Abstract

Background

Immunosuppression medications contribute to posttransplant diabetes mellitus in patients and can cause insulin resistance in male rats. Tacrolimus (TAC)-sirolimus (SIR) immunosuppression is also associated with appearance of ovarian cysts in transplant patients. Because insulin resistance is observed in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome, we hypothesized that TAC or SIR may induce reproductive abnormalities.

Methods

We monitored estrus cycles of adult female rats treated daily with TAC, SIR, and combination of TAC-SIR, or diluent (control) for 4 weeks. Animals were then challenged with oral glucose to determine their glucose and insulin responses, killed, and their blood and tissues, including ovaries and uteri harvested.

Results

TAC and TAC-SIR treatments increased mean random glucose concentrations (P<0.05). TAC, SIR, and TAC-SIR treatments also increased the glucose response to oral glucose challenge (P<0.05). The insulin response to glucose was significantly higher in rats treated with SIR compared with TAC (P<0.05). TAC, SIR and TAC-SIR treatments reduced number of estrus cycles (P<0.05). The ovaries were smaller after SIR and TAC-SIR treatment compared with controls. The TAC and TAC-SIR treatment groups had fewer preovulatory follicles. Corpora lutea were present in all groups. Ovarian aromatase expression was reduced in the SIR and TAC-SIR treatment groups. A significant (P<0.05) reduction in uterine size was observed in all treatment groups when compared with controls.

Conclusion

In a model of immunosuppressant-induced hyperglycemia, both TAC and SIR induced reproductive abnormalities in adult female rats, likely through different mechanisms.

Keywords: Immunosuppressants, Insulin resistance, Ovary, Corpus luteum, Polycystic ovary syndrome

Posttransplant diabetes mellitus (PTDM) reduces graft and patient survival after kidney transplant (1, 2). Immunosuppressants have been strongly implicated in the cause of PTDM (3–5). Tacrolimus (TAC) and sirolimus (SIR) are among the most commonly used immunosuppressant drugs for kidney, pancreas, and islet transplantation. Although these immunosuppressants have different mechanisms of action, both are implicated in PTDM. In a previous study, we have shown that both TAC and SIR, individually and in combination, cause hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, suggesting insulin resistance, in normal male Sprague-Dawley rats (6).

Although there is good evidence that pregnancy does not impact graft survival in kidney recipients, fertility rates are lower and decrease more rapidly over time (7, 8). However, the literature is sparse regarding the effects of TAC and SIR on reproductive function. We have previously shown that women who receive a predominantly cyclosporine-based regimen had improved menses initially, although many returned to irregular menses (9). Women who have had organ transplants often have anovulatory cycles, and women treated with TAC and SIR have been reported to develop adnexal masses or clear ovarian cysts and alterations in menstrual cycles (10, 11). In fact, multiple reports of unsuspected adnexal masses have prompted the suggestion that ultrasound be performed before transplant to identify any preexisting lesions that would complicate posttransplant management and treatment (12). Only recently has a possible connection between immunosuppressive therapy and the appearance of post-transplant ovarian cysts been made, that might suggest polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or another cause of reproductive dysfunction (10, 11, 13, 14). SIR has been associated with reversible gonadal dysfunction and infertility in a small cohort of men and women after kidney transplant (15). Animal studies have shown that TAC given to pregnant Wistar rats does not have any toxic effect on mother/embryo (16). The PCOS phenotype is characterized by anovulatory cycles, hyperandrogenism, and infertility and is associated with insulin resistance (17). Although TAC and SIR have been associated with posttransplant diabetes in clinical studies (18–21), and hyperglycemia in our rodent model (6), there is no reported association of hyperglycemia or hyperinsulinemia induced by TAC or SIR with ovarian function or cyst formation.

In summary, TAC and SIR have been shown to contribute to PTDM and have been associated with adnexal masses, ovarian cyst formation, irregular menses, reversible infertility after transplantation (islet, kidney, and pancreas), but no specific mechanisms have been attributed to these changes in reproductive function. We hypothesize that TAC and SIR not only cause insulin resistance but also affect reproductive function in women. Using an animal model of immunosuppressant-induced hyperglycemia, we tested whether TAC or SIR affect the ovaries and uteri in adult female rats.

RESULTS

Body Weight and Insulin and Glucose Homeostasis

The female rats in the SIR and TAC-SIR-treated groups had less weight gain compared with controls, as observed previously with male rats (6) (see Figure A, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/TP/A413; P<0.05). Three of the five rats in the TAC-SIR group died within 16 days of treatment, and the remaining rats in this group were sacrificed on day 22. Random blood glucose measurements in control animals remained less than 100 mg/dL throughout the study (see Figure B, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/TP/A413). In contrast, random blood glucose concentrations (see Figure B, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/TP/A413) were significantly higher (P<0.05) in TAC and TAC-SIR treated groups, as observed previously with male rats (6).

The mean blood glucose concentrations after the oral glucose challenge administered at the end of the study were also significantly higher in animals treated with TAC, SIR and TAC-SIR compared with control (see Figure A, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/TP/A414; P<0.05). After the oral glucose challenge insulin concentrations in female rats treated with TAC were lower than the SIR group (see Figure B, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/TP/A414, P<0.05), but not significantly different than control group.

Reproductive Abnormalities

The controls demonstrated consistent 4-day estrus cycles (Fig. 1A). Rats treated with TAC had periods of prolonged diestrus (10–22 days) beginning 7 to 10 days after starting the treatment (Fig. 1A). Four of the TAC-treated rats experienced 1- to 3-day irregular cycles after prolonged diestrus. Female rats treated with SIR did not stop cycling; however, this group exhibited irregular 3- to 6-day cycles that were asynchronous with other group members (Fig. 1A). The rats treated with TAC-SIR stopped cycling and showed persistent diestrus after only 2 to 4 days of treatment (Fig. 1A). The mean number of estrus cycles was significantly lower in the TAC, SIR and TAC-SIR groups compared with controls (Fig. 1B; P<0.05). Accordingly, the mean length of the estrus cycles was increased by the treatments (Fig. 1C). Mean serum progesterone, estradiol, and testosterone concentrations were not different among the groups of animals at the end of the study (data not shown), presumptively due to fluctuations in estrus cycles at the end of the experiment.

FIGURE 1.

Effects of sirolimus, tacrolimus, and the combination of tacrolimus and sirolimus on estrus cycle patterns. Adult female rats were treated with sirolimus (SIR), tacrolimus (TAC), tacrolimus + sirolimus (TAC-SIR), or diluent (control), administered as daily subcutaneous injections as described in the Methods. (A) Estrus cycle staging of individual animals was determined by daily vaginal swabs. D, diestrus; E, estrus; P, proestrus. (B) The average number of estrus cycles was determined in each group and results are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). (C) The average estrus cycle length was determined and results are presented as mean ± SEM. *P less than 0.05 versus control.

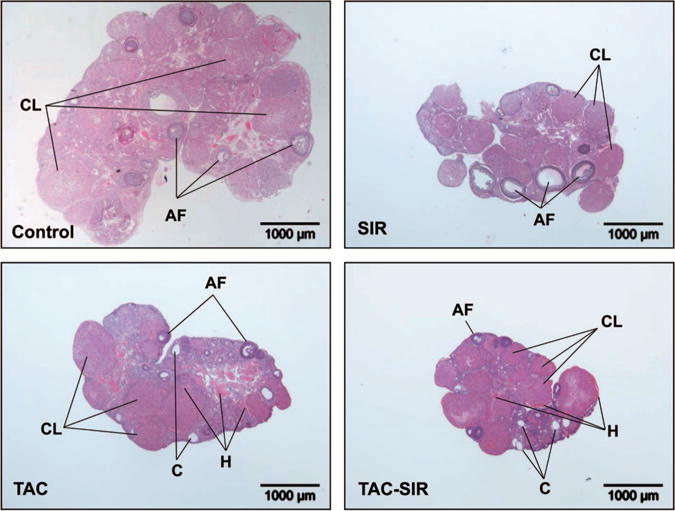

Mean ovarian size (Fig. 2) and weight were reduced in the SIR group compared with the control and TAC groups (mean ± standard error of the mean, n = 5; 22 ± 4.1 mg vs. 31 ± 2.7 mg and 35 ± 13.8 mg, respectively, P<0.05). Ovaries in the control and SIR groups displayed developing and large antral follicles, whereas few large follicles were observed in the TAC-treated groups. Ovaries in the TAC-treated groups also displayed a few small clear cysts and hemorrhagic features. Of interest were the findings that corpora lutea were present in all treatment groups.

FIGURE 2.

Effects of sirolimus, tacrolimus, and the combination of tacrolimus and sirolimus on ovarian morphology. Adult female rats were treated with sirolimus (SIR), tacrolimus (TAC), tacrolimus + sirolimus (TAC-SIR), or diluent (Control), administered as daily subcutaneous injections as described in the Materials and Methods. Ovaries were harvested and fixed in 10% formalin for histology and counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin. AF, antral follicles; CL, corpus luteum; C, cyst; H, hemorrhagic tissue.

Western blot analysis of ovarian homogenates in the control group revealed the presence of aromatase and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD; Fig. 3A), and enzymes required for the synthesis of estrogen and progesterone, respectively. Control ovaries also had detectable levels of phosphorylated p70S6 kinase and its substrate ribosomal protein S6 (S6), providing evidence for mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity. Treatment with SIR, the mTOR inhibitor, reduced phosphorylation of the mTOR targets p70S6 kinase (Fig. 3B) and S6 (Fig. 3C), indicating that SIR was effective at the level of the ovary (Fig. 3, P<0.05). Ovarian aromatase protein levels were 40% lower in the SIR-treated group, which approached statistical significance (P = 0.08; Fig. 3D). The levels of 3β-HSD protein were unchanged after SIR treatment (Fig. 3E). TAC treatment (Fig 4A) did not alter levels of phosphorylated p70S6 kinase (Fig. 4B) or aromatase protein (Fig. 4D). It did, however, increase the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (41%, Fig. 4C) and levels of 3β-HSD protein (30%, Fig. 4E). TAC-SIR treatment inhibited phosphorylated p70S6 kinase (Fig. 4B) and aromatase (Fig. 4D) protein levels. TAC-SIR treatment also prevented the increase in phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 observed on treatment with TAC alone (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of sirolimus on ovarian protein expression. Adult female rats were treated with sirolimus (SIR) or diluent (control). Ovaries were harvested and processed for western blot analysis as described in the Methods. (A) Western blot analysis was performed using antibodies against the phospho-specific p70 S6K (Thr389) and total p70S6K, ribosomal protein S6 and phospho-specific ribosomal protein S6 (Ser235/236), 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), aromatase, and β-actin as aloading control. (B–E) Quantitative analysis of the immunoblot described in (A). Results are expressed as a ratio of phospho-specific protein to total p70S6K (B) or S6 (C) or as a ratio of aromatase (D) or 3β-HSD (E) to β-actin in each ovarian sample. Shown are mean ± standard error of the mean from five animals. *P less than 0.05 versus control.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of tacrolimus and tacrolimus + sirolimus on ovarian protein expression. Adult female rats were treated with tacrolimus (TAC), tacrolimus plus sirolimus (TAC-SIR), or diluent (control). Ovaries were harvested and processed for western blot analysis as described in the Materials and Methods. (A) Western blot analysis was performed using antibodies against the phospho-specific p70 S6K (Thr389) and total p70S6K, ribosomal protein S6 and phospho-specific ribosomal protein S6 (Ser235/236), 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), aromatase, and β-actin as a loading control. (B–E) Quantitative analysis of the immunoblot described in (A). Results are expressed as a ratio of phospho-specific protein to total p70S6K (B) or S6 (C) or as a ratio of aromatase (D) or 3β-HSD (E) to β-actin in each ovarian sample. Shown are means ± standard error of the mean; *P less than 0.05 versus control.

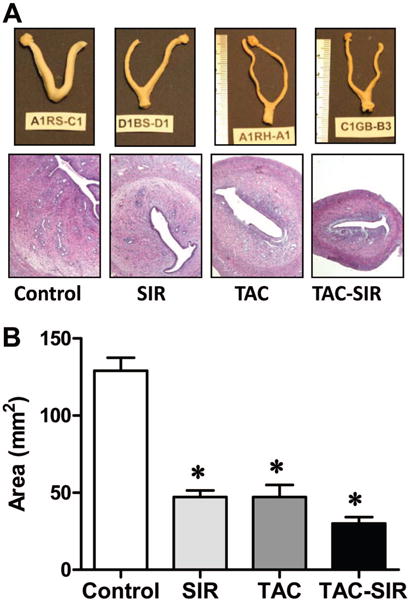

Compared with the control group, uteri were smaller in all treatment groups (Fig. 5A) as indicated by significant reduction (P<0.05) in cross sectional area (Fig. 5B). The uterine luminal epithelium in control animals appeared as a stratified columnar epithelium, whereas, the TAC and SIR groups showed a simpler cuboidal epithelium. Estrogen receptor (ER) α expression was present in the uterine luminal epithelium and glands, and to a lesser extent in the stroma and myometrium in controls (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/TP/A415). A similar pattern was observed in the SIR treated animals, with the exception that the uterine stroma was more intensely stained. In contrast, TAC-treated animals had significantly reduced ER staining in all uterine compartments.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of sirolimus, tacrolimus, and the combination of tacrolimus and sirolimus on uterine morphology. Adult female rats were treated with sirolimus (SIR), tacrolimus (TAC), tacrolimus + sirolimus (TAC-SIR) or diluent (control), administered as daily subcutaneous injections as described in the Methods. (A) Uteri were harvested and fixed in 10% formalin. A segment of the mid portion of each uterine horn was processed for histology and counterstained with hematoxylin-eosin. (B) The cross sectional area was determined and results are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean; *P less than 0.05 versus control.

DISCUSSION

The effect of immunosuppressants on female reproductive function has received little attention, despite their widespread use in various clinical settings. In the present studies, adult female rats treated with TAC, SIR, or the combination of each exhibited abnormalities in the reproductive organs characterized by prolonged estrus cycles, changes in ovarian morphology, and reductions in the size of the uterus with endometrial morphology suggesting a reduction in estrogenic activity. Thus, 1 month of immunosuppressant treatment altered the status of the reproductive organs in female rats. The present findings point to specific changes induced by SIR or TAC, providing new information regarding the potential sites of action of these immunosuppressants on the reproductive axis.

The immunosuppressant medications used in the present study with female rats resulted in hyperglycemia. However, our findings suggest that the mechanisms by which the immunosuppressants exert their effects on insulin and glucose disposition are different. TAC-treated females displayed elevated serum glucose; whereas, SIR-treated females displayed normal serum glucose during the study. Additionally, during the oral glucose tolerance test performed at the end of the study both groups had a hyperglycemic response, but, hyperinsulinemia was observed only in the SIR group. These findings are consistent with our previous experiments evaluating the actions of TAC and SIR, individually and in combination with normal male Sprague-Dawley rats (6) and observations in immunosuppressant-treated posttransplant patients (3–5). Because TAC-SIR immunosuppression is also associated with appearance of ovarian cysts in transplant patients (10, 12) and insulin resistance is observed in patients with PCOS, we hypothesized that TAC or SIR may induce reproductive abnormalities. Indeed, notable changes were observed in estrous cycle length in response to SIR and TAC, with TAC treatment having more profound inhibitory effects. TAC treatment also resulted in a reduction in the large ovarian follicles and the presence of a modest number of small cyst-like structures. Rats treated with a combination of SIR-TAC resulted in a reduction in developing follicles and appearance of small ovarian cysts. Further studies are needed to determine whether the immunosuppressant-induced changes in insulin and glucose homeostasis contribute to observed alterations in reproductive cycles and ovarian morphology or if the reproductive effects are independent of immunosuppressant-induced changes in metabolic status.

SIR induced hyperinsulinemia compared with TAC in our female rat model. Hyperinsulinemia with accompanying hyperandrogenemia is an important part of pathophysiology of irregular menstrual cycles in women with PCOS (17). Likewise, the SIR-treated group exhibited irregular estrus cycles, suggesting hyperandrogenemia as a possible mechanism. However, analysis of serum testosterone levels at the end of the study revealed no differences among groups. In fact, serum concentrations of testosterone, estradiol, and progesterone were not statistically different among all groups at the time of sacrifice, which is likely attributed to the disruption of synchronous estrous cycles by the immunosuppressants. SIR has been shown to lower testosterone in male transplant patients, with primary gonadal effect as the cause (15, 22–24). Studies in female transplant patients, however, have displayed normal estradiol levels along with irregular menstrual cycles, more consistent with our findings, although the mechanism is unclear (10). SIR has also been associated with reversible gonadal dysfunction and infertility in both male and female kidney transplant recipients (15). Recent studies in immature rats provide biochemical evidence that inhibition of the mTOR pathway may disrupt fertility. The mTOR pathway seems to be required for follicle-stimulating hormone-mediated proliferation of granulosa cells (25) and the induction of markers of ovarian follicle differentiation, including induction of the luteinizing-hormone receptor, inhibin-alpha, and the protein kinase A type IIβ regulatory subunit (26). However, the inhibition of mTOR did not impair progesterone secretion by primary cultures of ovarian corpus luteum cells, suggesting that mTOR may have a greater impact on processes involved in ovarian follicle growth and differentiation than progesterone synthesis per se (27). The present study showing that ovarian size and aromatase expression in adult rats were reduced after 4 weeks of treatment with the mTOR inhibitor SIR extends our current understanding of the events that lead to the disruption of fertility. Other recent studies suggest that deregulation of tuberosclerosis/mTOR and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) signaling pathways in oocytes may have implications in premature ovarian failure and infertility (28). At present, it seems unlikely that these phenomena are directly related to impaired glycemic control as all three treatment groups were hyperglycemic but had different effects on ovarian histology and estrus cycles.

An interesting observation in this study was the presence of corpora lutea in all treatment groups despite the long interval between estrus cycles in the TAC-treated animals. The corpus luteum plays a central role in the regulation of ovarian cyclicity and the maintenance of pregnancy, events which are mediated by progesterone (29). In rodents, the induction of 20α-HSD is required to convert progesterone to an inactive metabolite to initiate parturition (30). Calcium/calmodulin inhibitors have been shown to decrease the expression of 20α-HSD in rat luteal cells (29). Of relevance to this study are the facts that calcineurin is a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent serine-threonine protein phosphatase (31, 32) and that TAC, a calcineurin inhibitor, has been shown to delay parturition in mice (33). Taken together, these observations suggest that TAC potentially inhibits the expression of 20α-HSD, thus preventing the degradation of progesterone, extending the life of the corpus luteum and disrupting of the normal pattern of estrus cycles seen in our experiments. This idea is supported by the presence of persistent corpora lutea in females treated with TAC and the combination of TAC and SIR.

A number of differences were noted in the effects of TAC or SIR in adult female rats. Because it is well established that TAC and SIR have distinct cellular mechanisms of action differences in physiologic or cellular responses are to be expected. In this regard, only the SIR-treated animals experienced less weight gain over the 4-week treatment protocol compared with the control group, whereas remaining euglycemic as determined by random blood sampling during the treatment phase. Second, SIR but not TAC induced hyperinsulinemia. In fact, TAC reduced insulin secretion. The results suggest that TAC impairs islet cell function and SIR impairs insulin sensitivity, with both treatments having a common impact on the disposal of glucose. Differences were also noted in reproductive function. SIR but not TAC treatment reduced ovarian weights and aromatase expression. TAC but not SIR reduced ERα expression in the uterine stromal and luminal epithelium. The different responses to both treatments could result in a common impact on estrogenic activity at the level of the uterus, which could account for the SIR- and TAC-induced reductions in uterine size.

Plasma levels of TAC and SIR were higher in our study with female rats than the usual clinical targets and compared with previous studies of male rats treated for 2 weeks with the same immunosuppressant doses (6). The cause of death in the TAC-SIR group was likely due to the toxicity of the immunosuppressants as they were given 4 weeks as opposed to 2 weeks in our previous experiments (6). The longer duration of treatment could allow greater accumulation of drug than previous studies and the lipophilic character of these medications (34), resulting in slower metabolism in female rats, which have a higher percentage of body fat than males. Nonetheless, the changes occurred soon after treatment initiation, suggesting that the drugs have effects at lower concentrations, more consistent with their clinical application. Although the concentrations of immunosuppressants were higher in our study with female rats than typically experienced following their use clinically, these studies suggest that both drugs affect the ovary and uterus whether or not related to the onset of insulin resistance, and further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms.

The limitations of our study include (1) relatively small study; (2) selection of a specific treatment duration rather than a specific stage in the estrus cycle as the end point for this study. This was not as critical for the animals treated with TAC because it disrupted normal cyclicity. A larger sample size would enable ovarian and uterine endpoints to be better correlated with a specific stage of the estrous cycle in the SIR groups; and (3) the concentrations of immunosuppressants achieved were higher than those commonly seen in human transplant patients, but this study still serves as a proof of concept.

In conclusion, although both immunosuppressant medications induced reproductive abnormalities, TAC was more likely to disrupt normal estrus cycles than SIR. The present findings point to specific changes induced by SIR or TAC, providing new information regarding the potential of these immunosuppressants to disrupt reproductive potential. Future studies are required to assess the effect of TAC and SIR on fertility and pregnancy outcomes. This information can be used to design new approaches for coordinating the reproductive axis and identifying ways to circumvent the detrimental side effects of these agents in female patients who wish to maintain fertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Care

Animal use was approved by the Subcommittee of Animal Studies and Research and Development Committee, Omaha VA Medical Center, NE. Adult, female Sprague-Dawley rats (150–200 g) were kept under 12-hr dark and light periods and fed standard laboratory chow except before fasting samples when food but not water was removed for 12 hr. Rats were re-housed into four groups (n = 5 per group) based on their individual pattern of estrus cycling identified in each individual rat, before initiating treatment. Vaginal swabs were obtained daily to ascertain estrus cycle stage for 2 weeks before assignment of treatment groups and were continued throughout the experiment (35).

Experimental Design

Rats in each group were given daily subcutaneous injections of one of the following treatments for 4 weeks: (1) two injections of diluent (sunflower oil/10% ethanol) as control, (2) TAC alone (4 mg/kg/day; LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA)+control solution, (3) SIR alone (2 mg/kg/day; LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA)+control solution, or (4) separate injections of TAC and SIR at the above dosages. Drug dosages were chosen based on previously published dose response curves (6). Researchers were blinded to treatment assignment until after the experiment was completed.

Daily weights were recorded, and nonfasting blood glucose concentrations were measured using a glucose meter (Freestyle; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) twice a week. Vaginal swabs were obtained daily to ascertain estrus cycle stage (35).

Food was withheld the night before the last day when an oral glucose challenge was administered by gavage (1 g/kg) as previously described (6). Tail vein blood was collected at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after glucose administration for determination of glucose and insulin concentrations. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture at time of sacrifice for immunosuppressant and hormone concentrations. Uteri and ovaries were harvested and fixed in 10% formalin for histology and counterstained with hematoxylineosin. Ovarian weights and uterine crosssectional areas were quantified.

Insulin, Immunosuppressant, and Hormone Concentrations

Plasma insulin concentration was measured by radioimmunoassay (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO) using an assay with sensitivity of 0.1 ng/mL, and 0% cross reactivity with proinsulin. TAC and SIR concentrations were performed on whole blood samples by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry 24 hr after last injection specimens by the Clinical Laboratory of the Nebraska Medical Center (36) as detailed in the Supplemental Methods (see Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/TP/A416).

Western blot analysis of ovarian proteins was performed as previously described (27) and detailed in the Supplemental Methods (see Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/TP/A416).

Detection of ERα: ERα was detected by immunohistochemistry with an Invitrogen 3rd Gen IHC detection kit (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) as detailed in Supplemental Methods (see Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/TP/A416).

Statistical Analyses

Data are represented as mean±standard error of the mean. Changes in glucose and insulin over time after glucose administration were calculated as area under the curve. Area under the curve for all groups was compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Glucose and insulin changes were also measured by two-way ANOVA. Ovarian weights, uterine cross-sectional areas, steroid hormone concentrations, and ERα staining patterns were compared between treatment groups by one-way ANOVA. Dunnett’s posttest was used for posthoc testing; P less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the secretarial assistance of Christine Nystrom and Pamela Welch.

This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Merit Review Research Program (J.S.D.), the Olson Center for Women’s Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (J.S.D.), and a University of Nebraska Medical Center Assistantship (D.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

J.L., J.S.D., and F.G.H. participated in research design; V.S., J.S.D., J.L., and F.G.H. participated in writing of the manuscript; J.L., L.O., D.M., C.W., J.P., and C.E.C. participated in the performance of the research; and J.L., V.S., J.S.D., D.M., and C.W. participated in data analysis.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.transplantjournal.com).

References

- 1.Davidson J, Wilkinson A, Dantal J, et al. New-onset diabetes after transplantation: 2003 International consensus guidelines. Transplantation; Proceedings of an international expert panel meeting; Barcelona, Spain. 19 February 2003; 2003. p. SS3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, Leivestad T, et al. The impact of early-diagnosed new-onset post-transplantation diabetes mellitus on survival and major cardiac events. Kidney Int. 2006;69:588. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato T, Inagaki A, Uchida K, et al. Diabetes mellitus after transplant: Relationship to pretransplant glucose metabolism and tacrolimus or cyclosporine A-based therapy. Transplantation. 2003;76:1320. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000084295.67371.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulanc E, Lane JT, Puumala SE, et al. New-onset diabetes after kidney transplantation: An application of 2003 International Guidelines. Transplantation. 2005;80:945. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000176482.63122.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penfornis A, Kury-Paulin S. Immunosuppressive drug-induced diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32(5 pt 2):539. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(06)72809-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen JL, Bennett RG, Burkman T, et al. Tacrolimus and sirolimus cause insulin resistance in normal Sprague Dawley rats. Transplantation. 2006;82:466. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000229384.22217.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levidiotis V, Chang S, McDonald S. Pregnancy and maternal outcomes among kidney transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2433. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill JS, Zalunardo N, Rose C, et al. The pregnancy rate and live birth rate in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack-Shipman LR, Ratanasuwan T, Leone JP, et al. Reproductive hormones after pancreas transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;70:1180. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200010270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cure P, Pileggi A, Froud T. Alterations of the female reproductive system in recipients of islet grafts. Transplantation. 2004;78:1576. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000147301.41864.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfadhli E, Koh A, Albaker W, et al. High prevalence of ovarian cysts in premenopausal women receiving sirolimus and tacrolimus after clinical islet transplantation. Transpl Int. 2009;22:622. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaughan R, Henderson SC, Rahatzad M, et al. Unsuspected adnexal masses in renal transplant recipients. J Urol. 1982;128:1017. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)53324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaber AO, Kahan BD, Van Buren C, et al. Comparison of sirolimus plus tacrolimus versus sirolimus plus cyclosporine in high-risk renal allograft recipients: Results from an open-label, randomized trial. Transplantation. 2008;86:1187. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318187bab0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, et al. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2005;54:2060. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boobes Y, Bernieh B, Saadi H, et al. Gonadal dysfunction and infertility in kidney transplant patients receiving sirolimus. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42:493. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramos AF, Rodrigues JK, da Silva LR, et al. Embryo development in rats treated with tacrolimus during the preimplantation phase. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2008;30:219. doi: 10.1590/s0100-72032008000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Hum Reprod. 2004;(19):41. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodward RS, Schnitzler MA, Baty J, et al. Incidence and cost of new onset diabetes mellitus among U.S. wait-listed and transplanted renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:590. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porrini E, Moreno JM, Osuna A, et al. Prediabetes in patients receiving tacrolimus in the first year after kidney transplantation: A prospective and multicenter study. Transplantation. 2008;85:1133. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816b16bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston O, Rose CL, Webster AC, et al. Sirolimus is associated with new-onset diabetes in kidney transplant recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1411. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007111202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakeam HA, Al-Jedai AH, Raza SM, et al. Sirolimus induced dyslipidemia in tacrolimus based vs. tacrolimus free immunosuppressive regimens in renal transplant recipients. Ann Transplant. 2008;13:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huyghe E, Zairi A, Nohra J, et al. Gonadal impact of target of rapamycin inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus) in male patients: An overview. Transpl Int. 2007;20:305. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tondolo V, Citterio F, Panocchia N, et al. Gonadal function and immunosuppressive therapy after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1915. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Coco M, Greenstein SM, et al. The effect of sirolimus on sex hormone levels of male renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2005;19:162. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kayampilly PP, Menon KM. Follicle-stimulating hormone increases tuberin phosphorylation and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling through an extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent pathway in rat granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3950. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alam H, Maizels ET, Park Y, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is necessary for induction of select protein markers of follicular differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19431. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401235200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou X, Arvisais EW, Davis JS. Luteinizing hormone stimulates mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in bovine luteal cells via pathways independent of AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase: Modulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and AMP-activated protein kinase. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2846. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adhikari D, Zheng W, Shen Y, et al. Tsc/mTORC1 signaling in oocytes governs the quiescence and activation of primordial follicles. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:397. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stocco CO, Lau LF, Gibori G. A calcium/calmodulin-dependent activation of ERK1/2 mediates JunD phosphorylation and induction of nur77 and 20alpha-hsd genes by prostaglandin F2alpha in ovarian cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stocco CO, Zhong L, Sugimoto Y, et al. Prostaglandin F2alpha-induced expression of 20alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase involves the transcription factor NUR77. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rusnak F, Mertz P. Calcineurin: Form and function. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1483. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Rossum HH, de Fijter JW, van Pelt J. Pharmacodynamic monitoring of calcineurin inhibition therapy: Principles, performance, and perspectives. Ther Drug Monit. 2010;32:3. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181c0eecb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabata C, Ogita K, Sato K, et al. Calcineurin/NFAT pathway: A novel regulator of parturition. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2009;62:44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cattaneo D, Perico N, Remuzzi G. From pharmacokinetics to pharmacogenomics: A new approach to tailor immunosuppressive therapy. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hubscher CH, Brooks DL, Johnson JR. A quantitative method for assessing stages of the rat estrous cycle. Biotech Histochem. 2005;80:79. doi: 10.1080/10520290500138422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volosov A, Napoli KL, Soldin SJ. Simultaneous simple and fast quantification of three major immunosuppressants by liquid chromatography—Tandem mass-spectrometry. Clin Biochem. 2001;34:285. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(01)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.