Abstract

Biosimilar drugs are highly similar to an originator (reference) biologic, with no clinically meaningful differences in terms of safety or efficacy. As biosimilars offer the potential for lower acquisition costs versus the originator biologic, evaluating the economic implications of the introduction of biosimilars is of interest. Budget impact analysis (BIA) is a commonly used methodology. This review of published BIAs of biosimilar fusion proteins and/or monoclonal antibodies identified 12 unique publications (three full papers and nine congress posters). When evaluated alongside professional guidance on conducting BIA, the majority of BIAs identified were generally in line with international recommendations. However, a lack of peer-reviewed journal articles and considerable shortcomings in the publications were identified. Deficiencies included a limited range of cost parameters, a reliance on assumptions for parameters such as uptake and drug pricing, a lack of expert validation, and a limited range of sensitivity analyses that were based on arbitrary ranges. The rationale for the methods employed, limitations of the BIA approach, and instructions for local adaptation often were inadequately discussed. To understand fully the potential economic impact and value of biosimilars, the impact of biosimilar supply, manufacturer-provided supporting services, and price competition should be included in BIAs. Alternative approaches, such as cost minimization, which requires evidence demonstrating similarity to the originator biologic, and those that integrate a range of economic assessment methods, are needed to assess the value of biosimilars.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| For biosimilars, there is a paucity of robust, peer-reviewed publications of budget impact analyses (BIAs), a common tool in reimbursement decision-making. |

| Comprehensive BIAs based on robust evidence are needed to evaluate the affordability of biosimilars, while other types of economic evaluation are needed to assess the value of biosimilars. |

Introduction

Biologic drugs, also known as biopharmaceuticals or biological therapies, are genetically engineered proteins produced in living organisms such as bacteria, yeast, or human cell lines. Unlike generic small-molecule pharmaceuticals, which are identical to their originator, it is not possible for a different manufacturer to produce an identical copy of an originator biologic (also known as the ‘reference’ product) due to their large size, complex structure, and manufacture in a unique line of living cells [1]. Instead, a biologic deemed highly similar to a reference biologic is called a ‘biosimilar’.

In the USA, a biosimilar is defined as having “no clinically meaningful differences between the biosimilar product and the reference biologic in terms of safety, purity and potency” [2, 3]. Manufacturers are required to provide supporting evidence that it meets the standards for biosimilarity recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [4] when seeking marketing approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [5], European Medicines Agency (EMA) [6], or other national regulatory agencies. In contrast, ‘intended copies’ are copies of originator biologics that have not undergone rigorous comparative similarity evaluations in accordance with WHO recommendations, but are being commercialized in some countries outside Europe, the USA, or Canada. The weight of evidence available to support biosimilars is significantly greater than that for intended copies, as reported in a 2016 systematic literature review [7].

The first available biosimilars in Europe were human growth hormones, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factors [8]. The first monoclonal antibody biosimilar was approved in 2013 for infliximab. With loss of exclusivity of a number of monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins used in immunology and oncology occurring between 2015 and 2019, many new biosimilars are in development or recently available [9, 10], presenting decision-makers with an increasing number of biologic treatment options.

Experience from European markets, where biosimilar products were first introduced and have been available since 2006, has shown that many of these molecules are priced 10–30% lower than the originator biologic [8], although cost savings with monoclonal antibodies and fusion protein biosimilars have not been realized in all markets [9, 10]. Despite biosimilar availability in the USA lagging behind that in Europe, the US market for biosimilars is potentially the largest in the world. Biosimilars, and specifically the economic impact of these alterative drug options, are now entering into formulary decisions for US payers, as has been the case outside of the USA for over a decade. The expectation of achieving potentially significant health system cost savings stemming from competition among an increasing number of available biosimilars [9, 10] has led to widespread interest in developing modeling techniques that can accurately estimate the economic impact of biosimilar adoption.

Budget impact analysis (BIA) is one technique often used to complement other forms of economic evaluation. While some methods of economic evaluation consider the efficiency of healthcare resource allocation, BIA considers its affordability [11]. Since the 1990s, many countries have incorporated BIA into formulary listing or reimbursement decision-making [12].

In its recent good practice guidance, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) described the benefits and uses of BIA: “BIA addresses the expected changes in the expenditure of a health care system after the adoption of a new intervention…. A BIA can also be used for budget or resource planning. A BIA can be freestanding or part of a comprehensive economic assessment along with a CEA [cost-effectiveness analysis]” [12].

The main objective of a BIA is to assess the short-term (e.g., up to 3 years, with annual estimates), undiscounted financial consequences of the introduction of a new technology in a specific setting and from a specific payer perspective, taking into account healthcare resource trade-offs and future uncertainty [13]. BIAs may be conducted by pharmaceutical companies, independent academic groups, or by payers.

To assess the affordability of health technologies, such as biosimilars, payers use BIAs to support decision-making at national, regional, and local levels. Moreover, reimbursement authorities increasingly require these models as part of a formulary listing request or reimbursement submission. The importance of BIAs in decision-making varies by country and by stakeholder [14]. Despite their growing importance in healthcare decision-making, BIAs have not been widely published in the literature. A systematic review, published in 2014, reviewed BIAs of drugs in European Union settings published in English since 2008 [13]. The analysis found that few BIAs had been published and many, in the opinion of the authors, were of poor quality, relying on weak data sources. However, subsequent to that review, ISPOR published updated guidelines on BIAs [12], which may have positively affected the quality of BIAs conducted since the ISPOR guidelines were published.

Given the challenges of assessing the budget impact in the context of overall evaluation of biosimilars, this review examines the currently available published literature on BIAs for biosimilars of fusion proteins and monoclonal antibodies in chronic inflammatory disease and oncology. With the increasing number of newly approved biologic drugs in these therapeutic areas, decision-makers in multiple markets are presented with a growing number of agents to consider in formulary and reimbursement assessments. As BIAs focus on affordability rather than ‘value’, they are just one tool among several for assessing the overall value for money that budget holders consider as they contend with access policies for a range of competing conditions, each with multiple treatment options, among a diverse population. This analysis focuses on budget impact and primarily affordability, but it acknowledges that the value offered by new technologies such as biosimilars goes beyond budget affordability over a given time horizon.

In this review we:

assess whether the identified models are ‘fit for purpose’; i.e., in line with published guidelines for conducting BIAs and of sufficient utility to meet the needs of decision-makers;

provide recommendations to improve budget impact modeling and reporting in future BIA publications for biosimilars, to address typical payer and provider considerations; and,

introduce broader issues, concepts, and value assessment techniques that should be considered when moving beyond short-term affordability, to fully assess the true economic value of biosimilars.

Methods

Searches of published literature were conducted without date limitation in MEDLINE/MEDLINE In-Process and EMBASE on 30 June 2016. Searches included terms to capture fusion proteins and/or monoclonal antibodies, biosimilars, and BIAs. One reviewer evaluated titles and abstracts to identify English-language BIAs. A second reviewer was consulted when eligibility was unclear. In addition, ISPOR conference abstracts were hand-searched to identify relevant BIA publications.

In the absence of a formal ‘gold-standard’ checklist for evaluating the quality of BIAs, elements of the ISPOR good practice guidelines [12] were used to guide evaluation. A detailed list of factors for consideration in designing and evaluated BIAs, adapted from the ISPOR report, is provided in Table 1. Based on these recommendations, the following subset of criteria was used to assess BIA in this study: intervention, indication, country, time horizon, costs included (e.g., drug only vs. in addition to administration, monitoring, treatment-related adverse events, and savings from avoided healthcare utilization), uptake and price parameters, and assumptions and scenario analyses.

Table 1.

Factors for consideration in the evaluation of budget impact analyses [12]

| Factor | Examples |

|---|---|

| Scope of the analysis | |

| Perspective | Entire health system, regional/local health system, employer, service provider (e.g., hospital or pharmacy benefits manager), patient/household |

| Healthcare system | Single vs. multiple payer, universal or sub-segment coverage, healthcare coverage policy (e.g., 30-day hospital readmission), health technology access/reimbursement restrictions, patient co-pay requirements |

| Indications and population | Included groups, both by disease area/indication and by sub-population |

| Interventions | Included treatments and comparators, including standard of care (including no existing treatment), number of branded and unbranded technologies currently available or anticipated during time horizon, treatment mix |

| Model assumptions and data inputs | |

| Healthcare system population | Size, demographic composition, co-morbidities, severity, new vs. existing patients, expected length of time covered by payer, other sources of insurance (reflecting entire population for health plan) |

| Population eligible for intervention | Disease prevalence and incidence, naïve vs. treated patients, access restrictions (e.g., demographic, co-morbidities, biomarker, disease severity/stage or previous/concurrent treatment requirements), potential for use in ineligible populations |

| Technology uptake | Variation by specialty, country, region (state/province; urban/non-urban), health plan/payer type, mix of new and existing technology uptake, line of therapy, diagnostic requirements, availability of new interventions and impact on utilization patterns (e.g., substitution or in combination of standard of care or first treatment when only supportive care has been available), tolerability, adherence, persistence, resistance, off-label use (since no data, recommend excluding from budget impact analyses) |

| Estimated costs for modeled intervention mix | Acquisition costs, manufacturer rebates/incentives, disease- and adverse event treatment-related costs, payer vs. patient out-of-pocket costs; multiplied by eligible population |

| Model design | |

| Time horizon | 1 year common with US commercial payers; 3–5 years more likely to reflect avoided resource utilization and events and entry of new agents; ≥0 years captures long-term savings and additional entry of new agents; influence of model inputs and assumption will change with time horizon |

| Assumptions and methods to handle structural uncertainty | Use of simple linear rates vs. complex non-linear functions to reflect changes over time and among population subgroups or intervention types |

| Time dependencies and discounting | Changes in value of currency in model, uptake of evaluated intervention, timing and uptake of new technologies, price changes from competition and loss of exclusivity, provider and patient perceptions of disease and interventions, covered indications, treatment practices, discounting (recommended that none be applied in budget impact analyses) |

| Computing framework | Simple spreadsheet with cost calculator (recommended) vs. more complex simulation models |

| Validation | Face validity to include payer preferences for model assumptions and data inputs including source data, verification of all formulas used in cost calculator or simulation model, comparison of observed health plan costs with first-year budget impact estimates |

| Uncertainty and reporting | Scenario analyses to assess plausible alternate parameter and structural assumptions, transparency of assumptions, discussion of limitations |

Results

Review of the Published Literature

After initial screening, 16 publications reporting BIAs for biosimilar fusion proteins and/or monoclonal antibodies were identified, including three full papers and 13 congress abstracts. However, one full paper [16] had a title similar to a congress abstract published earlier by the same authors [17]. Similarly, a full paper by Jha et al. [18] reported an analysis similar to two earlier congress abstracts [19, 20]. In the current review, the full papers were selected for inclusion in the analysis over the preceding abstracts, which were omitted from the analysis to avoid duplication. An additional published BIA of an infliximab biosimilar was identified [21]; however, as it was published in Italian and the English-language abstract provided insufficient information for evaluation, it was excluded from this review. The remaining publications comprised three full papers plus nine abstracts presented as posters at conferences (all but one poster was obtained), for a total of 12 included publications. Characteristics of the included publications are summarized in Table 2. Table 3 reports the uptake and pricing parameters, including those to which the results were reported to be sensitive.

Table 2.

Characteristics of identified publications of budget impact analyses of biosimilar fusion proteins and monoclonal antibodies

| Study | Intervention | Indication | Country | Time horizon (years) | Perspective and costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full publications | |||||

| Brodszky et al. 2014 [15] | Biosimilar infliximab | RA | Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia | 3 | Payer (third-party) perspective Drug costs Administration costs Monitoring costs |

| Brodszky et al. 2016 [16] | Biosimilar infliximab | CD | Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia | 3 | Payer (third-party) perspective Drug costs Administration costs Monitoring costs |

| Jha et al. 2015 [18] | Biosimilar infliximab | RA, AS, CD, UC, PsA, psoriasis | Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, UK | 1 | Not stated; country-level budget impact perspective (third-party payer assumed) Drug costs All other costs (administration. monitoring, adverse events); assumed to be the same for biosimilar and reference infliximab |

| Posters | |||||

| Bocquet et al. 2015 [30] | Infliximab biosimilar | RA, GI, dermatology, other | Public hospitals in Paris, France | 1 and 3 | Payer (Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris; public hospital system) perspective Hospital drug cost |

| Kim et al. 2014 [22] | Infliximab biosimilar | RA | France, Germany, Italy, UK | 5 | Payer and patient perspectives (no further details given) Drug costs |

| Kim et al. 2015 [23] | Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 | CD | France, Italy, UK | 5 | Payer and patient perspectives (no further details given) Drug costs |

| McCarthy et al. 2013 [27] | Infliximab biosimilar CT-P13 | RA | Ireland | 5 | Not stated; country-level budget impact perspective (third-party payer) assumed Drug cost Administration cost Monitoring cost |

| Povero and Pradelli 2015 [31] | Infliximab biosimilar | Psoriasis | Italy | 3 | Payer (sistema sanitario nazionale [national health service]) perspective Drug cost |

| Ruff et al. 2015 [24] | Etanercept biosimilar | RA | France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK | 5 | Payer perspective Drug, administration, monitoring costs |

| Ruff et al. 2015 [25] | Etanercept biosimilar | RA, PsA, psoriasis, AS | France, Germany, Italy, Spain, UK | 5 | Payer perspective Drug, administration, monitoring costs |

| Shah and Mwamburi 2016 [32] | Infliximab biosimilar Adalimumab biosimilar |

RA | USA | 1 | Not stated; payer and patient perspectives assumed Annual healthcare costs Drug and administration costs |

| Whitehouse et al. 2013 [28] | Infliximab biosimilar Adalimumab biosimilar Etanercept biosimilar |

RA | France, Germany, UK | 1 | Not stated; payer and patient perspectives assumed Drug costs |

AS Ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, GI gastroenterology, PsA psoriatic arthritis, RA rheumatoid arthritis, UC ulcerative colitis

Table 3.

Summary of uptake, price parameters, and scenario analyses used in identified publications on budget impact analyses of biosimilars

| Study | Uptake parameters | Price parameters | Scenario analyses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full publications | |||

| Brodszky et al. 2014 [15] | Initial population treated with biologics taken from 2013 data Scenarios (assumptions): Only pts starting new biologic therapy can receive biosimilar 80% of pts on originator infliximab are interchanged to biosimilar, plus pts starting new biologic therapy can receive biosimilar Assumptions: 10% annual growth rate in biologics market Biosimilar infliximab used in 65%/25% (at end of first year) of pts for whom originator infliximab/non-infliximab TNFi would have been selected as first- or second-line drug New pts receiving biologics exactly compensated for pts leaving the model |

Assumption: biosimilar price is 75% of originator (i.e., 25% discount), based on retail prices, derived from official national price list in each country | Initial population treated with biologics Acquisition cost of biosimilar infliximab Population growth, discontinuation, and interchanging rates |

| Brodszky et al. 2016 [16] | Initial population treated with biologics taken from 2013 data Scenarios (assumptions): Only pts starting new biologic therapy can receive biosimilar 80% of pts on originator infliximab are interchanged to biosimilar, plus pts starting new biologic therapy can receive biosimilar Assumptions: 10% annual growth rate in biologics market Biosimilar infliximab used in 75%/25% (at end of first year) of pts for whom originator infliximab/adalimumab would have been selected as first- or second-line drug New pts receiving biologics exactly compensated for pts leaving the model |

Assumption: price of biosimilar is 75% of price of originator in all 6 countries | Number of the initial population treated with biologics Acquisition cost of biosimilar infliximab Population growth, discontinuation and interchanging rates |

| Jha et al. 2015 [18] | Number of pts eligible for infliximab under current prescribing practices based on disease prevalence and/or incidence rate in each country, grouped by pts currently treated with originator infliximab based on market data vs. infliximab-naive pts Assumptions: 25% of pts on originator infliximab switch to biosimilar infliximab 50% of infliximab-naive pts receive biosimilar infliximab |

Assumption: price of biosimilar infliximab is discounted 10, 20, or 30% relative to originator | Biosimilar price Number of pts treated, prevalence estimates, incidence Estimates, pts’ weight |

| Posters | |||

| Bocquet et al. 2015 [30] | Scenarios 1 and 2: tender between branded and biosimilar infliximab to list only one infliximab in hospital drug formulary Scenario 3: tender between branded and biosimilar infliximab for infliximab-naive pts only, with 10% of infliximab-naive pts treated with biosimilar infliximab if it wins the tender |

Scenario 1: biosimilar price 20% discount Scenario 2: biosimilar price 30% discount Scenario 3: biosimilar price 20% discount |

Results depend on scenario |

| Kim et al. 2014 [22] | Number of pts eligible for infliximab based on total population, annual population growth rate, and disease prevalence rates in each country Assumptions: Biosimilar has 25% market share in year 1 Biosimilar market share growth of 20, 30, or 40% per year |

Assumption: Price is discounted 10, 20, or 30% relative to originator |

Price and market uptake scenarios |

| Kim et al. 2015 [23] | Number of pts eligible for infliximab based on total population, annual population growth rate, and disease prevalence rates in each country Assumptions: Biosimilar has 25% market share in year 1 Biosimilar market share growth of 20, 30, or 40% per year |

Assumption: Price is discounted 10, 20, or 30% relative to originator |

Price and market uptake scenarios |

| McCarthy et al. 2013 [27] | Number of pts eligible for infliximab based on national population, disease prevalence/incidence rate, proportion of pts eligible for treatment with a biologic, and proportion receiving treatment with a biologic Assumptions: Annual growth rate 1.1% Maximum conversion of all existing and new infliximab pts to biosimilar infliximab in years 1–5 (‘maximum conversion’ not defined) |

Assumption: Price is discounted 20% relative to originator |

Conversion rates |

| Ruff et al. 2015 [24] | Pts naive to biologics, on stable treatment, and failing first biologic Assumption: Uptake from etanercept to the biosimilar of 5–40% (2016–2020) |

Assumptions: Anti-TNF price erosion 5% per year Biosimilar price is 10% or 25% discount |

Market uptake rates Discount to etanercept |

| Ruff et al. 2015 [25] | Pts naive to biologics, stable on or failing first biologic Assumption: Uptake from etanercept to the biosimilar of 5–40% |

Assumptions: Anti-TNF price erosion 5% per year Biosimilar price is 10% or 25% discount |

Market uptake rates Discount to etanercept |

| Povero and Pradelli 2015 [31] | Total substitution of infliximab with its biosimilars | Not stated | Not stated |

| Shah and Mwamburi 2016 [32] | Assumption: Biosimilar market share 30% of reference biologic |

Assumption: 25% cost discount |

Cost discount Market share |

| Whitehouse et al. 2013 [28] | Assumption: 50% of eligible pts |

Assumption: 30% cost discount |

Not stated |

pts Patients, TNF tumor necrosis factor, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

In six of the 12 included publications, at least one other publication was identified that had a common author(s), intervention, set of assumption, time horizon, and/or setting. These were deemed to be different versions of the same or similar core model, adapted for different countries and treatment settings. For example:

Brodszky et al. [16] stated that their BIA is an adaptation of the model in the earlier publication by Brodszky et al. [15].

Kim et al. [22] and Kim et al. [23] had the same pricing assumptions, time horizon (5 years), and market uptake assumptions.

Two 2015 publications by Ruff et al. appeared to be the same or very similar models of an etanercept biosimilar: one on rheumatoid arthritis [24] and one on rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis indications [25] for etanercept treatment in adults.

The literature searches identified two other review articles on BIAs, both focused on rheumatology, which were used to identify some of the BIA publications included in this review. Faleiros et al. [26] identified eight publications [15, 18, 22, 24, 25, 27–29] and Gulacsi et al. [29] identified three publications [15, 22, 27] in this review.

Are Current Published Budget Impact Models of Biosimilars Fit for Purpose?

A striking discovery of the current review was the apparent paucity of published data on BIAs for biosimilars. Only three full peer-reviewed papers were identified that presented budget impact models for biosimilar fusion proteins and/or monoclonal antibodies. Table 4 summarizes the three papers according to recommendations derived from the ISPOR 2014 guidelines [12]. A full assessment of the models presented in poster format was limited by the level of information available in each poster (all but one poster, which was authored by Kim et al. [23], were available and reviewed). Observations from these assessments have been included in the discussion, where relevant.

Table 4.

Full publications of budget impact models of biosimilars considered in relation to key aspects derived from the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research guidelines on budget impact assessments [12]

| Brodszky et al. 2014 [15] | Brodszky et al. 2016 [16] | Jha et al. 2015 [18] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope of the analysis | |||

| Features of the healthcare system | Difference in total direct costsa

The number of additional new pts who could be treated due to cost savings achieved |

Difference in total direct costsa

The number of additional new pts who could be treated due to cost savings achieved |

Difference in total drug costsa

The number of new pts who could be treated due to cost savings achieved |

| Perspective | Third-party payerb | Third-party payerb | Not specified: only drug costs considereda |

| Eligible population | Scenario 1: only pts starting new biologic therapya

Scenario 2: 80% of pts receiving originator infliximab are interchanged to biosimilar, plus pts starting new biological therapy |

Scenario 1: only pts starting new biologic therapya

Scenario 2: 80% of pts receiving originator infliximab are interchanged to biosimilar, plus pts starting new biologic therapy |

Infliximab-naïve and switch pts, those already receiving originator infliximab were considereda |

| Model design | |||

| Current intervention | Current intervention mix (including multiple biologics) taken from real-world 2013 market penetration data in each countryb | Current intervention mix (including originator infliximab and adalimumab) taken from real-world 2013 market penetration data in each countryb | Data on prevalence, incidence, and % drug-treated taken from the literature with IMS health data used to calculate number of pts on infliximaba |

| Uptake of new intervention and market effects | Included: substitution, combination, and expansionb | Included: substitution, combination, and expansionb | Included: substitution, combination, and expansionb |

| Off-label use of new intervention | Not includedb | Not includedb | Not includedb |

| Cost of current and new intervention mix | Included: costs of drugs, administration, and treatment monitoring multiplied by eligible populationb | Included: costs of drugs, administration, and treatment monitoring multiplied by eligible populationb | Included: model multiplied estimated cost per pt, based on dose, for each of the conditions and multiplied it by estimated eligible populationb |

| Condition-related costs | Not includedc | Not includedc | Not includedc |

| Indirect costs | Not includedb | Not includedb | Not includedb |

| Time horizon | 3 yearsb | 3 yearsb | 1 yearb |

| Choice of analytical computing framework | Not stateda | Not stateda | Excel®-based modelb |

| Uncertainty and scenario analyses | Scenarios of different price, uptake assumptions, and other parametersa | Scenarios of different price, uptake assumptions, and other parametersa | Partially included: scenarios of different price and population estimates and other parametersa |

| Validation | Validation not reportedc | Validation not reportedc | Validation not reportedc |

| Inputs and data sources | |||

| Size and characteristics of eligible population | Partially included: population size set on basis of real-world 2013 penetration dataa

Uptake and switching were based on assumptionsa |

Partially included: population size set on basis of real-world 2013 penetration dataa

Uptake and switching were based on assumptionsa |

Partially included: prevalence and incidence data taken from the published literaturea

Assumptions were made where data was not availablea |

| Intervention mix with and without the new intervention | Mix of real-world data and assumptions useda

Budget-holder data not useda |

Mix of real-world data and assumptions useda

Budget-holder data not useda |

Mix of real-world data and assumptions useda

Budget-holder data not useda |

| Cost of current and new intervention mix | Costs based on national price lists and assumptionsa

Budget-holder data not useda |

Costs based on national price lists and assumptionsa

Budget-holder data not useda |

Costs based on national price lists and assumptionsa

Budget-holder data not useda |

| Use and cost of other condition-related healthcare services | Administration and monitoring change included, size estimated, and value of changea

No health outcome changea |

Administration and monitoring change included, size estimated, and value of changea

No health outcome changea |

Drug-use change included, size estimated, and value of changea

No health outcome changea Administration and monitoring costs assumed to be the samea |

| Scenario analyses | |||

| Ranges and alternative values for scenario analyses | Partially includeda

Sensitivity analyses included using arbitrary ranges ± 10%a Expert opinion or published studies not used for rangesa |

Partially includeda

Sensitivity analyses included using arbitrary ranges ± 10%a Expert opinion or published studies not used for rangesa |

Partially includeda

Sensitivity analyses included using arbitrary ranges ± 10%a Expert opinion or published studies not used for rangesa |

ISPOR International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, pt(s) patient(s)

aPartially in line with ISPOR recommendations

bFully in line with ISPOR recommendations

cNot in line with ISPOR recommendations

Purpose and Perspective

The full papers by Brodszky et al. [15, 16] specified the setting, perspective (third-party payer), and patient population eligibility criteria in their evaluation of the budget impact of the biosimilar infliximab in six Eastern European countries, across several disease areas, from a third-party payer perspective (Table 2). Although not explicitly stated in Jha et al. [18], it can be inferred based on the text that the European country-level budget impact models presented were from a third-party payer perspective. Among the posters, BIAs were conducted from combined payer and patient perspectives in two studies by the same lead author [22, 23], from a payer perspective (specifics not provided) in two posters by the same lead author [24, 25], as well as from a public hospital system [30] and a national health service [31] perspective. Perspective was not explicity stated in the remaining three posters but, based on content, was assumed to be third-party payer [27, 28, 32] (Table 2). The purpose, intended interpretation, and target audience for the BIAs included in this review were less clear.

Range of Included Costs

The reviewed publications included a limited range of costs, including drug, administration, and monitoring costs [15, 16, 24, 25, 27], and drug costs only [18, 22, 23, 28, 30]. Povero and Pradelli [31] included costs associated with adverse events; Shah and Mwamburi [32] calculated cost per effectively treated patient by dividing total annual costs by the number of patients defined as effectively treated, using administrative claims data. Jha et al. [18] acknowledged the limitation of the assumption of equivalent administration and monitoring costs for biosimilar and originator infliximab. Brodszky et al. [15, 16] acknowledged the limitation of excluding societal costs. Although drug, administration, and monitoring costs may have been those of most interest to a third-party payer, consideration of other cost parameters, such as cost to the patient or societal cost offsets, would have allowed a wider application of the analysis.

Time Horizon

The time horizons of the included studies ranged from 1 to 3 years [15, 16, 18, 28, 30–32], with some of the posters reporting up to 5 years [22–25, 27]. The appropriate time horizon depends on the intended use and audience for the BIA; for example, a timeframe of 1 year may be relevant to US commercial payers to correspond with health plan enrollment and annual budget planning, although this time period would likely not capture longer-term benefits of treatment with biologics. However, the rationale for and limitations of the chosen time horizon were often absent from the publications. For example, those models that utilized a shorter time horizon did not account for new biologic entries (and subsequently their biosimilars), which may have impacted the findings.

Even when longer time horizons were used, few models considered the impact of other possible interacting factors, such as changes in price, practice patterns, uptake, and access to treatments over time. Discounting was not included in any of the three articles, and uncertainty over future changes in price or local discounting was a stated limitation [15, 16, 18]. Discounting and future price changes were not included in the poster publications [22, 23, 27, 28, 30–32] except by Ruff et al. [24, 25], who included an assumption on price erosion over the 5-year time horizon.

Use of Assumptions to Populate the Model

This analysis identified a series of limitations in the data sources used to populate the included BIAs for biosimilars. An earlier review of budget impact models in Europe also found that studies relied on weak sources, such as assumptions rather than actual evidence, to populate the models [13].

In particular, for BIAs, a paucity of robust current and future pricing information resulted in assumptions about biosimilar prices. These assumptions appeared to be relatively arbitrary, without supporting data to provide a rationale for the percentage discount (10–30%) applied to the price of an originator biologic [15, 16, 27, 28, 32], although some analyses did address uncertainty by using several price assumptions [18, 22–24, 30]. Moreover, in most models, there was an implicit assumption that drug prices would remain stable over time [15, 16]. This assumption may not have been realistic, as prices of originator biologics may fall in response to future competition [9] and, given the availability of lower-cost alternatives, hospitals may negotiate individual discounts from the list price [1].

Some publications lacked clear evidence to support uptake assumptions, such as initial market share, market share growth, practice patterns, percentage of patients switching from originator biologic to biosimilar, and the percentage of new patients prescribed biosimilar treatment. For example, Brodszky et al. [15] assumed 10% annual growth in the biologics market: 65% of patients who would have been prescribed originator infliximab as first- or second-line treatment would receive biosimilar infliximab (increasing linearly to the 65% assumption by the end of the first year and remaining unchanged to the end of the 3-year model) and 25% of patients who would have been prescribed a non-infliximab tumor necrosis factor inhibitor as first- or second-line treatment would receive biosimilar infliximab (see Table 3). The authors acknowledged the uncertainty and limitations surrounding these assumptions. Several publications stated that the results were sensitive to changes in pricing discount assumptions [15, 16, 18, 24, 25, 32] and/or market uptake assumptions [19, 24, 25, 32].

Another limitation is that authors generally did not consider a change in future practice patterns, which could be driven by increased utilization. Evidence from established biosimilar markets shows expansion of biologics usage to earlier-stage disease when biosimilars enter the market. This expansion is likely also to occur in the USA, although perhaps not to the same extent as in more established markets in the near-term [9]. For example, in Europe, access has been granted to biosimilars where access to the originator biologic was previously restricted mainly due to cost constraints [9]. Earlier treatment intervention is often linked to better outcomes, so effectiveness profiles may change over time. This improvement in outcomes has potential implications for treatment guidelines, health system costs, and guidance provided by Health Technology Assessment agencies, which may, in turn, further stimulate access and increase usage. Output from BIAs could be improved if assumptions for changes in practice patterns and utilization were incorporated in the methodology.

Discussion

Potential for Improvements in Budget Impact Modeling of Biosimilars

Currently available BIAs could be enhanced to make the included parameters more informative to decision-makers. Improvements include expanding the range of cost-input estimates, more robust data inputs, inclusion of sensitivity analyses, incorporating future market interactions, transparent methods and assumptions, and more-detailed reporting.

A wider selection of resource use and associated cost parameters could be incorporated to make BIAs for biosimilars more meaningful to providers and payers for decision-making. The cost of adverse events, increased or decreased hospitalization, office visits, and other healthcare services, such as medication administration or monitoring, could be included. The inclusion and exclusion of parameters assessed in a particular BIA require a clear rationale in relation to the disease area and the intended audience perspective of the BIA.

Use of more robust data sources for key parameters would improve predictive modeling of biosimilar usage. Real-world data on uptake, switching, and pricing are becoming available in some markets and should be utilized to improve the rigor and face validity of models going forward. Where use of assumptions is unavoidable, provision of a supporting rationale and validation of the assumptions with the relevant stakeholders are critical to improve transparency and reduce bias. The impact of uncertainty needs to be evaluated through sensitivity analysis.

Other factors likely to affect biosimilar uptake, and thus BIA assumptions, include practice setting, country, and prescriber understanding of and experience with biosimilars, which have been shown to vary with specialty. For example, a survey conducted between November 2015 and January 2016 of US physicians who prescribed biologics found that, among 1201 respondents, 50–57% of oncologists compared with 44% of gastroenterologists, 38% of dermatologists, and 35% of rheumatologists, agreed with the statement that biosimilars would be “safe and appropriate for use in [treatment]-naïve and existing patients” [33]. The evidence base for BIAs will require real-world utilization and outcomes data to be stratified by factors such as prescriber specialty, as well as by practice setting and country, to improve the predictive skill of BIAs for biosimilars.

Another consideration for BIAs (as well as for comprehensive value assessments) is that biologics and biosimilar drugs are not necessarily stand-alone products. For example, originator biologics and biosimilars may be associated with wrap-around services provided or supported by the manufacturer, such as specialist pharmacy services, patient access support mechanisms, and/or assistance with reimbursement administration. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, may offer a hub of support services such as reimbursement assistance for specialty therapies, patient follow-up and adherence services, and patient assistance programs to combine insurance payments with qualified financial assistance and co-pay programs. Genentech and Genzyme are cited as examples of companies using in-house teams, external vendors, and evolving technology platforms to provide support services to patients with rare diseases who receive lifelong high-cost medication necessary for disease management [34, 35]. These services may be less comprehensive for some biosimilars and may not be available at all for intended copies. Purchasing product from different manufacturers may also be associated with either more or less administrative burden than the originator biologic. Some of these factors could be incorporated into BIAs to more broadly reflect the costs and offsets of biosimilars.

Assessing Biosimilars Using Budge Impact Analysis: What Questions Should Payers Ask?

BIAs should provide sufficient transparency in describing the methodology and assumptions to be reproducible and should be updated as more information becomes available. Access to models that incorporate functionality for users to produce up-to-date customized analyses that represent their own environment and needs would provide the most utility.

In addition to ISPOR guidance, local organizations may have their own specific recommendations for the production of BIAs. For example, the National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC), a US-based biopharmaceutical industry member organization focusing on health policy research, based on evidence, value of medicines for patients, and innovation, has issued several recommendations on the use of budget BIA [36, 37], including the following:

Include all costs to and offsets in the healthcare system, not just medication costs.

Utilize timeframes long enough to incorporate all costs and cost offsets associated with the disease and patient management (e.g., some costs, such as avoided hospitalizations, may only become apparent in the longer term), including lower costs of medications when generics become available; examples could include 3 years to capture the costs of avoided hospitalizations or 10 years in keeping with the US Congressional Budget Office budget projections [38].

Include realistic estimates for all necessary inputs, incorporating information from stakeholders with expertise.

Conduct sensitivity analyses or report ranges around estimated results.

Several questions might be important to help payers and providers define the value of biosimilars and assess the usefulness of BIAs and other economic evaluations:

Is the totality of evidence (e.g., all available information, including a range of structural, functional, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamics, immunogenicity, effectiveness, and safety data) for biosimilar similarity satisfactory [39]?

Has the BIA considered all dimensions of health services resource use and associated costs relevant to the decision maker, e.g., the provision of specialist pharmacy services? Social services costs may also be relevant in this context.

How robust are the data sources used for the key parameters to which the results are sensitive? If some of the data sources are assumptions, can these assumptions be assessed against real-world data? Do they have face validity?

Is the timeframe adequate to demonstrate all aspects relevant to assessment of costs?

Are the key drivers, assumptions, and uncertainties (and reported ranges around estimated results) in the analysis, as well as the way in which these may influence interpretation and generalizability of the results, transparent and clearly stated?

Were BIA parameter inputs based on assumptions (e.g., assumptions of the number or percentage of patients starting or switching to a biosimilar) or was the BIA informed by actual real-world evidence?

Are assumptions around extrapolation of indications, use, and practice patterns for disease-specific treatments realistic? In other words, can payers predict the way in which the biosimilar will be used across disease areas?

If there are differences in the weight of the evidence base between products, e.g., in the amount of evidence provided to regulatory authorities or available from long-term data collection through surveillance systems, has this been taken into account in the evaluation?

When and how often should the BIA be updated? Is it considered a living model/analysis, including the latest evidence?

Challenges in Defining Value for Biosimilars

Budget impact addresses questions of affordability, given a series of model assumptions, and, on its own, does not assess ‘value’. Since biosimilars by definition are expected to have very similar efficacy and safety as the originator biologic, widely used cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses that incorporate health status such as in natural clinical units and quality-adjusted life-years, respectively, may not be well-suited to differentiate value among such similar comparators [9, 10]. The value of biosimilars might be better assessed using innovative value frameworks such as multi-criteria decision analysis, which objectively and transparently incorporate a broad range of value criteria beyond cost that may be important to diverse stakeholders [37, 40, 41].

For biosimilars that have demonstrated similarity to the originator in adequately powered similarity or non-inferiority studies, a cost-minimization approach would generally be appropriate, although definitions of ‘adequate evidence’ may vary by reimbursement authority. As a cost-minimization approach assumes equal efficacy and safety based on the available evidence, intended copies will not usually have sufficient evidence of similarity compared with the originator biologic to justify this approach. Reimbursement authorities may require different evidence of comparative effectiveness than that required for regulatory purposes, and important aspects of value for biosimilars cannot be captured within a cost-minimization analysis. Approved biosimilars with pharmacovigilance programs will generate additional real-world data that may inform value assessments.

Peripheral issues around manufacturing and maintenance of an inventory over a period of time have implicit value. Reliability of supply is important, particularly for biologics, when considering the value of a particular product for inclusion in a formulary. Drug shortages are an international problem that has increased in recent years. Inadequate supply can have multiple causal factors and far-reaching clinical, economic, and policy implications. Financial implications may include the additional resource spent sourcing alternative products and the additional cost of these alternative products, which can affect the pharmacist, manufacturer, reimbursement authority, and/or be passed on to the patient [42]. There is value associated with the efficient provision of medicines to patients, which requires the collaboration of authorization holders, manufacturers, wholesalers, dispensing doctors, pharmacists, and prescribers [43, 44]. Assessing the value of such additional services is important to stakeholders but presents a challenge with respect to capturing related cost offsets within the limitations of BIA or cost-minimization methodologies.

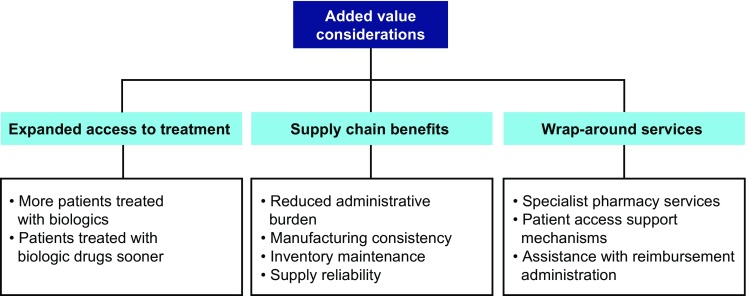

Widening access to treatments may also be of value. Several BIA publications state that the estimated budget savings gained by using biosimilars instead of originator biologics could be used to treat more patients [15, 16, 18, 24, 25, 27], or, alternately, enable budget reallocation for other diseases and treatment types [10]. Other types of outcomes research could capture more complex aspects of treatment sequencing and the impact on both costs and outcomes than BIA, but may still have limitations. Real-world studies designed to examine the impact and value of treating more patients who otherwise would not receive treatment (e.g., due to access limitations) by utilizing lower-cost biosimilars compared with originator biologics might demonstrate improved patient outcomes and societal value. In January 2016, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England and Wales published revised guidance for biologics, including biosimilars, for ankylosing spondylitis, hence widening previously restricted access when only originator biologics were available [45]. However, the value of this wider access, such as improved clinical effectiveness, is not incorporated fully in the context of BIA or cost minimization. Possible components of the value of biosimilars, in addition to affordability, are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Additional value considerations of biosimilars beyond budget impact

Furthermore, BIAs may incorporate future market interactions, competition, and pricing effects. Stakeholders are increasingly considering longer time horizons when contemplating the budget impact of chronic disease therapies. The Preventive Health Savings Act in the USA, proposed in 2015, states that bodies such as the Congressional Budget Office should consider longer-term impact, up to 10 years, rather than shorter time horizons [23].

This review identified several analyses that did not specifically fit the BIA definition but reported alternative approaches to assessing the economic impact of biosimilars. Rémuzat et al. [46–49] and others have used alternative innovative approaches to assess the budget impact of future market developments, including the entry of biosimilars. The authors forecast the impact of factors, including biosimilar entry, generic entry, exclusive hospital distribution, and national access policies, on overall pharmaceutical expenditure. Similarly, Mulcahy et al. [50] incorporated a more complex analysis of the biosimilar market, including consideration of payment models, non-price competition from originator biologics, regulatory uncertainty, and the indirect impact of broader biologic use on health and cost. Other reports also highlight the complexity of the biosimilar market. Blackstone and Joseph [51] emphasized the likelihood of alliances and partnering in the biosimilar market and noted that many factors, including safety, pricing, manufacturing, entry barriers, physician acceptance, and marketing, may affect uptake in the USA compared with other countries. Mestre-Ferrandiz et al. [52] highlighted the important role of the payer in generating incentives that encourage high-quality outcomes data and price competition for biosimilars. Factors such as expected price competition from originator biologics and other biosimilars, and uncertain acceptance and uptake, may reduce the incentive for companies to develop biosimilars, which could limit competition [53].

It is important to consider the different perspectives of the budget impact of biosimilars and identify which stakeholders may benefit from the cost savings. Although the BIAs included in this review primarily focused on a national level of health service costs, it is important to consider the savings to other stakeholders, such as patients, private insurers, public insurers, employers, and pharmacy benefit managers [54].

However, as acknowledged by Whitehouse et al. [28], BIAs can only capture economic expenditures incurred from using biosimilars; the effect on patient outcomes or societal benefits from increased access to biologic treatments needs to be addressed by further research. Future studies are required to assess the impact that biosimilars may have on wider aspects of healthcare, such as earlier access, patient outcomes, and treatment guidelines.

Study Limitations

Challenges in comparing BIA results included use of different units for presenting budget impact results, including absolute cost, impact (US dollars), relative cost impact (%), savings per year, savings per treatment, savings for total population, savings for a hypothetical panel of 1000 patients, and savings depending on percentage price reduction of biosimilar versus reference product. This review also had several limitations. First, it did not include BIAs in the public domain published in languages other than English. We identified one BIA of an infliximab biosimilar from Italy [21], which was not included in this review. An English summary of this BIA is available in a 2016 ISPOR presentation by Drummond and Martin [10]. Second, as with all reviews, studies published after the study cut-off date (30 June 2016) were not included, namely a BIA of trastuzumab in Croatia [55]. Third, this review did not include other types of economic analyses of biosimilars, such as cost-utility or cost-effectiveness analyses. An additional limitation was the paucity of BIAs published as peer-reviewed articles. Nine of the 12 publications identified in this review were in poster format, providing limited detail and impeding our ability to assess the methodology or extent to which reproducibility for local payer adaptation might be possible. Poster format also limited transparency, including reporting of the purpose of the analysis and its context, strengths, and limitations. Without these important details, the ability to interpret the information meaningfully from posters was limited and therefore the data in the published articles were most useful. It is uncertain why relatively few BIAs for monoclonal antibodies or fusion protein biosimilars have been published in the peer-reviewed literature, but it may be that the primary purpose of the BIAs is to secure reimbursement or preferred formulary placement and thus dissemination as a publication may be of low priority.

Conclusions

This literature review has identified a paucity of peer-reviewed information on the budget impact of biosimilar products. Only three full-text publications of BIAs for biosimilar fusion proteins or monoclonal antibodies were identified in the literature. Although these publications generally adhered to published guidance on conducting BIAs [12], this review identified considerable limitations in terms of the range of included costs and reliance on assumptions instead of robust data where model inputs were reported. The resulting estimates of budget impact were sensitive to these assumptions and these shortcomings highlight the need for additional information in the public domain regarding BIAs for biosimilars of monoclonal antibodies and fusion proteins as these products increasingly become available. The limitations of BIA for assessing pharmaceutical products in general have previously been reported [13]. Better BIA reporting would do much to improve the utility and reproducibility of these models, either through provision of more comprehensive information within the publication or of supplementary materials or links to additional content in posters, where space is at a premium.

Published guidance distinguishes BIAs as a tool primarily for assessing affordability, while other frameworks are designed to assess value [37]. The ISPOR guidelines state that the intended use of a BIA includes addressing the expected changes in healthcare system expenditures after the adoption of a new intervention, as well as budgeting or resource planning [12]. Thus, although well-conducted BIAs, in line with published guidance, form an important part of affordability evaluation, other complementary assessments are required to demonstrate the value of biosimilars.

Further research and novel approaches for assessing the incremental value of biosimilars are warranted, including incorporating more aspects of value than simply the difference in future spending on biosimilar products compared with biologics. Although several BIAs in this review evaluated the role of budget savings from less expensive biosimilars and expanding patient access to biologics in general, it is clear that BIAs on their own are inadequate to fully evaluate the economic impact of changes in treatment patterns, pricing, and market dynamics [46, 53].

Also of note, most clinical and payer experience with biosimilars stems from European countries that have a single-payer mechanism. In the USA, the implications of biosimilar utilization can be expected to differ as the market is categorized by multiple payers and greater fluidity, both in terms of formulary structure and patients’ choice of different health plans.

Although biosimilar uptake outside of the USA can provide some insight, the unique nature of the US market undoubtedly will result in different interpretations of the value of biosimilars. BIAs are one tool of many for assessing the impact of biosimilars on healthcare costs and quality. However, the paucity of published data on the budget impact of biosimilars limits interpretation, and additional economic models of biosimilars are needed to assess the range of their potential budget impact on the US healthcare system.

Acknowledgements

This review was supported by Pfizer, Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Carole Jones, MBA, and Karen Smoyer, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions and funded by Pfizer Inc.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to content development, writing, and critical review of the paper. IJ is the overall guarantor.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Steven Simoens is one of the founders of the KU Leuven Fund on Market Analysis of Biologics and Biosimilars following Loss of Exclusivity. Steven Simoens is conducting biosimilar research sponsored by Hospira (now Pfizer Inc.), is leading a stakeholder roundtable on biosimilars sponsored by Amgen, MSD, and Pfizer Inc., and has participated in an advisory board meeting on biosimilars for Pfizer Inc. Ira Jacobs, Robert Popovian, and Lesley G. Shane are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc. Leah Isakov is an employee of Seqirus, a CSL company, and was an employee and stockholder of Pfizer Inc. when this review was conducted.

Data Availability

The data used in this study were obtained from publically available manuscripts, congress abstracts, and congress posters as listed in the References section of this article.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required because this work is a review and did not involve the use of human patients or animal subjects.

Funding

This study and preparation of this manuscript were funded by Pfizer Inc.

Footnotes

Leah Isakov was an employee of Pfizer at the time this review was conducted.

References

- 1.Simoens S. Biosimilar medicines and cost-effectiveness. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;3:29–36. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S12494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Government. Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCI Act). 2009. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/. Accessed 4 Aug 2016.

- 3.US Government. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act)—amendment of section 351 of the Public Health Service Act. 2010 (last update: 28 Jun 2012). http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-law/read-the-law/. Accessed 4 Aug 2016.

- 4.World Health Organisation, Expert Committee on Biological Standardization. Guidelines on evaluation of similar biotherapeutic products (SBPs). 2009 (last update: 19 to 23 Oct 2009). http://www.who.int/biologicals/areas/biological_therapeutics/BIOTHERAPEUTICS_FOR_WEB_22APRIL2010.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

- 5.US Food and Drugs Administration. Scientific considerations in demonstrating biosimilarity to a reference product. Guidance for industry. 2015. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM291128.pdf. Accessed 4 Aug 2016.

- 6.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. CHMP/437/04 Rev 1. 2014 (last update: 30 Feb 2015). http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2014/10/WC500176768.pdf. Accessed 4 Aug 2016.

- 7.Jacobs I, Petersel D, Shane LG, et al. Monoclonal antibody and fusion protein biosimilars across therapeutic areas: a systematic review of published evidence. BioDrugs. 2016;30(6):489–523. doi: 10.1007/s40259-016-0199-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farfan-Portet M-I, GerkensIsabelle S, Lepage-NefkensIrmgard I, et al. Are biosimilars the next tool to guarantee cost-containment for pharmaceutical expenditures? Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(3):223–228. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0538-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Delivering on the potential of biosimilar medicines: the role of functioning competitive markets. 2016. http://www.imshealth.com/files/web/IMSH%20Institute/Healthcare%20Briefs/Documents/IMS_Institute_Biosimilar_Brief_March_2016.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

- 10.Drummond M, Martin M. Biosimilar value generation or value destruction? A workshop demonstrating uptake to date and quantifying savings made. In: 19th Annual European Congress of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research (ISPOR); 2 Nov 2016; Vienna.

- 11.Trueman P, Drummond M, Hutton J. Developing guidance for budget impact analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2001;19(6):609–621. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200119060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis-principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 2014;17(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Vooren K, Duranti S, Curto A, Garattini L. A critical systematic review of budget impact analyses on drugs in the EU countries. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12(1):33–40. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilsdon T, Serota A, Charles River Associates. A comparative analysis of the role and impact of health technology assessment. 2011 (last update: May 2011). http://www.efpia.eu/uploads/Modules/Documents/hta-comparison-report-updated-july-26-2011-stc.pdf. Accessed 4 Aug 2016.

- 15.Brodszky V, Baji P, Balogh O, Pentek M. Budget impact analysis of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in six Central and Eastern European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15(Suppl. 1):S65–S71. doi: 10.1007/s10198-014-0595-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brodszky V, Rencz F, Pentek M, et al. A budget impact model for biosimilar infliximab in Crohn’s disease in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(1):119–125. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1067142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodszky V, Gulacsi L, Balogh O, et al. Budget impact analysis of biosimilar infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in six Central Eastern European countries [poster] Value Health. 2014;17(7):A364. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jha A, Upton A, Dunlop WC, Akehurst R. The budget impact of biosimilar infliximab (Remsima®) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases in five European countries. Adv Ther. 2015;32(8):742–756. doi: 10.1007/s12325-015-0233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha A, Upton A, Dunlop W. Budget impact analysis of introducing biosimilar infliximab for the treatment of auto immune disorders In five European countries [poster] Value Health. 2014;17(7):A525. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.08.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh A, Jha RK, Mazumder D, Kapoor A. Role of budget impact analysis in market access of biosimilars [poster no. PHP85] Value Health. 2015;18(7):A529. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.1640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucioni C, Mazzi S, Caporali R. Budget impact analysis of infliximab biosimilar: the Italian scenery [in Italian] GRHTA. 2015;2(2):78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J, An Hong J, Kudrin A. Five-year budget impact analysis of biosimilar infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in UK, Italy, France and Germany [abstract no. 1166]. America College of Rheumatology/American Rheumatology Health Professionals (ACR/ARHP); 14–16 Nov 2014; Boston.

- 23.Kim J, An Hong J, Kudrin A. 5 Year budget impact analysis of CT-P13 (infliximab) for the treatment of Crohn’s disease in UK, Italy and France [poster no. P137]. In: 10th Congress of the European Crohn’s Disease and Colitis Organisation (ECCO); 18–21 Feb 2015; Barcelona.

- 24.Ruff L, Rezk MF, Uhlig T, Gommers JW. Budget impact analysis of an etanercept biosimilar for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Europe [poster no. PMS33]. In: 18th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Pharmaceconomics Outcome Research (ISPOR); 7–11 Nov 2015; Milan.

- 25.Ruff L, Rezk MF, Uhlig T, Gommers JW. Budget impact analysis of an etanercept biosimilar for the treatment of all licensed etanercept indications for adults in Europe [poster no. PMS31]. In: 18th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Pharmaceconomics Outcome Research (ISPOR); 7–11 Nov 2015; Milan.

- 26.Faleiros DR, Álvares J, Almeida AM, et al. Budget impact analysis of medicines: updated systematic review and implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(2):257–266. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2016.1159958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy G, Ebel Bitoun C, Guy H. Introduction of an infliximab biosimilar (CT-P13): a 5-year budget impact analysis for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in Ireland [poster no. PMS22] Value Health. 2013;16:A558. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.1465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitehouse J, Walsh K, Papandrikopoulou A, Hoad R. The cost saving potential of utilizing biosimilar medicines in biologic naive severe rheumatoid arthritis patients [poster no. PMS104] Value Health. 2013;16:A573. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.1547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulacsi L, Brodszky V, Baji P, et al. Biosimilars for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: economic considerations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11(Suppl. 1):S43–S52. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.1090313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bocquet F, Fusier I, Cordonnier A, et al. Budget impact analysis of implementing tenders between the branded infliximab and its biosimilars in the public hospitals of Paris [poster no. PMS30] Value Health. 2015;18(7):A639. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Povero M, Pradelli L. Biologic treatments for moderate to severe naïve psoriatic patients: a budget impact analysis in Italy [poster no. PSY30] Value Health. 2015;18:A663–A664. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.09.2414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah A, Mwamburi M. Modeling the budget impact of availability of biosimilars of infliximab and adalimumab for the treatment for rheumatoid arthritis using published claim-based algorithm data in the United States [poster no. PMS22]. In: 21st Annual Meeting of the International Society for Pharmaceconomics Outcome Research (ISPOR) 21–25 May 2016; Washington, DC.

- 33.Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33(12):2160–2172. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0431-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basta N. Finding the ‘HUB’ in specialty pharmacy services. 2013 (last update: 18 September 2013). http://pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/special-report/finding-the-hub-in-specialty-pharma-services/. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

- 35.Anbil P, Desai R. Specialty service programs: gearing up for next generation technologies. 2013. http://www.pharmexec.com/specialty-service-programs-gearing-next-generation-technologies. Accessed 22 Sep 2016.

- 36.National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC). The third rail—why budget impact assessments are not measures of value. 2016. http://www.npcnow.org/blog/third-rail-why-budget-impact-assessments-are-not-measures-value. Accessed 22 Jun 2017.

- 37.National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC). Value assessment frameworks. 2016. http://www.npcnow.org/issues/value/measuring-value/value-assessment-frameworks. Accessed 22 Jun 2017.

- 38.Congressional Budget Office. Outlook for the budget and the economy. 2017. https://www.cbo.gov/topics/economy/outlook-budget-and-economy. Accessed 5 Jun 2017.

- 39.US Food and Drugs Administration. Scientific considerations in demonstrating biosimilarity to a reference product. Guidance for industry. 2015 (last update: April 2015). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm291128.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2017.

- 40.Drummond M, Tarricone R, Torbica A. Assessing the added value of health technologies: reconciling different perspectives. Value Health. 2013;16:S7–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irwin J, Peacock S. Multi-criteria decision analysis: an emerging alternative for assessing the value of orphan medicinal products. Regul Rapporteur. 2015;12:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Weerdt E, Simoens S, Casteels M, Huys I. Clinical, economic and policy implications of drug shortages in the European Union. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40258-016-0264-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.European Parliament, Council on the Community Code. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code relating to medicinal products for human use. 2004 (last update: 28 Nov 2004). http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2009/10/WC500004481.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

- 44.Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Best practice for ensuring the efficient supply and distribution of medicines to patients. 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213290/distribution_medicines_V2.pdf. Accessed 23 Jun 2017.

- 45.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). TNF-alpha inhibitors for ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta383/chapter/1-Recommendations. Accessed 22 Sep 2016.

- 46.Rémuzat C, Toumi M, Cetinsoy L, et al. Innovative methodology for pharmaceutical expenditure forecast [poster no. PHP71] Value Health. 2013;16:A256. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.114th US Congress. H.R.3660 - To amend the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 respecting the scoring of preventive health savings. 114th Congress (2015–2016). https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/3660. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

- 48.Rémuzat C, Toumi M, Vataire AL, et al. Pharmaceutical expenditure forecast model to support health policy decision making [poster no. PHP68] Value Health. 2013;16:A255. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rémuzat C, Toumi M, Vataire AL, et al. EU pharmaceutical expenditure forecast [poster no. PHP64] Value Health. 2013;16:A254–A255. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.03.1302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulcahy AW, Predmore Z, Mattke S. The cost savings potential of biosimilar drugs in the United States. 2014. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE100/PE127/RAND_PE127.pdf. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

- 51.Blackstone EA, Joseph PF. The economics of biosimilars. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6:469–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mestre-Ferrandiz J, Towse A, Berdud M. Biosimilars: how can payers get long-term savings? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:609–616. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0380-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Araújo FC, Gonçalves J, Fonseca JE. Pharmacoeconomics of biosimilars: what is there to gain from them? Current Rheumatol Rep. 2016;18(8):50. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0601-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amundsen Consulting, IMS Health. A White Paper. Biosimilars: who saves? How similar molecules may mean similar cost-sharing for patients. 2016. https://structurecms-staging-psyclone.netdna-ssl.com/client_assets/dwonk/media/attachments/57dc/387d/6970/2d6c/ad6f/0000/57dc387d69702d6cad6f0000.pdf?1474050173. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

- 55.Cesarec A, Likić R. Budget impact analysis of biosimilar trastuzumab for the treatment of breast cancer in Croatia. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):277–286. doi: 10.1007/s40258-016-0285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from publically available manuscripts, congress abstracts, and congress posters as listed in the References section of this article.