Abstract

This article aims at analysing the differences between European countries in the obstacles ex-offenders face due to having a criminal record. First, a comparative analytical framework is introduced that takes into account all the different elements that can lead to exclusion from the labour market by the dissemination of criminal record information. This model brings together social norms (macro level), social actors (meso level) and individual choices (micro level) in the same framework. Secondly, this model is used to compare the different impact of having a criminal record in Spain and the Netherlands. This comparison highlights three important findings: (1) the difference between norms of transparency/privacy and inclusive/exclusive ideals, (2) the significant role of social control agents, such as probation agencies and the ex-offenders’ social network, in shaping the opportunities that they have, and (3) self-exclusion seems to be a key mechanism for understanding unsuccessful re-entry into the labour market.

Keywords: Comparative framework, criminal background check, criminal records, re-entry into the labour market, stigma

Introduction

In 2010 Badr, age 32, worked as a social worker with problem youth in the Netherlands. His motivation to do this work was crystal clear: he was once a problem child himself. Fifteen years previously, when he was about 16 years old, he had committed several serious crimes, among which were violence, burglary, threatening behaviour and sexual assaults against girls. His punishment had been severe: 18 months’ imprisonment and two more years of treatment in a closed institution. This treatment was considered to have been successful: Badr learned from his mistakes. There is, according to his psychiatrist, no risk of reoffending. During his work, Badr completed a follow-up study on social work and received the opportunity to advance his career through promotion. However, in order to get to this position, he was required to have a ‘clean’ criminal record. This is not the case, even though the offences were committed when he was only a minor. His employer, now aware of his having a criminal record, fired him. Consequently, his diploma in social work was rendered useless. Now he, his wife and two young daughters can no longer make ends meet financially.

The impact of having a criminal record on the labour market is not the same in all European countries (Boone, 2011; Herzog-Evans, 2011; Larrauri, 2011; Morgenstern, 2011). Badr would have faced either more or fewer obstacles if he had been living in another European country. For instance, in Spain or France, Badr would not have had any problem working as a social worker at that age, as he was convicted as a minor and his criminal record would have been expunged by now (Carr et al., 2015).1 Yet, in the UK – as in the Netherlands – this would create serious obstacles for some types of employment because sexual offences would not become spent or expunged (Maruna, 2001; Thomas, 2007).

This article draws a framework for an analysis and comparison of how criminal records affect ex-offenders’ lives, in particular their re-entry into the labour market, in different European countries. We explore the case of Spain and the Netherlands. The theoretical framework is illustrated with preliminary empirical findings from two separate research studies carried out in the course of our PhD projects. The examples, such as the case of Badr mentioned above, derive from in-depth interviews with young adult ex-offenders, aged between 17 and 32 (37 in Spain and 38 in the Netherlands), and with probation officers.2

Up to now there has been a lack of comparative empirical research on the impact of having a criminal record on the labour market (Boone, 2012; Larrauri, 2014; Jacobs, 2015). Previous research focused on differences in national legislation, policies and decision-making practices (Damaska, 1968; Loucks et al., 1998; Commission of the European Communities, 2005; Stefanou and Xanthaki, 2005, 2008; KPMG, 2009). However, for a full comparative picture, the differences in ex-offenders’ real lives should be taken into account. Also attention should be paid to the (changing) local and international, historical and cultural contexts that shape the use of criminal background information in a specific society.

Spain and the Netherlands are two good candidates to start a comprehensive comparison. Formally, they reveal a contrast in regulating the dissemination of knowledge concerning criminal records. In Spain, employers cannot have direct access to another person’s criminal record, yet they have the possibility to ask employees to submit an extract of their criminal record (Larrauri and Jacobs, 2013). In the Netherlands, in contrast, no one can obtain an extract of someone’s criminal record for pre-employment screening. A special administrative agency at the Ministry of Security and Justice issues Certificates of Conduct for employment purposes. This is a document in which the State Secretary for Security and Justice declares that the applicant has not committed any criminal offences that are relevant to the performance of his or her duties. Once issued, the Certificate of Conduct does not reveal any criminal record information (Boone, 2011). So, taking into account the more protective system in the Netherlands when examining obstacles to re-entry into the labour market, we expect that ex-offenders in this country will face fewer obstacles than those in Spain. In the Netherlands, employers cannot obtain extracts from criminal records, whereas in Spain they can ask employees to provide such extracts.

The article is divided into two sections. To begin with, a comprehensive comparative framework is created to sort out the different elements that affect ex-offenders’ daily lives and influence their re-entry process. This holistic approach takes into account culture, norms, institutions, agents and individuals’ experiences altogether. The aim of the model is to weigh these different aspects and point out which factors are relevant for its outcome. The second part is a first attempt to use this model to describe the different impact of having a criminal record in Spain and the Netherlands.

A comparative model

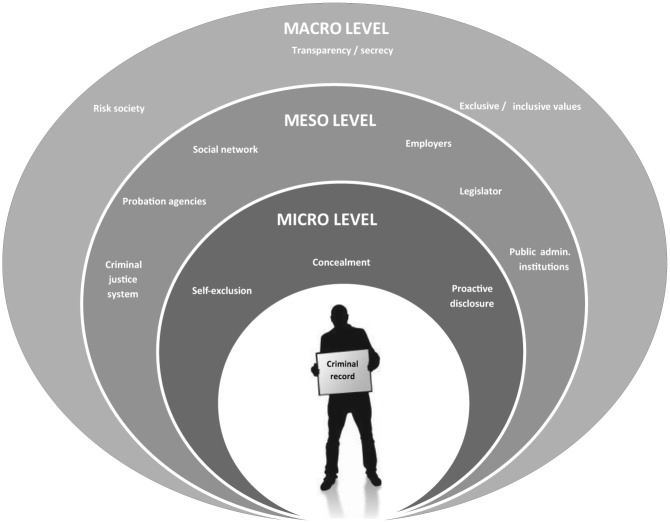

The systematic comparative framework is divided into three levels (Figure 1). The macro level refers to the construction of norms – either formal by law or informal by tradition or customs – that govern social behaviour. Previous literature has mainly focused on this level. The meso level focuses on social institutions and agents that shape the opportunities individuals with a criminal record have in the labour market. The micro level addresses the individual’s behaviour regarding searching and finding employment. These levels appeared to be helpful in carrying out qualitative comparative research on individuals with a criminal conviction history in Spain and the Netherlands.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms explaining the impact of criminal records on re-entry into the labour market.

The model allows consideration to be given to the profound interrelations between several aspects at the same time. For instance, norms at the macro level form the basis for social interaction, which guides the behaviour of the different actors at the meso and micro levels and, consequentially, interferes with individuals’ options in their re-entry process. The way individuals consequently deal with the ‘label’ of having a criminal record is then analysed at the micro level.

Macro level

The macro level encompasses three main dimensions. These refer to state powers and structural, social and cultural forces in wider society that shape public policies regarding criminal background screenings.

Risk society

Thomas (2007), Jacobs (2006), McAlinden (2012), Thomas and Hebenton (2013) and Backman (2012) mention that the ‘culture of control’ (Garland, 2001) has facilitated criminal background checks in the labour market. The more risk averse a society is, the more preventive measures employers take towards job applicants and employees, so the screening of criminal backgrounds increases. Similarly, Larrauri (2014) argues that the increase in criminal record checks can be understood in light of transferring the management of risk from the state to the community. Moreover, these risk-averse attitudes can lead to an increase in legal responsibilities. In the Netherlands, the legislator provides every employer with an (administrative law) instrument to avoid such liability, which is, increasingly, part of security policies. The role of the media also seems to be fundamental in a risk-oriented society (Snacken, 2010). When the media report extensively on criminal cases, the culture of control increases and ex-offenders will experience more obstacles to reintegrating into society (McAlinden, 2012).

Inclusive vs. exclusive values

The structure and values of societies in relation to crime and punishment are compared by Snacken (2010). An important finding is that, in Nordic countries, more inclusive values led to soft regimes, maintaining lower prison rates, whereas in the English-speaking countries, more exclusive values led to strict regimes and higher prison rates (Pratt and Eriksson, 2014). Previously, Young (1999) had used the inclusion/exclusion division to explain temporal variations in the crime control system in the UK, which he concludes to be a ‘bulimic society’ that includes and excludes deviants at the same time. One of the striking examples of this systematic ambivalence that he provides is the use of criminal records in the labour market. McAlinden (2012) and Petrunik and Deutschmann (2008) too have introduced the dimension of inclusion/exclusion to understand differences between countries in the use of vetting schemes for sexual offenders. Following this reasoning, criminal background screenings in the labour market could be clearly considered as an exclusionary measure or a proxy for an exclusive society (Díez-Ripollés, 2013).

Privacy vs. secrecy

Scholars agree that stigmatization processes need to be limited after offenders have completed their sentence, in order to achieve successful re-entry into society (LeBel, 2012; Murphy et al., 2011). In general it is assumed that more respect for ex-offenders’ privacy rights leads to less stigmatizing effects resulting from their having a criminal record. Previous research on privacy/transparency focused on the differences between common and civil law countries. Herzog-Evans (2011) classifies countries such as England and Wales and Australia as regulating a ‘right to know’, which allows for public access to criminal records. On the other side, Continental European countries, such as France, Germany and Spain, are classified by Herzog-Evans as upholding a ‘right to be forgotten’. This means criminal record information is restrictively disclosed, for example only to administrative authorities. Herzog-Evans (2011: 2) perceives the Netherlands to be an exception to this classic dichotomy: it has ‘one foot in common law countries and one foot in continental Europe jurisdictions’.

Despite the differences between the United States and Europe regarding the concept of privacy (Whitman, 2004), some important developments from the US are also relevant in the European context. Jacobs (2006) argues that regulating privacy protection in the US, by restricting or prohibiting the dissemination of criminal background information, is likely to result in a black market. Many officials have access to this kind of information and can (even be bribed to) disclose it without permission. Purchasing information from unofficial sources was also one of the reasons the Dutch legislature established a central agency issuing Certificates of Conduct (Brok, 1999; Kralingen and Prins, 1996). Another characteristic of the US is the declining respect for privacy by the media combined with the characteristics of modern information and communication technologies, which ensure that data once published on the Internet is hardly ever removed from it. In this way, criminal history information can be made accessible without limitation and can never be removed entirely. Such developments are – as far as we are aware – not (yet) common in Spain or the Netherlands, where the government remains the main criminal records repository.

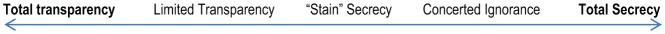

The protective function of the right to privacy is, however, only a legal protection against an infringement of this right. Therefore, we use the much broader concept of secrecy, meaning the absence of particular knowledge. This goes beyond the legal (privacy) structure of a society by incorporating the way it deals with values of inclusion and exclusion. We developed the transparency/secrecy model below in order to be able to capture both of these aspects in one single framework. Cohen’s (2000) work is used to describe five stages of the dissemination of knowledge along a line between total secrecy and total transparency:

In a stage of ‘total secrecy’, at the one extreme, no information is revealed to third parties for purposes other than the criminal procedure. This could be similar to the status of the criminal records of juvenile ex-offenders concerning non-sexual crimes in Spain. Such information is never included in criminal record certificates and there are no exceptions to this rule.

Figure 2.

Five stages of the dissemination of knowledge.

A stage of ‘total transparency’, at the other extreme, can be linked to the situation in the US, where court files and Internet information on criminal histories are (almost) freely accessible. Between these two poles, we can find three more stages.

‘Limited transparency’ indicates situations in which detailed information can be obtained by third parties with the consent of the person involved. In this way, Spanish employers can – indirectly – obtain limited knowledge of an applicant’s criminal convictions since reaching adulthood.

‘Stain secrecy’ refers to a situation in which information is provided only concerning the fact that there has been contact with the criminal justice system. Yet, information on the nature of the – alleged – criminal acts is not provided. For example, in the Netherlands no one will be issued with a copy of a criminal record extract outside the criminal procedure, in order to protect employees from coercion to provide such extracts to employers. Yet, when the requested Certificate of Conduct is not issued, the employer knows of the ‘stain’, ‘mark’ or ‘label’ that the ex-offender has, yet there is nothing more to know than (just) that. Although a ‘stain’ policy is more oriented towards secrecy, it in fact allows for knowledge dissemination in a way that might create ‘mysterious’ or ‘risky’ individuals (Siegel, 2012: 5). Because, Siegel (2011: 109) argues, next to protection against stigmatizing knowledge, ‘secrecy can also be dangerous, because … it can lead to misunderstandings about the activities and aims of the individuals involved and to negative stereotyping and speculation’.

‘Concerted ignorance’ refers to situations in which agents do not have an interest in asking what has been going on or the social environment benefits from the continuation of an existing situation, so no one will be inclined to ask difficult questions: ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell’ (Van de Bunt, 2010: 445). When information is kept secret as far as third parties are concerned, they can be protected against needless ‘guilty knowledge’ (Siegel, 2012: 4). For example, an employer might not want to know that his noticeably good employee has been convicted, otherwise he might be impelled to let this employee go or he might become (legally) responsible for any misbehaviour in the workplace.

Meso level

The meso level focuses on social institutions and agents that are responsible for defining the legal and social norms for the disclosure of criminal background information. Six main categories of social control agents are defined. In the public sector we find: the legislator that creates the law; the criminal justice system that fulfils the ambivalent task of supervision and control on the one side and guidance and assistance on the other; and the public (administrative) institutions, located outside the criminal justice system, that execute the regulations on criminal records. In the private sector it is important to consider: the institutions and non-governmental and commercial organizations that carry out functions of supervision and reintegration outside the criminal justice system; employers, the agents that provide employment opportunities, internships or voluntary work (although employers can also be public institutions); and the social network of the individual, also an important source of finding jobs.

In order to understand the behaviour of these social institutions and actors, two kinds of powers are described: responsibility and discrimination.

Responsibility

By referring to responsibility we can analyse actions on the thin line between protecting safety and advancing ex-offenders’ inclusion. It is often presumed that employers seek as much information as possible in their decision-making process, in order to guarantee a well-substantiated outcome. Jacobs (2006) argues that in the US the increase in criminal background checks is related to the negligent hiring doctrine. Although the legal principle of respecting privacy, as prevalent in the Netherlands, can protect ex-offenders, transparency can, at the same time, generate trust, because it can remove doubts and uncertainty and, thereby, create trust and inclusion (Boone et al., 2014). For example, in the Netherlands an employer might exclude an applicant in order to avoid any possible risk, based on knowing only that this person has had some problems with the criminal justice system, but having no more detailed information than this. However, if the employer had known the characteristics of the criminal offence, which, for instance, might be only petty crime not related to the job, he or she might not have chosen to exclude this ex-offender (Holzer et al., 2007).

Consequently, a national system that is not designed to provide for the disclosure of criminal records (‘stain’ secrecy) can create a context in which ex-offenders convicted of only minor crimes face more difficulties in finding a job. In this way, risky individuals can be created and the criminal record becomes a general ‘mark of marginality’, apart from aspects such as the severity, nature and relevance of previous convictions. For example, in the Netherlands young people are rejected for tertiary education, even though their former criminal acts do not appear to constitute a serious risk. In this way, their criminal past constitutes a mark of marginality that is considered a risk of not completing education and leads to exclusion. Moreover, when employers cannot obtain criminal background information as desired, they could ‘statistically’ discriminate against social groups known to have a relatively higher proportion of convicted individuals (Bushway, 2004).

Responsibility also plays a role for institutions within the criminal justice system and public or private reintegration organizations. Van de Bunt (2012: 54) considers probation professionals to be ‘hybrid’ as a result of conflicting interests, which are part of their supervising tasks of controlling and preventing risk, on the one hand, and helping to reintegrate on the other. Officers of the Dutch probation service recognize this ambivalent task. For example, in the case of a person, convicted of sexual offences and not able to find a job anywhere, hired to do some voluntary work at a holiday park, the probation officer struggled with the question of whether or not to inform the employer about his criminal past. This contradiction also follows from an interview with a parole officer in Spain:

We tried to do it [check that the individual is working] in a cautious way … Once, I talked with an employer to ask him to make a parolee come to the ‘Social Services of Penal Execution’ [the name of parole offices in Spain]. When he heard the word ‘penal’ I noticed that he became nervous… then I thought: ‘I don’t know if I should have mentioned the word “penal”.’

Discrimination

By referring to discrimination we can analyse the consequences of using criminal background information and assess its relevance. Previous research has pointed out that the predictive value of criminal records diminishes over time (for example, Bushway et al., 2011). Their relevance is furthermore determined by the seriousness of the offence, recidivism and its relationship to the specific occupation (Boone, 2011; Lam and Harcourt, 2003; Larrauri, 2014). Some authors argue that establishing the relevance of previous convictions is more favourable to ex-offenders if conducted by an external agency because employers might have prejudices against ex-offenders beyond the actual risk concerns (Apel and Sweeten, 2010). If the relevance test is carried out externally, for example by a public administrative agency, as takes place in the Netherlands, it is assumed to be more objective and less discriminatory towards ex-offenders.

In countries where most employment is found through relatives and acquaintances, the social network can be an important means of disseminating knowledge. Then the employer might not need an official file summarizing all previous convictions because there are other – informal – ways of knowing about the person’s criminal background. Interviews in Spain reveal the impact that the social network can have on job applications. A man wanted to work as a fishmonger because he had learned this business during a course in prison. The prison staff made it very clear to the students that, once they were outside the prison system, no one could know that the course had been followed in prison. Yet, during a job application process, the man was recognized – through the grapevine – as someone who had undertaken the course in prison. He felt embarrassed and ultimately did not get the job.

However, most interviewees from Spain mention that trust leads to less discrimination. This trust seems to be based on the knowledge an employer collects by assessing direct signs rather than on officially registered criminal background information. Cherney and Fitzgerald (2014) highlight that a common social network functions as a ‘certification’ of reliability and capability and evidence that the ex-offender has adopted a conforming role. The following quote from an ex-prisoner in Spain shows how the social network can redeem the individual and create job possibilities. He was asked whether he believes his acquaintances have stopped recommending him since he has been in prison:

No, I rather think they feel a bit sorry for me. I have lost the bar I had… I think they would recommend me, because they know where I came from and that I have to struggle to find my own stability.

From this interview it seems that the social network helps ex-prisoners to rebuild their social life by providing employment. Yet, there are also respondents in Spain who talk about being discriminated against by their social network. A respondent recalled that people are two-faced: ‘when you come out of prison, they say they are going to help you, but eventually they seem unwilling to provide a good reference.’

In Spain, supervising professionals also carry out a relevance test before deciding whether or not to communicate the supervised offender’s criminal history to an employer. For instance, the person responsible for the Job Notice Board for parolees in Catalonia mentioned that she does not disclose the specific details of a criminal background to employers. However, she herself assesses the suitability of the offender for the position in question. In the Netherlands, reintegration professionals often try to avoid discrimination due to official administrative background screening by negotiating directly with employers who seem willing to contribute to ex-offenders’ reintegration.

Micro level

The micro – or individual – level focuses on the options that individuals have and choose to deal with criminal records. The individual aspects that determine ex-offenders’ position in society are multiple. Demographic characteristics as well as multiple social and psychological factors (character, motivation, cognition and agency) can play a role here. Cultural values, previous socialization and peer groups can also influence the way in which individuals deal with (possible) stigmatization. Next to these individual characteristics, the reintegration process can be full of – external – obstacles and encouragements. Therefore, it is important to examine the ex-offender’s experiences that either increase or decrease his or her motivation, self-esteem and self-efficacy during the reintegration process. Next, it should be examined to what extent disappointments and successes can be related – alongside individual characteristics – to societal reactions, deriving from the context of the macro and meso levels.

Confronted with the different opportunities ex-offenders have in society, the response they choose will affect their position in society (Goffman, 1990; Harding, 2003). Previous literature on stigma has operationalized these choices as different strategies (Lebel, 2008). In the US, Harding (2003) found that the way in which ex-offenders manage their stigma has an impact on their chances of finding employment but also on their applying for it. Ex-offenders who conceal their former identity may sacrifice long-term employment and growth in earnings for short-term survival on the job market, whereas those who reveal their former identity may sacrifice finding employment in the short term for the sake of a long-term occupation.

Self-exclusion

When ex-offenders foresee that criminal records will be asked for, they can withdraw from the job-seeking process. This micro-level strategy of self-exclusion can explain the negative impact of having a criminal record. Forecasting a possible rejection, the ex-offender can decide either not to apply for a certain job or to exclude him/herself from the labour market completely. In the following quote, an ex-offender from Spain recalls holding back from applying for a training course run by the National Career Service, because he was afraid to show a qualification from a previous training course undertaken in prison. His quote exemplifies the frustration this withdrawal strategy causes:

I went to the INEM [the National Jobcentre] and I applied. I wanted to go on the cooking course. But, how can I go to INEM with that [the training course certificate obtained in prison]? I got a bit angry and I said to them to go to hell, so clear … It was not just one thing [that he had been in prison], but three [marks] … Doing that, they [the organizers of the course] make me feel frustrated.

Different research has highlighted the negative consequences of this mechanism. However, there is no extensive literature dealing with the notion of self-exclusion in this field. Murphy et al. (2011) speak of an ‘upward bias’ if ex-offenders exclude themselves a priori from jobs for which (they believe) their criminal history will be checked. They also call this the ‘social emasculation’ of ex-offenders since they believe that they are incapable of changing their circumstances. An example from an interview in the Netherlands shows how the strategy of self-exclusion works:

I had this issue with my manager about the Certificate of Conduct. He said: ‘If you haven’t done anything really bad, you’ll get it.’ I thought: Wow, do you really mean that? Because I knew I had already received a letter stating that I would not get my Certificate of Conduct… That was all. The way he said it to me was very offensive. … I was very ashamed. … I continued to work there for a few weeks, then I left.

Ex-offenders can face other forms of stigma, in addition to being an ‘ex-con’, on which they base their decisions regarding job applications (LeBel, 2008). In the Netherlands, for example, Moroccan youngsters feel doubly stigmatized: they perceive that they are being discriminated against because of their ethnic background alongside a criminal stigma. It can be said that the race stigma doubles the criminal one (LeBel, 2012). It can therefore be expected that ex-offenders from a marginalized social background in general tend to withdraw from job entry processes because they accumulate stigmas.

Concealment

Regarding avoidance or concealment strategies, research in the UK (Metcalf et al., 2001), the US (Harding, 2003) and Hong Kong (Chui and Cheng, 2013) shows that people with criminal records, when they think they are not going to be asked about their criminal record, opt for a strategy of keeping quiet. They either avoid mentioning their criminal record during a job application process or cover it up with some excuses. The following quote from Spain illustrates the willingness and reason to use a strategy of avoidance during a job interview. The respondent has never actually faced these kinds of questions, so his answer is based on a ‘perceived’ instead of an ‘enacted’ stigma (LeBel, 2012). He was asked whether he would mention that he is on parole during a job interview:

No. If there is a lot of trust, yes, but I am not going to say this and be fired in two days… It’s logical. The man who hires a prisoner, he doesn’t know if he will steal, if he will commit a crime, if he will kill. For this reason, they are not going to pick you directly.

This example shows that in Spain ex-offenders are likely not to mention their criminal past unless there is a lot of trust involved. Yet concealment strategies have been related to feelings of stress because ex-offenders have to deal with hiding a part of their past (Lebel, 2008). Not telling the whole truth to employers can make ex-offenders feel apprehensive, which can create problems in answering questions promptly or properly during an interview, subsequently leading to failing the job interview. However, covering strategies are likely to be related to lesser amounts of stress during an interview if recruiters cannot easily find out about criminal records because this information is considered to be confidential and is not easily accessible to them.

Proactive disclosure

If ex-offenders anticipate that employers will eventually find out about their criminal past or if they think that this past is not relevant, they can opt for proactive disclosure. Research on other kinds of stigmas indicates that proactive strategies are beneficial in the lives of the stigmatized (Lebel, 2008). Trust seems to be fundamental in opting for this strategy. One of the Spanish respondents answered, when asked whether he would be open about his previous convictions: ‘Well, if there is trust, I would mention it, but in principle, no.’ The following quote shows what can also happen after a Spanish interviewee explains his criminal past to an employer who asks about his previous lack of work experience and the gap in his CV:

It is huge. If they do ask, then yes, I tell them a bit. But if they do not ask, I never tell …. If I tell them, their faces change. … they become very surprised… but I don’t know the reaction… I see them being surprised, but not very negative… They just stop asking questions…

Differences between the Netherlands and Spain

Macro level

At the macro level we analysed the social, cultural and structural norms regarding risk and inclusion/exclusion, and the structures for disseminating criminal record information. In the course of our PhD research we found some hints that attitudes concerning risk aversion are more prevalent in the Netherlands than in Spain. A Dutch civil servant referred to this as the ‘risk-rule reflex’: when a particular risk (an offence) becomes reality, the reflex action of politicians is often to create more preventive measures, trying to meet the public claim for more control and reducing risk. This was the case when a high school teacher was caught chatting about sex with a student via social media. The Dutch Minister of Justice consequently demanded restrictions on the issuing of Certificates of Conduct. In this case, however, it was not a problem of a certificate being issued too easily; the problem was that the school did not demand a certificate at all. Therefore, tightening the rules seems to be a measure only to satisfy the demands of the media and the general public for more safety measures instead of an accurate strategy to prevent such incidents reoccurring. In Spain, media attention on such issues is very different. For instance, an employment termination case involving a person who had been hired as a supervisor in a juvenile detention centre, when he had previously been convicted of abusing children under his supervision and of possessing child pornography, resulted in only a brief mention in newspapers and on TV.

Regarding inclusive/exclusive values there seems to be a slightly more exclusive system in the Netherlands. Both Spain and the Netherlands legally prescribe which types of jobs require criminal record checks, such as the judiciary, politicians, police officers, public servants, medical staff, private security guards and taxi drivers. In the Netherlands, teachers and caregivers of children are also legally obliged to submit a Certificate of Conduct. In Spain, this provision has only recently been introduced.3 Expungement procedures, however, do not greatly differ. In the Netherlands, the general ‘expiry’ period – after which an offender (unless convicted of homicide or sexual offences) is eligible to receive a Certificate of Conduct – is four years. In Spain, a conviction becomes spent after a predetermined period, which varies from six months for minor violations to 10 years for serious offences. For short prison sentences – below three years – this period is three years.

Regarding the transparency/privacy dimension, the Netherlands has a more protective system towards ex-offenders than Spain. The Dutch system is designed to prevent criminal background information being revealed to third parties. Yet, in the Netherlands, no exception is made for the disclosure of the criminal records of minors, in contrast to Spain. The administrative agency just applies a shorter expiry period for the criminal records of minors. In the Netherlands, moreover, out-of-court settlements or merely being a suspect also generally lead to the refusal of a Certificate. The situation in the Netherlands exemplifies a system favouring privacy towards ex-offenders, while at the same time providing limited knowledge on people with a ‘stain’, without providing any information on what that blemish or label implies, that is, what the nature of their criminal background is. For example, it is difficult for an ex-offender to receive a Certificate of Conduct to work at the Port of Rotterdam or at Schiphol Airport, due to very strict safety policies in these areas. Even the most minor offences can lead to a rejection, even when there is no actual risk of reoffending or reoffending would not be detrimental to the occupation in question. Nevertheless, the applicant can be considered to be a ‘risky individual’ and not allowed to work in such a high-risk position.

Meso level

At the meso level we study the responsibility of and discrimination by social institutions and actors. In practice, employment discrimination seems much higher in the Netherlands than in Spain. In 2015, more than 860,000 Certificates of Conduct were requested, which seems a lot compared with the number of people who had paid work: 8.3 million.4 The majority of the interviewed Dutch ex-offenders who were actively looking for employment had experienced concrete problems due to their criminal past. Almost all ex-offenders seem to worry about the potential consequences of having a criminal record. When asked about this, a respondent replied: ‘You ask me this for the sake of asking. Of course everybody knows having a criminal record makes finding a job more difficult.’ Men experience most difficulties in the field of taxi driving, security and youth work. Women in particular face difficulties receiving a Certificate of Conduct for cleaning work and caring occupations, for example with children or the elderly. In contrast to the Netherlands, in Spain most of the ex-offenders interviewed were even surprised that research was being carried out on this issue. An adult ex-offender, who had been in prison for a burglary, replied – when asked about the effect of having a criminal record – ‘No, this no. … It does not affect you because it does not appear. So, you do not have to mention it anywhere. Then, it is only known by you.’ Out of 37 Spanish interviewees, only 2 had been asked to reveal their criminal record during a job interview.

However, previous convictions do affect the real lives of the Spanish interviewees because the majority of them found work through acquaintances. Then their criminal past was already known to the employer. Here, as aforementioned, trust in the convicted person prevents discriminatory attitudes. Additionally, this practice might explain why there are not as many legal requirements to carry out criminal record checks as there are in the Netherlands. If informal ways of recruiting (through family and friends) are the most common, requiring employers to carry out criminal background screenings might hinder selection processes in Spain.

Regarding responsibility, in the Netherlands the law – out of respect for privacy rights – strictly prescribes in what ways criminal background information is allowed to be disseminated. The Spanish system, in contrast, leaves actors at the meso level, such as employers, considerable leeway for a case-by-case assessment of an applicant’s criminal past. This, however, seems to lead to more inclusive attitudes on several occasions. For example, parole and probation officers perform – covert – employment screenings themselves, so that employers do not have to make these decisions – which is deemed to influence ex-offenders’ chances in the labour market negatively. The exclusive attitudes in the Netherlands can be related to possible negligent hiring issues, since administrative screening – resulting in either the issuance or the refusal of a Certificate of Conduct – is widely acknowledged and promoted. Yet, according to the literature, negligent hiring cases seem to be uncommon in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, since Dutch law provides for the option to have all employees screened, such claims have the potential to be successful at any rate. In Spain, we found only one case in recent years that could be related to negligent hiring.5

Micro level

At the micro level we deal with the choices of individuals with a criminal conviction history when dealing with stigma in the labour market. In Spain, concealment is the most prevalent strategy, probably owing to the fact that, although criminal record extracts can be straightforwardly requested, this does not often happen in practice. When the job is found through the ex-offender’s social network and there is a relationship of trust with the potential employer, ex-offenders opt for the (proactive) disclosure of their former indiscretions, although without providing the most negative details. Still, withdrawal strategies are used in both countries – in Spain if ex-offenders foresee that their potential employer will get to know about their criminal past through others, in the Netherlands if ex-offenders expect that they will have to provide a Certificate of Conduct. As requests for the Certificate have increased five-fold in the past decade and keep rising every year, self-exclusion, based on an expected negative outcome, is likely to increase as well. The choice to withdraw from the labour market can even be reinforced by risk-averse attitudes emerging from the public, the media and politics at the macro level. Such exclusive attitudes seem to be more prevalent in the Netherlands and can reinforce both formal and informal obstacles for ex-offenders in the labour market.

Conclusion

The title of this article refers to criminal records as ‘hidden’ obstacles. Previous comparative research on their impact in ex-offenders’ lives mainly focused on differences in legal and administrative terms. Yet, when the law is studied not only in books but also in practice, a totally different picture emerges. In this article, a comparative model is put forward to take comprehensively into account all the different elements that operate within the social context (such as politics, public opinion, the media and actions by social control agents), which can – eventually – lead to discrimination and (self-)exclusion from the labour market. Basically, this model brings together within the same framework social norms at the macro level, social actors at the meso level and individual strategies and choices at the micro level.

To study the impact of having a criminal record, the perceptions of individuals should be taken into account, but their attitudes are – at the same time – shaped by the messages they receive from their social context. Choices made at the macro and meso levels thus influence the strategies that ex-offenders follow to find employment, and are therefore fundamental to understanding the failure or success of their re-entry into the labour market. Further research on the role, attitudes and choices of employers in particular could be of much added value. Moreover, all factors at the three different levels and their relative effects need to be ‘weighted’. In addition, methodological issues need to be considered in a future article, allowing us to compare the results of our qualitative research studies in a methodologically rigorous way. We hope the current article contributes to creating public policies adapted to specific national contexts, which avoid unforeseen and counterproductive collateral consequences of criminal records in the labour market.

The comparison between the Netherlands and Spain has ‘uncovered’ three important elements that operate at these different levels. At a macro level, our first results seem to indicate that attitudes in a society towards risk and exclusiveness/inclusiveness are much more significant than the more ‘visible’ and mere legal ones of transparency/privacy. Previous research frequently emphasized privacy dimensions; however, comparing Spain with the Netherlands helps to illustrate that these dimensions operate in another way and have a different impact. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, the number of applications for a Certificate of Conduct in the Netherlands is much higher than the number of requests for criminal record extracts in Spain, even though the Netherlands seems to uphold higher privacy standards that limit direct access to criminal conviction information. At a meso level, the impact of the stigma of having a criminal record depends not only on the provisions established by law but also on choices regarding responsibility, relevance and discrimination by agents who are fundamental in the process of re-entry, such as the social network and probation/reintegration agencies. At the micro level, self-exclusion seems to be a crucial yet mostly under-recognized mechanism that is important to explain unsuccessful re-entry into the labour market. All these elements are fundamental for our understanding of the differences between countries in the obstacles that ex-offenders face due to their having a criminal record.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Miranda Boone, Elena Larrauri, Dina Siegel and the members of the criminology research group of the Willem Pompe Institute of Utrecht University for their useful comments on earlier versions of this article.

This situation is currently changing in Spain.

Informed and voluntary consent was obtained for all interviews and different measures were taken to avoid participants being harmed. There has also been a strong concern to ensure confidentiality in all processes in both pieces of research. Further information on this research can be provided upon request.

Real Decreto 1110/2015, de 11 de diciembre, por el que se regula el Registro Central de Delincuentes Sexuales.

Sentencia núm. 802/2012 de 9 de noviembre de la Audiencia Provincial de Valencia, Sección 3ª.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Marti Rovira’s research has been funded through the projects ‘Offender Supervision in Europe’ supported by COST (Grant IS1106), ‘La regulación de los antecedentes penales: efecto en el acceso al Mercado laboral de los jóvenes’ supported by the Research Grants RecerCaixa (Grant RecerCaixa 2013), ‘Penologia europea: La seva influència en el sistema de penes espanyol’ supported by AGAUR (Grant DURSI-AGAUR SGR2014 426) and ‘Ejecución y supervisión de la pena: Calidad de la intervención, legitimidad y reincidencia’ supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and FEDER, EU (Grant DER2015-64403-P). Elina Kurtovic’s research is funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), project number 406-12-040.

Contributor Information

Elina Kurtovic, Utrecht University, The Netherlands.

Marti Rovira, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Spain.

References

- Apel R, Sweeten G. (2010) The impact of incarceration on employment during the transition to adulthood. Social Problems 57(3): 448–479. [Google Scholar]

- Backman C. (2012) Criminal Records in Sweden: Regulation of Access to Criminal Records and the Use of Criminal Background Checks by Employers. PhD thesis, University of Gotebörg, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Boone M. (2011) Judicial rehabilitation in the Netherlands: Balancing between safety and privacy. European Journal of Probation 3(1): 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Boone M. (2012) Criminal records as an instrument of incapacitation. In: Malsch M, Duker M. (eds) Incapacitation. Trends and New Perspectives. Surrey: Ashgate, 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Boone M, Van de, Bunt H, Siegel D. (2014) Gevangene van het verleden. Apeldoorn: Politie en Wetenschap; Utrecht University, Rotterdam: Erasmus University. [Google Scholar]

- Brok H. (1999) Gevangen in Het Verleden. Utrecht: Wetenschapswinkel Rechten. [Google Scholar]

- Bushway SD. (2004) Labor market effects of permitting employer access to criminal history records. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 20(3): 276–291. [Google Scholar]

- Bushway SD, Nieuwbeerta P, Blokland A. (2011) The predictive value of criminal background checks: Do age and criminal history affect time to redemption? Criminology, 49(1): 27–60. [Google Scholar]

- Carr N, Dwyer C, Larrauri E. (2015) Young people, criminal records and employment barriers. In: NIACRO and The Bytes Project (Report) New Directions: Understanding and Improving Employment Pathways in Youth Justice in Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland: Department of Employment and Learning, 7–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cherney A, Fitzgerald R. (2014) Finding and keeping a job: The value and meaning of employment for parolees. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. Epub ahead of print 1 September 2014. DOI: 10.1177/0306624X14548858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui WH, Cheng KK. (2013) The mark of an ex-prisoner: Perceived discrimination and self-stigma of young men after prison in Hong Kong. Deviant Behavior 34(8): 671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (2000) States of Denial: Knowing about Atrocities and Suffering. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities (2005) Annex to the WHITE PAPER on exchanges of information on convictions and the effect of such convictions in the European Union. Commission Staff Working Paper. Report SEC(2005) 63, Brussels, 25 January URL (accessed 5 October 2016): http://db.eurocrim.org/db/en/doc/592.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Damaska MR. (1968) Adverse legal consequences of conviction and their removal: A comparative study. Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science 59(3): 347–360. [Google Scholar]

- Díez-Ripollés JL. (2013) Social inclusion and comparative criminal justice policy. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention 14(1): 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Garland D. (2001) The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. (1990) Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. UK: Penguin Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Harding DJ. (2003) Jean Valjean’s dilemma: The management of ex-convict identity in the search for employment. Deviant Behavior 24(6): 571–595. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog-Evans M. (2011) Editorial: ‘Judicial rehabilitation’ in six countries: Australia, England and Wales, France, Germany, The Netherlands and Spain. European Journal of Probation 3(1): 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer HJ, Raphael S, Stoll MA. (2007) The effect of an applicant’s criminal history on employer hiring decisions and screening practices: Evidence from Los Angeles. In: Bushway SD, Stoll MA, Weiman DF. (eds) Barriers to Reentry? The Labor Market for Released Prisoners in Post-Industrial America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 117–150. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JB. (2006) Mass incarceration and the proliferation of criminal records. University of St. Thomas Law Journal 3(3): 387–420. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JB. (2015) The Eternal Criminal Record. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kralingen RW, Prins JEJ. (1996) Waar een wil is, is een weg? The Hague: SDU Uitgevers. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG (2009) Disclosure of Criminal Records in Overseas Jurisdictions. Report for the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI), March London: CPNI; URL (accessed 5 October 2016): https://www.cpni.gov.uk/documents/publications/2009/2009-criminal_records_disclosure_countriesr-u_march09.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lam H, Harcourt M. (2003) The use of criminal record in employment decisions: The rights of ex-offenders, employers and the public. Journal of Business Ethics 47(3): 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- Larrauri E. (2011) Conviction records in Spain: Obstacles to reintegration of offenders? European Journal of Probation 3(1): 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Larrauri E. (2014) Legal protections against criminal background checks in Europe. Punishment and Society 16(1): 50–73. [Google Scholar]

- Larrauri E, Jacobs JB. (2013) A Spanish window on European law and policy on employment discrimination based on criminal record. In: Daems T, Snacken S, van Zyl Smit D. (eds) European Penology? Oxford: Hart, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- LeBel TP. (2008) Perceptions of and responses to stigma. Sociology Compass 2(2): 409–432. [Google Scholar]

- LeBel TP. (2012) Invisible stripes? Formerly incarcerated persons’ perceptions of stigma. Deviant Behavior 33(2): 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Loucks N, Lyner O, Sullivan T. (1998) The employment of people with criminal records in the European Union. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 6(2): 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- McAlinden AM. (2012) The governance of sexual offending across Europe: Penal policies, political economies and the institutionalization of risk. Punishment and Society 14(2): 166–192. [Google Scholar]

- Maruna S. (2001) Making Good : How Ex-convicts Reform and Rebuild Their Lives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf H, Anderson T, Rolfe H. (2001) Barriers to Employment for Offenders and Ex-offenders. Part One. Research Report for the Department of Work and Pensions UK. Research Report No. 155, January London: Corporate Document Services. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern C. (2011) Judicial rehabilitation in Germany – The use of criminal records and the removal of recorded convictions. European Journal of Probation 3(1): 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy D, Fuleihan B, Richards S, Jones R. (2011). The electronic ‘scarlet letter’: Criminal backgrounding and a perpetual spoiled identity. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 50(3): 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Petrunik M, Deutschmann L. (2008) The exclusion–inclusion spectrum in state and community response to sex offenders in Anglo-American and European jurisdictions. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 52(5): 499–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt J, Eriksson A. (2014) Contrasts in Punishment: An Explanation of Anglophone Excess and Nordic Exceptionalism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D. (2011) Secrecy, betrayal and crime. Utrecht Law Review 7(3): 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel D. (2012) De sociale rol van het geheim: Inleiding. Tijdschrift over Cultuur and Criminaliteit 2(2): 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Snacken S. (2010) Resisting punitiveness in Europe? Theoretical Criminology 14(3): 273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanou C, Xanthaki H. (2005) Financial Crime in the EU. Criminal Records as Effective Tools or Missed Opportunities. The Hague: Kluwer Law International. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanou C, Xanthaki H. (2008) Towards a European Criminal Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T. (2007) Criminal Records: A Database for the Criminal Justice System and Beyond. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Hebenton B. (2013) Dilemmas and consequences of prior criminal record: A criminological perspective from England and Wales. Criminal Justice Studies 26(2): 228–242. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Bunt H. (2010) Walls of secrecy and silence: The Madoff case and cartels in the construction industry. Criminology and Public Policy 9(3): 435–453. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Bunt H. (2012) Stilzwijgen onder toezichthouders. Tijdschrift over Cultuur and Criminaliteit 2(2): 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Whitman JQ. (2004) The two Western cultures of privacy: Dignity versus liberty. Yale Law Journal 113(6): 1151–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Young J. (1999) The Exclusive Society: Social Exclusion, Crime and Difference in Late Modernity. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]