Abstract

The richly innervated corneal tissue is one of the most powerful pain generator in the body. Corneal neuropathic pain results from dysfunctional nerves causing perceptions such as burning, stinging, eye-ache and pain. Various inflammatory diseases, neurological diseases, and surgical interventions can be the underlying cause of corneal neuropathic pain. Recent efforts have been made by the scientific community to elucidate the pathophysiology and neurobiology of pain resulting from initially protective physiological reflexes, to a more persistent chronic state. The goal of this clinical review is to briefly summarize the pathophysiology of neuropathic corneal pain, describe how to systematically approach the diagnosis of these patients, and finally summarizing our experience with current therapeutic approaches for the treatment of corneal neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Autologous serum drops, corneal pain, corneal neural anatomy, dry eye, in vivo confocal microscopy, neuropathic pain

INTRODUCTION

Corneal neuropathic disease, corneal neuralgia, or keratoneuralgia is a new and ill-defined disease entity in the field of ophthalmology.1 It has recently generated significant interest amongst both clinicians and scientists due to increasing awareness, and patients surfacing with unexplained ocular surface pain and symptoms.2,3 While the exact epidemiology of this disease remains to be elucidated, increased number of patients present with vague perceptions of burning, stinging, eye-ache, photophobia (photoallodynia)2,4 or severe eye-pain, without significant findings on slit-lamp examination. Currently, the field of Ophthalmology relies on slit-lamp examination to assess signs of corneal and ocular surface diseases. Unfortunately, with neuropathic pain, none to minimal signs can be observed on slit-lamp examination in patients who have been either given the rather broad diagnosis of dry eye disease, or have been repeatedly dismissed by their ophthalmologists. Nevertheless, scientists have in recent years made significant advances and elucidated the pathophysiology and neurobiology of pain resulting from initially protective physiological reflexes, to a more persistent chronic state. The goal of this clinical review is to briefly summarize the pathophysiology of neuropathic corneal pain, create confidence in identifying patients with neuropathic pain, and finally summarizing our experience with current therapeutic approaches for clinicians to better serve these unfortunate patients.

NEURAL BASIS OF PHYSIOLOGICAL OCULAR SURFACE PAIN

Innervation of the Ocular Surface

The human cornea is the most richly innervated tissue in the body.5 Corneal nerves provide an important sensory role by relaying touch, chemical, pain and temperature signals to the brain. In addition, they induce reflex tear production, blinking, and release trophic factors, which help maintain the important structural and functional integrity of the ocular surface.6–9 The blinking and tearing reflex arch is dexterously regulated by the interplay amongst the ocular surface, intact corneal innervation, interconnecting nerves and the lacrimal gland.10 Any compromise in the same, may results in ocular surface damage and disease.

The cornea is also the most powerful pain generator in the body. The estimated central corneal nerve density in humans approximates 7000 nerve terminals per millimeter square and this progressively decreases peripherally.9,11 The presence of the densely innervated non-keratinized corneal epithelium then allows for the detection of minute magnitude nociceptive insults of unparalleled sensitivity, in order to generate defense reflexes, crucial for protection of the ocular surface. Immuno-histochemical staining techniques using both light and electron microscopy have yielded important information about detailed model of the normal human corneal innervation.9 However, studies using these techniques may be unreliable, as nerves degenerate within hours of death.12 Other methods including slit-lamp bio-microscopy, light- and electron microscopy, and in more recent years in vivo confocal microscopy have helped us to better understand the anatomy and distribution of human corneal nerves in health and disease.12–17

Corneal sensory nerves originate mainly from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.18 These travel first in the nasociliary branch, branch into the two long ciliary nerves, before they ultimately rest at equidistant intervals around the limbus. These then enter the cornea as radially directed mid-stromal nerves.14,19–21 While some nerves then terminate as free nerve endings, others form anatomical relationships with stromal keratocytes14 and finally many nerves penetrate the Bowman’s layer to rest under the basal epithelial layer to form the subbasal nerve plexus. Nerves of the subbasal plexus then give rise to superficial intra-epithelial terminals.14 Intra-epithelial fiber terminates as bulbous free nerve endings that contain nociceptors.22 Of note 70–80% of these nerve fibers are unmyelinated C fibers, while the rest are mainly A-δ fibers.23

The Sensory Nervous System

The sensory system consists of sensory receptors, neural pathways, and parts of the brain involved in sensory perception. Sensory neurons transmit sensory information from the peripheral surroundings to the brain and spinal cord.22 The cell bodies of these sensory neurons are located in either the dorsal root ganglia or the trigeminal ganglia. Sensory receptors are grouped into major categories of chemoreceptors (for olfaction), photoreceptors (for vision), mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors, and polymodal receptors. Some others may be silent or sleeping. Of these, mechanoreceptors perceive pressure and distortion and thermoreceptors respond to varying temperatures. Nociceptors are receptors, which result in the perception of pain. Nociceptors are mainly categorized by the various environmental stimuli they respond to which can be mechanical, thermal or chemical in nature.24 Those nociceptors, which can react to more than one of these modalities are labeled as polymodal. Polymodal receptors are activated by near noxious or noxious mechanical, thermal and to a large variety of endogenous chemical stimuli. Many chemical agents such as prostaglandins, bradykinins, capsaicin and acidic environment can excite polymodal nociceptors to evoke impulse discharges in tissues, including the cornea.25 Further, tissue injury and inflammation can cause these polymodal receptors to cause irregular firing at lower thresholds. These receptors are connected centrally to higher-order pain pathways and sensitization to these results in allodynia (pain due to innocuous stimuli), hyperalgesia (enhanced pain perception) and spontaneous pain.25,26 The stimuli received by the receptors are detected and then converted to electrical energy that when reaching a threshold value generates an action potential, which is carried along one or more afferent neurons to the sensory cortex of the brain.

Nociceptive stimulus transduction and somatosensory representation

Nociceptors are free nerve endings that respond to noxious stimuli. Nociceptors are found in skin, organ of motion (periosteum, joint capsule, ligaments, muscles), cornea and dental pulp. The perception of pain begins when nociceptors detect noxious stimuli and via the activation of ion channels transduce the stimulus into electrical energy, inducing action potentials that find their way to the somatosensory cortex and the paralimbic structures where different aspects of pain are deciphered.9,25 From the thalamus, where perception of pain sensation originates, pain then continues its path to the limbic system and the cerebral cortex, where emotional and additional facets of pain are perceived and interpreted.

There are two different types of nociceptor axons—myelinated Aδ fibers with an action potential travel rate of about 20 meters/second and the more slowly conducting unmyelinated C fiber axons that have a speed of around 2 meters/second.26 As a result, pain has an early phase facilitated by the fast-conducting Aδ fibers that can be tremendously sharp and a later segment carried out by the polymodal C fibers that is more prolonged and slightly less intense. Continued input to a C fiber can cause excessive accumulation of action potentials in the spinal cord dorsal horn, thereby resulting in increased sensitivity to pain.27

Peripheral and central sensitization

Sensory neurons are important for the reception, transduction and integration of various stimuli. They have the unique characteristic to exhibit plasticity in the form of sensitization, desensitization or memory.28 Peripheral sensitization signifies a form of functional plasticity of the nociceptor, resulting in change of nociceptors from detectors of noxious stimuli to sensors of non-noxious stimuli. Peripheral axonal injury can result in release of various inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines29, prostaglandins30, substance P31, which can then lower the threshold potentials of ion channels of those specific nerves endings. These changes can then spread to adjacent nociceptors, thereby intensifying peripheral pain signaling. Collectively, these changes provoke alterations in axonal cell bodies, whereby silent receptors become activated and new genes are up-regulated,32,33 thus lowering the threshold to peripheral stimuli, resulting in peripheral sensitization.

Increased peripheral sensitization in turn leads to increased central sensitization over time, when the central neurons become highly responsive to similar magnitude of pain, eventually resulting in heightened awareness of overall pain.34 Increase peripheral activity releases glutamate from presynaptic afferent nerves, triggering sodium channels in the second-order neurons located in the dorsal spinal cord.35 These glutamate receptors can be of 2 types— the AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid) receptors responding only to weak signals, and NMDA (N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid) receptors that respond to strong stimuli. NMDA receptors, when activated, can promote a response that can be intense and long lasting. Stronger nociceptor signals can also activate and cause genotype switching of Aβ fibers, which normally carry sensations of touch.36 The result is hyperalgesia when low power stimuli from regular activity, initiate a painful sensation that lasts longer. Repeated injury or genetic defects can cause allodynia, where an innocent stimulus such as like light touch can cause extreme pain, or photoallodynia where innocuous light stimuli are perceived as extreme pain.

NEUROPATHIC PAIN

The International Association for the Study of Pain recently redefined neuropathic pain as “pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system.37 Long term deregulation in the peripheral nociceptive input can cause malfunctioning of the pain signaling pathway whereby central sensitization can become more autonomous. This is the basis of neuropathic pain, which differs from chronic pain in having an enduring underlying pathology. Damaged neurons and central connections of A-δ and C fibers are the underlying designators for neuropathic pain. Injured neurons may develop micro-neuromata at proximal ends, swelling (endobulbs) at their terminals, and sprouts (neuroma) manifesting regenerative attempts, all of which become sources of ectopic spontaneous pain.38–41 This input is then processed in the CNS, resulting in the classic triad of hyperalgesia, allodynia and spontaneous pain characterizing neuropathic pain.42

Neuropathic Pain of the Cornea

Similar to the pain system elsewhere in the body, corneal nerve endings have various receptors, which have the capability of encoding different mechanical, thermal and chemical stimuli.43 Different types of noxious stimuli activate various populations of sensory fibers to different extent and subsequently illicit different unpleasant sensations. Neuropathic eye pain can be perceived as itch, irritation, dryness, grittiness, burning, aching, and light sensitivity, which are integrated at higher brain centers and are patient specific.44,45 Hyperalgesia and allodynia draw a parallel in the cornea. Hyperalgesia can be perceived as hypersensitivity to moving air, minimal noxious stimuli and to normal light (photoallodynia). Corneal allodynia can be manifested as burning sensation generated by normal non-noxious stimuli, such as wetting drops or even by patient’s own tears.3 Injured corneal nerves (accidental or surgical) have the ability to form neuromas, which though are an attempt to heal, result in abnormal activity and become the source of these unpleasant sensations. Paradoxically, their response to natural stimuli is diminished.46 This can be measured by esthesiometry, which demonstrates low sensitivity in these denervated areas.

Causes of Corneal Neuropathic Pain

Various inflammatory diseases, neurological diseases, or surgical interventions can be the underlying cause of corneal neuropathic pain (Table 1). Some of them include refractive surgery,47 dry eye disease,48,49 Sjögren’s Syndrome,50,51 neuralgia associated with herpes virus,52 benzalkonium chloride (BAK) preserved eye drops, accutane, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy to mention a few.3 Sub-optimally managed severe eye pain is detrimental to both vision related and overall quality of life (QoL). It causes decrease in work performance and can affect aspects of physical, social, and psychological functioning.53,54 Corneal nerve damage may be associated with symptoms of pain, light sensitivity, irritation and sometimes a vague sensation of pressure. Crucial daily activities like reading, driving, and computer work can all be affected in milder disease giving the subject a sense of handicap.54 In more severe cases, this condition is debilitating, resulting in severe photoallodynia requiring dark glasses indoors, decreased autonomy, impaired physical and social function, decreased enjoyment and quality of life, challenges to dignity, threat of increased physical suffering, sleep deprivation, anxiety, depression, and finally existential suffering that may lead to patients seeking active end of life.

Table 1.

Causes of Neuropathic Corneal Pain

| 1. | Dry Eye Disease |

| 2. | Infectious Keratitis |

| 3. | Herpetic keratitis |

| 4. | Recurrent Erosions |

| 5. | Post Surgical (Cataracts, Refractive surgery, Corneal Transplantation) |

| 6. | Chemical Burns |

| 7. | Toxic Keratopathy |

| 8. | Radiation Keratopathy |

| 9. | Miscellaneous: Ocular surface neoplasia, trauma, post-blepharoplasty, iatrogenic trigeminal neuralgia, chronic corneal pain with blepharospasm, fibromyalgia, small fiber neuropathy |

MEASUREMENT AND QUANTIFICATION OF OCULAR SURFACE PAIN

Various questionnaires can help to get an insight into the discomfort experienced by patients. These questionnaires are designed to help practitioners better appreciate the bearing of the condition on everyday life and also to objectively document their findings.55 Most of these are however dry eye questionnaires— the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI),53 The Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL),56 MacMonnies Dry Eye Questionnaire,57 Subjective Evaluation of Symptom of Dryness and the Standard patient evaluation of eye dryness (SPEED) questionnaires.58 These questionnaires ask for symptoms, frequency of symptoms, severity of symptoms, use of medications etc. These surveys use a numerical scale and thus make recording symptoms easy for patients and clinicians. However, current questionnaires for eye pain are subjective and invalidated. The 2010 NEI Workshop on Ocular Pain & Sensitivity identified and highlighted the need for validated quantitative tools to assess, measure and quantify ocular pain.59 To meet these needs, our group has recently designed and validated a hybrid eye pain questionnaire, the Ocular Pain Assessment Survey (OPAS) that helps evaluate corneal and ocular surface pain, and its impact on QoL.60 The OPAS seems to have high reliability and demonstrates significant decline in QoL and associated symptoms with improvement in corneal pain.

ASSESSMENT OF OCULAR SURFACE PAIN

Indirect Measures

Several clinical methods can be used to test the function of corneal nerves. Slit-lamp examination with various vital dyes, such as fluorescein, rose bengal and lissamine green reveal the general health of the ocular surface. While fluorescein can help to identify corneal epithelial breakdown, lissamine green helps to stain the devitalized cornea and conjunctival surface. Other indirect tests used most often in clinical practice include Schirmer’s and phenol red tests to evaluate tear production and state of lacrimal system function. Tear film osmolarity and tear film break-up time are other useful adjuncts to assess or screen for dry eye disease. Various osmometers are available commercially and in general, tear film osmolarity less that 290 mOsmol/L is thought to be normal, with values above 316 mOsmol/L being highly suggestive of dry eye disease.61 However, significant overlap exists between normal subjects and patients with dry eye disease and increased variability in these patients may affect measured outcomes.61

Direct measures

Direct measures use various esthesiometers, such as the Cochet-Bonnet contact esthesiometer, which can detect mechanical nociceptor responses, thereby quantifying Aδ fibers function. Further, the non-contact Belmonte ethesiometer is capable of detecting polymodal functionality of both Aδ and C fibers and may be more informative.62

Peripheral vs. Central Neuropathic Pain —The Proparacaine Challenge Test

Some basic tests may aid in distinguishing between peripheral and central pain, although many patients may suffer from a combination of both. The proparacaine challenge with instillation of a drop topical anesthesia of 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride (Alcaine, Alcon) on the ocular surface will attenuate peripheral, but not central pain. Measures, such as the use of soft contact lenses and moisture goggles may also help to neutralize the evaporative component of the tears and will decrease peripheral but not central pain. Patients with no relief from any of the above measures likely suffer, at least in part, from central neuropathic pain. Likewise those who have some relief with the proparacaine challenge, likely suffer from combined peripheral and central neuropathic pain.

In Vivo Confocal Microscopy

Patients with neuropathy benefit from referral to a cornea specialist at a tertiary care center with facilities for in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM). IVCM is a noninvasive procedure that allows imaging of the cornea at the cellular level.63 IVCM allows the study of corneal cells, nerves and the immune cells and their various interactions in ocular and systemic diseases.16,64 IVCM has been utilized to study nerve changes in various conditions including normal eyes, keratoconus, dry eye disease,65 contact lens wear, neurotrophic keratopathy,66 infectious keratitis,67 post refractive surgery, among others.16,63,64,68 Moreover, IVCM has enabled us to study the regenerative changes of the corneal nerves and correlation with corneal sensation.6,64,69 Studies have shown varying degrees of reduced nerve fiber density, increased sub-basal nerve tortuosity, increase in nerve fiber beading, branching, reflectivity, neuromas and nerve sprouting.70–72 Beadlike formations are thought to be metabolically active transmitter-containing nerve fibers, which are likely an effort to improve the abnormal epithelial trophism.73 Alternatively, they are thought to represent nerve damage resulting in secretion of nerve growth factors.74 A baseline IVCM in patients with neuropathic pain can help assess and confirm nerve abnormalities like neuromas, increased nerve tortuosity, increased beading, decreased density of nerve fibers and increase in dendritic cells, which can be subsequently followed by post-treatment IVCM to monitor for changes and reversal of baseline findings.4 In a recent study, our groups demonstrate that patients with corneal neuropathy-induced photoallodynia demonstrate profound alterations in the subbasal corneal nerves including increased reflectivity, beading and neuromas. Further, we demonstrated that autologous serum tears helped restore nerve topography through nerve regeneration, and this correlated with improvement in patient-reported photoallodynia.4

APPROACH TO MANAGEMENT OF NEUROPATHIC CORNEAL PAIN

Nerve injury results may result in the release of inflammatory cytokines from both the injured and healthy nerves.50,63 Intuitively, therapeutic strategies proposed to decrease inflammation and induce nerve regeneration form the rationale behind use of these agents for the treatment of neuropathic corneal pain.17 Various studies and anecdotal evidence have emerged suggesting that biological factors, including nerve growth factor (NGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), pigment epithelial growth factor (PEDF), docosahexenoic acid (DHA), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating protein (PACAP), and interleukin-17 (IL-17), as well as cells such as T lymphocytes, may result in nerve regeneration.17,75–78 Others, like cyclosporine and corticosteroids have a mixed action, and still others like BAK are purely neurotoxic.78–80 Steroids decrease many aspects of the inflammatory response by inhibiting transcription factors which activate pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cyclosporine acts as an anti-inflammatory agent by decreasing lymphocytes and other pro-inflammatory cytokines in the conjunctiva.79 NGF helps in regeneration, remodulation and restoration of the function of the nerves.76 Similarly, autologous serum tear drops supply the eye with several epithelial and nerve growth factors, including vitamin A, epidermal growth factor, and fibronectin and have shown to be helpful in nerve regeneration.4 However, a multi-step approach is required in the treatment of corneal neuropathic pain (Table 2). Many of the therapies discussed below for neuropathic cornealpain are derived from evidence-based literature for non-corneal neuropathic pain. Their used for corneal neuropathic pain comes from longstanding personal experience of the authors and need to be tested in larger randomized trials. The authors approach this by a three-step process of managing surface disease, managing co-morbidities, and finally managing the true component of pain, which itself encompasses regenerative, anti-inflammatory and environmental modifiers.

Table 2.

Management of Neuropathic Corneal Pain

|

A. Treatment of ocular surface disease 1. Increase Tear production - Use PFATs 2. Increase Tear Retention - Punctal plugs, contact lenses, moisture goggles 3. Treatment of lids and ocular surface disease - Treat blepharitis with lid hygiene, warm compresses - Refractory cases: Meibomian Gland Probing, Lipiflow, Intense Pulse Lighted Therapy 4. Managing comorbid conditions - Treat allergies, conjunctival chalasis, lagophthalmos and nocturnal exposure |

|

B. Anti-inflammatory agents 1. Topical corticosteroids 2. Topical and oral Azithromycin, oral doxycycline 3. Cyclosporine 4. Tacrolimus 5. Anakinra |

|

C. Regenerative Therapy 1. Autologous serum eye drops (20–100%) 2. Nerve growth factor 3. Platelet rich plasma 4. Umbilical cord serum eye drops |

|

D. Protect ocular surface when required 1. Bandage contact lenses 2. Scleral Contact Lenses (e.g., PROSE) |

|

E. Systemic Pharmacotherapy for Pain 1.TCAs like Nortriptyline, amitryptilline 2. Carbamazepine 3. GABAergic drugs (gabapentin, pregabalin) 4. SNRI like duloxetine and venlafaxine 5. Opioids like Tramadol 6. Class 1B sodium channel blocker Mexiletine |

|

F. Complementary and alternative measures 1. Acupuncture 2. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation 3. Scrambler Therapy 4. Implantable neuromodulators 4. Cardio- Exercise 5. Omega-3 rich diet |

PFAT’s: preservative free artificial tears, PROSE: Prosthetic Replacement of the Ocular Surface Ecosystem; TCAs: tricyclic anti-depressants; SNRI: serotonin- nor epinephrine reuptake inhibitors

A. Treatment of ocular surface disease

Treatment should begin with palliative care- no matter the underlying pathology of dry eye or neuralgia, lubricating the surface with modest frequency of non-preserved artificial tears or emulsion-based tears may be beneficial. Often, a mixed component of aqueous deficient and evaporative types of dry eye disease is present. Lubricants may dilute inflammatory mediators, decrease tear film hyper-osmolality and also help in better spread of the lipid layer of tears. The addition of punctal plugs to maintain a more generous tear lake in the absence of inflammation can be of benefit to some patients. Care must be taken, however, not to place plugs in eyes with active allergies and inflammation, as this may increase the contact time of the allergens on the surface or induce increased pain by trapping inflammation. Moisture chamber goggles increase moisture and prevent evaporation at the ocular surface. Topical lipid supplements like castor oil or mineral oil and emulsion based lubricants improve the stability of tear film. The authors recommend treating any concomitant posterior blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction with hot compresses and lid massage or medical therapy (Table 2). For cases refractory to medical management, procedures such as intraductal meibomian gland probing, thermal pulsation devices (Lipiflow), and intense pulse lighted therapy may aid in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction and subsequent increase of TBUT.81 Patients with neuropathic pain may however show improvement of ocular surface signs, but exhibit partial, mild, or no improvement in symptoms after prolonged treatment with the above outlined treatments.

B. Anti-inflammatory agents

Patients with corneal neuropathic pain typically require chronic use of anti-inflammatory agents (Table 2) for relief of symptoms, to decrease the inflammatory milieu and break the cycle of chronic inflammation, and prevent recurrent episodes. Inflammation may not always be visible on slit-lamp examination and IVCM may aid in the assessment of subclinical inflammation.64 Steroids are the main stay of treatment, especially for initial rapid relief. The authors prefer loteprednol 0.5% at an initial qid dose with bi-weekly taper to once or twice a week over a 6–8 week period. Further, Cyclosporine A (CSA) is a well-known anti-inflammatory agent that modulated the T cells and works by reducing ocular surface inflammation and increasing tear production in dry eye disease.82 However, CSA has been shown in a preclinical study to potentially retard nerve fiber regeneration due to loss of pro-neural IL-6 signaling.79 Nevertheless, the use CSA in aqueous deficient patients may be of value by increasing tear volume.

Studies have shown that interleukin 1 (IL-1) by promoting activating and migration of leukocytes is closely involved in the regulation of ocular surface inflammation.83 Anakinra (Kineret) is a human IL-1 receptor antagonist and has showed efficacy in reducing corneal surface inflammation and epitheliopathy.83 The authors use Kineret 2.5% at TID dosing for 3–6 months in patients refractory to above treatment. Similarly, Tacrolimus, which is a calcineurin inhibitor like cyclosporine acts as an immunosuppressive agent and has been found to be a useful anti-inflammatory agent when used topically at a concentration of 0.03% at bid dosing for 3–6 months.84 Topical azithromycin is being potentially effective and well-tolerated therapy of lid margin disease and meibomian gland dysfunction.85,86 It is anti-inflammatory, inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines, and is effective against gram-negative micro-organisms. It remains at therapeutic levels on the ocular surface days after stopping therapy.

Oral drug therapy may be useful in many cases. Doxycycline is an antimicrobial and inhibits matrix metalloproteinases that degrade connective tissue.87 It has earned valuable use in treatment of ocular rosacea and increasing tear film stability. Oral doxycycline at a dose of 100 mg once or twice a day for 2–3 months followed by daily dosing for another 3 months seems to be very helpful. In addition, topical antibiotics like azithromycin 1% have immuno-modulatory and anti-inflammatory properties and application to lids at bedtime improves symptoms in many patients.

C. Nerve Regenerative Therapy

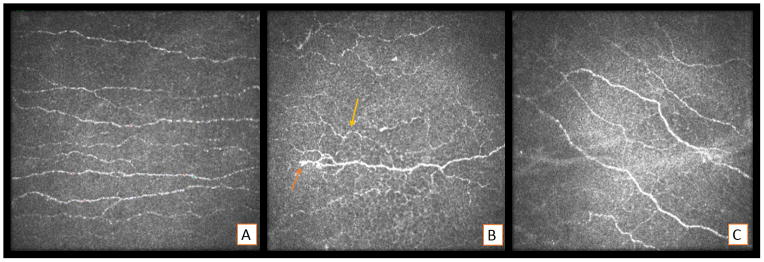

Autologous serum eye drops contain a variety of pro-epithelial and pro-neural factors like epidermal growth factor (EGF), NGF, insulin like growth factor (IGF-1) etc.4,88 Concentrations from 20–100% have been shown to encourage epithelial healing, increase nerve density, decrease nerve tortuosity.4 In this first evidence based study for treatment of corneal neuropathic pain, IVCM demonstrated significantly improved nerve parameters including total nerve length, number, reflectivity and also reduction of beading and neuromas in patients treated with autologous serum tears.4 However, inflammation may play a key role in peripheral nerve degeneration.89 Recent studies with the help of IVCM have shown a substantial correlation between the increase in dendritic cell numbers and decreased sub-basal corneal nerves signifying a possible interaction between the immune and nervous system in the cornea.63 Clinical experience is compelling for concurrent use of low dose steroids with autologous serum eye drops for successful regeneration of corneal nerves.90 In our experience, the combination of low dose immunosuppressive therapy together with the use of autologous serum tears seems to be greatly beneficial (Figure 1) as steroids promote to decrease the initial inflammatory load of the ocular surface, preventing flares and thus likely allowing for undisturbed neuronal regeneration. However, it is now recognized that some quantity of IL-17 and VEGF-A are necessary for efficient nerve regeneration.75 Although this suggests that minor degree of inflammation may trigger a milieu for corneal nerve regeneration, excessive inflammation may lead to loss of corneal innervation. In the aggregate and in our experience, limiting inflammation at the initiation of therapy, is crucial in successful therapy of patients with neuropathic corneal pain.

Figure 1.

Representative in vivo confocal microscopic pictures A) Normal cornea of a patient showing subbasal plexus of nerves. B) Patient with corneal pain showing decrease in nerve density, increased tortuosity (yellow arrow) and beading (orange arrow). C) Same patient exhibiting increase in nerve density, less tortuosity and disappearance of beading 8 weeks of lotemax and autologous serum tears treatment.

Though not commercially available in the United States, umbilical cord serum eye drops, platelet-rich plasma and NGF seem to show promising results in treating dry eye syndrome, neurotrophic keratitis and result in nerve regeneration.91–94 Platelets contain many bioactive compounds like platelet derived growth factor, active metabolites, VEGF, and TGF-β, which have been shown to help in nerve regeneration in experimental models.92 Clinical studies have shown that autologous plasma use is capable of nerve regeneration in patients of neurotrophic keratopathy.95

D. Protective Contact Lenses

When topical pharmacotherapy fails to provide adequate relief, the authors recommend a trial of extended wear soft bandage contact lenses to accelerate resurfacing of the corneal surface. A regular bandage contact lens may particularly be effective in cases of recurrent corneal abrasions. However, the underlying dry ocular surface, increased risk of infections with prolonged wear make them less attractive options. Shielding the sensitized corneal receptors from the triggering environmental stimulus forms the rationale behind the use of scleral lenses. The most effective lens in maintaining the pre-corneal nociceptive barrier is the liquid corneal bandage created by the fluid filled scleral lenses like PROSE (Prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem, Boston Foundation for Sight).96,97 It is felt that treating corneal epitheliopathy timely in the disease process may help to reverse chronic pain. However, once established the corneal bandage by itself is usually not adequate. Moreover, given that patients may suffer from concurrent hyperalgesia, placement of contact lenses on the ocular surface may be a strong noxious stimulus in this cohort.

E. Systemic Pharmacotherapy for Pain

Despite these measures, the pain-generating nerves can still fire spontaneously and thus may need to be targeted directly. Corneal pain can result from peripheral and/or central sensitization. Pharmacotherapy used for pain management may provide significant relief, in particular in patients with a central component of neuropathic pain.98–104 Data on the use of systemic pharmacotherapy for corneal neuropathic pain is however scarce. Various options are available that include anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine), tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. Nortriptyline), serotonin uptake inhibitors, opioids etc. No randomized studies have been performed to date to study their usage in corneal neuropathic pain, but their use can be extrapolated from treatment of neuropathic pain elsewhere.99 Gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the key inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system.100 Drugs like gabapentin (Neurontin) and pregabalin (Lyrica) that were first developed and used as anticonvulsants, are now endorsed as first line agents for the treatment of neuropathic pain arising from diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and central neuropathic pain.101 These drugs binding to the α-2-delta subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels, causing decrease in the inflow of calcium into the neurons thus stabilizing them throughout the central nervous system.102 Gabapentin therapy can be initiated on day 1 as a single 600 mg dose, on day 2 as 1200 mg/day and on day 3 as 1800 mg/day. Patients are instructed to subsequently titrate the dose up as needed for pain relief to a maximum dose of 3600 mg/day (900 mg four times a day). The most common dose-limiting side effects include sedation, somnolence and dizziness and can often be judicially fared by a slow titration of the dose.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are a class of drugs that exert effect by inhibiting presynaptic reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine and by blocking cholinergic, adrenergic, histaminergic, and sodium channels. Drugs like amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine, and imipramine are classified as TCAs. The Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) recommends secondary amine TCAs like nortriptyline and desipramine as first-line treatment choice for neuropathic pain. It recommends use of tertiary amines like amitriptyline and imipramine only if a secondary amine is not accessible.103 The TCAs are initially given at a dose of 10 to 25 mg nightly. Depending on the response and tolerance, this can be titrated by 10 to 25 mg every 3 to 7 days up to a maximum of 150 mg nightly. Patients need to be educated and warned about the anticholinergic side effects, which are frequent and may be dose limiting. Some of these include dry mouth and eyes, excess sedation, urinary retention, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, and blurry vision. Again, these can be minimized by starting at a lower dose and slowly titratation.103 Serotonin-norepinephrine inhibitors like Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (Effexor) have also been studied for the treatment of neuropathic pain.101,103 While we recommend that one agent at a time be tried in patient with corneal neuropathic pain, combination therapy is often required in refractory cases.

Carbamazepine is a class of anti-epileptic drug that has been used for trigeminal neuralgia. Relief of corneal pain may be achieved at low doses, but the usual effective dose ranges from 800 to 1600 mg divided in two to four doses per day. Once response has been achieved it can be tapered to a minimal effective dose. Another class of drugs validated for the treatment of neuropathic pain by randomized controlled trials are opioids, such as Tramadol. It binds to the μ-opioid receptor and inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine and has been found to be effective in moderate to severe pain. Again side effects such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, sedation, and dependence, limits their use opioids as second-line medications, when the first-line medications fail to achieve a satisfactory response. In cases where immediate and short-term relief for acute neuropathic pain is desired, they may be justified as first-line use.101,103 When the above drugs are ineffective or not well tolerated, Mexiletine can serve as an alternative second line therapy.104 Mexiletine (225 to 675 mg/day) is an orally active local anesthetic agent, which is structurally related to lidocaine and has been used to alleviate neuropathic pain of various origins.104 Side effects like nausea, sleep disturbance, headache, shakiness, dizziness and tiredness may however limit its prolonged use.

F. Complementary and alternative medical approaches

Numerous mechanisms involved in generating pain explains why single treatments may not be effective. Some patients, despite use of all the above measures in various combinations, still do not achieve adequate pain relief. The authors have found that use of adjunctive therapies, such as acupuncture and vigorous exercise may provide temporary relief and/or decrease the need for pharmacotherapy in many patients. There is increasing evidence that acupuncture stimulates endogenous opioid mechanisms, may stimulate gene expression of neuropeptides and if safely done may be a traditional pain management treatment contributing to modern medicine.105 Many of our patients report getting the extra relief ranging between a few hours to a few days that could not have been achieved by following the algorithm for modern medicine.

Patients that have been refractory to all above treatment could be referred for a trial of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) or Scrambler Therapy. TMS is a noninvasive method to cause depolarization or hyperpolarization in the neurons of the brain. It is being agreed upon that where evidence based medicine is failing to treat neuropathic pain, high-frequency repetitive TMS (rTMS) of those brain regions which parallel the body parts in pain may be effective.106 A meta-analysis gaging the analgesic effect of rTMS on various neuropathic pain states proposes rTMS to be more effective in suppressing central than peripheral neuropathic pain.107 Another useful therapy used to control chronic neuropathic pain is Scrambler therapy. The Scrambler Therapy works on the principle of interfering with pain signal transmission, by mixing a non-pain information with the pain signal into the nerve fibers and thus confusing the nervous system ability to sense pain.108 Increasing number of studies are reporting that Scrambler therapy may give relief from chronic neuropathic pain due to various underlying etiologies more successfully than the previous outlined drugs.109 Neuromodulation is an intervention that involves stimulation or administration of medications directly to the body’s nervous system for therapeutic purposes. It involves implantable as well as non-implantable devices that deliver electrical, chemical or other agents to reversibly modify brain and nerve cell activity. Neuromodulation therapies allow focused delivery of modifying agents – e.g. electrical, optical or chemical signals - to targeted areas of the nervous system in order to improve neural function.110

Recent evidence from both animal and human studies suggests that cardio-exercise by inhibiting pain pathways may alter the perception of pain experience centrally. Exercise may help to increase the brain neurotrophic factors and thus contribute to neuroplasticity and neuro-restoration.111,112 We therefore recommend that our patients be involved in some kind of cardio-exercise for about 30–45 minutes at least 3–5 times a week. Nutritional intervention strategies like increasing the ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids has been shown to regulate inflammation in the body and this knowledge can be exploited to optimize health in pain patients also.113 Foods like flaxseed oil, fish oil, walnuts, soybeans are rich in omega-3 fatty acids. We recommend that our patients be on 1000 mg bid to tid daily dosing of either fish oil or flaxseed oil. Presence of allergies, conditions like conjunctival chalasis, lagophthalmos and nocturnal exposure should be carefully assessed and addressed appropriately medically or surgically Gluten sensitivity may be etiologically linked to a substantial number of idiopathic axonal neuropathies.114 Gluten seems to cause and support neuronal inflammation, and in our experience change to gluten-free diet has resulted in variable decrease in neuropathic corneal pain. We recommend our patients to be tested for gluten sensitivity and if tested positive abstain from gluten products.

CONCLUSIONS

Neuropathic corneal pain in itself results from a complex interplay of various central and peripheral mechanisms. Currently, our knowledge and appreciation of the pathophysiology of corneal pain is in its early stages. Most of the above-mentioned pain treatments in ophthalmology have been borrowed from other areas of medicine. The complexities of these pathways have yet to be unfolded. No single therapeutic approach or drug is satisfactory currently. Awareness over the past few years that corneal pain is real has been a step in the right direction. However, much work has to be done to assess therapeutic approaches for this patients suffering from a debilitating disease. Working together with other disciplines of both conventional (e.g. neurology and rheumatology) and alternative medicine may be the best current approach to be followed.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: NIH R01-EY022695 (PH), Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (PH), Falk Medical Research Trust (PH).

The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Financial interest: None

References

- 1.Belmonte C. Eye dryness sensations after refractive surgery: impaired tear secretion or “phantom” cornea? J Refract Surg. 2007;23(6):598–602. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20070601-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenthal P, Borsook D. The corneal pain system. Part I: the missing piece of the dry eye puzzle. Ocul Surf. 2012;10(1):2–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal P, Baran I, Jacobs DS. Corneal pain without stain: is it real? Ocul Surf. 2009;7(1):28–40. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal S, Kheirkhah A, Cavalcanti BM, et al. Autologous Serum Tears for Treatment of Photoallodynia in Patients with Corneal Neuropathy: Efficacy and Evaluation with In Vivo Confocal Microscopy. Ocul Surf. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2015.01.005. pii: S1542–0124(15)00009–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beuerman RW, Tanelian DL. Corneal pain evoked by thermal stimulation. Pain. 1979;7(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(79)90102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beuerman RW, Schimmelpfennig B. Sensory denervation of the rabbit cornea affects epithelial properties. Exp Neurol. 1980;69(1):196–201. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(80)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toivanen M, Tervo T, Partanen M, et al. Histochemical demonstration of adrenergic nerves in the stroma of human cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28(2):398–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishida T. Neurotrophic mediators and corneal wound healing. Ocul Surf. 2005;3(4):194–202. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller LJ, Marfurt CF, Kruse F, Tervo TM. Corneal nerves: structure, contents and function. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76(5):521–42. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern ME, Gao J, Siemasko KF, et al. The role of the lacrimal functional unit in the pathophysiology of dry eye. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78(3):409–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millodot M. A review of research on the sensitivity of the cornea. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1984;4(4):305–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller LJ, Vrensen GF, Pels L, et al. Architecture of human corneal nerves. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(5):985–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller LJ, Pels L, Vrensen GF. Ultrastructural organization of human corneal nerves. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(4):476–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marfurt CF, Cox J, Deek S, Dvorscak L. Anatomy of the human corneal innervation. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90(4):478–92. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel DV, McGhee CN. In vivo confocal microscopy of human corneal nerves in health, in ocular and systemic disease, and following corneal surgery: a review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(7):853–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruzat A, Pavan-Langston D, Hamrah P. In vivo confocal microscopy of corneal nerves: analysis and clinical correlation. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(5–6):171–7. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2010.518133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaheen BS, Bakir M, Jain S. Corneal nerves in health and disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59(3):263–85. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marfurt CF, Kingsley RE, Echtenkamp SE. Sensory and sympathetic innervation of the mammalian cornea. A retrograde tracing study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30(3):461–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zander E, Weddell G. Observations on the innervation of the cornea. J Anat. 1951;85(1):68–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Aqaba MA, Fares U, Suleman H, et al. Architecture and distribution of human corneal nerves. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(6):784–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.173799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He J, Bazan NG, Bazan HE. Mapping the entire human corneal nerve architecture. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91(4):513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruger L, Light AR, Schweizer FE. Axonal terminals of sensory neurons and their morphological diversity. J Neurocytol. 2003;32(3):205–16. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000010080.62031.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belmonte C, Perez E, Lopez-Briones LG, Gallar J. Chronic stimulation of ocular sympathetic fibers in unanesthetized rabbits. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28(1):194–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee Y, Lee CH, Oh U. Painful channels in sensory neurons. Mol Cells. 2005;20(3):315–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks J, Tracey I. From nociception to pain perception: imaging the spinal and supraspinal pathways. J Anat. 2005;207(1):19–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reichling DB, Levine JD. Critical role of nociceptor plasticity in chronic pain. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32(12):611–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baron R. Neuropathic pain: a clinical perspective. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;(194):3–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hucho T, Levine JD. Signaling pathways in sensitization: toward a nociceptor cell biology. Neuron. 2007;55(3):365–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oprée A, Kress M. Involvement of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL-1 beta, and IL-6 but not IL-8 in the development of heat hyperalgesia: effects on heat-evoked calcitonin gene-related peptide release from rat skin. J Neurosci. 2000;20(16):6289–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06289.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CR, Amaya F, Barrett L, et al. Prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319(3):1096–103. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor TM, O’Connell J, O’Brien DI, et al. The role of substance P in inflammatory disease. J Cell Physiol. 2004;201(2):167–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ji RR. Peripheral and central mechanisms of inflammatory pain, with emphasis on MAP kinases. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2004;3(3):299–303. doi: 10.2174/1568010043343804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heppelmann B, Messlinger K, Schaible HG, Schmidt RF. Nociception and pain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1991;1(2):192–7. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(91)90077-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hains BC, Saab CY, Klein JP, et al. Altered sodium channel expression in second-order spinal sensory neurons contributes to pain after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24(20):4832–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0300-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhave G, Gereau RW., 4th Posttranslational mechanisms of peripheral sensitization. J Neurobiol. 2004;61(1):88–106. doi: 10.1002/neu.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacIver MB, Tanelian DL. Structural and functional specialization of A delta and C fiber free nerve endings innervating rabbit corneal epithelium. J Neurosci. 1993;13(10):4511–24. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04511.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, et al. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;152(10):2204–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oaklander AL. The density of remaining nerve endings in human skin with and without postherpetic neuralgia after shingles. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):139–45. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wall PD, Gutnick M. Properties of afferent nerve impulses originating from a neuroma. Nature. 1974;248(5451):740–3. doi: 10.1038/248740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wall PD, Gutnick M. Ongoing activity in peripheral nerves: the physiology and pharmacology of impulses originating from a neuroma. Exp Neurol. 1974;43(3):580–93. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(74)90197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han HC, Lee DH, Chung JM. Characteristics of ectopic discharges in a rat neuropathic pain model. Pain. 2000;84(2–3):253–61. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flor H. Phantom-limb pain: characteristics, causes, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1(3):182–9. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acosta MC, Tan ME, Belmonte C, Gallar J. Sensations evoked by selective mechanical, chemical, and thermal stimulation of the conjunctiva and cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(9):2063–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng Y, Simpson TL. Nociceptive sensation and sensitivity evoked from human cornea and conjunctiva stimulated by CO2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(2):529–32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng Y, Simpson TL. Characteristics of human corneal psychophysical channels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(9):3005–10. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Belmonte C, Aracil A, Acosta MC, et al. Nerves and sensations from the eye surface. Ocul Surf. 2004;2(4):248–53. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toda I, Asano-Kato N, Komai-Hori Y, Tsubota K. Dry eye after laser in situ keratomileusis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00959-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stern ME, Beuerman RW, Fox RI, et al. The pathology of dry eye: the interaction between the ocular surface and lacrimal glands. Cornea. 1998;17(6):584–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199811000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solomon A, Dursun D, Liu Z, et al. Pro- and anti-inflammatory forms of interleukin-1 in the tear fluid and conjunctiva of patients with dry-eye disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(10):2283–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gøransson LG, Herigstad A, Tjensvoll AB, et al. Peripheral neuropathy in primary sjogren syndrome: a population-based study. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(11):1612–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barendregt PJ, van den Bent MJ, van Raaij-van den Aarssen VJ, et al. Involvement of the peripheral nervous system in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(9):876–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liesegang TJ. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus natural history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and morbidity. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(2 Suppl):S3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Friedman NJ. Impact of dry eye disease and treatment on quality of life. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(4):310–6. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833a8c15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miljanović B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, Schaumberg DA. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(3):409–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grubbs JR, Jr, Tolleson-Rinehart S, Huynh K, Davis RM. A review of quality of life measures in dry eye questionnaires. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21(4):310–6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, Mertzanis P, et al. Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) Study Group. Development and validation of the impact of dry eye on everyday life (IDEEL) questionnaire, a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of the burden of dry eye on patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gothwal VK, Pesudovs K, Wright TA, McMonnies CW. McMonnies questionnaire: enhancing screening for dry eye syndromes with Rasch analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(3):1401–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ngo W, Situ P, Keir N, et al. Psychometric properties and validation of the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaire. Cornea. 2013;32(9):1204–10. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318294b0c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nelson JD, Shimazaki J, Benitez-del-Castillo JM, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(4):1930–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6997b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamrah P, Qazi Y, Hurwitz S, et al. Impact of Corneal Pain on Quality of Life (QoL): The Ocular Pain Assessment Survey (OPAS) Study. ARVO abstract. 2014 P#1469. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bunya VY, Fuerst NM, Pistilli M, et al. Variability of Tear Osmolarity in Patients With Dry Eye. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015:26. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.0429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy PJ, Patel S, Kong N, et al. Noninvasive assessment of corneal sensitivity in young and elderly diabetic and nondiabetic subjects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(6):1737–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cruzat A, Witkin D, Baniasadi N, et al. Inflammation and the nervous system: the connection in the cornea in patients with infectious keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(8):5136–43. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mantopoulos D, Cruzat A, Hamrah P. In vivo imaging of corneal inflammation: new tools for clinical practice and research. Semin Ophthalmol. 2010;25(5–6):178–85. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2010.518542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alhatem A, Cavalcanti B, Hamrah P. In vivo confocal microscopy in dry eye disease and related conditions. Semin Ophthalmol. 2012;27(5–6):138–48. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2012.711416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Unilateral herpes zoster ophthalmicus results in bilateral corneal nerve alteration: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(1):40–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(10):1930–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hamrah P, Sahin A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Cellular changes of the corneal epithelium and stroma in herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(9):1791–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Patel DV, McGhee CN. In vivo confocal microscopy of human corneal nerves in health, in ocular and systemic disease, and following corneal surgery: a review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(7):853–60. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tervo TM, Moilanen JA, Rosenberg ME, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy for studying corneal diseases and conditions associated with corneal nerve damage. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;506(Pt A):657–65. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0717-8_92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rosenberg ME, Tervo TM, Müller LJ, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy after herpes keratitis. Cornea. 2002;21(3):265–9. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200204000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Labbé A, Alalwani H, Van Went C, et al. The relationship between subbasal nerve morphology and corneal sensation in ocular surface disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(8):4926–31. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tuisku IS, Konttinen YT, Konttinen LM, Tervo TM. Alterations in corneal sensitivity and nerve morphology in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86(6):879–85. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Villani E, Galimberti D, Viola F, et al. The cornea in Sjogren’s syndrome: an in vivo confocal study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(5):2017–22. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Z, Burns AR, Han L, et al. IL-17 and VEGF are necessary for efficient corneal nerve regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(3):1106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Esquenazi S, Bazan HE, Bui V, et al. Topical combination of NGF and DHA increases rabbit corneal nerve regeneration after photorefractive keratectomy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(9):3121–7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.He J, Cortina MS, Kakazu A, Bazan HE. The PEDF Neuroprotective Domain Plus DHA Induces Corneal Nerve Regeneration After Experimental Surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(6):3505–13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sarkar J, Chaudhary S, Namavari A, et al. Corneal neurotoxicity due to topical benzalkonium chloride. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):1792–802. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Namavari A, Chaudhary S, Chang JH, et al. Cyclosporine immunomodulation retards regeneration of surgically transected corneal nerves. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(2):732–40. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pan S, Li L, Xu Z, Zhao J. Effect of leukemia inhibitory factor on corneal nerve regeneration of rabbit eyes after laser in situ keratomileusis. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499(2):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Qiao J, Yan X. Emerging treatment options for meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1797–803. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S33182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Donnenfeld E, Pflugfelder SC. Topical ophthalmic cyclosporine: pharmacology and clinical uses. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54(3):321–38. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Amparo F, Dastjerdi MH, Okanobo A, et al. Topical interleukin 1 receptor antagonist for treatment of dry eye disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(6):715–23. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moscovici BK, Holzchuh R, Sakassegawa-Naves FE, et al. Treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome dry eye using 0.03% tacrolimus eye drop: Prospective double-blind randomized study. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2015.04.004. pii: S1367-0484(15)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.John T, Shah AA. Use of azithromycin ophthalmic solution in the treatment of chronic mixed anterior blepharitis. Ann Ophthalmol (Skokie) 2008;40:68–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Foulks GN, Borchman D, Yappert M, Kakar S. Topical azithromycin and oral doxycycline therapy of meibomian gland dysfunction: a comparative clinical and spectroscopic pilot study. Cornea. 2013;32(1):44–53. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318254205f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Golub LM, Lee HM, Ryan ME, et al. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown by multiple non-antimicrobial mechanisms. Adv Dent Res. 1998;12:12–26. doi: 10.1177/08959374980120010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yoon KC, Heo H, Im SK, et al. Comparison of autologous serum and umbilical cord serum eye drops for dry eye syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(1):86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Benowitz LI, Popovich PG. Inflammation and axon regeneration. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(6):577–83. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834c208d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Outcome of Autologous Serum Tears with Concurrent Anti-inflammatory Treatment in Ocular Surface Disease. ARVO. abstract 2013-P#314. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoon KC, Heo H, Jeong IY, Park YG. Therapeutic effect of umbilical cord serum eyedrops for persistent corneal epithelial defect. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2005;19(3):174–8. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2005.19.3.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2259–72. doi: 10.1177/0363546509349921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aloe L, Tirassa P, Lambiase A. The topical application of nerve growth factor as a pharmacological tool for human corneal and skin ulcers. Pharmacol Res. 2008;57(4):253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Di Fausto V, Fiore M, Tirassa P, et al. Eye drop NGF administration promotes the recovery of chemically injured cholinergic neurons of adult mouse forebrain. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26(9):2473–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rao K, Leveque C, Pflugfelder SC. Corneal nerve regeneration in neurotrophic keratopathy following autologous plasma therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(5):584–91. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.164780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Stason WB, Razavi M, Jacobs DS, et al. Clinical benefits of the Boston Ocular Surface Prosthesis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jacobs DS, Rosenthal P. Boston scleral lens prosthetic device for treatment of severe dry eye in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Cornea. 2007;26(10):1195–9. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318155743d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Acosta MC, Berenguer-Ruiz L, García-Gálvez A, et al. Changes in mechanical, chemical, and thermal sensitivity of the cornea after topical application of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(1):282–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, et al. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence based proposal. Pain. 2005;118(3):289–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hirata H, Okamoto K, Bereiter DA. GABA (A) receptor activation modulates corneal unit activity in rostral and caudal portions of trigeminal subnucleus caudalis. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90(5):2837–49. doi: 10.1152/jn.00544.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, et al. European Federation of Neurological Societies. EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(9):1113–e88. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jensen TS, Madsen CS, Finnerup NB. Pharmacology and treatment of neuropathic pains. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(5):467–74. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283311e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Kent J, et al. International Association for the Study of Pain Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain. 2013;154(11):2249–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Carroll IR, Kaplan KM, Mackey SC. Mexiletine therapy for chronic pain: survival analysis identifies factors predicting clinical success. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(3):321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):374–83. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lefaucheur JP, André-Obadia N, Antal A, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) Clin Neurophysiol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.021. pii: S1388-2457(14)00296-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leung A, Donohue M, Xu R, et al. rTMS for suppressing neuropathic pain: a meta-analysis. J Pain. 2009;10(12):1205–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sabato AF, Marineo G, Gatti A. Scrambler therapy. Minerva Anestesiol. 2005;71(7–8):479–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marineo G, Iorno V, Gandini C, et al. Scrambler therapy may relieve chronic neuropathic pain more effectively than guideline-based drug management: results of a pilot, randomized, controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Deer TR, Mekhail N, Provenzano D, et al. Neuromodulation Appropriateness Consensus Committee. The appropriate use of neurostimulation of the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system for the treatment of chronic pain and ischemic diseases: the Neuromodulation Appropriateness Consensus Committee. Neuromodulation. 2014 Aug;17(6):515–50. doi: 10.1111/ner.12208. discussion 550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Almeida C, DeMaman A, Kusuda R, et al. Exercise therapy normalizes BDNF upregulation and glial hyperactivity in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2015;156(3):504–13. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460339.23976.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Allen NE, Moloney N, van Vliet V, Canning CG. The Rationale for Exercise in the Management of Pain in Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2015 Feb 3; doi: 10.3233/JPD-140508. (In Press, Ahead of Print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Raphael W, Sordillo LM. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation: the role of phospholipid biosynthesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(10):21167–88. doi: 10.3390/ijms141021167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hadjivassiliou M, Grünewald RA, Kandler RH, et al. Neuropathy associated with gluten sensitivity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(11):1262–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.093534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]