Abstract

Purpose

To clarify whether the incidence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) and the overlap of MetS components are affecting the ocular circulation shown by laser speckle flowgraphy (LSFG).

Materials and Methods

We studied 76 consistent patients. Blowout score (BOS) and blowout time (BOT), which are the pulse waveform analysis parameters, and mean blur rate (MBR) using LSFG in the optic nerve head (ONH) and choroid were evaluated. Throughout, the ONH was separated out from the vessels and tissue for analysis and MBRs in the ONH were divided into four sections (superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal).

Results

Thirty-two patients were diagnosed having Mets. MBR-Tissue (P = 0.003), MBR-All (P = 0.01), MBR-Choroid (P = 0.04), and BOS-Choroid (P = 0.03) were significantly lower in patients with MetS than in the patients without MetS. Multiple-regression analysis revealed the temporal side of MBR-Tissue and BOS-Choroid which were identified as factors contributing independently to the overlap of the MetS components. Multiple-regression analysis also revealed that the MetS components were identified to be factors independently contributing to the BOS-Choroid and temporal side of MBR-Tissue.

Conclusion

Our study clarified that the incidence of MetS and the overlap of the MetS components are significantly affecting the ONH and choroidal microcirculation.

1. Introduction

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) refers to a cluster of metabolic abnormalities, including obesity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. MetS increases the risk for diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease and then increases morbidity and mortality [1–4]. Numerous researchers reported that subjects with MetS had significantly greater carotid intima-media thickness (IMT) compared with subjects without MetS [5–10] and the IMT increases with each additional component of MetS [11]. The reports of the relationship between MetS and cardiac function have revealed that MetS were independently associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction [12–15].

Laser speckle flowgraphy (LSFG) is a safe and quantitative devise for evaluating of ocular circulation [16, 17]. This is based on a change in patterns of the speckles of the laser light reflected from a retina and choroid [18, 19]. LSFG depends on the red blood cells in the optic nerve head (ONH), choroid, and retina; the mean blur rate (MBR) is a unique index of blood flow of LSFG [20, 21]. The LSFG-NAVI™ (Softcare Co., Fukuoka, Japan) was approved in 2008 as a medical apparatus by Japan's Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency and in 2016 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Variations in the MBR have pulse wave patterns that are synchronized with the cardiac cycle. We reported that the blowout time (BOT) and blowout score (BOS), factors obtained from a pulse waveform analysis, were significantly correlated with arteriosclerosis and left ventricular diastolic status [22–24]. We hypothesized that the cluster of components of MetS may affect the ocular circulation shown by LSFG. The purpose of the present study was thus to clarify whether the incidence of MetS and the overlap of MetS components are affecting the ocular circulation in the ONH and choroid shown by the LSFG, while comparing them with IMT and left ventricular diastolic function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

The design of the current study was cross-sectional comparative study.

The institutional review board of Toho University Sakura Medical Center approved the present study (numbers 2011-009 and 2010-012). All participants provided informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. We studied 76 consistent patients who had undergone polysomnography (a test for sleep apnea) and were able to detect the MetS components accurately, at the Department of Cardiovascular Center of Toho University Sakura Medical Center between January 18, 2010, and June 12, 2013. Patients were excluded if they had atrial fibrillation, glaucoma, uveitis, optic neuropathy, vitreous or retinal disease, or retinal or choroidal vascular disease or if they had undergone a previous intraocular surgery. All patients were evaluated while they were hospitalized.

2.2. Measurements of Mean IMT

We have described the precise method of measurements of mean IMT in our previous report [25]. Briefly, high-resolution ultrasonographic imaging of the carotid artery using the B-scan mode was performed using the EUB-8500 ultrasound system (Hitachi Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with the probe frequency set to 7.5 MHz. Imaging was performed with the patients in a supine position with their heads turned slightly away from the sonographer. The procedure involved scanning the near and far walls of the carotid artery every 1 centimeter proximal to the carotid bulb in the longitudinal view. The mean IMT was defined as the average of the maximal IMT 1 centimeter proximal and 1 centimeter distal to the carotid bulb [26, 27]. The mean IMT of the thickened side of the carotid artery was used for data analyses.

2.3. Measurements of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function

We have described the precise method of measurements of left ventricular diastolic function in our previous report [25]. Briefly, left ventricular diastolic function was assessed according to the recent consensus guidelines [28, 29] on diastolic function evaluation measuring mitral inflow velocities (E-wave) using pulse wave Doppler in the apical four-chamber view. The pulse wave tissue Doppler velocities were acquired at end-expiration, in the apical four-chamber view, with the sample positioned at the lateral mitral annulus, measuring early diastolic (e' velocity) and calculating the E/e' ratio. The E/e' ratio has been reported to be the single best predictor of the left ventricle diastolic filling pressure [30]. Echocardiography was performed using a commercially available instrument (Vivid 7, GE Healthcare, Japan).

2.4. Laboratory Measurements and Systemic Parameters

The following values were measured: fasting blood sugar (FBS: mg/dl), total cholesterol (mg/dl), triglycerides (mg/dl), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C: mg/dl), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C: mg/dl), homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), hematocrit (%), and creatinine (mg/dl) obtained from fasting morning blood samples. HOMA-IR = fasting insulin (IU/ml) × fasting blood glucose (mmol/l)/22.5 [31]. The body mass index (BMI: kg/m2), systolic blood pressure (SBP: mmHg), diastolic blood pressure (DBP: mmHg), and heart rate (beats per min, bpm) were evaluated.

2.5. Diagnosis of MetS

The definition by the Japanese Committee to Evaluate Diagnostic Standards for Metabolic Syndrome was used for the diagnosis of MetS [32, 33]. This definition is based on abdominal obesity (waist ≥ 85 cm for men and ≥90 cm for women) plus two or more components of metabolic risk factors, (1) hypertension: SBP ≥ 130 mmHg or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg or those who had been treated for hypertension, (2) dyslipidemia: HDL-C < 40 mg/dl or triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dl or a history of previous treatment for dyslipidemia, and (3) high glucose: FBS ≥ 110 mg/dl or a history of previous treatment for diabetes.

2.6. LSFG Measurements

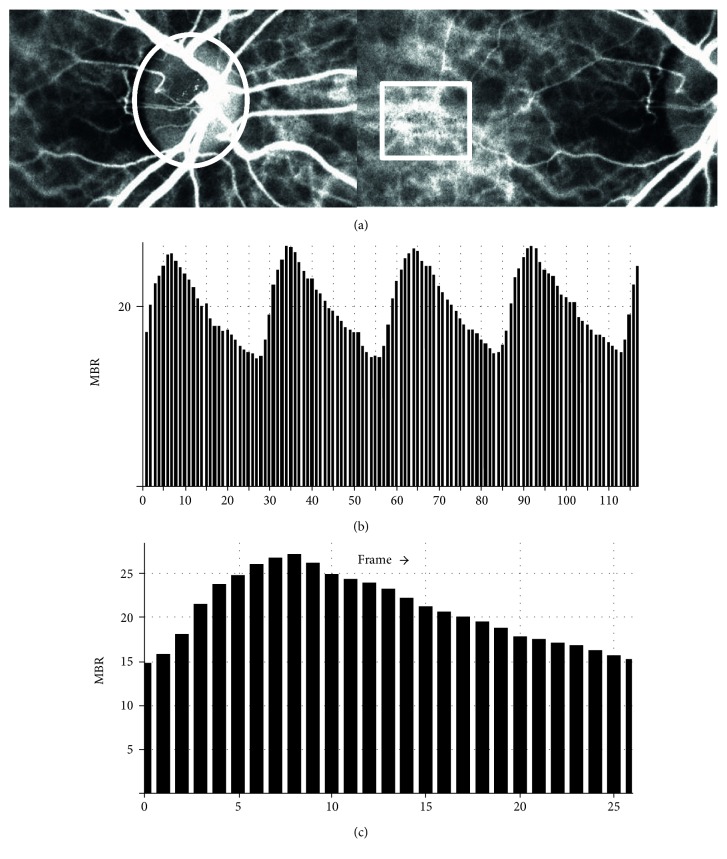

The details of the determination of the LSFG measurements from fundus images were as described [21, 34]. We have described the methods of average MBR, BOT, and BOS which are items of pulse waveform in our previous report [35]. Briefly, for the evaluation of the ONH and choroidal blood flow, a circle was set surrounding the ONH, and the center of a rectangle was placed at the foveal area avoiding the retinal vessel (Figure 1, upper panel).

Figure 1.

The method for analyzing the mean blur rate (MBR) and pulse waveform in the optic nerve head (ONH) and choroid circulation using LSFG. (a) The gray-scale map of the total measurement area. The circle and rectangle designates the area of the ONH and center placed at the foveal area avoiding the retinal vessel measured. (b) The pulse waves show changes in the MBR, which is tuned to the cardiac cycle for 4 seconds. The total number of frames is 118. (c) Normalization of one pulse. MBRs are made on this screen.

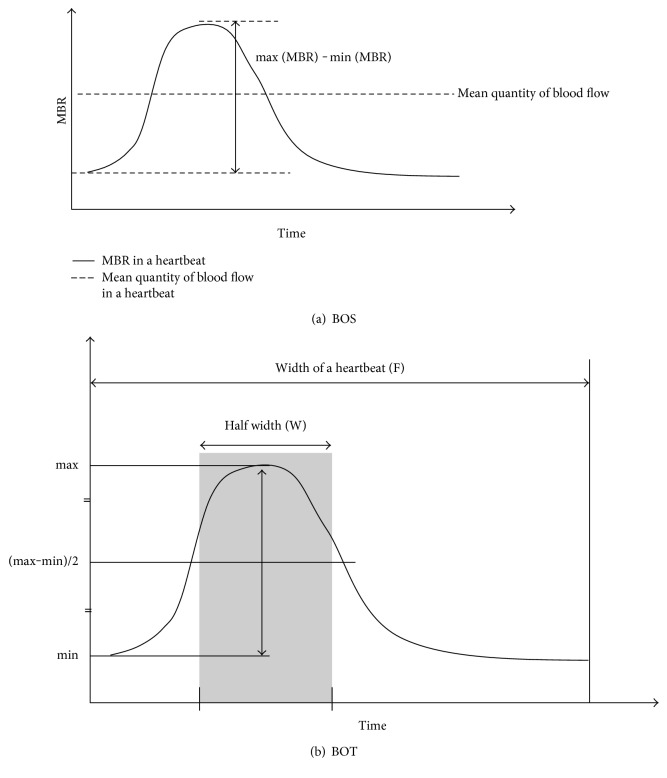

First, 118 MBR images (118 frames) were recorded from the circle and the rectangle area within a 4 sec period tuned to the cardiac cycle. On the analysis screen, the pulse wave of the changing MBR values which corresponded to each cardiac cycle was obtained (Figure 1(b)). The analysis of the screen which is normalized to one pulse is then displayed (Figure 1(c)), and the analysis of the pulse waveform and average MBR is made on this screen. In the present study, the LSFG used the mean MBR as an indicator of blood flow. The BOS and BOT were also calculated. Figure 2 shows the schematic explanations of the BOS (Figure 2(a)) and BOT (Figure 2(b)) obtained from waveform analysis. And the BOS and BOT values were determined by the following formulae [21]:

| (1) |

Figure 2.

Schematic explanation of the blowout score (BOS) and blowout time (BOT) obtained from pulse waveform analysis.

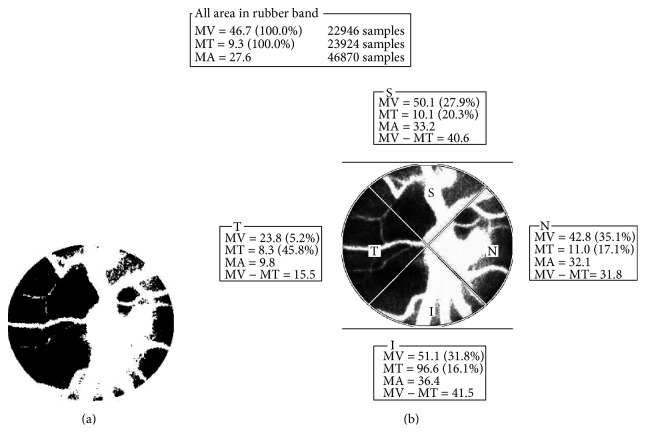

We calculated parameters using LSFG Analyzer software (v.3.0.47, Softcare Co. Ltd., Fukuoka, Japan). Next, the software separated out the vessels using the automated definitive threshold (Figure 3(a)) and then analyzed the means of the MBR, BOS, and BOT in the ONH tissue (Tissue), in the vessels of the ONH (Vessel), and throughout the ONH (All). Finally, MBRs in the ONH were divided into four sections (superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal: Figure 3(b)). All patients were measured in a seated position, and pupils were dilated with 0.5% tropicamide eye drops. Only the data from the right eye were used for the analysis.

Figure 3.

The software segments out the retinal vessels using the automated definitive threshold throughout the ONH, within the ONH vessel (shown in white) and within the ONH tissue (shown in black) (a). Next, the software divided into 4 sections (superior, temporal, inferior and nasal) (b) and analyzes the mean blur rate in the each section. T = temporal; N = nasal; S = superior; I = inferior.

2.7. Measurements of Other Ocular Parameters

The following parameters of right eyes were measured: spherical refraction (diopters (D)) assessed with the TONOREF 2™ system (NIDEK Co., Aichi, Japan), intraocular pressure (IOP, mmHg) measured by applanation tonometry, and ocular perfusion pressure (OPP, mmHg). The OPP was defined as (2/3 mean arterial blood pressure) − IOP.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the means ± standard deviations for the continuous variables.

Unpaired t-test, Yates 2 × 2 chi-square test, 2 × 2 chi-square test, and Fisher's exact probability were used for comparison of clinical and ocular variables between patients with MetS and those without MetS. Single-regression analyses were used to determine the relationship between the overlap of the MetS components and all of the LSFG parameters. Multiple-regression analyses were used to determine the independent factors for MetS components and the LSFG parameters which were significantly correlated with the MetS components. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. The StatView v 5.0 program (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical analyses.

3. Results

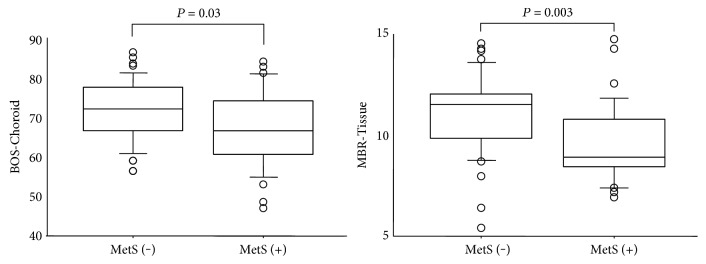

Tables 1 and 2 show the results of a comparison of clinical and LSFG parameters in patients with and without MetS. Thirty-two patients were diagnosed having MetS. The ratio of men, BMI, E/e' ratio, FBS, triglyceride, HOMA-IR, and frequency of hypertension and diabetes were significantly higher in the patients with MetS than in the patients without MetS. MBR-Tissue, MBR-All, MBR-Choroid, and BOS-Choroid were significantly lower in patients with MetS than in the patients without MetS (MBR-Tissue MetS (+) versus MetS (−): 9.7 ± 1.9 versus 11.0 ± 2.0, P = 0.003; MBR-All: 16.4 ± 4.0 versus 18.7 ± 3.6, P = 0.01; MBR-Choroid: 5.4 ± 1.4 versus 6.3 ± 2.0, P = 0.04; and BOS-Choroid: 67.4 ± 9.7 versus 71.8 ± 7.6, P = 0.03). Figure 4() represents comparison of MBR-Tissue and BOS-Choroid between patients with MetS and those without MetS. Table 3 shows the results of the single-regression analysis between MetS components and MBR, BOS, and BOT in the section of Tissue, Vessel, All, and Choroid. MBR-Tissue (r = −0.35, P = 0.002), MBR-All (r = −0.32, P = 0.005), MBR-Choroid (r = −0.27, P = 0.03), and BOS-Choroid (r = −0.27, P = 0.02) were significantly negatively correlated with the MetS components. Next, we divided the MBR-Tissue which showed the strongest correlations with the MetS components into 4 sections (superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal), and Table 4 shows the results of the single-regression analysis between MetS components and these parameters. MBR-Tissues—superior (r = −0.29, P = 0.01), inferior (r = −0.31, P = 0.007), and temporal (r = −0.40, P = 0.0004)—were significantly negatively correlated with the overlap of MetS components. Table 5 shows the results of the multiple-regression analysis for factors contributing independently to MetS components; the explanatory variables were the parameters that were significantly different in patients with and without MetS and mean IMT. The ratio of men HOMA-IR, temporal side of MBR-Tissue, and BOS-Choroid were identified as factors contributing independently to the overlap of the components (men = 1, women = 0: standard regression coefficient = 0.45, t value = 4.79, P < 0.0001; HOMA-IR: standard regression coefficient = 0.31, t value = 3.03, P = 0.003; MBR-Tissue (temporal): standard regression coefficient = −0.24, t value = −2.63, P = 0.01; and BOS-Choroid: standard regression coefficient = −0.23, t value = −2.52, P = 0.01).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical variables between in patients with and without metabolic syndrome.

| MetS (+) n = 32 | MetS (−) n = 44 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 61.6 ± 11.0 | 62.3 ± 11.6 | 0.79† |

| Men : women | 28 : 4 | 27 : 17 | 0.02‡ |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.0 ± 3.6 | 24.1 ± 3.8 | 0.001† |

| SBP (mmHg) | 133.0 ± 18.4 | 128.1 ± 17.1 | 0.24† |

| DBP (mmHg) | 75.5 ± 11.0 | 70.5 ± 11.1 | 0.06† |

| Spherical refraction (D) | −0.93 ± 2.71 | −0.25 ± 2.33 | 0.25† |

| IOP (right: mmHg) | 12.9 ± 2.9 | 12.4 ± 3.2 | 0.45† |

| OPP (mmHg) | 50.2 ± 8.4 | 47.4 ± 8.2 | 0.16† |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 69.8 ± 9.7 | 66.3 ± 9.2 | 0.12† |

| Mean IMT (mm) | 1.18 ± 1.44 | 0.88 ± 0.21 | 0.18† |

| e' velocity (cm/s) | 6.1 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 0.20† |

| E/e' ratio | 13.0 ± 4.7 | 11.0 ± 2.9 | 0.03† |

| Hypertension (%) | 26 (81.3) | 18 (40.9) | 0.001‡ |

| Diabetes (%) | 16 (50.0) | 4 (9.1) | 0.0001‡ |

| FBS (mg/dl) | 120.8 ± 29.8 | 94.9 ± 11.2 | <0.0001† |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 191.5 ± 27.1 | 198.5 ± 29.6 | 0.30† |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 163.3 ± 69.5 | 123.7 ± 51.4 | 0.006† |

| HDL-C (mg/dl) | 49.8 ± 19.9 | 57.0 ± 14.2 | 0.07† |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 114.2 ± 25.2 | 115.8 ± 24.6 | 0.78† |

| HOMA-IR | 2.8 ± 2.6 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 0.002† |

| Hematocrit (%) | 42.3 ± 4.3 | 40.8 ± 3.9 | 0.13† |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.84 ± 0.14 | 0.83 ± 0.17 | 0.81† |

Mean ± standard deviation; †unpaired t-test; ‡Yates 2 × 2 chi-squared test. MetS: metabolic syndrome; BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; D: diopter; IOP: intraocular pressure; OPP: ocular perfusion pressure; IMT: intima-media thickness; FBS: fasting blood sugar; HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance.

Table 2.

Comparison of items of ocular circulation between patients with and without metabolic syndrome.

| MetS (+) n = 32 | MetS (−) n = 44 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBR-Tissue | 9.7 ± 1.9 | 11.0 ± 2.0 | 0.003 |

| MBR-Vessel | 32.5 ± 7.6 | 35.0 ± 7.3 | 0.15 |

| MBR-All | 16.4 ± 4.0 | 18.7 ± 3.6 | 0.01 |

| MBR-Choroid | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 2.0 | 0.04 |

| BOS-Tissue | 73.8 ± 8.2 | 74.5 ± 6.7 | 0.69 |

| BOS-Vessel | 77.8 ± 6.5 | 78.6 ± 5.3 | 0.54 |

| BOS-All | 76.2 ± 7.2 | 77.1 ± 5.7 | 0.55 |

| BOS-Choroid | 67.4 ± 9.7 | 71.8 ± 7.6 | 0.03 |

| BOT-Tissue | 46.1 ± 5.1 | 46.5 ± 4.3 | 0.77 |

| BOT-Vessel | 50.2 ± 4.0 | 51.1 ± 4.1 | 0.35 |

| BOT-All | 48.2 ± 4.0 | 47.4 ± 8.2 | 0.29 |

| BOT-Choroid | 43.8 ± 4.6 | 45.2 ± 3.9 | 0.17 |

Mean ± standard deviation; unpaired t-test. MetS: metabolic syndrome; MBR: mean blur rate; BOS: blowout score; BOT: blowout time.

Figure 4.

The value of blowout score- (BOS-) Choroid and mean blur rate- (MBR-) Tissue in the optic nerve head in the patients with and without metabolic syndrome. Statistical differences between groups were calculated by unpaired t-test.

Table 3.

Correlation coefficients of a single-regression analysis between items of ocular circulation and components of metabolic syndrome.

| Explanatory variables | MBR | BOS | BOT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | r | P | |

| Tissue | −0.35 | 0.002 | −0.03 | 0.78 | −0.001 | 0.99 |

| Vessel | −0.20 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.76 | −0.11 | 0.37 |

| All | −0.32 | 0.005 | −0.04 | 0.74 | −0.12 | 0.31 |

| Choroid | −0.24 | 0.03 | −0.27 | 0.02 | −0.14 | 0.24 |

Objective variables: components of metabolic syndrome (0, 1, 2, and 3). n = 76. MBR: mean blur rate; BOS: blowout score; BOT: blowout time.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients of a single-regression analysis between 4 quadrants (superior, nasal, inferior, and temporal) of mean blur rate- (MBR-) Tissue and components of metabolic syndrome.

| Explanatory variables | r | P |

|---|---|---|

| MBR-Tissue (superior) | −0.29 | 0.01 |

| MBR-Tissue (nasal) | −0.20 | 0.08 |

| MBR-Tissue (inferior) | −0.31 | 0.007 |

| MBR-Tissue (temporal) | −0.40 | 0.0004 |

Objective variables: components of metabolic syndrome (0, 1, 2, and 3). n = 76.

Table 5.

Results of a multiple-regression analysis for factors independently contributing to components of metabolic syndrome.

| Explanatory variables | Standard regression | t value | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men = 1, women = 0 | 0.45 | 4.79 | <0.0001 |

| HOMA-IR | 0.31 | 3.03 | 0.003 |

| MBR-Tissue (temporal) | −0.24 | −2.63 | 0.01 |

| BOS-Choroid | −0.23 | −2.52 | 0.01 |

| E/e' ratio | 0.14 | 1.59 | 0.12 |

| BMI | 0.13 | 1.35 | 0.18 |

| Mean IMT | 0.10 | 1.14 | 0.26 |

Objective variables: components of metabolic syndrome (0, 1, 2, and 3). n = 76, R = 0.71, P < 0.0001. HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; MBR: mean blur rate; BOS: blowout score; BMI: body mass index; IMT: intima-media thickness.

The single-regression and multiple-regression analyses of factors independently contributing to the BOS-Choroid and MBR-Tissue (temporal) are shown in Tables 6 and 7. The MBR-Choroid was significantly correlated with age (r = −0.45, P < 0.0001), heart rate (r = 0.28, P = 0.01), hematocrit (r = 0.30, P = 0.009), and MetS components (r = −0.27, P = 0.02). And age (standard regression coefficient = −0.41, t value = −3.47, P = 0.0009), heart rate (standard regression coefficient = 0.44, t value = 4.89, P < 0.0001), and MetS components (standard regression coefficient = −0.31, t value = −3.41, P = 0.001) were identified to be factors independently contributing to the BOS-Choroid. MBR-Tissue (temporal) was significantly correlated with heart rate (r = −0.25, P = 0.03), mean IMT (r = −0.28, P = 0.01), and MetS components (r = −0.40, P = 0.0004). And mean IMT (standard regression coefficient = −0.22, t value = −2.03, P = 0.046) and MetS components (standard regression coefficient = −0.31, t value = −2.84, P = 0.006) were identified to be factors independently contributing to the MBR-Tissue (temporal).

Table 6.

Results of a single-regression analysis and multiple-regression analysis for factors independently contributing to BOS-Choroid.

| Explanatory variables | Single regression | Multiple regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | Standard regression | t value | P | |

| Age | −0.45 | <0.0001 | −0.41 | −3.47 | 0.0009 |

| Men = 1, women = 0 | 0.16 | 0.17 | |||

| BMI | −0.05 | 0.67 | |||

| Spherical refraction | −0.13 | 0.27 | |||

| IOP | 0.04 | 0.77 | |||

| OPP | −0.001 | 0.99 | |||

| Heart rate | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.44 | 4.89 | <0.0001 |

| Mean IMT | −0.01 | 0.95 | |||

| e' velocity | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.88 |

| E/e' ratio | −0.24 | 0.04 | −0.19 | −1.83 | 0.07 |

| Total cholesterol | −0.03 | 0.78 | |||

| LDL-C | 0.03 | 0.80 | |||

| Hematocrit | 0.30 | 0.009 | 0.15 | 1.46 | 0.15 |

| Creatinine | 0.06 | 0.62 | |||

| MetS components (0, 1, 2, and 3) | −0.27 | 0.02 | −0.31 | −3.41 | 0.001 |

Objective variables: BOS-Choroid; r = 0.70, P < 0.0001. n = 76. BOS: blowout score; BMI: body mass index; IOP: intraocular pressure; OPP: ocular perfusion pressure; IMT: intima-media thickness; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; MetS: metabolic syndrome. The correlation coefficient did not show more than 0.6 among the all explanatory variables.

Table 7.

Results of a single-regression analysis and multiple-regression analysis for factors independently contributing to MBR-Tissue (temporal).

| Explanatory variables | Single regression | Multiple regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | Standard regression | t value | P | |

| Age | −0.10 | 0.39 | |||

| Men = 1, women = 0 | −0.07 | 0.53 | |||

| BMI | −0.17 | 0.15 | |||

| Spherical refraction | 0.01 | 0.90 | |||

| IOP | 0.06 | 0.59 | |||

| OPP | −0.14 | 0.22 | |||

| Heart rate | −0.25 | 0.03 | −0.20 | −1.87 | 0.07 |

| Mean IMT | −0.28 | 0.01 | −0.22 | −2.03 | 0.046 |

| e' velocity | 0.11 | 0.33 | |||

| E/e' ratio | −0.17 | 0.14 | |||

| Total cholesterol | 0.01 | 0.96 | |||

| LDL-C | −0.01 | 0.92 | |||

| HOMA-IR | −0.08 | 0.48 | |||

| Hematocrit | −0.05 | 0.70 | |||

| Creatinine | 0.14 | 0.22 | |||

| MetS components (0, 1, 2, and 3) | −0.40 | 0.0004 | −0.31 | −2.84 | 0.006 |

Objective variables: MBR-tissue (temporal); r = 0.48, P = 0.0002. n = 76. MBR: mean blur rate: blowout score; BMI: body mass index; IOP: intraocular pressure; OPP: ocular perfusion pressure; IMT: intima-media thickness; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA-IR: homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; MetS: metabolic syndrome. The correlation coefficient did not show more than 0.6 among the all explanatory variables.

4. Discussion

In this study, and definition by the Japanese Committee to Evaluate Diagnostic Standards for Metabolic Syndrome was used for the diagnosis of the association between MetS [33, 34] and ocular circulation in the ONH and choroid shown by LSFG.

There were several reported relationships between the MetS and ocular findings. It has been reported that subjects with more MetS components had higher IOP [36]. Another study reported that the overlap of MetS components were predictors of progression to late age-related macular degeneration [37]. As an important evidence, it was clarified that MetS components, hypertension, and impaired FBS were contributing to an increasing risk of normal-tension and open-angle glaucoma [38, 39]. However, to the best of our knowledge, it was still unknown whether the incidence of MetS and the overlap of the MetS components affect the ocular circulation, including ONH and choroid. The purpose of the present study was thus to elucidate whether the overlap of the MetS components is affecting the ocular circulation obtained from LSFG.

In the analysis for patient's characteristics of our study, age was not significant different between patients with MetS and those without MetS. On the other hand, the ratio of men in patients with MetS was significantly higher than the ratio of men in patients without MetS. The E/e' ratio in patients with MetS was significantly higher than that in patients without MetS. On the other hand, IOP was not significantly different between patients with MetS and those without MetS.

Our analysis of the relationship between LSFG measurements and MetS revealed that MBR-Tissue, MBR-All, MBR-Choroid, and BOS-Choroid in patients with MetS were significantly lower than those in patients without MetS. In addition, the single-regression analysis showed that MBR-Tissue, MBR-All, MBR-Choroid, and BOS-Choroid were significantly correlated with the overlap of the MetS components. Especially, MBR-Tissue has the strongest correlations with the components of MetS. It was reported that MBR-Tissue in the ONH was strongly correlated with capillary blood flow obtained from hydrogen gas clearance technique [40]. Therefore, the overlap of the MetS components may lead to a decrease of the capillary blood flow in the ONH. The BOS represent the changing of the MBR during the cardiac cycle; thus, our results show changing of the MBR in the choroidal area which is wider in parallel with the cumulation of the MetS components. Previous few researchers reported that patients with MetS were more likely to have microvascular changes, for example, arteriovenous nicking, focal arteriolar narrowing, enhanced arteriolar wall reflex, retinopathy, and smaller arteriolar diameter [41–43]. Thus, we think that further study will be needed to clarify relationships between hemodynamic change in the ONH and choroid and the morphological microvascular change due to MetS.

Next, we divided MBR-Tissue in the ONH into four sections (superior, temporal, inferior, and nasal). In the results, the temporal side of MBR-Tissue has strongest correlations with the overlap of the MetS components.

The multiple-regression analysis showed that the ratio of men, HOMA-IR, temporal side of MBR-Tissue, and BOS-Choroid were identified as factors contributing independently to the overlap of the MetS components, comparing them with IMT and left ventricular diastolic function. It is well known that there is a strong correlation between insulin resistance and MetS [44, 45]. It was suggested that the temporal side of MBR-Tissue and BOS-Choroid is more strongly correlated with MtS components than mean IMT and E/e' ratio which are reported as contributing factors for MetS.

Our single-regression and multiple-regression analyses revealed that the age, heart rate, and overlap of MetS components were identified as factors contributing independently to the BOS-Choroid. In addition, mean IMT and the overlap of the MetS components were also identified as factors contributing independently to the temporal side of MBR-Tissue. It was suggested that the overlap of MetS components is one of the important factors for defining the ocular circulation in the ONH and choroid.

Previous other studies have confirmed that the tissue area of MBR and pulse waveforms in the ONH were well associated with sensitivity of the visual field in patients with normal-tension glaucoma [46, 47]. From the point of view of ocular circulation, our finding may be important clues to understand the mechanism of the progression of open-angle glaucoma due to the incidence of MetS and the overlap of the MetS components. In addition, a previous population-based study reported that there was no evidence of an association between the MetS and retinopathy independent of diabetes status [48]. Conversely, our study clarified that the incidence of MetS and the overlap of the MetS components are significantly affecting the ONH and choroidal circulation, from the stage of the absence of retinopathy.

There are some major limitations in this study. First, our subjects of the current study included some patients with sleep apnea syndrome. The apnea-hypopnea index which is the major outcome of polysomnography did not correlate with BOS and MBR in each section of ONH and choroid (data not shown). Thus, we considered that the influence that sleep apnea had on the results of the current study was low. However, there may be a slight selection bias in this study. Second, we did not evaluate the visual field and peripapillary retinal nerve layer thickness using optical coherence tomography. Thus, a more detailed further evaluation will be needed to clarify the relationships between ocular circulation and open-angle glaucoma in patients with MetS. Third, the use of calcium channel blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin 2 receptor blocker was significantly higher in the MetS group. Because the current study was a cross-sectional study, the effect of these drugs was not able to be evaluated. A prospective study is needed to determine whether treatment of MetS components prevents decreases in the temporal side of MBR-Tissue and BOS-Choroid. Finally, the current results were obtained using relatively small sample sets. Clearly, further careful validation studies with more samples are needed to evaluate the effects of MetS on the ocular circulation as primary endpoints.

In conclusion, our study clarified that the incidence of MetS and the overlap of the MetS components are significantly affecting to the ONH and choroidal circulation obtained from LSFG.

Ethical Approval

The Institutional Review Board of Toho University Sakura Medical Center approved the study (nos. 2011-009 and 2010-012).

Consent

The authors started the research after obtaining informed consent from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors have no proprietary or financial interest in any aspect of this report. This study had no sponsorship or other support. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest. We had no statistical consultation or assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Sattar N., Gaw A., Scherbakova O., et al. Metabolic syndrome with and without C-reactive protein as a predictor of coronary heart disease and diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation. 2003;108:414–419. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000080897.52664.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander C. M., Landsman P. B., Teutsch S. M., Haffner S. M., Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) NCEP-defined metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and prevalence of coronary heart disease among NHANES III participants age 50 years and older. Diabetes. 2003;52:1210–1214. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isomaa B., Almgren P., Tuomi T., et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakka H. M., Laaksonen D. E., Lakka T. A., et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2709–2716. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matoba Y., Inoguchi T., Nasu S., et al. Optimal cut points of waist circumference for the clinical diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in the Japanese population. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:590–592. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hassinen M., Komulainen P., Lakka T. A., et al. Metabolic syndrome and the progression of carotid intima-media thickness in elderly women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:444–449. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallenfeldt K., Hulthe J., Fagerberg B. The metabolic syndrome in middle-aged men according to different definitions and related changes in carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT) during 3 years of follow-up. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2005;258:28–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iglseder B., Cip P., Malaimare L., Ladurner G., Paulweber B. The metabolic syndrome is a stronger risk factor for early carotid atherosclerosis in women than in men. Stroke. 2005;36:1212–1217. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000166196.31227.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scuteri A., Najjar S. S., Muller D. C., et al. Metabolic syndrome amplifies the ageassociated increases in vascular thickness and stiffness. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;43:1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hulthe J., Bokemark L., Wikstrand J., Fagerberg B. The metabolic syndrome, LDL particle size, and atherosclerosis: the atherosclerosis and insulin resistance (AIR) study. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2000;20:2140–2147. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.20.9.2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollex R. L., Al-Shali K. Z., House A. A., et al. Relationship of the metabolic syndrome to carotid ultrasound traits. Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 2006;4:p. 28. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-4-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masugata H., Senda S., Goda F., et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction as assessed by echocardiography in metabolic syndrome. Hypertension Research. 2006;29:897–903. doi: 10.1291/hypres.29.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo J. M., Park T. H., Lee D. Y., et al. Subclinical myocardial dysfunction in metabolic syndrome patients without hypertension. Journal of Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 2011;19:134–139. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2011.19.3.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de las Fuentes L., Brown A. L., Mathews S. J., et al. Metabolic syndrome is associated with abnormal left ventricular diastolic function independent of left ventricular mass. European Heart Journal. 2007;28:553–559. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontes-Carvalho R., Ladeiras-Lopes R., Bettencourt P., Leite-Moreira A., Azevedo A. Diastolic dysfunction in the diabetic continuum: association with insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2015;14:p. 4. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0168-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamaki Y., Araie M., Kawamoto E., Eguchi S., Fujii H. Non-contact, two-dimensional measurement of tissue circulation in choroid and optic nerve head using laser speckle phenomenon. Experimental Eye Research. 1995;60:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isono H., Kishi S., Kimura Y., Hagiwara N., Konishi N., Fujii H. Observation of choroidal circulation using index of erythrocytic velocity. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2003;121:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujii H. Visualisation of retinal blood flow by laser speckle flow-graphy. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 1994;32:302–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02512526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujii H. Medical Diagnostic Techniques and Procedures. New Delhi, India; London, UK: Narosa Publishing House; 2000. Laser speckle flowgraphy; pp. 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi H., Sugiyama T., Tokushige H., et al. Comparison of CCD-equipped laser speckle flowgraphy with hydrogen gas clearance method in the measurement of optic nerve head microcirculation in rabbits. Experimental Eye Research. 2013;108:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugiyama T. Basic technology and clinical applications of the updated model of laser speckle flowgraphy to ocular diseases. Photonics. 2014;1:220–234. doi: 10.3390/photonics1030220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiba T., Takahashi M., Hori Y., Maeno T. Pulse-wave analysis of optic nerve head circulation is significantly correlated with brachial-ankle pulse-wave velocity, carotid intima-media thickness, and age. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2012;250:1275–1281. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-1952-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiba T., Takahashi M., Hori Y., Maeno T., Shirai K. Optic nerve head circulation determined by pulse wave analysis is significantly correlated with cardio ankle vascular index, left ventricular diastolic function, and age. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 2012;19:999–1005. doi: 10.5551/jat.13631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rina M., Shiba T., Takahashi M., Hori Y., Maeno T. Pulse waveform analysis of optic nerve head circulation for predicting carotid atherosclerotic changes. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2015;253:2285–2291. doi: 10.1007/s00417-015-3123-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiba T., Takahashi M., Matsumoto T., Shirai K., Hori Y. Arterial stiffness shown by the cardio-ankle vascular index is an important contributor to optic nerve head microcirculation. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2017;255:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3521-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Leary D. H., Polak J. F., Kronmal R. A., Manolio T. A., Burke G. L., Wolfson S. K., Jr Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takiuchi S., Kamide K., Miwa Y., et al. Diagnostic value of carotid intima-media thickness and plaque score for predicting target organ damage in patients with essential hypertension. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2004;18:17–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagueh S. F., Appleton C. P., Gillebert T. C., et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. European Journal of Echocardiography. 2009;10:165–193. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jep007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S. H., Choi S., Chung W. J., et al. Tissue Doppler index, E/E’, and ischemic stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2008;271(1-2):148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ommen S. R., Nishimura R. A., Appleton C. P., et al. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: a comparative simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study. Circulation. 2000;102:1788–1794. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews D. R., Hosker J. P., Rudenski A. S., Naylor B. A., Treacher D. F., Turner R. C. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Definition and the diagnostic standard for metabolic syndrome. Committee to Evaluate Diagnostic Standards for Metabolic Syndrome. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;94:794–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teramoto T., Sasaki J., Ueshima H., et al. Metabolic syndrome. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 2008;15:1–5. doi: 10.5551/jat.e580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sugiyama T., Araie M., Riva C. E., Schmetterer L., Orgul S. Use of laser speckle flowgraphy in ocular blood flow research. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2010;88:723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiba C., Shiba T., Takahashi M., Matsumoto T., Hori Y. Relationship between glycosylated hemoglobin A1c and ocular circulation by laser speckle flowgraphy in patients with/without diabetes mellitus. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2016;254:1801–1809. doi: 10.1007/s00417-016-3437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh S. W., Lee S., Park C., Kim D. J. Elevated intraocular pressure is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2005;21:434–440. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim M., Jeoung J. W., Park K. H., Oh W. H., Choi H. J., Kim D. M. Metabolic syndrome as a risk factor in normal-tension glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2014;92:637–643. doi: 10.1111/aos.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman-Casey P. A., Talwar N., Nan B., Musch D. C., Stein J. D. The relationship between components of metabolic syndrome and open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1318–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghaem Maralani H., Tai B. C., Wong T. Y., et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2015;35:459–466. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aizawa N., Nitta F., Kunikata H., et al. Laser speckle and hydrogen gas clearance measurements of optic nerve circulation in albino and pigmented rabbits with or without optic disc atrophy. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2014;55:7991–7996. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao Y., Yang K., Wang F., et al. Associations between metabolic syndrome and syndrome components and retinal microvascular signs in a rural Chinese population: the Handan Eye Study. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2012;250:1755–1763. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong T. Y., Duncan B. B., Golden S. H., et al. Associations between the metabolic syndrome and retinal microvascular signs: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2004;45:2949–2954. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawasaki R., Tielsch J. M., Wang J. J., et al. The metabolic syndrome and retinal microvascular signs in a Japanese population: the Funagata study. The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2008;92:161–166. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.127449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reaven G. M. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeFronzo R. A., Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:173–194. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi W., Kunikata H., Omodaka K., et al. Correlation of papillomacular nerve fiber bundle thickness with central visual function in open-angle glaucoma. Journal of Ophthalmology. 2015;2015:460918–460916. doi: 10.1155/2015/460918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiga Y., Omodaka K., Kunikata H., et al. Waveform analysis of ocular blood flow and the early detection of normal tension glaucoma. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2013;54:7699–7706. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keenan J. D., Fan A. Z., Klein R. Retinopathy in nondiabetic persons with the metabolic syndrome: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009;147:934–944. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]