Abstract

Parental rejection is linked to deep and enduring adjustment problems during adolescence. This study aims to further clarify this relation by demonstrating what has long been posited by parental acceptance/rejection theory but never validated empirically – namely that adolescents’ unique or subjective experience of parental rejection independently informs their future adjustment. Among a longitudinal, multi-informant sample of 161 families (early adolescents were 47% female and 40% European American) this study utilized a multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis to isolate for each early adolescent-parent dyad, the adolescent’s distinct view of parental rejection (i.e., the adolescent unique perspective) from the portion of his or her view that overlaps with his or her parent’s view. The findings indicated that adolescents’ unique perspectives of maternal rejection were not differentiated from their unique perspectives of paternal rejection. Also, consistent with parental acceptance-rejection theory, early adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection were associated with worse adjustment (internalizing and externalizing) one year later. This study further demonstrates the utility and validity of the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach for identifying and examining adolescent unique perspectives. Both conceptually and analytically, this study also integrates research focused on unique perspectives with a distinct but related line of research focused on discrepancies in perspectives.

Keywords: Unique perspectives, Parental rejection, Internalizing, Externalizing, Early adolescence

Introduction

Whether retrospective or prospective, national or multi-national, or focused on an adolescent’s relationship with mothers, fathers, or both, over a half-century’s worth of research converges to indicate that parental rejection is linked to deep and enduring adjustment problems, including both concurrent and future internalizing and externalizing problems (Khaleque & Rohner, 2002; Putnick et al., 2015; Rohner, Khaleque, & Cournoyer, 2012). A large portion of the research focused on parental rejection is grounded in Rohner’s parental acceptance-rejection theory (Rohner et al., 2012). Regarding the effects of parental rejection on adolescent adjustment, Rohner and colleagues (Rohner, 2004, Rohner et al., 2012) consistently posit that (a) it is the experience of rejection on the part of the adolescent that informs adjustment, and (b) the experience of rejection is, at least to a certain extent, subjective. Rohner typically grounds this position within symbolic interaction theory (Stryker, 1972), which posits that family roles (e.g., adolescent, mother, and father) help mold and structure expectations and agendas surrounding family interactions, and, to the extent that these expectations and agendas differ across family roles, family members will evaluate and interpret the same interactions differently from one another.

Although Rohner has long postulated the existence of the adolescent’s subjective or unique perspective of parental rejection as well as its importance to the adolescent’s current and future adjustment, whether or not these postulates are valid has not been directly examined empirically. The lack of empirical work on unique perspectives is, in good part, attributable to the fact that unique perspectives have generally proven difficult to capture empirically (Dyer, Day, & Harper, 2014; Jager, Bornstein, Putnick, & Hendricks, 2012; Jager, Yuen, Bornstein, Putnick & Hendricks, 2014). Additionally, while the sizable body of research on discrepancies between adolescent and parent perspectives has yielded valuable insights regarding dyad disagreement and its consequences (De Los Reyes, 2011), this area of work is not equipped to capture and analyze family members’ unique perspectives because dyad disagreement effectively conflates or combines the adolescent and parent unique perspectives with one another. However, an approach developed by Jager et al. (2012, 2014) provides researchers with a method for quantifying family members’ unique perspectives. Although to date their method has been applied to family triads, here we extend the approach of Jager et al. (2012, 2014) by applying it to the shared and unique perspectives of family subsystems (or dyads) as opposed to the family system.

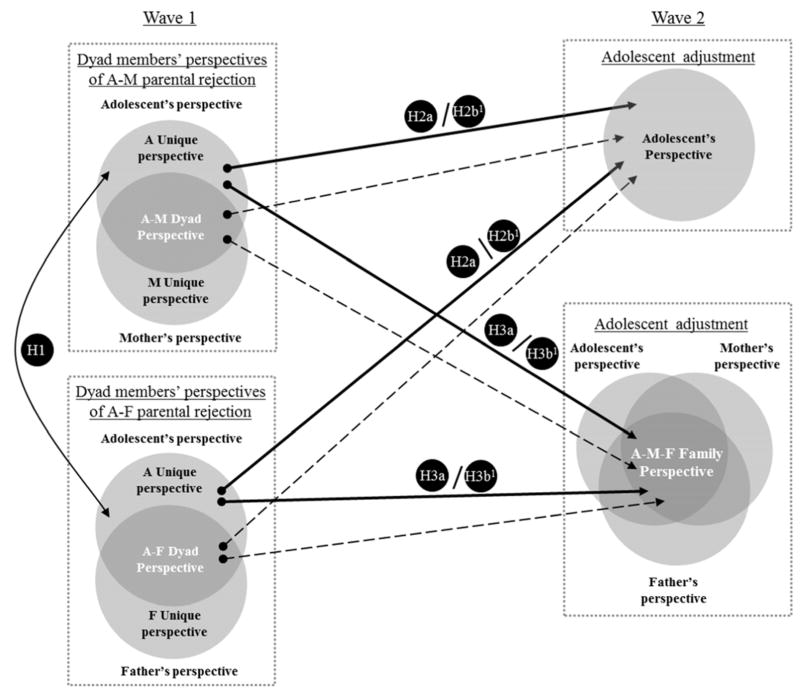

Specifically, we focus on early adolescents’ unique perspectives as well as adolescent-parent shared perspectives of parental rejection within both adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyads. Dyad members’ shared and unique perspectives of adolescent-mother and adolescent-father parental rejection are illustrated graphically in Figure 1, which is conceptual in nature and assumes perfect measurement. Where the adolescent and mother perspectives and adolescent and father perspectives overlap and are similar to one another are the adolescent-mother and adolescent-father shared or “dyad” perspectives, respectively. Conceptually, a dyad perspective is the view of parental rejection that is shared by both dyad members and thus captures similarity in both dyad members’ perspectives of parental rejection. Unique perspectives are the portion of each dyad member’s perspective of parental rejection that does not overlap with the other dyad member’s perspective. Conceptually, a unique perspective is the view of parental rejection that is idiosyncratic to each member of the dyad and thus captures each dyad member’s distinct view of parental rejection. Although both dyad members have a unique perspective of the dyad, given the aims of this study, we only focus on the adolescent’s unique perspectives of mother and father rejection. Using longitudinal data spanning one year, for our first aim we examine the extent to which adolescents’ unique perspective of parental rejection generalizes across both adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyads. For our second aim, we examine whether adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection predict future internalizing and externalizing, even after controlling for adolescent-parent dyad perspectives.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for adolescent’s unique and shared perspectives of parental rejection and their relations to Wave 2 adolescent perspectives of internalizing and externalizing as well as family perspectives of internalizing and externalizing. A = adolescent; M = mother; F = father. H = hypothesis (e.g., H1 = hypothesis 1). 1Controls for Wave 1 measure of Wave 2 outcome.

Parental Rejection

As measured via the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (Rohner et al., 2012), parental acceptance-rejection theory conceptualizes parental acceptance-rejection as ranging across a single continuum and consisting of four distinct, but interrelated facets: a warmth/affection facet situated at the acceptance side of the continuum and three other facets – hostility/aggression, undifferentiated rejection, and indifference/neglect - all situated at the rejection side of the continuum. However, as Rohner acknowledged (Rohner, 2004), most adolescent-parent dyads are characterized by aspects of both acceptance and rejection (i.e., even adolescents who feel supported and loved by their parents occasionally experience hurtful emotions and behaviors), suggesting that acceptance and rejection are not merely opposite ends of the same continuum. Moreover, whether based on adolescent reports (Rohner & Cournoyer, 1994) or parent reports (Abramson, Mankuta, Yagel, Gagne, & Knafo-Noam, 2014; Comunian & Gielen, 2001) of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire, mounting psychometric evidence indicates that these four facets comprise two distinct factors, with the warmth facet comprising an “acceptance” or warmth factor and the three other facets (hostility/aggression, undifferentiated rejection, and indifference/neglect) comprising a distinct “rejection” factor. These “acceptance” and “rejection” factors are only modestly correlated (across studies, correlations ranged from .29 to .55). Additionally, whether using the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire or other measures of parental rejection that have distinct subscales for acceptance and rejection, numerous studies indicate that, even when ignoring the direction of effects and focusing on just the magnitude of effects, acceptance and rejection are differentially predictive of a range of outcomes cross-sectionally (Muris, Meesters, & van den Berg, 2003) and longitudinally (Lieb et al., 2000). Given the mounting psychometric evidence along with research indicating that acceptance and rejection are differentially predictive of both current and future outcomes, for the purposes of this study we focus on the three facets (hostility/aggression, undifferentiated rejection, and indifference/neglect) that have repeatedly been found to form the “rejection” factor when examining adolescent unique perspectives and adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyad perspectives of parental rejection.

Across-dyad generalizability of adolescents’ unique perspectives

According to Symbolic Interaction Theory (Stryker, 1972), roles and positions shape one’s perceptions of social interactions. Because the adolescent has similar, if not equivalent, roles and positions within both the adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyads, there is reason to expect commonality between the adolescent’s unique reality of the adolescent-mother dyad and the adolescent’s unique reality of the adolescent-father dyad. Determining whether adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection are distinct from one another or dyad specific or are generalizable across dyads has implications for future research as well as therapeutic interventions focused on rejected children and adolescents. If adolescents’ unique perspectives of rejection are dyad-specific, then they would need to be addressed individually in future research and in therapeutic interventions. However, the greater their generalizability (i.e., the more they are equivalent to one another), the more research and interventions can address both of the adolescent’s unique perspectives jointly.

Are adolescents’ unique perspectives predictive of future adolescent adjustment?

Parental acceptance-rejection theory (Rohner et al., 2012) posits that the adolescent’s perception or experience of parental rejection is partially subjective and it is this subjective experience that, to an extent, underlies the effects of rejection on adjustment. However, whether this is the case is unclear from available research because, by focusing on adolescent self-reports of parental rejection, available research (Lieb et al., 2000; Rohner et al., 2012) has effectively pooled the adolescent’s unique perspective with the portion of his or her perspective that is also shared with mother (for adolescent-mother rejection) or father (for adolescent-father rejection). Thus, for both the adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyads it is not clear whether any found effects from existing research are a function of the adolescents’ unique perspectives, the adolescent-parent dyad perspectives, or both.

Available research that regresses adolescent adjustment on both adolescent and parent reports of adolescent-parent relationship quality may potentially provide insight regarding the relationship between adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection and adolescent adjustment. This approach, which amounts to a main effects multiple regression model, identifies the effect of adolescent reports on adjustment independent of parent reports (and vice-versa). Although use of this approach is not very common, generally research utilizing it (De Los Reyes, Goodman, Kliewer, & Reid-Quinones, 2010, Laird & Weems, 2011; Pelton & Forehand, 2001) has found that one’s own report of relationship quality predicts one’s own report of adolescent adjustment over and above the other dyad member’s report of relationship quality (e.g., controlling for parental reports of relationship quality, adolescent reports of relationship quality predict adolescent reports of their own adjustment and vice-versa). However, for two reasons these findings provide limited insight regarding the relation between adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection and adolescent adjustment. First, to date no work utilizing this approach has specifically focused on parental rejection. Second, and perhaps more importantly, because this multiple regression approach (a) does not account for measurement error, and (b) to date has only demonstrated that one’s own reports (whether it be adolescent or parent) of family functioning are independently predictive of one’s own reports of adolescent adjustment, it unclear if the effects found are valid or simply an artifact of common reporter variance due to measurement error.

Although not focused on reporters’ unique perspectives, there is a considerable body of research focused on adolescent-parent discrepancies, as measured through difference scores, indicating that adolescent-parent discrepancies in dyad relationship quality are related to adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems (De Los Reyes, 2011; De Los Reyes et al., 2010; Pelton & Forehand, 2001). However, for three reasons this line of research provides limited insight regarding the relationship between adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection and adolescent adjustment. First, while research linking adolescent-parent discrepancies to adolescent outcomes has focused on discrepancies in adolescent-parent relationship quality (e.g., conflict, monitoring), to date, no work has focused specifically on discrepancies in parental rejection. Second, as described earlier, while arguably related to one another, adolescent-parent discrepancies, which in effect confound the adolescent and parent unique perspectives with one another, are not equivalent to adolescent unique perspectives. Thus, research utilizing discrepancy scores effectively addresses a different research question (i.e., how does the entire discrepancy between adolescent and parent perspectives relate to adolescent adjustment) than the more precise question we hope to address here (i.e., how does the adolescent unique perspective – or the portion of dyad disagreement attributable to the adolescent - relate to adolescent adjustment). Third, and perhaps most importantly, recent work strongly questions the construct validity of discrepancy scores as measures of differences in perspective (De Los Reyes, Salas, Menzer, & Daruwala, 2013; Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013; Laird & Weems, 2011). Thus, not only is research utilizing discrepancy scores addressing a different research question than we hope to address here, there also is strong reason to doubt whether the answers it provides are valid.

More recent work has examined the effect of adolescent-parent discrepancies on adolescent adjustment using an interactive multiple regression approach, which focuses on the predictive effects of the interaction between parent and adolescent reports (Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013; Ohannessian & De Los Reyes, 2014). While the validity of the interactive multiple regression approach is promising (De Los Reyes et al., 2013; Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013), as was the case with difference scores, no work utilizing the interactive multiple regression approach has focused specifically on discrepancies in reports of parental rejection. Moreover, like difference scores, the interactive multiple regression approach confounds the effect of the adolescent unique perspective with the effect of the parent unique perspective and, thereby, is not equipped to identify the specific effect of adolescent unique perspectives.

Empirically capturing adolescent unique perspectives

The aim of a multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis is to isolate trait variance from method variance because method variance is typically sizable but of little theoretical or substantive interest. By reinterpreting “trait” variance as shared variance across different family members and “method” variance as variance specific to each family member, Jager et al. (2012, 2014) were able to identify and examine family members’ shared and unique perspectives of the family system.

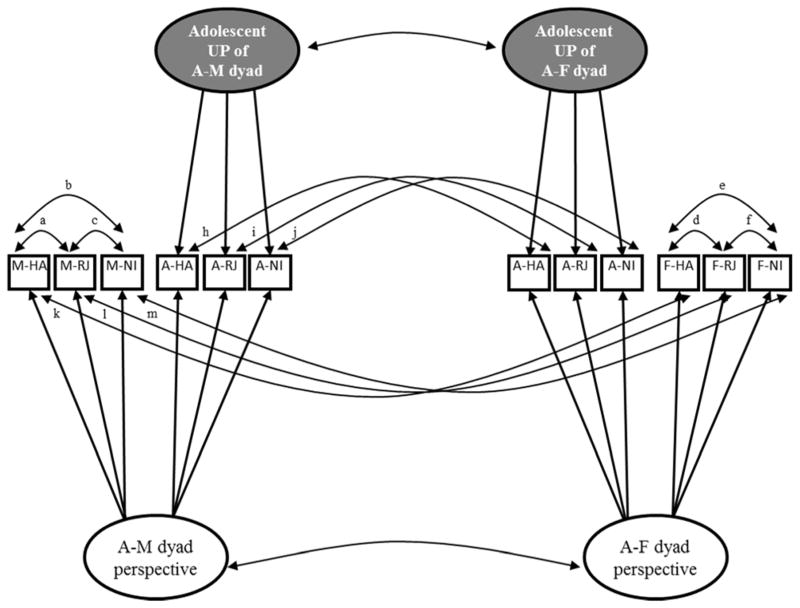

Adapting this approach to examine shared and unique perspectives of family subsystems or dyads, here we utilized a multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis to separate for each adolescent-parent dyad the adolescent unique perspective of parental rejection from the shared perspective (i.e., dyad perspective) of parental rejection (see Figure 2). Specifically, we extracted dyad perspectives for each of the adolescent-mother (i.e., A-M dyad factor) and adolescent-father (i.e., A-F dyad factor) dyads by loading both dyad members’ reports on a single factor (i.e., dyad perspective factors).

Figure 2. Multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis model extracting dyad and adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection.

White ovals are shared dyad perspectives; gray ovals are adolescent unique perspectives. A = adolescent; M = mother; F = father. UP = unique perspective. HA = hostility/aggression; RJ = undifferentiated rejection; NI = neglect/indifference.

After extracting variance common to both dyad members, the “non-shared” variance remaining for each observed variable is a combination of variance idiosyncratic to the individual (i.e., their unique perspective) plus measurement error. For each dyad we isolated variance idiosyncratic to the adolescent from measurement error by loading the adolescent’s reports for that specific dyad on a single factor (i.e., Adolescent unique perspective of adolescent-mother dyad, Adolescent unique perspective of adolescent-father dyad). The two adolescent unique perspective factors were allowed to covary. Because dyad members’ unique perspectives are independent of dyad perspectives, we fixed the covariance among the adolescent unique perspective factors and the adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyad perspective factors to zero. To account for the variance idiosyncratic to each parent (i.e., shared variance across a parent’s set of reports after extracting variance common to both dyad members), we utilized a “correlated uniqueness” approach (Kenny & Kashy, 1992), which entails allowing the residual variances of the mother’s reports to covary (covariances a, b, and c in Figure 2) and then likewise for the father’s reports (covariances d, e, and f). Unlike a conventional multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis model, we also covaried across-dyad adolescent reports1 (covariances g, h, and i) and across-dyad parent reports2 (covariances j, k, and l).

The Current Study

For our first aim, we examined whether adolescent unique perspectives of adolescent-mother and adolescent-father rejection were correlated with one another. Specifically, consistent with Symbolic Interaction Theory, we expected that adolescents’ unique perspectives of maternal and paternal rejection would be positively correlated with one another (Hypothesis 1, Figure 1). For our second aim we examined whether adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection predicted future internalizing and externalizing. Consistent with parental acceptance-rejection theory, we expected that, after accounting for the effects of both dyad perspectives, adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection would be positively associated with the adolescents’ perceptions of future internalizing and externalizing problems, both without (Hypothesis 2a; Figure 1) and with (Hypothesis 2b) controls for initial internalizing and externalizing problems.

As part of our second aim we also focused on family perspectives of adolescent internalizing and externalizing (i.e., variance in reports of adolescent internalizing and externalizing that is common across adolescent, mother, and father reports) in order to remove reporter-specific measurement error as a potential confound. That is, a potential explanation for any association found between adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection and adolescents’ perceptions of their own adjustment (as posited by hypotheses 2a and 2b) is that adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection merely captured their tendency to self-report information in an erroneous way (i.e., reporter-specific measurement error), and, because this reporting bias extended to all of their self-reports (including their self-reported adjustment), adolescents’ unique perspectives were associated with adolescents’ own self-reported adjustment. Unlike self-reports, family perspectives of adolescent adjustment fully removed reporter-specific measurement error as a potential confound because adolescents’ reporter-specific measurement error would not be absorbed into the family perspective of adolescent adjustment, which necessarily is limited only to the variance that is common across all family members’ reports of adolescent adjustment. Because we believed that adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection capture more than just reporter-specific measurement error, we expected that after accounting for the effects of both dyad perspectives, adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection would be positively associated with family perspectives of future internalizing and externalizing problems, both without (Hypothesis 3a; Figure 1) and with (Hypothesis 3b) controls for initial internalizing and externalizing problems.

Methods

Participants

Families were originally recruited through letters sent home from schools serving a socioeconomically diverse population within the metropolitan area of a U.S. Mid-Atlantic state. To insure economic diversity, adolescents were sampled from private and public schools, and from high- to low-income families in proportions representative of the community from which adolescents were sampled. If parents had more than one adolescent eligible for participation, only the first adolescent for whom consent forms were received was enrolled. Of the 274 families providing data at Wave 1, analyses were limited to the 161 families that had Wave 1 data from adolescent, mother, and father (i.e., all three family members provided self-report data). Not surprisingly, compared to those families excluded from the analyses (n = 113) because they lacked self-report data from one or more family members, the families included in the analyses (n = 161) were more likely to be intact. After controlling for whether or not families were intact, those excluded from the analyses did not differ from those included in the analyses in terms of ethnicity, family income, parental education, or adolescent gender or age.

Among the analytic sample (n = 161), youth were, on average, early adolescents at around 10 years of age (M = 9.61, SD = .62) at Wave 1 and around 11 years of age (M = 10.64, SD = .62) at Wave 2, diverse in ethnicity (European American = 65 (40%), African American= 41 (25%), and Latin American = 55 (35%)), and 75 (47%) were female). The analytic sample consisted of families that were mostly intact (75%), middle-class (on a 10-point scale M = 6.82, which corresponds to an annual income ranging from $41,000 to $50,000, SD = 2.85), and had mothers (M years of education = 14.06, SD = 4.67) and fathers (M years of education = 14.07, SD = 4.44) who, on average, completed some college. Attrition was minimal across Wave 1 and Wave 2; of the 161 families from Wave 1, 154 (95.6%) were retained approximately one year later at Wave 2. Moreover, with respect to adolescent and family demographics, those retained did not differ from those lost to attrition.

Procedure

Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, schools, or at another location chosen by the participants. All parents signed statements of informed consent, and all adolescents signed statements of assent. Family members completed questionnaires independently. Parents were given modest compensation for their participation, and adolescents were given small gifts.

Measures

Reliabilities for all of the (sub)scales used here are listed in Table 1. Control variables included adolescent age, gender, and ethnicity as well as family structure (intact versus not intact) and family SES (based on maternal and paternal education and annual family income).

Table 1.

Intercorrelations and descriptive statistics for Wave 1 parental rejection subscales and Wave 2 adolescent adjustment

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | M | SD | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 Dyad hostility, reject, neglect | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Adolescent→Mother | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Hostility | -- | 1.15 | .30 | .69 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Reject | .50 | -- | 1.13 | .29 | .56 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Neglect | .58 | .61 | -- | 1.35 | .42 | .61 | |||||||||||||||

| Mother→Adolescent | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Hostility | .03 | −.04 | .00 | -- | 1.16 | .23 | .71 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Reject | .15 | .02 | .10 | .31 | -- | 1.09 | .22 | .55 | |||||||||||||

| 6. Neglect | .17 | .19 | .25 | .21 | .15 | -- | 1.31 | .35 | .60 | ||||||||||||

| Adolescent→Father | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Hostility | .80 | .50 | .59 | .01 | .18 | .20 | -- | 1.14 | .23 | .70 | |||||||||||

| 8. Reject | .47 | .50 | .47 | .07 | .13 | .19 | .58 | -- | 1.13 | .36 | .65 | ||||||||||

| 9. Neglect | .39 | .54 | .64 | .12 | .08 | .16 | .43 | .45 | -- | 1.35 | .43 | .66 | |||||||||

| Father→Adolescent | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Hostility | .16 | −.02 | −.05 | .27 | .12 | .09 | .15 | .25 | −.01 | -- | 1.14 | .23 | .71 | ||||||||

| 11. Reject | .11 | .11 | .01 | .02 | .09 | .16 | .05 | .14 | .01 | .26 | -- | 1.09 | .25 | .61 | |||||||

| 12. Neglect | .13 | −.04 | .04 | .20 | .20 | .40 | .13 | .16 | .08 | .35 | .27 | -- | 1.39 | .44 | .63 | ||||||

| Wave 2 Adolescent Adjustment | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Adolescent→Adolescent | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. Internalizing | .50 | .40 | .50 | .03 | .16 | .21 | .47 | .25 | .33 | −.13 | .08 | −.09 | .641 | .39 | .27 | .89 | |||||

| 14. Externalizing | .39 | .33 | .46 | .08 | .27 | .18 | .49 | .33 | .29 | −.07 | −.02 | −.08 | .70 | .631 | .22 | .18 | .87 | ||||

| Mother→Adolescent | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Internalizing | .15 | .04 | .11 | .24 | .21 | .19 | .19 | .15 | .11 | .19 | .11 | .23 | .21 | .17 | .751 | .22 | .19 | .87 | |||

| 16. Externalizing | .13 | .06 | .08 | .26 | .25 | .18 | .24 | .27 | .07 | .28 | .17 | .20 | .10 | .27 | .69 | .781 | .21 | .18 | .91 | ||

| Father→Adolescent | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Internalizing | .28 | .17 | .24 | −.01 | .05 | .12 | .37 | .18 | .13 | .17 | .06 | .22 | .24 | .15 | .38 | .32 | 621 | .22 | .19 | .87 | |

| 18. Externalizing | .15 | .14 | .14 | .05 | .25 | .11 | .34 | .24 | .06 | .19 | .11 | .11 | .15 | .35 | .27 | .59 | .59 | .591 | .21 | .16 | .85 |

Note. For Wave 1 hostility, reject, and neglect subscales, within-reporter, across-subscale correlations are in bold and across-reporter, within-subscale correlations are underlined.

Denotes a correlation between a scale’s Wave 2 and Wave 1 measure. Adolescent→Mother = adolescent report of adolescent-mother dyad; Mother→Adolescent = mother report of adolescent-mother dyad; Adolescent→Father = adolescent report of adolescent-father dyad; Father→Adolescent = father report of adolescent-father dyad. All correlations greater or equal to .15 are significant at the .05 level.

Parental rejection

At Wave 1 the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form (PARQ/Control-SF; Rohner et al., 2012) was used to assess adolescent and parent reports of rejection within the adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyads. Each adolescent completed the PARQ/Control-SF twice, once each for mother and father. Aside from interchanging “mother” with “father”, the wording of the items did not vary. Each mother and father completed the PARQ/Control-SF once, and the wording of the items was the same for mother and father. The PARQ/Control-SF consists of 29 items, each having a possible range of 1 (almost never) to 4 (every day). The 29 items form 5 sub-scales. As identified by previous psychometric work (Abramson et al. 2014; Comunian & Gielen, 2001; Rohner & Cournoyer, 1994), three of the subscales form the rejection dimension - hostility-aggression (six items; e.g., “My mother hits me, even when I do not deserve it”; hereafter referred to as hostility), undifferentiated rejection (four items; e.g., “My mother lets me know I am not wanted”; hereafter referred to as rejection), and neglect-indifference (six items; e.g., “My mother pays no attention to me”; hereafter referred to as neglect). The fourth and fifth subscales (warmth-affection and parental control, respectively) consist of the final eleven items and were not used for this study. For each reporter, the mean scores of subscales were used, with higher scores reflecting higher dysfunction.

Adolescent adjustment

At Waves 1 and 2, adolescent internalizing and externalizing were assessed by adolescent report (via the Youth Self Report; YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), mother report (via the Child Behavior Checklist; CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), and father report (via the CBCL). Externalizing behaviors were assessed using the combined Aggressive Behavior (20 items; e.g., YSR: “I get in many fights,” CBCL: “Gets in many fights”) and Delinquent (13 items; e.g., YSR: “I lie or cheat,” CBCL: “Lies or cheats”) YSR and CBCL subscales. Internalizing behaviors were assessed using the combined Withdrawal (nine items; e.g., YSR: “I keep from getting involved with others,” CBCL: “Keeps from getting involved with others), Somatic Complaints (nine items; e.g., YSR: “I feel overtired,” CBCL: “Feels overtired”), and Depression-Anxiety (14 items; e.g., YSR: “I feel unhappy, sad, or depressed,” CBCL: “Feels unhappy, sad, or depressed) YSR and CBCL subscales.

Results

All analyses were conducted with Mplus Version 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) and used a maximum likelihood estimator that is robust to nonnormality. We used Kline’s (2015) guidelines to assess model fit, which specify that comparative fit index (CFI) values > .95 and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values < .05 constitute a good fit. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Identification of optimal multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis

With confirmatory factor analyses in general, and multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analyses (MTMM-CFAs) in particular, mis-identified solutions are common and important to avoid because, even when providing an excellent fit, misidentified solutions can still yield biased or incorrect parameter estimates (Kenny & Kashy, 1992; Marsh, 1989). Common forms of misidentification include out-of-range estimates, Heywood cases (negative error variances), and nonconvergence (Kenny & Kashy, 1992; March, 1989). Regarding MTMM-CFAs, the most common cause of misidentification is model misspecification due to extracting more factors than the data support (Rindskopf, 1984). Aside from indications of misidentification, other indicators of overfactoring are (a) poor discriminant validity (i.e., correlations among latent factors approaching 1.0), and (b) poor convergent validity (i.e., a sizable proportion of the loadings for a particular factor are small and nonsignificant).

Given these susceptibilities of MTMM-CFAs, we began by identifying the superior MTMM-CFA model. We used the following criteria to determine the superior MTMM-CFA: (a) fit indices and change of model fit (e.g., χ2, CFI, RMSEA) from nested models, (b) indications of model misidentification, and (c) the degree of convergent and discriminant validity. We began with the a priori model presented in Figure 2. This model provided an acceptable fit, χ2(46) = 53.308, p = .21, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .03, but it suffered from poor convergent and discriminant validity as well as model misidentification. Specifically, as an indication of poor convergent validity, the factor loadings for the A-M Dyad Factor were all non-significant. As an indication of model misidentification, the residual variances for two indicators were negative. Finally, as an indication of both model misidentification and poor discriminant validity, the correlation between the Adolescent Unique factor for the adolescent-mother dyad and the Adolescent Unique factor for the adolescent-father dyad was greater than 1.0 (r = 1.07, p < .001), indicating that these two factors are empirically redundant and should be combined into a single factor.

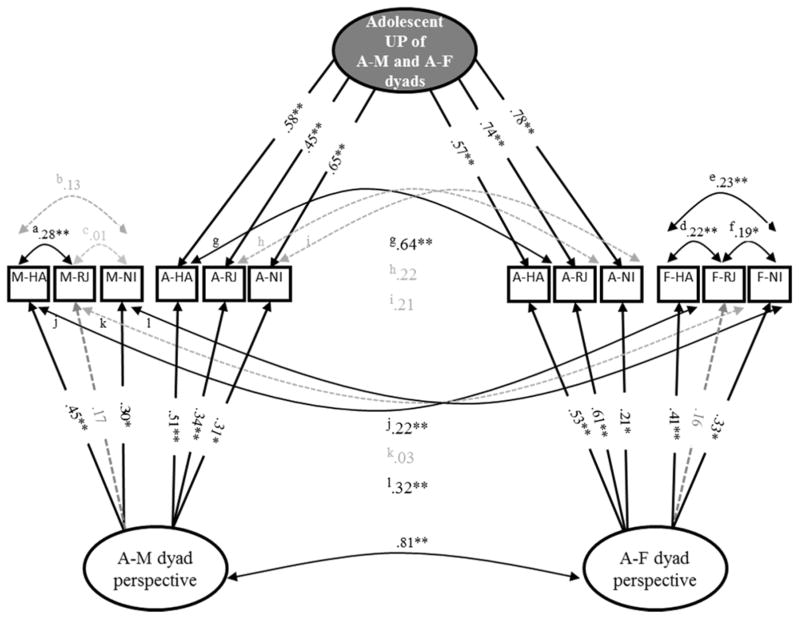

Consequently, we revised the model in Figure 2 by specifying a single Adolescent Unique factor (i.e., six adolescent indicators of parental rejection all loading onto a single factor). This revised model (Figure 3) provided an excellent fit, χ2(47) = 51.680, p = .30, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .02, showed no indications of misidentification, and displayed good convergent and discriminant validity. Regarding convergent validity, for both the A-M and A-F dyad factors, five of the six factor loadings were statistically significant. Additionally, for the Adolescent Unique factor every factor loading was statistically significant, indicating that, after the shared variance across dyad members’ reports was accounted for via the dyad factors, common variance remained across the adolescents’ reports of parental rejection. Regarding discriminant validity, although the A-M dyad factor and the A-F dyad factor strongly covaried with one another (r = .81, p < .001), they were empirically distinct, Δχ2(1) = 3.86, p < .05 (i.e., a two-factor solution fit better than a single-factor solution).

Figure 3. Optimal multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis extracting dyad and adolescent unique perspectives of parent-child rejection.

White ovals are shared dyad perspectives; gray ovals are adolescent unique perspectives. A = adolescent; M = mother; F = father. UP = unique perspective. HA = hostility/aggression; NI = neglect/indifference; RJ = undifferentiated rejection. Gray-dashed paths are non-significant at .05 level. Model fit: χ2(47) = 51.680, p = .30, CFI = .992, RMSEA = .025.

a,b,c,d,e,fWhen significant, these residual covariances indicate that common variance remained across a given parent’s own reports of parental rejection after shared variance across dyad members’ reports was accounted for via the Dyad Factor.

g,h,iWhen significant, these residual covariances indicate that common variance remained across an adolescent’s two reports of a given facet of rejection after accounting for common variance already captured via the correlation between Dyad Factors and their dual loadings on the adolescent Unique Factor.

j,k,lWhen significant, these residual covariances indicate that common variance remained between parents’ reports of the same facet of rejection after accounting for shared variance across parents’ reports of the same facet via the correlation between Dyad Factors.

**p < .01; *p < .05.

Across-dyad generalizability of adolescents’ unique perspectives

Because the two Adolescent Unique factors (i.e., Unique factor for adolescent-mother dyad and Unique factor for adolescent-father dyad) could be collapsed into a single Unique factor, our expectation that the adolescent unique perspective of adolescent-mother rejection would be positively correlated with the adolescent unique perspective of the adolescent-father rejection (Hypothesis 1) was supported. Indeed, having all six adolescent reports (i.e., the three reports of adolescent-mother rejection and the three reports of adolescent-father rejection) load onto a single factor is equivalent to the following model: the adolescent’s three reports of adolescent-mother rejection load on one unique factor, the adolescent’s three reports of adolescent-father rejection load on a second unique factor, and the correlation between the two unique factors is set to 1.0. Thus, because the optimal model entailed collapsing the two Adolescent Unique factors into a single Unique factor, we found that the two Unique Factors correlated and more specifically that they were empirically indistinguishable from one another.

Adolescent unique perspectives and adolescent perspectives of adolescent adjustment

For adolescent-reported internalizing and externalizing at Wave 2, we built on the model in Figure 3 by including each as an observed variable and regressing it on the following Wave 1 factors: Adolescent Unique factor, A-M Dyad factor, and A-F Dyad factor (Model 1, Table 2). Next, building on this first set of models, for each model we auto-regressed a given Wave 2 indicator of adjustment on itself at Wave 1 (Model 2, Table 2). All analyses used residual measures of Wave 2 adolescent internalizing and externalizing that adjusted for adolescent age, gender, and ethnicity, and family structure and SES. Because of the high correlation between the two dyad factors, we constrained the regression coefficients of the two dyad factors to be equal (e.g., for self-reported internalizing the regression coefficients for the two dyad factors are equal to one another in Table 2). Doing so yielded more reliable estimates for the dyad factors and did not impact model fit. Although not a focus of this study, in only one instance were the dyad factors associated with a Wave 2 outcome: when not controlling for Wave 1 externalizing, the Dyad Factors were positively associated with Time 2 Externalizing (.172; Model 1, Table 2).

Table 2.

Wave 1 dyad and adolescent Unique perspectives of parental rejection predicting Wave 2 adolescent internalizing and externalizing

| Adolescent self-report | A-M-F Family Factor | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| W2 Internalizing

|

W2 Externalizing

|

W2 Internalizing

|

W2 Externalizing

|

|||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| W1 A-M Dyad Perspective | .07 | −.04 | .17** | .04 | .31**(.24)** | −.03(−.03) | .35**(.32)** | −.02(−.01) |

| W1 A-F Dyad Perspective | .07 | −.04 | .17** | .04 | .31**(.24)** | −.03(−.03) | .35**(.32)** | −.02(−.01) |

| W1 Adolescent Unique Perspective | .53** | .25** | .42** | .20* | .20*(.37)* | −.02(.10) | .21*(.19)* | −.01(.00) |

| W1 Stability | -- | .53** | -- | .51** | -- | .89**(.73)** | -- | .93**(.77)** |

Note. All estimates are standardized. All estimates control for adolescent age, gender, and race/ethnicity, as well as family structure and family SES. A = adolescent; M = mother; F = father. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2. The estimates in parentheses are based on analyses using family mean scores (i.e., the mean of adolescent, mother, and father reports) of adolescent adjustment.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Consistent with hypothesis 2a, we found that the Adolescent Unique Perspective of parental rejection at Wave 1 was positively associated with adolescent self-reported internalizing (.53; Model 1, Table 2) and externalizing (.42; Model 1, Table 2) at Wave 2. Thus, adolescents with higher unique perspective factor scores (their unique perspective is characterized by higher rejection relative to other adolescents) were also higher on self-reported internalizing and externalizing at Wave 2. Consistent with hypothesis 2b, we also found that the Adolescent Unique Perspective of parental rejection at Wave 1 remained positively associated with Wave 2 internalizing (.25) after controlling for Wave 1 internalizing and with Wave 2 externalizing (.20) after controlling for Wave 1 externalizing (Model 2, Table 2). Thus, for internalizing and externalizing, the higher an adolescent’s unique factor score of parental rejection at Wave 1, the more his or her position (relative to other adolescents) worsened across Time 1 and Time 2. Put another way, the higher an adolescent’s unique factor score (relative to other adolescents) of parental rejection at Wave 1, the more his or her rank (relative to other adolescents) in both internalizing and externalizing at Wave 2 was higher than his or her rank at Wave 1.

Adolescent unique perspectives and family-perspectives of adolescent adjustment

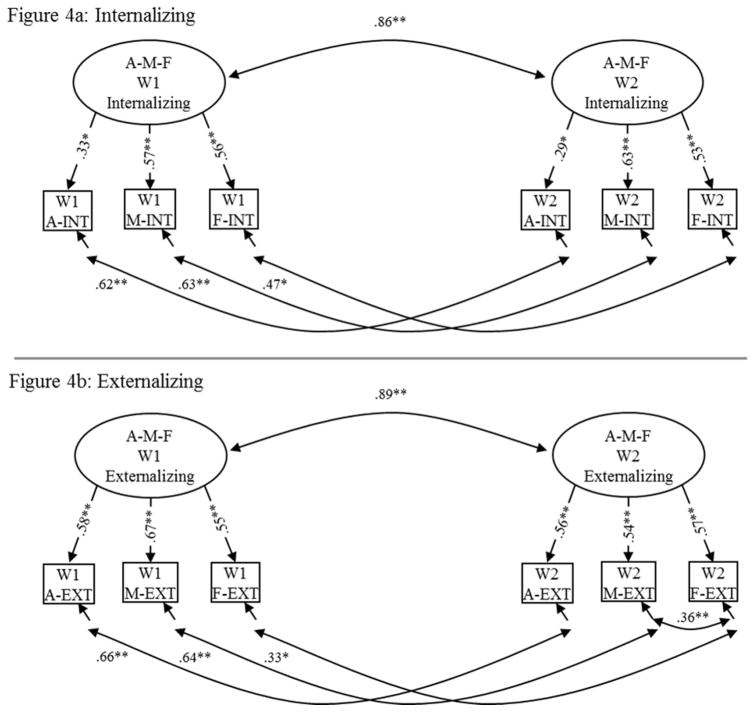

To identify family perspectives of adolescent internalizing we loaded separately for each wave all three family members’ reports of adolescent internalizing onto a single factor (see Figure 4a). In doing so, we isolated for each wave the common variance across all three family members’ reports. We specified a similar model for adolescent externalizing (see Figure 4b). In both models we allowed the family perspectives of adolescent adjustment to covary across wave. Additionally, when significant, we allowed (a) within-reporter residual covariances to covary in order to account for any reporter-specific variance and (b) within-wave, across-parent residual covariances to covary in order to account for any parent-specific agreement in adolescent adjustment. Both models provided an excellent fit (See Figure 4). We used the FSCORE command (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012) to output factor scores for the family factors. All analyses used residual indicators of internalizing and externalizing that adjusted for adolescent age, gender, and ethnicity, and family structure and SES.

Figure 4. Confirmatory factor analyses used to identify family perspectives of adolescent internalizing and externalizing.

All estimates listed are standardized. A = Adolescent; M = Mother; F = Father. INT = internalizing; EXT = externalizing. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2. Figure 4a model fit: χ2(5) = 2.24, p = .81, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00. Figure 4b model fit: χ2(4) = 6.32, p = .72, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .020. All indicators of internalizing and externalizing are adjusted for adolescent age, gender, and ethnicity, and family structure and SES.

**p < .01; *p < .05.

Mirroring the analytical approach we utilized for adolescent-reported adjustment, we built on the model in Figure 3 by including each Wave 2 Family Factor as an observed variable and regressing it on the following Wave 1 factors: Adolescent Unique factor, A-M Dyad factor, and A-F Dyad factor (Model 1, Table 2). Next, building on this first set of models, for each model we auto-regressed a given Wave 2 family factor on itself at Wave 1 (Model 2, Table 2). Once again, due to the high correlation between the two parental rejection dyad factors, we constrained the regression coefficients of the two dyad factors to be equal. Although not a focus of this study, when not controlling for Wave 1 adjustment, the Wave 1 Dyad Factors of parental rejection were associated with the Wave 2 Family Factors of internalizing (.31; Model 1, Table 2) and externalizing (.35; Model 1, Table 2). Both effects however were reduced to non-significance after controlling for Wave 1 adjustment.

Consistent with hypothesis 3a, we found that the Adolescent Unique Perspective of parental rejection at Wave 1 was positively associated with the internalizing (.20; Model 1, Table 2) and externalizing (.21; Model 1, Table 2) Family Factors at Wave 2. Thus, adolescents with higher unique perspective factor scores (relative to other adolescents, their unique perspective of Wave 1 rejection is characterized by higher dysfunction) were members of families that had higher family perspective factor scores of adolescent adjustment (relative to other families, their family factor scores for adolescent internalizing and externalizing were characterized by higher dysfunction) at Wave 2. Inconsistent with hypothesis 3b, for each Wave 2 Family Factor, we found that its relation with the Wave 1 Adolescent Unique perspective of parental rejection was no longer significant after controlling for their Wave 1 family factor (Internalizing: −.02; Model 2, Table 2; and Externalizing: −.01; Model 2, Table 2).

Finally, as a robustness check (Duncan, Engel, Claessens, & Dowsett, 2014), we used an alternative operationalization of family perspectives of adolescent adjustment and sought to replicate our findings regarding the relations between the adolescent’s Wave 1 unique perspective of parental rejection and the family’s Wave 2 family perspectives of adolescent adjustment. Specifically, as opposed to family factor scores (as identified in Figure 4) we calculated “family mean scores”, which are the average of the three family members’ reports for each domain of adjustment (internalizing and externalizing) at each wave. Unlike the family factor scores, the family mean scores assume that (a) each family member’s report contributes equally to the family’s perspective, and (b) that 100% of the variance from each family member’s report is absorbed into the family’s perspective. As we did for analyses involving family factor scores, for these analyses we used residual family mean scores that adjusted for adolescent age, gender, ethnicity, and family structure and SES. In terms of overall pattern as well as instances of statistical significance, the findings based on family mean scores, which are listed in parentheses within Table 2, matched the findings based on family factor scores.

Discussion

Although relationships with parents undergo profound transformation during adolescence, parents remain critically important sources of guidance and emotional support (Jager, 2011; Laursen & Collins, 2009). Indeed, when these sources of guidance and emotional support are not available, as is the case with parental rejection, available research indicates that adolescents are far more likely to exhibit deep and enduring adjustment problems (Jager, Yuen, Putnick, Hendricks, & Bornstein, 2015; Khaleque & Rohner, 2002; Rohner, et al., 2012). Our study extends and clarifies this line of research by demonstrating what has long been posited by parental acceptance-rejection theory (Rohner et al., 2012) but never validated empirically – namely, that adolescents’ unique or subjective experience of parental rejection independently informs their future adjustment. Importantly, these findings both empirically validate existing theory and provide greater specificity regarding the linkage between parental rejection and adolescent adjustment. We also found, as expected, across-dyad generalizability in adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection. More specifically we found complete across-dyad generalizability such that adolescent unique perspectives of maternal rejection were not differentiated or distinct in any way from adolescent unique perspectives of paternal rejection. Given that adolescent thinking becomes increasingly sophisticated, abstract, and multidimensional as adolescents age (Kuhn, 2009), a potential explanation for our finding of complete across-dyad generalizability in early adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection is that early adolescents may not yet be equipped cognitively to comprehend and recognize finer distinctions between their views of maternal and paternal rejection. Thus, although a topic for future research, it may be that across-dyad generalizability in adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection is age-graded, such that the unique perspectives of maternal and paternal rejection differentiate as adolescents age.

Adolescent Unique Perspectives of Parental Rejection and Adolescent Adjustment

For both adolescent-perspectives and family perspectives (whether measured via family factor scores or family mean scores) of adolescent adjustment, adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection predicted higher internalizing and externalizing behaviors one year later. These findings are consistent with parental acceptance-rejection theory and suggest that adolescents’ unique experience of parental rejection independently informs future adjustment. These findings also have implications for therapeutic interventions. Because the effects of parental rejection on future adjustment appear to at least partly flow from early adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection, therapeutic interventions aimed at curbing the effects of parental rejection should focus attention on adolescents’ unique perspectives of rejection. Additionally, given that we found complete across-dyad generalizability in adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection, it does not appear that interventions need to address adolescents’ unique perspectives of maternal and paternal rejection individually to be effective. However, to the extent that adolescents’ unique perspectives of maternal and paternal rejection become more differentiated as adolescents age, a possibility noted above, therapeutic interventions involving older adolescents would need to address adolescent unique perspectives of maternal and paternal rejection separately.

For adolescent perspectives of adolescent adjustment, after controlling for initial levels the effects of adolescent unique perspectives on future adolescent adjustment remained significant, indicating that adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection were associated with adolescent perspectives of worsening internalizing and externalizing one year later. However, the same was not true of family perspectives (whether through family factor scores or family means scores) of adolescent adjustment, the effects of which were reduced to non-significance after controlling for initial levels. One potential reason for this contrast in findings is that because stability across Waves 1 and 2 was considerably higher for family perspectives than it was for adolescent perspectives of adolescent adjustment, there was, after controlling for Wave 1 levels, simply less unexplained variance in family perspectives of adolescent adjustment for the unique perspectives to predict. Another potential explanation for this contrast in findings is that what adolescent perspectives of adjustment capture is qualitatively distinct from what family perspectives of adolescent adjustment capture. That is, in terms of both quantity and quality, internalizing and externalizing often vary across the home and school contexts (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987; De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Whereas adolescents may be more likely to take into account their behavior at both home and school when self-reporting their adjustment, parents more likely focus primarily on the adolescent’s behavior they witness in the home when reporting on their adolescent’s adjustment (De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Consequently, whereas family perspectives may primarily capture the adolescent’s adjustment within the home context, adolescent perspectives likely capture the adolescent’s adjustment across both the home and school contexts. Thus, it may be that adolescent unique perspectives predict instability in adolescent adjustment when broadly construed (i.e., across home and school context) but not when narrowly construed (i.e., more limited to the home context). The notion that adolescent and family perspectives of adolescent adjustment are qualitatively distinct measures may also help explain why dyad perspectives of parental rejection were more consistently predictive of family perspectives of adolescent adjustment.

Unique Perspectives capture something “real” about the adolescent’s experience

Because we found that the adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection are associated with both adolescent perspectives and family perspectives (or the family’s “shared reality”) of adolescent adjustment, our findings indicate that adolescent unique perspectives capture more than just reporter-specific measurement error. That is, because (a) family perspectives of adolescent adjustment contain only variance common across reporters and therefore contain no reporter-specific measurement error and (b) we found that family perspectives of adolescent adjustment were significantly associated with adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection, it necessarily follows that adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection are comprised of more than just reporter-specific measurement error.

Demonstrating that adolescent unique perspectives of parental rejection are more than just reporter-specific measurement error is important. If variance captured by adolescent unique perspectives does not actually capture how adolescents uniquely feel or think about parental rejection, but instead captures their systematic tendency to self-report information in an erroneous way (i.e., reporter-specific measurement error), then the association between adolescent unique perspectives and their own self-reported adjustment would be specious and its implications for researchers and practitioners would be severely compromised. Given that Jager et al. (2014) found that adolescent and father unique perspectives of family functioning each predicted the adolescent-father dyad perspective or “shared reality” of dyad functioning, there is mounting evidence indicating that adolescents’ (as well as other family members’) unique perspectives capture important information about the family and its subsystems, as opposed to just reporter-specific measurement error.

Although unique perspectives are more than just reporter-specific measurement error, it does not necessarily follow that unique perspectives reflect objective reality or are bias free. Indeed, unique perspectives may reflect bias – albeit experiential bias as opposed to reporter bias. That is, to the extent that an adolescent’s perspective is less objectively valid than his or her parents’, the portion of the adolescent’s perspective that is distinct from his or her parents’ perspectives (i.e., his or her unique perspective) would not capture objective reality but, instead, the adolescent’s experiential bias. Of course, the reverse would be true when the adolescent’s perspective is more objectively valid than his or her parents’ perspectives, which some research indicates is the case when it comes to family members’ perceptions of family functioning (Hawley & Weisz, 2003). Nonetheless, whether objectively true or not, unique perspectives appear to capture something “real” about the adolescent’s experience of parental rejection (as demonstrated here) and family functioning (as demonstrated by Jager et al., 2014).

Unique perspectives versus discrepancies in perspectives: comparing and contrasting

As described earlier, adolescent-parent discrepancies – provided that they are examined via interactive multiple regression as opposed to the discrepancy score approach3 -effectively represent the combination of multiple unique perspectives and thereby confound reporters’ unique perspectives with one another. Consequently, what the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach used here intends to capture (i.e., reporters’ unique perspectives) is qualitatively different from what the interactive multiple regression approach intends to capture (discrepancies between different reporters). Arguably then, the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach is more precise because, unlike the interactive multiple regression approach, the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach identifies a given reporter’s specific contribution to across-reporter disagreement, and thereby clears up any ambiguity surrounding to what extent (or even if) each reporter contributes to a dyad (or triad) discrepancy.

Putting this distinction aside, it is the case that both the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach and the interactive multiple regression approach do address what could more broadly be termed “diverging perspectives”. As such, we view the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach and the interactive multiple regression approach as complementary approaches (as opposed to competing or redundant approaches) that together provide adolescent researchers with an expansive methodological toolkit for examining “diverging perspectives” between adolescents and their family members. However, when it comes to addressing diverging perspectives, the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach and the interactive multiple regression approach each have advantages and disadvantages. In terms of measurement, the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach is more advantaged because, unlike interactive multiple regression (Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013), the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach removes random measurement error when examining diverging perspectives. Consequently, the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis should yield more precise and reliable measures of both diverging perspectives and their effects. Additionally, in terms of application, the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach is more flexible than the interactive multiple regression approach in two ways. First, although both the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach and the interactive multiple regression approach can be used to examine the predictive effects of diverging perspectives (i.e., diverging perspectives can be specified as independent variables), only the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach can be used to examine the size of diverging perspectives (Jager et al., 2012) as well as the predictors and covariates of diverging perspectives (i.e., diverging perspectives can be specified as dependent variables). This is because, unlike the interactive multiple regression approach, the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach (via the unique factor) produces a tangible measure of a diverging perspective that can, in turn, be assessed and/or included as an outcome or a covariate. Second, between the interactive multiple regression and multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approaches, only the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach is capable of simultaneously examining the effects of diverging (i.e., unique) and converging (i.e., shared) perspectives and, thereby, illuminating the effects of diverging perspectives relative to converging perspectives. Finally, whereas the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach is more advantaged in terms of measurement and more flexible in terms of application, the interactive multiple regression approach is far less complex analytically. Consequently, relative to the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach, the interactive multiple regression approach is more straightforward to execute and has more modest sample size requirements.

Finally, we caution researchers against using the main effects multiple regression approach (i.e., regressing adolescent adjustment on adolescent and parent reports of relationship quality). We do so because in terms of measurement and application, the main effects multiple regression approach has the same limitations as the interactive multiple regression approach (i.e., the main effects multiple regression approach does not account for measurement error, it does not allow for specifying diverging perspectives as dependent variables, and it is not capable of simultaneously examining the effects of diverging and converging perspectives). However, whereas there is compelling evidence to suggest that both the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach and the interactive multiple regression approach are reliable and valid approaches for testing the effects of diverging perspectives, there is no such evidence for the main effects multiple regression approach.

Limitations

This study has three limitations. First, although the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire and its variants, such as the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form, are widely used, validated measures with demonstrated reliability (Rohner et al., 2012), for both adolescent and mother reports, the reliability of the undifferentiated rejection subscale was low (e.g., slightly below .60). Nonetheless, for both adolescent and mother, this subscale correlated highly with each reporter’s other Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form subscales, as indicated in Table 1, suggesting that, despite its low reliability, the subscale captured sizable and meaningful variance that overlapped with the other Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form subscales. Second, because the model that specified a separate adolescent unique perspective for maternal and paternal rejection did not properly converge, we could not formally compare its fit to our final, well-fitting model that specified a single adolescent unique perspective. Third, given the complexity of multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analyses, the study’s sample size, although certainly large for a longitudinal, multi-informant family data set, was not large enough to allow for multiple group analyses. Consequently, we could not explore the effects of potential moderators, such as children’s gender and ethnicity.

Conclusions

This study adds to the body of research examining adolescent-parent differences in perspectives both substantively and methodologically. Substantively speaking, although long posited by parental acceptance-rejection theory (Rohner et al., 2012), this study is the first to empirically demonstrate that adolescents’ unique perspectives of parental rejection independently inform adolescent adjustment. In doing so, these findings provide greater specificity regarding the linkage between parental rejection and adolescent adjustment. Moreover, given that we found that adolescents’ unique perspectives of maternal rejection were not differentiated from adolescents’ perspectives of paternal rejection, collectively our findings suggest that when therapeutic interventions involving rejected adolescents focus on adolescents’ unique perspectives, they can address unique perspectives of maternal and paternal rejection jointly (as opposed to individually). Methodologically speaking, this study further demonstrates the utility and validity of the multitrait-multimethod confirmatory factor analysis approach for identifying and examining adolescent unique perspectives and integrates, both conceptually and analytically, unique perspectives with existing research focused on discrepancies in perspectives. In doing so, this study highlights how these two distinct areas of research complement one another and together can help illuminate the predictors and consequences of adolescent-parent differences in perspectives.

Footnotes

These covariances account for variance unique to the adolescent that is not dyad-specific but is specific to a given facet of rejection.

These covariances capture any shared variance across mother and father reports that is independent of shared variance across mother and father reports already accounted for via the covariance between adolescent-mother and adolescent-father dyad perspectives.

Although there is evidence to support the validity of the interactive multiple regression approach (Laird & De Los Reyes, 2011), recent work (Laird & Des Los Reyes, 2013; De Los Reyes et al., 2013) strongly questions the validity of the discrepancy score approach. Consequently, we caution researchers against using the discrepancy score approach to examine adolescent-parent discrepancies.

References

- Abramson L, Mankuta D, Yagel S, Gagne JR, Knafo-Noam A. Mothers’ and Fathers’ prenatal agreement regarding postnatal parenting. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2014;14:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101(2):213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comunian AL, Gielen UP. An Italian study of parental-acceptance-rejection. In: Roth R, Neil S, editors. A matter of life: Psychological theory, research, and practice. Lengerich, Germany: Pabst Science Publishers; 2001. pp. 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A. Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of adolescents and children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40(1):1–9. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DAG, Burgers DE, Rabinowitz J. The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin. 2015;141(4):858–900. doi: 10.1037/a0038498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Goodman KL, Kliewer W, Reid-Quinones K. The longitudinal consistency of mother-child reporting discrepancies of parental monitoring and their ability to predict child delinquent behaviors two years later. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(12):1417–30. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9496-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Salas S, Menzer MM, Daruwala SE. Criterion validity interpreting scores from multi-informant statistical interactions as measures of informant discrepancies in psychological assessments of children and adolescents. Psychological Assessment. 2013;25(2):509–519. doi: 10.1037/a0032081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Engel M, Claessens A, Dowsett CJ. Replication and robustness in developmental research. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(11):2417–2425. doi: 10.1037/a0037996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer WJ, Day RD, Harper JM. Father involvement: Identifying and predicting family members’ shared and unique perceptions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:516–528. doi: 10.1037/a0036903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley KM, Weisz JR. Child, parent, and therapist (dis)agreement on target problems in outpatient therapy: The therapist’s dilemma and its implications. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):62–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager J. Convergence and nonconvergence in the quality of adolescent relationships and its association with adolescent adjustment and young adult relationship quality. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2011;35:497–506. doi: 10.1177/0165025411422992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager J, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Hendricks C. Family members’ unique perspectives of the family: Examining their scope, size, and relations to individual adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(3):400–410. doi: 10.1037/a0028330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager J, Yuen CX, Bornstein MH, Putnick DL, Hendricks C. The relations of family members’ unique and shared perspectives of family dysfunction to dyad adjustment. Journal of family psychology. 2014;28(3):407–414. doi: 10.1037/a0036809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager J, Yuen CX, Putnick DL, Hendricks C, Bornstein MH. Adolescent-peer relationships, separation and detachment from parents, and internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Linkages and interactions. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2015;35:511–537. doi: 10.1177/0272431614537116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaleque A, Rohner RP. Perceived Parental Acceptance-Rejection and Psychological Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis of Cross-Cultural and Intracultural Studies. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64(1):54–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, De Los Reyes A. Testing informant discrepancies as predictors of early adolescent psychopathology: Why difference scores cannot to you what you want to know and how polynomial regression may. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2013;41:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Weems CF. The equivalence of regression models using difference scores and models using separate scores for each information: Implications for the study of informant discrepancies. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(2):388–397. doi: 10.1037/a0021926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Collins WA. Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 152–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA. Analysis of the multitrait-multimethod matrix by confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112(1):165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D. Adolescent thinking. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 152–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Wittchen H, Höfler M, Fuetsch M, Stein MB, Merikangas KR. Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(9):859–866. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW. Confirmatory factor analyses of multitrait-multimethod data: Many problems and a few solutions. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1989;13(4):335–361. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, van dB. Internalizing and externalizing problems as correlates of self-reported attachment style and perceived parental rearing in normal adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2003;12(2):171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, De Los Reyes A. Discrepancies in adolescents’ and their mothers’ perceptions of the family and adolescent anxiety symptomatology. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2014;14(1):1–18. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2014.870009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelton J, Forehand R. Discrepancy between mother and child perceptions of their relationship: Consequences for adolescents considered within the context of parental divorce. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Putnick DL, Bornstein MH, Lansford JE, Malone PS, Pastorelli C, Skinner AT, … Sorbring E. Perceived mother and father acceptance-rejection predict four unique aspects of child adjustment across nine countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015;56:923–932. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindskopf D. Using phantom and imaginary latent variables to parameterize constraints in linear structural models. Psychometrika. 1984;49(1):37–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02294204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Cournoyer DE. Universals in youths’ perceptions of parental acceptance and rejection: Evidence from factor analyses within eight sociocultural groups. Cross-Cultural Research: The Journal of Comparative Social Science. 1994;28(4):371–383. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP. The parental “acceptance-rejection syndrome”: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. American Psychologist. 2004;59(8):830–840. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP, Khaleque A, Cournoyer DE. Introduction to parental acceptance-rejection theory, methods, evidence, and implications. 2012 Retrieved from http://csiar.uconn.edu//INTRODUCTION-TO-PARENTAL-ACCEPTANCE-3-27-12.pdf.

- Stryker S. Symbolic interaction theory: A review and some suggestions for comparative family research. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1972;3(1):17–32. [Google Scholar]