Abstract

The purpose of this study was to explore the role of non-spousal family support on mental health among older, church-going African American men. The mixed methods objective was to employ a design that used existing qualitative and quantitative data to explore the interpretive context within which social and cultural experiences occur. Qualitative data (n=21) were used to build a conceptual model that was tested using quantitative data (n= 401). Confirmatory factor analysis indicated an inverse association between non-spousal family support and distress. The comparative fit index, Tucker-Lewis fit index, and root mean square error of approximation indicated good model fit. This study offers unique methodological approaches to using existing, complementary data sources to understand the health of African American men.

Keywords: African American men, church, non-spousal family support, mental health outcomes, mixed methods

As the use of mixed methods continues to grow, more disciplines are beginning to expand on how it can be used to achieve discipline-specific research goals and objectives (Curry & Nunez-Smith, 2015; Haight & Bidwell, 2015; Watkins & Gioia, 2015). The distinct characteristics and utility of mixed methods research in providing depth and breadth of a research topic is attractive to both novice and seasoned scholars. First, mixed methods involve the collection and analysis of qualitative and quantitative data in ways that are rigorous and epistemologically sound (Creswell, 2015; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Hesse-Biber, 2010; Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, 2007). Rigorous data collection and analysis refers to making data collection and analysis decisions that are thorough and based on a predetermined and tested system. Ensuring that the methods are epistemologically sound refers to data collection and analysis that are framed so that they help determine how we gain knowledge of what we know.

Mixed methods also involves the integration of qualitative and quantitative data in ways that underscore the advantages of using both research approaches to illuminate and advance our understanding of the topic of interest. Though it is sometimes difficult to locate studies where the methods are truly integrated, all mixed methods studies, by definition, imply some form of integration of the data (Bazeley, 2009; Creswell & Plano, 2011). Literature suggests that the type and level of integration are subject to continuing controversy (Creswell & Tashakkori, 2007). The current study relies on the premise and promise of mixed methods research as a way to examine the breadth and depth of non-spousal family support experiences of older, church-going African American men. Previous scholars have used mixed methods to understand various experiences of African American men including those of male athletes at historically black colleges and universities (Cooper & Hall, in press) and those of substance-abusing men who have sex with men (Buttram & Kurtz, 2015). However, no study to date has benefited from the use and integration of qualitative and quantitative data in order to understand the non-spousal family support experiences of church-going African American men, which is the aim of this study.

Findings from research on African American men’s mental health underscore the importance of understanding how social (e.g., interpersonal and intrapersonal relationships) and cultural experiences (e.g., familiarities associated with being both African American and male) influence their mental health status over the adult life course (Watkins, 2012a). Several lines of evidence suggest that early exposure to disadvantaged socioeconomic conditions adversely affects the mental health of African American males, increasing risk factors for the development of psychiatric mood disorders in adulthood (Caldwell, Antonakos, Tsuchiya, Assari, & De Loney, 2013; Ellis, Caldwell, Assari, & De Loney, 2014). Our own research and that of others finds that in addition to the social and economic hardships many African American men face, marginalized roles within their families, communities, and society at large, also restrict their ability to establish and maintain positive mental health and wellbeing as they age (Roy & Dyson, 2010; Watkins & Neighbors, 2012).

Disproportionately high unemployment and overrepresentation in low wage occupations – even among college educated African American men (Watkins, 2012a; Watkins & Neighbors, 2012) -- severely disadvantages access to material resources necessary to support one’s self, a partner and/or children. These disadvantages also create role strain between poor socioeconomic circumstances and the masculine social expectation for adult African American men to be providers for their families (Harris, 2013). When evaluating the adult life course of African American men, prior research reports that their mental health during middle adulthood is heavily influenced by work-related stress, interpersonal relationships, and decisions that impact their economic and social capital (Lincoln, Taylor, Watkins & Chatters, 2011; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011). However, life concerns that shape mental health trajectories for older African American men shift toward adjusting to and coping with functional limitations, health-related challenges, costs associated with aging, and life transitions related to leaving the workforce such as fixed incomes and social isolation (Watkins, 2012a).

While ample research has been developed around the differential receipt of mental health services between older African Americans and whites more broadly (Connor et al, 2010; Neighbors et al, 2008; Shellman, Granara & Rosengarten, 2011), we know surprisingly little about the social and cultural contexts of maintaining mental health throughout life transitions for older African American men specifically. Interpersonal and family relationships take on renewed importance as people age, and since older African American men are more likely than their younger counterparts to attend church where they might receive adjuvant mental health care (Taylor, Chatters & Jackson, 2007), a first step in this effort is understanding the non-spousal family support experienced by older African American men who attend church. The present study extends existing literature by attempting to contextualize how non-spousal family support influences mental health outcomes among older, church-going African American men.

Mental health and the black church

African American religious institutions have a long and varied history of providing lay mental health support for African American older adults, particularly those who live in communities underserved by formal mental health services (Chatters, Taylor, Woodward & Nicklett, 2015; Krause, 2006; Neighbors, Musick & Williams, 1998; Taylor et al, 2000). Many African Americans utilize faith communities, churches in particular, as a buffer for their mental health. Specifically, social support provided by a close-knit network of co-congregants is protective against psychological distress, independent of family-based social support (Chatters, et al., 2015). This experience may be gendered as African American women may thrive in the social culture of church, at least initially, easier than African American men. Thus, African American men may not be able to benefit from the advantages experienced from the social support, and thereby, improved mental health in the context of the black church compared to their female counterparts. These considerations imply that researchers and practitioners should be more deeply concerned with investigating the potential role of the church or faith-based community as a backdrop for reaching older African American men with resources that may attenuate poor mental health outcomes.

Family support for African American men

Research suggests that African American home life is broadly centered on a large network of kinship and family support (i.e., spouses or significant others, cousins, uncles, aunts, and close family friends) (White, 2004). The social support provided by these kinship networks may look characteristically different for some African Americans compared to whites. For example, a study by Rosenbarb, Bellack, and Aziz (2006) found that high levels of critically engaged behaviors by family members predicted better mental health outcomes for African Americans when compared to whites. Specifically, the authors identified fervent communication styles as a common cultural practice among many African American families because approaching a family member to address problematic health behavior is viewed as an expression of concern and care (Taylor, Forsythe-Brown, Taylor & Chatters, 2014). Thereby, one way to understand the association between health and family dynamics among African Americans is to explicitly link multiple inquiries about one’s health and well being to the degree to which he or she is concerned about that family member. A positive outcome would be for the family member in question to engage in healthy behaviors as a result of their family member’s concerns.

Studies have suggested that social support arising from strong family relationships has health-promoting effects for African American adults across a range of physical and mental health conditions including, but not limited to, the risk of suicide (Compton, Thompson & Kaslow, 2005), diabetes self-management (Tang, Brown, Funnel & Anderson, 2008), and cancer survivorship (Hamilton et al, 2010). For African American men specifically, marriage is an important source of health-enhancing support. In fact, a large body of evidence suggests that marriage is more psychologically beneficial for African American men than African American women (e.g., Sitgraves, 2008) such that separated and divorced African American men have higher rates of depression than their married counterparts. Further, relative rates of psychiatric disorder are higher in separated/divorced and never-married African American men compared to non-married African American women and their peers (Hurt, 2012; Sitgraves, 2008). Research characterizing the influence of familial support on health outcomes for African American men outside of spousal support is limited and mixed. However, what we know is that African American men use informal social support resources, such as family and friends, as buffers to reduce the effects of stress and distress on their mental health (Chatters, et al., 2015; Taylor, Chatters, & Jackson 1997; Pearlin 1999).

Rationale for the current study

Investigations into the social support networks of African American men and the impact of that support on physical and mental health outcomes have narrowly focused on socially marginalized men, such as those implanted in gang activity (Mac An Ghaill, 1994), the criminal justice system (Gaines, 2007), homelessness (Littrell & Beck, 2001) and low-income nonresidential fathers (Anderson, Kohler, & Letiecq, 2005). This shortcoming in the literature highlights the critical need to further examine how kinship and related social support can serve as a protective factor for the health and mental health of African American men. Similarly, the research on non-spousal family support for older African American men is limited, likely due to the short life expectancy of African American men compared to African American women, 71.8 vs. 78, respectively (Hoyert & Xu, 2012). Still lower than the life expectancy for white men (76.5), the life expectancy for African American men has seen modular increases over the years, suggesting a potential “healthy survivor effect” (Lincoln, et al., 2011; Watkins, et al., 2011) for those who are able to maintain good health and prevent disease. These gradual increases have not received much attention, though some scholars have examined facilitators that may not only increase life expectancy but also improve quality of life for African American men.

One facilitator that has had an important role in the development of healthy African American communities has been the role of the church in the African American community, also known as the “black church” (Dessio, Wade, Chao, Kronenberg, Cushman, & Kalmuss, 2004; Taylor & Chatters, 2011; Taylor, Ellison, Chatters, Levin, & Lincoln, 2000). For many predominately African American communities, the church has not only offered a place for spiritual healing and rejuvenation, but it has also provided mental and physical health programs to improve and maintain the wellbeing of its members (Chatters, et al., 2015). Both kinship networks and the church, broadly defined, are important sources of health-enhancing support for African Americans. Given the lack of evidence on how non-spousal familial support and the church (as a context) intersect to promote mental and emotional health among African American men, the current study examines the social and contextual experiences of older, church-going African American men and the role of their non-spousal family support in their mental health (i.e., distress). We accomplish this by using a mixed methods design that uses existing qualitative and quantitative data sources to explore issues relevant to the interpretive context within which the social and cultural experiences of distress in older African American men takes place.

METHOD

Study Design

A modified exploratory sequential design (Creswell, 2015) was used to guide the study’s framework and analysis. The study design involved two types of data collected for different primary purposes with the intent to: (a) represent different levels (and types) of analysis for the same phenomenon under study, and (b) form an overall interpretation of the phenomenon by uncovering concepts from the qualitative methods that can be tested using the quantitative methods (Creswell, 2015; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Kartalova-O’Doherty, & Doherty, 2009; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2003). We used focus group data on depression and distress from church-going African American men (n=21) 50+ years of age in southeastern Michigan and complex sample survey data from 50+ year old, church-going African American men (n=401) from the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) to build and test a conceptual model about if (and how) older African American men perceive and receive non-spousal family support and the role of this support in the psychological distress of African American men.

Qualitative Sample

The Depression Care in African American Church Elders study, or the “Churches study” is a qualitative study conducted in 2011 with African American male and female elders at predominately black churches in southeastern Michigan. The purpose of the original study was to examine the role of patient beliefs, attitudes and other factors related to adherence to depression treatments among African American men and women. The focus group participants were asked about their experiences with depression, their perceptions of depression treatments including antidepressants, reasons for not wanting formal treatment for their depression, barriers to depression treatment, and the role of personal beliefs in relation to depression care. Three focus groups (each) were conducted with African American men (n=21) and women (n=29) in predominately black Churches in southeastern Michigan. The current study only used the focus groups conducted with the men, for the purpose of addressing the unique needs of an aging and marginalized sample of African American men that has traditionally been understudied and underrepresented in studies on mental and emotional health. Characteristics of the African American men from the Churches study participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

African American Men – Churches study participants(n=21)

| Age Range | 50–87 yrs. | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Years of Education | 6–18 yrs. | |

|

| ||

| # | % | |

| Involvement in Church | ||

| Staff | 7 | 33 |

| Member | 17 | 81 |

| Chairperson/Freq Volunteer | 5 | 24 |

| Regular Attendee | 12 | 21 |

| Not Reported | 1 | 5 |

| Emotional Health | ||

| Excellent | 3 | 14 |

| Very Good | 6 | 29 |

| Good | 9 | 43 |

| Far | 2 | 10 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 3 | 15 |

| $20,001 – $30,000 | 3 | 14 |

| $30,001 – $40,000 | 6 | 29 |

| $40,001 – $50,000 | 4 | 19 |

| $50,001 – $60,000 | 3 | 14 |

| More than $60,000 | 2 | 10 |

Quantitative Sample

The National Survey of American Life (NSAL) is the most comprehensive and detailed study of mental disorders and the mental health of Americans of African descent ever completed (Jackson, et al., 2004). The NSAL is part of a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) initiative that includes three nationally representative surveys: the NSAL, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), and the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS). The NSAL is designed to explore intra-and inter-group racial and ethnic differences in mental disorders, psychological distress, and informal and formal service use, as they manifest in the context of a variety of stressors, risk and resilience factors, and coping resources among national adult and adolescent samples.

The NSAL is a household probability sample of 3570 African Americans, 1621 blacks of Caribbean descent, and 891 non-Hispanic whites, aged 18 and over. The African American sample, the core sample of the NSAL, is a nationally representative sample of households located in 48 states with at least one black adult 18 years or older who did not identify ancestral ties to the Caribbean. Most of the interviews were conducted face-to-face using a computer-assisted instrument. About 14% were conducted either entirely or partially by telephone. The final overall response rate was 72.3%. Data were collected between February 2001 and March 2003 and used a stratified and clustered sample design. Weights were created to account for unequal probabilities of selection, non-response, and post-stratification; all of which make NSAL a complex sample survey. The current study focused on the 401 African American men ages 50 and older that reported that they attended church. Table 2 presents characteristics of NSAL study participants.

Table 2.

African American Men – NSAL respondents who reported attending church (n=401)a

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | ||

| 50–59 | 186 | 48 |

| 60–69 | 119 | 29 |

| 70+ | 96 | 23 |

| Health Insurance (yes) | 340 | 88 |

| Education Level | ||

| < 11 years | 161 | 36 |

| 12 years | 110 | 28 |

| 13–15 years | 68 | 18 |

| > 15 years | 62 | 18 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Not in workforce | 197 | 47 |

| Unemployed | 13 | 4 |

| Employed | 187 | 49 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 179 | 56 |

| Partner | 11 | 3 |

| Separated | 169 | 33 |

| Never married | 39 | 8 |

| Poverty Index b | ||

| 1 | 70 | 16 |

| 2 | 96 | 21 |

| 3 | 127 | 33 |

| 4 | 108 | 30 |

Average household income was $43, 874.

Poverty status measured categorically in relation to poverty thresholds; 1 =poor, <100%; 2 = near -poor, 100 –199%;3 =non -poor with percentage of the poverty line of 200 –399%; and 4 = non -poor with percentage of the poverty line of 400% (National Center for Health Statistics, 1998)

Procedure

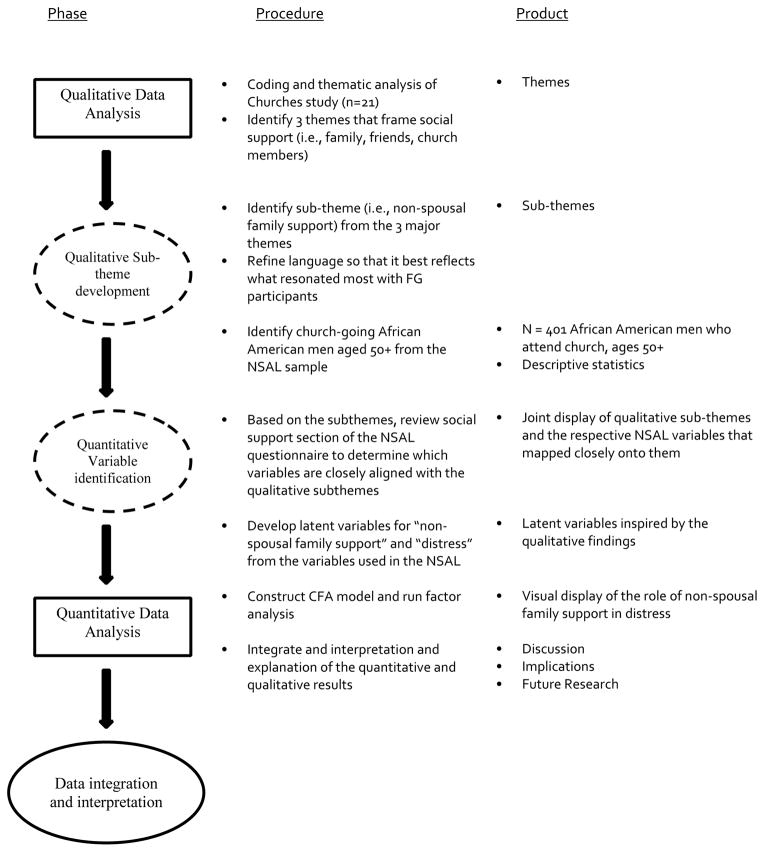

We implemented our exploratory sequential design using existing data (Figure 1), which involved analyzing the qualitative data first, followed by the quantitative data. We are coining this type of mixed methods design because our use of existing data meant that we did not need to collect any original data in order to complete the steps for our mixed methods study. First, in the qualitative phase of the study, we identified family support concepts derived from the church-going African American men ages 50 and older from the Churches study. Those data were coded and analyzed, which resulted in themes that helped to understand phenomena relevant to three types of social support (i.e., family, friends, church members) for older, church-going African American men. Our qualitative analysis included sensitivity to important cultural norms and idioms for the older, church-going African American men in our study.

Figure 1.

Procedural diagram for the mixed methods sequential exploratory design procedures

Family support, friend support, and church member support were all robust themes within themselves, each possessing multiple layers and code hierarchies. Therefore, we decided to delve deeper into each of the support themes, beginning with family support (which is the focus of this study) in order to fully-understand how each is experienced by African American men in the Churches study. Our more focused analysis of the family support theme resulted in a number of sub-themes, primarily, a differentiation between family defined as either (a) spouses/significant others, or (b) non-spouses/significant others. Especially piqued by the support offered by those who were not spouses and significant others, we decided to investigate this among the older church-going African American male sample, and to refine the language of our sub-themes so that it best reflected what resonated most with the Churches study focus group participants.

Framing our procedures in the context of the knowledge level continuum (Grinnell & Unrau, 2014) meant that we tested the conceptual model built using the qualitative Churches study data with the quantitative NSAL data. Specifically, after identifying the non-spousal family support sub-themes from the Churches study, we built a conceptual model of non-spousal family support. For the purposes of this study, and our desire to expound upon the non-spousal family support networks of older, church-going African American men, we narrowed in on the concepts that emerged from the interpersonal level and included the respondents’ family history, group identification, and social norms. Social support from non-spousal family members has been identified as vital among African American men as, oftentimes, some of them go to a friend or family member for their problems and do not seek more formal, professional help. This context was the foundation upon which we built our exploratory sequential design using existing data.

After identifying non-spousal family support concepts from the Churches study, we reviewed the social support section of the NSAL questionnaire to determine which variables are the most closely aligned with the qualitative sub-theme, non-spousal family support. Then we generated a list of social support variables from the NSAL that were aligned with non-spousal family support, and developed latent variables for both non-spousal family support and distress using measures from the NSAL. Finally, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis, integrated the qualitative and quantitative data, and then interpreted the mixed methods findings as they related to the role of non-spousal family support in distress for older, church-going African American men.

Qualitative data management and analysis

The qualitative analysis was guided by a team approach (Watkins, 2012b; Watkins & Gioia, 2015) supervised by the lead author. The study team used a spreadsheet technique to organize, manage, and analyze the data (Stockdale, 2002; Swallow, Newton, & Lottum, 2003). First, a word processing program was used to place all of the data into a table with multiple rows and columns. The development of this spreadsheet, or “all-inclusive data table,” was the first step in the analysis process. The data table included seven column headings: transcript number, questionnaire section, question asked, participant’s response, notes, code, and theme. After this data table was created, the team used a data reduction technique developed by the lead author called the “rigorous and accelerated data reduction” (RADaR) technique for qualitative data analysis (Watkins & Gioia, 2015).

The purpose of the RADaR technique is to reduce the qualitative data in a way that generates results quickly and rigorously for translation and dissemination to intended audiences. The RADaR technique is implemented using a team-based analysis approach (Fernald & Duclos, 2005; Guest & MacQueen, 2008; Watkins, 2012b; Watkins & Gioia, 2015), and was developed for the purpose of analyzing various types (e.g., focus groups, interviews, case studies, existing documents, etc.) and quantities (e.g., 5 case studies, 12 individual interviews, 8 focus groups, etc.) of qualitative data to efficiently generate results that can be incorporated into specific project deliverables. Project deliverables can range from peer-reviewed manuscripts for scientific journals to a thesis, dissertation, final report, conference presentation, book chapter, and/or health promotion materials. For the purposes of this study, the project deliverable was a manuscript that would report the findings from the guiding question: “What are the social and cultural experiences of non-spousal family support for older, church-going African American men who experience distress?”

Before beginning the RADaR technique, analysts should have already completed some of the preliminary, preparatory steps for team-based qualitative data analyses that have been described elsewhere (Fernald & Duclos, 2005; Guest & MacQueen, 2008; Padgett, 2008; Watkins, 2012b; Watkins & Gioia, 2015). The nature of the RADaR technique implies that it should be used as a tool for—and in conjunction with—completing other steps for team-based qualitative analysis. For example, the RADaR technique can occur after the team revisits the research question and becomes “one” with the data (Taylor-Powell & Renner, 2003; Watkins, 2012b) but before the team develops the data’s “open codes” (Grinnell & Unrau, 2014; Ulin et al., 2005; Watkins, 2012b). Tables and spreadsheets developed in word processing, and accompanying general-purpose computer programs (Niglas, 2007; Stockdale, 2002; Swallow et al., 2003), are the bases for the RADaR technique, as they tend to encourage the analyst to focus more on the content of the data and less on the bells and whistles that qualitative data analysis software packages have to offer.

For the purposes of this study, the data reduction tables underwent four reduction phases, and each signified a more narrow and specific presentation of the qualitative data. The RADaR technique used for the present study involved first producing an all-inclusive data table. Then, to reduce the qualitative data, the study team reviewed the all-inclusive data table and made notes about areas of commonality and overlap across groups or between participants (e.g., transcript numbers, church groups), and then generated opinions about the relevance of certain quotes and the intersection of concepts. As a part of the data reduction process, coding procedures were employed that allowed segments of raw text to be identified and compared to other segments, and analyzed for embedded meaning. A two level coding process was employed. The first level of coding (i.e., open coding) identified preliminary text segments that were used to identify categories, concepts, and themes germane to the overall project goals and objectives. During this level of coding, data were analyzed using classical content analysis, which involved identifying the frequency of codes to determine which concepts were most cited throughout the data (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2008; Watkins, 2012b).

Informal support networks, and the sub-codes therein (e.g., church, family, and friends), were identified as frequent codes that required further analysis. In other words, each of the informal support network codes were so robust, that they each required additional analyses. Thus, a more “focused” level of coding (Grinnell & Unrau, 2014; Watkins, 2012b) was used to examine each sub-code, beginning with family support networks, the focus of the current study. Once our analysis team delved deeper into family support networks, we identified both spousal and non-spousal family support constructs. Concepts and categories derived from non-spousal family support were rich in social and cultural contexts, so the team used constant comparative analysis to generate a theory, or set of concepts (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007) that further elaborated on the non-spousal family support networks of older, church-going African American men. The purpose of this level of the analysis was to acquire a deeper understanding of the non-spousal family support experiences of the Churches study participants. The analysis team worked individually, then collectively to “reduce” and code the data. These concepts were then mapped onto the NSAL questionnaire items and analyzed quantitatively, as described below.

Quantitative measures and analysis

Measures

Our mental health outcome for the quantitative phase of the study was psychological distress and was measured using the Kessler-6 (K6). This is a 6-item scale designed to assess non-specific psychological distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety in the past 30 days (Kessler, Green, Gruber, et al., 2010). The K6 is intended to identify persons with mental health problems severe enough to cause moderate to serious impairment in social and occupational functioning and to require treatment. Each item is measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). For our analysis, positive valence items were reverse coded and summed scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting higher levels of psychological distress (M = 3.37, SE = 0.18) (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81). In the psychological distress scale of the NSAL questionnaire a seventh item, adopted from the Center for Epidemiological Study - Depression (CES-D) scale (i.e., feeling “blue”) was listed, so we included this in our psychological distress measure. The results of our exploratory factor analysis (EFA) indicated that all items loaded well onto a single latent factor with all factor loadings above 0.7.

We created a latent variable, called non-spousal family support, using six factor items that described the behaviors of the Churches study respondents and their feelings toward their non-spousal members. The six items were labeled help, communication, closeness, feeling loved, listening, and expressing interests/concern. “Help” was assessed with the question “How often do people in your family-including children, grandparents, aunts, uncles, in-laws, and so on – help you out?” “Communication,” was assessed with the question “How often do you see, write, or talk on the telephone with family or relatives who do not live with you?” “Closeness” was assessed with the question “How close do you feel towards your family members?” These three questions were individual items from the NSAL questionnaire. “Feeling loved,” “listening,” and “expressing interest/concern” were measured using 3 individual items where respondents were asked “Other than your (spouse/partner) how often do your family members: 1) make you feel loved and cared for, 2) listen to you talk about your private problems and concerns, and 3) express interest and concern in your well-being?” Response categories ranged from “very often” to “never” with higher values on this index indicating higher levels of support. Cronbach’s alpha for this 6-item index was 0.77. Additionally, the results of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) supported a single latent factor solution with all factor loadings above 0.6.

Data Analysis

The NSAL includes 1,217 African American men. Of these, 401 identified as church-going, African American men ages 50 and older, and in our analyses we examined the psychological distress outcomes of these men. All analyses were weighted to be nationally representative of the populations and subgroups of interest and were conducted using STATA 13 (StataCorp, 2013). Additional analyses involved measuring the relationship between the latent, non-spousal family support variable and the pervasiveness of psychological distress for the older African American men in the sample. The means and percentages represented weighted proportions based on the sample’s race-adjusted weight measure and the standard errors reflected the recalculation of variance using the NSAL’s complex design. There were small amounts of missing data (occurring sporadically and never exceeding more than 4% of the cases for all key study variables), therefore listwise deletion was used. The data were slightly skewed but less than an absolute value of 2. The estimation method used was maximum likelihood (ML) estimation with robust errors.

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) via SVY SEM in STATA 13 to examine the factor structure and replicate previous studies that have discussed the influence of family support on mental health outcomes across church-going, African American male respondents ages 50 or older using the NSAL (Lincoln, Chatters, & Taylor, 2003). Using the conceptual model we created with the qualitative findings from the Churches study, we hypothesized that help, communication, closeness, feeling loved, listening, and expressing interests/concern will measure the latent construct “non-spousal family support,” and the seven items in our psychological distress scale will measure the latent construct “psychological distress.”

The overall fit of each construct was evaluated using multiple indicators of model fit: chi-square, the comparative fit indices (CFI), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI). The chi-square (χ2) statistic assessed the sample and implied covariance matrix and a good fitting model is indicated by a non-significant result. The comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) along with Tucker Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973) are measures for how much better the model fits the data compared to a baseline model where all variables are uncorrelated. For these indices, values above .90 indicate reasonable fit while values above .95 indicated good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Values close to 0.08 or below for the RMSEA represent acceptable model fit. In addition, we used the standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR: Joreskog & Sorborn, 1981) to determine good model fit. Ideally the SRMR should be less than .05, though values less than .08 also indicate an adequate fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Finally, we used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1974) to evaluate the alternative models, with smaller values indicating a best fitting model. Based on the models in this study, we could load items only onto a single factor, with uncorrelated measurement error terms as suggested in previous research (Boduszek et al., 2012).

RESULTS

Qualitative findings

Three overarching themes were apparent during our analysis of the family support concept, with regard to distress, in the Churches data (Table 3). In particular, focus group respondents noted that (1) they have their own processes for managing their distress, (2) their non-spousal family members were included in these processes, and (3) they depend on their non-spousal family members to support them when they experienced psychological distress. First, when participants were asked what they would do if they needed help with a mental health problem, many of them provided a sequence of steps they would follow. Specifically, many respondents noted that they would not seek professional help because they have their own processes that they undergo. These processes were oftentimes implemented when dealing with depression and/or distress, and for many participants, it began with praying and/or trying to resolve the problem on their own, prior to seeking help from a family member. Several of the focus group respondents noted that these processes were specific to (and in the context of) their families and their church. One participant noted:

“I think, the first thing I would do myself is try to find out what is the problem, why are you there, you know, why are you locked up in this? Stuck? Why are you stuck here, you know, what’s going on….”

Table 3.

Churches study qualitative themes and sub-themes

| Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| 1. African American men have a distress management “process” |

|

| 2. Family members are a part of the distress management “process” used by African American men |

|

| 3. African American men expect assistance and support from their family members |

|

When probed to talk more about the influence of their family members in their help-seeking behaviors, some of the men spoke about family more generally, while others identified specific members of their family who were particularly helpful. According to the participants, these family members were more likely to be the people they would talk to about their distress and other mental health challenges.

The second theme that emerged from the data was that non-spousal family members were intimately involved in the processes men sought for dealing with their distress. After first trying to solve the problem on their own, then seeking assistance from their spouses, the men noted that their non-spousal family members were often their third line of defense. Specifically, they discussed the importance of being able to talk to family members who knew them and who know and understand their mental health history. Beyond spouses and female partners (“I would go to my wife. She’s the one with me more than anyone else”), the participants discussed the availability of other family members, included their siblings and children. For example, one participant said “I would go to my sister who has been with me from the beginning,” while another stated:

“Well I’d go to my daughter. I have a daughter with me, my consolation. I don’t have no sister or brothers.”

During our analysis, we also noted that when the participants spoke about seeking assistance from their siblings for a mental health problem, they primarily discussed going to their sisters, but not their brothers.

The final theme that emerged from the Churches study involved how dependent the participants were on their non-spousal family members regarding their mental health and wellbeing. Participants agreed that despite stereotypes of African American men, they, themselves, depend heavily on the assistance and support of their family members, particularly, when dealing with distress. One participant noted that his son is particularly helpful.

“If my son tells me, ‘Dad, I think you ought to go to the doctor’ I go, because I can get hard-headed sometime and tough…. so yes, [he does] influence it.”

During our expansion of this theme, we noted that the men spoke freely about welcoming assistance from their non-spousal family member during difficult times, which for them occurred at various points throughout their lives. The men spoke honestly about their blemished pasts, noting that despite the ups and downs they had experienced over the course of their lives, they marked their entry (or for some, their return) to the church in their later years as a positive turning point in their mental health and overall wellbeing. The overwhelming majority of the participants in our focus groups expressed a sense of belonging and support from their church “family,” often referring to one another as “brothers,” though there were no biological relationships confirmed between them and other male church members.

Quantitative findings

After exploring the non-spousal family support experiences of the Churches study participants, the NSAL data were used to complement our qualitative findings by examine non-spousal family support and distress using a representative sample of older, church-going African American men. Our analysis of the NSAL data included a total of 401 church-going African American men ages 50 and older. We included socio-demographic measures such as household income (using the poverty index from the National Center for Health Statistics, 1998), education, employment status, and marital status. These and other characteristics of African American men from the NSAL have been reported elsewhere (Lincoln, et al., 2011; Watkins, Hudson, Caldwell, Siefert, & Jackson, 2011), so the current study focuses on using the NSAL to test the conceptual model that we built using the Churches study with the aim of illuminating the effects of non-spousal family support on psychological distress for older, church-going African American men.

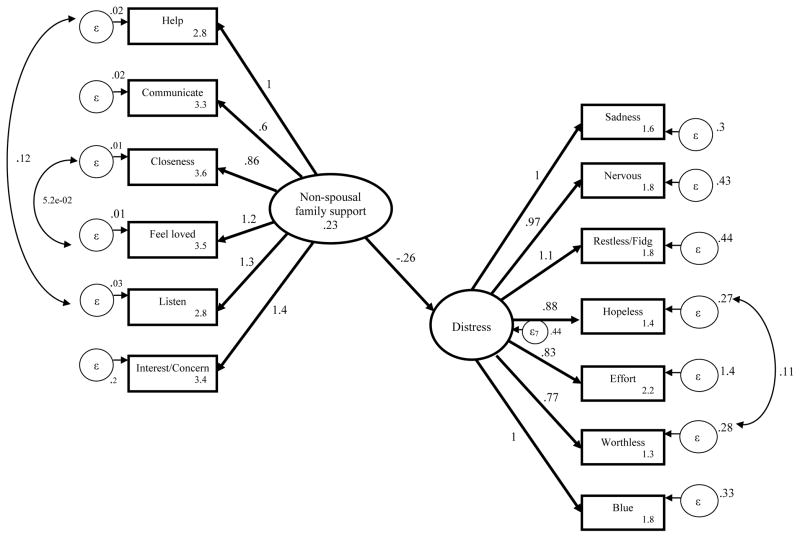

Based on our qualitative findings from the Churches data, we identified six factors (i.e., help, communication, closeness, feeling loved, listening, and expressing interests/concern) that were associated with the non-spousal family support experiences of older, church-going African American men. When we tested this conceptual model, quantitatively, we determined a good fit of the data to the hypothesized conceptual structure (Figure 2). The CFI was 0.96, the TLI was 0.96, the RMSEA is 0.05, with a 90% confidence interval of 0.04 to 0.07, and the SMR was 0.04. All four of these values indicate a good fit of our conceptual model from the Churches data onto the items selected from the NSAL (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Additionally, all items from the NSAL for both psychological distress and non-spousal family support were loaded and were found to be statistically significant (p < .05) on the theorized latent variables, and no modifications were warranted based on the values calculated (Table 4). We then tested the effect of the latent, non-spousal social support variable on psychological distress and found that non-spousal family support is associated with fewer psychological distress symptoms (β = −.26, p < .001). Further, in both our qualitative and quantitative sample results, non-spousal family support was associated with the lower scores on the psychological distress measure for older, churchgoing African American men.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model fit for non-spousal family support and psychological distress

Table 4.

Coefficients table for the structural model and measurement model

| Coefficient | Standard Error | t-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Model | ||||

|

| ||||

| Non-spousal family support | ||||

| Help | 1 | |||

| Communicate | 0.60 | 0.04 | 15.08 | < .001 |

| Closeness | 0.86 | 0.05 | 16.31 | < .001 |

| Feel loved | 1.16 | 0.06 | 19.22 | < .001 |

| Listen | 1.32 | 0.08 | 15.76 | < .001 |

| Interested/Concerned | 1.37 | 0.07 | 18.43 | < .001 |

| Psychological distress | ||||

| Depressed | 1 | |||

| Nervous | 0.97 | 0.04 | 27.36 | < .001 |

| Restless/Fidgety | 1.07 | 0.04 | 25.67 | < .001 |

| Hopeless | 0.88 | 0.04 | 24.09 | < .001 |

| Worthless | 0.83 | 0.05 | 16.96 | < .001 |

| Effort | 0.77 | 0.04 | 18.34 | < .001 |

| Blue | 1.04 | 0.05 | 22.37 | < .001 |

|

| ||||

| Structural Model | ||||

|

| ||||

| Psychological distress | − 0.26 | 0.06 | − 0.37 | < .001 |

Integration of qualitative and quantitative findings

The point of interface for this exploratory sequential design using existing data sources occurred in between the qualitative analysis phase and the quantitative item-mapping phase of the study. Table 5 is a joint data display of this interface. First, by using the Churches study to conduct an in-depth analysis of the role of non-spousal family support in the psychological distress of older, African American men, we were able to develop a conceptual model that frames the social and cultural factors that influence non-spousal family support for older, church-going African American men. Next, the themes and sub-themes derived from the Churches study were mapped onto items from the NSAL that described non-spousal family support.

Table 5.

Non-spousal family support joint data display of qualitative and quantitative findings

| Qualitative sub-themes (From Churches study) | Quantitative variables (From NSAL items) | p-value | Mixed Methods Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men reported that family members (siblings/sons/daughters) help frequently. | How often do people in your family -- including children, grandparents, aunts, uncles, in- laws and so on -- help you out? Would you say very often, fairly often, not too often, or never? | < .001 | HELP: Not only was it socially and culturally (QUAL) relevant, but it was also found to be statistically significant (QUAN) for older, Church-going African American men in the study. |

| Men reported that they communicate with family members often, and reach out to family whenever they need help. | How often do you see, write or talk on the telephone with family or relatives who do not live with you? Would you say nearly everyday, at least once a week, a few times a month, at least once a month, a few times a year, hardly ever or never? | < .001 | COMMUNICATION: Not only was it socially and culturally (QUAL) relevant, but it was also found to be statistically significant (QUAN) for older, Church-going African American men in the study. |

| Men reported that they feel close enough to family members to go to them with their mental health problems. | How close do you feel towards your family members? Would you say very close, fairly close, not too close or not close at all? | < .001 | CLOSENESS: Not only was it socially and culturally (QUAL) relevant, but it was also found to be statistically significant (QUAN) for older, Church-going African American men in the study. |

| Men reported that they feel emotionally supported by family members regarding their mental health needs. | Other than your (spouse/partner), how often do your family members make you feel loved and cared for? Would you say very often, fairly often, not too often, or never? | < .001 | FEEL LOVED: Not only was it socially and culturally (QUAL) relevant, but it was also found to be statistically significant (QUAN) for older, Church-going African American men in the study. |

| Men reported how well their family members listen to them; how they feel connected to family members. | Other than your (spouse/partner), how often do your family member listen to you talk about your private problems and concerns? Would you say very often, fairly often, not too often, or never? | < .001 | LISTEN: Not only was it socially and culturally (QUAL) relevant, but it was also found to be statistically significant (QUAN) for older, Church-going African American men in the study. |

| Men reported that their family members appear interested in their mental health needs and overall wellbeing. | Other than your (spouse/partner), how often does your family member express interest and concern in your wellbeing? Would you say very often, fairly often, not too often, or never? | < .001 | INTERESTED/CONCERNED: Not only was it socially and culturally (QUAL) relevant, but it was also found to be statistically significant (QUAN) for older, Church-going African American men in the study. |

Mapping was achieved by first creating a data mapping and triangulation table in which we listed concepts found from the Churches study data related to non-spousal family support in one column of the table. Then in the adjoining column of this data mapping and triangulation table we listed potential items (questions and response options) from the NSAL that were related to non-spousal family support. Next, a three-person team from our group held a series of meetings to rate how well the qualitative concepts (derived from the Churches study themes and sub-themes) mapped onto our proposed quantitative concepts (derived from the NSAL questionnaire). This process was performed iteratively, and involved closely examining the qualitative concepts, vetting the matching NSAL questionnaire item, then returning to the qualitative data for support and confirmation for which qualitative concepts mapped well onto the quantitative items. Disagreements among the three-person team were thoroughly discussed and resolved. The final seven factor loadings for non-spousal family support are the result of the team’s agreement about which NSAL items best represented the Churches study concepts.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to understand family support that extends beyond that of spouses and female partners (i.e., non-spousal) for churchgoing, African American men ages 50 and older. This topic is important because of the role that female partners play in the health and health behaviors of men, as well as the role of the church in helping to frame aging African American men’s ideas for how they define family and who they should seek when they experience mental health problems. Previous studies have underscored the importance of the black church in providing support for aging African Americans, but due to the way women are socialized to engage in social support, we were most interested in exploring how older, church-going men are socialized, as well as how they perceive the role of their family in offering support. We used a local qualitative study and a national quantitative study to deepen our understanding of this phenomenon. The modified exploratory sequential design employed in this mixed methods study using existing data helped to acquire depth and breadth about the non-spousal family support experiences and mental health outcomes of older, church-going African American men within their social and cultural contexts.

From our analysis of the qualitative data, we found that (beyond their spouses and female partners) older, church-going African American men most often sought support for and refuge from their distress from their siblings and children. This finding suggests that as men age, they are more likely to consult their immediate family members regarding matters involving their health. Though our primary goal for this study was to deepen our understanding of the ways in which men perceive and receive social support from their family members (outside of the support they receive from their spouses and female partners) the majority of the focus group participants discussed the important roles that their wives and female partners have in their mental health and wellbeing. With the exception of caregiving for mental illness (e.g., dementia, schizophrenia), the literature on support for more general mental health concerns (e.g., stress, distress) for men from their spouses and female partners is limited. This understudied research topic may speak to an area of study that needs further inquiry.

Our qualitative findings helped us identify a set of characteristics that older, church-going African American men found helpful from members of their non-spousal family support networks. These characteristics are consistent with previous literature framing the kind of characteristics and behaviors African American men prefer from concerned family members (Chatters, et al., 2015). Using these six characteristics to create the latent variable “non-spousal family support” was beneficial in confirming the protective factors of this type of support in reducing psychological distress for older, churchgoing African American men. Our quantitative findings suggested that the six characteristics we identified from the qualitative findings (i.e., help, communication, closeness, feeling loved, listening, and expressing interests/concern) were a good fit for our latent variable, non-spousal family support. Likewise, our quantitative analysis suggested that non-spousal family support was inversely related to distress for older, church-going African American men. This finding is aligned with those of previous studies (Chatters et al., 2015; Ward & Besson, 2012). However, previous studies often included spouses and other female partners, which is different than what we uncovered from our analysis. Specifically, we found that the role of non-spousal support networks is also important to the mental health and wellbeing for older African American men. Further, this may be especially true for men who may have outlived their spouses and partners, were never married, or live alone.

Psychological distress was selected as the outcome for this study because stress and psychological distress have been found to capture a clearer description of the mental health experiences of African American men (Watkins & Neighbors, 2007; Watkins, 2012a), oftentimes over and above the prevalence rates of clinical depression (Ward & Besson, 2012). Given the distress that African American men may experience over their lifetime, the findings from this study are helpful in expanding our current understanding about the types of family support that may be useful for older, church-going African American men. Though the church provides a welcoming and supportive setting for many African American men as they age, we found that the relationships maintained outside of the church (both spousal and non-spousal) remain strong indicators for the way African American define themselves in terms of their sense of belonging, as well as how they situate themselves within the processes used to deal with mental health challenges, should they arise.

Limitations

Despite the contributions this study makes to the influence of non-spousal family support on the psychological distress of older, church-going African American men, it is not without its limitations. For example, although there are strengths in the design of this study, weaknesses exist that the reader should note while interpreting the findings. First, our analysis of the qualitative data from the Churches study is likely a reflection of our study team’s reflexive approaches to the family support characteristics that are germane to our personal and professional lives. The study team consisted of five women from different racial, ethnic, and religious backgrounds, with no members of the team holding a membership in any of the churches from this study. Therein, we acknowledge that the qualitative phase of our mixed methods study may look very different had another team of researchers conducted the analysis.

Second, though we were successful in implementing an exploratory sequential design using mixed methods in this study, the mapping of existing qualitative concepts onto existing quantitative variables is still evolving and not without its limitations. Our review of previous studies suggests that existing data sources are usually used at the beginning (or for the first single-method phase) of a mixed methods study. However, as qualitative and quantitative data sources become more robust and sophisticated, the potential for implementing entire mixed methods studies using data that were previously collected for different purposes is promising. Our use of an existing qualitative data source (the Churches study) to build a conceptual model and then using the NSAL (an existing quantitative data source) was a unique opportunity to capitalize on comprehensive and expansive measures of non-spousal family support for older, church-going African American men. Our integration of the qualitative and quantitative data was an attempt to make connects between two data sources with different original purposes. Though this was an innovative use of existing data, there are still limitations associated with using existing data sources for purposes beyond that of the original studies.

Finally, we acknowledge that our study was focused on the non-spousal family support experiences of church-going African American men, thus, not speaking to the experiences of non-churchgoing African American men. The implications for this exclusion are important to note, as older men, in general, tend to require more support for their health and daily living (Watkins, 2012a). So not being connected to a church or other social network as they age may exacerbate poor mental health for African American men. Despite this, and the other aforementioned limitations, the findings from this mixed methods study offers an innovative model for how two different data sources with two paradigm foci, can be integrated to expand on the current depth and breadth of the current discourse around the role of non-spousal family support in the mental health of older, church-going African American men.

Implications

The findings from this study have implications for future research topics, methods, and interventions. It is noteworthy to underscore that despite our goal to uncover characteristics of non-spousal family support, the majority of the men identified spouses and female partners as their primary support persons for when they are dealing with distress. This finding has implications for the role of women in the mental health decisions of men, which is a limited topic that has been addressed sparsely in previous research (Exception: Watkins, Abelson, & Jefferson, 2013). Future studies should expound on the role of women in men’s mental health, beyond the role often acquired by women as the caregiver of men with chronic disease and severe mental illness. Future studies should also expand on the current scholarship in this understudied area by cross-referencing data from men and female partners about the mental health and wellbeing of the men. Furthermore, this topic would also benefit from deeper inquiry into the similarities and differences among the various types of support African American men receive from their family, church, community networks, and their healthcare providers.

As for this study’s implications for future interventions, programs that target African American men need a culturally sensitive, gender-specific approach that specifically addresses the unique characteristics of this population (Aronson, Whitehead, & Baber, 2003; Watkins, Green, Goodson, Guidry, & Stanley, 2007). Due to the risks associated with poor health and wellbeing, multidisciplinary interventions designed to address the intersection of these various health determinants are especially needed (Courtenay, 2000; Watkins, 2012a). Courtenay (2003) noted that the development of multidisciplinary methods to study men’s health will require addressing the various health determinants involved and the disciplinary differences in outcome measures, population studies, methodologies applied, and rigor of program evaluations. These requirements will be especially relevant for work with older African American men.

With regard to the implications of this study for expanding research methods, use of qualitative and quantitative approaches promise to bridge the explanatory gap that exists between aggregated outcomes and experiences regarding the phenomenon of interest. Accordingly, the current mixed methods study explores issues relevant to the interpretive context within which the social and cultural context of psychological distress among older African American men takes place. In addition, mixed methods research will contribute to the development and integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches that provide the best models for how to comprehensively represent qualitative data involving inductive exploration alongside deductive examinations of the hypothesis-testing relationships found in quantitative approaches.

Using mixed methods to study the non-spousal family support of older, church-going African American men lends itself to truly capitalizing on the what each of the single-methods (qualitative and quantitative) can offer for the purposes of exploration and discovery in this understudied area. For instance, the lack of research on the social support networks of older African American men who experience psychological distress means that this area is in need of further inquiry into the social and cultural experiences of this unique sub-group of African American men. Qualitative methods offer opportunities to dig deeper into not just what older church-going African American men experience, but also how they experience it, described in their own words. On the contrary, quantitative methods offer a chance to ascertain prevalence rates and the scope of the outcomes at the national level. Nationally representative data on the mental health and wellbeing of older African American men are limited, particularly when compared to existing national data on white men. However, the NSAL is one of the largest mental health surveys to sample African Americans; thus, offering our team a chance to not only examine the breadth of psychological distress and non-spousal family support among older, churchgoing African American men, but also to use qualitative data to build a conceptual model that we could test using a representative sample of older, church-going African American men from the NSAL. This innovative use of mixed methods with existing qualitative and quantitative data expands our topic area, as well as the possibilities for more creative ways of analyzing and integrating other existing qualitative and quantitative data sources and building on the work of our mixed methods predecessors by taking our definition of mixed methods to the next level.

Conclusion

It is often assumed that, by virtue of their church affiliation, older African American men experience more resilience to their life stressors and emerge with better mental health outcomes compared to their younger counterparts. However, under certain circumstances the church, alone, may not provide the type of protection needed to improve and maintain positive mental health outcomes for older African American men. Though some studies support this (Chatters, et al., 2015; Dessio, et al., 2004; Ward & Besson, 2012; Watkins, 2012a), others assert that in the absence of family, the church can provide a familial grounding for African Americans that results in positive health and well-being overall. To further examine this assertion, this study used existing data sources to examine how non-spousal family support influences psychological distress among older, church-going African American men.

Contributor Information

Daphne C. Watkins, University of Michigan

Tracy Wharton, University of Central Florida.

Jamie A. Mitchell, University of Michigan

Niki Matusko, University of Michigan.

Helen Kales, University of Michigan.

References

- Anderson EA, Kohler JK, Letiecq BL. Predictors of depression among low-income, nonresidential fathers. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:547–567. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson RE, Whitehead TL, Baber WL. Challenges to masculine transformation among low-income African American males. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):732–741. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazeley P. Integrating data analyses in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2009;3(3):203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Boduszek D, Shevlin M, Mallett J, Hyland P, O’Kane D. Dimensionality and construct validity of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale within a sample of recidivistic prisoners. Journal of Criminal Psychology. 2012;2(1):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Buttram ME, Kurtz SP. A mixed methods study of health and social disparities among substance-using African American/Black men who have sex with men. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2015;2(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0042-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Antonakos C, Tsuchiya K, Assari S, De Loney EH. Masculinity as a moderator of discrimination and parenting on depressive symptoms and drinking among nonresident African American fathers. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2013;14:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Nicklett EJ. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23(6):559–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton MT, Thompson NJ, Kaslow NJ. Social environment factors associated with suicide attempt among low-income African Americans: the protective role of family relationships and social support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2005;40(3):175–185. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner KO, Copeland VC, Grote NK, Rosen D, Albert S, McMurray ML, … Koeske G. Barriers to treatment and culturally endorsed coping strategies among depressed African-American older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2010;14(8):971–983. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.501061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JN, Hall J. Understanding black male student athletes’ experiences at a historically black college/university: A mixed methods approach. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. in press. Published online before print. November 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;50(10):1385–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00390-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH. Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2003;2(1):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Curry L, Nunez-Smith M. Mixed methods in health sciences research: A practical primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dessio W, Wade C, Chao M, Kronenberg F, Cushman LE, Kalmuss D. Religion, spirituality, and healthcare choices of African-American women: Results of a national survey. Ethnicity and Disease. 2004;14:189–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis K, Caldwell CH, Assari S, De Loney EH. Nonresident African American fathers’ influence on sons’ exercise intentions in the Fathers & Sons Program. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2014;29(2):89–98. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130417-QUAN-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald DH, Duclos CW. Enhance your team-based qualitative research. Annals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(4):360–364. doi: 10.1370/afm.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines JS. Social correlates of psychological distress among adult African American males. Journal of Black Studies. 2007;37:827–858. [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell RM Jr, Unrau YA, editors. Social work research and evaluation. 10. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen K. Reevaluating guidelines for qualitative research. In: Guest G, MacQueen K, editors. Handbook for team-based qualitative research. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press; 2008. pp. 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Haight W, Bidwell LN. Mixed methods research for social work. Chicago, IL: Lyceum Books; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JB, Moore CE, Powe BD, Agarwal M, Martin P. Perceptions of support among older African American cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2010;37(4):484–493. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.484-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L. Feel the heat!: The unrelenting challenge of young black male unemployment: policies and practices that could make a difference. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.clasp.org/resources-and-publications/files/Feel-the-Heat_Web.pdf.

- Hesse-Biber SN. Mixed methods research: Merging theory with practice. New York, NY: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Report. 2012;61(6):1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt TR. Toward a deeper understanding of the meaning of marriage among Black men. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;34(7):859–884. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):112–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kartalova-O’Doherty Y, Doherty DT. Satisfied careers of persons with enduring mental illness: Who and why? International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2009;55(3):257–271. doi: 10.1177/0020764008093687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Bromet E, Cuitan M, Furukawa TA, Gureje O, Hinkov H, Hu CY, Lara C, Lee S, Mneimneh Z, Myer L, Oakley-Browne M, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Viana MC, Zaslavsky AM. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19(S1):4–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular social support on self-rated health in late life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61(1):S35–S43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly. 2007;22(4):557–584. [Google Scholar]

- Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Qualitative data analysis: A compendium of techniques and a framework for selection for school psychology research and beyond. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23(4):587–604. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Watkins DC, Chatters LM. Correlates of psychological distress and major depressive disorder among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21(3):278–288. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littrell J, Beck E. Predictors of depression in a sample of African-American homeless men: Identifying effective coping strategies given varying levels of daily stressors. Community Mental Health Journal. 2001;37:15–29. doi: 10.1023/a:1026588204527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac an Ghaill M. The Making of Men: Schooling, Masculinities and Sexualities. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Marti TS, Mertens D. Editorial. Mixed methods research with groups at risk: New developments and key debates. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2014;8(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 1998 with socioeconomic and health chart book. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Musick MA, Williams DR. The African American minister as a source of help for serious personal crises: bridge or barrier to mental health care? Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25(6):759–777. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW, Woodward AT, Bullard KM, Ford BC, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS. Mental health service use among older African Americans: the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16(12):948–956. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318187ddd3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niglas K. Media review: Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet software. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1:297–299. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research. Vol. 36. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI. The stress process revisited: Reflections on concepts and their interrelationships. In: Aneshensel C, Phelan J, editors. Handbook of sociology of mental health. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 1999. pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Rich JA. The health of African American men. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2000;569:149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Roy KM, Dyson O. Making daddies into fathers: Community-based fatherhood programs and the construction of masculinities for low-income African American men. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;45(1–2):139–154. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellman J, Granara C, Rosengarten G. Barriers to depression care for black older adults. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2011;37(6):13–17. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20110503-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitgraves C. The benefits of marriage for African-American men. New York: Institute for American Values; 2008. Report no. 10. Retrieved from http://center.americanvalues.org. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdale MS. Analyzing focus group data with spreadsheets. American Journal of Health Studies. 2002;18:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Swallow V, Newton J, Lottum CV. How to manage and display qualitative data using “Framework” and Microsoft® Excel. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003;12:610–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang TS, Brown MB, Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Social support, quality of life, and self-care behaviors among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2008;34(2):266–276. doi: 10.1177/0145721708315680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Powell E, Renner M University of Wisconsin - Extension, Program Development and Evaluation. Analyzing qualitative data. 2003 Retrieved from website: http://learningstore.uwex.edu/assets/pdfs/g3658-12.pdf.

- Taylor RJ, Ellison CG, Chatters LM, Levin JS, Lincoln KD. Mental health services in faith communities: The role of clergy in black churches. Social Work. 2000;45(1):73–87. doi: 10.1093/sw/45.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Religious media use among African Americans, Black Caribbeans and Non-Hispanic Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Journal of African American Studies. 2011;15:433–454. doi: 10.1007/s12111-010-9144-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Findings from the national survey of American life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62(4):S238–S250. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.s238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Forsythe-Brown I, Taylor HO, Chatters LM. Patterns of emotional social support and negative interactions among African American and Black Caribbean extended families. Journal of African American Studies. 2014;18(2):147–163. doi: 10.1007/s12111-013-9258-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative methods in public health: A field guide for applied research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ward EC, Besson DD. African American men’s beliefs about mental illness, perceptions of stigma, and help-seeking barriers. The Counseling Psychologist. 2012;41(3):359–391. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC. Depression over the adult life course for African American men: Toward a framework for research and practice. American Journal of Men's Health. 2012a;6(3):194–210. doi: 10.1177/1557988311424072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC. Qualitative research: The importance of conducting research that doesn’t ‘count’. Health Promotion Practice. 2012b;13(2):153–158. doi: 10.1177/1524839912437370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Hudson DL, Caldwell CH, Siefert K, Jackson JS. Discrimination, mastery, and depressive symptoms among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21:269–277. doi: 10.1177/1049731510385470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Neighbors HW. Social determinants of depression and the black male experience. In: Treadwell HM, Xanthos C, Holden KB, editors. Social determinants of health among African-American men. 2012. pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Gioia D. Mixed methods research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. Pocket guides to social work research series. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Green BL, Goodson P, Guidry J, Stanley CA. Using focus groups to explore the stressful life events of black college men. Journal of College Student Development. 2007;48(1):105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DC, Abelson JM, Jefferson SO. ‘Their depression is something different… it would have to be:’ Findings from a qualitative study of black women’s perceptions of black men’s depression. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2013;7(4Suppl):42–54. doi: 10.1177/1557988313493697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]