Abstract

Liver transplantation (LT) has become standard of care in patients with non-resectable early stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in liver cirrhosis. Currently, patient selection for LT is strictly based on tumor size and number, provided by the Milan criteria. This may, however, exclude patients with advanced tumor load but favourable biology from a possibly curative treatment option. It became clear in recent years that biological tumor viability rather than tumor macromorphology determines posttransplant outcome. In particular, microvascular invasion and poor grading reflect tumor aggressiveness and promote the risk of tumor relapse. Pretransplant biopsy is not applicable due to tumor heterogeneity and risk of tumor cell seeding. 18F-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), an established nuclear imaging device in oncology, was demonstrated to non-invasively correlate with unfavorable histopathologic features. Currently, there is an increasing amount of evidence that 18F-FDG-PET is very useful for identifying eligible liver transplant patients with HCC beyond standard criteria but less aggressive tumor properties. In order to safely expand the HCC selection criteria and the pool of eligible liver recipients, tumor evaluation with 18F-FDG-PET should be implemented in pretransplant decision process.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Liver transplantation, 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, Tumor biology, Tumor recurrence

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequent primary liver tumor and its disease burden is significantly increasing in recent years. Currently, it is the fifth most common cancer and the third most common reason of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1,2 Major hepatic resection is mainly limited by underlying cirrhosis and liver dysfunction. Apart from that, tumor recurrence rates up to 75% have been reported following surgical treatment.3,4 From an oncological point of view, orthotopic liver transplantation (LT) offers best option of curation, since it removes both the tumor with widest possible surgical margins and the tumor-generating liver cirrhosis.5 However, early experiences more than two decades ago were hampered by unacceptably high tumor recurrence rates (32%–54%) and poor survival (5-year survival 20%–40%).6–8 In 1996, Mazzaferro et al. reported on excellent prognosis in 48 patients with a single HCC nodule up to 5 cm, or a maximum of 3 tumor nodules, each not exceeding 3 cm, and absence of macrovascular invasion. Four-year overall and recurrence-free survival rates were 85% and 92% for patients meeting the so-called Milan criteria (MC), but only 50% and 59% for those exceeding them.9 By strictly adhering to the MC, post-LT prognosis was shown to be comparable to LT in non-malignant diseases.10–13 Consequently, the MC have been incorporated as standard for selecting suitable liver transplant candidates in the United Network for Organ Sharing and the Eurotransplant region. Based on the model of end-stage liver disease score, patients with HCC meeting the MC are currently prioritized by exceptional waiting list points, in order to realize timely organ allocation.14,15

In recent years, the MC were increasingly criticised for being too conservative and, thereby, for refraining a significant number of patients from a possible curative treatment option.16 Apart from that, discrepancies between radiographic and histopathologic tumor staging additionally limited clinical applicability.17,18 Therefore, many expanded HCC criteria sets were recently proposed. Yao et al. introduced 2001 the so-called University of California San Francisco (UCSF) criteria (a single tumor up to 6 cm, or up to 3 tumor nodules, each not exceeding 4.5 cm in diameter and total tumor diameter up to 8.5 cm). One and 5-year recurrence-free survival rates were 98.6% and 96.7% in patients meeting, but only 80.4% and 59.5% in those exceeding them.19 In 2008, Herrero et al. reported on acceptable outcome in LT for one HCC nodule up to 6 cm, or up to 3 tumor nodules each not exceeding 5 cm in size, when macrovascular invasion and extrahepatic tumor disease were absent.12 More recently, Mazzaferro et al. proposed the so-called “Up-to-seven” criteria (UTS; sum of maximum size of the largest tumor in cm and the number of tumors). Based on histopathologic reports of 1112 liver recipients, the authors demonstrated a comparable 5-year posttransplant outcome between patients meeting the MC (73.3%) and those fulfilling the UTS criteria (71.2%), when microvascular invasion (MVI) was absent. In contrast, tumor-free survival rate was only 48.1% at 5 years in patients exceeding the UTS criteria.20 However, the study was based on postoperative histopathologic and not on preoperatively available clinical findings.20

It is nowadays generally accepted that the MC have to be liberalized in order to increase the number of HCC patients that may benefit from LT. However, it is still unclear how far the selection limits may be pushed without excessively increasing the risk of tumor relapse. Currently, a minimum survival probability between 50% and 60% at 5 years post-LT is demanded in order to balance benefit and harm of LT beyond standard criteria.21 In the so-called Metrotricket concept, Mazaferro et al. demonstrated a linear adverse prognostic impact of tumor size, whereas this negative effect tended to stagnate for tumor numbers beyond 3. With other words: when moving beyond the MC, the risk of HCC recurrence is increasingly determined by tumor biology rather than macromorphology.20

Currently, MVI and low tumor differentiation are recognized as most important predictors of biological tumor aggressiveness and poor outcome, along with serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level and response to neoadjuvant locoregional tumor treatment (LRTT).22–24 Although tumor size and number may correlate with MVI and grading, they only inaccurately describe biological behavior of HCC.25 Pretransplant biopsy is not applicable, due to tumor heterogeneity and the theoretical risk of tumor cell seeding and bleeding.26,27 Therefore, for safely expanding the macromorphometric tumor burden limit, reliable non-invasive clinical surrogate markers of aggressive tumor properties are essential. Apart from different serologic features (AFP; des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin; yglutamyltransferase; protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist II), in particular 18F-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) was recently shown to correlate with unfavorable biological behavior and poor outcome.22,28 This review reports on current available data about the prognostic impact of 18F-FDG-PET in liver transplant patients with HCC, with a special focus on possible implications for expanding the HCC transplant criteria.

18F-FDG-PET for metabolic evaluation and staging of HCC

PET is a well-established non-invasive diagnostic tool for metabolic staging and monitoring of chemo- or radiotherapy of different malignancies.29,30 Nowadays, it is combined with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for increasing diagnostic accuracy. The most commonly used tracer in oncology is 18F-FDG, which is a glucose analogue. Tumor imaging with this tracer is based on the principle of enhanced glucose metabolism in cancer cells. Like glucose, 18F-FDG is uploaded by the tumor cells via several overexpressed glucose transporters. In normal liver tissue, activity of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphatase, which converts FDG-6-P to FDG is high, whereas it is very low in liver metastasis, resulting in an increased FDG uptake pattern on PET scan. In contrast, the enzyme activity varies considerably among different types of HCC: Well differentiated HCC nodules exhibit an enzyme activity that is comparable to normal liver tissue. Therefore, low grade tumors tend to have a similar FDG uptake pattern than the surrounding normal liver tissue, finally leading to a low standard uptake value (SUV). On contrary, increased FDG uptake may be visualized in poorly differentiated HCC. Consequently, several studies have reported only a modest (below 50%) sensitivity of 18F-FDG-PET for diagnosing HCC.31–34 Although 18F-FDG-PET/CT is currently not recommended as first line diagnostic tool in suspected HCC, it may be useful for detecting and monitoring moderate to poorly differentiated HCC lesions, advanced stage HCC and extrahepatic metastases by a one-stop non-invasive metabolic imaging. Thus, initial tumor staging and treatment recommendations may change.35–37

Apart from that, 18F-FDG uptake on PET may provide useful information on biological tumor behavior. In a series of 48 HCC patients, Shiomi et al. demonstrated that the tumor-volume doubling time, an indicator of aggressive tumor growth, correlated significantly with PET results.38 Lee et al. showed that increased 18F-FDG uptake on PET was not only associated with poor tumor differentiation but also with overexpression of pro-cancerogenic gene profiles.39 Thus, important information on prognosis may be delivered by 18F-FDG-PET. In a current meta-analysis including 22 studies and a total of 1721 HCC patients, SUV and tumor-to-non tumor SUV ratio on pre-treatment 18F-FDG-PET both correlated with poor outcome.40

In recent years, several new radiotracers, such as 11C-acetate, were introduced for improving sensitivity and specificity. Despite promising early experiences, dual tracer PET/CT did not yet emerge to a popular diagnostic device in clinical routine.41,42

18F-FDG-PET for predicting tumor viability following LRTT

Response to neoadjuvant LRTT, such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radiofrequency ablation, is regarded as one of the most important clinical predictor of favorable outcome following LT for HCC.22,43 Patients with HCC initially exceeding the MC but responding to neoadjuvant LRTT by downsizing or downstaging were shown to have a posttransplant outcome that was comparable to that of patients with standard criteria tumors.44 Post-interventional complete tumor necrosis with subsequent LT may even result in cancer cure.45 By using multiphasic contrast-enhanced CT and MRI, the European Association for the Study of the Liver criteria and the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors are current standard for assessing tumor response to LRTT.46 However, the use of tumor macromorphology in this context is controversial, since LRTT may lead to cancer devascularization and necrosis without accompanied tumor downsizing. Therefore, 18F-FDG-PET is increasingly studied for evaluating metabolic response to LRTT Most studies in this context were focusing on non-surgical palliative approaches. They consistently demonstrated that 18F-FDG-PET is an appropriate indicator of response to LRTT and postinterventional outcome.47–51 Only few trials have correlated 18F-FDG-PET data with histopathologic reports after liver resection or LT following LRTT (Table 1). Already in 1994, Torizuka et al. reported on the prognostic value of 18F-FDG-PET in 30 liver transplant patients with 32 HCC nodules following pre-LT neoadjuvant TACE.52 Based on visual PET evaluation, the authors have stratified according to the following FDG uptake pattern: Type A tumors showed increased FDG uptake (SUV ratio 1.07–2.66; n = 19); Type B tumors demonstrated similar FDG uptake than surrounding normal liver tissue (SUV ratio 0.77–1.04; n = 6); Type C tumors showed decreased or absent FDG uptake (SUV ratio 0.13–0.58; n = 9). On explant histopathology, viable tumor remained in all Type A and B tumors, whereas more than 90% necrosis was found in type C tumors. The authors concluded that PET might be useful to describe metabolic tumor behavior following TACE in the liver transplant setting.52 Cascales Campos et al. noted a decrease of the median SUV from pre-TACE 4 (range: 2.79–6.95) to 0 post-TACE (range: 0–4) in 6 liver transplant patients with HCC. On explant pathology, they found a tumor necrosis rate above 80% where SUV decreased to below 3.53 This interesting correlation could be confirmed in a follow-up trial of 20 liver transplant patients.54 In a study by Kornberg et al. including 93 liver transplant patients, PET-negativity was found to be the only independent clinical predictor of tumor response to LRTT (HR = 12.4; 95%CI 3.1–49.0; p < 0.001) assessed on explant pathology (≥50% tumor necrosis rate).55 Consequently, the authors concluded that 18F-FDG-PET is useful for selecting patients with advanced HCC that may benefit from LRTT and, thereby, from acceptable posttransplant prognosis.55

Table 1. 18F-FDG-PET for predicting tumor viability following LRTT in a neoadjuvant approach.

| Authors | Technique of LRTT | n | Stratification of subsets | Main study results |

| Torizuka et al.52 | TACE using iodized oil | 30 | Type A HCC: Increased FDG uptake (SUV 1.07–2.66) Type B HCC: Similar to surrounding liver tissue (SUV 0.77–1.04) Type C HCC: Decreased FDG uptake (SUV 0.13–0.58) |

Viable tumor following TACE in type A and B HCC; more than 90% necrosis in type C tumor; tumor necrosis rate <75% in SUV <0.6 and ≈ 100% in SUV >0.6. |

| Cascales Campos et al.53 | TACE | 6 | Post-TACE SUV < vs. ≥3 | Decrease of SUV to <3 post-TACE was associated with necrosis rate >80% on explant histopathology. |

| Cascales Campos et al.54 | TACE | 20 | Post-TACE SUV < vs. ≥3 | Decreases of SUV to <3 post-TACE was associated with necrosis rate >70% on explant histopathology and adequate 1- (100%) and 3-year (80%) survival post-LT. |

| Kornberg et al.55 | TACE and RFA | 59 | Increased vs. not increased 18F-FDG uptake (PET+ vs. PET− status) | PET− status was identified as the only independent clinical predictor (HR = 12.4; 95%CI 3.1–49.0; p < 0.001) of tumor response (≥50% tumor necrosis rate on explant pathology) to LRTT. |

| Kim et al.56 | TACE with lipiodol | 91 | Grade I: no 18F-FDG uptake or 18F-FDG uptake lower than in surrounding liver tissue Grade II: 18F-FDG uptake similar to the surrounding liver tissue Grade III: 18F-FDG uptake greater than in the surrounding liver tissue |

18F-FDG uptake correlated with histopathologic grade in treatment-naïve tumors but not in lipiodolized HCCs after TACE; 18F-FDG PET/CT showed a high diagnostic sensitivity and a moderate specificity in evaluating viability of lipiodolized HCC nodules. |

Abbreviations: 18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standard uptake value;TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Although the number of studies is still rather limited, there is an increasing body of evidence that 18F-FDG-PET provides valuable data for prognosis evaluation in the setting of LRTT. With special regard to LT, the switch from enhanced 18F-FDG-uptake pattern to PET-negativity following LRTT might probably indicate transplant eligibility. This, however, has to be assessed in prospective trials.

18F-FDG-PET for predicting outcome after liver resection for HCC

Hepatic resection in liver cancer may be performed with curative intention or in a neoadjuvant concept prior to LT. The major aim of a surgical bridging approach is tumor control in order to prevent cancer progression and patients’ drop-out from the waiting list. Besides, it allows for a precise assessment of biological tumor viability by histopathologic analysis of the resection specimen. After detection of aggressive tumor features, like MVI or poor grading, early preemptive LT may be recommended. In contrast, absence of unfavorable tumor features justifies a “wait and see” attitude with LT in case of recurrent tumor.57,58

In the past, several studies were able to demonstrate that enhanced 18F-FDG uptake on PET correlates with presence of aggressive histopathologic features assessed on resection specimen (Table 2).59–62 Other liver resection studies have focused on the prognostic role of 18F-FDG-PET with regard to recurrence-free and overall survival (Table 2).63–67 In 2 subsequent trials, the group by Hatano et al. demonstrated beneficial post-resectional outcome in patients with low tumor to non-tumor SUV ratio (TNR). Apart from that, TNR was even identified as a significant and independent predictor of postoperative recurrence (HR = 1.3; 95%CI 1.03–1.62; p = 0.03) and overall survival (HR = 1.6; 95%CI 1.07–2.38; p = 0.02), along with other well-known prognostic factors like AFP level and macroscopic portal vein invasion.64

Table 2. 18F-FDG-PET for predicting outcome after curative liver resection for HCC.

| Authors | n | Stratification of subsets | Major study results |

| Torizuka et al.59 | 17 | -------------------- | Pre-resection SUV was 6.89 ± 3.39 in low grade and 3.21 ± 0.58 in high grade tumors (p < 0.005). |

| Kobayashi et al.60 | 60 | High (≥3.2) vs. low (<3.2) SUVmax | Sensitivity and specificity of SUVmax ≥3.2 for predicting MVI were 77.8% and 74%. It increased to 88.9% and 82.4% by combining SUVmax with lens culinaris agglutinin a-reactive AFP. |

| Baek et al.61 | 54 | Low (<6.36) vs. high (≥6.36) TMR | TMR ratio on pre-resection 18F-FDG PET correlated with MVI (p = 0.005) and tumor differentiation (p = 0.002). TMR ≥6.36 almost reached statistical significance in multivariate analysis for predicting HCC relapse (p = 0.061). |

| Ochi et al.62 | 89 | High (≥8.8) vs. low (<8.8) SUVmax | SUVmax correlated significantly with tumor distance to microsatellite lesion pattern (R = 0.57; p < 0.0001). SUVmax was identified as an independent predictor of microsatellite distance >1 cm (HR = 1.60; 95%CI:1.23–2.26; p = 0.002) and extrahepatic HCC recurrence (HR = 1.24; 95%CI 1.01–1.55; p = 0.033). |

| Hatano et al.63 | 31 | High (>2) vs. low (<2) SUV ratio | Overall 5-year survival rate was 63% in the high and 29% in the low SUV ratio subsets (p = 0.006). SUV ratio correlated significantly with tumor-related mortality (p = 0.001), tumor number (p = 0.002), tumor size (p = 0.001), vascular invasion (p = 0.005) and capsule invasion (p = 0.001). It did not remain as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in multivariable analysis. |

| Seo et al.64 | 70 | Low (<5) vs. high (≥5) SUV Low (<2) vs. high (≥2) TNR |

Overall and recurrence-survival rates were significantly lower in the high than in the low FDG uptake groups (p = 0.002; p = 0.0005 for SUV; p = 0.001; p = 0.0002 for TNR). TNR but not SUV was identified as an independent predictor of postoperative recurrence (HR = 1.3; 95%CI 1.03–1.62; p = 0.03) and overall survival (HR = 1.6; 95%CI 1.07–2.38; p = 0.02). |

| Han et al.65 | 298 | Low (<3.5) vs. high (>3.5) SUV | Preoperative SUV >3.5 was identified as an independent predictor of high grade tumor (HR = 3.305; 95%CI: 1.214–8.996; p = 0.019), tumor recurrence (HR = 2.025; 95%CI: 1.046–3.921; p = 0.036), and overall survival (HR = 7.331; 95%CI: 2.182–24.630; p = 0.001). |

| Ahn et al.66 | 93 | Low (<4) vs. high (≥4) SUVmax Low (<2) vs. high (≥2) TNR |

SUVmax and TNR correlated significantly (p < 0.001) with poor tumor differentiation. SUVmax ≥4 and TNR ≥2 were significant predictors for early recurrence-free survival (p = 0.026; p = 0.015) and overall survival (p = 0.005; p = 0.013). However, PET was no independent prognostic factor. |

| Kitamura et al.67 | 63 | Low (<2) vs. high (≥2) TNR | TNR ≥2 was identified as an independent predictor for time interval to HCC recurrence. It was significantly lower in patients with recurrence beyond 1 year (4.4 ± 1.6; p < 0.05) or no recurrence (3.8 ± 1.5; p < 0.01) compared to those with early (within 1 year) tumor relapse (8.4 ± 6.3). Apart from that, TNR was identified as an independent prognostic factor for recurrence patterns according to the MC. It was significantly lower in patients developing tumor relapse within the MC (1.9 ± 1.6; p < 0.05) or no recurrence (1.3 ± 0.5; p < 0.01) compared to patients with tumor recurrence exceeding the MC (2.9 ± 2.6). |

Abbreviations: 18F-FDG, 18F-fludeoxyglucose; CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HR, hazard ratio; MC, Milan criteria; MVI, microvascular invasion; PET, positron emission tomography; SUV, standard uptake value; TMR, tumor-to-muscle ratio; TNR, tumor-to-nontumor uptake ratio.

In a subset of 298 HCC patients following liver resection, Han et al. identified preoperative SUV >3.5 as an independent predictor of high grade tumor (HR = 3.305; 95%CI: 1.214–8.996; p = 0.019), tumor recurrence (HR = 2.025; 95%CI 1.046–3.921; p = 0.036), and overall survival (HR = 7.331; 95%CI 2.182–24.630; p = 0.001).65

Analyzing 93 HCC patients, Ahn et al. demonstrated SUVmax ≥4 and TNR ≥2 to be significant predictors for both early recurrence-free survival (within 1 year from liver resection; p = 0.026; p = 0.015) and overall survival (p = 0.005; p = 0.013). However, FDG uptake had not enough prognostic power for remaining as an independent predictive factor on multivariate analysis.66

Kitamura and colleagues were able to demonstrate that TNR ≥2 is an independent predictor for time interval to HCC recurrence (within 1 year vs. beyond 1 year or no recurrence).67 TNR was significantly lower in patients with either recurrence beyond 1 year (4.4 ± 1.6; p < 0.05) or no recurrence (3.8 ± 1.5; p < 0.01) compared to those with early (within 1 year) tumor relapse (8.4 ± 6.3). Apart from that, TNR was identified as an independent prognostic factor for recurrence patterns according to the MC. It was significantly lower in patients developing tumor relapse meeting the MC (1.9 ± 1.6; p < 0.05) or no recurrence (1.3 ± 0.5; p < 0.01), compared to patients suffering from tumor recurrence exceeding the MC (2.9 ± 2.6). The authors finally concluded that 18F-FDG-PET may be useful for establishing an individualized treatment strategy. They proposed primary liver resection in patients with TNR <2 (low risk of early and extended HCC recurrence), but LT or adjuvant treatment in those with TNR ≥2 (high risk of early or extended HCC recurrence after hepatic resection).67

According to the presented data, there seems to be enough evidence that 18F-FDG-PET correlates with tumor biology and outcome in HCC patients following liver resection. In the context of LT, these data may have important clinical implications for applying FDG-PET in an individual decision making process on liver resection for pretransplant bridging.

18F-FDG PET for predicting outcome after liver transplantation

Correlation with unfavorable histopathologic features

Poor tumor differentiation and MVI are highly relevant prognostic features in LT for HCC.10,22 In order to select suitable liver transplant patients with advanced HCC but favorable biology, Cillo et al. have implemented preoperative tumor biopsy decision making.68 However, such a diagnostic approach may not generally be recommended due to heterogenic tumor aggressiveness and risk of tumor cell spread.25,26,69 As shown in Table 3, 18F-FDG-PET is able to non-invasively indicate presence of MV and poor differentiation. We found a wide range of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). In contrast, accuracy rates were rather high in all available studies, ranging from 51.3% to 71.4% for poor grading, and from 63.3% to 88.1% for MVI, respectively. These findings clearly implicate that radiographic results should be augmented by 18F-FDG-PET data for improving pre-LT assessment of biological tumor aggressiveness.

Table 3. 18F-FDG-PET for predicting aggressive histopathologic features in liver transplant patients with HCC.

| Authors | n | PET−/PET+ (n) | Predicting poor grading (Sensitivity/Specificity/PPV/NPV/Accuracy) | Predicting MVI (Sensitivity/Specificity/PPV/NPV/Accuracy) |

| Yang et al.70 | 38 | 25/13 | 47.8%/85.7%/84.6%/50%/60.5% | 77.8%/79.3%/53.8%/92%/78.9% |

| Kornberg et al.72 | 42 | 26/16 | 83.3%/69.4%/31.3%/96.1%/71.4% | 82.3%/92%/87.5%/88.5%/88.1% |

| Kornberg et al.73 | 91 | 36/19 | 76.4%/70.3%/37.1%/92.9%/71.4% | 81.1%/90.7%/85.7%/87.5%/86.8% |

| Lee et al.75 | 191 | 136/55 | 37.3%/81.7%/75.5%/46%/51.3% | 45.4%/83.9%/66%/69.1%/67.5% |

| Lee et al.76 | 280 | 190/90 | (beyond MC) 52.6%/62.3%/61.2%/53.8%/57.1% |

(beyond MC) 58.4%/68.6%/67.2%/60%/63.3% |

| Hsu et al.78 | 147 | 117/30 | 100%/80.7%/6.7%/100%/81% | 30.3%/85.7%/56.7%/66.7%/64.6% |

Abbreviations: MC, Milan criteria; NPV, negative predictive value; PET, positron emission tomography; PPV, positive predictive value.

Predicting posttransplant outcome

In recent years, there is an increasing number of studies that were focusing on the predictive value of FDG-PET in the liver transplant setting (Table 4). In 2006, Yang et al. from South Korea were the first to correlate preoperative 18F-FDG-PET with outcome in 38 HCC patients following LT.70 In this study, positive PET-status (18F-FDG uptake in the tumor greater than in surrounding normal liver tissue) correlated significantly with markers of biological tumor activity, such as AFP-level (p < 0.001) and vascular invasion (p = 0.003). Posttransplant HCC recurrence rate was 61.5% in 18F-FDG-avid, but only 12% in non-18F-FDG-avid patients (p = 0.003). The 2-year recurrence-free survival rates were 85.1% and 46.1% in patients with PET− and PET+ tumors, respectively (p = 0.0005). In the Milan In subset (n = 26), none of 20 PET-negative (0%) but 4 of 6 PET-positive patients (66.7%) developed tumor relapse. In contrast, tumor recurrence rates did not differ between PET− (60%) and PET+ (60%) patients when exceeding the Milan criteria.70 The same group reported in 2009 on 59 HCC patients that underwent 18F-FDG-PET prior to LDLT (n = 57) or deceased donor (n = 2) LT.71 In multivariate analysis, only tumor SUVmax (TSUVmax)/normal liver SUVmax (LSUVmax) ≥1.15 (p = 0.001) and vascular invasion (p = 0.014) were identified as significant and independent predictors of tumor recurrence. The authors critically noted that the significance of the data might be limited by a high rate of preoperative LRTT (75%) and, thereby, altered tumor biology.71

Table 4. 18F-FDG-PET for predicting outcome after liver transplantation for HCC.

| Authors | n | n (PET−/PET+) | Overall outcome (PET−/PET+) | Outcome beyond standard criteria (PET−/PET+) |

| Yang et al.70 | 38 | 25/13 | Overall 2y RFS: 85.1%/46.1% | RR beyond Milan: 60%/57% |

| Lee et al.71 | 59 | 38/21 | Overall 2y RFS: 97%/42% | RR beyond Milan: 9%/67% |

| Kornberg et al.72 | 42 | 26/16 | Overall 3y RFS: 93%/35% | RR beyond Milan: 11.1%/53.8% |

| Kornberg et al.73 | 55 | 36/19 | Overall 3y RFS: 93.3%/46.9% | 3y RFS beyond Milan: 80%/44% |

| Kornberg et al.74 | 91 | 56/35 | Overall RR: 3.6%/54.3% | 5y RFS beyond Milan: 81%/21% 5y RFS beyond UCSF: 85.7%/19.2% |

| Lee et al.75 | 191 | 136/55 | 3y RFS: 86.8%/57.1% | – |

| Lee et al.76 | 280 | 190/90 | 5y RFS within Milan: 92.3%/76.3% 5y RFS within UCSF: 91.9%/81.8% |

5y RFS beyond Milan: 73.3%/37.5% 5y RFS beyond UCSF: 72.8%/30.7% |

| Lee et al.77 | 280 |

NCCK–In/NCCK-Out 164/116 |

NCCK–In/NCCK-Out 5y RFS (clin. staging): 80.7%/45.1% 5y RFS (path. staging): 84%/44.4% 5y OS (clin. staging): 83.6%/59.8% 5y OS (path. staging): 85.2%/60.2% |

NCCK–In/NCCK Out + Milan In/beyond NCCK and Milan 5y RFS (clin. staging): 80.7%/75.5%/30.8% 5y RFS (path. staging): 84%/81%/30.8% 5y OS (clin. staging): 83.6%/73.5%/53.9% 5y OS (path. staging): 85.2%/73.8%/57.6% |

| Hsu et al.78 | 147 | 117/30 | Overall 5y RFS: 84.8%/68.3% |

Risk stratification based on PET and UCSF (low-risk/intermediate risk/high risk) 5y RFS (clin. staging): 85.5%/83.9%/29.6% 5y RFS (path. staging): 94.0%/75.8%/29.6% |

| Hong et al.79 | 123 | 87/36 | Overall 5y RFS: 93.4%/49.1% |

Risk stratification based on PET and AFP level (low risk/intermediate risk/high risk) Overall 5y RFS: 93.6%/77.7%/8.3% 5y RFS within Milan: 92.6%/73.9%/16.7% 5y RFS beyond Milan: 100%/100%/0% |

| Takade et al.80 | 182 | 139/43 | Overall RR: 12%/28% |

Risk stratification based on Milan, AFP and PET (Milan In or Milan Out + AFP <115ng/ml + PET−/Others) 5y OS: 75%/44% |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; NCCK, National Cancer Center Korea; OS, overall survival; PET, positron emission tomography; RFS, recurrence-free survival; RR, recurrence rate; UCSF, University of California San Francisco.

Kornberg et al. have specifically assessed the predictive value of pretransplant 18F-FDG-PET for presence of MVI.72 PET-positivity was found as the only independent clinical predictor of MVI (HR = 14.4; 95%CI 0.003–0.126; p = 0.001) in 46 liver transplant patients. Positive and negative predictive values of enhanced 18F-FDG uptake on pretransplant PET were 87.5% and 88.5%. Eight of 16 PET+ patients developed HCC recurrence (50%) but only 1 of 26 PET− patients (3.8%; p < 0.001). In the Milan In subset, none of 17 PET-negative (0%) but 1 of 3 PET+ patients (33.3%) demonstrated tumor relapse (p = 0.004). In the Milan Out subgroup, tumor recurrence rates were 11.1% and 53.8% in non-18F-FDG-avid and 18F-FDG-avid HCCs, respectively (p = 0.004). The authors concluded that pretransplant 18F-FDG-PET is a useful and reliable predictor of MVI and post-LT tumor recurrence. The lack of repeat 18F-FDG-PET after neoadjuvant LRTT was recognized as a major limitation of this trial.72 In a follow-up trial including 55 liver transplant patients, the authors reported on a relative risk of 9.5 and 6.4 for 18F-FDG-avid patients to reveal poor grading and MVI. In multivariate analysis, only poor differentiation (HR = 44; 95%CI 4.248–455.774; p = 0.002) and PET+ status (HR = 23.9; 95%CI 2.143–268.588; p = 0.01) were identified as independent promoters of tumor recurrence.73

The same group focused in 2011 on the prognostic importance of 18F-FDG-PET in advanced HCC stages (Table 4).74 In a series of 91 liver transplant patients, the authors were able to demonstrate that patients with PET-negative tumors exceeding the MC or UCSF criteria had a comparable outcome to patients meeting standard criteria. In multivariate analysis, PET status was identified as the strongest clinical predictor of recurrence-free survival (Odds ratio = 21.6; 95%CI 4.9–94.9; p < 0.001). In addition, the authors identified PET-positivity as an independent clinical predictor of patients’ drop out from the waiting list due to tumor progression (HR = 5.5; 95%CI 1.5–22.2; p = 0.01). They suggested that patients with 18F-FDG-avid HCC on the waiting list should undergo aggressive LRTT and close re-evaluations in order to prevent their drop-out due to tumor progression.74

Lee et al. were the first to describe a specific association of metabolic behavior of HCC on 18F-FDG PET/CT with risk of early posttransplant tumor recurrence.75 In a series of 191 patients following LDLT, 20 patients suffered from early (within 6 months) and 18 patients from late (beyond 6 months) tumor relapse, whereas 153 patients remained tumor-free. Overall 3-year survival rate was 0% in patients with early HCC recurrence, compared to 64% and 94% in those with late or no tumor relapse (p < 0.001), respectively. In multivariate analysis, only PET+ status was identified as an independent predictor of early tumor recurrence (HR 8.472; 95%CI 3.077–23.325; p < 0.001), whereas PET-positivity did not correlate with late HCC recurrence. The authors, therefore, concluded that early and late tumor relapse reveal different biological aggressiveness, which may be reflected by 18F-FDG uptake pattern on PET.75

In recent years, studies have increasingly focused on the prognostic significance of hybrid selection criteria combining 18F-FDG uptake with morphometric data. In 2015, Lee et al. reported on the so-far largest series in this context, including 280 HCC patients following LDLT.76 Apart from total tumor size (TTS >10 cm) and MVI, PET-positivity was identified as most significant independent prognostic factor in the Milan Out subset (HR = 3.803; 95%CI 1.876–7.707; p < 0.001). Consequently, the authors have stratified their data according to PET findings and TTS, since both features were available prior to LT. In PET-negative Milan Out patients with TTS <10 cm (n = 55), 5-year overall and recurrence-free survival rates were not significantly different (73.4%; 80.4%) from Milan In patients (87.2%; 89.9%), but significantly better than in PET-positive beyond Milan patients exceeding 10 cm in TTS (59.7%; 42.8%; p < 0.001). By combining 18F-FDG-PET with TTS, 37.4% of patients beyond the MC were identified as eligible liver transplant candidates in this series.76 The prognostic power of this novel expanded HCC criteria set (“The National Cancer Center Korea criteria”; NCCK criteria) in comparison to other established selection approaches has been evaluated by the same transplant group.77 Enrolling 280 patients following LDLT, 164 of them fulfilled the NCCK criteria (PET-negative + TTS <10 cm) and 132 met the MC. Based on both preoperative and histopathologic staging, 5-year recurrence-free survival rates were significantly higher in patients fulfilling the NCCK criteria (80.7%; 84%) compared to those exceeding them (45.1%; 44.7%; p < 0.001). Comparably, tumor-specific outcome was not different when stratified according to the MC (Milan In: 82%; 84.4%; Milan Out: 46.9%; 52.7%; p < 0.001). However, the NCCK revealed a higher accuracy of predicting explant pathology by preoperative imaging than the MC (95% vs. 78.9%; Cohen’s Kappa 0.850 vs. 0.583).77

Recently, Hsu et al. proposed an expanded HCC selection approach that was based on 18F-FDG uptake and UCSF criteria.78 The authors distinguished between high (TNR ≥2; n = 9), low (TNR <2, n = 21) and no FDG uptake (n = 117) subgroups. The 5-year recurrence-free survival was significantly worse in the high (29.6%) than in the low (85%; p = 0.005) and the no FDG uptake subsets (85%; p < 0.001). In contrast, tumor-specific outcome did not differ between low and negative FGD-uptake patients (p = 0.337). Based on PET and pathological UCSF data, the following risk groups were defined: Low-risk: UCSF In + negative FDG-PET; intermediate-risk: beyond UCSF + FDG-negative or FDG-positive with TNR <2; high-risk: FDG-uptake ≥2. Recurrence-free survival rates at 5 years post-LT were 94% in the low-risk group, 75.8% in the intermediate-risk group (p = 0.013 vs. low-risk) and 29.6% in the high risk subset (p < 0.001 vs. low- and intermediate-risk patients). In multivariable analysis, only high risk status based on pathological staging remained as a significant and independent promoter of HCC recurrence (HR = 24.15; 95%CI 5.76–101.23; p < 0.001). Discrepant results between clinical and pathological tumor staging and the small sample size in the high-risk subgroup (n = 9) were recognized as study limitations.78

Other transplant groups recently suggested that combining 18F-FDG-PET with AFP level may significantly improve pre-LT selection process. Hong et al. reported on a series of 123 patients that underwent 18F-FDG-PET prior to LDLT.79 Only pre-LT available tumor factors were included in this analysis. In multivariable investigation, only PET-positivity (HR = 9.766; 95%CI 3.557–26.861; p < 0.001) and serum AFP level ≥200 ng/ml (HR = 6.234; 95%CI 2.643–14.707; p < 0.001) were identified as independent prognostic factors of HCC relapse. Accordingly, the authors defined the following risk constellations: low risk: AFP <200 ng/ml + PET− status; intermediate risk: AFP ≥200 ng/ml + PET− or AFP <200 ng/ml + PET-positive; high risk: AFP ≥200 ng/ml + PET-positive. Five-year recurrence-free survival rates were 93.6% in the low-risk group (n = 75), 77.7% in the intermediate-risk group (n = 36,) but only 8.3% in the high-risk subset (n = 12; p < 0.001).79 They proposed that the MC should be completely replaced by a biology-guided selection approach.

The prognostic value of combining 18F-FDG-PET with AFP was just recently confirmed by a Japanese multicenter study including 182 HCC patients.80 Apart from Milan Out status, which was the strongest prognostic factor (p < 0.001), only AFP level ≥115 ng/ml (relative risk = 3.077; 95%CI 1.748–7.023; p = 0.008) and PET-positivity (RR = 2.554; 95%CI 1.101–5.924; p = 0.029) were identified as independent promoters of HCC relapse. The following risk groups were defined: group A: meeting the MC (n = 133); group B: beyond MC + AFP level <115 ng/ml + PET− status (n = 22); group C: beyond MC + AFP level ≥115 ng/ml and/or PET+ status (n = 27). Tumor recurrence-rates at 5 years post-LT were comparable between group A and group B (6% vs. 19%; p = 0.176) but significantly higher in group C (53%; p < 0.001 vs. group A; p = 0.012 vs. group B). Based on these findings, the authors defined as novel expanded selection criteria: within the MC or beyond MC + AFP level <115 ng/ml + negative PET-status. The 5-year recurrence-free survival rates were 75% and 44% in patients meeting and exceeding them (p = 0.003). In addition, its correlation with poor grading and MVI was higher in comparison to previously established HCC transplant criteria (MC, UCSF, UTS; Kyoto, modified Tokyo).

Conclusions

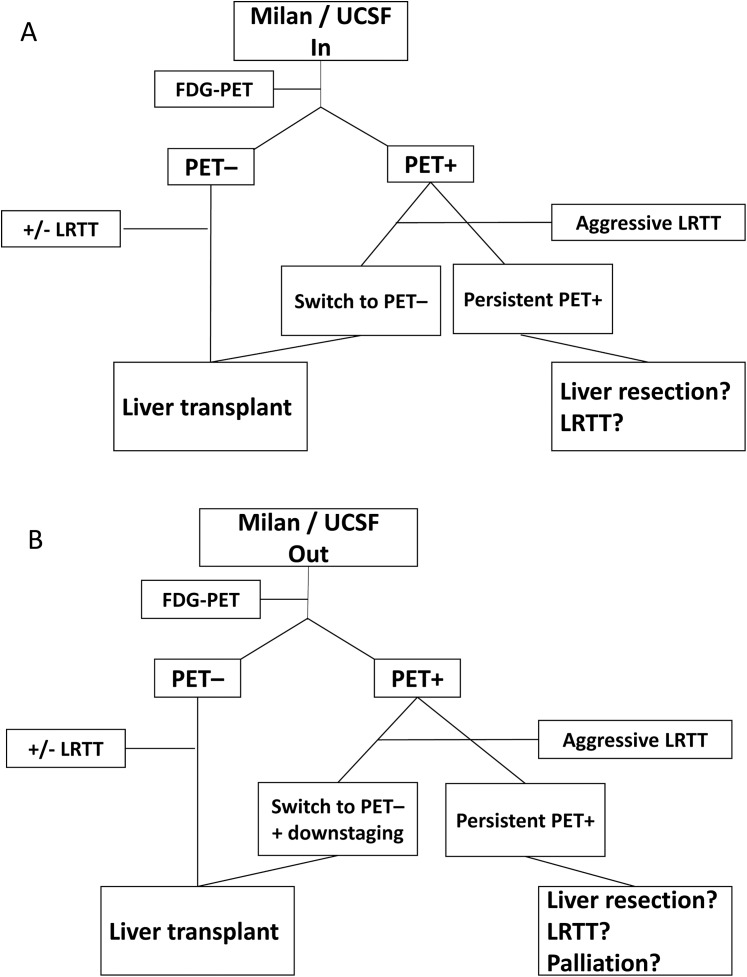

Current available studies addressing the prognostic role of 18F-FDG-PET in liver transplant patients with HCC have several limitations. First, they were of retrospective character and included a relatively small number of patients. Second, most of them have included patients after LDLT and the results may not directly be transferred to recipients of a deceased donor liver allograft. Third, study populations were rather heterogeneous with regard to listing and removal criteria, pretransplant waiting times and applied LRTT concepts. And furthermore, there were significant differences in qualitative and quantitative 18F-FDG uptake measurements. However, as shown in this review, pretransplant 18F-FDG-PET provides very useful information on biological tumor viability and posttransplant outcome. Despite the lack of prospective clinical trials, there seems to be enough evidence that 18F-FDG-PET may identify suitable liver transplant patients with advanced tumor stages but less aggressive behavior. By strictly adhering to established standards of macromorphology-based liver allocation, these patients are currently excluded from LT and, thereby, from a major opportunity of cure. Based on the presented data, we suggest a simplified selection algorithm combining morphometric features with 18F-FDG-PET for improving outcome in patients meeting (Fig. 1A) and exceeding (Fig. 1B) standard criteria. Although these selection approaches have to be validated by future studies, our review clearly suggests that 18F-FDG-PET should be implemented in pretransplant decision-making for safely expanding the acceptable tumor burden limits and the pool of suitable liver transplant patients with HCC.

Fig. 1. Selection algorithm using 18F-FDG-PET in HCC patients meeting morphometric standard criteria (A) or exceeding morphometric standard criteria (B).

Abbreviations

- 18F-FDG

18F-fludeoxyglucose

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computed tomography

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR

hazard ratio

- LDLT

living donor liver transplantation

- LRTT

locoregional tumor treatment

- LSUVmax

normal liver maximum standard uptake value

- LSUVmean

liver mean standard uptake value

- LT

liver transplantation

- MC

Milan criteria

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MVI

microvascular invasion

- NCCK

National Cancer Center Korea

- NPV

negative predictive value

- OS

overall survival

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PPV

positive predictive value

- RFS

recurrence-free survival

- RR

recurrence rate

- SUV

standard uptake value

- TACE

transarterial chemotherapy

- TLR

tumor-to-normal liver uptake ratio

- TMR

tumor-to-muscle ratio

- TNR

tumor-to-nontumor uptake ratio

- TSUVmax

tumor maximum standard uptake value

- TTS

total tumor size

- UCSF

University of California San Francisco

- UTS

Up-to-seven

References

- 1.Schütte K, Balbisi F, Malfertheiner P. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastrointest Tumors. 2016;3:37–43. doi: 10.1159/000446680. doi:10.1159/000446680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosetti C, Turati F, La Vecchia C. Hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:753–770. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.08.007. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pang TC, Lam VW. Surgical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:245–252. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i2.245. doi:10.4254/wjh.v7.i2.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonseca AL, Cha CH. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a comprehensive overview of surgical therapy. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:712–719. doi: 10.1002/jso.23673. doi:10.1002/jso.23673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawada T, Kubota K. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2007;24:126–130. doi: 10.1159/000101900. doi:10.1159/000101900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ringe B, Pichlmayr R, Wittekind C, Tusch G. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: experience with liver resection and transplantation in 198 patients. World J Surg. 1991;15:270–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01659064. doi:10.1007/BF01659064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE, Sheahan DG, Yokoyama I, Demetris AJ, Todo S, et al. Hepatic resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1991;214:221–228. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199109000-00005. discussion 228–229. doi:10.1097/00000658-199109000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Role of liver transplantation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Surg Oncol. 1993;9:337–340. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980090411. doi:10.1002/ssu.2980090411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. doi:10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Earl TM, Chapman WC. Transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: the North American experience. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2013;190:145–164. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-16037-0_10. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16037-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maggs JR, Suddle AR, Aluvihare V, Heneghan MA. Systematic review: the role of liver transplantation in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1113–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05072.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrero JI, Sangro B, Pardo F, Quiroga J, Iñarrairaegui M, Rotellar F, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma across Milan criteria. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:272–278. doi: 10.1002/lt.21368. doi:10.1002/lt.21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazzaferro V, Bhoori S, Sposito C, Bongini M, Langer M, Miceli R, et al. Milan criteria in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an evidence-based analysis of 15 years of experience. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(Suppl 2):S44–S57. doi: 10.1002/lt.22365. doi:10.1002/lt.22365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma P, Balan V, Hernandez JL, Harper AM, Edwards EB, Rodriguez-Luna H, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: the MELD impact. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:36–41. doi: 10.1002/lt.20012. doi:10.1002/lt.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler M, De Pauw F, Vereerstraeten P, Fancello A, Lerut J, Starkel P, et al. Outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma listed for liver transplantation within the Eurotransplant allocation system. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:526–533. doi: 10.1002/lt.21399. doi:10.1002/lt.21399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elshamy M, Aucejo F, Menon KV, Eghtesad B. Hepatocellular carcinoma beyond Milan criteria: Management and transplant selection criteria. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:874–880. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v8.i21.874. doi:10.4254/wjh.v8.i21.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sotiropoulos GC, Malagó M, Molmenti E, Paul A, Nadalin S, Brokalaki E, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: is clinical tumor classification before transplantation realistic? Transplantation. 2005;79:483–487. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000152801.82734.74. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000152801.82734.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah SA, Tan JC, McGilvray ID, Cattral MS, Cleary SP, Levy GA, et al. Accuracy of staging as a predictor for recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation. 2006;81:1633–1639. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000226069.66819.7e. doi:10.1097/01.tp.0000226069.66819.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394–1403. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24563. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70284-5. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volk ML, Vijan S, Marrero JA. A novel model measuring the harm of transplanting hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding Milan criteria. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:839–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02138.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cillo U, Giuliani T, Polacco M, Herrero Manley LM, Crivellari G, Vitale A. Prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma biological behavior in patient selection for liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:232–252. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.232. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaido T. Selection criteria and current issues in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2016;5:121–127. doi: 10.1159/000367749. doi:10.1159/000367749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grąt M, Stypułkowski J, Patkowski W, Bik E, Krasnodębski M, Wronka KM, et al. Limitations of predicting microvascular invasion in patients with hepatocellular cancer prior to liver transplantation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39881. doi: 10.1038/srep39881. doi:10.1038/srep39881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, Nagorney DM, Ng IO, Ikai I, et al. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: Implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1086–1092. doi: 10.1002/lt.20472. doi:10.1002/lt.20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawlik TM, Gleisner AL, Anders RA, Assumpcao L, Maley W, Choti MA. Preoperative assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma tumor grade using needle biopsy: implications for transplant eligibility. Ann Surg. 2007;245:435–442. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250420.73854.ad. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000250420.73854.ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowe LR, Mulvihill SJ, Emerson L, Gopez EV. Subcutaneous tumor seeding following needle core biopsy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35:717–721. doi: 10.1002/dc.20717. doi:10.1002/dc.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumaran V. Role of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:S97–S103. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2014.01.002. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofman MS, Hicks RJ. How we read oncologic FDG PET/CT. Cancer Imaging. 2016;16:35. doi: 10.1186/s40644-016-0091-3. doi:10.1186/s40644-016-0091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajo M, Kajiya Y, Jinguji M, Nakabeppu Y, Nakajo M, Nihara T, et al. Current clinical status of 18F-FLT PET or PET/CT in digestive and abdominal organ oncology. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:951–961. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0947-9. doi:10.1007/s00261-016-0947-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho Y, Lee DH, Lee YB, Lee M, Yoo JJ, Choi WM, et al. Does 18F-FDG positron emission tomography-computed tomography have a role in initial staging of hepatocellular carcinoma? PLoS One. 2014;9:e105679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0105679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwata Y, Shiomi S, Sasaki N, Jomura H, Nishiguchi S, Seki S, et al. Clinical usefulness of positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in the diagnosis of liver tumors. Ann Nucl Med. 2000;14:121–126. doi: 10.1007/BF02988591. doi:10.1007/BF02988591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiomi S, Kawabe J. Clinical applications of positron emission tomography in hepatic tumors. Hepatol Res. 2011;41:611–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00819.x. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034X.2011.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trojan J, Schroeder O, Raedle J, Baum RP, Herrmann G, Jacobi V, et al. Fluorine-18 FDG positron emission tomography for imaging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3314–3319. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01544.x. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawamura E, Shiomi S, Kotani K, Kawabe J, Hagihara A, Fujii H, et al. Positioning of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography imaging in the management algorithm of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1722–1727. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12611. doi:10.1111/jgh.12611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon KT, Kim JK, Kim DY, Ahn SH, Lee JD, Yun M, et al. Role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in detecting extrahepatic metastasis in pretreatment staging of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2007;72(Suppl 1):104–110. doi: 10.1159/000111715. doi:10.1159/000111715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Na SJ, Oh JK, Hyun SH, Lee JW, Hong IK, Song BI, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT Can Predict Survival of Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:730–736. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.182022. doi:10.2967/jnumed.116.182022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiomi S, Nishiguchi S, Ishizu H, Iwata Y, Sasaki N, Tamori A, et al. Usefulness of positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose for predicting outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1877–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03888.x. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JD, Yun M, Lee JM, Choi Y, Choi YH, Kim JS, et al. Analysis of gene expression profiles of hepatocellular carcinomas with regard to 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake pattern on positron emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:1621–1630. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1602-1. doi:10.1007/s00259-004-1602-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun DW, An L, Wei F, Mu L, Shi XJ, Wang CL, et al. Prognostic significance of parameters from pretreatment (18)F-FDG PET in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016;41:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00261-015-0603-9. doi:10.1007/s00261-015-0603-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JW, Kim JH, Kim SK, Kang KW, Park KW, Choi JI, et al. A prospective evaluation of 18F-FDG and 11C-acetate PET/CT for detection of primary and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1912–1921. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055087. doi:10.2967/jnumed.108.055087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheung TT, Ho CL, Lo CM, Chen S, Chan SC, Chok KS, et al. 11C-acetate and 18F-FDG PET/CT for clinical staging and selection of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma for liver transplantation on the basis of Milan criteria: surgeon’s perspective. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:192–200. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.107516. doi:10.2967/jnumed.112.107516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bharat A, Brown DB, Crippin JS, Gould JE, Lowell JA, Shenoy S, et al. Pre-liver transplantation locoregional adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma as a strategy to improve longterm survival. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.06.016. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otto G, Herber S, Heise M, Lohse AW, Mönch C, Bittinger F, et al. Response to transarterial chemoembolization as a biological selection criterion for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1260–1267. doi: 10.1002/lt.20837. doi:10.1002/lt.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agopian VG, Morshedi MM, McWilliams J, Harlander-Locke MP, Markovic D, Zarrinpar A, et al. Complete pathologic response to pretransplant locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma defines cancer cure after liver transplantation: analysis of 501 consecutively treated patients. Ann Surg. 2015;262:536–545. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001384. discussion 543–545. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hussain HK, Barr DC, Wald C. Imaging techniques for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and the evaluation of response to treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2014;34:398–414. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1394140. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1394140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song MJ, Bae SH, Yoo IeR, Park CH, Jang JW, Chun HJ, et al. Predictive value of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT for transarterial chemolipiodolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3215–3222. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i25.3215. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i25.3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song MJ, Bae SH, Lee SW, Song DS, Kim HY, Yoo IeR, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT predicts tumour progression after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:865–873. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2366-2. doi:10.1007/s00259-013-2366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JW, Oh JK, Chung YA, Na SJ, Hyun SH, Hong IK, et al. Prognostic significance of 18F-FDG uptake in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization or concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:509–516. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.167338. doi:10.2967/jnumed.115.167338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma W, Jia J, Wang S, Bai W, Yi J, Bai M, et al. The prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT for hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) Theranostics. 2014;4:736–744. doi: 10.7150/thno.8725. doi:10.7150/thno.8725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho E, Jun CH, Kim BS, Son DJ, Choi WS, Choi SK. 18F-FDG PET CT as a prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2015;26:344–350. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2015.0152. doi:10.5152/tjg.2015.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torizuka T, Tamaki N, Inokuma T, Magata Y, Yonekura Y, Tanaka A, et al. Value of fluorine-18-FDG-PET to monitor hepatocellular carcinoma after interventional therapy. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1965–1969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cascales Campos P, Ramirez P, Gonzalez R, Febrero B, Pons JA, Miras M, et al. Value of 18-FDG-positron emission tomography/computed tomography before and after transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing liver transplantation: initial results. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:2213–2215. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.05.023. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cascales-Campos PA, Ramírez P, Lopez V, Gonzalez R, Saenz-Mateos L, Llacer E, et al. Prognostic value of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography after transarterial chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:2374–2376. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.08.026. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kornberg A, Witt U, Matevossian E, Küpper B, Assfalg V, Drzezga A, et al. Extended postinterventional tumor necrosis-implication for outcome in liver transplant patients with advanced HCC. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53960. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053960. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim HO, Kim JS, Shin YM, Ryu JS, Lee YS, Lee SG. Evaluation of metabolic characteristics and viability of lipiodolized hepatocellular carcinomas using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1849–1856. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079244. doi:10.2967/jnumed.110.079244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhangui P, Allard MA, Vibert E, Cherqui D, Pelletier G, Cunha AS, et al. Salvage versus primary liver transplantation for early hepatocellular carcinoma: do both strategies yield similar outcomes? Ann Surg. 2016;264:155–163. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001442. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamashita Y, Yoshida Y, Kurihara T, Itoh S, Harimoto N, Ikegami T, et al. Surgical results for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after curative hepatectomy: Repeat hepatectomy versus salvage living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:961–968. doi: 10.1002/lt.24111. doi:10.1002/lt.24111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torizuka T, Tamaki N, Inokuma T, Magata Y, Sasayama S, Yonekura Y, et al. In vivo assessment of glucose metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma with FDG-PET. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1811–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kobayashi T, Aikata H, Honda F, Nakano N, Nakamura Y, Hatooka M, et al. Preoperative fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for prediction of microvascular invasion in small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2016;40:524–530. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000405. doi:10.1097/RCT.0000000000000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baek YH, Lee SW, Jeong YJ, Jeong JS, Roh YH, Han SY. Tumor-to-muscle ratio of 8F-FDG PET for predicting histologic features and recurrence of HCC. Hepatogastroenterology. 2015;62:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ochi H, Hirooka M, Hiraoka A, Koizumi Y, Abe M, Sogabe I, et al. 18F-FDG-PET/CT predicts the distribution of microsatellite lesions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:798–804. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.328. doi:10.3892/mco.2014.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hatano E, Ikai I, Higashi T, Teramukai S, Torizuka T, Saga T, et al. Preoperative positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose is predictive of prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. World J Surg. 2006;30:1736–1741. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0791-5. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0791-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seo S, Hatano E, Higashi T, Hara T, Tada M, Tamaki N, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts tumor differentiation, P-glycoprotein expression, and outcome after resection in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:427–433. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1357. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han JH, Kim DG, Na GH, Kim EY, Lee SH, Hong TH, et al. Evaluation of prognostic factors on recurrence after curative resections for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17132–17140. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17132. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahn SG, Kim SH, Jeon TJ, Cho HJ, Choi SB, Yun MJ, et al. The role of preoperative [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in predicting early recurrence after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinomas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2044–2052. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1660-1. doi:10.1007/s11605-011-1660-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kitamura K, Hatano E, Higashi T, Seo S, Nakamoto Y, Yamanaka K, et al. Preoperative FDG-PET predicts recurrence patterns in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:156–162. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1990-y. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1990-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cillo U, Vitale A, Grigoletto F, Gringeri E, D’Amico F, Valmasoni M, et al. Intention-to-treat analysis of liver transplantation in selected, aggressively treated HCC patients exceeding the Milan criteria. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:972–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01719.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seehofer D, Öllinger R, Denecke T, Schmelzle M, Andreou A, Schott E, et al. Blood transfusions and tumor biopsy may increase HCC recurrence rates after liver transplantation. J Transplant. 2017;2017:9731095. doi: 10.1155/2017/9731095. doi:10.1155/2017/9731095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang SH, Suh KS, Lee HW, Cho EH, Cho JY, Cho YB, et al. The role of (18)F-FDG-PET imaging for the selection of liver transplantation candidates among hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1655–1660. doi: 10.1002/lt.20861. doi:10.1002/lt.20861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee JW, Paeng JC, Kang KW, Kwon HW, Suh KS, Chung JK, et al. Prediction of tumor recurrence by 18F-FDG PET in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:682–687. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060574. doi:10.2967/jnumed.108.060574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kornberg A, Freesmeyer M, Bärthel E, Jandt K, Katenkamp K, Steenbeck J, et al. 18F-FDG-uptake of hepatocellular carcinoma on PET predicts microvascular tumor invasion in liver transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:592–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02516.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kornberg A, Küpper B, Thrum K, Katenkamp K, Steenbeck J, Sappler A, et al. Increased 18F-FDG uptake of hepatocellular carcinoma on positron emission tomography independently predicts tumor recurrence in liver transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2561–2563. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.115. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kornberg A, Küpper B, Tannapfel A, Büchler P, Krause B, Witt U, et al. Patients with non-[18 F]fludeoxyglucose-avid advanced hepatocellular carcinoma on clinical staging may achieve long-term recurrence-free survival after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:53–61. doi: 10.1002/lt.22416. doi:10.1002/lt.22416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee SD, Kim SH, Kim YK, Kim C, Kim SK, Han SS, et al. (18)F-FDG-PET/CT predicts early tumor recurrence in living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transpl Int. 2013;26:50–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01572.x. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee SD, Kim SH, Kim SK, Kim YK, Park SJ. Clinical impact of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in living donor liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation. 2015;99:2142–2149. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000719. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee SD, Lee B, Kim SH, Joo J, Kim SK, Kim YK, et al. Proposal of new expanded selection criteria using total tumor size and (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose - positron emission tomography/computed tomography for living donor liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: The National Cancer Center Korea criteria. World J Transplant. 2016;6:411–422. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.411. doi:10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hsu CC, Chen CL, Wang CC, Lin CC, Yong CC, Wang SH, et al. Combination of FDG-PET and UCSF criteria for predicting HCC recurrence after living donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100:1925–1932. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001297. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000001297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hong G, Suh KS, Suh SW, Yoo T, Kim H, Park MS, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein and (18)F-FDG positron emission tomography predict tumor recurrence better than Milan criteria in living donor liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2016;64:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.033. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takada Y, Kaido T, Shirabe K, Nagano H, Egawa H, Sugawara Y, et al. Significance of preoperative fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in prediction of tumor recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a Japanese multicenter study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:49–57. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.412. doi:10.1002/jhbp.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]