Abstract

Optimal management of patients with thyroid cancer requires the use of sensitive and specific biomarkers. For early diagnosis and effective follow-up, the currently available cytological and serum biomarkers, thyroglobulin and calcitonin, present severe limitations. Research on microRNA expression in thyroid tumors is providing new insights for the development of novel biomarkers that can be used to diagnose thyroid cancer and optimize its management. In this review, we will examine some of the methods commonly used to detect and quantify microRNA in biospecimens from patients with thyroid tumor, as well as the potential applications of these techniques for developing microRNA-based biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of thyroid cancers.

1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer is the most frequently diagnosed endocrine malignancy, and its prevalence has increased markedly over the last decade [1]. Neoplastic transformation can occur in either the follicular or parafollicular cells of the gland. In the former case, the results range from differentiated tumors—papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTCs), follicular thyroid carcinomas (FTCs), and Hürthle cell carcinomas—to the rarer poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid carcinomas (PDTCs and ATCs, resp.). Transformation of the parafollicular cells produces medullary thyroid carcinomas (MTCs). Approximately, a percentage of MTCs are familial, and this category includes those diagnosed as part of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 syndrome [2]. Approximately, 80% of all differentiated thyroid carcinomas (DTCs) are PTCs. These tumors have a very good prognosis, thanks to the available tool (cytological examination of fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB)) which allows an early diagnosis and the efficacy of the current treatment. It involves surgery and radioactive iodine to eliminate residual and/or locoregionally recurrent disease and, in some cases, also distant metastases. This approach is not an option for patients with MTCs or for those whose tumors (PDTCs and ATCs for the most part) are no longer able to concentrate iodine. This defect is the result of impaired expression/function of the sodium/iodine symporter (NIS) or thyroperoxidase (TPO) caused by oncogene-activated signaling that leads to thyrocyte dedifferentiation [3–5]. For these tumors, novel therapeutic strategies are being actively investigated [6, 7].

For many years, assays of serum thyroglobulin and calcitonin levels have played important roles in the diagnosis and follow-up of thyroid cancer [8, 9]. Thyroglobulin is produced exclusively by follicular thyroid cells. In patients with DTC who have undergone total thyroidectomy and radioiodine remnant ablation, its presence in the serum is thus considered a marker of persistent or recurrent disease (locoregional or at distant site metastases) [10]. Calcitonin, a product of the parafollicular C-cells, serves a similar purpose in the follow-up of patients operated on for MTC [11]. Both markers, however, have several well-documented limitations involving specificity and sensitivity [11, 12], and with the increasing prevalence of thyroid malignancy, the need for noninvasive thyroid cancer biomarkers with higher accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity has become more pressing. Interest in this field has been sparked by our increasing understanding of the expression of microRNAs (miRNAs) in patients with thyroid tumors [13]. In this review, we will examine the growing body of evidence supporting the use of these small, noncoding RNA species to diagnose and predict the behavior of thyroid cancers, as well as the techniques currently used to detect and quantify their presence in tissues and other biological samples.

2. miRNAs in Thyroid Cancer

miRNAs are endogenous, noncoding RNAs with lengths ranging from 19 to 25 nucleotides. They play major roles in the posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression [14–16]. In general, miRNAs downmodulate the expression of a target gene by diminishing the stability of its transcript and/or inhibiting its translation [14–16]. By reducing the abundance of specific proteins in this manner, miRNAs exert fundamental modulatory effects on many physiological processes, including those involved in pre- and postnatal developments. Therefore, it is not surprising that their dysregulated expression is a feature of several pathological conditions, including neoplastic disease [17–20]. The first description of a link between aberrant miRNA expression and cancer was published in 2002 [21]. Since then, the number of miRNAs known to be encoded by the human genome has grown rapidly. A recent look at the miRBase database revealed over 2000 annotated human miRNAs [22], and their numbers are expected to increase [23].

The first published information on the role of miRNAs in thyroid tumorigenesis emerged in 2005 [24] and was followed by several other studies focusing on this issue. Thyroid tumors (and other cancers as well) display alterations involving various components of the machinery responsible for the complex process of miRNA biogenesis. Downregulated transcription of DICER has recently been observed in malignant thyroid tissues and cell lines, as compared with normal thyroid tissues and benign thyroid neoplasms, and this alteration was correlated with features indicative of tumor aggressiveness (extrathyroidal extension, lymph node and distant metastases, and recurrence) and with the presence of the BRAFV600E mutation [25]. A large cohort study of MTCs found that tumors harboring RET mutations exhibited upregulated expression of certain genes involved in miRNA biogenesis, as compared with their RET-wildtype counterparts, while no significant differences were observed between the expression levels of these genes in RAS-mutant and RAS-wildtype MTCs [26].

Specific patterns of miRNA expression have also been identified in a large number of studies performed on thyroid carcinomas [21, 27–30], and several miRNAs were found overexpressed or downregulated in major types of thyroid tumors [13, 31, 32]. Recent meta-analyses have attempted to provide a clearer overview of the miRNAs most commonly dysregulated in specific thyroid cancer histotypes. Several groups have reported overexpression of miRNA-146b, miRNA-221, miRNA-222, and miRNA-181b in PTCs, as compared with levels in normal thyroid tissues, and this upregulation is positively correlated with tumor aggressiveness [33–37]. Three of these four miRNAs, miRNA-146b, miRNA-221, and miRNA-222, are also upregulated in FTC, Hürthle cell thyroid carcinomas, and ATC [38–40]. In contrast, miRNA-197 and miRNA-346 are upregulated specifically in FTC [29, 41]. Members of the miRNA-17-92 cluster are highly expressed in ATC, as they are in other aggressive cancers [39], suggesting that dysregulation of this miRNA cluster influences the oncogenic process. Of note, increased expression of miRNAs-21, miRNA-183, and miRNA-375 has been associated with persistent and metastatic disease in MTC patients [42]. miRNA downregulations appear to be more variably associated with specific types of thyroid cancer. An exception is the downregulated expression of miRNAs belonging to the miRNA-200 and miRNA-30 families, which is associated exclusively with ATCs and is therefore suspected to play key roles in the acquisition of particularly aggressive tumor phenotypes [13, 39]. Table 1 shows the main miRNA dysregulations found in thyroid tumors, together with their documented associations with oncogenic mutations and their validated molecular targets. Among the latter, a functional role in oncogenic transformation of thyroid cancer cells is played by proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), NF-kB, programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), and yes-associated protein (YAP) (see Table 1), all involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and survival.

Table 1.

Known targets for deregulated miRNAs in thyroid tumors and association with genetic alterations.

| Histotype | miRNA expression (↑/↓)∗ | Oncogenic alteration | Molecular target | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTC | ↑ 146b, 221, 222 | n. d. | KIT | [24] |

| ↑ 181b, 221, 222 | n. d. | n. d. | [43] | |

| ↑ 187 | RET/PTC, RAS | n. d. | [27] | |

| ↑ 146b, 221, 222; ↓ 187 | BRAF V600E | |||

| ↑ 146b | BRAF V600E | n. d. | [33] | |

| ↑ 221 | BRAF V600E | n. d. | [34] | |

| ∗∗ | ↑ 451 | n.d. | n.d. | [44] |

| ↓ 137 | n. d. | CXCL12 | [45] | |

| ↓ 451a | n.d. | n.d. | [46] | |

| FTC | ↑ 197, 346 | n. d. | n. d. | [42] |

| ↑ 181b, 187 | n. d. | n. d. | [27] | |

| ↑ 221 | n. d. | n. d. | [29] | |

| ↓ 574-3p | ||||

| ↑ 146b, 183, 221 | n. d. | n. d. | [38] | |

| ↓ 199b | ||||

| ↓ 199a-5p | n. d. | CTGF | [47] | |

| Hürtle | ↑ 187, 197 | n. d. | n. d. | [27] |

| ↑ 885-5p | n. d. | n. d. | [29] | |

| ↑ 885-5p | n. d. | n. d. | [40] | |

| ↓ 138, 768-3p | ||||

| ATC | ↑ 137, 205, 302c | n. d. | n. d. | [27] |

| ↑ 221, 222 | n. d. | n. d. | [48] | |

| ↑ 146a | n. d. | NF-kB | [49] | |

| ↓ 30, 200 | n. d. | n. d. | [39] | |

| MTC | ↑ 130a, 138, 193a-3p, 373, 498 | n. d. | n. d. | [50] |

| ↓7, 10a,29c, 200b-200c | ||||

| ↑ 9, 21, 127, 154, 183, 224, 323, 370, 375 | n. d. | PDCD4 | [28, 51] | |

| ↓ 129-5p | RET | n. d. | [30] | |

| ↑ 183, 375 | n. d. | n. d. | [52] | |

| ↑ 10a, 375 | n.d. | YAP | [53] | |

| ↓455 |

(∗) ↑/↓: upregulated/downregulated; (∗∗): PTC with lymph node metastasis. ATC: anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; BRAF: b-type rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; CXCL12: C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12; FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma; KIT: proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase; MTC: medullary thyroid carcinoma; n. d.: not determined; PDCD4: programmed cell death 4; PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma; RAS: rat sarcoma; RET/PTC: rearranged during transfection/papillary thyroid carcinoma; YAP: yes-associated protein.

3. miRNA Detection in Biological Samples

miRNA expression patterns can be rich sources of biological information. Analysis of variations in these patterns can provide clues as to how different cellular processes are modulated under both physiological and pathological conditions [54]. Various diseases are associated with significant changes in the miRNA profile of involved tissues, and most of these changes have been reported in different kinds of cancer [55]. miRNAs display good stability in a variety of human biospecimens, including cell lines, fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed tissues, FNAB, blood plasma and serum, and urine [56]. Moreover, their levels provide more immediate and also more specific information on current physiological and pathological conditions than other molecules in these specimens [57]. Their importance in the modulation of gene expression and their remarkable stability in human biospecimens have led to develop a variety of approaches, and platforms have been developed to isolate and study miRNA expression, with the aim to identify profiles or single miRNAs associated with specific pathological condition.

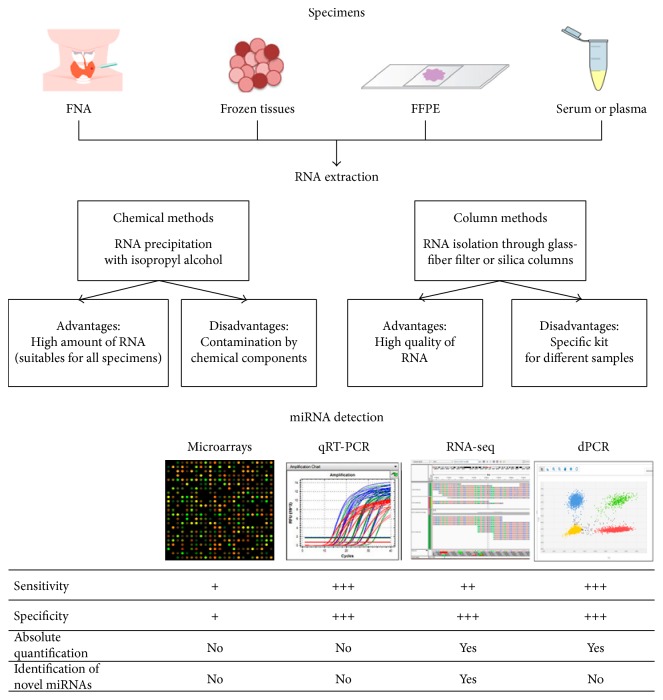

miRNA profiling begins with the isolation of total RNA. The extraction protocols used for this purpose are often slightly modified to enrich the fraction containing miRNAs and other small RNA species. Widely used methods for miRNA extraction fall into two main categories: chemical methods and column-based methods. The principal advantages and disadvantages of each are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

miRNA detection workflow. miRNAs can be isolated from different biospecimens. To isolate miRNAs, widely used methods are chemical and column-based techniques. After quantification step, samples are ready for miRNA profiling. Among widely used techniques, there are four established methods: microarray, quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR), massive parallel sequencing (RNA-seq), and digital PCR (dPCR). The sensitivity and specificity are classified as follows: + (low), ++ (moderate), +++ (high). FFPE: formalin-fixed paraffin embedded; FNA: fine-needle aspiration.

The isolated miRNA is then quantified and subjected to quality assessment. The quantity obtained is specimen specific, whereas the quality of the RNA depends on the extraction method used. The RNA is then ready for miRNA profiling. Four well-established methods are currently used to analyze miRNA expression: microarrays, quantitative reverse-transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), high-throughput sequencing (RNA-seq), and digital PCR (dPCR).

Microarray analysis was one of the first methods used for parallel analysis of large numbers of miRNAs. The miRNAs in a biological sample are labeled using fluorescent, chemical, or enzymatic techniques and then hybridized to DNA-based probes on the array. Microarray-based profiling allows rapid processing of the high number, and its cost is relatively low cost. However, it is the least sensitive and least specific of the miRNA profiling methods, and it does not allow the identification of novel targets [58].

QRT-PCR is probably the most popular method currently used for miRNA detection. It entails reverse transcription of miRNA to cDNA, followed by real-time monitoring of the accumulation of polymerase reaction products. Commercially available, customizable plates and microfluidic cards can be designed to examine a small set of miRNAs or to provide more comprehensive coverage. For qRT-PCR detection of hundreds of miRNAs, platforms are available with preplated PCR primers distributed across microfluidic cards containing nanoliter-scale wells. This approach is more specific and sensitive than microarray profiling. An internal control must be used for relative quantification of the expression; a standard curve can be used to obtain absolute quantification. Like microarray profiling, qRT-PCR cannot identify novel miRNAs [59].

RNA-seq is currently the most expensive technique for miRNA profiling, but it is also the most informative. It provides quantification data as well as sequence data and can therefore be used to identify novel miRNAs or sequence variations. A cDNA library of small RNAs is prepared from the samples of interest. This is followed by an adaptor ligation step and immobilization of the cDNA on a support (solid phase for solid-phase PCR, bead-based for emulsion PCR). These steps are followed by massively parallel sequencing of millions of cDNA molecules from the library. This approach allows simultaneous analysis of the expression patterns of a huge number of targets [60].

Digital PCR allows quantitative analysis of miRNA expression without internal controls. It is the most sensitive technique and the only one that can directly quantify miRNA in terms of absolute copy numbers. It involves the partitioning of a cDNA sample into multiple parallel PCR reactions. The reaction is performed with nanofluidics partitioning or emulsion chemistry, based on the random distribution of the sample on a specific support. It is superior to previously described methods in terms of sensitivity and precision, and it is the technique most widely used to study miRNA expression in plasma or serum samples, where there are no stable endogenous controls [61].

4. miRNAs as Diagnostic Markers in Thyroid Cancer

After clinical and ultrasound assessment of the likelihood of malignancy, most thyroid nodules are subjected to FNAB for cytological examination [62, 63]. This approach has shown good accuracy in discriminating most DTCs from benign lesions. However, in a nonnegligible proportion of cases, the cytology is indeterminate [10]. In these cases, the evaluation of molecular markers in the aspirate can often allow more confident presurgical differentiation of benign and malignant lesions. miRNAs are one of the novel classes of molecular markers that are being used to improve the diagnosis of thyroid cancer [13, 64]. Several studies have shown that a miRNA-based signature in FNABs can be used to discriminate benign from malignant thyroid nodules (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies of miRNAs in FNAB samples.

| Samples | Histological diagnosis∗ | miRNA expression (↑/↓)∗∗ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 (malignant) | PTC | ↑ 181b, 221, 222 | [43] |

| 62 (8 malignant, 5 benign, 49 n.d.) | 7 PTC, 1 Hürtle | ↑ 146b, 155, 187, 197, 221; 222, 224 | [27] |

| 115 (37 malignant, 78 benign) | 10 FTC or Hürtle (27 n.d.) | ↑ 138 | [65] |

| 27 (20 malignant, 7 benign) | PTC | ↑ 221 | [66] |

| 128 (88 malignant, 40 benign) | 3 ATC, 13 FTC, 72 PTC | ↑ 146b, 187, 221 | [67] |

| ↓ 30d | |||

| 141 (58 malignant, 83 benign) | 58 PTC | ↑ 146b, 155, 221 | [68] |

| 118 (70 malignant, 48 benign) | 70 PTC | ↑ 146b, 222 | [69] |

| 120 (45 malignant, 75 benign) | 1 FTC, 2 ATC, 4 MTC, 8 Hürtle, 30 PTC | ↑ 221, 222 | [70] |

| 44 (24 malignant, 20 benign) | 24 FTC | ↓ 148b-3p, 484 | [64] |

(∗) related to malign samples; (∗∗) ↑/↓: upregulated/downregulated. ATC: anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; FNAB: fine-needle aspiration biopsy; FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma; MTC: medullary thyroid carcinoma; PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma.

A recent meta-analysis [71] of 543 patients with benign (n = 277) or malignant (n = 266) thyroid nodules indicates that miRNA analysis of fine-needle aspirates (FNAs) allows significantly more accurate individuation of the malignant lesions than conventional cytology. More recently, Paskas et al. [70] assessed the performance of a panel of four markers, the BRAF V600E mutation, miRNA-221, miRNA-222, and galectin-3 protein, developing an algorithm for distinguishing benign and malignant thyroid nodules. In particular, among the 120 nodules of the study, the proposed algorithm classified 62 cases as benign (against the 75 cases observed with the conventional cytology classification), 9 false negative cases, and 6 false positive cases, with a sensitivity of 73.5%, a specificity of 89.8%, and an accuracy of 75.7%, thereby allowing over half the patient cohort to avoid unnecessary surgery. In a cohort of 118 samples of PTCs, Panebianco et al. [69] developed a statistical model that accurately differentiates malignant from benign indeterminate lesions on thyroid FNAs using a panel of two miRNAs and two genes (miRNA-146b, miRNA 222, KIT, and TC1). More recently, Stokowy et al. [64] have identified that two miRNA markers might improve the classification of mutation-negative thyroid nodules with indeterminate FNA. In this study, it was observed that miRNA-484 and miRNA-148b-3p identify thyroid malignancy with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 87% in a subset of 44 FNA samples.

As for ATCs, most of the studies conducted thus far have failed to produce statistically significant data since the number of tumor samples examined is invariably low [67, 72]. At present, no data are available on the potential of miRNA assays for diagnosis of MTC.

Recently, improved diagnosis of cancer has been achieved by assaying cancer-derived materials isolated from peripheral blood samples [73]. These “liquid biopsies” provide a genetic snapshot of the whole-tumor landscape, including both primary and metastatic lesions [74]. Relatively few reports are available on the expression and clinical significance of circulating miRNAs in patients with thyroid cancer, particularly those with less common tumors, such as MTC, PDTC, and ATC. As shown in Table 3, the studies published to date have focused mainly on patients with PTC, but the results are nonetheless characterized by high variability. Several elements can contribute to these highly variable results, including the number of patients of each study and/or sample-related factors (i.e., gender, sample collection time), preanalytical factors (i.e., sample type, storage conditions, and/or sample processing), and experiment-related factors (i.e., RNA extraction protocol, quantification methods). In addition, only few studies reported the isoforms of the miRNAs identified. Circulating levels of miRNA-146b-5p, miRNA-221-3p, and miRNA-222-3p in PTC patients have been found to be higher than those in healthy controls [75, 76, 84], while miRNA-222 and miRNA-146b levels also reportedly discriminate between PTCs and benign nodules [75, 80, 83]. Plasma levels of miRNA-21 in FTC patients are reportedly higher than those found in patients with benign nodules or PTC, whereas miRNA-181a is more highly expressed in PTC patients than in those with FTC [81]. In PTC patients, circulating levels of miRNA-146a-5p, miRNA-146b-5p, miRNA-221-3p, and miRNA-222-3p have been shown to decline after tumor excision [75, 76, 83, 84].

Table 3.

Circulating miRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers in thyroid carcinoma.

| Histotype | Sample type | miRNA | Up/downregulated | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTC | Serum | let-7e, 151-5p, 222 | Up | [75] |

| Plasma | 146b, 222 | Up | [76] | |

| Serum | 190 | Up | [77] | |

| 95 | Down | |||

| Plasma | hsa-let7b-5p, hsa-miR-10a-5p, hsa-miR-93-5p, hsa-miR-191 | Up | [78] | |

| hsa-miR-146a-5p, hsa-miR-150-5p, hsa-miR-199b-3p, has-miR-342-3p | Down | |||

| Plasma | let-7i, 25-3p, 140-3p, 451a | Up | [79] | |

| Plasma | 146b, 155 | Up | [80] | |

| Plasma-derived exosomes | 31-5p, 126-3p, 145-5p, 181a | Up | [81] | |

| Plasma | 9-3p, 124-3p | Up | [82] | |

| Serum | 222 | Up | [83] | |

| 21 | Down | |||

| Serum | 24-3p, 28-3p, 103a-3p, 146a-5p, 146b-5p, 191-5p, 221-3p, 222-3p | Up | [84] | |

| FTC | Plasma-derived exosomes | 21 | Up | [81] |

FTC: follicular thyroid carcinoma; PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma.

5. miRNAs as Prognostic Markers in Thyroid Cancer

miRNA profiling of thyroid cancers can also provide prognostic information useful for defining optimal management strategies. Recent studies have demonstrated that expression levels of certain miRNAs in thyroid tumor tissues are associated with clinic-pathological characteristics, such as tumor size, multifocality, capsular invasion, extrathyroidal extension, and both lymph node and distant metastases. Tumor size displays associations with tissue levels of miRNA-221, miRNA-222, miRNA-135b, miRNA-181b, miRNA-146a, and miRNA-146b [35, 85–87]. The latter two are also associated with multifocality [86, 87]. The single study that analyzed the association between miRNA expression and capsular or vascular invasion identified three miRNAs (miRNA-146b, miRNA-221, and miRNA-222), whose levels were significantly elevated in tumor tissue samples of PTC that had invaded vascular structures and/or the capsule. Extrathyroidal extension has been associated with higher levels of miRNA-221, miRNA-222, miRNA-146a, miRNA-146b, miRNA-199b-5p, and miRNA-135b [35, 87–89]. Expression levels of miRNA-221, miRNA-222, miRNA-21-3p, miRNA-146a, miRNA-146b, and miRNA-199b-5p are reportedly higher in patients with lymph node metastases [85, 86, 89, 90], and miRNA-146b and miRNA-221 are also associated with the presence of distant metastases [86]. Chou and coworkers showed that overall survival rates among patients with higher miRNA-146b expression levels are significantly decreased relative to those associated with lower tumor levels of this miRNA. Overexpression of miRNA-146b significantly increases cell proliferation, migration, and invasiveness and causes resistance to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis [91]. Higher levels of miRNA-146a, miRNA-146b, miRNA-221, and miRNA-222 display positive associations with higher TNM stage (III/IV versus I/II) [35, 85–87]. Risk of recurrence, defined according to the American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines, has been positively associated with higher expression of miRNA-146b-5p, miRNA-146b-3p, miRNA-21-5p, miRNA-221, miRNA-222-3p, miRNA-31-5p, miRNA-199a-3p/miRNA-199b-3p, miRNA-125b, and miRNA-203 and lower expression levels of miRNA-1179, miRNA-7-2-3p, miRNA-204-5p, miRNA-138, miRNA-30a, and let-7c [37, 92].

Notably, the studies and findings discussed above are related exclusively to PTCs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Tissue miRNAs as prognostic biomarkers in PTC.

| miRNA | Tumor size | Multifocality | Capsular invasion | Vascular invasion | ETE | LN metastases | Distant metastases | Overall survival | TNM stage | ATA risk | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1179 | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| 125b | ∗ | Geraldo and Kimura [92] | |||||||||

| 135b | ∗ | ∗ | Wang et al. [35] | ||||||||

| 138 | ∗ | Geraldo and Kimura [92] | |||||||||

| 146a | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Sun et al. [87] | ||||||

| 146b | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Wang et al. [35], Acibucu et al. [86], Sun et al. [87], Chou et al. [91], Geraldo and Kimura [92] |

| 146b-3p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| 146b-5p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| 181b | ∗ | Sun et al. [85] | |||||||||

| 199a-3p/199b-3p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||||

| 199b-5p | ∗ | ∗ | Peng et al. [89] | ||||||||

| 203 | ∗ | Geraldo and Kimura [92] | |||||||||

| 204-5p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| 21 | ∗ | Geraldo and Kimura [92] | |||||||||

| 21-3p | ∗ | Huang et al. [90] | |||||||||

| 21-5p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| 221 | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Wang et al. [35], Sun et al. [85], Acibucu et al. [86], Wang et al. [88], Geraldo and Kimura [92] | ||

| 222 | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | ∗ | Wang et al. [35], Sun et al. [85], Acibucu et al. [86], Wang et al. [88], Geraldo and Kimura [92] | |||

| 222-3p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| 30a | ∗ | Geraldo and Kimura [92] | |||||||||

| 31-5p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| 7–2-3p | ∗ | Rosignolo et al. [37] | |||||||||

| let-7c | ∗ | Geraldo and Kimura [92] |

∗: information included in indicated studies; ATA: American Thyroid Association; ETE: extrathyroidal extension; LN: lymph node.

Only two studies have investigated the role of miRNAs as prognostic markers in FTC and MTC [52, 93]. The study by Jikuzono and coworkers involved a comprehensive quantitative analysis of miRNA expression in tumor tissue from minimally invasive FTCs (MI-FTC) [93]. The subgroup of tumors that had metastasized (n = 12) exhibited significantly higher levels of miRNA-221-3p, miRNA-222-3p, miRNA-222-5p, miRNA-10b, and miRNA-92a than the nonmetastatic subgroup (n = 22). Expression of these miRNAs was also upregulated in widely invasive FTCs (WI-FTC; n = 13), which are characterized by distant metastasis and a worse prognosis. Logistic regression analysis identified one of these miRNAs, miRNA-10b, as a potential tool for predicting outcomes in cases of metastatic MI-FTC [93]. The second study, conducted by Abraham and coworkers, found that overexpression of miRNA-183 and miRNA-375 in MTCs (n = 45) was associated with lateral lymph node metastasis, residual disease, distant metastases, and mortality [52].

Recent studies have also looked at circulating miRNAs in patients with PTCs, which are showing undeniable promise as novel predictors of early disease relapse (Table 5).

Table 5.

Circulating miRNAs as prognostic biomarkers for PTC follow-up.

| Study | Number of cases | Samples | miRNA | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu et al. [75] | 9 | Pre- and postoperative serum (5–15 days) | 151-5p, 222 | Decreased after tumor excision |

| Lee et al. [76] | 32 | Pre- and postoperative plasma (2–6 weeks) | 221, 222, 146b | Decreased after tumor excision |

| Li et al. [79] | 7 | Pre- and postoperative plasma (4–7 days) | 25-3p, 451a | Decreased after tumor excision |

| Samsonov et al. [81] | 10 | Pre- and postoperative plasma-derived exosomes (7–10 days) | 126-3p, 145-5p, 146a-5p, 181a-5p, 206, 21-5p, 221-3p, 223-3p, 31-5p | Decreased after tumor excision |

| Yoruker et al. [83] | 31 | Pre- and postoperative serum (5 weeks) | 221, 222, 151-5p, 31 | Decreased after tumor excision |

| Rosignolo et al. [84] | 44 | Pre- and postoperative serum (30 days) | 146a-5p, 221-3p, 222-3p, 146b-5p, 28-3p, 103a-3p, 191-5p, 24-3p | Decreased after tumor excision |

PTC: papillary thyroid carcinoma.

In these patients, circulating levels of miRNA-146b-5p, miRNA-221-3p, miRNA-222-3p, and miRNA-146a-5p have been shown to decline after tumor excision [75, 76, 81, 83, 84]. Notably, serum levels of miRNA-221-3p and miRNA-146a-5p also appear to predict clinical responses to treatment, with significantly increased levels observed at the 2-year follow-up in PTC patients with structural evidence of disease, including some whose serum thyroglobulin assays remained persistently negative [84]. The association of thyroid cancer with circulating levels of miRNA-146b-5p, miRNA-221-3p, and miRNA-222-3p has been strengthened by evidence of their upregulated expression in PTC [37, 94], FTC [27, 95], and ATC [27] tissues and by their association with tumor aggressiveness.

6. Conclusion

Analysis of miRNA expression levels and detection of circulating miRNAs can be used for the early diagnosis of thyroid cancer and for monitoring treatment responses. Compared with circulating messenger RNAs, circulating miRNAs are emerging as more promising biomarker candidates because they are more stable and tissue specific. miRNAs can also be assessed in other biological samples, such as FNABs, which can be obtained with minimally invasive procedures to easily identify a specific profile, which makes specific miRNAs optimal diagnostic and/or prognostic biomarkers. Improved standardization of methods used to assay circulating miRNAs will allow more extensive use of this approach in defining individualized treatment strategies for thyroid cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

Writing support was provided by Marian Everett Kent, BSN (European Medical Writers Association). The authors thank Antonio Macrì and Domenico Saturnino (CNR-Institute of Neurological Sciences) for the administrative assistance during this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contributions

Marilena Celano and Francesca Rosignolo contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Kitahara C. M., Sosa J. A. The changing incidence of thyroid cancer. Nature Reviewes Endocrinology. 2016;12(11):646–653. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabanillas M. E., McFadden D. G., Durante C. Thyroid cancer. Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2783–2795. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlumberger M., Lacroix L., Russo D., Filetti S., Bidart J. M. Defects in iodide metabolism in thyroid cancer and implications for the follow-up and treatment of patients. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2007;3(3):260–269. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puxeddu E., Durante C., Avenia N., Filetti S., Russo D. Clinical implications of BRAF mutation in thyroid carcinoma. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;19(4):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xing M. Molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2013;13(3):184–199. doi: 10.1038/nrc3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulotta S., Celano M., Costante G., Russo D. Emerging strategies for managing differentiated thyroid cancers refractory to radioiodine. Endocrine. 2016;52:214–221. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ernani V., Kumar M., Chen A. Y., Owonikoko T. K. Systemic treatment and management approaches for medullary thyroid cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2016;50:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costante G., Durante C., Francis Z., Schlumberger M., Filetti S. Determination of calcitonin levels in C-cell disease: clinical interest and potential pitfalls. Nature Clinical Practice. Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009;5(1):35–44. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gianoukakis A. G. Thyroglobulin antibody status and differentiated thyroid cancer: what does it mean for prognosis and surveillance? Current Opinion in Oncology. 2015;27(1):26–32. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haugen B. R., Alexander E. K., Bible K. C., et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26(1):1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bae Y. J., Schaab M., Kratzsch J. Calcitonin as biomarker for the medullary thyroid carcinoma. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 2015;204:117–137. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22542-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Indrasena B. S. Use of thyroglobulin as a tumour marker. World Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2017;8(1):81–85. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v8.i1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boufraqech M., Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J., Kebebew E. MicroRNAs in the thyroid. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2016;30(5):603–619. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartel D. P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shukla G. C., Singh J., Barik S. MicroRNAs: processing, maturation, target recognition and regulatory functions. Molecular and Cellular Pharmacology. 2011;3(3):83–92. doi: 10.4255/mcpharmacol.11.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveto S., Mancino M., Manfrini N., Biffo S. Role of microRNAs in translation regulation and cancer. World Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2017;8(1):45–56. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v8.i1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294(5542):853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu J., Getz G., Miska E. A., et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435(7043):834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ardekani A. M., Naeini M. M. The role of MicroRNAs in human diseases. Avicenna Journal of Medical Biotechnology. 2010;2(4):161–179. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-748-8_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iorio M. V., Croce C. M. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation. Cancer Journal. 2012;18(3):215–222. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318250c001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calin G. A., Dumitru C. D., Shimizu M., et al. Frequent deletions and downregulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 a 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(24):15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozomara A., Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:D68–D73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Londin E., Loher P., Telonis A. G., et al. Analysis of 13 cell types reveals evidence for the expression of numerous novel primate- and tissue-specific microRNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(10):E1106–E1115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420955112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He H., Jazdzewski K., Li W., et al. The role of microRNA genes in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(52):19075–19080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509603102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erler P., Keutgen X. M., Crowley M. J., et al. Dicer expression and microRNA dysregulation associate with aggressive features in thyroid cancer. Surgery. 2014;156(6):1342–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puppin C., Durante C., Sponziello M., et al. Overexpression of genes involved in miRNA biogenesis in medullary thyroid carcinomas with RET mutation. Endocrine. 2014;47(2):528–536. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikiforova M. N., Tseng G. C., Steward D., Diorio D., Nikiforov Y. E. MicroRNA expression profiling of thyroid tumors: biological significance and diagnostic utility. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008;93(5):1600–1608. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mian C., Pennelli G., Fassan M., et al. MicroRNA profiles in familial and sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma: preliminary relationships with RET status and outcome. Thyroid. 2012;22(9):890–896. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dettmer M., Vogetseder A., Durso M. B., et al. MicroRNA expression array identifies novel diagnostic markers for conventional and oncocytic follicular thyroid carcinomas. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98(1):E1–E7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duan L., Hao X., Liu Z., Zhang Y., Zhang G. MiR-129-5p is down-regulated and involved in the growth, apoptosis and migration of medullary thyroid carcinoma cells through targeting RET. FEBS Letters. 2014;588(9):1644–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikiforova M. N., Chiosea S. I., Nikiforov Y. E. MicroRNA expression profiles in thyroid tumors. Endocrine Pathology. 2009;20(2):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s12022-009-9069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuziwara C. S., Kimura E. T. MicroRNAs in thyroid development, function and tumorigenesis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.12.017. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chou C. K., Chen R. F., Cho F. F., et al. miR-146b is highly expressed in adult papillary thyroid carcinomas with high risk features including extrathyroidal invasion and the BRAFV600E mutation. Thyroid. 2010;20(5):489–494. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y. L., Liu C., Dai X. X., Zhang X. H., Wang O. C. Overexpression of miR-221 is associated with aggressive clinicopathologic characteristics and the BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Medical Oncology. 2012;29(5):3360–3366. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z., Zhang H., He L., et al. Association between the expression of four upregulated miRNAs and extrathyroidal invasion in papillary thyroid carcinoma. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2013;6:281–287. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S43014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stokowy T., Gawel D., Wojtas B. Differences in miRNA and mRNA profile of papillary thyroid cancer variants. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2016;2016:10. doi: 10.1155/2016/1427042.1427042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosignolo F., Memeo L., Monzani F., et al. MicroRNA-based molecular classification of papillary thyroid carcinoma. International Journal of Oncology. 2017;50(5):1767–1777. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.3960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wojtas B., Ferraz C., Stokowy T., et al. Differential miRNA expression defines migration and reduced apoptosis in follicular thyroid carcinomas. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2014;388(1-2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuziwara C. S., Kimura E. T. MicroRNA deregulation in anaplastic thyroid cancer biology. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2014;2014:8. doi: 10.1155/2014/743450.743450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petric R., Gazic B., Goricar K., Dolzan V., Dzodic R., Besic N. Expression of miRNA and occurrence of distant metastases in patients with Hürthle cell carcinoma. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2016;2016:6. doi: 10.1155/2016/8945247.8945247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber F., Teresi R. E., Broelsch C. E., Frilling A., Eng C. A limited set of human microRNA is deregulated in follicular thyroid carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;91(9):3584–3591. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chu Y. H., Lloyd R. V. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: recent advances including microRNA expression. Endocrine Pathology. 2016;27(4):312–324. doi: 10.1007/s12022-016-9449-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pallante P., Visone R., Ferracin M., et al. MicroRNA deregulation in human thyroid papillary carcinomas. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2006;13(2):497–508. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z., Zhang H., Zhang P., Li J., Shan Z., Teng W. Upregulation of miR-2861 and miR-451 expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Medical Oncology. 2013;30(2):p. 577. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong S., Jin M., Li Y., Ren P., Liu J. miR-137 acts as a tumor suppressor in papillary thyroid carcinoma by targeting CXCL12. Oncology Reports. 2016;35(4):2151–2158. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minna E., Romeo P., Dugo M., et al. miR-451a is underexpressed and targets AKT/mTOR pathway in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(11):12731–12747. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun D., Han S., Liu C., et al. Microrna-199a-5p functions as a tumor suppressor via suppressing connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in follicular thyroid carcinoma. Medical Science Monitor. 2016;22:1210–1217. doi: 10.12659/MSM.895788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwertheim S., Sheu S., Worm K., Grabellus F., Schmid K. W. Analysis of deregulated miRNAs is helpful to distinguish poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma from papillary thyroid carcinoma. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2009;41(6):475–481. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pacifico F., Crescenzi E., Mellone S., et al. Nuclear factor-𝜅b contributes to anaplastic thyroid carcinomas through up-regulation of miR-146a. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(3):1421–1430. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santarpia L., Calin G. A., Adam L., et al. A miRNA signature associated with human metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2013;20(6):809–823. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pennelli G., Galuppini F., Barollo S., et al. The PDCD4/miR-21 pathway in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Human Pathology. 2015;46(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abraham D., Jackson N., Gundara J. S., et al. MicroRNA profiling of sporadic and hereditary medullary thyroid cancer identifies predictors of nodal metastasis, prognosis, and potential therapeutic targets. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17(14):4772–4781. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hudson J., Duncavage E., Tamburrino A., et al. Overexpression of miR-10a and miR-375 and downregulation of YAP1 in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2013;95(1):62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tay Y., Rinn J., Pandolfi P. P. The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature. 2014;505(7483):344–352. doi: 10.1038/nature12986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Leva G., Garofalo M., Croce C. MicroRNAs in cancer. Annual Review of Pathology. 2014;9:287–314. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Makarova J. A., Shkurnikov M. U., Wicklein D., et al. Intracellular and extracellular microRNA: an update on localization and biological role. Progress in Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2016;51(3-4):33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buitrago D. H., Patnaik S. K., Kadota K., Kannisto E., Jone D. R., Adusumilli P. S. Small RNA sequencing for profiling microRNAs in long-term preserved formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded non-small cell lung cancer tumor specimens. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hunt E. A., Broyles D., Head T., Deo S. K. MicroRNA detection: current technology and research strategies. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. 2015;8:217–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-071114-040343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moldovan L., Batte K. E., Trgovcich J., Wisler J., Marsh C. B., Piper M. Methodological challenges in utilizing miRNAs as circulating biomarkers. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2014;18(3):371–390. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pritchard C. C., Cheng H. H., Tewari M. MicroRNA profiling: approaches and considerations. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012;13(5):358–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huggett J. F., Whale A. Digital PCR as a novel technology and its potential implications for molecular diagnostics. Clinical Chemistry. 2013;59(12):1691–1693. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.214742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gharib H., Papini E., Paschke R., et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules. Endocrine Practice. 2010;16(1):1–43. doi: 10.4158/10024.GL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paschke R., Hegedus L., Alexander E., Valcavi R., Papini E., Gharib H. Thyroid nodule guidelines: agreement, disagreement and need for future research. Nature Reviews. Endocrinology. 2011;7(6):354–361. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stokowy T., Wojtas B., Jarzab B., et al. Two-miRNA classifiers differentiate mutation-negative follicular thyroid carcinomas and follicular thyroid adenomas in fine needle aspirations with high specificity. Endocrine. 2016;54(2):440–447. doi: 10.1007/s12020-016-1021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vriens M. R., Weng J., Suh I., et al. MicroRNA expression profiling is a potential diagnostic tool for thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2012;118(13):3426–3432. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mazeh H., Mizrahi I., Halle D., et al. Development of a microRNA-based molecular assay for the detection of papillary thyroid carcinoma in aspiration biopsy samples. Thyroid. 2011;21(2):111–118. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shen R., Liyanarachchi S., Li W., et al. MicroRNA signature in thyroid fine needle aspiration cytology applied to “atypia of undetermined significance” cases. Thyroid. 2012;22(1):9–16. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Agretti P., Ferrarini E., Rago T., et al. MicroRNA expression profile helps to distinguish benign nodules from papillary thyroid carcinomas starting from cells of fine-needle aspiration. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;167(3):393–400. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Panebianco F., Mazzanti C., Tomei S., et al. The combination of four molecular markers improves thyroid cancer cytologic diagnosis and patient management. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:p. 918. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1917-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paskas S., Jankovic J., Zivaljevic V., et al. Malignant risk stratification of thyroid FNA specimens with indeterminate cytology based on molecular testing. Cancer Cytopathology. 2015;123(8):471–479. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Y., Zhong Q., Chen X., Fang J., Huang Z. Diagnostic value of microRNAs in discriminating malignant thyroid nodules from benign ones on fine-needle aspiration samples. Tumour Biology. 2014;35(9):9343–9353. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Forte S., La Rosa C., Pecce V., Rosignolo F., Memeo L. The role of microRNAs in thyroid carcinomas. Anticancer Research. 2015;35(4):2037–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ilié M., Hofman P. Pros: can tissue biopsy be replaced by liquid biopsy? Translational Lung Cancer Research. 2016;5(4):420–423. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2016.08.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Larrea E., Sole C., Manterola L., et al. New concepts in cancer biomarkers: circulating miRNAs in liquid biopsies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016;17(5):p. 627. doi: 10.3390/ijms17050627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu S., Liu Y., Wang J., et al. Circulating microRNA profiles as potential biomarkers for diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97(6):2084–2092. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee J. C., Zhao J. T., Clifton-Bligh R. J., et al. MicroRNA-222 and MicroRNA-146b are tissue and circulating biomarkers of recurrent papillary thyroid cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4358–4365. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cantara S., Pilli T., Sebastiani G., et al. Circulating miRNA95 and miRNA190 are sensitive markers for the differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules in a Caucasian population. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2014;99(11):4190–4198. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Graham M. E., Hart R. D., Douglas S., et al. Serum microRNA profiling to distinguish papillary thyroid cancer from benign thyroid masses. Journal of Otolaryngology - Head & Neck Surgery. 2015;44(1):p. 33. doi: 10.1186/s40463-015-0083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li M., Song Q., Li H., Lou Y., Wang L. Circulating miR-25-3p and miR-451a may be potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of papillary thyroid carcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10(8, article e0135549) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee Y. S., Lim Y. S., Lee J. C., et al. Differential expression levels of plasma-derived miR-146b and miR-155 in papillary thyroid cancer. Oral Oncology. 2015;51(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Samsonov R., Burdakov V., Shtam T., et al. Plasma exosomal miR-21 and miR-181a differentiates follicular from papillary thyroid cancer. Tumour Biology. 2016;37(9):12011–12021. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yu S., Liu X., Zhang Y., et al. Circulating microRNA124-3p, microRNA9-3p and microRNA196b-5p may be potential signatures for differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules. Oncotarget. 2016;7(51):84165–84177. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yoruker E. E., Terzioglu D., Teksoz S., Uslu F. E., Gezer U., Dalay N. MicroRNA expression profiles in papillary thyroid carcinoma, benign thyroid nodules and healthy controls. Journal of Cancer. 2016;7(7):803–809. doi: 10.7150/jca.13898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rosignolo F., Sponziello M., Giacomelli L., et al. Identification of thyroid-associated serum microRNA profiles and their potential use in thyroid cancer follow-up. Journal of the Endocrine Society. 2017;1(1):3–13. doi: 10.1210/js.2016-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun Y., Yu S., Liu Y., Wang F., Liu Y., Xiao H. Expression of miRNAs in papillary thyroid carcinomas is associated with BRAF mutation and clinicopathological features in Chinese patients. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2013;2013:10. doi: 10.1155/2013/128735.128735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Acibucu F., Dökmetaś H. S., Tutar Y., Elagoz Ş., Kilicli F. Correlations between the expression levels of micro-RNA146b, 221, 222 and p27Kip1 protein mRNA and the clinicopathologic parameters in papillary thyroid cancers. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 2014;122:137–143. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1367025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sun M., Fang S., Li W., et al. Associations of miR-146a and miR-146b expression and clinical characteristics in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Biomarkers. 2015;15:33–40. doi: 10.3233/CBM-140431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang P., Meng W., Jin M., Xu L., Li E., Chen G. Increased expression of miR-221 and miR-222 in patients with thyroid carcinoma. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2012;11:2774–2781. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peng Y., Li C., Luo D. C., Ding J. W., Zhang W., Pan G. Expression profile and clinical significance of microRNAs in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Molecules. 2014;19:11586–11599. doi: 10.3390/molecules190811586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Huang Y., Liao D., Pan L., et al. Expressions of miRNAs in papillary thyroid carcinoma and their associations with the BRAFV600E mutation. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2013;168:675–681. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chou C. K., Yang K. D., Chou F. F., et al. Prognostic implications of miR-146b expression and its functional role in papillary thyroid carcinoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013;98:E196–E205. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Geraldo M. V., Kimura E. T. Integrated analysis of thyroid cancer public datasets reveals role of post-transcriptional regulation on tumor progression by targeting of immune system mediators. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jikuzono T., Kawamoto M., Yoshitake H., et al. The miR-221/222 cluster, miR-10b and miR-92a are highly upregulated in metastatic minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma. International Journal of Oncology. 2013;42:1858–1868. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159:676–690. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dettmer M., Perren A., Moch H., Komminoth P., Nikiforov Y. E., Nikiforova M. N. Comprehensive microRNA expression profiling identifies novel markers in follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2013;23:1383–1389. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]