Abstract

Pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) disease epidemiology in sub-Saharan Africa is not as well described as for pulmonary tuberculosis. Earlier reviews of global NTM epidemiology only included subject-level data from one sub-Saharan Africa country. We systematically reviewed the literature and searched PubMed, Embase, Popline, OVID and Africa Wide Information for articles on prevalence and clinical relevance of NTM detection in pulmonary samples in sub-Saharan Africa. We applied the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Disease Society of America criteria to differentiate between colonisation and disease. Only 37 articles from 373 citations met our inclusion criteria. The prevalence of pulmonary NTM colonization was 7.5% (95% CI: 7.2%–7.8%), and 75.0% (2325 of 3096) occurred in males, 16.5% (512 of 3096) in those previously treated for tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium complex predominated (27.7% [95% CI: 27.2–28.9%]). In seven eligible studies, 27.9% (266 of 952) of participants had pulmonary NTM disease and M. kansasii with a prevalence of 69.2% [95% CI: 63.2–74.7%] was the most common cause of pulmonary NTM disease. NTM species were unidentifiable in 29.2% [2,623 of 8,980] of isolates. In conclusion, pulmonary NTM disease is a neglected and emerging public health disease and enhanced surveillance is required.

Introduction

The epidemiology of pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) - M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, M. africanum, M. canetti, M. microti, M. pinnipedii and M. caprae - is better known than for NTM1. NTM is a designation used for a large number of potentially pathogenic and non-pathogenic environmental mycobacterial species other than MTBC and Mycobacterium leprae.

Worldwide, pulmonary infections caused by NTM are gaining increased attention, in part, because of their increasing recognition and isolation in clinical settings, for example with better known NTM pathogens such as M. avium subsp paratuberculosis, M. marinum, etc.2,3. Although NTM were identified soon after Koch’s identification of M. tuberculosis as the cause of active tuberculosis in 1882, it was not until the 1950s that NTM were recognized to cause human pulmonary disease. Given their ubiquitous presence in the environment, it is important to distinguish colonization from active disease following isolation of NTM from pulmonary samples. In response to this challenge, the ATS/IDSA introduced stringent diagnostic criteria with clinical, radiological and microbiological components for diagnosis of pulmonary NTM disease2.

The clinical and molecular epidemiology of prevalent NTM in low and middle-income countries, also endemic for pulmonary tuberculosis, is less known because pulmonary and other disease manifestations caused by NTM pose a diagnostic challenge to microbiologists and clinicians2,4. In contrast to pulmonary tuberculosis, it is not possible to readily identify pulmonary NTM disease with the usual combination of basic mycobacteriology, clinical history, radiologic imaging and the tuberculin skin test, where applicable. The culture and molecular biology identification techniques required for NTM diagnosis are not cost effective for routine clinical practice in resource-poor health systems where priority is currently given to expanding access to diagnosis and treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis5,6. The distribution of NTM species isolated from pulmonary samples differs significantly by geographic region. However, most of these data are from the developed world and sub-Saharan Africa is under represented7,8. Although there are now emerging NTM disease data from Asia and parts of Africa, significant knowledge gaps still exist especially in sub-Saharan Africa where nine of the world’s 22 high burden tuberculosis countries are found8–11. Therefore, fears that inconclusive diagnosis based on smear microscopy or clinical symptoms and/or radiological findings could lead to misdiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis and/or inappropriate management of pulmonary NTM cases are valid. As it is especially to difficult to differentiate between NTM colonisation and NTM disease the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Disease Society of America (ATS/IDSA) defined a set of clinical and microbiological criteria to diagnose pulmonary NTM disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Disease Society of America diagnostic criteria for pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection/disease2.

| Clinical |

| 1. Pulmonary symptoms, nodular or cavitary opacities on chest radiograph, or a high-resolution computed tomographic scan that shows multifocal bronchiectasis with multiple small nodules. |

| And |

| 2. Appropriate exclusion of other diagnoses. |

| Microbiologic |

| 1. Positive culture results from at least two separate expectorated sputum samples (If the results from the initial sputum samples are non-diagnostic, consider repeat sputum acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smears and cultures). |

| OR |

| 2. Positive culture results from at least one bronchial wash or lavage. |

| OR |

| 3. Transbronchial or other lung biopsy with mycobacterial histopathological features (granulomatous inflammation or AFB) and positive culture for NTM or biopsy showing mycobacterial histopathological features (granulomatous inflammation or AFB) and one or more sputum or bronchial washings that are culture positive for NTM. |

| 4. Expert consultation should be obtained when NTM are recovered that are either infrequently encountered or that usually represent environmental contamination. |

| 5. Patients who are suspected of having NTM lung disease but who do not meet the diagnostic criteria should be followed until the diagnosis is firmly established or excluded. |

The objectives of this review are to consolidate existing data on NTM colonisation and disease (according to ATS/ISDA criteria) in sub-Saharan Africa, review the existing gaps in our knowledge of pulmonary NTM and identify future research priorities.

Methods

Literature Search and Selection Criteria

This review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines12. The overall aim of this review was to determine the prevalence of NTM in apparently healthy and diseased individuals in sub-Saharan Africa. We defined sub-Saharan Africa as all of Africa except Northern Africa.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, POPLINE, OVID and Africa Wide Information electronic databases for publications about pulmonary NTM in sub-Saharan Africa published from January 1, 1940 to October 1, 2016 using the following search terms and strategy: ((((((“nontuberculous mycobacteria”[MeSH Terms] AND “africa south of the sahara”[MeSH Terms]) OR “mycobacterium infections, nontuberculous”[MeSH Terms]) AND “africa south of the sahara”[MeSH Terms]) OR “mycobacterium infections, nontuberculous”[MeSH Terms]) AND “africa south of the sahara”[MeSH Terms]) OR ((“lung”[MeSH Terms] OR “lung”[All Fields] OR “pulmonary”[All Fields]) AND “nontuberculous mycobacteria”[MeSH Terms])) AND “africa south of the sahara”[MeSH Terms] AND ((“1940/01/01”[PDAT]: “2016/10/01”[PDAT]) AND “humans”[MeSH Terms]).

Selection process and data abstraction

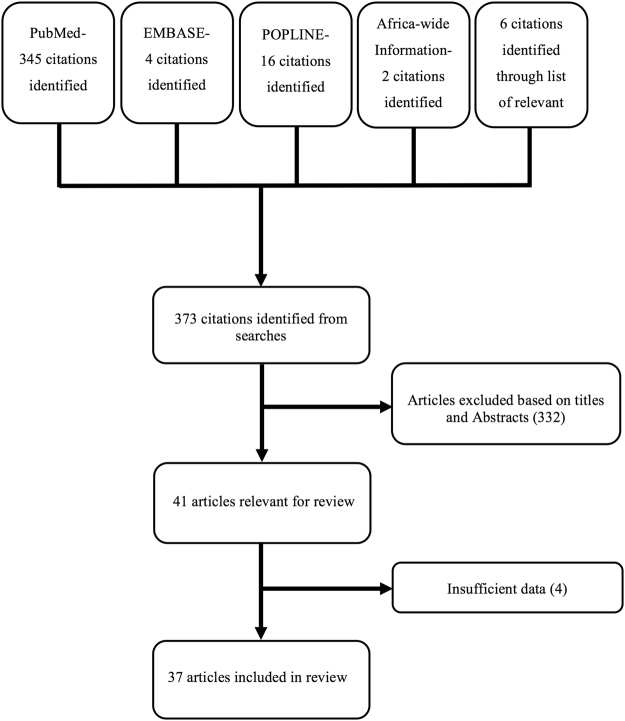

We found 373 citations from our database searches (see Fig. 1). The titles and abstracts of all the articles were screened and full-text copies of those deemed relevant obtained. In addition, the reference sections of all the retrieved articles were screened to identify other eligible citations. Only articles reporting on pulmonary samples were included. For all relevant articles, we extracted the following data using a data extraction sheet: research setting, study period, population tested and numbers, NTM species isolated, method for NTM identification, prevalence of pulmonary NTM isolation/disease, HIV co- infection rate and risk factor(s) for NTM acquisition.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search and article selection criteria.

Data analysis

In estimating country-level and overall prevalence of NTM in sub-Saharan Africa, a pooled estimate was computed based on a simple meta-analysis of the reported prevalences. Each study was weighted according to its sample size and the exact binomial used to derive the 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). We checked all retrieved articles for application of the ATS/IDSA diagnostic criteria (Table 1) for clinically relevant pulmonary NTM and recorded the proportion of patients meeting these criteria and NTM species responsible.

All extracted data were stored in Microsoft® Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, United States) and analysis carried out in STATA™ version 12.1 (College Station, Texas, United States).

Results

Description of included studies

There were only 37 relevant articles on the epidemiology of pulmonary NTM in sub-Saharan Africa as shown in Table 2. These were from studies in western (Nigeria, Mali and Ghana), southern (Zambia and South Africa [RSA]) and eastern (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Ethiopia) Africa5,6,8,10,13–44. Eleven articles were from Nigeria5,13,15–21,45,46, one from Mali22, one from Ghana23, six from Zambia6,10,24–27, two from Kenya28,29, two from Uganda30,31, three from Tanzania32–34, three from Ethiopia35–37 and eight from South Africa8,38–40,43,44.

Table 2.

Overview of studies on pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacteria in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Country | Study period | Reference | Age in years | Sample size | Sputum cultures | Most isolated NTM | Method of NTM identification | Overall prevalence of NTM isolation (%) | Pulmonary NTM patients with HIV coinfection (%) | ATS/IDSA applied/numbers meeting criteria | Risk factors for pulmonary NTM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTBC | NTM | |||||||||||

| Ethiopia | 2010 | Mathewos et al.36 | NA | 263 presumptive TB cases | 110 | 7 | NTM not classified | Immunochro-matography assay (Capilia TAUNS method) | 2.7 | NA | No | NA |

| Ethiopia | 2011 | Workalemahu et al.37 | 1–15 | 121 presumptive TB cases | 15 | 10 | M. fortuitum M. parascrofulaceum M. triviale | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 8.3 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ethiopia | 2008–09 | Gumi et al.35 | NA | 260 presumptive TB cases | 157 | 7 | M. flavescens | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 2.7 | NA | No | NA |

| Ghana | 2013–14 | Bjerrum et al.23 | ≥18 | 473 HIV infected adults | 60 | 38 | M. avium complex M. chelonae M. simiae M. fortuitum | Molecular (sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 8.0 | All HIV infected | No | HIV infection and age |

| Kenya | 2007–09 | Nyamogoba et al.28 | ≥0 | 872 presumptive TB cases | 346 | 15 | M. fortuitum M. peregrinum | Molecular (Genotype CM/As assay) | 1.7 | 46.7 | No | Previous TB HIV infection |

| Kenya | 2014–15 | Limo et al.29 | ≥0 | 210 retreatment cases | 121 | 89 | M. intracellulare M. abscessus M. fortuitum | Molecular (Genotype CM/As assay) | 42.4 | 25.8 | No | Previous TB infection |

| Mali | 2004–09 | Miaga et al.22 | 18–73 | 142 presumptive TB cases enrolled | 113 | 17 | M. avium M. palustre M. fortuitum | Molecular (sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 12.0 | 17.6 | Yes; 11 | Previous TB |

| Nigeria | 2010–11 | Olutayo et al.13 | 319 presumptive TB cases | 122 | 26 | NA | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay) | 8.2 | 46.2 | No | HIV infection, age | |

| Nigeria | 2008–09 | Cadmus et al.46 | NA | 23 presumptive cases | 11 | 9 | M. avium complex | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 39.1 | NA | No | NA |

| Nigeria | 2010–11 | Gambo et al.15 | NA | 952 presumptive TB cases | 254 | 65 | NTM not classified | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay) | 6.8 | 40.0 | No | HIV infection, TB |

| Nigeria | 2010–11 | Gambo et al.5 | 18 | 1603 TB presumptive TB cases | 375 | 69 | M. intracellulare M. abscessus M. fortuitum M. gordonae | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay) | 4.3 | 40.0 | No | HIV infection, TB |

| Nigeria | 2008–09 | Asuquo et al.16 | 10–70 | 137 presumptive TB cases | 81 | 4 | M. fortuitum M. avium species M. abscessus | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay) | 2.9 | 50.0 | No | HIV infection |

| Nigeria | 1983 | Idigbe et al.17 | NA | 668 presumptive TB cases | NA | NA | M. avium M. kansasii M. fortuitum | Conventional biochemical methods | 11.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Nigeria | 1982-93 | Idigbe et al.18 | NA | NA | NA | NA | M. avium M. kansasii M. xenopi M. fortuitum | Conventional biochemical methods | NA | NA | No | NA |

| Nigeria | NA | Mawak et al.45 | ≥14 | 329 presumptive cases | 50 | 15 | M. avium M. kansasii M. fortuitum | Conventional biochemical methods | 4.6 | NA | No | NA |

| Nigeria | 2007–09 | Daniel et al.19 | 25–80 | 102 TB patients (41 new s + and 61 s + retreatment cases) | 70 | 7 | M. fortuitum M. intracellulare M. chelonae | Conventional biochemical methods | 6.9 | 15.0 | No | Previous TB |

| Nigeria | NA | Allana et al.20 | NA | NA | NA | NA | M. avium M. kansasii M. fortuitum | Conventional biochemical methods | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nigeria | 1963 | Beer et al.21 | ≥1 | NA | 2682 | 149 | Runyon 111 and 1 V organisms | Conventional biochemical methods | 6.0 | NA | No | Previous TB |

| South Africa | 2006–07 | Clare et al.38 | Median age–44 | 2496 presumptive TB cases | 421 | 232 | M. kansasii M. gordonae | Conventional biochemical methods | 9.3 | 31.9 | No | HIV infection |

| South Africa | 1996–97 | Corbett et al.39 | NA | TB presumptive cases | NA | 118 | M. kansasii M. fortuitum M. scrofulaceum | Conventional biochemical methods | NA | 34.0 | Yes; 32 | Previous TB, silicosis |

| South Africa | 1993–96 | Corbett et al.40 | ≥18 | 594 mine workers | NA | 406 NTM | M. kansasii M. fortuitum M. avium complex | Conventional biochemical methods | 68.4 | 13.1 | Yes; 206 | HIV infection, silicosis |

| South Africa | 1993–96 | Corbett et al.39 | ≥18 | 243 NTM infected suspects | 92 | 243 | M. kansasii M. fortuitum M. intracellulare | Conventional biochemical methods | 100 | NA | No | Previous TB, silicosis |

| South Africa | 1993–96 | Corbett et al.40 | ≥18 | 406 gold miners | NA | 261 NTM patients | M. kansasii M. scrofulaceum | Conventional biochemical methods | 64.3 | NA | No | Previous TB, HIV infection |

| South Africa | 2001–05 | Hartherill et al.43 | 18 (13–23) months | 1732 presumptive TB cases | 94 | 109 | M. intracellulare M. gastri M. avium | Molecular (RFPCR of 65 KD hspgene) | 6.3 | 4.2 | Yes; 8 | Previous TB |

| South Africa | 2009 | Sookan et al.44 | NA | 200 NTM suspects | NA | 133 NTM patients | M. avium complex. M. RGM M. gordonae | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay) | 66.5 | NA | No | NA |

| South Africa | 2008 | Hoefsloot et al.8 | NA | NA | NA | 5646 NTM patients | MAC M. kansasii M. scrofulaceum M. gordonae | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay, AccuProbe assays, hsp 65 PCR–restriction enzyme analysis, Inno–Lipa Mycobacteria and biochemical methods | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tanzania | 2012–13 | Hoza et al.33 | 40 7–88 | 372 presumptive TB cases | 85 | 36 | M. gordonae M. interjectum M. avium complex M. scrofulaceum | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay) | 9.7 | 33 | No | HIV infection and age |

| Tanzania | 2011 | Haraka et al.34 | 35 | 1 HIV negative patient with prior TB | NA | 1 | M. intracellulare | Molecular (Genotype CM/AS assay) | 100 | 100 | Yes;1 | Previous TB |

| Tanzania | 2001–13 | Katale et al.32 | NA | 472 presumptive TB cases | NA | 12 | M. chelonae M. abscessus M. spaghni | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 2.5 | NA | No | NA |

| Uganda | 2009 | Asimwe et al.30 | 12–18 | 2200 (710 infants and 1490 adolescents presumptive TB cases) | 8 | 95 | M. fortuitum M. szulgai M. gordonae | Molecular (Genotype CM/As assay) | 4.3 | NA | No | NA |

| Uganda | 2012–13 | Bainomugisa et al.31 | NA | 241 presumptive TB cases | 95 | 14 | M. avium M. kansasii | Molecular (Polymerase Chain Reaction of 16S rDNA using the Light cycler) | 5.8 | NA | No | NA |

| Zambia | 2009–12 | Mwikuma et al.25 | NA | 91 NTM suspected isolates | NA | 54 | M. intracellulare M. lentiflavum. M. avium | Molecular (Genotype CM/As assay) | 59.3 | NA | No | NA |

| Zambia | NA | Kapta et al.24 | ≥1 | 6123 presumptive TB cases enrolled | 265 | 923 | NTM not identified | Immunochromatography assay (Capilia TAUNS method) | 15.1 | 5.8 | No | TB and HIV infection |

| Zambia | 2001 | Buijtels et al.26 | ≥15 | 167 chronically ill patients | 74 | 93 | M. intracellulare M. lentiflavum M. chelonae | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 55.6 | 79.0 | Yes; 7 | Previous TB HIV infection |

| Zambia | 2001 | Buijtels et al.10 | ≥25 | 4 presumptive TB cases | NA | 4 | M. lentiflavum M. goodie | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 100.0 | 33.0 | No | HIV infection, damaged lungs |

| Zambia | 2011-12 | Malama et al.27 | NA | 100 presumptive TB cases | 46 | 9 | M. intracellulare M. abscessus M. chimera | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 9.0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Zambia | 2002–03 | Buijtels et al.6 | ≥15 | 565 (180 chronically ill patients and 385 healthy controls) | 205 | 93 | M. intracellulare M. lentiflavum. M. avium | Molecular (Sequencing of 16S rRNA gene) | 16.5 | 45.6 | Yes; 1 | Previous TB HIV infection, and use of tap water |

NA = Data not available in article.

Where methods of identification were reported, molecular techniques (n = 26) were the most frequently used to identify NTM species, followed by conventional biochemical testing identification tools (n = 9) and immunochromatographic assays (n = 2). The molecular diagnostic methods used were Restriction Fragment Polymerase Chain Reaction (RFPCR) of the 65KD hsp gene, Genotype CM/AS assay (Hain Life science, Nehren, Germany), and 16S rRNA gene sequencing analysis in one, eleven and fourteen studies respectively. Identification methods also varied over time and a dramatic rise in the use of molecular methods was observed in the period 2000-2016. Biochemical and phenotypic tools were the only methods used for NTM identification before 2000. Despite this transition in identification methods used over time, there was no major change in diversity of NTM species isolated in the period before and after the year 2000 as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Non–tuberculous mycobacteria species isolated from sub-Saharan Africa, 1965–2016‡.

| Non-tuberculous mycobacteria species | Prior 2010 Biochemical identification methods | After 2010 Molecular identification methods | Previously associated with disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. intracellulare | Y | Y | Y |

| M. avium | Y | Y | Y |

| M. kansasii | Y | Y | Y |

| M. chelonae | Y | Y | Y |

| M. abscessus | Y | Y | Y |

| M. fortuitum | Y | Y | Y |

| M. scrofulaceum | Y | Y | Y |

| M. lentiflavum | Y | Y | Y |

| M. interjectum | Y | Y | Y |

| M. peregrinum | Y | Y | N |

| M. gordonae | Y | Y | N |

| M. xenopi | Y | Y | Y |

| M. malmoense | Y | Y | Y |

| M. moriokaense | Y | Y | N |

| M. kumamotonense | N | Y | N |

| M. kubicae | Y | Y | N |

| M. gordonae | Y | Y | N |

| M. simiae | Y | Y | Y |

| M. palustre | Y | Y | Y |

| M. indicus pranii | N | Y | N |

| M. elephantis | N | Y | N |

| M. flavascens | Y | Y | N |

| M. bouchedurhonense | N | Y | N |

| M. chimera | N | Y | Y |

| M. europaeum | N | Y | N |

| M. neoaurum | N | Y | N |

| M. asiaticum | Y | Y | N |

| M. nonchromogenicum | N | Y | N |

| M. gastri | Y | Y | N |

| M. nebraskense | Y | Y | N |

| M. confluentis | Y | Y | N |

| M. porcinum | Y | Y | Y |

| M. terrae | Y | Y | N |

| M. seoulense | Y | Y | N |

| M. engbackii | Y | Y | N |

| M. parascrofulaceum | Y | Y | N |

| M. triviale | Y | Y | N |

| M. scrofulaceum | Y | Y | Y |

| M. szulgai | Y | Y | Y |

| M. heckeshornense | Y | Y | N |

| M. poriferae | Y | Y | N |

| M. spaghni | Y | Y | N |

| M. goodie | Y | Y | N |

| M. aurum | Y | Y | N |

| M. conspicum | Y | Y | N |

| M. mucogenicum | Y | Y | N |

| M. rhodesia | Y | Y | N |

| M. gilvum | Y | Y | N |

| M. genevanse | N | Y | N |

| M. intermidium | N | Y | N |

| M. fortuitum 11/M. magaritense | N | Y | Y |

Synthesis of Results

Epidemiology of Non-tuberculous Mycobacteria

The overall prevalence of NTM in pulmonary samples in sub-Saharan Africa derived from all 37 papers reviewed was 7.5% (95% CI: 7.2–7.8%). The median age of participants was 35 (Interquartile range, IQR 16–80) years based on 17 of 37 studies with age data. The majority (2325 [75.0%] of 3096) of subjects with NTM were males. Patients in 12 of 37 studies (32.4%) had a previous history of pulmonary tuberculosis and 15 (40.5%) were co-infected with HIV.

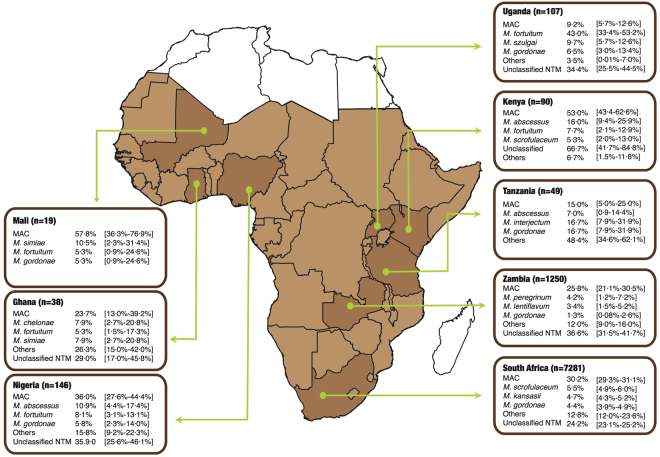

MAC species accounted for 28.0% (95% CI: 27.2–28.9%) of all NTM isolated and was the most frequently encountered NTM found in pulmonary samples in 19 of 37 studies. The prevalence of MAC ranged from 15.0% (95% CI: 5.05–25.0%) in Tanzania to 57.8% (95% CI: 36.3–76.9%) in Mali as shown in Fig. 2 (along with country HIV prevalence in the legend47). There was regional variability in the distribution of NTM for example; 76.4% (95% CI: 74.8–77.9%) i.e. 2,355 of 3,084 MAC isolates from South Africa were M. intracellulare, while all MAC isolates from Mali were M. avium. Similarly, while M. kansasii was the third most isolated NTM in sub-Saharan Africa overall (4.7% [95% CI: 4.3–5.1%]), it was the top NTM in five (62.5%) of eight studies in South Africa.

Figure 2.

The distribution of the top four non-tuberculous mycobacteria species identified from pulmonary samples in Mali (HIV 1.4%), Ghana (HIV prevalence 1.3), Nigeria (HIV 3.1%), Uganda (HIV 7.1%), Kenya (HIV 5.9%), Tanzania (HIV 4.7%), Zambia (HIV 12.9%), and Republic of South Arica (HIV 19.2%), without considering clinical relevance. Data compiled from refs5,6,8,10,13,15–17,19–33,35–46. HIV prevalence compiled from ref.47.

Other slow growing mycobacteria isolates, though less prevalent than MAC, were M. scrofulaceum 7.0% (95% CI: 6.4–7.5%) and M. gordonae 3.8% (95% CI: 3.4–4.3%). The rapidly growing mycobacteria i.e. M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, and M. abscessus accounted for just 1.2% (95% CI: 1.0–1.4%) of all NTM isolates from sub-Saharan Africa. Rapidly growing mycobacteria were reported predominantly from eastern African countries with M. fortuitum (43.0% [95% CI: 34.4–53.2%]) and M. abscessus (16.0% [95% CI: 9.4–25.9%]) as the top and second ranked NTM isolates from Uganda and Kenya respectively.

Among the 70.8% (6357 of 8980) fully speciated isolates in this review, there were 0.9% (56) M. lentiflavum, 0.9% (55) M. malmoense, 0.7% (43) M. xenopi, 0.4% (24) M. gastri, 0.3% (16) M. szulgai, 0.2% (15) M. flavescens, and 0.2% (11) M. interjectum. Unfortunately, 29.2% (95% CI: 28.1–30.1%) i.e. 2,623 of all 8,980 NTM isolates were not identified to species level.

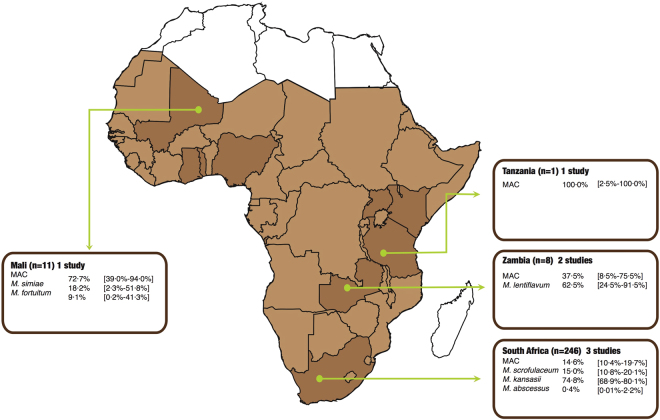

Epidemiology of Pulmonary Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial Disease

One particular challenge in studying NTM infection is the difficulty in differentiating between NTM colonisation of patients (due to the mere presence of the bacteria in the environment) and actual pulmonary disease. Therefore the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Disease Society of America (ATS/IDSA) defined a combination of stringent clinical and microbiological criteria to conclusively determine pulmonary disease (see Table 1). To evaluate the geographical distribution of disease-causing NTM only, we excluded 30 articles that only reported on the detection of NTM without applying ATS/IDSA criteria and therefore could not show evidence of pulmonary disease. Only seven (19.0%) of the 37 articles were ATS/ISDA compliant and could be investigated in respect to the epidemiology of clinically relevant NTM6,22,26,34,39,40,43. Although these studies had 3,319 participants, only 962 (28.9%) had sufficient information to apply the ATS/IDSA criteria and of these, 266 (27.7%) met the definition of pulmonary NTM disease. M. kansasii, isolated in 184 (69.2%) of 266 cases, was the most predominant cause of confirmed pulmonary NTM disease, followed by M. scrofulaceum (13.9%), MAC (13.5%), M. lentiflavum (1.9%), M. simiae (0.8%), M. palustre (0.4%) and M. abscessus (0.4%).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of NTM species causing pulmonary NTM disease in sub-Saharan Africa by country. The studies investigating the clinical relevance of NTM isolates varied substantially in design, participant characteristics and background HIV prevalence (see Table 2). They ranged from a Zambian study that evaluated the clinical relevance of NTM isolated from 180 chronically ill patients and 385 healthy controls and found only 1.1% of isolates were clinically relevant6, to a Malian study in patients with primary and chronic pulmonary tuberculosis where 57.9% of isolated NTM were clinically relevant22.

Figure 3.

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria species causing pulmonary disease (based on ATS/ISDA criteria) found in respiratory specimens in sub-Saharan Africa. Data compiled from refs6,22,26,34,39,40,43.

Clinical and Radiological Signs, and Associated Morbidities

Of 3096 participants with NTM isolates, 80.7% (2498) and 87.5% (2,709) had clinical and radiological information respectively5,6,15,16,21,22,24–26,29,34,38–40,43,45. Clinical characteristics for NTM subjects closely mimicked those of pulmonary tuberculosis, as summarized in Table 4. There were radiological abnormalities in 79.0% (2141) of 2709 subjects, while 21.0% (568) had normal chest radiographs. Of the 512 with prior lung disease, 87.1% (446) had a history of tuberculosis and 12.9% (66) had bronchiectasis. In those with concurrent conditions, 50.2% (442) of 880 were coinfected with HIV, 28.2% (248) reported gastrointestinal diseases and 8.6% (76) complained of body weakness. Other characteristics are shown on Table 4.

Table 4.

Clinical and radiographic characteristics for patients with pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacteria infections in sub-Saharan Africa, 1965–2016 (N = 3096).

| Characteristic | Numbers (%) |

|---|---|

| Clinical signs n = 2, 498 | |

| Cough ≥ 2 weeks | 950 (38.0%) |

| Chest pain | 684 (27.3%) |

| Significant weight loss | 546 (21.9%) |

| Fever ≥ 2 | 455 (18.2%) |

| Night sweats | 211 (8.4%) |

| Haemoptysis | 27 (1.1%) |

| Dyspnoea | 19 (0.8%) |

| Previous lung disease n = 512 | |

| Bronchiectasis | 66 (12.9%) |

| Tuberculosis | 446 (87.1%) |

| Radiographic findings n = 2709 | |

| Abnormal, suggestive of TB | 1009 (37.2%) |

| No pathological changes | 568 (20.9%) |

| Tuberculosis | 446 (16.5%) |

| Nodules | 203 (7.5%) |

| Fibrosis | 140 (5.2%) |

| Cavitation | 127 (4.7%) |

| Prior focal radiological scarring | 107 (4.0%) |

| Bronchiectasis | 66 (2.4%) |

| Abnormal, not consistent with TB | 24 (0.9%) |

| Milliary TB | 19 (0.7%) |

| Concurrent conditions n = 880 | |

| HIV infection | 442 (50.2%) |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 248 (28.2%) |

| Weakness | 76 (8.6%) |

| Lymph node enlargement | 52 (6.0%) |

| Splenomegaly | 21 (2.4%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (2.5%) |

| Hepatomegaly | 19 (2.2%) |

Discussion

We provide an overview of the epidemiology and geographical distribution of NTM species isolated from pulmonary samples in sub-Saharan Africa. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive review of pulmonary NTM in this part of the world. Similar to reviews by other authors, our findings suggest diversity in prevalent NTM species, geographical variation in NTM distribution and their clinical relevance across the sub-continent48.

The global collection of NTM isolated from pulmonary samples reported by Hoefsloot et al.8 in 2008 included isolates from only one sub-Saharan Africa country, South Africa. The update in 2013 by Kendall et al. did not improve significantly on the earlier review with respect to additional African NTM isolates1. Despite the relative scarcity of local data, it is important to highlight that this review is the first to include NTM data for nine countries in sub Saharan Africa.

Overall, we found a predominance of MAC from pulmonary samples in countries of Western, Eastern and Southern Africa. M. scrofulaceum and M. kansasii were predominant in Southern Africa and the rapidly growing mycobacteria (M. abscessus, M. fortuitum and M. chelonae) in Eastern Africa. These findings are consistent with the predominance of MAC in the epidemiology of NTM in North America1,2,49, Europe50, Australia51 and East Asia14. The relative preponderance of the two members of the MAC family also varied by region with M. intracellulare predominating in South Africa while all MAC isolates from Mali were M. avium. However, the South African study had a much bigger sample size compared to the Malian study. While MAC was the most frequently implicated NTM in colonisation, M. kansasii was the most common in pulmonary NTM disease. The dominance of M. kansasii as well as the presence of M. scrofulaceum in South Africa was speculated to be linked to mining activities and significant urbanisation in the country, resulting in a socio-economically disadvantaged population7,52,53, working in the mines, frequently suffering from silicosis, while living in poor, overcrowded environments (also see Table 2). When the South Africa pulmonary NTM data is excluded, MAC is the major cause of pulmonary NTM disease as reported in North America, Europe, Australia and Asia1. Because relatively few studies in this review applied the ATS/IDSA criteria for confirmation of pulmonary NTM disease, it is difficult to reach conclusions regarding the dominant NTM species causing pulmonary disease in sub-Saharan Africa.

The reason for the observed geographical variation in NTM populations across Africa is still unknown, and could be due to environmental factors associated with the differing geographical country locations. Unfortunately included studies were not designed to investigate sub-regional geographical variation and did not systematically collect environmental data. Ideally future studies on NTM in Africa could address this issue.

In contrast to observations from other parts of the world, especially in Europe, where M. malmoense and M. xenopi are well known for causing pulmonary NTM disease1,54,55, these NTM were not represented in the limited number of studies reviewed here. M. xenopi was rare in sub-Saharan Africa, which is not unexpected considering its association with hot water delivery systems that are less developed in sub-Saharan Africa compared to industrialised countries2,56.

Pulmonary NTM was commonly associated with a history of previous pulmonary tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa compared to Europe and North America. This is not surprising given the high incidence of MTBC disease in sub-Saharan Africa57,58. Pulmonary tuberculosis is associated with significant sequelae that have not been adequately studied in sub-Saharan Africa. The associated structural lung damage, chronic pulmonary obstructive disease and infections most likely favour colonization by NTM and other pathogens59. It is also likely that the increasing isolation of NTM has come from investigation of patients with chronic pulmonary disease including those complicating previous pulmonary tuberculosis6,22. In light of this, the clinical, radiological and microbiologic criteria of the ATS\IDSA is important for distinguishing colonization from pulmonary NTM, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa that is endemic for MTBC60.

Many rarely isolated NTM were also identified in presumptive tuberculosis patients, for example M. genavense, M. gilvum, M. intermedium, M. poriferae, M. spaghni, M. interjectum, M. peregrinum, M. moriokaense, M. kumamotonense and M. kubicae. Although some of these species have also been isolated in other parts of the world from pulmonary samples in patients with chronic bronchitis, pulmonary tuberculosis, sub-acute pneumonia and healed tuberculosis61,62, it is currently unclear what role they play in the aetiology of pulmonary disease in Africa.

The HIV-driven increase in the risk of tuberculosis disease in sub-Saharan Africa has been well described and for NTM, MAC is a particularly well described opportunistic infection in patients with AIDS. We found almost half of all cases of confirmed pulmonary NTM were also HIV co-infected. This suggests the possibility of HIV attributable pulmonary NTM beyond the now familiar disseminated MAC disease often seen in persons with AIDS.

Persons with pulmonary NTM infection in sub-Saharan Africa are younger than observed in North America, Europe and Australia where increasing age (≥50 years), structural lung damage, immunosuppressive chemotherapy for cancer, autoimmune and rheumatoid conditions are the most frequently reported risk factors for this disease1,2,59,63. Given the younger age and higher burden of pulmonary tuberculosis and HIV co-infection in sub-Saharan Africa, it is not surprising that we found pulmonary NTM infection mostly in the 33–44 year-age group. As the ATS/ISDA compliant studies did not describe the clinical characteristics of individual NTM patients, a risk-factor analysis for NTM disease could not be conducted in the present review.

Our review has a number of limitations: we only searched for English language-articles. Given the numbers of Francophone countries in sub-Saharan Africa, French-language publications may have been missed. In addition, our assessment of the clinical relevance of isolated NTM was not as comprehensive as desired because the majority of the studies did not collect the detailed clinical, radiological and microbiological data required to do this. We also could not report the full diversity of NTM in colonization and disease because almost 30% of all isolates were not fully identified to species level. Since the studies reviewed came from varied time periods during which laboratory procedures for ascertainment differed, we cannot exclude the possibility of laboratory procedures before and/or after year 2000 selecting for particular NTM species whilst inhibiting others64. For example, the wider usage of sensitive liquid culture media could in theory have selected for specific NTM species. Similarly, the increasing use of molecular methods for identification of current and historical isolates, especially for the MAC and rapidly growing mycobacteria groups, could underpin the changes to NTM taxonomy over time65–67. However, we think our results were not significantly affected because the distribution of NTM species identified in the periods before and after 2010 were similar. Given the heterogeneity of studies included in this review including laboratory methods and quality standards, some of the NTM reported here may be due to contamination especially for NTM like M.flavescens that are frequent laboratory contaminants. It is possible for example that all seven M. flavescens are contaminants. In more than half of 26 studies that used molecular techniques to identify NTM, 16s rDNA sequencing was used. However, this method has a limitation in that it is not fully capable of distinguishing between all the different NTM species for example M. abscessus and M. chelonae. Therefore, it is possible some species have been misidentified or misclassified in these studies.

To conclude, we have provided the first detailed review of pulmonary NTM in sub-Saharan Africa and highlight the contribution of NTM to the aetiology of tuberculous-like pulmonary disease in the sub-continent. Our review also suggests that the presence of NTM as commensals in pulmonary samples may confound the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis, especially in those with a previous history of tuberculosis and/or other chronic respiratory conditions.

Additional research and surveillance is required for investigation of the full contribution of NTM to pulmonary disease, to describe the full repertoire of prevalent and incident NTM, and to determine the role of risk factors (particularly HIV/AIDS) for colonization and/or disease. Given the risk of over diagnosis of NTM in pulmonary samples as tuberculosis disease, resulting in repeated courses of treatment in previously treated tuberculosis patients, investments in, and development of, point of care diagnostics for NTM are required.

Evidence before this Study

We searched PubMEd, Embase and other databases for the terms “nontuberculous mycobacteria*”, “pulmonary*”, “africa south of the sahara*”, “lung”, and “human”. We searched for English-language articles published up to Oct 1, 2016 and reviewed all eligible articles and their reference lists. Earlier reviews only included NTM isolates, subject level data from just one sub-Saharan Africa country and did not investigate the clinical relevance of isolated NTM.

Added Value of this Study

This is the first review to utilise all available data to provide a detailed picture of the clinical and molecular epidemiology of NTM isolated from pulmonary samples in sub-Saharan Africa. As a result, we find there is a substantial burden of pulmonary NTM in the sub-continent. With seven out of every 100 presumptive tuberculosis cases either colonised or diagnosed with confirmed pulmonary NTM, the likelihood of pulmonary tuberculosis over diagnosis especially in those with previous history of tuberculosis requires further investigation. In addition, we highlight the knowledge gap resulting from incomplete identification of NTM species.

Acknowledgements

The Medical Research Council Gambia (MRCG) funded this project. We also thank the Communications Department of MRCG led by Sarah Michelle Fernandes for producing the figures here. This review benefited tremendously from the use of the MRCG library resource centre. This article is published with the permission of the Director-General, Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Author Contributions

C.O. led data acquisition from relevant articles and analysis and wrote the first draft. S.M. contributed in data analysis. M.A., S.A., F.G., and I.A. provided supervision, and contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. F.G. and I.A. contributed equally. I.A. conceived the idea along with M.A. All authors were involved in writing this manuscript and gave approval for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Florian Gehre and Ifedayo M.O. Adetifa contributed equally to this work.

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25256-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

5/14/2018

A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

- 1.Kendall BA, Winthrop KL. Update on the epidemiology of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;34:87–94. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith DE, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson MM, Odell JA. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infections. Journal of thoracic disease. 2014;6:210–220. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Ingen J. Diagnosis of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;34:103–109. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aliyu G, et al. Prevalence of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections among tuberculosis suspects in Nigeria. PloS one. 2013;8:e63170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buijtels PC, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria, zambia. Emerging infectious diseases. 2009;15:242–249. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.080006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoefsloot W, et al. The rising incidence and clinical relevance of Mycobacterium malmoense: a review of the literature. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease: the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2008;12:987–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoefsloot W, et al. The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. The European respiratory journal. 2013;42:1604–1613. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00149212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fusco da Costa AR, et al. Occurrence of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection in an endemic area of tuberculosis. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013;7:e2340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buijtels PC, Petit PL, Verbrugh HA, van Belkum A, van Soolingen D. Isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria in Zambia: eight case reports. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005;43:6020–6026. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6020-6026.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed I, Jabeen K, Hasan R. Identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from clinical specimens at a tertiary care hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13:493. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. International journal of surgery. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olutayo F, Fagade O, Cadmus S. Prevalence of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Infections in Patients Diagnosed with Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Ibadan. International journal of tropical disease & health. 2016;18:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons S, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in respiratory tract infections, eastern Asia. Emerging infectious diseases. 2011;17:343–349. doi: 10.3201/eid170310060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aliyu G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of point-of-care digital chest-x-ray in HIV patients with pulmonary mycobacterial infections in Nigeria. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14:675. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0675-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pokam BT, Asuquo AE. Acid-fast bacilli other than mycobacteria in tuberculosis patients receiving directly observed therapy short course in cross river state, Nigeria. Tuberculosis research and treatment. 2012;2012:301056. doi: 10.1155/2012/301056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Idigbe EO, Anyiwo CE, Onwujekwe DI. Human pulmonary infections with bovine and atypical mycobacteria in Lagos, Nigeria. The Journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 1986;89:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Idigbe EO, et al. The trend of pulmonary tuberculosis in Lagos, Nigeria 1982–1993. Biomedical Letters. 1995;51:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel O, et al. Non tuberculosis mycobacteria isolates among new and previously treated pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Nigeria. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2011;1:113–115. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(11)60048-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allanana J, Ikeh E, Bello C. Mycobacterium species from clinical specimens in Jos, Nigeria. Nigerian J of Med. 1991;2:111–112. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beer AG, Davis GH. ‘Anonymous’ Mycobateria Isolated in Lagos, Nigeria. Tubercle. 1965;46:32–39. doi: 10.1016/S0041-3879(65)80084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maiga M, et al. Failure to recognize nontuberculous mycobacteria leads to misdiagnosis of chronic pulmonary tuberculosis. PloS one. 2012;7:e36902. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjerrum S, et al. Tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacteria among HIV-infected individuals in Ghana. Tropical medicine & international health: TM & IH. 2016;21:1181–1190. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chanda-Kapata P, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) in Zambia: prevalence, clinical, radiological and microbiological characteristics. BMC infectious diseases. 2015;15:500. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1264-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mwikuma G, et al. Molecular identification of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from clinical specimens in Zambia. Annals of clinical microbiology and antimicrobials. 2015;14:1. doi: 10.1186/s12941-014-0059-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buijtels PC, et al. Isolation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria at three rural settings in Zambia; a pilot study. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2010;16:1142–1148. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malama S, Munyeme M, Mwanza S, Muma JB. Isolation and characterization of non tuberculous mycobacteria from humans and animals in Namwala District of Zambia. BMC research notes. 2014;7:622. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyamogoba HD, et al. HIV co-infection with tuberculous and non-tuberculous mycobacteria in western Kenya: challenges in the diagnosis and management. African health sciences. 2012;12:305–311. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i3.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Limo J, et al. Infection rates and correlates of Non-TuberculousMycobacteriaamong Tuberculosisretreatment cases In Kenya. Prime Journal of Social Science. 2015;4:1128–1134. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asiimwe BB, et al. Species and genotypic diversity of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from children investigated for pulmonary tuberculosis in rural Uganda. BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bainomugisa A, et al. Use of real time polymerase chain reaction for detection of M. tuberculosis, M. avium and M. kansasii from clinical specimens. BMC infectious diseases. 2015;15:181. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0921-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katale BZ, et al. Species diversity of non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from humans, livestock and wildlife in the Serengeti ecosystem, Tanzania. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14:616. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0616-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoza, A. S., Mfinanga, S. G., Rodloff, A. C., Moser, I. & Konig, B. Increased isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria among TB suspects in Northeastern, Tanzania: public health and diagnostic implications for control programmes. BMC research notes9, 109, 10.1186/s13104-016-1928-3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Haraka, F., Rutaihwa, L. K., Battegay, M. & Reither, K. Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in non-HIV infected patient in a region with a high burden of tuberculosis. BMJ case reports2012, 10.1136/bcr.01.2012.5713 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Gumi B, et al. Zoonotic transmission of tuberculosis between pastoralists and their livestock in South-East Ethiopia. EcoHealth. 2012;9:139–149. doi: 10.1007/s10393-012-0754-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathewos B, Kebede N, Kassa T, Mihret A, Getahun M. Characterization of mycobacterium isolates from pulmomary tuberculosis suspected cases visiting Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory at Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute, Addis Ababa Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine. 2015;8:35–40. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60184-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Workalemahu B, et al. Genotype diversity of Mycobacterium isolates from children in Jimma, Ethiopia. BMC research notes. 2013;6:352. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Halsema CL, et al. Clinical Relevance of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Isolated from Sputum in a Gold Mining Workforce in South Africa: An Observational, Clinical Study. BioMed research international. 2015;2015:959107. doi: 10.1155/2015/959107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbett EL, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: defining disease in a prospective cohort of South African miners. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;160:15–21. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9812080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbett EL, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary mycobacterial disease in South African gold miners. A case-control study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;159:94–99. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9803048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corbett EL, et al. The impact of HIV infection on Mycobacterium kansasii disease in South African gold miners. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999;160:10–14. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9808052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corbett EL, et al. Mycobacterium kansasii and M. scrofulaceum isolates from HIV-negative South African gold miners: incidence, clinical significance and radiology. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:501–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatherill M, et al. Isolation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in children investigated for pulmonary tuberculosis. PloS one. 2006;1:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sookan L, Coovadia YM. A laboratory-based study to identify and speciate non-tuberculous mycobacteria isolated from specimens submitted to a central tuberculosis laboratory from throughout KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 2014;104:766–768. doi: 10.7196/samj.8017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mawak J, Gomwalk N, Bello C, Kandakai-Olukemi Y. Human pulmonary infections with bovine and environment (atypical) mycobacteria in jos, Nigeria. Ghana medical journal. 2006;40:132–136. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v40i3.55268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cadmus SI, et al. Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Isolated from Tuberculosis Suspects in Ibadan, Nigeria. Journal of pathogens. 2016;2016:6547363. doi: 10.1155/2016/6547363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa. http://www.who.int/gho/urban_health/outcomes/hiv_prevalence/en/ (Accessed 09 November 2016).

- 48.Marras TK, Daley CL. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clinics in chest medicine. 2002;23:553–567. doi: 10.1016/S0272-5231(02)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winthrop KL, Varley CD, Ory J, Cassidy PM, Hedberg K. Pulmonary disease associated with nontuberculous mycobacteria, Oregon, USA. Emerging infectious diseases. 2011;17:1760–1761. doi: 10.3201/eid1709.101929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moore JE, Kruijshaar ME, Ormerod LP, Drobniewski F, Abubakar I. Increasing reports of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1995–2006. BMC public health. 2010;10:612. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomson RM, N TM. working group at Queensland TB Control Centre Queensland Mycobacterial Reference Laboratory. Changing epidemiology of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria infections. Emerging infectious diseases. 2010;16:1576–1583. doi: 10.3201/eid1610.091201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bloch KC, et al. Incidence and clinical implications of isolation of Mycobacterium kansasii: results of a 5-year, population-based study. Annals of internal medicine. 1998;129:698–704. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-9-199811010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martin-Casabona N, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria: patterns of isolation. A multi-country retrospective survey. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease: the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2004;8:1186–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marusic A, et al. Mycobacterium xenopi pulmonary disease - epidemiology and clinical features in non-immunocompromised patients. The Journal of infection. 2009;58:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.France AJ, McLeod DT, Calder MA, Seaton A. Mycobacterium malmoense infections in Scotland: an increasing problem. Thorax. 1987;42:593–595. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.8.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jankovic M, et al. Geographical distribution and clinical relevance of non-tuberculous mycobacteria in Croatia. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease: the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2013;17:836–841. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Telisinghe L, et al. HIV and tuberculosis in prisons in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2016;388:1215–1227. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30578-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World, Health & Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2016, http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (2016).

- 59.Chan ED, Iseman MD. Underlying host risk factors for nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;34:110–123. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Griffith DE. Therapy of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2007;20:198–203. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328055d9a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rammaert B, et al. Mycobacterium genavense as a cause of subacute pneumonia in patients with severe cellular immunodeficiency. BMC infectious diseases. 2011;11:311. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lima CA, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in respiratory samples from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in the state of Rondonia, Brazil. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:457–462. doi: 10.1590/S0074-0276108042013010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Prevots DR, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2010;182:970–976. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buijtels PC, Petit PL. Comparison of NaOH-N-acetyl cysteine and sulfuric acid decontamination methods for recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. Journal of microbiological methods. 2005;62:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chien HP, Yu MC, Wu MH, Lin TP, Luh KT. Comparison of the BACTEC MGIT 960 with Lowenstein-Jensen medium for recovery of mycobacteria from clinical specimens. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease: the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2000;4:866–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tortoli E. Impact of genotypic studies on mycobacterial taxonomy: the new mycobacteria of the 1990s. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2003;16:319–354. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.2.319-354.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van Ingen J, et al. Re-analysis of 178 previously unidentifiable Mycobacterium isolates in the Netherlands in 1999–2007. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2010;16:1470–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]