Abstract

The evolutionary history of dinosaurs might date back to the first stages of the Triassic (c. 250–240 Ma), but the oldest unequivocal records of the group come from Late Triassic (Carnian – c. 230 Ma) rocks of South America. Here, we present the first braincase endocast of a Carnian dinosaur, the sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim, and provide new data regarding the evolution of the floccular and parafloccular lobe of the cerebellum (FFL), which has been extensively discussed in the field of palaeoneurology. Previous studies proposed that the development of a permanent quadrupedal stance was one of the factors leading to the volume reduction of the FFL of sauropods. However, based on the new data for S. tupiniquim we identified a first moment of FFL volume reduction in non-sauropodan Sauropodomorpha, preceding the acquisition of a fully quadrupedal stance. Analysing variations in FFL volume alongside other morphological changes in the group, we suggest that this reduction is potentially related to the adoption of a more restricted herbivore diet. In this context, the FFL of sauropods might represent a vestigial trait, retained in a reduced version from the bipedal and predatory early sauropodomorphs.

Introduction

The last two decades have witnessed a rapid development in the world of virtual palaeontology1. With the aid of non-destructive computed tomography (CT) techniques, numerous analyses of the internal skull structures of non-avian dinosaurs were carried out. Nevertheless, these studies were mainly based on Jurassic and Cretaceous specimens, whereas the brain and associated soft-tissues of the oldest representatives of the group have never been analysed in detail. The Santa Maria Formation of Brazil, together with the Ischigualasto Formation of Argentina, both Carnian in age (c. 230 Ma), record the oldest unequivocal dinosaurs2,3. Cranial remains are not scarce in these strata (e.g. refs4–7), but information on the soft tissues associated with the braincase (e.g. brain, inner ear, cranial nerves) are poorly studied (e.g. ref.8).

Here, we present the first paleoneurological study of the sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim 9. Fossils of S. tupiniquim come from the Santa Maria Formation in southern Brazil, from a locality commonly known as Cerro da Alemoa or Waldsanga (53°45′ W; 29°40′ S). The taxon is based on three fairly complete specimens [MCP 3844-PV (holotype), 3845-PV, and MCP 3946-PV9], but skull elements are only preserved in MCP 3845-PV, including the bones that form the braincase. Given its age and phylogenetic position10, S. tupiniquim is a key-taxon to understand the early evolution of Sauropodomorpha, the lineage that includes the gigantic herbivores of the Mesozoic, the sauropods10. Based on new data for S. tupiniquim, we analyse the evolution of the sauropodomorph endocast in the context of other anatomical transformations and suggest a new scenario for the evolution of the cerebellar neural tissues in the group.

Results

Endocast

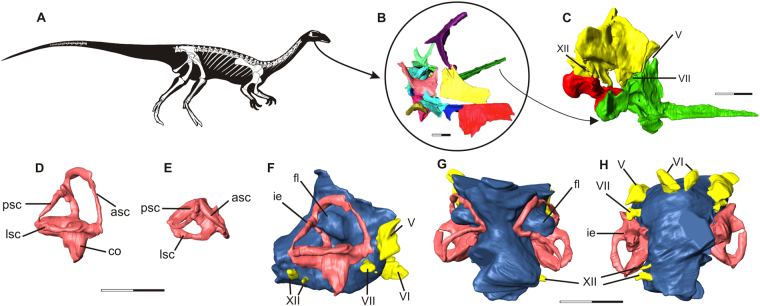

The endocast of Saturnalia tupiniquim presented here (Fig. 1) is based on the reconstruction of the soft tissues associated with the bones of the articulated portion of the preserved braincase, i.e. supraoccipital, otoccipitals (=exoccipital + opisthotic), prootics, parabasisphenoid, and basioccipital (see Supporting Information). Hence, the endocast corresponds to the posterior portion of the brain cavity of S. tupiniquim, including parts of the hindbrain, such as the cerebellum and medulla oblongata, and cranial nerves V, VI, VII, and XII. The preserved portion of the skull does not include any of the osteological correlates of the fore- or midbrain. Hence, structures such as the olfactory lobes and cranial nerves I to IV are not present in the endocast of S. tupiniquim.

Figure 1.

The early sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim. Skeletal reconstruction (A). Virtual preparation of cranial bones as preserved inside the matrix (B), with braincase highlighted in right lateral (C) view. Reconstruction of the soft tissues associated with the braincase: right inner ear in lateral (D) and dorsal (E) views, and endocast in lateral (F), dorsal (G), and, ventral (H) views. Abbreviations: asc – anterior semicircular canal; co – cochleae; fl – Floccular Fossae Lobe; ie – inner ear; lsc – lateral semicircular canal; psc – posterior semicircular canal; V – trigeminal nerve; VI – abducens nerve; VII – facial nerve; XII hypoglossal nerve. Scale bars = 1 cm.

A flexure in the endocast at the anteroposterior level of the two branches of cranial nerve XII (hypoglossal nerve) is here interpreted as the pontine flexure, with the dorsal margin of the anterior and posterior segments forming angles of approximately 45 degrees to the horizontal plane. In the anterior segment, the dorsal surface of the endocast becomes slightly more vertically orientated, at the same anteroposterior level of large protuberances in the anterolateral part of the endocast. These protuberances are associated with the floccular fossae in the endocranial cavity. It is important to stress that we here consider the floccular fossae as the fossae present in the medial surface of the periotic bones of the skull (sensu 11). Accordingly, the protuberances in the matching region of the endocast are here interpreted as corresponding to the neural tissues that filled the floccular fossae. In dinosaurs, these neural tissues might have consisted of the cerebellar flocculus and paraflocculus (see e.g. refs11,12), hereafter the FFL (sensu 11).

The spatial distribution, number, and general morphology of cranial nerves V, VI, VII, and XII (Fig. 1) in the endocast of Saturnalia tupiniquim mostly correspond to that of other dinosaurs (see e.g. refs13–18) and non-dinosaurian dinosauriforms,19. The foramen associated with the cranial nerve V (trigeminal nerve) is located on the lateral wall of the braincase, anterior to the floccular fossa. In this region of the braincase, there is no evidence of an additional foramen for the lateral branch of the mid-cerebral vein. Thus, the most likely scenario is that this branch exited the braincase via the same aperture as the trigeminal nerve. Accordingly, part of the reconstructed trigeminal nerve in the endocast might also correspond to a portion of the mid-cerebral vein. In contrast to the osteological correlates of other cranial nerves, which pierce the lateral portion of the braincase, the foramina for cranial nerve VI (abducens nerve) are located on its anteroventral surface. Typically, the pituitary fossa is seen ventral to the foramina associated with the cranial nerves VI, but its limits cannot be clearly recognized in the CT-Scan data, and the pituitary gland was not reconstructed. The foramen associated with cranial nerve VII (facial nerve) is completely enclosed by the prootic. It is located ventral to the anterior semi-circular canal of the inner ear and is narrower than those of cranial nerves V and VI. In contrast to the cranial nerves mentioned above, cranial nerve XII (hypoglossal nerve) of S. tupiniquim was reconstructed only on the right side of the endocast. The two branches of the hypoglossal nerve exited the braincase via independent apertures on the otoccipital on each side of the braincase. As is typical for dinosaurs (e.g. ref.14), the posterodorsal foramen is broader than the anteroventral one. The braincase shows a broad aperture posterior to the fenestra vestibule, which might correspond to the metotic foramen (see refs20–22); i.e. the exit of cranial nerves IX-XI. However, the path of cranial nerve IX varies greatly among archosaurs, and is not necessarily associated with the metotic foramen23. Another possibility is that an extra foramen, the vagal foramen (sensu 20), was present in the region of the exoccipital pillar of the ottocipital, representing the path for cranial nerve X, and possibly also for cranial nerve XI in taxa that possess such structure21. However, this region of the braincase is not well preserved in MCP 3845-PV, and we chose not to reconstruct cranial nerves IX-XI because of their ambiguous exit places.

The CT data also allowed the reconstruction of the inner ear anatomy of Saturnalia tupiniquim. The anterior semi-circular canal (ASC) is approximately 1.5 times higher than wide and the longest of the three canals. Its total length is c. 1.85 the length of the lateral semi-circular canal (LSC), and c. 1.54 the length of the posterior semi-circular canal (PSC). In dorsal view, ASC and PSC diverge from one another, forming an angle of about 80 degrees. Additionally, the portion of PSC between the dorsal limit of the crus commune and the posterior limit of the inner ear is anteriorly curved at an angle of c. 30 degrees; whereas the portion of ASC between its dorsal and anterior limits is straight. The crus commune is caudally curved. At approximately its mid-length, the main axis of the crus is arched at an angle of c. 20 degrees in relation to the vertical axis of the inner ear. The portion of the inner ear ventral to the semi-circular canals is shorter than the dorsoventral length of ASC, but the cochlear duct is not very well preserved, and the ventralmost limit of the cochlea is unclear.

Discussion

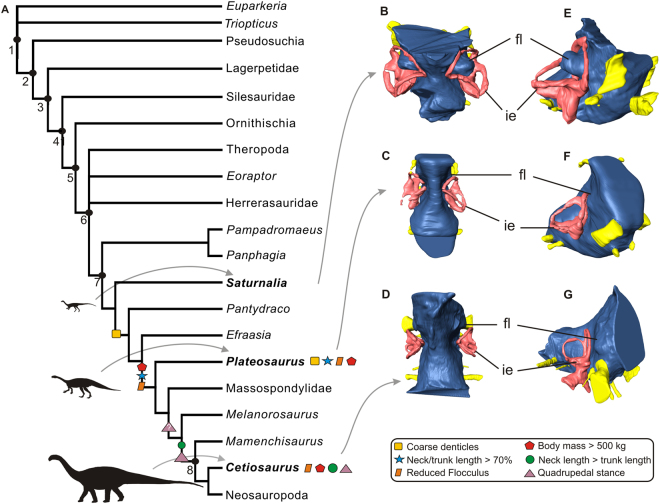

The floccular fossae lobe (FFL) is part of the systems operating to control eyes, neck, and head movements11,12,24,25. As such, it has been investigated in paleoneurological studies of dinosaurs, a group with a wide range of locomotion, feeding behaviour, and ecology (e.g. refs14,17,25). In order to trace the evolution of the FFL in sauropodomorph dinosaurs, it is necessary to determine the plesiomorphic and derived conditions of the FFL in the group. Accordingly, the presence of an enlarged protuberance in the region of the endocast corresponding to the FFL, what indicates a large volume of FFL, such as that of Saturnalia tupiniquim (Fig. 2), i.e. projecting into the space of the semi-circular canals of the inner ear (this parameter is not employed here in an attempt to capture all the spectrum of size variation in the FFL, but to discriminate between the conditions observed in Carnian sauropodomorphs and sauropods; see below), is also observed in the non-archosaurian archosauriform Triopticus primus 26 and in non-avian theropods (e.g. 14,25). Based on the size of the floccular fossae in the medial surface of the periotic bones, the condition in the non-archosaurian archosauriform Euparkeria capensis 27, the non-dinosaurian dinosauriforms Marasuchus lilloensis (pers. obs) and Lewisuchus admixtus 19, and in the silesaurid Silesaurus opolensis (pers. obs) mostly likely also correspond to the presence of a large volume of FFL. In this context, the most parsimonious scenario is that S. tupiniquim retained the plesiomorphic condition for both sauropodomorphs and dinosaurs, and that the small volume of FFL observed in sauropods (e.g. refs16,17,28) corresponds to the derived condition within the group. Furthermore, the small volume of FFL of Plateosaurus engelhardti indicates that an initial volume reduction of these neural tissues occurred in the early evolutionary history of the group, before the origin of sauropods (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Simplified Archosauriformes phylogeny highlighting character acquisition in Sauropodomorpha (A). Endocasts of Saturnalia tupiniquim (MCP-3845-PV), Plateosaurus (MB.R.5586-1), and a sauropod specimen tentatively reffered to Cetiosaurus (OUMNH J13596) in dorsal (B,C,D) and anterolateral (E,F,G) views showing the morphology of the Floccular Fossae Lobe in sauropodomorph dinosaurs. Abbreviations: fl – Floccular Fossae Lobe, ie – inner ear, 1 – Archosauriformes, 2 – Archosauria, 3 – Dinosauromorpha, 4 –Dinosauriformes, 5 – Dinosauria, 6 – Saurischia, 7 – Sauropodomorpha, 8 – Sauropoda.

It is important to stress that previous studies considered that the presence of only a small protuberance in the endocast (associated to the floccular fossae) of sauropods reflected the reduction of the flocculus of the cerebellum17. However, as observed in birds, an increase in the volume of the nodulus and the uvula could also cause a protrusion of the flocculus into the fossa, but without an increase in volume of the flocculus itself12. Thus, apparent modifications in the volume of the flocculus might be related to transformations in other structures of the brain. Another possibility is that the enlarged protuberance of the endocast related to the floccular fossae, such as that of Saturnalia tupiniquim (Fig. 1), might correspond to an artefact of soft-tissue reconstruction for extinct animals. This is because the endocranial cavity can continue to expand after brain maturity29 and parts of the fossae could have also housed vasculature tissues11,12. Accordingly, any inference on the exact volume of FFL reconstructed in an endocast should be seen with caution12,29. However, patterns of anatomical transformations in other parts of the sauropodomorph skeleton and the related shifts in ecology of the taxa belonging to the lineage suggest that the reduction in volume of the portion of the endocast associated to the floccular fossae might indeed correspond to a reduction in the volume of the neural tissues associated with it (i.e. assuming a correlation between the size of the structures and the amount of neural information they process), rather than representing only an artefact related to the presence of vasculature tissue in this region.

The apparent smaller volume of FFL observed in sauropod endocasts has been associated with their quadrupedal stance17,28,30. The rationale behind this correlation lies in the requirement of a more refined balance control in bipedalism than in quadrupedalism, in a scenario where balance is coordinated by a neurological chain that involves the FFL and the inner ear14,24. However, analyses of endocasts of other dinosaurs indicate a much more complex scenario. Saturnalia tupiniquim is a facultative biped31,32 with the condition of the FFL differing from the one of the also facultative or even obligate biped sauropodomorph Plateosaurus engelhardti 33, in which the reconstructed FFL in the endocast do not project into the space between the semicircular canals. Among bipedal theropods, taxa such as therizinosaurids25 and Tyranossaurus rex 14 exhibit reconstructed FFL that project into the space of the inner ear, but a great variation is observed among these taxa, with the FFL volume in the former being much greater than in the latter. Furthermore, some quadrupedal ornithischians34 also have the reconstructed FFL projecting into the space of the semicircular canals. Thus, the corresponding variation in volume of this structure, not only between bipedal and quadrupedal forms, but also within taxa with the same pattern of locomotion, indicates that the variation detected for the FFL in the endocast of dinosaurs is not solely related to locomotion. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that the association of a specific FFL volume to a single biological condition might be misleading11.

Tracing transformations in the endocast of sauropodomorphs alongside other osteological modifications indicate that the change in feeding behaviour, from active predators to herbivores or scavenger omnivores, is one of the factors that can be potentially associated with the reduction of the floccular and parafloccular lobes. Given the neurological link of these neural tissues with control mechanisms, such as the vestibulo ocular reflex (VOR) and vestibulo collic reflex (VCR), it has been suggested that a well-developed flocculus could be linked to active predation in dinosaurs25. Indeed, an increase in VOR capacity leads to an enhanced gaze stabilization11,24,29, which enables animals to better focus on prey while coordinating the neck and skull during fast movements. On the other hand, the VCR is linked to the control of head and neck movements, for which the nodulus and the uvula participate in the neural processing of linear head acceleration signals35. In this case, the enhancement of VCR capacity might be crucial to pursue effective attacks on small and elusive prey.

Saturnalia tupiniquim has been originally interpreted as a herbivorous animal9, mostly taking into account its sauropodomorph affinities, which was hitherto interpreted as a typically herbivore clade, rather than based on specific aspects of its anatomy. However, its tooth morphology (see Supporting Information) shows features also found in dinosaurs able to use food sources other than plants36–38. Tooth crowns are recurved and possess small serrations that are perpendicular to the carina, as is typical for faunivorous taxa37–39. Hence, based on tooth morphology alone, faunivorous or omnivorous diet reconstructions are equally likely for S. tupiniquim, but its large volume of FFL provides potential additional evidence of its predatory behaviour (see above). In contrast to the oldest Carnian sauropodomorphs, other Late Triassic members of the group, such as Efraasia minor and Plateosaurus engelhardti, possess lanceolate teeth with coarse denticles, features usually associated with a diet mainly based on plants39. These taxa might eventually have complement their diet with scavenging40, a less “active” means of gathering animal food. Moreover, the first steps towards body size increase in Sauropodomorpha happened in the least inclusive clade including P. engelhardti and sauropods41–43. The increase in body size has been demonstrated to have been crucial for the evolution of a fully herbivorous diet in Sauropodomorpha42,43. In this context, when characters of hard and soft-tissues are mapped onto a phylogeny, the loss of neurological traits potentially related to an efficient predation (i.e. FFL reduction) is detected alongside modifications associated with a more obligate herbivorous diet (Fig. 2), in a clade including taxa such as P. engelhardti and sauropods, but not S. tupiniquim and other faunivore/omnivore Carnian taxa.

Another factor that might be associated with the variation in the volume of the FFL in sauropodomorphs is the elongation of the neck in this lineage. We estimated that neck length of S. tupiniquim accounts for c. 0.56–0.60 of the trunk (see Supporting Information). This is only slightly elongated if compared with early dinosauriforms such as Marasuchus and Silesaurus, in which this proportion is not greater than 0.544,45. In early dinosaurs such as Eoraptor and Heterodontosaurus, the neck/trunk relative length varies between c. 0.5 and c. 0.5546,47. A more significant cervical elongation among sauropodomorphs is firstly observed in the minimal clade including Plateosaurus (neck length/trunk length c. 0.75) and sauropods, which typically exhibit necks longer than the trunk43. In this case, a reduction in FFL volume could be the result of the reduction in the neural processing related to the VOR. This is because in dinosaurs with elongated necks, such as Plateosaurus and sauropods, the early detection of head movement is likely to be less critical for balance because the head is further decoupled from the trunk. Nevertheless, the presence of an elongated neck could also lead to an increase in neural processing of VCR, which controls cervical posture14, 24. In this context, neck elongation seems to have also played an important role in FFL evolution in sauropodomorphs, but with opposite effects for VOR and VCR.

In conclusion, a significant reduction of the FFL in sauropodomorphs in the last stages of the Triassic (i.e. Norian) seems to be associated with anatomical modifications related to the adoption of a herbivorous diet. Given the role that the FFL have in the visual coordination and head/neck movements, this suggests that the transition to herbivory also involved neurological modifications in Sauropodomorpha (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, two caveats should be noted. First, our delimitation of what represents greater volumes of FFL (based on the projection of the corresponding portion of the endocast into the space of the inner ear – see Figs 1 and 2) fails to capture all possible variations in volume of the neural tissues. However, a reduction in the volume of the FFL (i.e. the corresponding portion of the endocast not entering the inner ear space) is already observed in Plateosaurus engelhardti, indicating that an initial reduction took place among bipedal sauropodomorphs33, before the evolution of a fully quadrupedal stance. Second, it is worth stressing that many evolutionary drivers (i.e. evolution of herbivory, adoption of a quadrupedal stance, elongation of the neck) might have played a role in the evolution of the FFL in non-sauropodan sauropodomorphs. In this case, only a throughout investigation including a larger sample of endoscasts of non-sauropodan sauropodomorph taxa alongside studies on the evolutionary drivers in extant taxa (e.g. refs11,12) will be able to clarify the evolution of the FFL in the lineage. Finally, making inferences on the lifestyle of extinct taxa using a single criterion can be misleading11, 12. Form/function correlations should be very carefully made11, and other parameters (historical and ahistorical) should be taken into account when inferring the ecology of extinct taxa48. In this sense, when analysed alongside other anatomical features, the cranial soft tissues reconstructed for Saturnalia tupiniquim are consistent with the interpretation that early sauropodomorphs had a predatory behaviour37.

Material and Methods

Specimen and CT-Scan

Computed tomography data was used to produce a virtual model of the soft tissues associated with the braincase of Saturnalia tupiniquim. The specimen was scanned at the Zoologische Staatsammlung München (Bavaria State Collection of Zoology, Munich, Germany) in a Nanotom Scan (GE Sensing & Inspection Technologies GmbH, Wunstorf Germany) using the following parameters: Voltage: 100 Kv; Current: 130 μA; 3.1 μm voxel size. 1,440 slices were generated, which were downsampled by half and segmented in the software Amira (version 5.3.3, Visage Imaging, Berlin, Germany). The CT-Scan data show that otoccipital (= exoccipital + opisthotic), parabasisphenoid (= parasphenoid + basisphenoid), basioccipital, and supraoccipital are preserved in articulation inside the matrix (see Supporting Information), allowing a precise reconstruction of the posterior portion of the endocranial cavity

Phylogeny of Sauropodomorpha

In order to trace morphological transformations and major changes in the feeding behaviour along sauropodomorph evolution, we constructed an informal supertree based on the results of the most recent phylogenetic analyses for the group and its closest relatives (e.g. refs7,22,26,36,37,49–53). The discovery of new taxa, such as Panphagia protos 54, Chromogisaurus novasi 50, Pampadromaeus barbarenai 6, and Buriolestes schultzi 37, along with the reassessment of the phylogenetic position of Eoraptor lunensis as a sauropodomorph7,37, provided new data and interpretations, but the relationships of the earliest sauropodomorphs from the Carnian Santa Maria and Ischigualasto formations are still uncertain (see e.g. ref.2). Nevertheless, the nesting of Saturnalia tupiniquim within sauropodomorphs has been consistently confirmed by independent studies7,22,26,36,37,49–53. Regarding other non-sauropod sauropodomorphs, there is a growing consensus that no clade congregates all (nor most) taxa classically treated as ‘Prosauropoda’ to the exclusion of Sauropoda. Instead, these taxa have recently been found to represent a paraphyletic array in relation to Sauropoda22,50–53.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Rößner, B. Ruthensteiner, and, S. Lautenschlager for assistance with computed tomography imaging, S. Nesbitt for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript, and R. Benson and D. Schwarz for sharing CT-Scan data of sauropodomorph dinosaurs. We are also thankful to Stig Walsh and two anonymous reviewers, which significantly contributed to improve the quality of this study. This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) – Ciência sem Fronteiras (grant 246610/2012–3 to MB), Deutsche Forschunsgsgemeinschaft (grant RA 1012/12-1 to OWMR), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (grant APQ-01110-15 to JSB), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (grant 2014/03825-3 to MCL).

Author Contribution

M.B. and M.C.L. conceptualized the study; M.B. segmented the CT-Scan data; all authors analysed the results; all authors wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11737-5

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lautenschlager S, Rücklin M. Beyond the print – virtual paleontology in science publishing, outreach, and Education. J. Paleontol. 2014;88(4):727–734. doi: 10.1666/13-085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer MC. The origins of Dinosauria: much ado about nothing. Palaeontology. 2014;57(3):469–478. doi: 10.1111/pala.12108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nesbitt SJ, Barrett PM, Werning S, Sidor CA, Charig AJ. The oldest dinosaur? A Middle Triassic dinosauriform from Tanzania. Biol. Lett. 2013;9:20120949. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sereno PC, Novas FE. The skull and neck of the basal theropod Herrerasaurus ischigualastensis. J. Vert. Paleontol. 1993;13:451–476. doi: 10.1080/02724634.1994.10011525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sereno PC, Forster CA, Rogers RR, Moneta AM. Primitive dinosaur skeleton from Argentina and the early evolution of Dinosauria. Nature. 1993;361:64–66. doi: 10.1038/361064a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabreira SF, et al. New stem-sauropodomorph (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Triassic of Brazil. Naturwissenchaften. 2011;98:1035–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00114-011-0858-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez RN, et al. A basal dinosaur from the dawn of the dinosaur Era in Southwestern Pangaea. Science. 2011;331:206–210. doi: 10.1126/science.1198467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez RN, Apaldetti C, Abelin D. Basal Sauropodomorphs from the Ischigualasto Formation. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2013;32(suppl. 6):51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langer MC, Abdala F, Richter M, Benton MJ. A sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Upper Triassic (Carnian) of southern Brazil. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 1999;329:511–517. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langer MC, Ezcurra MD, Bittencourt JS, Novas FE. The origin and early evolution of dinosaurs. Biol. Rev. 2010;85:55–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira-Cardoso S, et al. Floccular fossa size is not a reliable proxy of ecology and behaviour in vertebrates. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:2005. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01981-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh SA, et al. Avian cerebellar floccular fossa size is not a proxy for flying ability in birds. Plos One. 2013;8(6):e67176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson SD, Witmer LM. Craniofacial anatomy of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2007;2:32–102. doi: 10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[32:CAOMCT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witmer, L. M., Ridgely, R. C., Dufeau, D. L., & Semones, M. C. in Anatomical imaging: towards a new morphology (eds E. Hideki & F. Roland) 67–87 (Rokyo, Springer-Verlag, 2008).

- 15.Evans DC, Ridgely R, Witmer LM. Endocranial anatomy of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids (Dinosauria: Ornithischia): a sensorineural perspective on cranial crest function. Anat. Rec. 2009;292:1315–1337. doi: 10.1002/ar.20984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knoll F, et al. The braincase of the basal Sauropod dinosaur Spinophorosaurus and 3D reconstructions of the cranial endocast and inner ear. PlosOne. 2012;7(1):e30060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulina-Carabajal A. Neuroanatomy of Titanosaurid Dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, with comments on endocranial variability within Sauropoda. Anat. Rec. 2012;295:2141–2156. doi: 10.1002/ar.22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paulina-Carabajal A, Lee Y-N, Jacobs LL. Endocranial Morphology of the Primitive Nodosaurid Dinosaur Pawpawsaurus campbelli from the Early Cretaceous of North America. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0150845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bittencourt JS, Arcucci AB, Marsicano CA, Langer MC. Osteology of the Middle Triassic archosaur Lewisuchus admixtus Romer (Chañares Formation, Argentina), its inclusivity, and relationships amongst early dinosauromorphs. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2014;13(3):189–219. doi: 10.1080/14772019.2013.878758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gower DJ, Weber E. The braincase of Euparkeria, and the evolutionary relationships of avialans and crocodilians. Biol. Rev. 1998;73:367–411. doi: 10.1017/S0006323198005222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobral, G., Hipsley, C, A., & Müller, J. Braincase redescription of Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) based on computed tomography. J. Vert. Paleontol. 32,1090–1102 (2012).

- 22.Bronzati, M., & Rauhut, O. W. M. Braincase redescription of Efraasia minor Huene, 1908 (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic of Germany, with comments on the evolution of the sauropodomorph braincase. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. zlx029 (2017).

- 23.Rieppel O. The recessus scalae tympani and its bearing on the classification of reptiles. J. Herpetol. 1985;19(3):373–384. doi: 10.2307/1564265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witmer LM, Chatterjee S, Franzosa J, Rowe T. Neuroanatomy of flying reptiles and implications for flight, posture and behaviour. Nature. 2003;425:950–953. doi: 10.1038/nature02048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lautenschlager S, Rayfield EJ, Altangerel P, Zanno LE, Witmer LM. The Endocranial Anatomy of Therizinosauria and Its Implications for Sensory and Cognitive Function. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stocker MR, et al. A Dome-Headed Stem Archosaur Exemplifies Convergence among Dinosaurs and Their Distant Relatives. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:2674–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sobral G, et al. New information on the braincase and inner ear of Euparkeria capensis Broom: implications or diapsid and archosaur evolution. R. Soc. Open. Sci. 2016;3:160072. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balanoff AM, Bever GS, Ikejiri T. The braincase of Apatosaurus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) based on computed tomography of a new specimen with comments on variation and evolution in Sauropod Neuroanatomy. Am. Mus. Novit. 2010;3677:1–29. doi: 10.1206/591.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witmer LM, Ridgely RC. New Insights Into the brain, braincase, and ear region of Tyrannosaurs (Dinosauria, Theropoda), with implications for sensory organization and behaviour. Anat. Rec. 2009;292:1266–1296. doi: 10.1002/ar.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterjee S, Zheng Z. Cranial anatomy of Shunosaurus, a basal sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of China. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2002;136:145–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00037.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Langer MC. The sacral and pelvic anatomy of the stem-sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim (Late Triassic, Brazil) Paleobios. 2003;23(2):1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langer MC, França MAG, Gabriel S. The pectoral girdle and forelimb anatomy of the stem sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim (Late Triassic, Brazil) Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 2007;77:113–137. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mallison H. The digital Plateosaurus I: Body mass, mass distribution and posture assessed using CAD and CAE on a digitally mounted complete skeleton. Palaeontol. Electron. 2010;13(2):8A. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leahey LG, Molnar RE, Carpenter K, Witmer LM, Salisbury SW. Cranial osteology of the ankylosaurian dinosaur formerly known as Minmi sp. (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the Lower Cretaceous Allaru Mudstone of Richmond, Queensland, Australia. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1475. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker MF, et al. The Cerebellar Nodulus/Uvula Integrates Otolith Signals for the Translational Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex. Plos One. 2010;5(11):e13981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nesbitt SJ, et al. Ecologically distinct dinosaurian sister group shows early diversification of Ornithodira. Nature. 2010;464(4):95–98. doi: 10.1038/nature08718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cabreira SF, et al. A unique Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage reveals dinosaur ancestral anatomy and diet. Curr. Biol. 2016;26(22):3090–3095. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrett PM, Butler RJ, Nesbitt SJ. The roles of herbivory and omnivory in early dinosaur evolution. Earth. Env. Sci. T. R. Soc. 2010;101:383–396. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrett PM, Upchurch P. The evolution of feeding mechanisms in early sauropodomorph dinosaurs. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 2007;77:91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett, P. M. in Evolution of Herbivory in Terrestrial Vertebrates: Perspectives from the Fossil Record (ed H. –D. Sues) 42–78 (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

- 41.Benson RBJ, et al. Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage. PLoS. Biol. 2014;12(5):e1001853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sander PM, et al. Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: the evolution of gigantism. Biol. Rev. 2011;86:117–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rauhut, O. W. M., Fechner, R., Remes, K., & Reis, K. in Biology of the sauropod dinosaurs: understanding the life of giants (eds N. Klein, K. Remes, C. T. Gee, & P. M. Sander) 119–149 (Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 2011)

- 44.Sereno, P. C., & Arcucci, A. B. Dinosaurian precursors from the Middle Triassic of Argentina: Marasuchus lilloensis, n. gen. J. Vert. Paleontol. 14, 53–73.

- 45.Piechowsky R, Dzik J. The axial skleton of Silesaurus opolensis. J. Vert. Paleontol. 2010;30:1127–1141. doi: 10.1080/02724634.2010.483547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santa Luca AP. The postcranial skeleton of Heterodontosaurus tucki (Reptilia, Ornithischia) from the Stormberg of South Africa. Ann. S. Afr. Mus. 1980;79:159–211. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sereno PC, Martínez RN, Alcober O. Osteology of Eoraptor lunensis (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha) J. Vert. Paleontol. 2012;32(sup 1):83–179. doi: 10.1080/02724634.2013.820113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez RN, Alcober OA. A Basal Sauropodomorph (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Triassic, Carnian) and the Early Evolution of Sauropodomorpha. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(2):e4397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Novas FE, et al. An enigmatic plant-eating theropod from the Late Jurassic period of Chile. Nature. 2015;522:331–334. doi: 10.1038/nature14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ezcurra MD. A new early dinosaur (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic of Argentina: a reassessment of dinosaur origin and phylogeny. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2010;8(3):371–425. doi: 10.1080/14772019.2010.484650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yates AM, Bonnan MF, Nevelling J, Chinsamy A, Blackbeard MG. A new transitional sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and the evolution of sauropod feeding and quadrupedalism. Proc. R. Soc. London B. 2010;277(1682):787–794. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pol D, Garrido A, Cerda IA. A new sauropodomorh dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Patagonia and the origin and evolution of the Sauropod-type sacrum. Plos ONE. 2011;6(1):e14572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McPhee BW, et al. A new basal sauropod from the pre-Toarcian Jurassic of South Africa: evidence of niche-partitioning at the sauropodomorph-sauropod boundary? Sci. Rep. 2015;5:13224. doi: 10.1038/srep13224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez RN, Alcober OA. A Basal Sauropodomorph (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Triassic, Carnian) and the Early Evolution of Sauropodomorpha. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(2):e4397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.