Abstract

Group A streptococcus (GAS) causes severe infections in obstetric patients. A rare complication is rapidly progressive necrotising myometritis. Postpartum necrotising myometritis has been previously described; however, antenatal development of such a condition is extremely rare. We present a patient who developed antenatal necrotising myometritis and toxic shock syndrome (TSS) due to GAS during the first trimester of pregnancy, eventually requiring hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy. We discuss the rare complication of ante-partum necrotising myometritis, as well as the antibiotic therapy, and treatment of TSS associated with severe Group A Streptococcal infections.

Keywords: Necrosing myometritis, toxic shock, Group A streptococcus, immunoglobulin, obstetric sepsis

Case report

A 28-year-old pregnant female (gravida 1, para 0) presented to a district hospital with a 24-hour history of lower abdominal pain, fever, and per vaginal bleeding. One week prior, she had been treated by her general practitioner for tonsillitis with a seven-day course of ampicillin, which she took for three days. Her last menstrual period had been eight weeks before, and two days prior to presentation ultrasound had demonstrated a viable foetus. She had no significant past medical history.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were as follows; temperature 39℃; heart rate 140 beats/min; blood pressure 103/40 mmHg; respiratory rate 20 breaths/min. She was alert and oriented. She had cool and mottled extremities but otherwise general examination was unremarkable. Per-vaginal examination revealed labial and vaginal swelling without discharge. Laboratory testing revealed; urea 6.8 mmol/L, creatinine 128 µmol/L, white cell count of 35 × 109/L, international normalised ratio (INR) 3.2, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 110 s, fibrinogen 1.3 g/L, platelet count 60 × 109/L, D-dimer 2.0 mg/L suggesting sepsis, acute kidney injury and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Urgent pelvic ultrasound revealed a non-viable foetus. In view of these findings, a diagnosis of infected products of conception was made. Antibiotic therapy with meropenem, ciprofloxacin and benzylpenicillin was commenced; her coagulopathy was corrected with fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and cryoprecipitate prior to undergoing an emergency dilatation and curettage procedure for evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPC). At surgery it was noted that whilst there was significant desquamation and swelling of the vagina and the cervix, the products of conception did not appear infected. The choice of antibiotics was predominantly to cover the possibility of streptococcal and clostridial infection.

After surgical intervention, she continued to deteriorate, developing worsening DIC, shock requiring catecholamine support and high ventilatory requirements. She was ventilated with synchronised intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) with tidal volumes of 6 mL/kg (450 mL), positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 8 cm H2O. She received continuous veno-venous haemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) from day 1 and continued to receive this until day 5, after which she started receiving intermittent haemodialysis. She was resuscitated with balanced electrolyte solution and blood products. The fluid resuscitation was guided by repeated bedside echocardiography. On the first day, she had a positive fluid balance of 6.5 L and this was carefully managed with a neutral fluid balance for days 2 and 3, eventually reaching targets of negative fluid balance from day 4 onwards. She was started on noradrenaline on day 1, and by day 2 her noradrenaline requirement reached a maximum of 22 mcg/min. She required ongoing support for her coagulopathy with transfusions of blood products and she was transfused platelets, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate on a nearly daily basis for the first three days. Twenty-four hours after admission, the initial cervical swabs grew Group A streptococcus (GAS); however, the blood cultures remained negative. She was treated for severe GAS infection with toxic shock syndrome (TSS). Benzylpenicillin and ciprofloxacin were continued and the meropenem was changed to clindamycin. She was also commenced on intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). The source of the GAS was still unclear and she underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen which revealed a bulky and heterogeneous uterus with generalised enhancement, along with fluid and gas in her endometrial cavity and Fallopian tubes. Although these findings were concerning, her clinical condition improved over the next 24 hours, and further surgical intervention was deferred.

On day 3, she developed a new fever with a rise in her white cell count from 16 × 109/L to 23 × 109/L. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis was performed to identify the extent of inflammation. It revealed enhancement of the uterus suggesting an inflammatory or infective process, along with a complex fluid collection in the endometrial cavity without enhancement. Based on the signs of worsening sepsis and the MRI findings, she underwent a laparotomy which revealed infarction and necrosis of the uterus, ovaries and Fallopian tubes, with extensive inflammation of the surrounding tissues (Figures 1 and 2). Total hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy were performed and subsequently there was a significant improvement in her clinical condition with complete resolution of shock and DIC on day 4. Her trachea was extubated on day 6 of her ICU admission, and she was transferred to the ward on day 7. She required haemodialysis for a further two weeks, and was discharged home on day 20. The final diagnosis was Group A streptococcal necrotising myometritis with TSS with confirmation of extensive haemorrhagic necrosis on histopathology (Figures 1–3).

Figure 1.

Extensive haemorhagic necrosis of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus and cervix.

Figure 2.

Extensive haemorrhagic necrosis of the uterine wall.

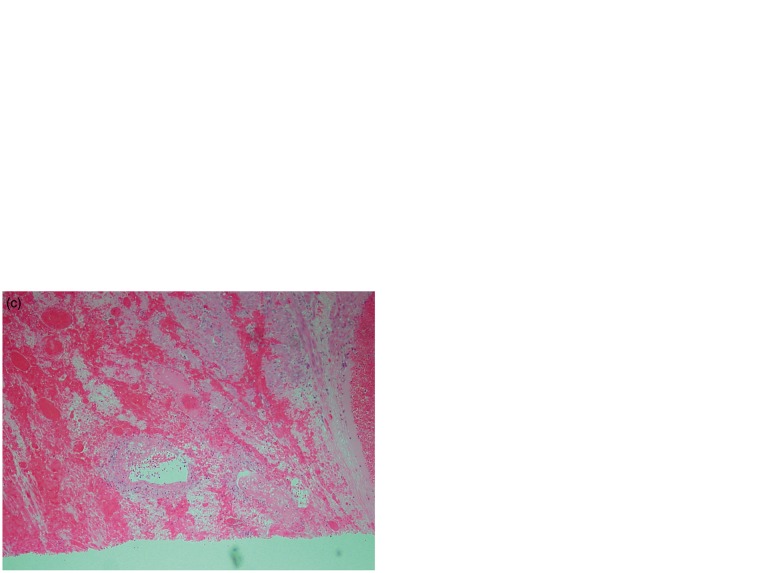

Figure 3.

(a–d) Pathological specimens of the necrotic tissue showing the microscopic and microvascular abnormalities: (a) Haemorrhage and inflammation within the uterus; (b) haemorrhage and necrosis within the uterus; (c) thrombosis with blood vessels admixed with haemorrhage and necrosis and (d) thrombosed blood vessels with background haemorrhage and necrosis within the ovary.

Discussion

In obstetric patients, GAS is classically associated with puerperal sepsis. A specific form of necrotising fasciitis of the myometrium has been reported in the post-partum period, described as ‘necrotising myometritis’.1 We present a patient with antepartum necrotising myometritis, which has been rarely reported in the literature.

Epidemiology and pathophysiology of GAS in obstetric patients

The vaginal–rectal colonisation rate with GAS in late low-risk pregnancy is reported as 0.03%, whereas the colonisation rate for Group B streptococci is 20.1%.2 GAS is not considered part of the normal flora. The prevalence of peri-partum GAS infection is reported as 0.18% of total births and 1.4% in women with intra-partum or puerperal fever,3 with septic shock rarely a presenting feature. Epidemiologic studies to estimate the incidence of GAS infections from 1995 to 2000 in nine regions of the USA identified 87 cases of postpartum GAS infections, and concluded that an estimated 220 cases of GAS infections are occurring annually in the USA.4 Laboratory-based surveillance to analyse the rates of Group B streptococcal and Group A streptococcal infections has concluded that although invasive streptococcal infections did not appear to be more severe in pregnant or postpartum women, postpartum women had a 20-fold increased incidence of GAS and GBS, compared with non-pregnant women.5 The exact reason for this predilection is not clear. Out of the patients who develop puerperal GAS infections, 83% develop within the first week postpartum. The true incidence of first or second trimester GAS infection is unknown; however, it is certainly less compared with peripartum GAS infection.3

Perinatal streptococcal infections differ from puerperal infections in both pathologic and clinical features. Pathological features that have been described in perinatal streptococcal infections spread by blood stream include concentration of the organisms in the myometrial vessels, intervillous spaces and precapillary loose fibrous tissue surrounding the myometrium and chorioamnionitis. Pathological features described in patients with ascending streptococcal infections in the puerperal period include acute purulent endometritis, myometritis, pelvic cellulitis, septic thrombophlebitis, peritonitis and pelvic abscess.6

Most myometrial infections are due to ascending infection. However, there have been recent reports of myometrial infection secondary to upper respiratory tract infections.6,7 Udagawa et al. report eight patients with perinatal necrotising myometritis. None of these patients had premature rupture of membranes, endometritis or chorioamnionitis, thus ruling out ascending infection.7 They concluded that the most likely cause for the severe streptococcal necrotising myometritis in their patients was secondary to haematogenous spread from upper respiratory tract infection. Our patient presented with an upper respiratory tract infection and we believe that the uterine infection was secondary to haematogenous spread rather than ascending infection.

TSS in obstetric patients

Streptococcal TSS is an acute febrile illness that is caused by GAS. It begins with a mild viral-like prodrome and involves minor soft-tissue infection that may progress to a shock, multiorgan failure, and death. It has been defined as any group A streptococcal infection associated with the early onset of shock and organ failure.8 The case definition of streptococcal TSS was published by the Centres for Disease Control (CDC) in 1993 (Table 1).9 In 1998, Shimizu et al. proposed a modification to the CDC criteria, which they labelled as “Japanese Criteria”. The modified criteria proposed inclusion of central nervous system (CNS) symptoms in the term ‘multiorgan failure' and the criteria also require the disease to progress rapidly and the patient to be free from any conditions that might suppress the immune system.10 The portal of entry for streptococci could be vagina, pharynx, mucosa or skin in 50% patients, while in the rest the portal of entry remains undefined.11 Bacteria such as staphylococcus and streptococcus produce toxins that on their own can trigger a potentially harmful inflammatory response in people resulting in manifestations that are very similar to septic shock: fever, hypotension, and organ failure. The only real difference being that the toxins in TSS can result in a characteristic rash or erythema, which is rarely seen in septic shock. This characteristic macular rash (that may desquamate) forms one of the criteria for the diagnosis of TSS.

Table 1.

Case definition of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

| 1. Isolation of Group A Streptococci (Streptococcus Pyogenes) |

| A. From a normally sterile site (e.g. blood, CSF, pleural or peritoneal fluid, tissue biopsy, surgical wound, etc.) |

| B. From a nonsterile site (e.g. throat, sputum, vagina, superficial skin lesion, etc.) |

| 2. Clinical signs of severity |

| A. Hypotension: Systolic blood pressure ≤ 90 mm Hg in adults or<5th percentile for age in children |

| and |

| B. ≥2 of the following signs |

| a. Renal impairment: Serum creatinine ≥177 micromol/L (> = 2 mg/dL) for adults or greater than or equal to twice the upper limit of normal for age. In patients with preexisting renal disease, a ≥2-fold elevation over the baseline level. |

| b. Coagulopathy: platelets ≤100 × 109/L (≤100,000/mm3) or DIC defined by prolonged clotting times, low fibrinogen level, and the presence of fibrin degradation products |

| c. Liver involvement: Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or total bilirubin levels greater than or equal to twice the upper limit of normal for age. In patients with the preexisting liver disease, a ≥2-fold elevation over the baseline. |

| d. Adult respiratory distress syndrome defined by acute onset of diffuse pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxaemia in the absence of cardiac failure, or evidence of diffuse capillary leak manifested by acute onset of generalised oedema, or pleural or peritoneal effusions with hypoalbuminaemia |

| e. A generalised erythematous macular rash that may desquamate |

| f. Soft tissue necrosis, including necrotising fasciitis or myositis or gangrene |

| An illness fulfilling criteria 1 A and 2 (A and B) can be defined as a definite case. An illness fulfilling criteria 1B and 2 (A and B) can be defined as a probable case if no other etiology for the illness is identified. |

Note: Adapted from Stevens DL. Invasive group A streptococcal infections: the past, present and future. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 1994. 13(6): p. 561–6.

Only a small number of patients with streptococcal TSS have been reported during pregnancy.12 Perinatal streptococcal infection with TSS is associated with a high maternal and foetal mortality,7 and considering the high maternal and foetal mortality, it is important to consider the possibility of TSS and treat early and aggressively.

Estimates of the incidence of invasive GAS infection is up to 5 cases per 100,000 people annually; however, the incidence of severe infections as defined by presence of shock or organ failure is only one case per 100,000 population.13 This may suggest that host factors have an important role in the overall severity of infections. Contacts of patients with streptococcal TSS can develop wide varying manifestations ranging from asymptomatic colonisation to developing streptococcal TSS. Thus, the presence of a virulent strain is necessary but not sufficient to cause infections of various types.

The toxins responsible for the development of TSS include M-protein (type 1 and 3 being the most significant) streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin (types A, B and C) and streptococcal super antigens. It is suggested that susceptibility to GAS infection is probably inversely related to the quantity of specific antibody against virulence factors such as Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (SPEA) and M-protein.14 M-protein contributes to invasiveness through its ability to impede phagocytosis of streptococci by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL). Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins A, B and C are involved in inducing fever and activation of mononuclear cells to induce production of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, interleukin (IL) 1 and IL 6, which are responsible for the classical manifestations of TSS including fever, shock and organ failure. There is also strong evidence that these streptococcal toxins act as super-antigens and stimulate T cell responses.

Bacterial super-antigens are stable bacterial proteins that are the most potent known activators of the immune system. They bind to the Major Histocompatibility Complex class II molecules and preferentially activate T cells. The staphylococcal enterotoxin B is also known to bind the co-stimulatory molecule CD28; which explains the ability of these toxins to induce toxic immune response at extremely low concentrations. Lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin) primarily interacts with CD14 receptors on macrophages, and though endotoxin and bacterial super-antigens activate different parts of the immune system, they have been shown to operate synergistically, inducing very high levels of TNF, Interleukin-6, and interferon gamma. The lethal doses of both inducers were reduced significantly.15

There is significant variation in the molecular weight of M-protein derived from streptococcal isolates with the size ranging from 41 to 80 kDa.16 Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) is a cytotoxin that is present in the majority of the community acquired methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates. PVL toxin has a molecular weight of 32 kDa.17 The molecular weights of cytokines in severe sepsis are IL-1β (17 kDa), IL-6 (26 kDa), and IL-1ra (17–22 kDa), IL10 (35–40 kDa).18 For removing cytokines and toxins with molecular weights of 0.05 to 50 kDa, convection is a better technique than diffusion. The convective removal of a solute depends on transmembrane pressure, on molecular weight (MW) and structure of the solute, as well as on the cut-off point of the membrane, which averages 35–40 kDa.18 Considering this cut-off based on molecular weight, the PVL toxin can be cleared by CRRT (specifically haemofiltration), but toxins from streptococcal TSS will not be easily cleared by CRRT.

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) can also be used in management of TSS though the evidence is based on anecdotal experience and non-randomised low-powered studies. Expert opinion supports the use of IVIG in staphylococcal TSS and for severe invasive Group A streptococcal disease if other approaches have failed. Some studies have shown non-significant reduction in mortality.19,20 A recent retrospective study in a paediatric population concluded that the use of IVIG in streptococcal TSS was associated with increased costs but was not associated with improved outcomes.21 It is postulated that IVIG may act by various mechanisms including neutralisation of streptococcal toxins, inhibition of T-cell proliferation, and inhibition of other virulence factors such as TNF-alpha and IL-6.22–24

Antibiotic therapy

Streptococcus pyogenes remains highly susceptible to β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin; however, the aggressive GAS infections such as necrotising fasciitis respond less well to penicillin and are associated with high mortality.11 The reasons for treatment failure with penicillin include a high concentration of GAS organisms in deeper tissues and slowing of the growth of GAS organisms to a stationary phase.25 Such a transition of the GAS organism to a high concentration and stationary phase of growth results in loss of certain penicillin binding proteins and hence may be responsible for failure of treatment with pencillin.26 Experimental studies in mice have also demonstrated that penicillin is ineffective if delayed by more than two hours in patients with streptococcal myositis, whereas erythromycin and clindamycin achieved much higher survival rates.27

Clindamycin is currently recommended in the management of streptococcal TSS, and its greater efficacy in severe GAS infections may be due to several possible factors. Clindamycin is advocated because of its effectiveness despite a high inoculum of bacteria (the ‘Eagle effect’) and its reduction of toxin production by inhibition of protein synthesis.14 The “Eagle effect” or “paradoxical zone phenomenon”, first described by Henry Eagle, is a phenomenon used to describe paradoxical reduced effect of antibacterial agents (especially penicillin) at high doses when treating staphylococcal and streptococcal infections.25 This particular phenomenon could be due to a variety of mechanisms including reduced penicillin binding protein expression during the stationary growth phase, induction of bacterial resistance mechanisms, and self-antagonising the receptors to which penicillin is supposed to bind.28 Although GAS is extremely sensitive to penicillin, it may fail to eradicate the organism due to “Eagle effect”. In tissues with high concentrations of GAS, the organism may grow at a slower rate and penicillin-binding proteins may be downregulated resulting in failure of treatment. Clindamycin efficacy is not affected by inoculum size or stage of growth,27,28,29 and it suppresses bacterial toxin synthesis.30,31 It also facilitates phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes by inhibiting M-protein synthesis,31 and suppresses synthesis of penicillin binding proteins resulting in inhibition of cell wall synthesis.29 It also has a longer post-antibiotic effect than β-lactams such as penicillin.32 Schlievert et al. demonstrated in vivo that sub-inhibitory concentrations of clindamycin, erythromycin and fluoroquinolones suppressed toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1) in staphylococcal TSS while β-lactams such as nafcillin and cephalosporins increased measurable TSST-1 probably by lysis or increasing cell membrane permeability.33

A retrospective review of paediatric streptococcal infections demonstrated a failure rate of 68% if the children were treated with a β-lactam alone, and the review also noted that a favourable outcome was more likely if the patients were treated with a protein synthesis inhibiting antibiotic (e.g. clindamycin) compared to those who were treated with cell wall synthesis inhibiting antibiotic (e.g. penicillin) (83% vs. 14% had better outcomes when treated with clindamycin).34 Though a prospective randomised trial is lacking, clindamycin is strongly recommended along with a carbapenem or penicillin plus β-lactamase inhibitor (ticarcillin-clavulanic acid or piperacillin-tazobactam). The duration of antibiotic therapy needs to be individualised, but most patients should be treated for at least 10 days. The exact duration of antibiotics is based upon the severity of illness and clinical improvement.

Conclusion

Group A streptococcal infections are uncommon in obstetric patients; however, they can cause severe sepsis with complications. We present a case of necrotising myometritis, which is relatively unique in its antepartum timeline. Diagnosing concurrent TSS in severe GAS infections can be difficult, and it should be considered and treated early and aggressively; however the use of IVIG, whilst common practice is not strongly supported by the literature. Source control remains the cornerstone of treatment for septic shock; in this patient’s case, hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy were required. Concurrent antibiotic therapy needs to be carefully considered and clindamycin should be used in combination with a penicillin or carbapenem due to the potential for ineffective penicillin treatment.

Consent

Written permission for the publication of this report has been received from the patient

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Lurie S, Vaknine H, Izakson A, et al. Group A streptococcus causing a life-threatening postpartum necrotizing myometritis: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2008; 34: 645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead PB, Winn WC. Vaginal-rectal colonization with group A streptococci in late pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2000; 8: 217–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anteby EY, Yagel S, Hanoch J, et al. Puerperal and intrapartum group A streptococcal infection. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 1999; 7: 276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chuang I, VanBeneden C, Beall B, et al. Population-based surveillance for postpartum invasive group a streptococcus infections, 1995–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35: 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutscher M, Lewis M, Zell ER, et al. Incidence and severity of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae, group A Streptococcus, and group B Streptococcus infections among pregnant and postpartum women. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53: 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ooe K, Udagawa H. A new type of fulminant group A streptococcal infection in obstetric patients: report of two cases. Hum Pathol 1997; 28: 509–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Udagawa H, Oshio Y, Shimizu Y. Serious group A streptococcal infection around delivery. Obstet Gynecol 1999; 94: 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens DL, Tanner MH, Winship J, et al. Invasive group A streptococcal infections: the past, present and future. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1994; 13: 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Defining the group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Rationale and consensus definition. The Working Group on Severe Streptococcal Infections. JAMA 1993; 269: 390–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu Y, Igarashi H, Murai T, et al. Report of surveillance on streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in Japan and presentation of the criteria. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 1998; 72: 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stevens DL, Tanner MH, Winship J, et al. Severe group A streptococcal infections associated with a toxic shock-like syndrome and scarlet fever toxin A. N Engl J Med 1989; 321: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crum NF, Russell KL, Kaplan EL, et al. Group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome developing in the third trimester of pregnancy. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2002; 10: 209–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies HD, McGeer A, Schwartz B, et al. Invasive group A streptococcal infections in Ontario, Canada. Ontario Group A Streptococcal Study Group. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stevens DL. Invasive group A streptococcus infections. Clin Infect Dis 1992; 14: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blank C, Luz A, Bendigs S, et al. Superantigen and endotoxin synergize in the induction of lethal shock. Eur J Immunol 1997; 27: 825–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischetti VA. Streptococcal M protein: molecular design and biological behavior. Clin Microbiol Rev 1989; 2: 285–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko J, Kamio Y. Bacterial two-component and hetero-heptameric pore-forming cytolytic toxins: structures, pore-forming mechanism, and organization of the genes. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2004; 68: 981–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Vriese AS, Colardyn FA, Philippe JJ, et al. Cytokine removal during continuous hemofiltration in septic patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999; 10: 846–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norrby-Teglund A, Muller MP, Mcgeer A, et al. Successful management of severe group A streptococcal soft tissue infections using an aggressive medical regimen including intravenous polyspecific immunoglobulin together with a conservative surgical approach. Scand J Infect Dis 2005; 37: 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darenberg J, Ihendyane N, Sjölin J, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin G therapy in streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a European randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37: 333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah SS, Hall M, Srivastata R, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in children with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49: 1369–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norrby-Teglund A, Kaul R, Low DE, et al. Evidence for the presence of streptococcal-superantigen-neutralizing antibodies in normal polyspecific immunoglobulin G. Infect Immun 1996; 64: 5395–5398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norrby-Teglund A, Kotb M, Schwartz B, et al. Plasma from patients with severe invasive group A streptococcal infections treated with normal polyspecific IgG inhibits streptococcal superantigen-induced T cell proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol 1996; 156: 3057–3064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darenberg J, Soderquist B, Normark BH, et al. Differences in potency of intravenous polyspecific immunoglobulin G against streptococcal and staphylococcal superantigens: implications for therapy of toxic shock syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 836–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eagle H, Musselman AD. The rate of bactericidal action of penicillin in vitro as a function of its concentration, and its paradoxically reduced activity at high concentrations against certain organisms. J Experiment Med 1948; 88: 99–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eagle H. Experimental approach to the problem of treatment failure with penicillin. I. Group A streptococcal infection in mice. Am J Med 1952; 13: 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens DL, Yan S, Bryant AE. Penicillin-binding protein expression at different growth stages determines penicillin efficacy in vitro and in vivo: an explanation for the inoculum effect. J Infect Dis 1993; 167: 1401–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens DL, Gibbons AE, Bergstrom R, et al. The Eagle effect revisited: efficacy of clindamycin, erythromycin, and penicillin in the treatment of streptococcal myositis. J Infect Dis 1988; 158: 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan S, Bohach GA, Stevens DL. Persistent acylation of high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins by penicillin induces the postantibiotic effect in Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect Dis 1994; 170: 609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stevens DL, Maier KA, Mitten JE. Effect of antibiotics on toxin production and viability of Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1987; 31: 213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gemmell CG, Peterson PK, Schmeling D, et al. Potentiation of opsonization and phagocytosis of Streptococcus pyogenes following growth in the presence of clindamycin. J Clin Invest 1981; 67: 1249–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuenzi B, Segessenmann C, Gerber AU. Postantibiotic effect of roxithromycin, erythromycin, and clindamycin against selected gram-positive bacteria and Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother 1987; 20: 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlievert PM, Kelly JA. Clindamycin-induced suppression of toxic-shock syndrome–associated exotoxin production. J Infect Dis 1984; 149: 471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimbelman J, Palmer A, Todd J. Improved outcome of clindamycin compared with beta-lactam antibiotic treatment for invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999; 18: 1096–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]