnic categorization. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100(1):16–29. doi: 10.1037/a0021522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gluszek A, Dovidio JF. The way they speak: a social psychological perspective on the stigma of non-native accents in communication. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2010;14(2):214–237. doi: 10.1177/1088868309359288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kinzler KD, DeJesus JM. Northern=smart and Southern=nice: The development of accent attitudes in the U.S. Q J Exp Psychol. 2013;66:1146–1158. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2012.731695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kinzler KD, DeJesus JM. Children’s sociolinguistic evaluations of nice foreigners and mean Americans. Developmental Psychol. 2013;49(4):655–664. doi: 10.1037/a0028740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]