Abstract

Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) have served as an important model for studies of reproductive diseases and aging-related disorders in humans. However, limited information is available about spontaneously occurring reproductive tract lesions in aging chimpanzees. In this article, the authors present histopathologic descriptions of lesions identified in the reproductive tract, including the mammary gland, of 33 female and 34 male aged chimpanzees from 3 captive populations. The most common findings in female chimpanzees were ovarian atrophy, uterine leiomyoma, adenomyosis, and endometrial atrophy. The most common findings in male chimpanzees were seminiferous tubule degeneration and lymphocytic infiltrates in the prostate gland. Other less common lesions included an ovarian granulosa cell tumor, cystic endometrial hyperplasia, an endometrial polyp, uterine artery hypertrophy and mineralization, atrophic vaginitis, mammary gland inflammation, prostatic epithelial hyperplasia, dilated seminal vesicles, a sperm granuloma, and lymphocytic infiltrates in the epididymis. The findings in this study closely mimic changes described in the reproductive tract of aged humans, with the exception of a lack of malignant changes observed in the mammary gland and prostate gland.

Keywords: biological aging, chimpanzee, genital organs, female, genital organs, male, mammary glands, pathology, leiomyoma, uterine

In the 21st century, there has been a global demographic shift such that the number of individuals >60 years old is increasing rapidly in both developed and nondeveloped nations.19,87 As the number of aged adults in the United States continues to expand, it becomes increasingly important to understand the changes that characterize reproductive aging and their effect on this population.1,22,30,95 Not only do reproductive aging and senescence mark a decline or cessation in fertility, but the associated hormonal changes also often adversely affect the quality of life, especially in postmenopausal females. With changing socioeconomic priorities and increased availability of advanced medical fertility technology, the average age at first childbearing is gradually increasing, resulting in a shorter reproductively fertile period following first conception.62 Since the 19th century, the human life span has doubled, and the life expectancy in developed countries has progressively increased to >70 years.30 Men and women are living longer; however, the pace of reproductive aging far exceeds the pace of somatic aging, resulting in a long period of postreproductive senescence, especially for females.1,50,60 Some researchers suggest that the unusually long postfertile life in human females is an evolutionary advantage, as it enables multigenerational support in raising young.39,40,60 However, further research is warranted to better understand the biology of reproductive aging to improve the quality of life and possibly delay the process of reproductive aging.39,40,49,55 Given the ethical and practical restrictions of research on reproductive aging using humans, several animal models have been proposed, ranging from rodents to nonhuman primates, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.61,92

The choice of an appropriate model depends on several factors, including phylogenetic closeness to humans, longevity, rate of aging, reproductive physiology, and hormonal and biochemical profiles. Based on these factors, nonhuman primates (specifically macaques, baboons, and chimpanzees) stand out as good candidates.61 Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are phylogenetically the closest living human relative and have similar hormonal, biochemical, and behavioral patterns as human beings.* The life span of chimpanzees in the wild ranges from 15 to 19 years.43,67 In captivity, their life span is significantly longer, and it is not uncommon for chimpanzees to live 40 to 50 years and show a similar aging pattern to that of humans.13,43 However, studies in chimpanzees are subject to many of the same potential limitations as studies in humans, such as variable history of contraceptive use and incomplete or incorrect histories of infectious diseases of the reproductive tract. In addition, research in chimpanzees will be very limited in the future due to the recent recommendations published by the National Institutes of Health.68

Much of the research on nonhuman primate reproductive aging is focused on menopause, and there is considerable debate whether chimpanzees are a suitable model for studying menopause.† Some researchers have proposed that menopause in midlife with a long postfertile life span is unique to women. Others contend that reproductive decline is a universal phenomenon in all primates, and chimpanzees, like humans, do exhibit reproductive decline. Studies have shown that in female chimpanzees, there are signs of reproductive aging after 30 to 35 years characterized by increased menstrual cycle length, decreased frequency of estrus, reduced rate of conception, depletion of ovarian follicles, and fibrosis of the ovaries.‡ However, unlike humans, there is no abrupt decline or cessation of fertility, and instead of menopause, perimenopause or premenopause seems to be a more appropriate term to describe this phenomenon in chimpanzees. This is a simplistic explanation, and the debate continues, although many are of the opinion that female chimpanzees remain fertile until the fifth or sixth decade of their lives, which in most cases covers their entire life span.§ In contrast to female chimpanzees, reproductive aging in male chimpanzees remains largely undefined.30 Except for the occurrence of benign prostatic hyperplasia in captive aged male chimpanzees,85 there are no reports of an age-associated decline in fertility of male chimpanzees.30

There are a limited number of publications describing the spontaneous pathology of the reproductive tract in chimpanzees. Most are in the form of case reports or case series, including reports of adenomyosis,10 leiomyoma,14,37,82,90 endometrial stromal tumors,86 and Sertoli cell tumors.38 Here we describe spontaneous lesions and normal aging-associated changes seen in the reproductive tract of 67 aged (>35 years) captive chimpanzees housed at 3 primate centers in the United States. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive retrospective examination of spontaneous reproductive lesions in captive chimpanzees.

Materials and Methods

All chimpanzees >35 years old that had archived histologic slides of reproductive tissue, that were considered of reasonable quality, were included in this study. The majority of tissues were collected at necropsy; however, some were surgical specimens. Thirty-five years was chosen as the cutoff age based on (1) published data indicating that female chimpanzees show evidence of reproductive aging around 30 to 35 years and (2) the attending veterinarian’s clinical impression of what constituted an aged animal.36,37 Tissues from 3 research centers accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) in the southwest United States were included: Michale A. Keeling Center for Comparative Medicine and Research, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Bastrop, Texas; Texas Biomedical Research Institute, San Antonio, Texas; and Alamogordo Primate Facility, Alamogordo, New Mexico. Thirty-three female chimpanzees >35 years old were identified from the 3 facilities. They ranged in age from 35 to 56 years, and the median age was 43 years. For females in which parity data were available (n = 18), animals ranged from nulliparous to 10 offspring, with a median of 3 offspring. Information on contraceptive method use was also available in 18 of these animals. Methods included intrauterine device, oral contraceptive (0.3 mg, norgestrel; 0.03 mg, estradiol), Implanon (etonogestrel implant), and Norplant (levonorgestrel implant). Contraceptives were administered per manufacturer guidelines. Animals not receiving contraceptives were housed only with vasectomized males or had previously undergone hysterectomy. In the 33 females included in the study, histologic slides of the following tissues were examined: ovaries from 27 animals, uterus from 32, vagina from 10, and mammary gland from 16 (Table 1). Thirty-four male chimpanzees >35 years old were identified from the 3 facilities. The animals ranged from 35 to 53 years of age with a median age of 40 years. Clinical data were available for 9 of the males, and of these, 1 had undergone a vasectomy procedure. In the 34 male animals included in the study, slides of the following tissues were examined: testes from 32 animals, prostate from 16, epididymides from 14, and seminal vesicles from 23 (Table 2). Clinical data were reviewed for the 19 females and 9 males from the MD Anderson Cancer Center. Clinical data from the other 2 institutions were not available for review.

Table 1.

Lesions in the Reproductive Tract of Aged Female Chimpanzees.

| Organ | Affected Animals, n (%) | Age Range (Average), y

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Affected | Unaffected | ||

| Ovary | |||

| Atrophya | 27 of 27 (100) | 35–53 (42.9) | — |

| Neoplasia | 1 of 27 (3.7) | 41 | 35–53 (42.9) |

| Uterus | |||

| Leiomyoma | 20 of 32 (62.5) | 35–56 (44.4) | 36–51 (41.2) |

| Adenomyosis | 8 of 32 (25) | 39–46 (43.4) | 35–56 (43) |

| Endometrial atrophy | 10 of 16b (62.5) | 39–53 (45.1) | 39–53 (44.2) |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 2 of 16b (12.5) | 40–50 (45) | 39–53 (44.2) |

| Vascular changesc | 4 of 32 (12.5) | 36–53 (43) | 35–56 (43.1) |

| Vagina: atrophy and inflammation | 2 of 10 (20) | 44–46 (45) | 41–53 (46) |

| Mammary gland | |||

| Inflammation | 1 of 16 (6.3) | 44 | 35–53 (43.9) |

| Arterial hyalinization | 2 of 16 (l2.5) | 43–44 (43.5) | 35–53 (43.9) |

Ovarian atrophy included the following histologic findings: decreased or absent primordial follicles with clustering of those remaining, few developing follicles, cortical and medullary fibrosis, tortuous vessels with wall thickening and hyalinization.

Sections of uterus were evaluated in 32 animals; however, only 16 animals had adequate endometrium for evaluation.

Vascular changes in the uterus included the following histologic findings: intimal proliferation and thickening, medial hypertrophy and mineralization, or fibrinoid degeneration of the tunica media.

Table 2.

Lesions in the Reproductive Tract of Aged Male Chimpanzees.

| Organ | Affected Animals, n (%) | Age Range (Average), y

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Affected | Unaffected | ||

| Testes | |||

| Degeneration | 20 of 32 (62.5) | 35–53 (42.4) | 35–53 (40.1) |

| Inflammation | 4 of 32 (12.5) | 40–53 (45.3) | 35–53 (41.0) |

| Hemosiderophages | 1 of 32 (3.1) | 36 | 35–53 (41.2) |

| Prostate gland | |||

| Periglandular lymphocytes | 11 of 16 (68.8) | 35–47 (40.9) | 35–49 (39.8) |

| Degeneration of glands | 7 of 16 (43.8) | 36–49 (41.6) | 35–49 (41.1) |

| Periglandular fibrosis | 3 of 16 (18.8) | 37–47 (40.7) | 35–49 (40.5) |

| Hyperplastic glandular epithelium | 3 of 16 (18.8) | 37 (37) | 35–49 (41.4) |

| Epididymis | |||

| Inflammation | 3 of 14 (21.4) | 36–47 (4I.3) | 35–53 (43.0) |

| Hemosiderophages | 2 of 14 (l4.2) | 41–47 (44) | 35–53 (42.4) |

| Sperm granuloma | 1 of 14 (7.1) | 41 | 35–53 (42.8) |

| Seminal vesicles glandular dilation | 1 of 23 (4.3) | 39 | 35–53 (41.5) |

Results

Ovary

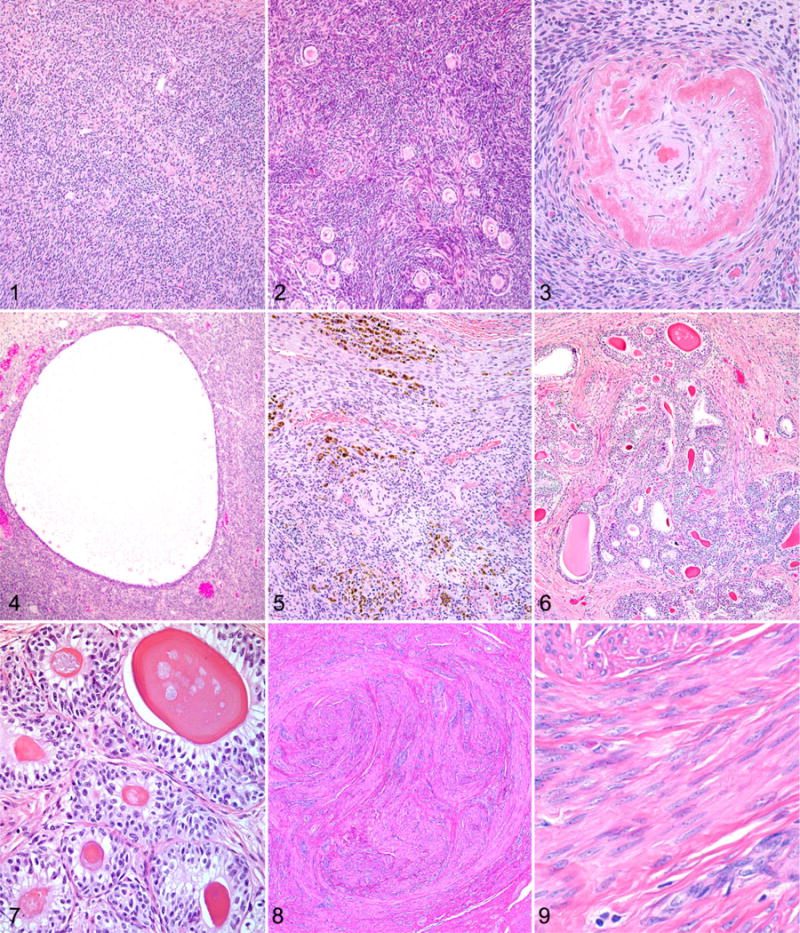

The ovaries were examined from 27 chimpanzees with an average age of 43 years. All animals exhibited histologic changes of ovarian aging, consistent with those previously reported in both humans and nonhuman primates.‖ The most commonly noted changes included decreased or absent primordial follicles (Fig. 1) with clustering of those remaining (Fig. 2), few developing follicles, cortical and medullary fibrosis, and tortuous vessels with vascular wall thickening and hyalinization (Fig. 3). Less frequently recorded findings in this group included persistent corpora albicantia (the regressed form of corpora lutea), follicular cysts (Fig. 4), aggregates of adipocytes within the stroma, and remnants of corpora lutea. Several of the most severely affected ovaries were from chimpanzees aged 40, 41, and 43 years, while the mildest changes were noted in animals aged 35, 41, 42, and 44 years. Many of the animals also had multifocal deposits of hemosiderin and/or hemosiderophages (Fig. 5) within the cortical and medullary stroma, and to our knowledge, this finding has not previously been reported in aged chimpanzee ovaries. The presence of hemosiderin was confirmed by Prussian blue staining.

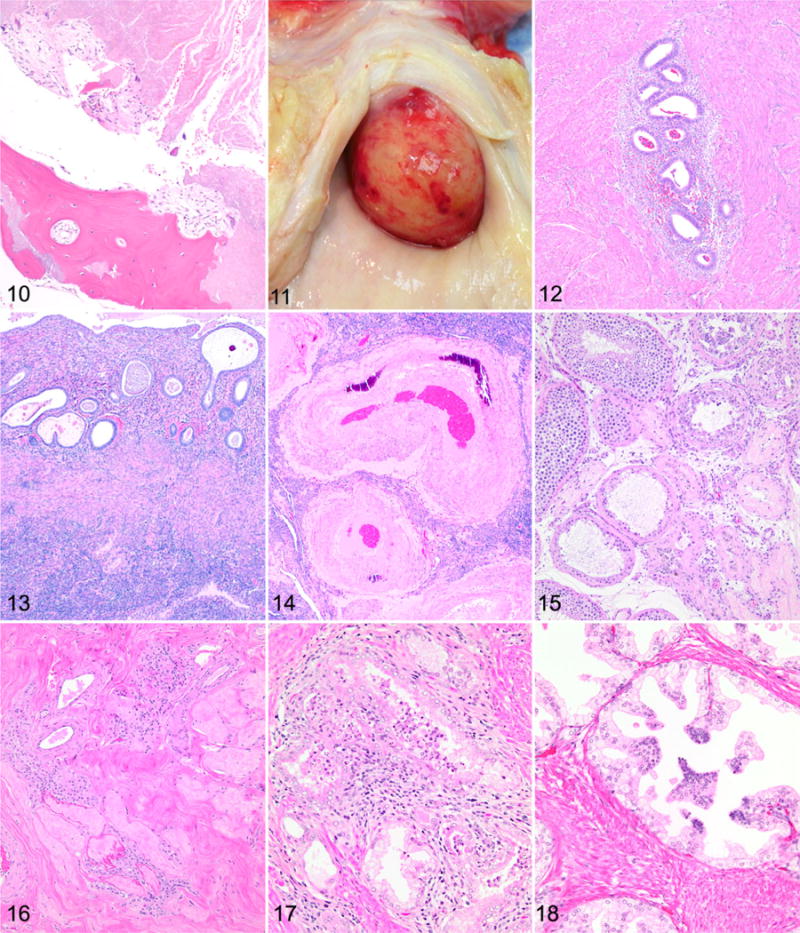

Figures 1–3. Ovarian atrophy, chimpanzee. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Figure 1. 45-year-old. There is an absence of primordial follicles within the cortex. Figure 2. 42-year-old. Remaining primordial follicles are situated in clusters within the ovarian cortex. Figure 3. 44-year-old. Frequent vessels within the ovary exhibit wall thickening and hyalinization. Figure 4. Follicular cyst, ovary, chimpanzee, 43 years old. A cyst is present within the ovarian cortex. HE. Figure 5. Ovary, chimpanzee, 47 years old. There are multifocal clusters of hemosiderophages and free hemosiderin within the ovarian cortex. HE. Figures 6 and 7. Granulosa cell tumor, ovary, chimpanzee, 41 years old. HE. Figure 6. Neoplastic cells are arranged in nests and often form rosette-like structures that surround eosinophilic hyaline material (Call-Exner bodies). Figure 7. Polygonal to columnar cells have variably distinct cell borders and a moderate amount of vacuolated pale eosinophilic cytoplasm. Figures 8 and 9. Leiomyoma, uterus, chimpanzee, 47 years old. HE. Figure 8. The neoplasm in the endometrium is composed of interlacing bundles of smooth muscle cells. Figure 9. Neoplastic cells are characterized by an elongate nucleus with coarsely stippled chromatin and an elongated, spindyloid, eosinophilic cell body. Figures 10 and 11. Leiomyoma, uterus, chimpanzee, 41 years old. Figure 10. Osseous metaplasia is present in this leiomyoma, surrounded by necrotic tissue at the center of the mass. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Figure 11. A large cervical leiomyoma protrudes into the vagina and led to heavy bleeding. Figure 12. Adenomyosis, uterus, chimpanzee, 43 years old. Clusters of endometrial glands and surrounding stroma within the myometrium. HE. Figure 13. Endometrial atrophy, uterus, chimpanzee, 44 years old. Atrophic endometrium with fluid-filled, dilated, and irregularly oriented glands. HE. Figure 14. Arterial hypertrophy and mineralization, uterus, chimpanzee, 41 years old. Uterine artery with thickened and mineralized arterial wall. HE. Figures 15 and 16. Testicular atrophy, chimpanzee, 47 years old. HE. Figure 15. There is variable loss of the seminiferous tubular epithelium and spermatids with some sclerotic tubules. Figure 16. There is diffuse atrophy of the seminiferous tubular epithelium with no sperm present, sclerosis of the tubules, and fibrosis of the interstitium but with preservation of some of the interstitial cells. HE. Figure 17. Lymphocytic infiltrates, prostate gland, chimpanzee, 37 years old. There is periglandular lymphocytic infiltration, neutrophils within glands, and periglandular fibrosis. HE. Figure 18. Prostatic glandular epithelial hyperplasia, chimpanzee, 37 years old. There is multifocal hyperplasia of basaloid cells. HE.

One ovary from a 41-year-old chimpanzee contained a small mass that was well circumscribed and composed of lobules of neoplastic cells separated by fibrous connective tissue. Within the lobules, neoplastic cells were arranged in nests and often formed rosette-like structures that surrounded an eosinophilic hyaline material (Call-Exner bodies; Fig. 6). Neoplastic cells were polygonal to columnar, with variably distinct cell borders and a moderate amount of vacuolated pale eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 7). Nuclei were round to oval with finely stippled chromatin and generally 1 distinct basophilic nucleolus. No mitoses were noted. The histologic features of this mass were consistent with a granulosa cell tumor.

Uterus

Uterine tissue was evaluated in 32 chimpanzees with an average age of 43 years. The amount of endometrium and myometrium varied from specimen to specimen, and the orientation of the tissue section was not always apparent. The majority of the uterine tissues were collected at necropsy; however, 7 were surgical specimens from hysterectomy procedures. The most commonly observed lesions were leiomyomas, adenomyosis, and endometrial atrophy.

Leiomyomas were present in 20 animals and were variably sized, often multiple, and they also occurred in the cervix. In animals in which the contraceptive history was known (n = 18), there did not appear to be any relationship between contraceptive use and the prevalence of leiomyomas, nor did there appear to be any relationship with parity. All 4 methods of contraception (intrauterine device, oral, Implanon, Norplant) were represented in the leiomyoma group and in the unaffected group. Animals with leiomyomas had given birth to 0 to 5 infants, with an average of 2.2 infants per female. Animals without leiomyomas had given birth to 1 to 4 infants (average, 2.8), excluding 1 outlier that had given birth to 10 infants. Microscopically, leiomyomas were composed of interlacing streams and bundles of smooth muscle cells that were poorly to moderately demarcated from the surrounding myometrium and formed expansile masses (Fig. 8) that sometimes protruded from the serosal or luminal surface. The cells were characterized by an elongate nucleus with coarsely stippled chromatin and an elongated, spindyloid, eosinophilic cell body (Fig. 9). In some leiomyomas, there was an increased nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio. There was minimal to mild anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, and mitoses were uncommon. Larger leiomyomas sometimes had necrosis, particularly toward the center of the mass. One leiomyoma contained areas of mineralization and a focus of osseous metaplasia (Fig. 10). For animals in which the clinical history was well documented, there were rarely any clinical signs attributable to the leiomyomas. However, in 1 animal (45 years old), a large cervical leiomyoma (3–4 cm in diameter) led to heavy vaginal bleeding, and the animal was euthanized (Fig. 11).

Adenomyosis was present in 8 animals and was characterized by ectopic endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrial wall at least one 400 × field from the base of the uterine epithelium (Fig. 12). The glandular epithelium lacked any evidence of atypia or mitotic figures. Foci of adenomyosis were usually small and typically composed of 5 to 10 glands and a small area of stroma <5 mm in diameter. However, some foci contained dilated cystic glands and were larger. In some foci of adenomyosis, the surrounding myometrial cells were mildly hyperplastic. There did not appear to be a relationship between contraceptive history or parity and the occurrence of adenomyosis. Of the 8 animals with adenomyosis, 2 had been on oral contraceptives, 1 on Implanon, 1 on Norplant, 2 with no contraceptives and 2 with an unknown history. Of the 6 animals with adenomyosis that had clinical history available, 4 had given birth to 2 infants, and 2 had given birth to 3 infants.

Sixteen specimens contained adequate endometrial tissue for evaluation. Ten of these animals demonstrated variable evidence of endometrial atrophy. Atrophic endometrium was thinner (approximately 700 μm), and the surface epithelium was flattened and inactive. The endometrium contained fewer glands, with some glands being lined by cuboidal epithelium and filled with proteinaceous secretory material (Fig. 13). In the less severely atrophic specimens, some glands resembled normal proliferative phase glands but lacked mitotic figures. The demarcation between the stratum basalis and the stratum functionalis was often indistinct. The stroma of atrophic endometrium was most commonly composed of spindyloid cells within a fibrous stroma; however, in 1 animal the stroma had a decidual morphology.

Vascular changes were present in 4 animals and affected the large arcuate and radial arteries. Changes included intimal proliferation and thickening, medial hypertrophy and mineralization, or fibrinoid degeneration of the tunica media (Fig. 14). In one 42-year-old female, the mineralization had been diagnosed antemortem with ultrasound during a routine annual physical examination. This animal also had a history of chronic hypertension. A 41-year-old female with vascular mineralization had given birth to 10 infants, the most of any of the animals with a birth history available. No history was available for the remaining 2 females with vascular changes in the uterus.

A 40-year-old female and a 50-year-old female had endometrial hyperplasia with cystic glandular dilation. The endometrium in these animals measured up to 7.5 mm thick with numerous dilated glands containing secretory material. One 43-year-old female had an endometrial polyp. The polyp was composed of endometrial glands and stroma with numerous cystic secretion-filled glands. No atypia was present in the polyp. One 44-year-old female had a focal area of mineralization in the myometrium that was surrounded by a small focus of macrophages and scattered lymphocytes. Unlike the other animals with mineralization of the large arteries, the mineralization in this animal was not associated with the vasculature.

Vagina

Vaginal tissue was examined from 10 chimpanzees with an average age of 46 years. In 8 of the 10 chimpanzees, the vaginal wall was considered normal. The mucosal epithelium in these 8 animals was 125 to 250 μm thick and composed of non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium arranged in layers of 15 to 20 cells. However, in 2 of the submissions aged 44 and 46 years, the mucosal epithelium was thinner (<125 μm) with fewer cell layers (~ 10 cells thick). Also, infiltrates of lymphocytic and histiocytic cells were more prominent in the submucosa and were admixed with low numbers of neutrophils within the mucosa. These changes suggest an ongoing inflammatory reaction and atrophy of the mucosa.

Mammary Gland

Mammary tissues were examined from 16 female chimpanzees with an average age of 44 years. For inclusion, the samples needed to contain large and small ducts (ductules, terminal ducts) and lobular acinar units embedded in stroma (fibrous and/or adipose tissues). None of the animals were nursing an infant at the time of tissue collection. All 8 chimpanzees for which the reproductive history was available had previously given birth, with the number of births ranging from 1 to 10. In addition, 6 of these 8 received oral or implanted contraceptives, and 2 had undergone ovariohysterectomies.

In 8 of the 16 chimpanzees, the lobular acinar units were small (<50 × 100 μm) and scattered within a loose stroma of fibrous and/or adipose tissue. The units had small lumens and were lined by cuboidal cells in single or double layers. Little intralobular stroma was present, and low numbers of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and occasional mast cells were observed in the surrounding interlobular stroma. Terminal ductules and ducts were small, but large ducts were present extending into the dermal collagen. The units were considered to be reduced in size and number and inactive. The median age of the animals with inactive glands was 42.3 years. Three animals in this group had a history of having between 2 and 5 offspring; data were not available for the remaining 5 animals.

In 4 chimpanzees, the lobular acinar units were prominent (~600 × 1250 μm), with variably sized lumens often filled with light eosinophilic fluid, and were lined by a single layer of cuboidal cells. However, some acini were ectatic and lined by large epithelial cells that protruded into the lumen. The intralobular fibrous stroma was conspicuous and divided individual acinar units with a lobule. This stroma contained low numbers of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and/or mast cells. The extralobular stroma was variably loose or dense and composed of fibrous or adipose tissues. Ducts that extended to the dermis and surface were often large and ectatic and frequently contained prominent amounts of eosinophilic fluid. Occasional small lymphoid nodules were observed around larger lobules and ducts. The mammary gland morphology in these chimpanzees was consistent with glandular activity and production of milk (lactation). The median age of the animals with active glands was 43.8 years. Five chimpanzees in this group had a history of having between 1 and 10 offspring.

The remaining 4 chimpanzees had mammary gland changes that included both inactive and active lobular acinar units and ducts. One animal in this group had several small ducts in the acinar unit area that had swollen, vacuolated epithelial lining cells, lumens containing low numbers of neutrophils, and mild periductal infiltrates of lymphocytes and some plasma cells. This was the only animal with an apparent active inflammatory process. Also, 2 chimpanzees in this group had several arteries in the area of the lobular acinar units with hyalinization of the wall. Although a clinical history was not available, the arterial change was suggestive of hypertension.52

Tests

Testes from 32 animals were examined, of which 20 were identified as having degenerative changes present. These changes consisted of a seeming continuum, from loss of few spermatids and seminiferous tubular epithelium with hypospermatogenesis, to complete loss of spermatids and seminiferous tubular epithelial cells in the tubules, thickening of the tubular basement membranes, and fibrosis (sclerosis). Occasionally, seminiferous tubules contained multinucleated giant cells. Sertoli cell morphology appeared normal in the remaining tubules. In most cases, these changes were multifocal (Fig. 15), but in 1 case there was complete loss of spermatids and epithelium, and diffuse thickening of the basement membranes but with preservation of interstitial cells (Fig. 16). Mild lymphocytic infiltrates were detected in 4 testes, and in 1 there were scattered hemosiderophages.

Prostate Gland

Prostate was evaluated in 16 animals, and 12 had abnormalities. The most common lesion in the prostate was periglandular lymphocytic infiltrates, present in 11 animals. Seven had lymphocytic infiltrates with degeneration of glandular epithelium and rare neutrophils in glands, and 3 animals had periglandular fibrosis in association with lymphocytic infiltrates (Fig. 17). The lymphocytic infiltrates were usually minimal to mild, with only 2 cases considered to be moderate. Another lesion observed in the prostate was hyperplastic glandular epithelium, which was found in 3 animals. Hyperplastic epithelium consisted of multifocal areas of epithelial cells with greater numbers of basaloid cells, often forming papillary protections into the glandular lumens (Fig. 18). Corpora amylacea, sometimes mineralized, were present in all prostates and were considered normal findings.

Epididymis and Seminal Vesicle

Of 14 epididymides examined, 3 had lesions. All 3 had mild lymphocytic infiltrates; 2 also had scattered hemosiderophages. In addition, 1 of the animals with scattered hemosiderophages in the epididymis had a sperm granuloma. The identification of hemosiderin was based on the morphology of the pigment, and other pigments, such as lipofuscin, were not definitively ruled out. Of the 23 seminal vesicles examined, 1 had a lesion consisting of dilation of the gland with attenuation of the epithelium.

Discussion

In women, reproductive senescence is characterized by cessation of menstrual cycling, ovulation, and ovarian steroid hormone production.24,32,47,84 Thus, the ovary is an important regulator of mammalian reproductive senescence.91,93 Aging of the ovary involves transition from a follicular-rich organ that is actively and cyclically secreting hormones (estrogen and progesterone) to an organ that is atrophic, follicle depleted, and producing low levels of progesterone.57,58,64 Apoptosis causes most of the atrophic changes and exhibits increased activity during the perimenopausal period and after menopause.58 Structural changes in the aged human ovary have been noted to occur after menopause, and the health and quality of human oocytes are cited to progressively decline with age.18,31,34,51,58,70

Ovaries from all 27 chimpanzees examined here exhibited histologic changes of aging, consistent with those previously reported in both humans and nonhuman primates. These included decreased or absent primordial and developing follicles, cortical and medullary fibrosis, vascular changes, persistent corpora albicantia and remnant corpora lutea, follicular cysts, stromal adipocyte aggregates, and deposits of hemosiderin and/or hemosiderophages. The severity of the ovarian aging changes ranged from mild to marked, with the majority of animals having at least moderately prominent findings. There was no difference in the severity of ovarian lesions among the 3 facilities. There was no apparent correlation between use or type of birth control and the severity of aging changes noted in the ovaries examined. Interestingly, those animals of the most advanced age did not always have the most severe lesions. For example, several of the most severely affected ovaries were from chimpanzees with similar ages as those with the mildest changes.

Menopause is presumed to occur when the total number of available follicles is depleted to a level at which estrogen secretion drops and ovulation terminates.5,64,69,94 In women, this occurs when the follicular store is depleted to approximately <1000.25,35 Loss of or markedly decreased numbers of primordial and developing follicles were a common, often prominent, finding in this cohort of chimpanzees. Although quantification of follicle number was not possible in these animals, due to sample limitations, it is interesting to speculate whether this degree of follicular loss would correlate with menopause in these chimpanzees.

The lesions observed in the uterus of aged chimpanzees in this study closely resembled what are reported in humans.¶ There was a high incidence of leiomyomas (fibroids), which in many animals were numerous. Up to 80% of women aged 50 years have leiomyomas, and fibroids are the leading indication for hysterectomy in women.8,73 Although benign, leiomyomas can cause heavy vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, and infertility.16 In the female chimpanzees in which clinical history was available, only 1 had documented clinical signs associated with a leiomyoma. This animal had a large cervical fibroid that caused severe vaginal bleeding. In contrast to a previous study,90 we were unable to detect any difference in the incidence of leiomyoma among animals on different contraceptive methods. However, we had limited data available, so it would be unwise to draw definitive conclusions about contraceptive use from our data.

Adenomyosis, another common finding in women, was present in several of our chimpanzees. Although only reproductive tissues were examined in this study, it was interesting to note that endometriosis was not listed in the history or necropsy report of any of the 19 aged females from the MD Anderson Cancer Center. It appears that although adenomyosis is common, endometriosis is an a rare diagnosis in chimpanzees, in contrast to humans, in which an estimated 10% of the overall population is affected by endometriosis.74 The endometrial atrophy seen in these chimpanzees could be attributable to an aging change, but it could also be the result of long-term contraceptive use.4,20,29 Cystic endometrial hyperplasia, seen in 2 females, can also be associated with long-term contraceptive use.21 Both of the animals with cystic endometrial hyperplasia had been on contraceptives: 1 on oral contraceptive and 1 on Implanon. Because the contraceptive history was unknown in many of the animals and because of the various methods employed, it was not possible to draw any conclusions about contraceptive use and the incidence or severity of the endometrial changes.

The vascular changes seen in the uterus of 4 animals were likely due to vascular remodeling that occurs during pregnancy, although previous pregnancy could be confirmed in only 2 of the animals (3 and 10 offspring). Interestingly, the animal that had the most previous pregnancies (10 offspring) was one of the animals with vascular changes. Uterine vessels undergo vascular remodeling during pregnancy to allow for increased uteroplacental blood flow, and these changes include hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the vascular smooth muscle.72 Although blood flow will return to normal postpartum, the vascular changes are not completely reversible.72,80 Alternatively, for some animals, the changes might be attributable to systemic disease, particularly in the case of the animal with a documented history of hypertension.71

The vaginal tissues of aged chimpanzees showed features as described for the normal vagina of humans.53,66 There were no differences in vaginal features across the ages represented in this survey. Two animals had mild inflammation in the mucosal layer and mild atrophy. The mucosal atrophy and vaginitis were similar to that described in aged humans.27 Decreased vaginal secretions, increased pH, and thinned mucosa all contribute to the atrophic vaginitis described in aged human females.17,26,59

Evaluation of the mammary gland showed that the glands from half of the animals were in an inactive state. Of the remaining animals, 4 had active lactating glands, while 4 had a combination of inactive and active glands. The mammary changes occurred across all ages represented in this survey. The chimpanzee mammary gland features were similar to those described in human breast tissue53,66,77,78; however, benign epithelial lesions (nonproliferative, proliferative, and atypical hyperplastic) and carcinoma of the breast, which are common in humans, were not observed in any of the animals.53 Approximately 1 in 8 women in the United States will develop breast cancer in her lifetime,44 so it is interesting to note the rarity of breast cancer in chimpanzees, despite their phylogenetic closeness to humans.

Notwithstanding a previous study suggesting that benign prostatic hyperplasia was common in adult chimpanzees, we did not detect nodules consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia in the chimpanzees in this study.85 Glandular cell hyperplasia was occasionally detected; however, this change was found in a limited number of chimpanzees (3 of 16 examined), and neoplastic changes or atypical hyperplasia, common in humans, was not seen.45 Another lesion that is common in humans is lymphocytic infiltrates, which were detected in 11 chimpanzee prostates.45,79

Most testicular and epididymal lesions are likely to be related to aging or secondary to vasectomy, commonly used for sterilization in the chimpanzees. Aging changes in the testes of humans include variable atrophy of seminiferous tubules, tubular basement membrane thickening, and sometimes sclerosis of the tubules, similar to what was seen in these chimpanzees.46 All of these changes have also been reported in macaques and humans following vasectomy.63,76,81 This has implications for reversal of vasectomies, as loss of the seminiferous tubules will result in reduced viable sperm production, although the mechanism of seminiferous tubular atrophy and subsequent sperm reduction is not known.63 Complete records for all chimpanzees were not available, so the actual number of vasectomized chimpanzees was not determined, although at least 8 were not vasectomized. The presence of mild lymphocytic infiltrates in 4 testes and in 3 epididymides, as well as a sperm granuloma in 1 epididymis, and hemosiderin in 2 testes and 2 epididymides are of undetermined etiology; however, these seem unlikely to be aging changes. In 1 animal, complete loss of the testicular epithelial component but preservation of the interstitial cells suggests a transient ischemic event, possibly associated with vasectomy, or some other event that targeted the seminiferous tubules.

The changes observed in the aged chimpanzee reproductive tract were similar to what are reported in humans; however, there were some key differences. The most common findings were ovarian atrophy, uterine leiomyoma, adenomyosis, endometrial atrophy, seminiferous tubule degeneration in the testes, and lymphocytic infiltrates in the prostate. Age-associated findings in humans that were not seen in chimpanzees included mammary epithelial hyperplasia and carcinoma, endometriosis, and prostatic atypical epithelial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Although this is the most comprehensive study examining reproductive system lesions in aging chimpanzees, the sample size was still extremely small as compared with epidemiologic studies in humans. In addition, this population was limited to captive chimpanzees at research centers in the southwest United States, and we must be cautious about extrapolating the data to make conclusions about all populations of chimpanzees. Nonetheless, the overall similarity to human reproductive aging but reduced incidence of malignant and premalignant lesions underscores the importance of chimpanzees in understanding reproductive system aging.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Alberts SC, Altmann J, Brockman DK, et al. Reproductive aging patterns in primates reveal that humans are distinct. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(33):13440–13445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311857110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altmann J, Gesquiere L, Galbany J, et al. Life history context of reproductive aging in a wild primate model. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1204:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appt SE, Ethun KF. Reproductive aging and risk for chronic disease: Insights from studies of nonhuman primates. Maturitas. 2010;67(1):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer DF, McIntyre-Seltman K, Wilborn WW, Jr, et al. Endometrial morphology in asymptomatic postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(2):317–320. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atkins HM, Willson CJ, Silverstein M, et al. Characterization of ovarian aging and reproductive senescence in vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) Comp Med. 2014;64(1):55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atsalis S, Margulis S. Primate reproductive aging: from lemurs to humans. Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2008;36:186–194. doi: 10.1159/000137710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atsalis S, Videan E. Reproductive aging in captive and wild common chimpanzees: factors influencing the rate of follicular depletion. Am J Primatol. 2009;71(4):271–282. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):100–107. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balan R, Crauciuc E, Gheorghita V, et al. Morphologic aspects of the senescence processes in female genital system. Genetica si Biologie Moleculara. 2008;9:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrier BF, Allison J, Hubbard GB, et al. Spontaneous adenomyosis in the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes): a first report and review of the primate literature: case report. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1714–1717. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellino FL, Wise PM. Nonhuman primate models of menopause workshop. Biol Reprod. 2003;68(1):10–18. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benagiano G, Brosens I, Habiba M. Structural and molecular features of the endomyometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(3):386–402. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bloomsmith MA, Brent LY, Schapiro SJ. Guidelines for developing and managing an environmental enrichment program for nonhuman primates. Lab Anim Sci. 1991;41(4):372–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown SL, Anderson DC, Dick EJ, Jr, et al. Neoplasia in the chimpanzee (Pan spp) J Med Primatol. 2009;38(2):137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2008.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buse E, Zoller M, Van Esch E. The macaque ovary, with special reference to the cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis) Toxicol Pathol. 2008;36(7):24S–66S. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buttram VC, Jr, Reiter RC. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril. 1981;36(4):433–445. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)45789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cauci S, Driussi S, De Santo D, et al. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis and vaginal flora changes in peri- and postmenopausal women. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(6):2147–2152. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2147-2152.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clement PB. Histology of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11(4):277–303. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conn PM. Handbook of Models for Human Aging. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deligdisch L. Hormonal pathology of the endometrium. Mod Pathol. 2000;13(3):285–294. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinh A, Sriprasert I, Williams AR, et al. A review of the endometrial histologic effects of progestins and progesterone receptor modulators in reproductive age women. Contraception. 2015;91(5):360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellison PT, Ottinger MA. A comparative perspective on reproductive aging, reproductive cessation, post-reproductive life, and social behavior. In: Weinstein M, Lane MA, editors. Sociality, Hierarchy, Health: Comparative Biodemography. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. pp. 315–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emery Thompson M, Jones JH, Pusey AE, et al. Aging and fertility patterns in wild chimpanzees provide insights into the evolution of menopause. Curr Biol. 2007;17(24):2150–2156. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faddy MJ, Gosden RG. Ovary and ovulation: a model conforming the decline in follicle numbers to the age of menopause in women. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(7):1484–1486. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faddy MJ, Gosden RG, Gougeon A, et al. Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause. Hum Reprod. 1992;7(10):1342–1346. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farage MA, Maibach HI. Morphology and physiological changes of genital skin and mucosa. Curr Probi Dermatol. 2011;40:9–19. doi: 10.1159/000321042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farage MA, Miller KW, Maibach HI. Textbook of Aging Skin. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fauser BC. Follicle pool depletion: factors involved and implications. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(4):629–630. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01530-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferenczy A, Bergeron C. Histology of the human endometrium: from birth to senescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;622:6–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finch CE. Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: evolution of the human lifespan and diseases of aging: roles of infection, inflammation, and nutrition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(suppl 1):1718–1724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909606106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giacobbe M, Pinto-Neto AM, Costa-Paiva LH, et al. Ovarian volume, age, and menopausal status. Menopause. 2004;11(2):180–185. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000082296.62794.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsberg J. What determines the age at the menopause? BMJ. 1991;302(6788):1288–1289. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golan A, Cohen-Sahar B, Keidar R, et al. Endometrial polyps: symptomatology, menopausal status and malignancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010;70(2):107–112. doi: 10.1159/000298767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez OV, Martinez NL, Rodriguez G, et al. Pattern of vascular aging of the postmenopausal ovary. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 1992;60:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gosden RG, Faddy MJ. Biological bases of premature ovarian failure. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1998;10(1):73–78. doi: 10.1071/r98043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gould KG, Flint M, Graham CE. Chimpanzee reproductive senescence: a possible model for evolution of the menopause. Maturitas. 1981;3(2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(81)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham CE. Reproductive function in aged female chimpanzees. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1979;50(3):291–300. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330500302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham CE, McClure HM. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor in a chimpanzee. Lab Anim Sci. 1976;26(6, pt 1):948–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawkes K. Colloquium paper: how grandmother effects plus individual variation in frailty shape fertility and mortality: guidance from human-chimpanzee comparisons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(suppl 2):8977–8984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914627107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawkes K. Human longevity: the grandmother effect. Nature. 2004;428(6979):128–129. doi: 10.1038/428128a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hawkes K, Smith KR. Do women stop early? Similarities in fertility decline in humans and chimpanzees. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1204:43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herndon JG, Paredes J, Wilson ME, et al. Menopause occurs late in life in the captive chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Age (Dordr) 2012;34(5):1145–1156. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9351-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill K, Boesch C, Goodall J, et al. Mortality rates among wild chimpanzees. J Hum Evol. 2001;40(5):437–450. doi: 10.1006/jhev.2001.0469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 19752011. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Humphrey PA. Prostate Pathology. Chicago, IL: ASCP Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang H, Zhu WJ, Li J, et al. Quantitative histological analysis and ultrastructure of the aging human testis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46(5):879–885. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson BD, Merz CN, Braunstein GD, et al. Determination of menopausal status in women: the NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13(8):872–887. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2004.13.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones KP, Walker LC, Anderson D, et al. Depletion of ovarian follicles with age in chimpanzees: similarities to humans. Biol Reprod. 2007;77(2):247–251. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Juengst ET, Binstock RH, Mehlman MJ, et al. Aging: antiaging research and the need for public dialogue. Science. 2003;299(5611):1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1083135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirkwood TB, Shanley DP. The connections between general and reproductive senescence and the evolutionary basis of menopause. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1204:21–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozik W. Arterial vasculature of ovaries in women of various ages in light of anatomic, radiologic and microangiographic examinations. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2000;46:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lacreuse A, Chennareddi L, Gould KG, et al. Menstrual cycles continue into advanced old age in the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Biol Reprod. 2008;79(3):407–412. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.068494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lahdenpera M, Lummaa V, Helle S, et al. Fitness benefits of prolonged post-reproductive lifespan in women. Nature. 2004;428(6979):178–181. doi: 10.1038/nature02367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lambalk CB, de Koning CH, Flett A, et al. Assessment of ovarian reserve: ovarian biopsy is not a valid method for the prediction of ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(5):1055–1059. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lass A. Assessment of ovarian reserve: is there still a role for ovarian biopsy in the light of new data? Hum Reprod. 2004;19(3):467–69. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laszczynska M, Brodowska A, Starczewski A, et al. Human postmenopausal ovary: hormonally inactive fibrous connective tissue or more? Histol Histopathol. 2008;23(2):219–226. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ledger W. Aging genital skin and hormone replacement therapy benefits. In: Farage M, Miller K, Maibach H, editors. Textbook of Aging Skin. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2010. pp. 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Levitis DA, Burger O, Lackey LB. The human post-fertile lifespan in comparative evolutionary context. Evol Anthropol. 2013;22(2):66–79. doi: 10.1002/evan.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Magalhaes JPD. Species selection in comparative studies of aging and antiaging research. In: Conn PM, editor. Handbook of Models for Human Aging. Waltham, MA: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE, National Center for Health Statistics . More Women Are Having Their First Child Later in Life. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health & Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.McVicar CM, O’Neill DA, McClure N, et al. Effects of vasectomy on spermatogenesis and fertility outcome after testicular sperm extraction combined with ICSI. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(10):2795–2800. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miller PB, Charleston JS, Battaglia DE, et al. An accurate, simple method for unbiased determination of primordial follicle number in the primate ovary. Biol Reprod. 1997;56(4):909–915. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod56.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller PB, Charleston JS, Battaglia DE, et al. Morphometric analysis of primordial follicle number in pigtailed monkey ovaries: symmetry and relationship with age. Biol Reprod. 1999;61(2):553–556. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.2.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mills SE. Histology for Pathologists. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muller MN, Wrangham RW. Mortality rates among Kanyawara chimpanzees. J Hum Evol. 2014;66:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Institutes of Health. Announcement of Agency Decision: Recommendations on the Use of Chimpanzees in NIH-Supported Research, June 26, 2013. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nichols SM, Bavister BD, Brenner CA, et al. Ovarian senescence in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):79–83. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nicosia SV. The aging ovary. Med Clin North Am. 1987;71(1):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Occhipinti K, Kutcher R, Rosenblatt R. Sonographic appearance and significance of arcuate artery calcification. J Ultrasound Med. 1991;10(2):97–100. doi: 10.7863/jum.1991.10.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osol G, Mandala M. Maternal uterine vascular remodeling during pregnancy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:58–71. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00033.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Owen C, Armstrong AY. Clinical management of leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(1):67–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ozkan S, Murk W, Arici A. Endometriosis and infertility: epidemiology and evidence-based treatments. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1127:92–100. doi: 10.1196/annals.1434.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prufer K, Munch K, Hellmann I, et al. The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes. Nature. 2012;486(7404):527–531. doi: 10.1038/nature11128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pühse G, Hense J, Bergmann M, et al. Bilateral histological evaluation of exocrine testicular function in men with obstructive azoospermia: condition of spermatogenesis and andrological implications? Hum Reprod. 2011;26(10):2606–2612. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Russo J, Rivera R, Russo IH. Influence of age and parity on the development of the human breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1992;23(3):211–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01833517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Russo J, Russo IH. Development of the human breast. Maturitas. 2004;49(1):2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sampson N, Untergasser G, Plas E, et al. The ageing male reproductive tract. J Pathol. 2007;211(2):206–218. doi: 10.1002/path.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scott PA, Provencher M, Guerin P, et al. Gestation-induced uterine vascular remodeling. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;550:103–123. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-009-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seppan P, Krishnaswamy K. Long-term study of vasectomy in Macaca radiata: histological and ultrasonographic analysis of testis and duct system. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2014;60(3):151–160. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2014.896957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Silva AE, Ocarino NM, Cassali GD, et al. Uterine leiomyoma in chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia. 2006;58(1):129–132. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sivridis E, Giatromanolaki A. Proliferative activity in postmenopausal endometrium: the lurking potential for giving rise to an endometrial adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57(8):840–844. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.014399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10(9):843–848. doi: 10.1089/152460901753285732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steiner MS, Couch RC, Raghow S, et al. The chimpanzee as a model of human benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1999;162(4):1454–1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Toft JD, 2nd, MacKenzie WF. Endometrial stromal tumor in a chimpanzee. Vet Pathol. 1975;12(1):32–36. doi: 10.1177/030098587501200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World population ageing 1950–2050. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WPA2009/WPA2009_WorkingPaper.pdf. Published December 2009. Accessed December 2015.

- 88.Videan EN, Fritz J, Heward CB, et al. The effects of aging on hormone and reproductive cycles in female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Comp Med. 2006;56(4):291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Videan EN, Fritz J, Heward CB, et al. Reproductive aging in female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Interdiscip Top Gerontol. 2008;36:103–118. doi: 10.1159/000137688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Videan EN, Satterfield WC, Buchl S, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of uterine leiomyomata in female chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Am J Primatol. 2011;73(7):665–670. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.vom Saal FS, Finch CE. Reproductive senescence: phenomena andmechanisms in mammals and selected vertebrates. Physiology of Reproduction. 1988;2:2351–2413. [Google Scholar]

- 92.vom Saal FS, Finch CE, Nelson JF. Natural history and mechanisms of reproductive aging in humans, laboratory rodents, and other selected vertebrates. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 1213–1314. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Walker ML, Anderson DC, Herndon JG, et al. Ovarian aging in squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) Reproduction. 2009;138(5):793–799. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Walker ML, Herndon JG. Menopause in nonhuman primates? Biol Reprod. 2008;79(3):398–06. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.068536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Williams GC. Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence. Evolution. 1957;11:398–411. [Google Scholar]