Abstract

Phage-display libraries and DNA-encoded chemical libraries (DECL) represent useful tools for the isolation of specific binding molecules out of large combinatorial sets of compounds. In both methods, specific binders are recovered at the end of affinity capture procedures, using target proteins of interest immobilized on a solid support. However, while the efficiency of phage-display selections is routinely quantified by counting the phage titer before and after the affinity capture step, no similar quantification procedures have been reported for the characterization of DNA-encoded chemical library selections. In this article, we describe the potential and limitations of quantitative PCR (qPCR) methods for the evaluation of selection efficiency, using a combinatorial chemical library with more than 35 million compounds. In the experimental conditions chosen for the selections, a quantification of DNA input/recovery over five orders of magnitude could be performed, revealing a successful enrichment of abundant binders, which could be confirmed by DNA sequencing. qPCR provides rapid information about the performance of selections, thus facilitating the optimization of experimental conditions.

Keywords: DNA-encoded chemical libraries, qPCR, quantification, selection

Introduction

The construction of large combinatorial libraries of polypeptides, containing billions of distinct compounds, has revolutionized the way therapeutic proteins are discovered, which are specific to biological targets of interest.[1] The isolation of specific binders is greatly facilitated by the implementation of suitable selection methods, which allow the recovery, amplification and identification of binding molecules with the desired binding characteristics. For example, the display of antibodies on the surface of filamentous phage (a bacterial virus) has allowed the construction of combinatorial libraries containing billions of different specificities, from which monoclonal antibodies against virtually any target of interest can be isolated.[2] The technology relies on the intimate coupling of a binding property (“phenotype”), corresponding to the molecular features of a suitable monoclonal antibody on the surface of filamentous phage, with the DNA sequence that codes for the antibody molecule (“genotype”).

In full analogy to phage-display libraries of polypeptides, large combinatorial collections of chemical compounds can be constructed and screened, using DNA fragments as amplifiable identification barcodes.[3] In this case, individual molecules may embody a binding “phenotype”, which is intimately connected to distinctive DNA fragments, which enable the identification of the small molecule to which they are attached, by PCR amplification and high-throughput DNA sequencing.[4]

In both antibody-phage display technology and DNA-encoded chemical libraries, selections are performed by incubation of the library with a target protein of interest, immobilized on a solid support. In the case of phage display libraries, it is common practice to measure the titer of the library before and after selection, by infecting bacteria with the phage particles and by counting the resulting colonies. The number of colonies, which grow on a selective medium, corresponds to the number of phage particles.[2a] One normally uses ~1013 phage particles in a given selection, with libraries which may contain 109-1011 different members (i.e., 102-104 copies of each compound), recovering anything between 104 and 108 phage particles, depending on the experimental conditions and on the frequency of specific binders in the library.[5] Multiple rounds of panning and phage amplification are routinely performed, in order to identify monoclonal antibodies with specific binding properties for the antigen of interest. While ELISA methodologies provide the desired information regarding the antigen binding specificity and performance of individual monoclonal antibodies, the monitoring of phage titers before and after selection provides important information about the selections (e.g., background levels, progressive enrichment after successive rounds of panning). [6]

When using DNA-encoded chemical libraries, one normally performs a single round of panning, as the DNA fragment does not biosynthetically encode the corresponding compound, but merely serves as identification barcode. In most cases, 105-108 copies of individual compounds in the library are used in selection procedures.[7] The fingerprints, which are obtained comparing the DNA sequencing of the library before and after selection, are highly predictive for the identification of specific binding molecules and, to some extent, for their binding affinity to the target.[8] Nonetheless, it is desirable to quantify the amount of DNA before and after selections, as this information can shed light on important experimental parameters, such as the “stickiness” of the library on the solid support and the recovery efficiency.

Here, we describe the use of qPCR for the evaluation of the DNA content of an encoded library, before and after selection on a target protein of interest, immobilized on a solid support. qPCR has previously been used for the quantification of DNA selections on model compounds but to the best of our knowledge, not for the characterization of library selections. We performed our experiments using a combinatorial library, containing 35’393’112 macrocyclic derivatives, constructed using three sets of building blocks. The library construction will be described elsewhere but, for the purpose of this study, it is important to mention that one of the three sets of building blocks contains acetazolamide (a single-digit nanomolar binder to carbonic anhydrase IX) [9] at a frequency of 1 molecule out of 324 compounds (0.3 %). In representative experimental conditions, a quantification of DNA input/recovery over five orders of magnitude could be performed, revealing a successful enrichment of abundant specific binders, which could be confirmed by DNA sequencing. Furthermore, the results indicate whether certain experimental parameters should be optimized, in order to facilitate the detection of rare binders.

Results and Discussion

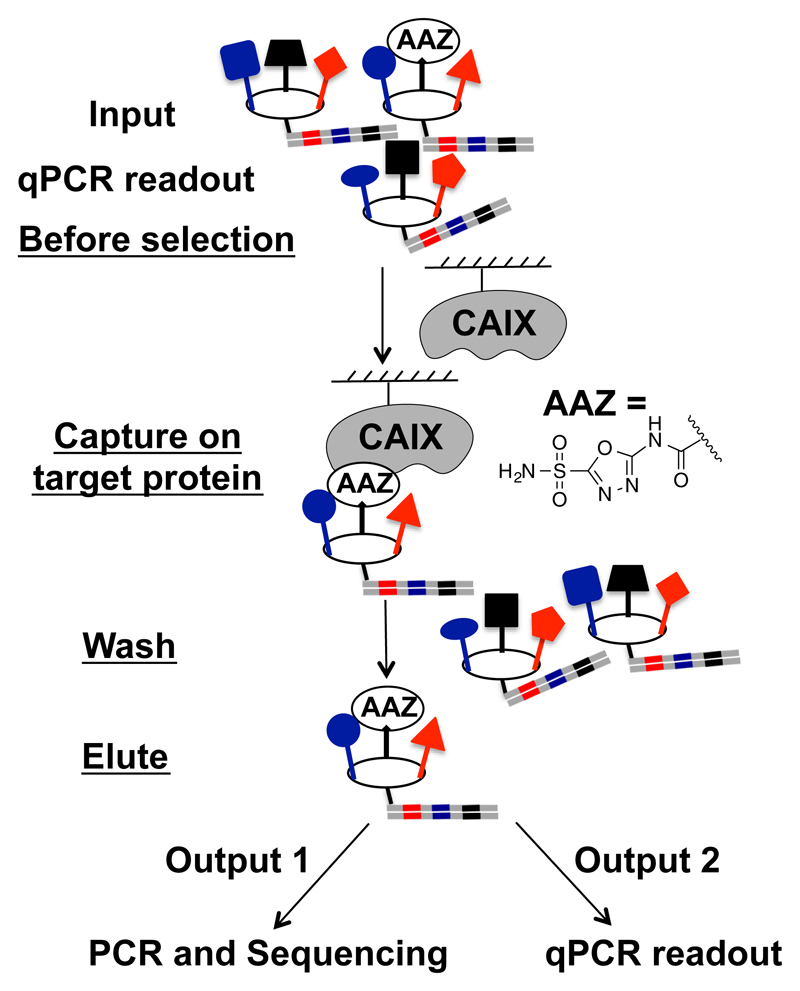

The experimental methodology used in this study is depicted in Figure 1. A library of macrocycles, constructed using three sets of building blocks (283 × 386 × 324 = 35’393’112 compounds) was used as input for selection procedures on solid support. One of the three sets of building blocks contained acetazolamide (a single-digit nanomolar binder to carbonic anhydrase IX) at a frequency of 1 molecule out of 324 compounds, thus facilitating the calculation of theoretical and experimental DNA recovery against this protein. The DNA fragments, which were recovered after suitable washing steps, were amplified by PCR and submitted to high-throughput DNA sequencing. In parallel, the total quantity of DNA was assessed using a qPCR procedure.

Figure 1.

A library of 35’393’112 macrocycles containing an acetazolamide diversity element at 0.3% of total members was used as model system for selections against carbonic anhydrase IX. The recovered DNA fragments were read-out by high-throughput DNA sequencing or by qPCR.

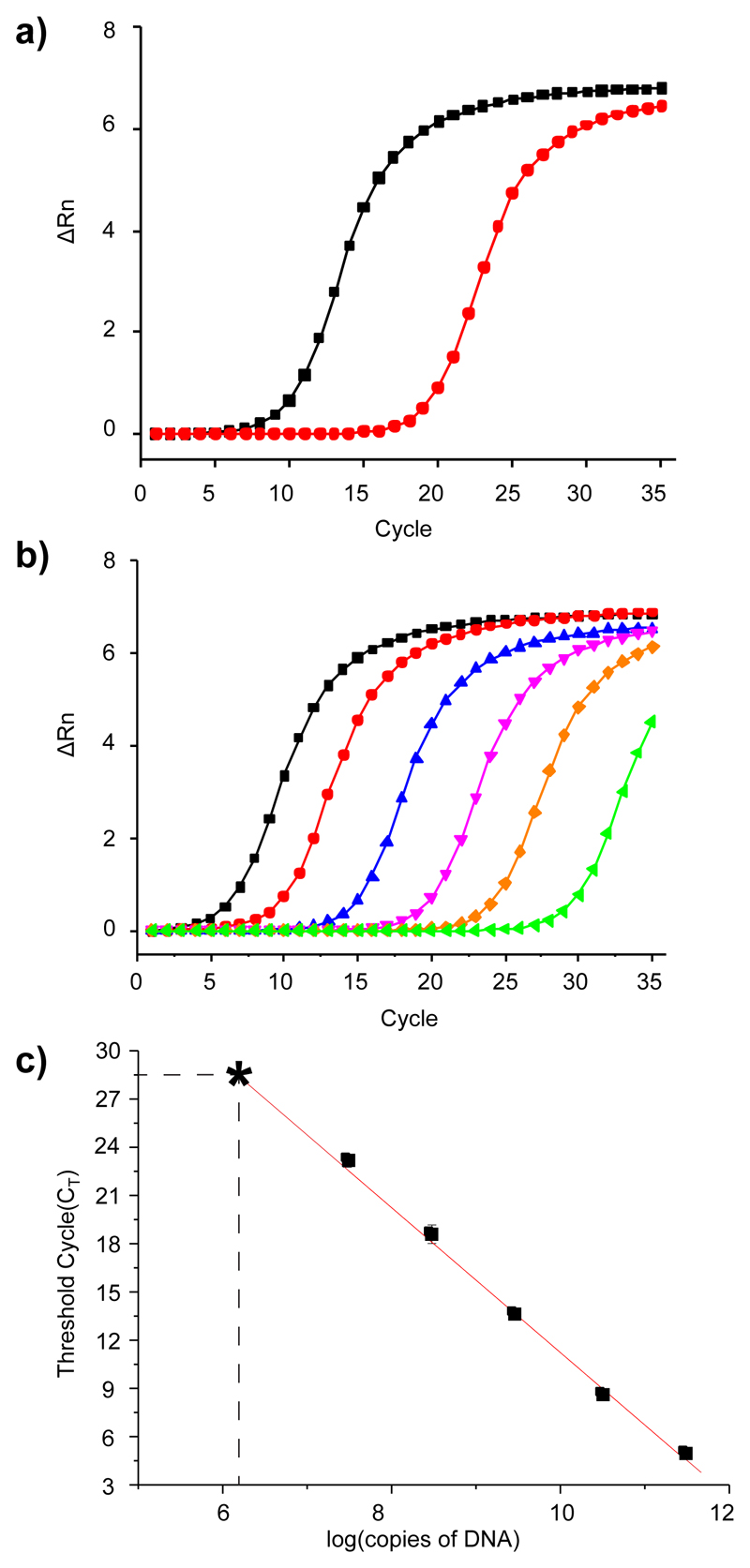

Figure 2a) shows a representative qPCR profile, obtained using DNA fragments recovered after selection on carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) or on magnetic beads, which had not been coated with a target protein. The CAIX selection led to the generation of a detectable initiation of amplification signal in the qPCR procedure after 9 cycles, while the negative control selection (streptavidin-coated beads without target protein) did reach the same threshold after 19 cycles. Figure 2b) shows a similar analysis, which was performed on different amounts of the input library (quantified as nominal concentration of total DNA), together with the amplification of a reaction mixture without template input. In the latter case, the initiation of amplification signal was detected after 28 cycles. Such signal, which typically arises from the formation of primer dimers, [10] rather than products of template amplification, determines the ultimate dynamic range of qPCR detection. The results of Figure 2b) could be used to create a calibration curve, which is depicted in Figure 2c) and which enabled the comparative evaluation of DNA recovery in various selections.

Figure 2.

a) qPCR analysis of a selection against CAIX (black curve) and empty beads without protein (red curve). b) qPCR analysis of a library serial dilution (black: 3.0 × 1011 copies, red: 3.0 × 1010 copies, blue: 3.0 × 109 copies, magenta: 3.0 × 108 copies, orange: 3.0 × 107 copies and green: without template DNA input). c) Calibration curve. The asterisk denominates a nominal amount of DNA obtained in the absence of template, which corresponded to the formation of primer dimers and ultimately determines the noise of the detection procedure.

Table 1 displays the results of twelve selection experiments, performed using three biotinylated proteins (carbonic anhydrase IX, human serum albumin and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein) as target antigens, immobilized on M-270, M-280, T1 or C1 streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. The M-280 and T1 beads had been blocked with BSA, while the others were without blocking agent. One experiment (Entry 7) was performed on “empty” streptavidin-coated beads, where no biotinylated target protein had been used. The amounts of beads used for the selections corresponded to a nominal binding capacity of 6 × 1012 (M-270 and M-280) and 1.2 × 1013 molecules of biotinylated protein (T1 and C1). The amount of biotinylated CAIX, which varied between 1.2 × 1013 and 1.2 × 1014 molecules, was thus always greater than the theoretical binding capacity of the magnetic beads. Due to bead saturation, the different amounts of biotinylated CAIX did not influence selection results (Entry 2, 4, 5 and 6). As 0.3% of the library consisted of macrocycles, containing acetazolamide as one set of building blocks, it is reasonable to estimate that the corresponding amount of DNA could be recovered in ideal selection conditions. Indeed, inspection of the fraction of DNA sequences that corresponded to the acetazolamide-containing molecules revealed that the recovery of AAZ derivatives was less than 1% when CAIX had been omitted or replaced by other target proteins (Entry 7, 8 and 9). By contrast, the frequency of AAZ-containing ligands was always > 30% (and typically >60%), when selections were performed on CAIX-coated beads. Interestingly, the lowest enrichment of CAIX binders (31%) was observed when the lowest amount of library input was used (Entry 3) (corresponding to 1.9 × 105 copies of each molecule in the library before selection). By contrast, in these experiments, the different types of beads did not dramatically change selection results (Entry 2, 10, 11 and 12).

Table 1.

qPCR-based quantification of the DNA output from different selections.

| Entry | Input/copies[a] | Beads[b] | Target/copies | Output/copies[c] | %AAZ[d] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 × 1014 | M-270 | 1.8 × 1013[e] | 7.9 × 1010 | 74 |

| 2 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-270 | 1.8 × 1013[e] | 3.8 × 1010 | 61 |

| 3 | 6.9 × 1012 | M-270 | 1.8 × 1013[e] | 7.5 × 109 | 31 |

| 4 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-270 | 1.2 × 1014[e] | 3.9 × 1010 | 68 |

| 5 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-270 | 4.7 × 1013[e] | 3.5 × 1010 | 65 |

| 6 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-270 | 1.2 × 1013[e] | 3.0 × 1010 | 65 |

| 7 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-270 | 0[f] | 2.1 × 108 | 0.26 |

| 8 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-270 | 1.8 × 1013[g] | 4.9 × 108 | 0.12 |

| 9 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-270 | 1.8 × 1013[h] | 2.1 × 108 | 0.20 |

| 10 | 3.5 × 1013 | M-280 | 1.8 × 1013[e] | 3.8 × 1010 | 68 |

| 11 | 3.5 × 1013 | T1 | 1.8 × 1013[e] | 3.2 × 1010 | 66 |

| 12 | 3.5 × 1013 | C1 | 1.8 × 1013[e] | 3.5 × 1010 | 58 |

The amount of DNA input was quantified by absorption at 260 nm.

The capacity of beads was calculated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The amount of DNA output is read-out by triplicate qPCR measurement.

The fraction of the acetazolamide-containing binders (%AAZ) is calculated by Equation (1) (see Experimental Section).

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX).

Streptavidin-coated beads only

Human serum albumin (HSA).

Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (AGP). Parameters varied in the selections are highlighted in grey.

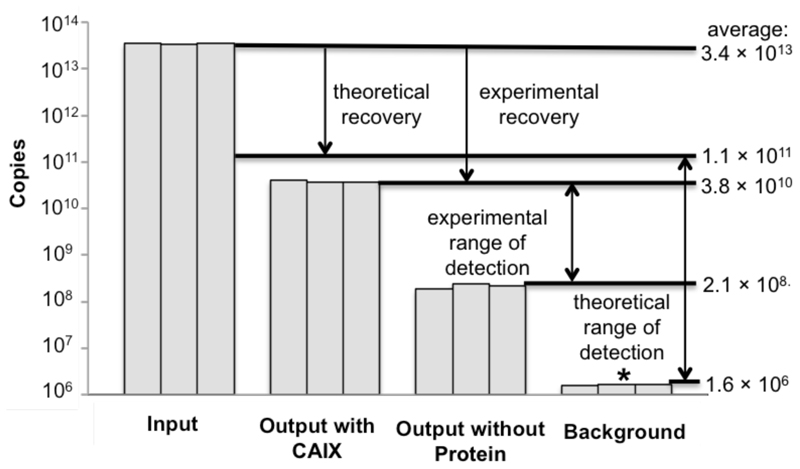

Some of the results displayed in Table 1 can be summarized as depicted in Figure 3. A total of 3.4 × 1013 molecules of DNA were used as input, of which ~ 1.1 × 1011 molecules represented putative CAIX binders. In an experiment performed in triplicate, approximately 34% of the maximum theoretical portion of the library, predicted to bind to CAIX, was recovered. 61% of the DNA fragments, amplified at the end of the selection, corresponded to acetazolamide-containing molecules (Table 1, Entry 2). By contrast, the DNA quantity in selections performed without CAIX corresponded to an output of 2.1 × 108 molecules of DNA. The ultimate “noise” for the qPCR monitoring of selection procedures corresponds to a nominal amount of 1.6 × 106 DNA copies, derived from primer dimers formation. The Figure illustrates that a theoretical range of qPCR detection of five orders of magnitude could in principle be possible. In practical selections, certain experimental conditions (e.g., stringency of washing, “stickiness” of the target protein) may limit the dynamic range of the procedure and the detection of rare binders within the library.[11] The qPCR methodology provides a rapid diagnostic test for the quality of the selections and facilitates changes to the experimental conditions, before the expensive DNA sequencing step is performed. Quantitative PCR readouts nicely complement the information, which is contained in the selection fingerprints, obtained by high-throughput sequencing of library member DNA codes, before and after panning

Figure 3.

qPCR-based triplicate quantification of DNA-encoded chemical library at various steps of a selection procedure. The DNA quantity of the library drops after CAIX selection to levels, which are close to the theoretical recovery limit. In this experiment, a background at 2.1 × 108 copies of DNA was observed, when performing selections in the absence of CAIX. The ultimate noise of the procedure, determined by the formation of primer dimers, corresponds to the formation of 1.6 × 106 nominal copies of DNA (asterisk). Thus, the dynamic range of qPCR detection in library selections is influenced by experimental parameters (e.g., stringency of washing), which can be optimized prior to the expensive step of high-throughput DNA sequencing.

Experimental Section

Materials

Unless otherwise noted, all reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received. Water was purified with a Thermo Scientific Barnstead Nanopure system. Oligonucleotides were purchased from DNA Technology (Denmark). Dynabeads M270 Streptavidin, M280 Streptavidin, MyOneTM streptavidin T1 and MyOneTM streptavidin C1 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. 65801). Herring sperm DNA wwas purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. 15634-017). KingFisher magnetic particle processor was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (cat. no. 5400000).

Selection against target proteins

Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (10 μL of suspension) were suspended in PBS (50 mM sodium phosphate and 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 100 μL). Using a KingFisher magnetic particle processor, the magnetic beads were transferred to a solution PBS of biotinylated targets (CAIX, HSA and AGP; 0 copies, 1.2 × 1013 copies, 1.8 × 1013 copies, 4.7 × 1013 copies and 1.2 × 1014 copies, 100 μL) and incubated for 30 min with continuous gentle mixing. The beads were washed (2 × 3 min, 200 μL) with PBST-B (50 mM sodium phosphate and 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 0.25 % Tween-20, biotin: 100 μM, 200 μL) to block free streptavidin binding sites and washed (1 × 3 min) with PBST (50 mM sodium phosphate and 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 0.25 % Tween-20, 200 μL). The protein-loaded beads were transferred to a solution of the DECL (6.9 × 1012 copies, 3.5 × 1013 copies and 1.0 × 1014 copies, 50 mM sodium phosphate and 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, 0.25 % Tween-20, 300 μg/mL Herring sperm DNA, 100 μL) and the suspension incubated for 1 h with continuous gentle mixing. The beads were removed and washed with PBST (5 × 30 s) and incubated with elution buffer (Buffer EB; Qiagen, 100 μL). DNA conjugates were released by heat denaturation of the proteins (96 °C for 10 min).

The elutes were amplified by PCR after selection experiments and submitted to the Functional Genomics Center Zurich for high-throughput DNA sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2500.

The fraction of the acetazolamide-containing binder (%AAZ) was calculated as Equation (1):

SC(x,y,AAZ): sequence count (X and y define the number of the building block at two sets, the third set is acetazolamide). SC(u,v,w): sequence count (u,v and w define the number of the building block at three sets)

qPCR analysis of DNA recovery from selection against target proteins

qPCR was carried out using the StepOnePlus® Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). In a Fast Optical 96 well reaction plate (Applied Biosystems) were combined to a total volume of 20 μL: 2 μL DNA template (selection eluate or water as blank), 250 nM forward primer (5 pmol in 2 μL of water), 250 nM reverse primer (5 pmol in 2 μL of water), 10 μL PowerUpTM SYBR® Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. 100031508) and 4 μL water. All qPCR experiments performed using SYBR Green were conducted at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, and then 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s (denature), 60°C for 1 min (anneal/extend). The specificity of the reactions was verified by melt curve analysis.

Forward primer: GGAGCTTCTGAATTCTGTGTG

Reverse primer: GCTCTGCACGGTCGC

Acknowledgements

We thank Davor Bajic for technical support and Prof. Gisbert Schneider for access to instruments. Funding from the ETH Zürich, the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030B_163479/1 Grant and CRSII2_160699/1 Sinergia Grant), from the ERC Advanced Grant “Zauberkugel” and from Philochem AG is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- [1].a) Lowman HB, Bass SH, Simpson N, Wells JA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10832–10838. doi: 10.1021/bi00109a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Heinis C, Winter G. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2015;26:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lerner RA. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:498–508. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) McCafferty J, Griffiths AD, Winter G, Chiswell DJ. Nature. 1990;348:552–554. doi: 10.1038/348552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lerner R, Kang A, Bain J, Burton D, Barbas C. Science. 1992;258:1313–1314. doi: 10.1126/science.1455226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Barbas CF, III, Amberg W, Simoncsits A, Jones TM, Lerner RA. Gene. 1993;137:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90251-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Brenner S, Lerner RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5381–5383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kleiner RE, Dumelin CE, Liu DR. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5707–5717. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15076f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li G, Zheng W, Liu Y, Li X. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2015;26:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Franzini RM, Randolph C. J Med Chem. 2016;59:6629–6644. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zimmermann G, Neri D. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21:1828–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Mannocci L, Zhang Y, Scheuermann J, Leimbacher M, De Bellis G, Rizzi E, Dumelin C, Melkko S, Neri D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17670–17675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805130105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Clark MA, Acharya RA, Arico-Muendel CC, Belyanskaya SL, Benjamin DR, Carlson NR, Centrella PA, Chiu CH, Creaser SP, Cuozzo JW, Davie CP, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:647–654. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Buller F, Steiner M, Scheuermann J, Mannocci L, Nissen I, Kohler M, Beisel C, Neri D. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:4188–4192. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Griffiths AD, Williams SC, Hartley O, Tomlinson IM, Waterhouse P, Crosby WL, Kontermann RE, Jones PT, Low NM, Allison TJ. The EMBO Journal. 1994;13:3245–3260. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Silacci M, Brack S, Schirru G, Marlind J, Ettorre A, Merlo A, Viti F, Neri D. Proteomics. 2005;5:2340–2350. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Weber M, Bujak E, Putelli A, Villa A, Matasci M, Gualandi L, Hemmerle T, Wulhfard S, Neri D. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Marks JD, Hoogenboom HR, Bonnert TP, McCafferty J, Griffiths AD, Winter G. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:581–597. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90498-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nissim A, Hoogenboom HR, Tomlinson IM, Flynn G, Midgley C, Lane D, Winter G. The EMBO Journal. 1994;13:692–698. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Hansen MH, Blakskjær P, Petersen LK, Hansen TH, Højfeldt JW, Gothelf KV, Hansen NJV. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1322–1327. doi: 10.1021/ja808558a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kleiner RE, Dumelin CE, Tiu GC, Sakurai K, Liu DR. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11779–11791. doi: 10.1021/ja104903x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Deng H, Zhou J, Sundersingh FS, Summerfield J, Somers D, Messer JA, Satz AL, Ancellin N, Arico-Muendel CC, Bedard KL, Beljean A, et al. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2015;6:919–924. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Litovchick A, Dumelin C, Habeshian S, Gikunju D, GuiÈ M, Centrella P, Zhang Y, Sigel E, Cuozzo J, Keefe A, Clark M. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10916. doi: 10.1038/srep10916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wichert M, Krall N, Decurtins W, Franzini RM, Pretto F, Schneider P, Neri D, Scheuermann J. Nat Chem. 2015;7:241–249. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Satz AL. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:2237–2245. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Melkko S, Mannocci L, Dumelin CE, Villa A, Sommavilla R, Zhang Y, Grutter MG, Keller N, Jermutus L, Jackson RH, Scheuermann J, Neri D. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:584–590. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Franzini RM, Ekblad T, Zhong N, Wichert M, Decurtins W, Nauer A, Zimmermann M, Samain F, Scheuermann J, Brown PJ, Hall J, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:3927–3931. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2015;127:3999–4003. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Krall N, Pretto F, Decurtins W, Bernardes GJL, Supuran CT, Neri D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:4231–4235. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2014;126:4315–4320. [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Skopic MK, Bugain O, Jung K, Onstein S, Brandherm S, Kalliokoski T, Brunschweiger A. MedChemComm. 2016;7:1957–1965. [Google Scholar]; b) Jetson RR, Krusemark CJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:9562–9566. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2016;128:9714–9718. [Google Scholar]; c) Krusemark CJ, Tilmans NP, Brown PO, Harbury PB. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Leimbacher M, Zhang Y, Mannocci L, Stravs M, Geppert T, Scheuermann J, Schneider G, Neri D. Chemistry. 2012;18:7729–7737. doi: 10.1002/chem.201200952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]