Abstract

This research examined endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones. Participants were 1235 females and 398 males from the Growing Up Today Study, ages 22 to 29 years, who endorsed a sexual minority orientation (lesbian/gay, bisexual, mostly heterosexual) or reported same-gender sexual behavior (heterosexual with same-gender sexual experience). An online survey measured current sexual orientation and endorsement and timing (age first experienced) of five sexual orientation developmental milestones: same-gender attractions, other-gender attractions, same-gender sexual experience, other-gender sexual experience, and sexual minority identification. Descriptive analyses and analyses to test for gender and sexual orientation group differences were conducted. Results indicated that females were more likely than males to endorse same-gender attraction, other-gender attraction, and other-gender sexual experience, with the most gender differences in endorsement among mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience. In general, males reached milestones earlier than females, with the most gender differences in timing among lesbian and gay individuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience. Results suggest that the three sexual minority developmental milestones may best characterize the experiences of lesbians, gay males, and female and male bisexuals. More research is needed to understand sexual orientation development among mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience.

Keywords: sexual minority development, sexual orientation, sexual identity development, developmental milestones

Sexual orientation development among sexual minorities (non-heterosexual individuals) has received increased attention in recent decades as researchers have investigated the experiences of sexual minorities beyond psychopathology. Initially, researchers proposed that sexual orientation developed in a linear fashion for sexual minorities and that all sexual minorities progressed similarly through specific stages of development, beginning in adolescence (Cass, 1979; Meyer & Schwitzer, 1999). More recently, researchers have suggested an alternative developmental trajectories approach that acknowledges the potential for group-level heterogeneity in sexual orientation development (Floyd & Stein, 2002; Author et al., 2008; Worthington & Reynolds, 2009). Sexual minority researchers have also highlighted the importance of considering sexual minorities beyond the heterosexual and lesbian/gay dichotomy to include bisexuals (e.g., Klein, 1993), mostly heterosexuals (e.g., Author et al., 2007; Savin-Williams & Vrangalova, 2013), and completely heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience (e.g., Cochran & Mays, 2007). As the majority of research on sexual orientation developmental milestones has been conducted on lesbian and gay individuals, little is known about whether these milestones also apply to other sexual minority subgroups. The current study examined endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones among female and male young adults across a range of sexual minority orientations.

Sexual orientation is conceptualized as multidimensional, primarily comprised of attractions, sex/gender of sexual partners, and sexual orientation identity (IOM, 2011; Klein, Sepekoff, & Wolf, 1985; Author et al., 2014). Sexual orientation developmental milestones may include first experiencing attractions toward a person of the same or another gender and first engaging in sexual behavior with a person of the same or another gender. The major developmental milestones for sexual minorities include first experiencing same-gender attractions and first engaging in sexual behavior with same-gender individuals, as well as first identifying as a sexual minority. Other related sexual minority developmental milestones include first questioning sexual orientation (Diamond, 2003; Author et al., 1996), first disclosing a sexual minority identity to others (D’Augelli, 2006), and first same-gender relationship (Garnets & Kimmel, 1993). These milestones have often been referred to as “sexual identity [italics added for emphasis] developmental milestones,” following Erikson’s (1968) identity development theory. However, we use the term “sexual orientation [italics added for emphasis] developmental milestones” throughout this paper to avoid the assumption that developmental milestones refer only to sexual orientation identity, rather than encompassing multiple dimensions of sexual orientation (attractions, sex/gender of sexual partners, and sexual orientation identity).

The application of life course theory to sexual orientation development proposes that an individual understands their sexual desire in the context of a specific cultural model of human sexuality that then leads to sexual behaviors and the assumption of a sexual orientation identity (Hammack, 2005). In the United States, individuals develop their sexual orientation within the context of heteronormativity, in which heterosexuality is perceived as the default. Although it is important to recognize that heterosexual individuals also undergo a process of sexual orientation development (Morgan, Steiner & Thompson, 2010; Morgan & Thompson, 2011; Worthington, Savoy, & Dillon, 2002), the process of sexual minority development differs in that sexual minority individuals face stigma related to sexual minority orientation, which may affect the process of forming a minority sexual orientation. It should be noted that stigma related to sexual minority orientation may be changing over time. A study that analyzed trends in U.S. opinion polls about same-gender orientation found that opinions toward sexual minorities have become more positive over time (Hicks & Lee, 2006). For example, in 2001 when data were collected for the current study and participants were young adults ages 22–29 years, 52% of adults surveyed believed that “homosexuality should be considered an acceptable alternative lifestyle” compared to 44% in 1996 and 38% in 1992, when participants in the current study were adolescents. However, 43% of adults surveyed in 2001 believed homosexuality was unacceptable, suggesting that stigma related to sexual minority orientation was still quite present.

Previous research on sexual orientation development among sexual minorities has emphasized the timing of sexual minority developmental milestones, demonstrating that sexual minorities typically reach milestones during adolescence, with some milestones occurring in early adolescence (e.g., same-gender attractions) and other milestones occurring in late adolescence (e.g., coming out to other as a sexual minority) (D’Augelli, 2006; Floyd & Bakeman, 2006; Author, 2014), with similar patterns across generations (Author et al., 2011). Some research has found differences by race and ethnicity in the timing of sexual minority development (Dubé & Savin-Williams, 1999; Parks, Hughes, & Matthews, 2004), but these findings have not been confirmed by other research (Author et al., 2004).

Previous research on sexual orientation developmental milestones has also examined the order in which milestones occur. D’Augelli (2006) found that both female and male sexual minority youth typically experienced same-gender attractions before having a same-gender sexual experience, but that some participants self-identified as a sexual minority prior to having a same-gender sexual experience, whereas other participants self-identified as a sexual minority after having a same-gender sexual experience. This study examined gender differences in milestone timing and order, but did not separately examine the experiences of lesbian/gay vs. bisexual individuals.

One limitation of previous research on sexual minority development is that studies are often limited to individuals who identify as lesbian or gay (e.g., Cass, 1979), rather than including the experiences of individuals with attractions to or sexual behavior with individuals of more than one gender (e.g., bisexual or mostly heterosexual). In addition, studies of sexual minority development that have included bisexuals have failed to consider their experiences independently from lesbian and gay individuals (D’Augelli, 2006; Floyd & Bakeman, 2006). Mostly heterosexuals in particular may have unique developmental trajectories that are marked by continuous identity exploration (Savin-Williams & Vrangalova, 2007; Thompson & Morgan, 2008). Emphasis on the timing of developmental milestones is problematic without first considering whether all sexual minority groups experience such milestones in the first place. In addition to timing, the current study will examine endorsement of sexual orientation developmental milestones across a range of sexual minority orientations.

Gender differences in sexual minority development are another important consideration. Previous research has demonstrated that male sexual minorities typically reach sexual orientation developmental milestones earlier than female sexual minorities (D’Augelli, 2006; Floyd & Bakeman, 2006; Author, 2014; Author et al., 1996). Such gender differences might also be found within specific sexual minority groups, such as bisexuals or mostly heterosexuals. The timing of sexual minority developmental milestones is important to consider because of the association between timing and other risk factors; for instance, earlier timing of milestones is associated with homelessness among sexual minority youth (Author et al., 2012). Some risk factors associated with timing of sexual minority developmental milestones may be gendered, such as childhood maltreatment, although these associations have not yet been examined in samples that included more than one gender. This highlights the importance of examining gender differences in the timing of milestones. Unfortunately, little research has addressed the question of whether endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones differ by both gender and sexual orientation subgroup.

The current study examined endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones, using data from the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), a prospective cohort of adolescents and young adults in the United States. The GUTS sample is unique for studying sexual minorities, because participants were not recruited based on sexual minority status, thus yielding a more representative sample. The aim of this study was to describe the pattern of endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones by gender and sexual orientation group, with particular emphasis on exploring unique experiences across the sexual minority spectrum.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants in this study were 1235 females and 398 males who endorsed a sexual minority orientation or reported same-gender sexual behavior in the 2010 wave of GUTS (Total N = 5630 females and 3060 males), a prospective cohort of 16,875 children of women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study II (Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School). Initial recruitment procedures are reported elsewhere (Field, Camargo, Taylor, Berkey, Frazier, Gillman et al., 1999). Youth ages 9 to 14 years were originally enrolled in GUTS in 1996 and followed annually or biennially. Data for the current study came from the 2010 wave when participants were ages 22 to 29 years. Other demographic information for the sample is reported in Table 1. This research was approved by the [blinded] Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Characteristics for Female (N=1235) and Male (N=398) Young Adults, Ages 22 to 29 Years, in the Growing Up Today Study who Reported Any Same-Gender Orientation in 2010

| Measure | Total | Females | Males | Females vs. Males (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, M/SD) | 25.3 (1.6) | 25.3 (1.6) | 25.4 (1.7) | 0.66 |

| Current sexual orientation identity (%, n) | <.001 | |||

| Lesbian/gay | 11.1 (182) | 6.8 (84) | 24.6 (98) | |

| Bisexual | 8.8 (143) | 10.3 (127) | 4.0 (16) | |

| Mostly heterosexual | 59.0 (964) | 62.8 (776) | 47.2 (188) | |

| Heterosexual with same-gender sexual experience | 21.1 (344) | 20.1 (248) | 24.1 (96) | |

| Race/ethnicity (%, n) | 0.41 | |||

| White | 91.2 (1484) | 91.5 (1125) | 90.2 (359) | |

| Non-white | 8.8 (143) | 8.5 (104) | 9.8 (39) | |

| Household income (%, n) | 0.11 | |||

| Low income <$50k | 13.0 (177) | 13.8 (143) | 10.4 (34) | |

| High income >$50k | 87.0 (1183) | 86.2 (891) | 89.6 (292) |

Note. Reported p-values are from chi-square tests and t-tests. Household income is from the mothers’ report of pre-tax annual household income in 2001. Percentages do not total to 100 for some variables due to missing data.

Measures

Sex/gender

Sex/gender was assessed in 1996 as female or male. Participants who reported a different sex/gender from 1996 in a wave prior to 2010 (n = 1) were excluded from the current study.

Sexual orientation

Sexual orientation was assessed in 2010 with the item “Which of the following best describes your feelings?” and the following response options: completely heterosexual (attracted to persons of the opposite sex), mostly heterosexual, bisexual (equally attracted to men and women), mostly homosexual, completely homosexual (gay/lesbian, attracted to persons of the same sex), and not sure. For the current study, participants who responded not sure were excluded from the analyses (n = 26) and participants who responded mostly homosexual and completely homosexual were combined into a lesbian/gay group due to small sample sizes. For participants who responded completely heterosexual, a second item measuring lifetime sexual experiences with females or males (“During your lifetime, have you ever had sexual contact with a female/male?”) was used to form the category heterosexual with same-gender sexual experience. Thus, four sexual orientation subgroups were examined in the current study: lesbian/gay, bisexual, mostly heterosexual, and heterosexual with (lifetime) same-gender sexual experience.

Sexual orientation developmental milestones

Sexual orientation developmental milestones were assessed in 2010 with five items adapted from the Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule–Youth (SERBAS-Y; Meyer-Bahlburg, Ehrhardt, Exner, & Gruen, 1994): 1) “During your life, have you ever identified yourself as ‘mostly heterosexual,’ bisexual, or lesbian or gay?” 2) “During your lifetime, have you ever been sexually attracted to females?” 3) During your lifetime, have you ever been sexually attracted to males 4) “During your lifetime, have you ever had sexual contact with a female?” and 5) During your lifetime, have you ever had sexual contact with a male?” Items 2–5 assessed sexual attraction and sexual contact separately for the same and other gender. Items 4 and 5 were the same items used to form the sexual orientation subgroup category heterosexual with same-gender sexual experience. Response options for each milestone question were yes and no. For participants providing a yes response, age in years was assessed for when each milestone was first experienced. Reliability and validity of the SERBAS-Y have been found in previous research (Author et al., 2004; Author et al., 2012; Author et al., 2009; Schrimshaw, Rosario, Meyer-Bahlburg, & Scharf-Matlick, 2006).

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted to assess the frequency of endorsement and timing (age first experienced) of sexual orientation developmental milestones by gender and sexual orientation group. For endorsement, frequency and percentage were computed for each milestone. Then, frequency and percentage were computed to determine the overlap of endorsement of all possible combinations of two and three sexual minority developmental milestones (same-gender attractions, same-gender sexual experience, and sexual minority identification) for each subgroup; for example, the frequency of heterosexual females with same-gender sexual experience who endorsed both a sexual minority identity and same-gender attraction in their lifetime. Overlap percentages were computed only among participants who provided an answer (yes or no) to all three sexual minority milestone questions. Age of milestone was systematically missing if a participant did not endorse having experienced a milestone as participants were not asked to report an age for milestones they did not endorse. In addition, age of milestone was missing if participants left blank the age of experiencing a milestone but endorsed having experienced the milestone.

Analyses were also conducted to test for differences in milestone endorsement and timing by gender and sexual orientation group. To test for gender differences within each sexual orientation group, chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests were conducted for endorsement (yes, no) and t-tests were conducted for timing (mean age) of each milestone. To test for sexual orientation group differences within females and males, chi-square tests and ANOVAs were conducted for endorsement (yes, no) and timing (mean age) of each milestone, respectively. Finally, for each gender group, differences between milestones in mean age of attainment were tested by fitting mixed models with milestone as the predictor and the age at which the milestone was reached as the outcome. These models included a random intercept term to account for multiple observations (age of each milestone) for each individual. No covariates were included.

Results

Endorsement of Sexual Orientation Developmental Milestones

Females and males

Gender differences in milestone endorsement were examined without regard to sexual orientation subgroups (Table 2) and within each sexual orientation group (Table 3). Females were more likely than males to endorse same-gender and other-gender attractions and other-gender sexual experience. Among lesbian and gay individuals, females were more likely than males to endorse other gender attraction and other-gender sexual experience. Among bisexuals, females were more likely than males to endorse other-gender sexual experience and use of a sexual minority identity. Among mostly heterosexuals, females were more likely than males to endorse same-gender attractions, same-gender sexual experience, and other-gender sexual experience. Finally, among heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, females were more likely than males to endorse same-gender attractions, other-gender sexual experience, and use of a sexual minority identity.

Table 2.

Endorsement and Age Reached Sexual Orientation Developmental Milestones by Gender for Female (N=1235) and Male (N=398) Young Adults, Ages 22 to 29 Years, in the Growing Up Today Study who Reported Any Same-Gender Orientation in 2010

| Endorsement of Milestones (%, n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Milestones | Females | Males | Females vs. Males (p-value) | Females vs. Males (Cramer’s v) |

| Same-gender Attraction | 80.8 (995) | 62.3 (246) | <.001 | 0.19 |

| Other-gender attraction | 97.9 (1201) | 85.8 (339) | <.001 | 0.24 |

| Same-gender sexual experience | 61.5 (759) | 64.9 (257) | 0.23 | 0.03 |

| Other-gender sexual experience | 99.2 (1182) | 84.4 (335) | <.001 | 0.31 |

| Sexual minority identity | 63.2 (777) | 60.4 (239) | 0.31 | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| Age Reached Milestones (age in years, M, SD) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Milestones | Females | Males | Females vs. Males (p-value) | Females vs. Males (Cohen’s d) |

|

| ||||

| Same-gender attraction | 16.8 (4.0) | 14.9 (5.0) | <.001 | 0.42 |

| Other-gender attraction | 9.8 (3.4) | 9.6 (3.4) | 0.24 | 0.06 |

| Same-gender sexual experience | 18.1 (4.2) | 15.2 (5.5) | <.001 | 0.59 |

| Other-gender sexual experience | 16.2 (2.7) | 16.6 (3.4) | 0.03 | −0.13 |

| Sexual minority identity | 17.5 (3.9) | 16.5 (4.3) | 0.001 | 0.24 |

Note. Timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones is measured by age in years. Age range for same-gender attraction: 3–27 years for females, 0–27 years for males. Age range for other gender attraction: 0–26 years for females, 1–24 years for males. Age range for same-gender sexual experience: 2–27 years for females, 3–26 years for males. Age range for other gender sexual experience: 1–28 years for females, 5–26 years for males. Age range for sexual minority identity: 0–28 years for females, 4–27 years for males. Reported p-values are from chi-square tests for endorsement and t-tests for timing.

Table 3.

Endorsement of Sexual Orientation Developmental Milestones by Gender and Sexual Orientation Group for Female (N=1235) and Male (N=398) Young Adults, Ages 22 to 29 Years, in the Growing Up Today Study who Reported Any Same-Gender Orientation in 2010

| Females (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Milestones | Lesbian (n = 84) | Bisexual (n = 127) | Mostly heterosexual (n = 776) | Hetero w/same-gender sexual experience (n = 248) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (p-values) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (Cramer’s v) |

| Same-gender attraction | 98 | 98 | 86 | 48 | <.001 | 0.43 |

| Other-gender attraction | 71 | 99 | 100 | 100 | <.001 | 0.50 |

| Same-gender sexual experience | 95 | 77 | 43 | 100 | <.001 | 0.51 |

| Other-gender sexual experience | 93 | 100 | 99 | 100 | <.001 | 0.19 |

| Sexual minority identity | 94 | 95 | 68 | 20 | <.001 | 0.49 |

|

| ||||||

| Males (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Milestones | Gay (n = 98) | Bisexual (n = 16) | Mostly heterosexual (n = 188) | Hetero w/same-gender sexual experience (n = 96) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (p-values) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (Cramer’s v) |

|

| ||||||

| Same-gender attraction | 100 | 100 | 64 | 15 | <.001 | 0.64 |

| Other-gender attraction | 43 | 100 | 100 | 99 | <.001 | 0.70 |

| Same-gender sexual experience | 95 | 63 | 31 | 100 | <.001 | 0.68 |

| Other-gender sexual experience | 51 | 88 | 95 | 97 | <.001 | 0.53 |

| Sexual minority identity | 92 | 69 | 69 | 10 | <.001 | 0.61 |

|

| ||||||

| Females vs. Males (p-values) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Milestones | Lesbian/gay | Bisexual | Mostly heterosexual | Hetero w/same-gender sexual experience | ||

|

| ||||||

| Same-gender attraction | .21 | 1.00 | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Other-gender attraction | <.001 | 1.00 | - | .48 | ||

| Same-gender sexual experience | 1.00 | .22 | .003 | - | ||

| Other-gender sexual experience | <.001 | .01 | <.001 | .02 | ||

| Sexual minority identity | .57 | .003 | .89 | .04 | ||

Note. The sexual minority identity milestone refers to lifetime sexual minority identification reported prior to sexual orientation endorsed in 2010. Sexual orientation in 2010 was used to create the sexual orientation subgroups. Reported p-values are from chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests. No p-value is reported for gender differences in endorsement of sexual experience by heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience because both groups reported 100% endorsement. 100% endorsement of sexual experience reported for heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience was by design. Also, p-value for gender differences in other-gender attraction among mostly heterosexuals was not reported because all participants reported other-gender attraction.

Females

Milestone endorsement was compared between sexual orientation groups among females (Table 3). Bisexuals and lesbians endorsed same-gender attractions and a sexual minority identity more frequently than other sexual orientation groups, whereas heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience endorsed these milestones less frequently. Other-gender attraction was endorsed less frequently by lesbians than by the other three sexual orientation groups, but there was high endorsement of lifetime other-gender sexual experience by all four groups. By definition, 100% of heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience endorsed same-gender sexual experience; a high percentage of lesbians also endorsed same-gender sexual experience.

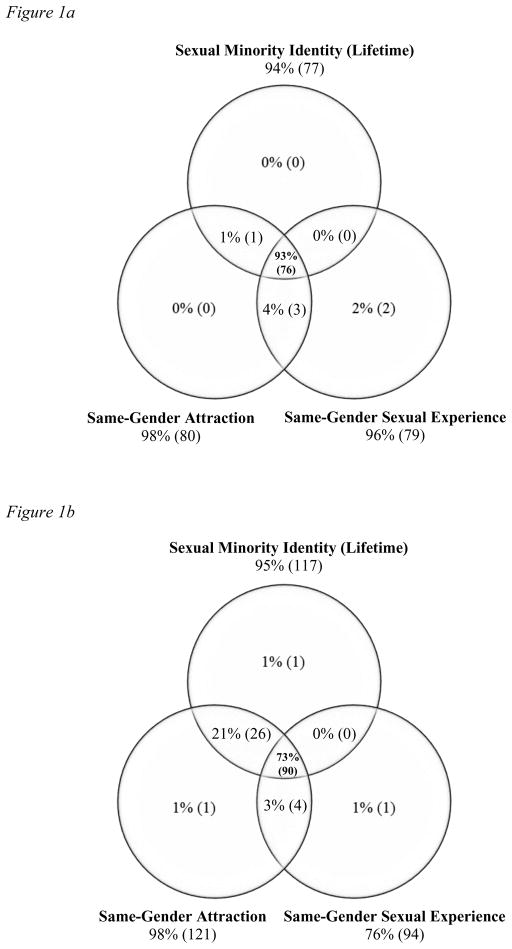

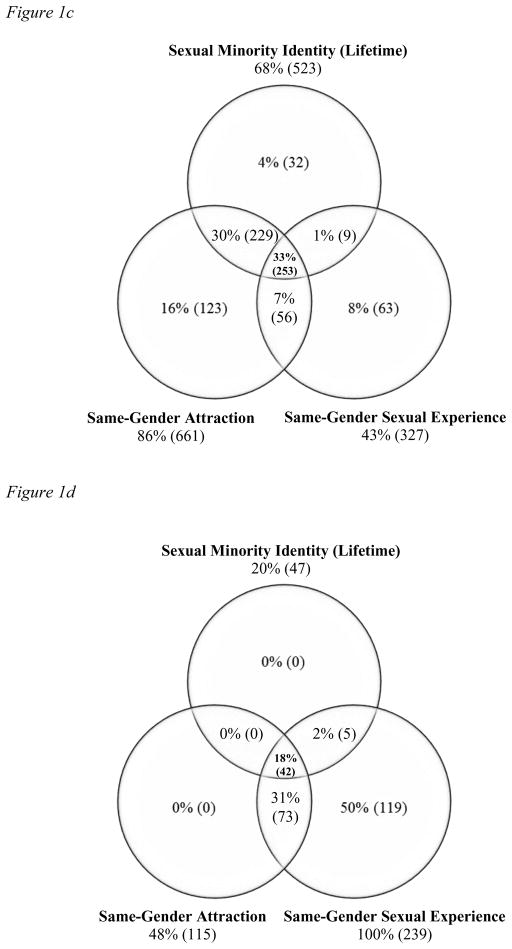

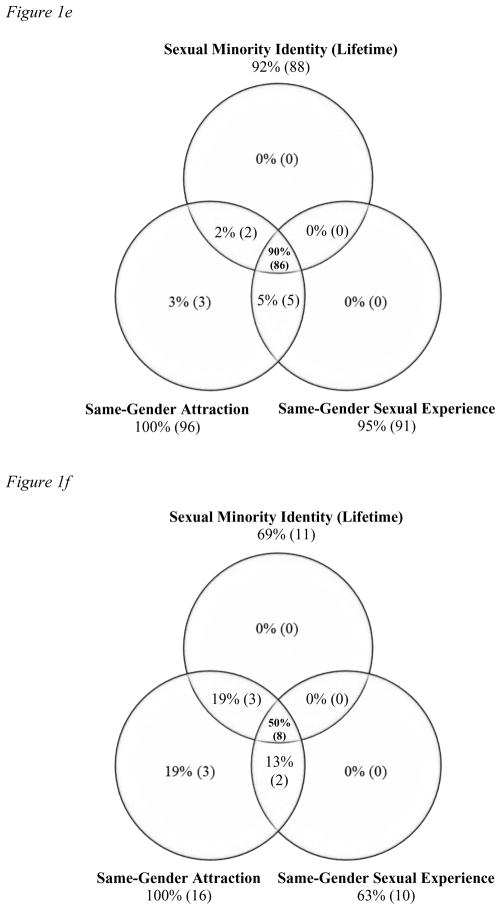

The pattern of sexual minority milestone endorsement within sexual orientation groups was also examined among females who provided a response to all three sexual minority milestone items (same-gender attraction, same-gender sexual experience and sexual minority identification) (Figure 1a–d). It was more typical for bisexuals and lesbians to endorse all three sexual minority milestones (73% and 93%, respectively) than to endorse only one sexual minority milestone (1% and 2%, respectively, endorsed same-gender sexual experience only). Heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience showed a different pattern: only 18% endorsed all three sexual minority milestones, but 50% endorsed only same-gender sexual experience (Figure 1d).

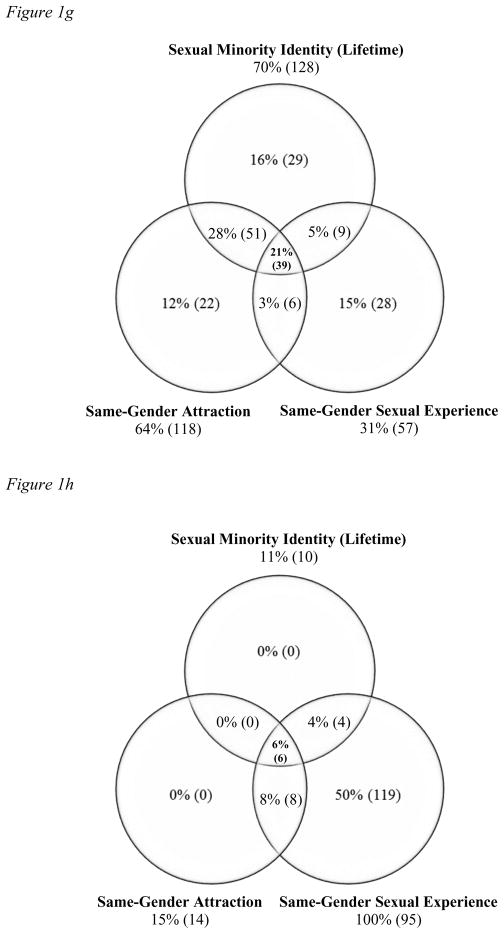

Figure 1.

Endorsement of sexual minority developmental milestones ever in lifetime prior to 2010 by gender and sexual orientation group (based on current sexual orientation in 2010). Sample sizes for each sexual orientation group reflect the number of participants who provided a response for all three items assessing endorsement of milestones. Numbers outside the Venn diagram represent the total proportion of participants who ever endorsed the milestone in their lifetime regardless of ever endorsing the other two milestones. Numbers inside the Venn diagram represent the proportion of participants who ever endorsed each milestone in their lifetime alone and in combination with the other two milestones. For example, among heterosexual females with same-gender sexual experience, 20% endorsed a sexual minority identity overall, 0% endorsed a sexual minority identity without endorsing the other two milestones, 2% endorsed a sexual minority identity and same-gender sexual experience without endorsing same-gender attraction, and 18% endorsed all three milestones. 100% endorsement of same-gender sexual experience by heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience is by design.

Figure 1a. Females reporting a lesbian orientation in 2010 (n=82)

Figure 1b. Females reporting a bisexual orientation in 2010 (n=123)

Figure 1c. Females reporting a mostly heterosexual orientation in 2010 (n=765)

Figure 1d. Females reporting a heterosexual orientation in 2010 with lifetime same-gender sexual experience (n=239)

Figure 1e. Males reporting a gay orientation in 2010 (n=96)

Figure 1f. Males reporting a bisexual orientation in 2010 (n=16)

Figure 1g. Males reporting a mostly heterosexual orientation in 2010 (n=184)

Figure 1h. Males reporting a heterosexual orientation in 2010 with lifetime same-gender sexual experience (n=95)

Males

Milestone endorsement was compared between sexual orientation groups among males (Table 3). Bisexuals and gay males endorsed same-gender attractions and gay males endorsed a sexual minority identity more frequently than other sexual orientation groups, whereas heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience endorsed these milestones less frequently. Gay males had the lowest frequency of endorsing other-gender attraction and other-gender sexual experience, compared to the other three sexual orientation groups. By definition, 100% of heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience endorsed same-gender sexual experience; a high percentage of gay males also endorsed same-gender sexual experience.

The pattern of sexual minority milestone endorsement within sexual orientation groups was also examined among males who provided a response to all three sexual minority milestone items (Figure 1e–h). The males followed a pattern similar to females with respect to endorsement of the three milestones.

Timing of Sexual Orientation Developmental Milestones

Females and males

Mean age at achieving each milestone was compared between females and males without regard to sexual orientation subgroups (Table 2) and within each sexual orientation group (Table 4). Males reached all three sexual minority milestones earlier than females (Table 2); this was also true among lesbians and gay males (Table 4). However, females reached the other-gender sexual experience milestone earlier than males. Among mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, males reached the other-gender attraction milestone earlier than females. Among heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, males also reached the sexual minority identity milestone earlier than females. No significant gender differences were found for milestone timing among bisexuals.

Table 4.

Age Reached Sexual Orientation Developmental Milestones by Gender and Sexual Orientation Group for Female (N=1235) and Male (N=398) Young Adults, Ages 22 to 29 Years, in the Growing Up Today Study who Reported Any Same-Gender Orientation in 2010

| Females (age in years, M, SD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Milestones | Lesbian (n = 84) | Bisexual (n = 127) | Mostly heterosexual (n = 776) | Hetero w/same-gender sexual experience (n = 248) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (p-values) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (Cohen’s d) |

| Same-gender attraction | 14.8 (4.4) | 14.5 (4.3) | 17.3 (3.8) | 17.3 (3.1) | <.001 | 0.08 |

| Other-gender attraction | 12.6 (3.9) | 10.5 (3.4) | 9.6 (3.2) | 9.3 (3.2) | <.001 | 0.04 |

| Same-gender sexual experience | 18.3 (3.5) | 17.9 (4.0) | 18.0 (4.3) | 18.1 (4.4) | 0.91 | <.001 |

| Other-gender sexual experience | 15.5 (3.7) | 15.9 (2.9) | 16.5 (2.6) | 15.6 (2.5) | <.001 | 0.02 |

| Sexual minority identity | 17.6 (3.7) | 16.9 (4.0) | 17.7 (3.9) | 16.4 (4.3) | 0.05 | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| Males (age in years, M, SD) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Milestones | Gay (n = 88) | Bisexual (n = 16) | Mostly heterosexual (n = 188) | Hetero w/same-gender sex exper (n = 96) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (p-values) | Sexual Orientation Comparison (Cohen’s d) |

|

| ||||||

| Same-gender attraction | 11.9 (3.6) | 16.4 (4.3) | 17.3 (4.7) | 14.8 (5.4) | <.001 | 0.26 |

| Other-gender attraction | 11.7 (4.3) | 10.7 (3.4) | 9.7 (3.2) | 8.2 (2.8) | <.001 | 0.10 |

| Same-gender sexual experience | 16.9 (3.7) | 18.7 (3.9) | 16.3 (5.8) | 12.4 (5.7) | <.001 | 0.16 |

| Other-gender sexual experience | 17.4 (3.2) | 17.1 (2.2) | 16.8 (3.0) | 15.8 (4.2) | 0.035 | 0.03 |

| Sexual minority identity | 15.0 (3.9) | 15.9 (2.8) | 17.9 (4.0) | 13.0 (5.3) | <.001 | 0.13 |

|

| ||||||

| Females vs. Males (p-values) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Milestones | Lesbian/gay | Bisexual | Mostly heterosexual | Hetero w/same-gender sex exper | ||

|

| ||||||

| Same-gender attraction | <.001 | .10 | .91 | .11 | ||

| Other-gender attraction | .25 | .87 | .78 | .003 | ||

| Same-gender sexual experience | .01 | .54 | .03 | <.001 | ||

| Other-gender sexual experience | .01 | .16 | .17 | .74 | ||

| Sexual minority identity | <.001 | .40 | .68 | .04 | ||

Note. The sexual minority identity milestone refers to lifetime sexual minority identification reported prior to sexual orientation endorsed in 2010. Sexual orientation in 2010 was used to create the sexual orientation subgroups. Reported p-values are from ANOVAs for timing.

Females

Among females, the mean age at which each milestone was reached was compared between sexual orientation groups (Table 4). Significant sexual orientation group differences were found for timing of same-gender attraction, other-gender attraction, and other-gender sexual experience. Lesbians and bisexuals reached the same-gender attraction milestone earliest at ages 14.5 years and 14.8 years, respectively. Mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience reached the other-gender attraction milestone earliest at ages 9.6 years and 9.3 years, respectively. Lesbians and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience reached the other-gender sexual experience milestone earliest at ages 15.5 years and 15.6 years, respectively. The mean age of attainment was significantly different for the three sexual minority milestones, p < .001.

Across females, average milestone ages occurred in the following order: other-gender attraction at age 9.8 years, other-gender sexual experience at age 16.2 years (6.4 years later than other-gender attraction), same-gender attraction at age 16.8 years (0.6 years later than other-gender sexual experience), sexual minority identification at age 17.5 years (0.7 years later than same-gender attraction), and same-gender sexual experience at age 18.1 years (0.6 years later than sexual minority identification; Table 2). For sexual minority sub-groups, average milestone ages occurred in the same order for lesbians and bisexuals: other-gender attractions, same-gender attraction, other-gender sexual experience, sexual minority identification, same-gender sexual experience (Table 4). Average milestone ages occurred in a similar order for mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, with both groups experiencing other-gender attraction first and other-gender sexual experience second. However, mostly heterosexuals then experienced same-gender attraction before sexual minority identification, whereas heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience experienced sexual minority identification before same-gender attraction. Both groups experienced same-gender sexual experience as the last milestone.

Males

Among males, the mean age at which each milestone was reached was compared between sexual orientation groups (Table 4). Significant sexual orientation group differences were found for timing of all five milestones. Gay males reached the same-gender attraction milestone earliest at age 11.9 years, and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience reached the other four milestones earliest at age 8.2 years for other-gender attraction, age 12.4 years for same-gender sexual experience, age 13 for sexual minority identification, and age 15.8 years for other-gender sexual experience.

Across males, average milestone ages occurred in the following order: other-gender attraction at age 9.6 years, same-gender attraction at age 14.9 years (5.3 years later than other-gender attraction), same-gender sexual experience at age 15.2 years (0.3 years later than same-gender attraction), sexual minority identification at age 16.5 years (1.3 years later than same-gender sexual experience), and other-gender sexual experience at age 16.6 years (0.1 years later than sexual minority identification; Table 2). However, average milestone ages occurred in a different order for each of the sexual orientation subgroups (Table 4). All groups experienced other-gender attraction first, but then experienced the other milestones in different orders. Mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience both experienced same-gender sexual experience as the second milestone, whereas gay males experienced same-gender attraction and bisexuals experienced sexual minority identification as the second milestone. Gay males and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience experienced other-gender sexual experience as the last milestone, whereas bisexuals experienced same-gender sexual experience as the last milestone and mostly heterosexuals experienced sexual minority identification as the last milestone.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe patterns of endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones across gender and sexual orientation groups using data from a national prospective cohort of youth who were not recruited based on sexual orientation. Much of previous research on sexual orientation developmental milestones has focused on lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals (D’Augelli, 2006; Floyd & Bakeman, 2006), without considering sexual orientation group differences beyond gender and whether milestones are relevant to the experiences of other sexual minority groups, such as mostly heterosexual. Results from this research suggest unique patterns of endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones across gender and sexual orientation groups.

Endorsement of Sexual Orientation Developmental Milestones

One goal of this study was to examine milestone endorsement within gender and sexual orientation groups. It is a common misperception that all sexual minorities progress through the same sexual orientation developmental milestones. Although some research has begun to show greater variability in the timing of when milestones are reached (Charbonneau & Lander, 1991; Diamond, 1998; Diamond & Savin-Williams, 2000; Floyd & Stein, 2002; Kitzinger & Wilkinson, 1995; Author et al., 1996; 2008; Worthington & Reynolds, 2009), much of this research is based on the assumption that each of these groups will reach such milestones at some point during sexual orientation development. Results from the current study suggest that sexual orientation developmental milestones may not be equally relevant for all gender and sexual orientation groups. However, it is possible that individuals who did not endorse milestones at the time of data collection may endorse such milestones later in life. Research on retrospective recall of sexual orientation developmental milestones in a large age-diverse sample found that milestones can indeed be reached at later ages (Author et al., 2011). However, the number of individuals who experience milestones later is likely to be small, as most experience milestones during adolescence.

Patterns of milestone endorsement differed across sexual orientation subgroups. Heterosexual females and males with same-gender sexual experience were the least likely to endorse same-gender attraction and ever use a sexual minority identity, compared to other sexual minority groups of the same gender. These findings suggest that same-gender attractions and the use of a sexual minority identity may be more relevant to the experiences of bisexual, lesbian, and gay individuals who were more likely to endorse these milestones. However, many heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience still endorsed same-gender attractions and lifetime sexual minority identification, suggesting that these milestones are also relevant for this group, even if these individuals did not currently endorse a sexual minority orientation in 2010.

The endorsement of same-gender attractions and sexual minority identification among heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience may represent a form of experimentation, rather than an indication of a sexual minority orientation. Same-gender sexual play is common during childhood (Martinson, 1994) and experimentation and exploration are considered integral to the process of general identity formation during adolescence (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1987) and into young adulthood. As evidence, some research has indicated that same-gender kissing is common among heterosexually identified women at college, who attribute this behavior in part to the belief that college is a time of experimentation (Yost & McCarthy, 2012). Models of sexual orientation development that are both specific to heterosexual identity development (e.g., Worthington et al., 2002) and encompass identity development for both sexual minorities and heterosexuals (Dillon, Worthington, & Moradi, 2011) include the component of active exploration as part of the process of forming a sexual orientation identity. Active exploration may include both same- and other-gender sexual behavior and cognitive exploration, such as “trying on” sexual orientation identity labels (Dillon et al., 2011). However, it is unclear whether same-gender sexual behavior among heterosexuals or other-gender sexual behavior among sexual minorities constitutes experimentation, sexual fluidity in sexual orientation (Diamond, 2008; Author, 2014), or other phenomena, such as nonconsensual sexual encounters. Research using longitudinal designs and mixed methods is needed to fully examine patterns of sexual fluidity in sexual orientation over time, as well as how individuals interpret and explain these changes.

It may be assumed that experiencing all three sexual minority developmental milestones (same-gender attractions, same-gender sexual experience, and sexual minority identification) will occur prior to having a sexual minority identity. However, not all sexual minorities experience all three milestones. Among heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, gender differences in milestone endorsement were found, with females more likely than males to endorse both same-gender attractions and lifetime sexual minority identification. One interpretation of these results is that it is not necessary to experience all three sexual minority milestones before adopting a current sexual minority identity. For some individuals, experiencing all three sexual minority developmental milestones may be necessary for current endorsement of sexual minority orientation, whereas for other individuals it may only be necessary to experience one or two milestones. Therefore, it is possible for individuals in this study to currently endorse a sexual minority orientation without having ever endorsed the sexual minority identity milestone; for example, 31% of females who responded mostly heterosexual and 6% of females who responded lesbian for their current sexual orientation never endorsed a sexual minority identity previously (Figures 1c and 1a, respectively).

Patterns of overlap in sexual minority milestone endorsement suggest that bisexuals, lesbians, and gay males were the most likely sexual orientation groups to have experienced all three milestones (see Figure 1a–h). Original conceptualizations of sexual minority development were formulated based on the experiences of lesbians and gay males (e.g., Cass, 1979). Therefore, it follows that these milestones would best capture the experiences of these sexual orientation groups. Results from this research suggest that these milestones are also relevant for bisexuals, especially bisexual females. For instance, 73% of bisexual females and 50% of bisexual males endorsed all three sexual minority milestones (Figure 1b and 1f, respectively). However, 21% of bisexual females and 19% of bisexual males endorsed only same-gender attraction and sexual minority identification, suggesting that many individuals who identify as bisexual have not acted on their same-gender attractions. It appears that for some bisexual individuals, having same-gender attractions is enough to qualify as bisexual, without having same-gender sexual experiences. More research is needed to understand how bisexually-identified individuals understand bisexuality.

Timing of Sexual Orientation Minority Developmental Milestones

Another goal of this study was to examine milestone timing by gender and sexual orientation subgroup. Consistent with previous research on gender differences in milestone timing (D’Augelli, 2006; Floyd & Bakeman, 2006; Author, 2014; Author et al., 1996), males in the current study reached most milestones earlier than females. Gender differences in milestone timing were also found within some sexual orientation groups. Among lesbian and gay individuals, gender differences in timing were found for all milestones except other-gender attraction, with males reaching milestones earlier than females. Among mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, males experienced same-gender sexual experience earlier than females, and among heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, males used a sexual minority identity at a younger age than females. It is noteworthy than no significant gender differences in timing of milestones were found among bisexuals, although there were mean differences in the ages at which some milestones were reached. Considering that the current sample of bisexual males was quite small, more research is warranted to clarify whether gender differences in milestone timing exist among bisexuals.

Previous research on milestone timing has not examined specific sexual orientation groups independently from other sexual orientation groups (D’Augelli, 2006; Floyd & Bakeman, 2006; Author, 2014; Author et al., 1996). For females and males in the current study, sexual orientation group differences were found regarding milestone timing among those individuals who endorsed the milestones. Among females, sexual orientation group differences were found for same-gender attractions, other-gender attractions, and other-gender sexual experience, with lesbians and bisexuals reaching the same-gender attraction milestone at an earlier age than the other two groups, and mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience reaching the other-gender attraction milestone at an earlier age than the other two groups. Among males, sexual orientation group differences were found for all five milestones. Gay males experienced same-gender attraction earlier than other sexual minority groups, but heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience reached the other four milestones earlier than other sexual minority groups.

It was surprising that heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience were the youngest group to first use a sexual minority identity, considering that these individuals did not endorse a sexual minority orientation in 2010, when they were classified as “heterosexual with same-gender sexual experience.” It is possible that many of these individuals may have previously identified as a sexual minority and then relinquished that identity in favor of a heterosexual identity. However, a closer examination revealed that out of 96 heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience, only 16% identified themselves as a sexual minority in previous waves of data collection. Alternatively, it is possible that heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience initially identified as a sexual minority based on experiencing nonconsensual same-gender sex, but later realized they did not have a sexual minority orientation. Previous research using data from GUTS has indicated that nearly 35% of heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience report any sexual abuse, a percentage higher than all other sexual orientation groups (Roberts, Rosario, Corliss, Koenen, & Austin, 2012). It is clear that more research is needed to understand sexual orientation development among heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience.

The order in which milestones were reached was also examined by looking at the order of average milestone ages across the sample and within females and males. When sexual orientation groups were combined, both females and males experienced same-gender attraction at a younger age than the age at which the other two sexual minority milestones were experienced. On average, females appeared to follow an “identity-centered sequence” (Dubé, 2000) for sexual minority milestones, using a sexual minority identity before experiencing same-gender sexual experience, whereas males appeared to follow a “sex-centered sequence” (Dubé, 2000), experiencing same-gender sexual experience prior to using a sexual minority identity. However, taking into account other-gender milestones and examining sexual orientation sub-group differences painted a more complex picture of heterogeneity across sexual orientation groups. For instance, both females and males across all sexual orientation subgroups experienced other-gender attractions as the first milestone. All sexual minority female subgroups experienced same-gender sexual experience as the last milestone, but among males, gay males and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience experienced the other-gender sexual experience as the last milestone, whereas the last milestone for bisexuals was same-gender sexual experience and the last milestone for mostly heterosexuals was sexual minority identification. Future research could explore the order of milestones within individuals (rather than averaging across individuals) to get a better sense of individual developmental trajectories of sexual minority development.

Gender differences in milestone order may be related to societal norms regarding gender and sexuality. For instance, adolescent girls are expected to be sexually passive and are socialized to believe that they are bad if they have desire and sexual agency (Tolman, 2002). Conversely, adolescent boys are expected to be sexually aggressive and agentic. Societal norms regarding gender and sexuality may result in females engaging in same-gender sexual behavior at an older age than males (age 18.1 years vs. 15.2 years, respectively) because they may be less likely to act on feelings of desire and attraction. However, results from the current study indicated that females engaged in other-gender sexual behavior at a slightly younger age than males (age 16.2 years vs. 16.6 years, respectively), which is inconsistent with societal norms regarding gender and sexuality.

Gender differences in milestone order may also be related to how the same-gender sexual experience milestone question was interpreted by female participants. The wording of this question was “During your lifetime, have you ever had sexual contact [italics added] with a female.” There is much heterogeneity in how “sex” between two females is defined (Horowitz & Spicer, 2013). It is possible that sexual minority females are just as likely as sexual minority males to have experienced some form of sexual contact (e.g., kissing, touching genitalia), but that only some sexual minority females interpreted or reported their experiences as sexual contact. Further exploration of how sexual minority females and males understand same-gender sexual contact in relation to their sexual orientation identity is warranted.

Sexual orientation group differences in milestone order were also found within females and males. Among both females and males, a substantial amount of variability was seen among sexual orientation subgroups in that each group reached milestones in a different order. These findings support a developmental trajectories approach that allows for heterogeneity at the sexual orientation subgroup level (Floyd & Stein, 2002; Author et al., 2008; Worthington & Reynolds, 2009). On average, mostly heterosexuals and heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience followed a sex-centered milestone sequence, experiencing same-gender sexual experience prior to experiencing other milestones. Dubé’s (2000) research found that sexual minority men who followed this milestone sequence reported higher levels of homophobia toward other males, which may help to explain why heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience in the current study did not report a sexual minority orientation when they were surveyed in 2010. However, a lack of sexual minority identification among heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience may also be explained by experiencing nonconsensual same-gender sexual contact.

Implications for Sexual Minority Health

The endorsement of milestones may have implications for the health and well-being of sexual minorities. The Minority Stress Model proposes that experiencing prejudice and discrimination based on sexual minority status leads to negative mental and physical health outcomes (Meyer, 2003). In particular, Meyer proposed that sexual minority identification may be linked to a number of stress processes, including the internalization of sexual minority stigma. This may have implications for individuals who have same-gender attractions and engage in same-gender sexual experiences, but do not identify as a sexual minority (e.g., heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience). It is possible that these individuals are more protected from sexual minority stigma. This would be an interesting area of future research.

The timing of milestones may also have important implications for the health and well-being of sexual minorities (Author et al., 2013). The Minority Stress Model may be used to understand the association between earlier age of sexual minority developmental milestones and adverse health outcomes. Some research has suggested that sexual minorities who reach sexual minority milestones in early to mid-adolescence may be at greater risk for adverse mental and physical health outcomes than sexual minorities who reach sexual minority milestones in late adolescence or young adulthood. For instance, earlier age of sexual minority developmental milestones was positively linked to childhood maltreatment among sexual minority females (Corliss, Cochran, Mays, Greenland, & Seeman, 2009) and sexual minority-related victimization and depression among sexual minority males (Friedman, Marshal, Stall, Cheong, & Wright, 2008). Other research has documented that sexual minorities are more likely than heterosexuals to experience victimization (Author et al., 2012). It is possible that individuals who reach sexual minority milestones earlier may have worse outcomes than individuals who reach sexual minority milestones at an older age, in part because they may reach milestones at a point in development (e.g., early adolescence) in which they may not have the skills needed to cope effectively with minority stress (Author et al., 2013). More research is needed to understand the link between timing of milestones and minority stress among sexual minorities.

Limitations

Some limitations of this research should be mentioned. Although GUTS offers numerous benefits associated with being a national prospective cohort, the sample is largely homogenous in terms of race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, due to the fact that all of the participants were children of professional nurses. Some previous research has suggested that the timing of sexual minority development may differ across race/ethnicity groups (Dubé & Savin-Williams, 1999; Parks et al., 2004), although other research has found no race/ethnicity differences (Author et al., 2004) and such differences are likely to be culturally and historically bound. Future research should assess milestones in samples that represent a greater range of race/ethnicities. Another potential limitation of this study is that some sexual orientation groups had a small sample size (e.g., bisexual males), which limits the stability of estimates. However, GUTS is useful for studying sexual minorities from a population-based approach because participants were not recruited based on their sexual minority status.

In terms of measurement, the primary sexual orientation question in GUTS is limited in combining attractions and sexual orientation identity; although previous research has demonstrated that this assessment of sexual orientation may be most consistently understood by adolescents (Author et al., 2007). The sexual orientation question used in this study is also limited in that it does not include newer sexual orientation identity labels, such as queer or pansexual. In addition, the definition provided for bisexuality as equal attraction to both males and females may not represent the experiences of individuals who identify as bisexual, but have attraction to more than one gender that is not of equal proportion. The discrepancy between the wording of the sexual orientation question (“Which of the following best describes your feelings?”) and the sexual minority identity milestone question (“During your life, have you ever identified yourself as ‘mostly heterosexual,’ bisexual, or lesbian or gay?”) may have lead some participants to currently endorse a sexual orientation (e.g., describing feelings as “completely homosexual (gay/lesbian, attracted to persons of the same sex)”), but not endorse having identified as such (e.g., using the label “lesbian”) in the past. Additionally, the wording “during your life,” may have led some participants to respond regarding their sexual minority identity to include both current and past sexual minority identification. However, age of first sexual minority identification was also assessed, which allowed us to determine when participants first adopted a sexual minority identity, and thus to distinguish between past and current identification.

Finally, some participants reported reaching milestones at very young ages (e.g., age 0 or 1 year old). It is unlikely that participants had the cognitive awareness at that developmental stage to recognize attractions or identity, or to accurately remember such feelings or experiences. However, it is possible that participants responded as such to indicate that they have always felt these attractions or identified as a sexual minority. It should also be noted that we do not have information regarding whether first same-gender sexual experiences were consensual, although we do know the percentage of individuals within each sexual orientation group reporting sexual abuse (Roberts et al., 2012). The results for heterosexual males with same-gender sexual experience in particular should be interpreted in light of this limitation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a number of gender and sexual orientation group differences were found in endorsement and timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones. Based on these results, it appears that the three sexual minority milestones assessed in this study may be most relevant to the experiences of lesbians, gay males, and bisexual females and males, although these milestones may also be relevant for mostly heterosexuals and heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience. The inclusion of other-gender milestones allows for a more complete picture of sexual orientation development across all sexual minority groups. In addition, variability across gender and sexual orientation groups in timing and sequence of average age of milestones was common. Findings from this study shed light on the relevance of milestones for understanding sexual orientation development of sexual minorities and support previous research advocating for sensitivity to group-level heterogeneity in trajectories for understanding sexual minority development. More research is needed to better understand sexual orientation development among mostly heterosexuals and especially heterosexuals with same-gender sexual experience, whose patterns of milestone endorsement and timing differed substantially from those of other groups.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Katz-Wise, Scherer and Austin were supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NIH R01 HD066963) and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration (Leadership Education in Adolescent Health project 6T71-MC00009). Drs. Rosario and Austin were supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NIH R01 HD057368). Dr. Austin was also supported by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration (T76-MC00001). Dr. Calzo was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH K01DA034753).

Contributor Information

Sabra L. Katz-Wise, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital and Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Margaret Rosario, Department of Psychology, City University of New York–City College and Graduate Center.

Jerel P. Calzo, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital and Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Emily A. Scherer, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA

Vishnudas Sarda, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

S. Bryn Austin, Division of Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard School of Public Health, and Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

- Author et al. (2007).

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School. Nurses’ Health Study. Retrieved from http://www.channing.harvard.edu/nhs/

- Author et al. (2011).

- Cass VC. Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau C, Lander PS. Redefining sexuality: Women becoming lesbian in midlife. In: Sang B, Warshow J, Smith AJ, editors. Lesbians at midlife: The creative transition. San Francisco, CA: Spinsters; 1991. pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Mays VM. Physical health complaints among lesbians, gay men, and bisexual and homosexually experienced heterosexual individuals: Results from the California Quality of Life Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2048–2055. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Greenland S, Seeman TE. Age of minority sexual orientation development and risk of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts in women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:511–521. doi: 10.1037/a0017163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Developmental and contextual factors and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. Development of sexual orientation among adolescent and young adult women. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1085–1095. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. Was it a phase? Young women’s relinquishment of lesbian/bisexual identities over a 5-year period. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:352–364. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Savin-Williams RC. Explaining diversity in the development of same-sex sexuality among young women. Journal of Social Issues. 2000;56:297–313. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Worthington RL, Moradi B. Sexual identity as a universal process. In: Schwartz SJ, Luyskx K, Vignoles VL, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 649–670. [Google Scholar]

- Dubé EM. The role of sexual behavior in the identification process of gay and bisexual males. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:123–132. doi: 10.1080/00224490009552029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubé EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual minority male youths. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1389–1398. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.35.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Frazier AL, Gillman MW, Colditz GA. Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:754–760. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Bakeman R. Coming-out across the life course: Implications of age and historical context. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Stein TS. Sexual orientation identity formation among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Multiple patterns of milestone experiences. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:167–191. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Cheong J, Wright ER. Gay-related development, early abuse and adult health outcomes among gay males. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:891–902. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnets LD, Kimmel DC. Lesbian and gay male dimensions in the psychological study of human diversity. In: Garnets LD, Kimmel DC, editors. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay male experience. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1993. pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL. The life course development of human sexual orientation: An integrative paradigm. Human Development. 2005;48:267–290. doi: 10.1159/000086872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks GR, Lee TT. Public attitudes toward gays and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality. 2006;51:57–77. doi: 10.1300/J082v51n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz AD, Spicer L. “Having sex” as a graded and hierarchical construct: A comparison of sexual definitions among heterosexual and lesbian emerging adults in the U.K. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50:139–150. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.635322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author. (2014).

- Author et al. (2012).

- Kitzinger C, Wilkinson S. Transitions from heterosexuality to lesbianism: The discursive production of lesbian identities. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:95–104. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.31.1.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klein F. The bisexual option. 2. New York, NY: Haworth Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Klein F, Sepekoff B, Wolf TJ. Sexual orientation: A multi-variable dynamic process. Journal of Homosexuality. 1985;11:35–49. doi: 10.1300/J082v11n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Identity in adolescence. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. pp. 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Martinson FM. The sexual life of children. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S, Schwitzer AM. Stages of identity development among college students with minority sexual orientations. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 1999;13:41–65. doi: 10.1300/J035v13n04_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Bahlburg H, Ehrhardt A, Exner T, Gruen R. Sexual Risk Behavior Assessment Schedule-Youth. New York, NY: Columbia University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EM, Steiner MG, Thompson EM. Processes of sexual orientation questioning among heterosexual men. Men and Masculinities. 2010;12:425–443. doi: 10.1177/1097184X08322630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EM, Thompson EM. Processes of sexual orientation questioning among heterosexual women. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48:16–28. doi: 10.1080/00224490903370594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks CA, Hughes TL, Matthews AK. Race/ethnicity and sexual orientation: Intersecting identities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:241–254. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AL, Rosario M, Corliss HL, Koenen KC, Austin SB. Elevated risk of posttraumatic stress in sexual minority youths: Mediation by childhood abuse and gender nonconformity. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1587–1593. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Author et al. (1996).

- Author et al. (2013).

- Author et al. (2014).

- Author et al. (2004).

- Author et al. (2008).

- Author et al. (2012).

- Author et al. (2009).

- Savin-Williams RC, Vrangalova Z. Mostly heterosexual as a distinct sexual orientation group: A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Developmental Review. 2013;33:58–88. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2013.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW, Rosario M, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Scharf-Matlick AA. Test-retest reliability of self-reported sexual behavior, sexual orientation, and psychosexual milestones among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35:225–234. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-9006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E, Morgan EM. “Mostly straight” young women: Variations in sexual behavior and identity development. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:15–21. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL. Dilemmas of desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington RL, Reynolds AL. Within-group differences in sexual orientation and identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:44–55. doi: 10.1037/a0013498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington RL, Savoy HB, Dillon FR, Vernaglia ER. Heterosexual identity development: A multidimensional model of individual and social identity. The Counseling Psychologist. 2002;30:496–531. doi: 10.1177/00100002030004002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yost MR, McCarthy L. Girls gone wild? Heterosexual women’s same-sex encounters at college parties. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2012;36:7–24. doi: 10.1177/036168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]