Abstract

Purpose

Online pharmacies sell medicine over the Internet and deliver them by mail. The main objective of this study is to explore the extent of use of online pharmacies in Saudi Arabia which will be useful for the scientific community and regulators.

Methods

An Arabic survey questionnaire was developed for this study. The questionnaire was distributed via email and social media. Four sections were created to cover the objectives: experience with online shopping in general, demographics, awareness of the existence and customer experiences of buying medicine online, and reasons for buying/not buying medicine online.

Results

A total of 633 responses were collected. Around 69% (437) of them were female and the majority (256, 40.4%) was in the age range 26–40. Only 23.1% (146) were aware of the existence of online pharmacies where 2.7% (17) of them had bought a medicine over the Internet and 15 (88.2%) respondents out of the 17 was satisfied with the process. Lack of awareness of the availability of such services was the main reason for not buying medicines online. Many respondents (263, 42.7%) were willing to try an online pharmacy, although majorities (243, 45.9%) were unable to differentiate between legal and illegal online pharmacies. The largest categories of products respondents were willing to buy them online were nonprescription medicines and cosmetics.

Conclusion

The popularity of purchasing medicines over the Internet is still low in Saudi Arabia. However, because the majority of respondents are willing to purchase medicines online, efforts should be made by the Saudi FDA to set regulations and monitor this activity.

Keywords: Online pharmacies, Saudi Arabia, Prescription medicine, Internet

1. Introduction

Online pharmacies are companies that sell medicines, including prescription-only medicines, over the Internet and deliver them by mail (Makinen et al., 2005). The first online pharmacy was started in the United States (US) in the late 1990s, and sold both nonprescription and prescription-only medicines (Orizio et al., 2011). In the US, around 3000 websites were selling prescription medicines in 2009. This had increased to more than 5000 in 2010, and continues to rise rapidly (MarkMonitor, 2011, National Association of Boards of Pharmacy Progress, 2010). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have a section on its website entitled “Buying Medicines Over the Internet” (Gallagher and Colaizzi, 2000). A comprehensive review of previous research on online pharmacy and their usage has been published in 2011showed that it is spreading continuously with partial regulation (Orizio et al., 2011). Policy regulations and individual health literacy are two main aspects that the authors recommend to improve this phenomenon. However, such information about the online purchase of medicine is not available in Saudi Arabia. Exploring Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) website gives little information about regulations on internet sale of products or pharmaceuticals in the country (SFDA website, 2016). A warning statement has been published in SFDA website in 2011 (SFDA website, 2011). Usually a release form has to be filled by those who order a medicine online and supply a list of documents including the prescription. It is important to understand how this service operates to ensure that appropriate regulations are put in place to monitor and control the online purchase of medicines and to prevent any risk of prescription-medicine abuse. The aim of the study is to explore the extent of purchasing medicine online in Saudi Arabia. Two main objectives will be sought; the first will be the existence of such phenomenon, the second will be the reasons behind the willingness to purchase/not purchase medicine online.

2. Methodology

2.1. Development of questionnaire

Previous research has addressed different aspects of online pharmacy. An Arabic-language questionnaire was built through different stages. A review of related literature was done first (Orizio et al., 2011, Mazar et al., 2012). Then two experts in pharmacy and medicine were asked to review the survey, following which a few amendments were made. Clarity of the questionnaire was examined by three pharmacists and three lay persons. A pilot study involving 10 subjects (pharmacists and lay persons) was undertaken to examine the final draft of the survey.

The survey was developed using the SurveyMonkey program and distributed randomly via email and social media such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Twitter, between June 2013 and March 2014. An introductory paragraph has been created which insure confidentiality and anonymity of data collection and analysis. It also contains a statement “I consent to participate in the study” which participant must click before proceeding to the first question. The target population was Saudi Arabian citizens and residents. The questionnaire is available upon request.

2.2. The questionnaire

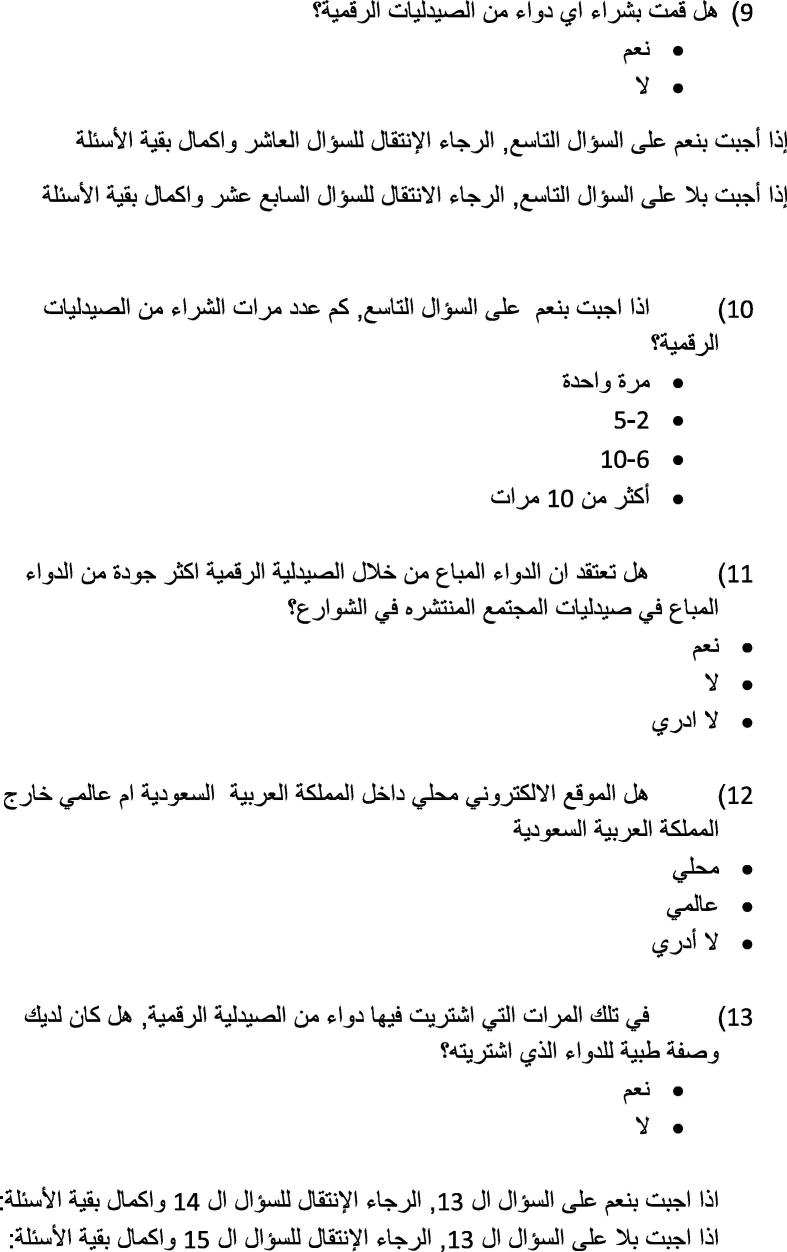

Four main sections were created. The first section consisted of three questions investigating the respondents’ experiences with online shopping. The second section collected demographic information including age, gender, education, and monthly salary. The third section included nine questions exploring the respondents’ experiences of buying medicines online. These questions covered the following topics:

-

•

Awareness of the existence of online pharmacies

-

•

Previous history of buying medicines online

-

•

Number of times buying medicines online

-

•

The quality of medicines bought over the Internet

-

•

Whether the website was local or international

-

•

Whether a prescription was obtained beforehand

-

•

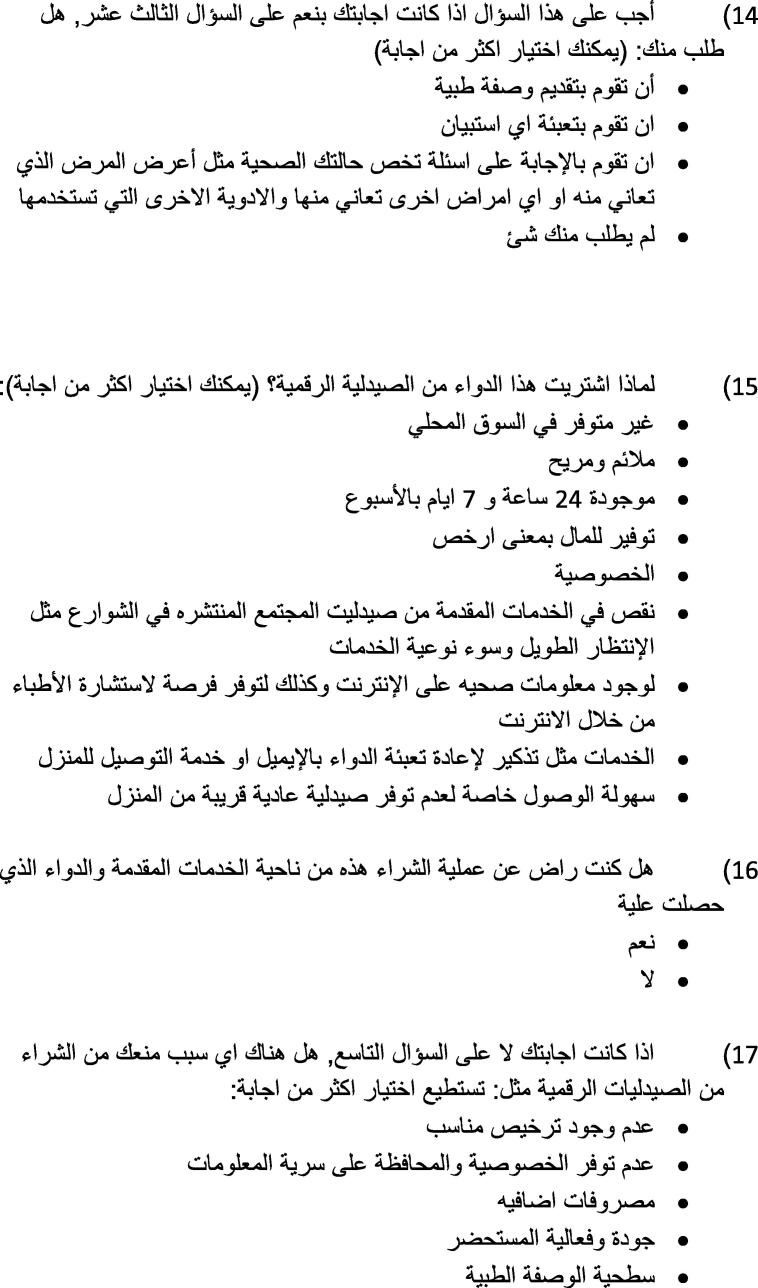

Whether they were asked to provide a prescription or complete a survey or answer a questionnaire about their health status

-

•

The reason for choosing to buy medicines online

-

•

The satisfaction level with this process.

Most of the response categories to the previous nine questions were in yes/no format. Other responses included specific statements such as reasons to buy medicine online.

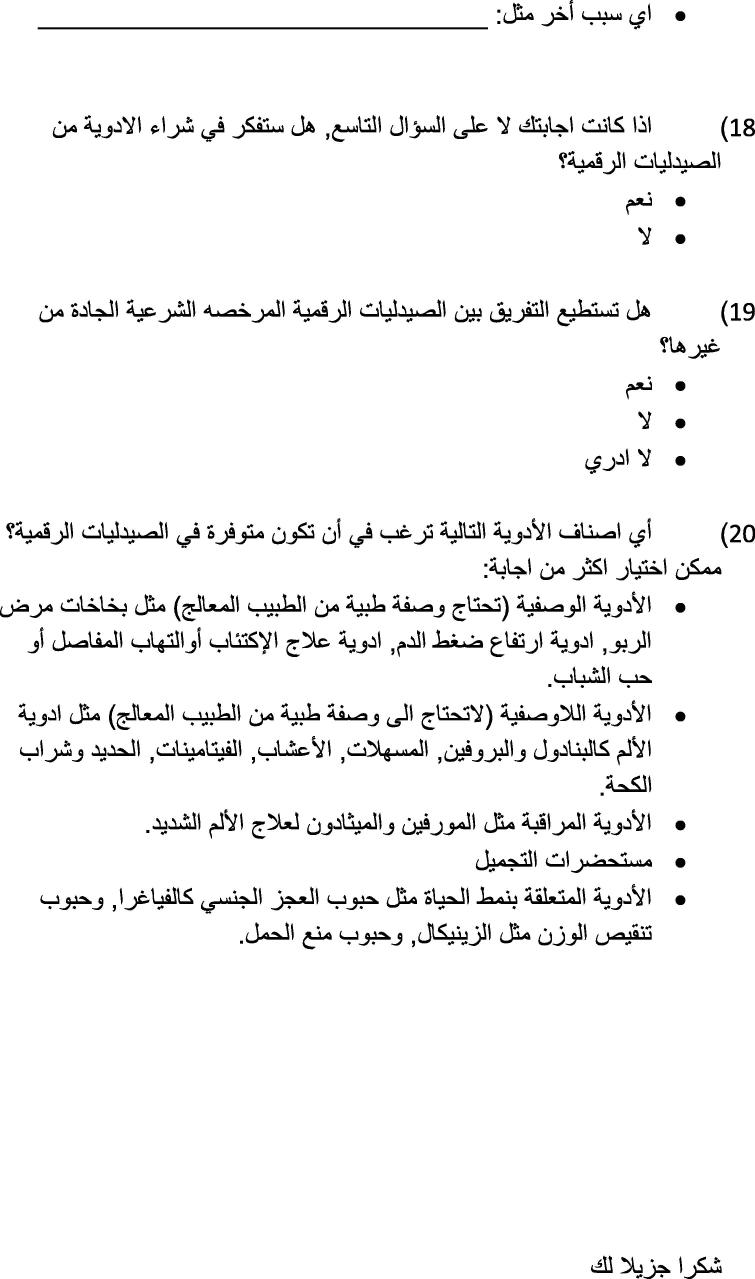

The final section investigated the reasons why respondents were unwilling to buy medicines online and whether or not they intended to purchase medicines online in the future. Two additional questions at the end of the questionnaire were asked, can you differentiate between legal and illegal online pharmacies and what categories of medicines they are willing to be available online.

2.3. Data analysis

The data were stored and analyzed using Excel 2010. Data are expressed as percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Participants characteristics

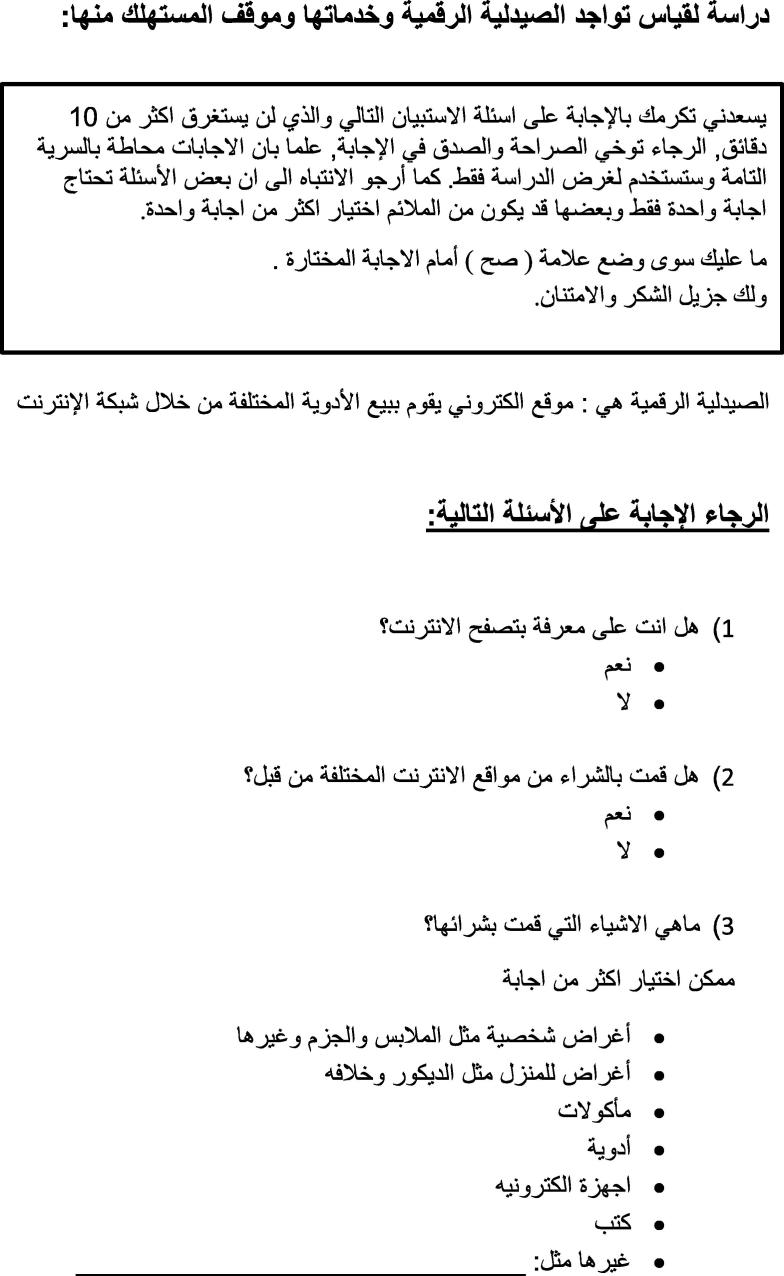

A total of 633 responses were collected. Of the respondents, 607 (95.9%) regularly browsed on the Internet. A significant number (428, 67.6%) of the respondents had tried to buy something online, of whom more than half (356, 56.6%) bought clothing or shoes. Items such as homewares (114, 18%), food (66, 10.5%), electronics (209, 33%), books (140, 22%), and medicines (17, 2.7%) were also purchased online. Around 69% (437) of the respondents were female. The majority (40.4%, 256) was in the age range 26–40 and more than 61% (390) had a bachelor’s degree. Surprisingly, 38% (242) of the respondents had no income. Table 1 shows the demographic details of the respondents.

Table 1.

Respondents’ demographics.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| N = 633 | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 437 (69) |

| Age (years old) | |

| Less than 18 | 31 (4.9) |

| 18–25 | 209 (33) |

| 26–40 | 256 (40.4) |

| 41–60 | 132 (20.9) |

| More than 60 | 5 (0.8) |

| Education | |

| Elementary | 3 (0.5) |

| Intermediate | 17 (2.7) |

| Secondary | 78 (12.3) |

| Diploma | 30 (4.7) |

| Bachelor | 390 (61.6) |

| Master | 79 (12.5) |

| PhD | 36 (5.7) |

| Monthly salary (US dollar) | |

| No salary | 242 (38.2) |

| Less than 1300 | 57 (9) |

| 1300–2600 | 121 (19.1) |

| 2601–3900 | 90 (14.2) |

| 3901–5200 | 51 (8.1) |

| 5201–6500 | 38 (6) |

| More than 6500 | 34 (5.4) |

3.2. Extent of use of online pharmacy

Only 23.1% (146) were aware of the existence of online pharmacies and only 2.7% (17) had bought medicines over the Internet.

Five respondents had tried to buy medicines online on one occasion, eight had tried 2–5 times, one had tried 6–10 times, and three had tried more than 10 times. The majority of the 17 respondents who had purchased medicines online (15, 88.2%) were satisfied with the process. Three (17.6%) believed that the medicines they bought from an online pharmacy were of better quality than those bought from a community pharmacy, while seven (41.2%) said that they were worse and 7 (41.2%) were unsure whether there was any difference. Almost all (16) of the respondents who had purchased medicines online indicated that the website was international, while only one person did not know where the website was located. Two of the 17 respondents (11.8%) said that they had a prescription for the medicines they purchased online. One had been asked to provide the prescription, while the other one had been asked to answer a number of questions regarding his/her health status.

3.3. Reasons for buying/not buying medicine online

Table 2 lists the reasons cited for buying medicines online. It can be seen that unavailability of the medicine locally was the most popular reason. Respondents who had not purchased any medicines online were asked to state the reason why they had not done so. The most commonly cited reason was a lack of awareness of online pharmacies (see Table 2 for other reasons). Other reasons were added as a free text; free texts were read and categorized by the author. A significant number of participants (142) did not answer this question.

Table 2.

Reasons for buying or not buying medicines online.

| Reason | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Reasons for buying medicines online: N = 17a | |

| Unavailable in local market | 8 (47) |

| Cheaper | 7 (41.2) |

| More convenient | 6 (35.3) |

| Good services such as home delivery and refill reminder by email | 4 (23.5) |

| Available 24 h, 7 day a week | 3 (17.6) |

| Providing health information and some consultation | 3 (17.6) |

| Easy delivery especially for those far from any community pharmacy | 3 (17.6) |

| More privacy | 2 (11.8) |

| Bad services of community pharmacy such as long waiting time | 1 (5.9) |

| Reasons for not buying medicines online: N = 457b | |

| No license | 116 (25.4) |

| Quality of the medicine | 85 (18.6) |

| Simple prescription | 62 (13.6) |

| Extra money | 45 (9.9) |

| No privacy and confidentiality | 21 (4.6) |

| Other reasons. N = 230c | 230 (50.3) |

| No idea about online pharmacy | 135 (58.7) |

| Medicines needed is available in community pharmacy | 55 (23.9) |

| No trust | 21 (9.1) |

| No interest | 9 (3.9) |

| No reason | 4 (1.7) |

| No answer | 4 (1.7) |

| Medicines available in hospitals | 2 (0.87) |

| Bad mail services | 2 (0.87) |

| Inappropriate storage | 2 (0.87) |

| Not allowed to enter Saudi Arabia | 2 (0.87) |

Total does not add up to 17 since respondents were asked to freely choose more than one reason.

Only 457 did answer this question, and respondents were asked to freely choose more than one reason.

Total does not add up to 230 since some respondents write more than one reason.

3.4. Future viewpoint of customers toward online pharmacy

Respondents were also asked whether they would consider purchasing medicines from an online pharmacy in the future, 42.7% (263) answered “Yes,” 38.5% (237) answered “No”, and 18.8% (116) did not answer this question. A very important question was whether respondents were able to differentiate between legal and illegal online pharmacies. Only 529 respondents answered this question, and the majority were either unable to differentiate between legal and illegal online pharmacies (243, 45.9%) or were unsure about their ability to differentiate (250, 47.3%) and the remaining 6.8% (36) were able to differentiate. Table 3 shows the most popular categories of products respondents (529, 83.6%) said they would like to be made available online.

Table 3.

Categories of medicines respondents were willing to be available onlinea.

| Category | (Number, %) N = 529a |

|---|---|

| Non-prescription medicines | (308, 58.2) |

| Cosmetics | (307, 58) |

| Prescription medicines | (113, 21.36) |

| Lifestyle medicines such as Viagra and birth control bills | (97, 18.34) |

| Narcotics | (30, 5.67) |

Only 529 subjects answer this question and respondents were asked to freely choose more than one answer.

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to explore the use of online pharmacy to purchase medicine among Saudi citizens. The results indicate that the online purchase of medicine is not yet popular. This study indicates that Internet browsing by young adults (below the age of 40) is common in Saudi Arabia. However, the frequency of attempts to buy medicines online is almost 3%. According to the literature, 4–6% of the US population purchased medicines online between 2003 and 2009 and this increased to 23% in 2012 (Fox, 2004, Baker et al., 2003, Cohen and Stussman, 2009, FDA BeSafeRx, 2016).

The satisfaction level was high among those who had purchased medicines online, similar high satisfaction levels have also been reported by other studies (Fox, 2004).

Medication quality was not a major concern among respondents; further research is needed to explore such important issue. The unavailability of medicines in the local market is considered a valid reason for people to seek alternative sources, and indicates the importance of online pharmacies for such customers. Convenience and cost savings were also among the most popular reasons for buying medicines online, similar to the US population (Fox, 2004).

One of the major concerns regarding the purchase of medicines online reported in literature is people obtaining prescription-only medicines without a prescription (Raine et al., 2008). This may increase public health risks in terms of nonmedical use of prescription medicines. Customers’ inability to provide a prescription and online medicine retailers’ failure to ask for a prescription opens up the possibility of illegal medicine sales over the Internet which needs further investigation that is beyond the scope of this study.

Interestingly, a good number of respondents who did not currently buy medicines online indicated that they are willing to buy medicines online in the future. This trend is likely to increase, and needs to be studied extensively and monitored. Very few respondents were able to recognize a legitimate online pharmacy. Attempts to increase customers’ awareness of and ability to identify legitimate online pharmacies have been made by many organizations, such as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, which has introduced a specific logo for registered online pharmacies (Goldenberg, 2011). However; this logo only applies to United kingdom-based websites. A review of the SFDA website found only a warning to buy medicine online in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the SFDA should focus on this issue to allow customers to clearly identify legitimate online pharmacies.

Nonprescription medicines were the most popular items among customers who are willing to buy online medicine. While narcotic is the least one. In US, studies have shown that around 3% of controlled prescription-medicine abusers purchase their medications online (Inciardi et al., 2010). However, the respondents in this survey may not have included people who are most likely to purchase controlled prescription medicines online. Therefore, efforts should be made to monitor attempts to purchase these medicines, and strict regulations should be enforced by online retailers to curb such behavior.

Although the extent of online purchase of medicine is limited in Saudi Arabia, efforts should be made to tighten the regulation of this service to ensure the safety and quality of medicines purchased from online pharmacies. If this market is not well regulated, the use of medicines that have not been approved by regulatory authorities or illegal versions of prescription medicines may increase. There have already been numerous reports documenting serious adverse effects or interactions following online medicine purchases (Cicero and Ellis, 2012, Mackey et al., 2013, Liang and Mackey, 2009).

Online sales of medicines, especially prescription only medicine, should be recognized as a serious and growing public health issue that requires a combination of legislative review, law enforcement, and public education. SFDA should consider adding a section to its website outlining the regulations regarding online purchase of medicines in Saudi Arabia to allow customers to do so legally.

One of the main limitations of this study is the small sample size, which does not cover all age groups in Saudi society. It is also an exploratory study so more deep investigation of this issue is needed. Future research should include a larger sample. It should include a correlation between customer characteristics and their online experience, attitudes and education with greater representation of the male gender to provide more accurate results.

5. Conclusions

The use of online pharmacies is not currently an issue in Saudi Arabia, because most people are unaware of the existence of online pharmacies. Problems such as registration issues and the quality of the products sold should be addressed prior to the widespread introduction of online pharmacies in Saudi Arabia.

Regulatory authorities and stakeholders could do much to encourage the safe use of online pharmacies, such as developing a logo to identify registered pharmacies and putting regulations in place to ensure the safety of the medicines that are sold.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest associated with this work.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by a grant from the “Research Center of the Female Scientific and Medical Colleges,” Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Appendix A. The questionnaire as appendix

References

- Baker L., Wagner T.H., Singer S., Bundorf M.K. Use of the Internet and e-mail for health care information: results from a national survey. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2400–2406. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2400. (May 14) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero T.J., Ellis M.S. Health outcomes in patients using no-prescription online pharmacies to purchase prescription drugs. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e174. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2236. (Eysenbach G, ed.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.A., Stussman, B., 2009 December 23. CDC/National Center for Health Statistics [cited 2015 October 28]. Webcite NCHS Health E-Stat: Health Information Technology Use Among Men and Women Aged 18–64: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2009 <http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/healthinfo2009/healthinfo2009.htm> (accessed 2016 May 28).

- FDA BeSafeRx: Know Your Online Pharmacy – Survey Highlights. Webcite <http://www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/buyingusingmedicinesafely/buyingmedicinesovertheinternet/besaferxknowyouronlinepharmacy/default.htm> (accessed 2016 May 28).

- Fox, S., 2004 October 10. Prescription Drugs Online. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project Webcite <http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2004/PIP_Prescription_Drugs_Online.pdf.pdf> (accessed 2016 May 28).

- Gallagher J.C., Colaizzi J.L. Issues in Internet pharmacy practice. Ann. Pharmacother. 2000;34(12):1483–1485. doi: 10.1345/aph.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg S.D. Use of online pharmacies to obtain antimicrobials without valid prescription. Q. J. Med. 2011;104:629–630. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi J.A., Surratt H.L., Cicero T.J. Prescription drugs purchased through the Internet: who are the end users? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110(1–2):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B.A., Mackey T. Searching for safety: addressing search engine, website, and provider accountability for illicit online drug sales. Am. J. Law Med. 2009;35(1):125–184. doi: 10.1177/009885880903500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey T.K., Liang B.A., Strathdee S.A. Digital social media, youth, and nonmedical use of prescription drugs: the need for reform. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15(7):e143. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2464. (Eysenbach G, ed.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinen M.M., Rautava P.T., Forsstrom J.J. Do OPs fit European internal markets? Health Policy. 2005;72:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MarkMonitor Press Release MarkMonitor, 2011. Webcite MarkMonitor Finds Online Drug Brand Abuse is Growing. <http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20090928005234/en/MarkMonitor-Finds-Online-Drug-Brand-Abuse-Growing> (accessed 2016 May 28).

- Mazar M., DeRoos F., Shofer F., Hollander J., McCusker C., Peacock N., Perrone J. Medications from the web: use of online pharmacies by emergency department patients. J. Emerg. Med. 2012;42(2):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Boards of Pharmacy Progress (NABP) Report for State and Federal Regulators, April 2010. Webcite Internet Drug Outlet Identification Program. <http://www.nabp.net/news/assets/InternetReport1-11.pdf> (Cited 2015 October 28).

- Orizio G., Merla A., Schulz P.J., Gelatti U. Quality of online pharmacies and websites selling prescription drugs: a systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e74. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine C., Webb D., Maxwell S. The availability of prescription-only analgesics purchased from the internet in the UK. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008;67(2):250–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA). Website <http://www.sfda.gov.sa/En/Pages/default.aspx> (cited December 2016).

- SFDA Warns about Purchasing Drugs via the Internet, October 2011. Website <http://www.sfda.gov.sa/en/news/Pages/homenews22-10-2011-a1.aspx> (cited December 2016).