Abstract

The ability of Fe(II)-activated calcium peroxide (CaO2) to remove benzene is examined with a series of batch experiments. The results showed that benzene concentrations were reduced by 20 to 100% within 30 min. The magnitude of removal was dependent on the CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene molar ratio, with much greater destruction observed for ratios of 4/4/1 or greater. An empirical equation was developed to quantify the destruction rate dependence on reagent composition. The presence of oxidative hydroxyl radicals (HO•) and reductive radicals (primarily O2•−) was identified by probe compound testing and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) tests. The results of the EPR tests indicated that the application of CaO2/Fe(II) enabled the radical intensity to remain steady for a relatively long time. The effect of initial solution pH was also investigated, and CaO2/Fe(II) enabled benzene removal over a wide pH range of 3.0~9.0. The results of radical scavenging tests showed that benzene removal occurred primarily by HO• oxidation in the CaO2/Fe(II) system, although reductive radicals also contributed. The intermediates in benzene destruction were identified to be phenol and biphenyl. The results indicate that Fe(II)-activated CaO2 is a feasible approach for treatment of benzene in contaminated groundwater remediation.

Keywords: calcium peroxide, benzene, ferrous iron, reactive oxygen species

1. Introduction

Low molecular weight aromatic hydrocarbons such as BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes), which account for nearly 20% volume fraction in gasoline and other fuels [1–2], continue to be of great concern for environmental and human-health issues. BTEX contaminants have been widely detected in soil and groundwater due to discharges from chemical industries, accidental spills, and pipe/tank leaks. Numerous studies have reported on the potential risks to microorganisms, animals, plants [2–5] and humans [6–8] derived from exposure to BTEX contaminants. As a result, development and application of methods for remediation of BTEX contamination remains a focus of research.

The use of in-situ bioremediation for treatment of BTEX-contaminated sites has been well established, with both aerobic and anaerobic degradation approaches [9–13]. However, bioremediation is generally slow, and both aerobic and anaerobic technologies require strict redox conditions that limit their applications [14]. While aerobic biodegradation is typically more effective, the flux of oxygen in subsurface systems is often not adequate to support biodegradation, and supplementation is required.

Chemical oxidation is an alternative method to in-situ bioremediation that may be more time- and cost-effective in certain situations. Fenton’s reagent (a mixture of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and ferrous salt) has attracted much attention as an oxidant for in-situ use due to its strong, non-selective oxidation capability and low environmental impact. The Fenton reaction generates hydroxyl radical (HO•), which possesses a high oxidation potential (2.76 V) [15], and many studies have concluded that HO• is a strong and relatively indiscriminate oxidant that can react with most contaminants [16–17]. Several Fenton’s oxidation based technologies have been adapted for soil and groundwater remediation [18–20]. The results of many studies have shown that the traditional Fenton oxidant is relatively ineffective for subsurface applications due to the instability of H2O2 and issues with Fe availability. Therefore, solid H2O2 sources that can slow and control the release of H2O2 are of interest for in-situ applications.

Calcium peroxide (CaO2) is one effective solid-phase source of hydrogen peroxide, releasing H2O2 and Ca(OH)2 when dissolved in water via:

| (1) |

releasing a maximum of 0.47 g H2O2/g CaO2 [21]. Compared to traditional liquid H2O2, the H2O2 liberated from CaO2 is auto-regulated by the dissolution of CaO2, thus reducing the decomposition loss of H2O2. Ndjou’ou and Cassidy [22] observed that CaO2-based oxidation produced at least 20% greater degradation of contaminants compared to liquid H2O2. Several studies have reported the use of CaO2 for removal of various contaminants. Xu et al. [23] studied chemical oxidation of cable oil with solid CaO2, and the highest cable oil removal efficiency for CaO2 was 18% at pH 1.8; Goi et al. [24] applied CaO2 for the treatment of soil contaminated by polychlorinated biphenyls-containing electrical insulating oil, which resulting in nearly complete (96 ± 2%) oil removal; Zhang et al. [25] reported CaO2 alone was also effective for removing six phenolic endocrine disrupting compounds from waste activated sludge over the wide pH range of 2 to 12; and Li et al. [26] have demonstrated CaO2 can remove refractory organic contaminants effectively, which are non-biodegradable under ordinary anaerobic conditions. In addition, the removal of a wide variety of pollutants, including 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) [27], total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPHs) [22], polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [28], trichloroethene (TCE) [29], and tetrachloroethene (PCE) [30] have been also reported.

To date there has been minimal investigation of CaO2 for oxidative treatment of BTEX compounds. The reaction mechanisms and the dominant reactive oxygen radicals responsible for contaminant removal have yet to be studied. Therefore, the objectives of this research are to (1) evaluate the destruction of benzene in a CaO2/Fe(II) oxidation system; (2) identify the main reactive species contributing to benzene removal by using probe compounds, free-radical scavenging reagents, and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) tests; (3) establish an empirical mathematical model to quantify the reaction; (4) assess the impacts of solution pH; and (5) propose the mechanism of benzene destruction in the CaO2/Fe(II) system. It is anticipated that these experiments will provide fundamental support for BTEX-contaminated groundwater remediation using Fe(II)-activated CaO2.

2. Experiments

2.1 Materials

Ultrapure water (Milli-Q Classic DI, ELGA, Marlow, UK) was used for preparing the aqueous solutions. Benzene (99.7%) and calcium peroxide (CaO2, 75%) were provided by the Aladdin Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Carbon tetrachloride (CT, 99.5%), methanol (CH3OH, 99.9%), n-hexane (C6H14, 97%), and ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O, 99.5%) were purchased from the Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Isopropanol (C3H8O, IPA, 99.5%), trichloromethane (CHCl3, 99.0%), and nitrobenzene (NB, 99.0%) were purchased from the Shanghai Jingchun Reagent Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) was purchased from Sigma (Shanghai, China). H2SO4 (0.1 M) or NaOH (0.1 M) was used for solution pH adjustment.

2.2 Experiment design

The experiments were conducted using custom glass vessels with a fluid capacity of 250 mL and a jacket for temperature control at 20 ± 0.5°C. The solutions were mixed with a magnetic stirrer at moderate speed. Pure benzene was equilibrated with Milli-Q water and then diluted to the desired concentration. The initial concentration of benzene in all tests was set at 1.0 mM. All chemicals involved in the reactions (such as benzene, ferrous sulfate, etc.) except for CaO2 were completely dissolved in the reactor, and the reaction started as soon as the predetermined CaO2 dosage was added. Control reactors with no CaO2 added were used for each experiment treatment. The initial solution pH in all tests was unadjusted except for the specific experiment that investigated the influence of solution pH. For this case, the pH was adjusted before addition of Fe(II) and CaO2. 2.5-mL samples were collected from the reactor at the desired time and added to a headspace vial containing 1.0 mL methanol solution to stop further reaction and sealed for immediate analysis by headspace-gas chromatography (HS-GC).

Radical probe tests were performed to identify the reactive species involved in the reactions. For these tests, benzene was replaced by either NB (HO• probe) [31–32] or CT (O2•− probe) [33–34]. Additional details of the probe test are presented in the Supplementary Materials. EPR detection was conducted to confirm the primary radicals present in the CaO2/Fe(II) system. This test used DMPO to trap the radicals in solution. At the desired time intervals, samples (1.0 mL) were collected from the benzene destruction reactors and thoroughly mixed with 1.0 mL DMPO solution (8.84 mM) for 1 min. The mixed sample was then analyzed with the EPR instrument. In addition, radical scavenger tests were conducted to help characterize the dominant reactive species. The compounds IPA (HO• scavenger) [32] and CHCl3 (O2•− scavenger) [34] were used as radical scavengers and added to the benzene destruction solution to assess the impacts of HO• and O2•− radicals. Ethyl acetate was used in extracting products formed in benzene destruction, and the concentrated ethyl acetate was then analyzed by GC/MS. Additional details of the scavenger test are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Central composite designs (CCD) are multivariable, multilevel experimental procedures that analyze the interactions between variables and produce response equations. If the two variables are evaluated and represented on the x and y axis of a coordinate system, the results can be described by a response surface [e.g., 35]. To determine the optimum conditions for the CaO2/Fe(II) system, a CCD with two factors was applied in the present study (Table 1). Two variables (CaO2 concentration and Fe(II) concentration) were investigated in the CaO2/Fe(II) system for oxidation of benzene using CCD experiments. The variables Xi are coded as xi according to Eq. 2:

| (2) |

where Xi is the real value of the input variable, Xi0 is the value of Xi at the center point of the investigated area and the ΔXi is the step change. The response variable is fitted by a quadratic polynomial equation:

| (3) |

where Y is the response variable (the benzene destruction efficiency), xi and xj are the code values of the input variables, and β0, βi, βii and βj are the model coefficients.

Table 1.

Ranges and levels of the variables tested in the CCD

| Independent variables | Symbol | Actual values of the coded variable levels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| −1.41421 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 1.41421 | ||

| CaO2/mM | X1 | 2 | 3.17 | 6.00 | 8.83 | 10 |

| Fe(II)/mM | X2 | 2 | 3.17 | 6.00 | 8.83 | 10 |

2.3 Analytical methods

Benzene extract was analyzed using an Agilent HS-GC (Agilent 6890N, Palo Alto, CA, USA ) with a flame ionization detector (FID), an HP-5 column (30-m length, 0.32-mm I.D., 0.25-μm thickness), and an auto-sampler (COMBI-PLA, CTC, Switzerland). The CT and NB extracts were analyzed using an Agilent gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890A, Palo Alto, CA, USA ) with an electron capture detector (ECD), an auto-sampler (Agilent 7693), and a DB-VRX column (60 m length, 250 μm i.d., and 1.4 μm thickness). The intermediates formed in benzene destruction were identified by GC/MS (Agilent 6890/5973N). The free radicals were identified by EPR (EMX-8/2.7C, Bruker, Germany) using DMPO as a spin trap. The instrumental settings were as follows: field sweep: 100 G, microwave frequency: 9.866 GHz, microwave power: 2.016 mW, modulation amplitude: 1 G, conversion time: 40.96 ms, time constant: 163.84 ms, receiver gain: 3.17 X 104, and number of scans: 1. The pH was measured with a pH meter (Mettler-Toledo DELTA 320, Greifensee, Switzerland). The other specific conditions for the analyses can be found in our previously published paper [36].

The benzene destruction data were used to develop regression equations and modeled by using the software MINITAB. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the model. The resulted regression equations were plotted response surfaces using MINITAB software.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Effectiveness of CaO2/Fe(II) process for benzene destruction

The experiments were performed with a fixed benzene concentration (1.0 mM) at various CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene molar ratios ranging from 1/1/1 to 10/10/1, and the results are presented in Fig. 1. The results from the control tests (absence of CaO2) showed less than 7% benzene loss, likely by volatilization. CaO2 or Fe(II) alone did not remove benzene in this study, which indicates that only Fe(II)-catalyzed CaO2 can generate the reactive species responsible for benzene destruction (Supplementary material, Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Benzene destruction in the CaO2/Fe(II) system at different CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene molar ratios ([Benzene]0 = 1.0 mM).

As shown in Fig. 1, 26%, 48%, 89%, 100% and 98% of benzene was removed in 30 min at CaO2/Fe(II)/benzene molar ratios of 1/1/1, 2/2/1, 4/4/1, 8/8/1, and 10/10/1, respectively. It is clear that benzene destruction was enhanced with increasing dosages of CaO2 and Fe(II). The magnitude of benzene destruction approximately doubles with a doubling of the reactant concentrations up to a molar ratio of 4/4/1, at which point close to complete destruction is attained.

In addition, rapid benzene destruction was observed within the first 5 min, and the destruction became much slower in the remaining reaction time. This may be due to the fast generation of reactive species after CaO2 was added into the reactor. The decomposition of CaO2 produced H2O2 and this supported the rapid reaction with Fe(II) for generating reactive species within a short time period. Once CaO2 was induced by Fe(II) along with the generation of reactive species, Fe(II) was oxidized into Fe(III), which soon caused a shortage of Fe(II). A rapid accumulation of Fe(III) accelerated the precipitation of Fe(OH)3, and the lack of Fe(II) impeded the radical propagation cycle, thus slowing down the benzene destruction.

Tawabini reported thatd benzene could be degraded more than 95% within 5 min by a UV/H2O2 process [37]; Daifullah and Mohamed also reported over 90% benzene degradation in 10 min of UV irradiation with the presence of H2O2 [38]; Liang et al. [39] reported the activated persulfate (PS) anion (S2O82−) could remove nearly 70% benzene at PS/Fe(II)/benzene molar ratio of 20/20/1 in 80 min. Compared to the above techniques, the CaO2/Fe(II) system is a feasible option in benzene destruction.

3.2 Detection of free radicals by EPR

To identify the reactive species, a series of tests were conducted with probes, scavenger compounds, and EPR for the detection of radicals. All of the experiments were designed and performed based on the hypothesis that CaO2/Fe(II) is a Fenton-like process. The probe and scavenging experiment results are listed in Supplementary Materials. The acquired probe-tests results (Fig. S1) demonstrate the presence of HO• and O2•−, suggesting that CaO2 is a viable alternative as a Fenton-like system. EPR detection was conducted to further confirm the radicals present in the CaO2/Fe(II) system. Fig. 2a shows the radical intensity variation and Fig. 2b presents the typical EPR spectrum of the CaO2/Fe(II) system.

Fig. 2.

(a)The intensity of HO• versus reaction time in the CaO2/Fe(II) system; (b) EPR spectra at the reaction time of 90 s ([CaO2]0 = 4.0 mM, [Fe(II)]0 = 4.0 mM; peaks associated with the presence of DMPO-OH are indicated with↓).

A DMPO-OH adduct was observed in the EPR spectra. The EPR spectrum, which has a specific quartet spectrum with peak height ratios of 1:2:2:1, indicated the formation of HO•. The results are consistent with other research [40]. The EPR detection, together with the results of the scavenging tests (Fig. S2), indicated that HO• is the predominant radical in the CaO2/Fe(II) system. However, the peaks of O2•− was not confirmed during the EPR analyses, which could be attributed to the low intensity of O2•− and the complicated solution composition in the CaO2/Fe(II) system.

3.3 Effect of CaO2 and Fe(II) dosages on benzene destruction

The effect of CaO2 and Fe(II) dosage corresponding to various CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene molar ratios on benzene destruction performance was investigated, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. The first set of experiments was performed by fixing Fe(II) at 4 mM while varying the CaO2 concentration from 2 to 8 mM in order to explore the effect of CaO2 dosage on benzene removal (Fig. 3a). With the increase in the initial CaO2 dosage from 2 to 4 mM, the benzene destruction rate increased from 80% to 89% in 30 min. However, excessive CaO2 decreased the benzene destruction efficiency to 44% over the same reaction time when the initial CaO2 concentration was increased to 8 mM.

Fig. 3.

Effect of (a) CaO2 dosage and (b) Fe(II) dosage on benzene destruction ([Benzene]0 = 1.0 mM). Values in the legend represent different CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene molar ratios.

With an increase in CaO2 dosage, the generation of H2O2 was increased and thus the production of radicals was enhanced. As a result, benzene removal increased. However, an elevation in solution pH was observed; the final solution pH levels increased to 8.9 and 11.6 when the CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene molar ratios were 4/4/1 and 8/4/1, respectively. It was also noted that the dissolution of CaO2 could produce Ca(OH)2 (Eq. 1) and then increase the solution pH, which imparts a negative effect on the Fenton reaction [41]. Moreover, the excessive CaO2 generated excessive H2O2, which in turn scavenged the reactive species via the reaction in Eq. 4 [15]:

| (4) |

It is clear that the solution pH was a significant factor in the CaO2/Fe(II) system and will be discussed in a later section of this study.

The second set of experiments was performed by fixing CaO2 at 4 mM while varying the Fe(II) concentration from 2 to 8 mM to explore the effect of Fe(II) dosage on benzene removal (Fig. 3b). It is apparent that the increase in Fe(II) dosage accelerated the oxidation of benzene. The benzene removal increased from 36% to 89% when the initial Fe(II) dosage increased from 2 to 4 mM. Conversely, an increase in the Fe(II) concentration to 8 mM did not enhance efficiency anymore. This result could be due to the reactions shown in Eqs. 5 and 6. Although an increased Fe(II) dosage could lower the solution pH (the final solution pH was 4.8 at the molar ratio of 4/8/1) and benefit benzene destruction, excessive Fe(II) could also scavenge HO• (Eq. 6) [42] and result in reduced removal.

| (5) |

| (6) |

Northup [30] also reported that the yield of H2O2 and the dissolution rate of CaO2 increased with the decreasing of solution pH. The increased Fe(II) dosage could lower the solution pH and accelerated the release of H2O2 from CaO2. Therefore, Fe(II) not only participated in the reaction with H2O2, but also promoted the release of H2O2 from CaO2 by decreasing the solution pH. At an optimal molar ratio of CaO2/Fe(II), the iron could accelerate the release of H2O2 as well as activate the released H2O2, thereby enhancing HO• radicals generation at a steady rate as shown in Fig. 2.

3.4 A mathematical model for the CaO2/Fe(II) system

To better understand the influence of the identified variables on the destruction of benzene in the CaO2/Fe(II) system, benzene removal was used as the response variable for the RSM. By fitting the values of benzene removal in Table S1, a quadratic polynomial model was derived as Eq. 7:

| (7) |

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) for Eq. 7 is shown in Table S2. The P-value of the model is less than 0.05, indicating that the model is significant. A high correlation coefficient (R2) of 0.980 suggests a good agreement between the experimental values and the model predicted values. The ANOVA revealed a significant interaction effect of the concentration of CaO2 and Fe(II) on the destruction kinetics of benzene (F = 33.67; P < 0.05). Fig. 4 is the response surface graph of removal values of benzene showing the influence of the concentration of CaO2 and Fe(II). It can be seen that the optimum molar ratio of CaO2 and Fe(II) close to 1:1. The response surface shows that the optimum conditions for benzene destruction were 8.0 mM CaO2 and 8.0 mM Fe(II) in this study.

Fig. 4.

Response surface for benzene destruction in the CaO2/Fe(II) system (Isoresponselines represent percent oxidation).

3.5 Effect of initial solution pH on benzene treatment

Benzene destruction in the CaO2/Fe(II) system for a pH range of 3.0~11.0 is shown in Fig. 5. Benzene removal surpassed 80% within 5 min when the initial solution pH ranged from 3.0 to 9.0, whereas the destruction was less than 60% when the initial solution pH was 11.0. Therefore, pH appears to have a significant impact on benzene destruction in the CaO2/Fe(II) system when it exceeds ~9. Greater destruction at lower solution pH is consistent with existing literature [25, 36, 43].

Fig. 5.

Effect of initial solution pH on benzene destruction in the CaO2/Fe(II) system ([Benzene]0 = 1.0 mM, [CaO2]0 = 4.0 mM, [Fe(II)]0 = 4.0 mM, initial solution pH = 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, 9.0, 11.0).

The Fe(II) and H2O2 speciation are strongly influenced by the solution pH in the conventional Fenton reaction. The elevation of solution pH facilitates the precipitation of Fe(III) in the form of Fe(OH)3, thus impeding radical propagation. This drawback was also observed for the CaO2/Fe(II) system. In addition, CaO2 dissolution is significantly influenced by the solution pH [30–31], thus the generation of H2O2 in the CaO2/Fe(II) system was constrained by the solution pH, resulting in the decrease of HO• generation and benzene destruction. When the pH was less than 10.0, CaO2 mainly released H2O2 via Eq. 1; but when the pH increased to 11.0, CaO2 mainly produced Ca(OH)2 and O2 through Eq. 8 [29–30].

| (8) |

Hence, the release of H2O2 in the CaO2/Fe(II) system can be regulated by adjusting the pH. These results suggest that CaO2-based radical generation is viable over a wide range of pH, which is a significant advantage compared to the conventional Fenton reaction.

Based on the benzene removal pattern, benzene destruction is treated as a second-order reaction [44], which can be described as follows:

| (9) |

It can then be modified as:

| (10) |

where C0 is the initial benzene concentration in solution (mM); Ci is the benzene concentration at time t (mM); and t is the reaction time (min); kobs is the second-order reaction rate constant that represents the overall rate of benzene destruction by a variety of oxidizing or reducing species (e.g., HO• and O2•−) generated in the system (M−1 min−1) under various initial solution pH levels, and the R2 values are summarized in Table 2. It is observed that kobs increased from 0.042 to 0.21 M−1 min−1 (0.0007 to 0.0035 M−1 s−1) with a decrease in the initial solution pH from 11.0 to 3.0. Due to the complicated composition of groundwater, the impact of changes in pH on benzene destruction should be investigated in more detail. This will be a focus in a future study.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters in benzene destruction under various pHs

| pH | Operational conditions | kobs (M−1 s−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene = 4/4/1 ([Benzene]0 =1.0 mM) |

0.0035 | 0.9667 |

| 5.0 | 0.0025 | 0.8885 | |

| 7.0 | 0.0022 | 0.9254 | |

| 9.0 | 0.0023 | 0.9525 | |

| 11.0 | 0.0007 | 0.7676 |

3.6 The mechanism of benzene destruction

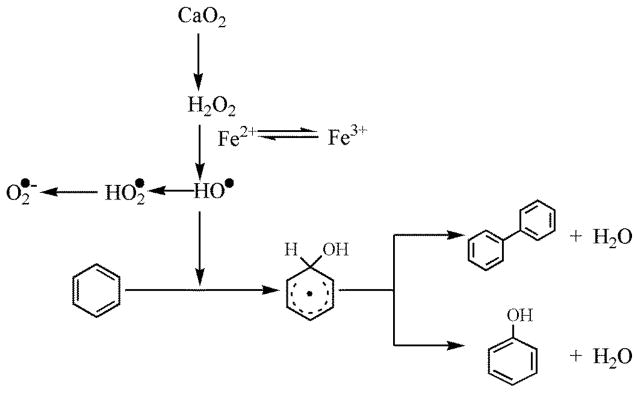

Phenol and biphenyl were identified to be the major intermediates in benzene destruction. As shown in Fig. S1, benzene removal was significantly inhibited when IPA was present. The final benzene removal decreased from 89% to 22% when IPA was added, indicating that HO• is the dominant reactive species in the CaO2/Fe(II) system. As for scavenging O2•−, the benzene removal decreased from 89% to 77% in the presence of chloroform. The inhibition of benzene destruction indicated that a certain amount of O2•− was generated in the reactions and contributed to benzene destruction to some extent. Based on the experimental results, HO• is the dominant reactive species, and possible benzene destruction pathways are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Proposed benzene destruction pathway in the CaO2/Fe(II) system.

CaO2 released H2O2 when dissolved in water, and the liberated H2O2 reacted with Fe2+ producing HO•. The produced HO• immediately abstracted hydrogen atom from benzene ring to form an unstable intermediate, which is presumed to be phenyl radical [45–46]; then phenol was produced through dehydration, and biphenyl formed after dimerization and dehydration. Other possible intermediates [45] were not identified by GC/MS.

4. Conclusions

This is an initial study that investigated the efficiency of benzene destruction by Fe(II)–activated CaO2 in aqueous solution. The experimental results indicated that the CaO2/Fe(II) system has the ability to remove benzene. Benzene destruction performance was related to the molar ratio of CaO2/Fe(II)/Benzene whose optimum ratio was found to be 4/4/1. An empirical equation was developed based on the experimental data. The probe compound experiments clearly identified the generation of the reactive species, namely, HO• and O2•−, in the CaO2/Fe(II) system. Furthermore, free radical scavenger tests further demonstrated that HO• was the dominant active species responsible for benzene removal and that O2•− partly contributed to the destruction. EPR tests also indicated that the application of CaO2/Fe(II) enabled the radical intensity to remain steady for a relatively long time. The effect of the initial solution pH was investigated, and the results showed that CaO2 enabled a high degree of benzene removal at a pH range of 3.0~9.0, with reduced degree of destruction at higher pH. Phenol and biphenyl were identified as the major intermediate products in benzene destruction. In summary, the CaO2/Fe(II) system is a feasible technique for the destruction of benzene.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41373094 and 51208199), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015M570341) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (222201514339 and 22A201514057). The contributions of Mark Brusseau were supported by the NIEHS Superfund Research Program (P42 ES04940).

References

- 1.American Petroleum Institute. Health and Environmental Sciences Departmental Report 4395. Washington, DC: 1985. Laboratory Study on Solubilities of Petroleum Hydrocarbon in Groundwater. [Google Scholar]

- 2.An YJ. Toxicity of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX) mixtures to Sorghum bicolor and Cucumis sativus. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2004;72:1006–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00128-004-0343-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campo P, Waniusiow D, Cossec B, Lataye R, Rieger B, Cosnier F, Burgart M. Toluene-induced hearing loss in phenobarbital treated rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahy A, Lethbridge G, Earle R, Ball AS, Timmis KN, McGenity TJ. Effects of long-term benzene pollution on bacterial diversity and community structure in groundwater. Environ Microbial. 2005;7:1192–1199. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng P, Lee JW, Sichani HT, Ng JC. Toxic effects of individual and combined effects of BTEX on Euglena gracilis. J Hazard Mater. 2015;284:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badham HJ, Winn LM. Investigating the role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in benzene-initiated toxicity in vitro. Toxicology. 2007;229:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.López E, Schuhmacher M, Domingo JL. Human health risks of petroleum-contaminated groundwater. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2008;15:278–288. doi: 10.1065/espr2007.02.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin RJ, Van Mouwerik M, Stevens L, Seese MD, Basham W. Environmental contaminants encyclopedia entry for BTEX and BTEX compounds. National Park Service; Colorado: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salanitro JP, Wisniewski HL, Byers DL, Neaville CC, Schroder RA. Use of aerobic and anaerobic microcosms to assess BTEX biodegradation in aquifers. Groundwater Monit Rem. 1997;17:210–221. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coates JD, Chakraborty R, McInerney MJ. Anaerobic benzene biodegradation—a new era. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:621–628. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01378-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakraborty R, Coates JD. Anaerobic degradation of monoaromatic hydrocarbons. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;64:437–446. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jindrova E, Chocova M, Demnerova K, Brenner V. Bacterial aerobic degradation of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene. Folia Microbiol. 2002;47:83–93. doi: 10.1007/BF02817664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Naas MH, Acio JA, Telib AEE. Aerobic biodegradation of BTEX: Progresses and Prospects. J Environ Chem Eng. 2014;2:1104–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farhadian M, Vachelard C, Duchez D, Larroche C. In situ bioremediation of monoaromatic pollutants in groundwater: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:5296–5308. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walling C. Fenton’s reagent revisited. Acc Chem Res. 1975;8:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Che H, Bae S, Lee W. Degradation of trichloroethylene by Fenton reaction in pyrite suspension. J Hazard Mater. 2011;185:1355–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorfman LM, Adams GE. Reactivity of the hydroxyl radical in aqueous solutions. National Bureau of Standards; Washington, DC: 1973. pp. 1–59. Report no. NSRDS-NBS-46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith BA, Teel AL, Watts RJ. Destruction of trichloroethylene and perchloroethylene DNAPLs by catalyzed H2O2 propagations. J Environ Eng. 2009;135:535–543. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2015.1019806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H, Hong HJ, Jung J, Kim SH, Yang JW. Degradation of trichloroethylene (TCE) by nanoscale zero-valent iron (nZVI) immobilized in alginate bead. J Hazard Mater. 2010;176:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.11.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishikiori H, Masaru F, Tsuneo F. Degradation of trichloroethylene using highly adsorptive allophane–TiO2 nanocomposite. Appl Catal, B. 2011;102:470–474. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vol’nov II. Peroxides, superoxides, and ozonides of alkali and alkaline earth metals. New York: Plenum Press; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ndjou’ou AC, Cassidy D. Surfactant production accompanying the modified Fenton oxidation of hydrocarbons in soil. Chemosphere. 2006;65:1610–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, Pancras T, Grotenhuis T. Chemical oxidation of cable insulating oil contaminated soil. Chemosphere. 2011;84:272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goi A, Viisimaa M, Trapido M, Munter R. Polychlorinated biphenyls-containing electrical insulating oil contaminated soil treatment with calcium and magnesium peroxides. Chemosphere. 2011;82:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang A, Wang J, Li YM. Performance of calcium peroxide for removal of endocrine-disrupting compounds in waste activated sludge and promotion of sludge solubilization. Water Res. 2015;71:125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li YM, Wang J, Zhang A, Wang L. Enhancing the quantity and quality of short-chain fatty acids production from waste activated sludge using CaO2 as an additive. Water Res. 2015;83:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arienzo M. Degradation of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene in water and soil slurry utilizing a calcium peroxide compound. Chemosphere. 2000;40:331–337. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogan BW, Trbovic V, Paterek JR. Inclusion of vegetable oils in Fenton’s chemistry for remediation of PAH-contaminated soils. Chemosphere. 2003;50:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang X, Gu X, Lu S, Miao Z, Xu M, Qiu Z, Sui Q. Degradation of trichloroethylene in aqueous solution by calcium peroxide activated with ferrous ion. J Hazard Mater. 2015;284:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Northup A, Cassidy D. Calcium peroxide (CaO2) for use in modified Fenton chemistry. J Hazard Mater. 2008;152:1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolanov Y, Prikhodchenko PV, Medvedev AG, Pedahzur R, Lev O. Zinc dioxide nanoparticulates: a hydrogen peroxide source at moderate pH. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:8769–8774. doi: 10.1021/es4020629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O-) in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1988;17:513–886. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu M, Gu X, Lu S, Qiu Z, Sui Q. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species for 1, 1, 1-Trichloroethane Degradation in a Thermally Activated Persulfate System. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2014;53:1056–1063. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teel AL, Watts RJ. Degradation of carbon tetrachloride by modified Fenton’s reagent. J Hazard Mater. 2002;94:179–189. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3894(02)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teel AL, Warberg CR, Atkinson DA. Comparison of mineral and soluble iron Fenton’s catalysts for the treatment of trichloroethylene. Water Res. 2001;35:977–84. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(00)00332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu X, Gu X, Lu S, Miao Z, Xu M, Zhang X, Qiu Z, Sui Q. Benzene depletion by Fe2+-catalyzed sodium percarbonate in aqueous solution. Chem Eng J. 2015:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tawabini BS. Simultaneous Removal of MTBE and Benzene from Contaminated Groundwater Using Ultraviolet-Based Ozone and Hydrogen Peroxide. Int J Photoenergy. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/452356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daifullah AHAM, Mohamed MM. Degradation of benzene, toluene ethylbenzene and p-xylene (BTEX) in aqueous solutions using UV/H2O2 system. J Chem Technol Biot. 2004;79:468–474. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang C, Huang CF, Chen YJ. Potential for activated persulfate degradation of BTEX contamination. Water Res. 2008;42:4091–4100. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miao Z, Gu X, Lu S, Dionysiou DD, Al-Abed SR, Zang X, Wu X, Qiu Z, Sui Q, Danish M. Mechanism of PCE oxidation by percarbonate in a chelated Fe(II)-based catalyzed system. Chem Eng J. 2015;275:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lemaire J, Croze V, Maier J, Simonnot MO. Is it possible to remediate a BTEX contaminated chalky aquifer by in situ chemical oxidation? Chemosphere. 2011;84:1181–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuglik Z, Pawełzagórski Z. Pulse radiolysis of neutral iron (II) solutions: oxidation of ferrous ions by OH radicals. Radiat Phys Chem. 1977;17:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pignatello JJ, Oliveros E, MacKay A. Advanced oxidation processes for organic contaminant destruction based on the Fenton reaction and related chemistry. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2006;36:1–84. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang L, Zhao Y, Ma B. Treatment of BTEX in groundwater by Fenton’s and Fenton-like oxidation reaction and the kinetics. Chin J Environ Eng. 2011;5:992–996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eberhardt MK. Radiation Induced Homolytic Aromatic Substitution. II. Hydroxylation And Phenylation Of Benzene. J Phys Chem. 1974:1795–1797. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lindsay Smith JR, Norman ROC. Hydroxylation. Part I. The oxidation of benzene and toluene by Fenton’s reagent. J Chem Soc. 1963:2897–2905. 539. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.