Abstract

Vitamin D is a potent immunomodulator capable of dampening inflammatory signals in several cell types involved in the asthmatic response. Its deficiency has been associated with increased inflammation, exacerbations and overall worse outcomes in patients with asthma. Given the increase in the prevalence of asthma over the last few decades, there has been enormous interest in the use of vitamin D supplementation as a potential therapeutic option. Several studies have found that low serum levels of vitamin D (< 20 ng/ml) are associated with increased exacerbations, increased airway inflammation, decreased lung function and poor prognosis in asthmatic patients. Results from the in vitro and in vivo studies in animals and human have suggested that supplementation with vitamin D can ameliorate several hallmark features of asthma. However, the findings obtained from clinical trials are controversial and do not unequivocally support the beneficial role of vitamin D in asthma. Largely, interventional studies in children, pregnant women and adults have primarily found little-to-no effect of vitamin D supplementation on improved asthma symptoms, onset or progression of the disease. This could be related to the severity of the disease process and other confounding factors. Despite the conflicting data obtained from clinical trials, vitamin D deficiency does influence the inflammatory response in the airways. Further studies are needed to determine the exact mechanisms by which vitamin D supplementation may induce anti-inflammatory effects. Here, we critically reviewed the most recent findings from in vitro studies, animal models, and clinical trials regarding the role of vitamin D in bronchial asthma.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Asthma, Immunomodulation, Clinical trials

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic disorder of the conducting airways which is characterized by reversible airway obstruction, cellular infiltration and airway inflammation. The response involves the interplay of genetic and environmental factors as well as the activation of cells in the innate and adaptive immune systems.1 The disease is a major public health problem globally, affecting approximately 300 million people worldwide. Per the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the asthma epidemic is on the rise which creates an immense economic burden of approximately $54 billion USD annually from lost school and work days, medical costs and early deaths.2

Despite several advances in the field, there is currently no cure for asthma. Treatment options for managing symptoms of the disease include the use of corticosteroids (widely used to control asthma symptoms), with or without β2-adrenergic receptor agonists (short-acting receptor agonists that relieve bronchoconstriction and long-acting receptor agonists that offers extended control of contractions).1,3 Although these drugs have a wide range of anti-inflammatory properties, they do not prevent long term decline in lung function. Given the rise in asthma across the globe, better treatment options are needed to combat the disease.

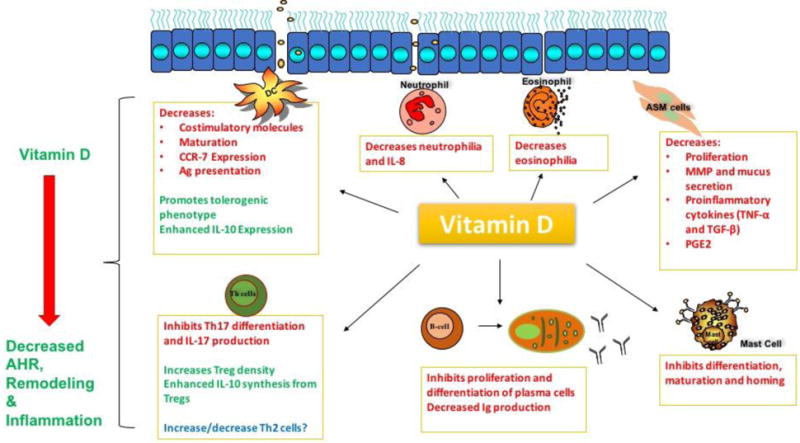

Over the last 20 years, vitamin D, through the activation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR), has been shown to have an immunomodulatory effect on a host of immune cells, including dendritic cells (DCs),4 macrophages, B and T lymphocytes5,6 as well as structural cells in the airways (Figure 1).1 Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to increase incidence of respiratory diseases like asthma with its supplementation shown to alleviate these effects in some cases (reviewed extensively in6–8). Results obtained from studies using animal models and human cells regarding the therapeutic effect of vitamin D supplementation has conflicted those obtained from some clinical trials. In this review, we critically reviewed the most recent findings regarding the role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis, prevention and treatment of bronchial asthma.

Figure 1. Immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D on inflammatory cells in allergic asthma.

Vitamin D, by binding and activating VDR, has been found to alleviate inflammation associated with allergic asthma. In ASM cells, vitamin D reduced proliferation, production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, MMP and mucus secretion. Vitamin D has been shown to decrease costimulatory molecules, CCR-7 expression, maturation and antigen presentation in DCs while promoting tolerogenic DCs with increased IL-expression. In T-lymphocytes, vitamin D has been reported to shift the balance from Th17 cells to Treg cells evidenced by decrease production of IL-17 and increased production of IL-10. The hormone inhibits differentiation and proliferation of B-cells to plasma cells and is believed to play a role in decreasing antibody production. In innate immune cells involved in asthma, vitamin D has been shown to inhibit differentiation, maturation, homing and cytokine secretion from mast cells, neutrophils and eosinophils. The overall effect of this immunomodulation is decreased airway hyper-responsive, inflammation and remodeling in asthma. AHR-airway hyper-responsiveness; Ag-antigen; IL-interleukin; Th-T helper cell; TNF-tumor necrosis factor; TGF-transforming growth factor; Treg-T regulatory cells; PGE2-prostaglandin E2

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a pre-prohomone that can be obtained from two major sources, skin exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) light as well as dietary intake from sources such as fish oils, fish, liver, egg yolk and dietary supplements.9,10 Vitamin D synthesis is initiated in the skin via the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) to previtamin D3 after exposure to UVB rays, and is then transformed to vitamin D3, also known as cholecalciferol, by a thermally induced isomerization. Vitamin D3 then enters the circulation and travels to the liver where it is hydroxylated to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], the circulating metabolite. To achieve stability in circulation, 25(OH)D must bind to the vitamin D binding protein (VDBP).6,10 A second hydroxylation occurs primarily in the kidney by the enzyme 1-α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) to produce 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3], more commonly known as calcitriol, the active metabolite. To exhibit its biological activity intracellularly, 1,25(OH)2D3 binds to the VDR in the cytoplasm. This complex heterodimerizes with retinoid X receptor (RXR) and is translocated to the nucleus where it can bind to vitamin D response elements (VDRE) leading to the activation or repression of transcription of target genes.1,6,9,10

Vitamin D and Asthma

Vitamin D status is best assessed by measuring serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D since it is the highest of all the metabolites and has a half-life of about 3 weeks. There is some controversy regarding the best method for assessing serum vitamin D levels in human subjects. The current gold standard technique being used in large medical labs is liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in isotype dilution. Other less specific methods such as radioimmunoassay, ELISA and chemiluminescence technologies are utilized by several laboratories.11,12 Vitamin D deficiency is defined as a serum concentration of less than 20 ng/ml (50 nmol/L) and its insufficiency as a serum concentration between 21–29 ng/ml (50–70 nmol/L).11–13 Epidemiological data suggest that the main factors that determine 25(OH)D serum levels are skin pigmentation (heavily pigmented skins have lower levels compared to lighter skins), sun exposure, age, gender, latitude of residence (higher latitudes have decreased opportunity for vitamin D skin synthesis), diet and vitamin D fortification.9 Although research has provided us with a much better understanding of vitamin D and its mechanisms, vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency are greatly increasing in the global population. Several studies have shown that despite fortification of certain foods and the intake of multivitamins, vitamin D deficiency is still prevalent in many developing countries even in sun-replete areas. This has been accredited to lifestyle changes including reduced exposure to the sunlight, shift from outdoor to indoor activities, the use of sunscreen as well as dietary changes.11,13 It appears that the fortification of foods in current doses are not adequate to prevent vitamin D deficiency. In addition, there are several other factors that could affect serum 25(OH)D levels. These include race, sex, binding proteins, single nucleotide polymorphisms in vitamin D binding proteins and vitamin D receptors, and other pharmacogenetics factors in vitamin D metabolism.

The role of vitamin D in asthma pathogenesis has been the focus of several research groups over the last two decades. Results from these studies have identified a link between vitamin D deficiency and an overall worse outcome of lung function and symptoms in patients with asthma.7,11 Several genetic studies have reported different gene polymorphisms of the VDR and VDBPs that have been linked to increased susceptibility of asthma.14 Epidemiological and meta-analysis studies suggest that low serum levels of vitamin D in children were associated with increased risks of asthma as well as increased symptoms, exacerbations and reduced lung function in children who already had asthma (reviewed in13). Low maternal vitamin D intake and levels during pregnancy has been linked to increased likelihood of wheezing in children.12,13 There is plenty of evidence to suggest that vitamin D acts on cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems as well as structural cells in the airways with its deficiency promoting inflammation and its supplementation alleviating these effects (Figure 1).1,4,5,7,9 However, results from clinical trials have been conflicting (Table 1) and there is still much debate as to whether or not vitamin D supplementation offers a viable alternative or adjunct therapy for asthmatic subjects.

Table 1.

Results from clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation in asthma

| Study Design | Parameters Measured | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VITAL is a 5-year U.S.-wide randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2 × 2 factorial trial | Study Ongoing | 63 | |

| Supplementation with vitamin D3 ([cholecalciferol], 2000 IU/day) and marine omega-3 FA 1g/day | |||

| Randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial conducted in 3 centers across the US | Parental report of physician-diagnosed asthma or recurrent wheezing through 3 years of age | Supplementation with 4000 IU increased vitamin D levels in women | 64 |

| 447 women received 4000 IU of vitamin D daily plus a prenatal vitamin containing 400 IU of vitamin D 436 women received placebo plus prenatal vitamin |

3rd trimester maternal 25(OH)D levels | Incidence of asthma and recurrent wheezing in children at age 3 was lower by 6%, however not significant | |

| Double-blind, single center, randomized clinical trial in Copenhagen Women received 2400 IU/day or placebo from 24 weeks of pregnancy to 1 week postpartum |

Age at onset of persistent wheeze in the first 3 years of life in Offspring Secondary outcomes: lung symptoms, asthma, respiratory tract infections, and neonatal airway immunology |

Supplementation with 2800 IU/d of vitamin D3 during the third trimester of pregnancy did not result in a statistically significant reduced risk of persistent wheeze in the offspring through age 3 years | 65 |

| AsthmaNet VIDA trial | Cold symptom severity | Vitamin D supplementation had no effect on primary outcome | 66 |

| 408 adult patients received placebo or cholecalciferol (100,000 IU load plus 4,000 IU/d) for 28 weeks as add-on therapy | |||

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | AHR to methacholine | Significant increases in vitamin D levels in treated group | 67 |

| Children aged 6–18 years with mild asthma received oral vitamin D (14,000 units) once weekly or placebo for 6 weeks | PC20 -FEV1 and FeNO IgE eosinophilia, cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-17, IFN-γ) |

There was no change in IgE, eosinophil count, cytokine levels, FeNO levels or PC20-FEV1 | |

| Randomized controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in London | Asthma exacerbation Secondary outcomes: Asthma control |

Supplementation had no effects on asthma exacerbations or secondary outcome parameters | 62 |

| 250 adults with asthma received six 2-monthly oral doses of 3 mg vitamin D3 or placebo over 1 year. | Inflammatory markers in induced sputum | ||

| Randomized clinical trial Both groups received asthma controllers with the intervention group receiving an additional 100,000-U bolus intramuscularly plus 50,000 U orally weekly of vitamin D weekly |

FEV1 Serum vitamin D levels |

Significant improvement seen in intervention group at 16 weeks | 68 |

| The VIDA randomized, double- blind, parallel, placebo-controlled Trial 201 patients received 100,000 IU once, then 4000 IU/d for 28 weeks and 207 received placebo |

Time to first asthma treatment failure | Vitamin D3 did not reduce the rate of first treatment failure or exacerbation in adults with persistent asthma and vitamin D insufficiency | 69 |

Abbreviations: VIDA-The Vitamin D Assessment; VITAL-Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial; PC20FEV1-20% fall in forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FeNO-Fractional exhaled nitric oxide; IL-Interleukin; IFN-Interferon

Results from Animal Studies

Several in vitro and in vivo studies using animal models have highlighted vitamin D as a potent modulator of the inflammatory response seen in allergic airway inflammation. Vitamin D exerts its effects on structural cells in the airways, cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems as well as guides transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Over the last five years, several animal studies have identified an inverse relationship between vitamin D status and hallmark features of asthma.

As mentioned earlier, vitamin D exerts its effects through the VDR which has been identified on several cells types that mediate allergic airway inflammation. Using a mouse model fed on different vitamin D diets, we have previously shown in our lab that vitamin D deficiency decreased the expression of VDR in the airways of mice following allergen exposure.15 Further examination of hallmark features of asthma revealed that vitamin D deficiency was associated with higher AHR, increased airway remodeling, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) eosinophilia and a reduction in T regulatory cells (Tregs) in the blood when compared to vitamin D sufficient (10,000 IU/kg) groups. Vitamin D deficiency also resulted in increased expression of the NF-κB subunits importin α3 and Rel-A which corresponded with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduced IL-10 levels in BALF.16 In another study to determine whether there is a casual association between vitamin D deficiency, ASM mass and the development of AHR, it was found that vitamin D deficient mice had significantly increased airway resistance and ASM as well as reduced transforming growth factor (TGF)-β levels when compared to the controls.17

It is now well known that structural cells, including epithelial cells and ASM cells contribute to the pathogenesis of asthma via intricate interactions with inflammatory lymphocytes. The loss of airway epithelial integrity and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) during airway remodeling contributes significantly to asthma pathogenesis.18 In a model of toluene diisocyanate (TDI)-induced asthma, it was found that mice that received an intraperitoneal administration of 1,25(OH)2D3 prior to challenge with TDI displayed decreased AHR, suppressed neutrophil and eosinophil infiltration, as well as increased tight junction proteins. In in vitro experiments, treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 was also shown to partial reverse the effects of TDI exposure, namely decline in transepithelial electrical resistance (TER), increase in cell permeability and upregulation of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2.19 Our group has also shown that vitamin D supplementation decreased AHR and infiltration of inflammatory cells in BALF in mice sensitized and challenged with a combination of house dust mite, ragweed and Alternaria. Further examination of the airways in mice that were fed a diet supplemented with 10,000 IU/kg of vitamin D showed increased expression of E-cadherin and decreased expression of vimentin and N-cadherin in airway epithelial cells.20

Several other studies have highlighted a therapeutic role of vitamin D supplementation in the airways of animal models as well as on specific cell types found in the lungs. Intraperitoneal administration of 1,25(OH)2D3 at the time of allergen challenge was shown to attenuate established structural changes in the airways such as goblet cell hyperplasia, increased ASM mass and reduce chronic inflammation in lung tissue as well as decreasing translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus.21 Vitamin D has been demonstrated to promote both Foxp3+ and IL-10 producing CD4+ T-cells. High concentration of 1,25(OH)2D3 resulted in selective expansion of Foxp3+ T regulatory cells over their Foxp3− counterparts. These in vitro studies have been supported by a positive correlation between vitamin D status and CD4+Foxp3+ T-cells in the airways of patients with severe pediatric asthma.22 Vitamin D is also believed to play a role in proliferation and differentiation of another subset of T-cells, Th17 cells. Th17 cells are now known to contribute to AHR and play a role in the recruitment and activation of neutrophils, contributing to neutrophilic asthma.23 In a study examining the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on DC-mediated regulation of Th17 differentiation in OVA-sensitized mice, it was found that increased expression of notch ligand delta-like ligand 4 (Dll4) on DCs resulted in increased Th17 differentiation. Treatment with 1,25-(OH)2D3 was found to decrease this effect.24

Epidemiological data suggest that the low levels of vitamin D during pregnancy and early life contribute to the development of childhood wheezing and asthma. Studies have shown that vitamin D plays a role in fetal lung development and maturation as well as maintaining lung structure and function (reviewed in25). In a rat model aimed at determining the effects of perinatal vitamin D deficiency on pulmonary function, females were put on a special diet (no cholecalciferol or a 250, 500 or 1,000 IU/kg cholecalciferol) one month before pregnancy, which was continued throughout pregnancy and lactation. Results showed that the vitamin D deficient groups had significantly higher airway resistance compared to the two vitamin D supplemented groups (250 and 500 IU/kg). Perinatal vitamin D deficiency was also shown to alter airway contractility and alveolar epithelial-mesenchymal signaling. These effects were blocked by supplementation with 500 IU/kg of vitamin D, suggesting a potential role of perinatal supplementation in the prevention of childhood asthma.26 In another study it was found that adult offsprings born to vitamin D deficient mothers had significantly enhanced lymphocyte proliferation and secretion of cytokines in response to OVA with no modification to other aspects of allergic airway inflammation.27

Although several studies have suggested that vitamin D deficiency exacerbates airway inflammation and its supplementation is useful in alleviating inflammation associated with asthma, some groups have found conflicting evidence. In a study to determine the effects of HDM-induced allergic inflammation on circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D, it was found that the induced inflammation had no effects on vitamin D serum levels.28 In a recent study, BALB/c mice were fed on different vitamin D diets and then sensitized and challenged with house dust mite to determine the effects of vitamin D deficiency on lung structure and function. Results showed that vitamin D deficiency enhanced influx of lymphocytes in BALF, ameliorated HDM-induced increase in ASM mass and protected against increase in baseline airway resistance. RNA-Seq analysis revealed that nine genes were differentially regulated by vitamin D deficiency. Protein expression confirmed that two of the genes, midline 1 (MID1) and adrenomedullin, promoted inflammation, whereas hypoxia-inducible lipid droplet-associated (HILDA), which has been shown to play a role in ASM remodeling, was downregulated.29 Collectively, these results highlight that the effects of vitamin D on HDM-induced allergic inflammation is complex and further studies are needed to better elucidate the potential effects of vitamin D supplementation on lung pathophysiology.

Results from Human Studies

In Vitro Studies

Extensive research done in animal models have highlighted several immunomodulatory effects of vitamin D which have been examined in human cells using in vitro experiments. Since the discovery of the VDR in a plethora of cell types involved in asthma, studies have been aimed at deciphering the mechanisms driving the anti-inflammatory properties of the steroid hormone. Over the last five years, several groups have conducted research on the effects of vitamin D on epithelial cells, ASM cells and T-cells in asthmatic patients.

As seen in animal studies, treatment of passively sensitized human ASM cells (HASM) with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D was found to significantly reduce the binding capacity of NF-κB and inhibited translocation to the nucleus. 1,25(OH)2D3 also increased the stability of IκBα mRNA with reduced phosphorylation of IκBα resulting in increased IκBα expression in these cells.30 In another study aimed at determining the effects of calcitriol in the developing airways of pediatric asthmatics, it was shown that pre-treatment of ASM cells with calcitriol followed by exposure to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α or TGF-β led to attenuation of TNF-α enhancement of MMP-9 expression and activity. Treatment with calcitriol also attenuated TNF-α and TGF-β-induced collagen III expression and deposition and inhibited proliferation of fetal ASM cells mediated by the ERK signaling pathway.31 Characterization of differences in transcriptome responsiveness to vitamin D between fatal asthma and control ASM cells by RNA sequencing have highlighted 838 differentially expressed genes in fatal asthma. Treatment with vitamin D was shown to induce differential expression of 711 genes in fatal asthma and 867 genes in control ASM cells. Genes differentially expressed by vitamin D included those involved in chemokine and cytokine activities. Results highlight vitamin D-specific gene targets and provide novel transcriptomic data that can be used to further explore differences in ASM of patients with fatal asthma.32 It is now well established that the inflammation in asthma involves several subsets of T-lymphocytes, not just Th2 cells. In naïve CD4 T-cells obtained from peripheral blood of young asthmatic subjects as well as healthy controls, it was found that stimulation of these cells under Th17 polarizing conditions led to the production of higher Th17 differentiation in asthmatic patients. The addition of 25(OH)D, in a dose dependent manner, significantly inhibited Th17 cell differentiation in both groups. 25(OH)D-treated DCs were also shown to significantly inhibit IL-17 production and decrease the percentages of CD4+IL-7+ cells in asthmatic patients, highlighting the inhibitory effects on vitamin D on T-cells as well as DCs.33 Recent findings have highlighted a role of Th9 cells in the onset and progression of allergic diseases like asthma. Vitamin D was found to decrease the production of IL-9, IL-5 and IL-8 in cultures where T-helper memory cells were polarized to Th9 cells.34

Vitamin D deficiency has been shown to be associated with lower frequencies of Tregs in the airways. Analysis of blood samples collected from children with asthma (2–6 years old) as well as healthy controls revealed that both concentrations of 25(OH)D and proportions of Treg cells were lower among children with asthma. Conversely, the proportions of B-cells expressing CD23 and CD21 (pairing of both participate in the control of IgE production) were much higher in these patients. Regulatory cytokines, namely IL-10 and TGF-β, as well as vitamin D regulatory enzymes (CYP2R1, CYP27B1) were altered in children with asthma, suggesting impaired immune regulation.35 In another study, stimulation of human CD4+ T-cells with a combination of 1,25(OH)2D3 and TGF-β greatly increased the frequency of FoxP3+ Tregs which is believed to be as a result of enhanced usage and availability of IL-2 by this subset of cells.36 Vitamin D has also been shown to play a role in promoting peripheral tolerance which is critical especially in the airways where excessive inflammation is unwanted. In cell culture studies, treatment of T-cells isolated from human airways with 1α,25VitD3 resulted in upregulation of CD200, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily that delivers an inhibitory signal to immune cells via mediated ligation with CD200R. Results highlight an additional mechanism whereby vitamin D can dampen inflammation in the airways.37

Collectively, the data obtained from in vitro human studies have suggested that vitamin D can modulate inflammation in the innate and adaptive response in the airways. This is however in a controlled environment and require in vivo studies, discussed below, to confirm the benefits of the steroid hormone as a potential therapeutic option.

In vivo Studies

As previously mentioned, vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency are currently on the rise and has been associated with increased asthma morbidity. In a recently concluded nationwide study to examine vitamin D insufficiency, asthma and lung function among US children and adults, it was found that vitamin D insufficiency was associated with current asthma and wheeze in children as well as current asthma in adults. Following analysis by race/ethnicity and current smoking (adults), vitamin D insufficiency was associated with current asthma and wheeze in non-Hispanic white children only whereas in adults, this was seen in non-Hispanic whites and blacks. Vitamin D insufficiency was also associated with lower FEV1 and forced vital capacity in both adults and children. Further analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed that between the years that vitamin D insufficiency decreased, the prevalence of asthma also decreased.38

Children

The prevalence of asthma in children has increased over the last five decades and it is now one of the most common chronic conditions among children under 18 years affecting approximately 6.3 million children worldwide. This increase is believed to be due in part to urbanization and microbial changes in the environment.39 Vitamin D deficiency and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene encoding the VDR have been associated with the development of asthma. To compare vitamin D levels and the frequency of three SNPs in the VDR gene between children with persistent asthma and healthy controls, 25(OH)D levels were measured using radioimmunoassay and SNPs (Apal, Fokl and Taql) analyzed using PCR-RFLP. Overall, no significant differences were found in Apal (rs7975232) and Taql (rs731236) in relationship to vitamin D levels, however a possible association was found between vitamin D sufficiency and Fokl C allele.40 A more recent study has made attempts to shed more light into this subject. A meta-analysis was conducted the determine the relationship between childhood asthma and VDR gene polymorphisms, Apal (rs7975232), Bsml (rs1544410), Fokl (rs2228570) and Taql (rs731236). Of the four SNPs identified, Apal polymorphism is believed to play a role in childhood asthma in Asians, Fokl polymorphism may relate to pediatric asthma in Caucasians, Bsml polymorphisms marginally contributes to susceptibility of childhood asthma and no association was found between Taql and risk of pediatric asthma.41

Several other studies have highlighted a link between vitamin D serum levels and exacerbated symptoms in children with asthma.8,13,42,43 Recently, analysis of 25(OH)D levels in preschoolers aged 1–4 years with asthma as well as healthy subjects showed a significant decrease in vitamin D serum levels of asthmatic children when compared to controls. In the vitamin D sufficient group, total number of exacerbations during the previous year was much lower compared to the vitamin D insufficient group. Frequency of patients with controlled asthma was also higher in the sufficient group suggesting a positive correlation between serum vitamin D levels and asthma control.44

In the last few years, there have been more than a few clinical trials conducted to determine the effects of vitamin D supplementation on clinical outcomes in pediatric asthma. In a recently concluded double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to examine whether vitamin D supplementation could rapidly raise serum 25(OH)D levels in asthmatic preschoolers, it was observed that at 3 months, 100% of the children in the intervention group had serum 25(OH)D levels of ≥75 nmol/L (>30 ng/ml) compared to only about 50% in the control group.45 In another trial with Irish children who received 2000 IU/day of vitamin D for 15 weeks, supplementation led to significant increases in serum 25(OH)D levels and decreased number of missed schools days due to symptoms. There were however no other advantageous changes in asthma parameters compared to the placebo group.46 Assessment of frequency and severity of asthma in Japanese children that were given vitamin D3 supplements (800 IU/day) for 2 months revealed that asthma control was improved by vitamin D supplementation.47

Some studies have however found no evidence to suggest that vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency contributes to overall worse outcome in asthmatic patients. In a recently concluded study aimed at assessing the correlation between vitamin D levels and asthma and allergy markers in non-obese asthmatic children currently not receiving anti-inflammatory treatment, it was found that although the median level of vitamin D was 23 ng/ml, there was no correlation between vitamin D level and airway reactivity, airway inflammation and allergy.42 The World Allergy Organization has recently reported that based on currently available evidence, they found no support for the hypothesis that vitamin D supplementation reduces the risks of developing allergic diseases in children. The panel suggested not using vitamin D in pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers or healthy infants as a means of preventing the developing of allergic diseases.48

Evidence from the highlighted studies have demonstrated an association between vitamin D and lung function. The results from clinical trials have however been inconclusive. More research is needed to conclusively determine if vitamin D insufficiency causes or worsens the onset and symptoms associated with pediatric asthma.

Pregnant Women

Given the early onset of childhood asthma, several studies have been directed at ascertaining the role of maternal diet on the risk of asthma development in offspring. To determine the association of maternal and fetal 25(OH)D levels with lung function and childhood asthma, 25(OH)D levels were measured mid-gestation and at birth and airway resistance measured at 6 years old in offsprings. It was found that maternal levels of 25(OH)D mid-gestation were not associated with airway resistance in offspring at 6 years old. Low levels of 25(OH)D at birth were however associated with higher airway resistance in childhood.49 In a Taiwanese study, there was a significant correlation between maternal and cord blood 25(OH)D levels and persistently lower vitamin D serum levels in children born to vitamin D deficient mothers. Vitamin D deficiency in mothers appeared to be associated with a higher prevalence of allergen sensitization before the age of 2.50 Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled parallel group trial in which women and infants received different doses of vitamin D (400 IU/800 IU in infants and 1000 IU/2000 IU in adults), highlighted that vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and infancy reduces the proportion of children sensitized to mites at 18 months.51

Adults

As seen in meta-analysis studies in children, there is convincing evidence to suggest that polymorphisms in the gene that encodes the VDR are associated with increased susceptibility to asthma.52 Serum 25(OH)D levels of ≤ 30 ng/ml have been found to be common in adults with asthma and more pronounced in patients with severe and/or uncontrolled asthma.53 Individuals with Vitamin D levels of below 50 nmol/L (< 20ng/ml) have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of asthma in Canadian adolescents and adults.54 Analysis of VDBP in BALF and serum as well as 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D3 in serum of patients with mild allergic asthma, showed that VDBP, 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)2D3 were elevated in BALF 24 hours but not ten minutes after allergen challenge. After correction for plasma leakage, VDBP and 25(OH)D were still found to be significantly elevated in BALF 24 hours’ post allergen challenge. These findings suggest that these factors may play a role in the late-phase response in asthma.55 In a Korean study, it was found that low serum 25(OH)D levels were positively associated with total IgE levels which varied based on gender and sensitization to Dermatophagoides farina. Overall, patients with a history of asthma or atopic dermatitis had significantly lower serum 25(OH)D levels than patients who did not suffer from these conditions.56 Results from a retrospective analysis conducted in New Mexico demonstrated that vitamin D sufficiency was significantly associated with decreased total numbers of asthma exacerbations, decreased number of emergency room visits and decrease in total numbers of severe exacerbations.57

In a multi-center, cross-sectional study involving adult patients with inhaled corticosteroid treated asthma in the United Kingdom, lower vitamin D status was associated with higher body mass index, non-White ethnicity, unemployment, lack of use of vitamin D supplements, sampling in Winter or Spring but not with potential genetic determinants. Vitamin D was not found to be associated with any marker of asthma control, namely airway eosinophilia, forced vital capacity and FEV1, investigated. These studies suggest that there is no association between vitamin D status and markers of asthma severity and control which contrasts with results seen in children.58 Similarly in a Danish study, no significant associations where found between serum vitamin D levels and the prevalence or incidence of atopy, asthma or wheezing in adults.59

In the recently concluded HUNT study in Norway, participants with low 25(OH)D were observed to have more decline in lung function measurements for FEV1, forced vital capacity and FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio compared to those with high serum vitamin D levels. Low serum 25(OH)D levels were found to be only weakly associated with decline in lung function in adults with asthma.60

Viral respiratory tract infections have been shown to play a role in the onset, progression and exacerbation of allergic diseases like asthma.61 In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled control trial in London, asthmatic patients were given six 2-monthly doses of 3 mg of vitamin D or placebo to determine the effects of vitamin D supplementation on the prevention of exacerbations and upper respiratory tract infections. Results suggest that vitamin D supplementation had no effect on exacerbations or upper respiratory tract infections in patients.62 Collectively, these studies suggest that there exists a causal relationship between vitamin D and asthma. However, there is the need for more targeted studies to better determine the exact nature of this relationship.

Conclusions and Future Prospects

Vitamin D has been shown to be a potent immunomodulator of the immune response in several inflammatory diseases. Despite increased knowledge gained from research and fortification of certain foods with vitamin D, vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency are still prevalent in many developed countries. The role of vitamin D in asthma pathogenesis is still a topic of much debate. Results from animal studies and in vitro studies using human cells have shown an immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D supplementation in controlling inflammation mediated by cells in the asthmatic response (Figure 1). Several epidemiological and in vivo studies have found a link between low serum levels of vitamin D and increased inflammation, decline in lung function, increased exacerbations and overall poor outcome in patients with asthma. Although vitamin D supplementation has appeared to be a viable option for adjunct therapy, results from clinical trials have primarily shown that supplementation has very little, if any, effect on improvement of symptoms or onset of asthma in patients (Table 1). It is important to note that these clinical trials are not without limitations. Limited sample sizes as well as variations in dosage and the duration of trials are all factors which may have contributed to some of the observed results. Clearly, there is still a great deal of work to be done in the field. Studies are first needed to clearly define the most optimal technique for measuring serum vitamin D levels and arrive at some consensus for what is described as vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency. Additionally, future research needs to identify the optimal dose of vitamin D for distinct groups based on gender, ethnicity, age, cultural practices and asthmatic phenotype since all these factors affect absorption and available levels of vitamin D. Moving forward, clinical trials need to be better designed to ensure that all these factors as well as route of administration for optimal results are considered when designing interventional studies. If these factors are addressed, the results obtained from future trials should be more conclusive and finally give better insights as to whether vitamin D supplementation is indeed the light at the end of the tunnel we so desperately desire.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants R01 HL112597, R01 HL116042, and R01 HL120659 to DK Agrawal from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA. The content of this review article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hall SC, Fischer KD, Agrawal DK. The impact of vitamin D on asthmatic human airway smooth muscle. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2016;10(2):127–135. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2016.1128326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loftus PA, Wise SK. Epidemiology and economic burden of asthma. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5(Suppl 1):S7–10. doi: 10.1002/alr.21547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fergeson JE, Patel SS, Lockey RF. Acute asthma, prognosis, and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barragan M, Good M, Kolls JK. Regulation of dendritic cell function by vitamin D. Nutrients. 2015;7(9):8127–8151. doi: 10.3390/nu7095383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berraies A, Hamzaoui K, Hamzaoui A. Link between vitamin D and airway remodeling. J Asthma Allergy. 2014;7:23–30. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S46944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirzakhani H, Al-Garawi A, Weiss ST, Litonjua AA. Vitamin D and the development of allergic disease: How important is it? Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):114–125. doi: 10.1111/cea.12430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yawn J, Lawrence LA, Carroll WW, Mulligan JK. Vitamin D for the treatment of respiratory diseases: Is it the end or just the beginning? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;148:326–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kerley CP, Elnazir B, Faul J, Cormican L. Vitamin D as an adjunctive therapy in asthma. part 2: A review of human studies. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;32:75–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerley CP, Elnazir B, Faul J, Cormican L. Vitamin D as an adjunctive therapy in asthma. part 1: A review of potential mechanisms. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;32:60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstantinopoulou S, Tapia IE. Vitamin D and the lung. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bozzetto S, Carraro S, Giordano G, Boner A, Baraldi E. Asthma, allergy and respiratory infections: The vitamin D hypothesis. Allergy. 2012;67(1):10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thacher TD, Clarke BL. Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(1):50–60. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta A, Bush A, Hawrylowicz C, Saglani S. Vitamin D and asthma in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2012;13(4):236–43. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2011.07.003. quiz 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tizaoui K, Berraies A, Hamdi B, Kaabachi W, Hamzaoui K, Hamzaoui A. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with asthma risk: Systematic review and updated meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lung. 2014;192(6):955–965. doi: 10.1007/s00408-014-9648-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agrawal T, Gupta GK, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D deficiency decreases the expression of VDR and prohibitin in the lungs of mice with allergic airway inflammation. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;93(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal T, Gupta GK, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D supplementation reduces airway hyperresponsiveness and allergic airway inflammation in a murine model. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(6):672–683. doi: 10.1111/cea.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foong RE, Shaw NC, Berry LJ, Hart PH, Gorman S, Zosky GR. Vitamin D deficiency causes airway hyperresponsiveness, increases airway smooth muscle mass, and reduces TGF-beta expression in the lungs of female BALB/c mice. Physiol Rep. 2014;2(3):e00276. doi: 10.1002/phy2.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pain M, Bermudez O, Lacoste P, et al. Tissue remodelling in chronic bronchial diseases: From the epithelial to mesenchymal phenotype. Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(131):118–130. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00004413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Dong H, Zhao H, et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 prevents toluene diisocyanate-induced airway epithelial barrier disruption. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36(1):263–270. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer KD, Hall SC, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D supplementation reduces induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in allergen sensitized and challenged mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai G, Wu C, Hong J, Song Y. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) (1,25-(OH)(2)D(3)) attenuates airway remodeling in a murine model of chronic asthma. J Asthma. 2013;50(2):133–140. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.738269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Urry Z, Chambers ES, Xystrakis E, et al. The role of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and cytokines in the promotion of distinct Foxp3+ and IL-10+ CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(10):2697–2708. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall S, Agrawal DK. Key mediators in the immunopathogenesis of allergic asthma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;23(1):316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Y, Zhao S, Yang X, Liu Y, Wang C. Dll4 in the DCs isolated from OVA-sensitized mice is involved in Th17 differentiation inhibition by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in vitro. J Asthma. 2015;52(10):989–995. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1056349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comberiati P, Tsabouri S, Piacentini GL, Moser S, Minniti F, Peroni DG. Is vitamin D deficiency correlated with childhood wheezing and asthma? Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2014;6:31–39. doi: 10.2741/e687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yurt M, Liu J, Sakurai R, et al. Vitamin D supplementation blocks pulmonary structural and functional changes in a rat model of perinatal vitamin D deficiency. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307(11):L859–67. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00032.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorman S, Tan DH, Lambert MJ, Scott NM, Judge MA, Hart PH. Vitamin D(3) deficiency enhances allergen-induced lymphocyte responses in a mouse model of allergic airway disease. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(1):83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Perks KL, Stick SM, Kicic A, Larcombe AN, Zosky G. House dust mite induced lung inflammation does not alter circulating vitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foong RE, Bosco A, Troy NM, et al. Identification of genes differentially regulated by vitamin D deficiency that alter lung pathophysiology and inflammation in allergic airways disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2016;311(3):L653–63. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00026.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song Y, Hong J, Liu D, Lin Q, Lai G. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits nuclear factor kappa B activation by stabilizing inhibitor IkappaBalpha via mRNA stability and reduced phosphorylation in passively sensitized human airway smooth muscle cells. Scand J Immunol. 2013;77(2):109–116. doi: 10.1111/sji.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Britt RD, Jr, Faksh A, Vogel ER, et al. Vitamin D attenuates cytokine-induced remodeling in human fetal airway smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(6):1189–1198. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Himes BE, Koziol-White C, Johnson M, et al. Vitamin D modulates expression of the airway smooth muscle transcriptome in fatal asthma. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0134057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamzaoui A, Berraies A, Hamdi B, Kaabachi W, Ammar J, Hamzaoui K. Vitamin D reduces the differentiation and expansion of Th17 cells in young asthmatic children. Immunobiology. 2014;219(11):873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keating P, Munim A, Hartmann JX. Effect of vitamin D on T-helper type 9 polarized human memory cells in chronic persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(2):154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chary AV, Hemalatha R, Murali MV, Jayaprakash D, Kumar BD. Association of T-regulatory cells and CD23/CD21 expression with vitamin D in children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;116(5):447–454.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chambers ES, Suwannasaen D, Mann EH, et al. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in combination with transforming growth factor-beta increases the frequency of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells through preferential expansion and usage of interleukin-2. Immunology. 2014;143(1):52–60. doi: 10.1111/imm.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dimeloe S, Richards DF, Urry ZL, et al. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 promotes CD200 expression by human peripheral and airway-resident T cells. Thorax. 2012;67(7):574–581. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han YY, Forno E, Celedon JC. Vitamin D insufficiency and asthma in a US nationwide study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smits HH, van der Vlugt LE, von Mutius E, Hiemstra PS. Childhood allergies and asthma: New insights on environmental exposures and local immunity at the lung barrier. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;42:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Einisman H, Reyes ML, Angulo J, Cerda J, Lopez-Lastra M, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Vitamin D levels and vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in asthmatic children: A case-control study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(6):545–550. doi: 10.1111/pai.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao DD, Yu DD, Ren QQ, Dong B, Zhao F, Sun YH. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to childhood asthma: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ppul.23548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dabbah H, Bar Yoseph R, Livnat G, Hakim F, Bentur L. Bronchial reactivity, inflammatory and allergic parameters, and vitamin D levels in children with asthma. Respir Care. 2015;60(8):1157–1163. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hollams EM. Vitamin D and atopy and asthma phenotypes in children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(3):228–234. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283534a32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turkeli A, Ayaz O, Uncu A, et al. Effects of vitamin D levels on asthma control and severity in pre-school children. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20(1):26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen ME, Mailhot G, Alos N, et al. Vitamin D intervention in preschoolers with viral-induced asthma (DIVA): A pilot randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17(1):353-016–1483-1. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1483-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerley CP, Hutchinson K, Cormican L, et al. Vitamin D3 for uncontrolled childhood asthma: A pilot study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(4):404–412. doi: 10.1111/pai.12547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tachimoto H, Mezawa H, Segawa T, Akiyama N, Ida H, Urashima M. Improved control of childhood asthma with low-dose, short-term vitamin D supplementation: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71(7):1001–1009. doi: 10.1111/all.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yepes-Nunez JJ, Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, et al. World allergy organization-McMaster university guidelines for allergic disease prevention (GLAD-P): Vitamin D. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:17-016–0108-1. doi: 10.1186/s40413-016-0108-1. eCollection 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gazibara T, den Dekker HT, de Jongste JC, et al. Associations of maternal and fetal 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with childhood lung function and asthma: The generation R study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46(2):337–346. doi: 10.1111/cea.12645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiu CY, Huang SY, Peng YC, et al. Maternal vitamin D levels are inversely related to allergic sensitization and atopic diseases in early childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(4):337–343. doi: 10.1111/pai.12384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grant CC, Crane J, Mitchell EA, et al. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and infancy reduces aeroallergen sensitization: A randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1325–1334. doi: 10.1111/all.12909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han JC, Du J, Zhang YJ, et al. Vitamin D receptor polymorphisms may contribute to asthma risk. J Asthma. 2016;53(8):790–800. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2016.1158267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Korn S, Hubner M, Jung M, Blettner M, Buhl R. Severe and uncontrolled adult asthma is associated with vitamin D insufficiency and deficiency. Respir Res. 2013;14:25-9921–14-25. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niruban SJ, Alagiakrishnan K, Beach J, Senthilselvan A. Association between vitamin D and respiratory outcomes in canadian adolescents and adults. J Asthma. 2015;52(7):653–661. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1004339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bratke K, Wendt A, Garbe K, et al. Vitamin D binding protein and vitamin D in human allergen-induced endobronchial inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;177(1):366–372. doi: 10.1111/cei.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang JW, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Lee JG, Yoon JH, Kim CH. Association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D with serum IgE levels in korean adults. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43(1):84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salas NM, Luo L, Harkins MS. Vitamin D deficiency and adult asthma exacerbations. J Asthma. 2014;51(9):950–955. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.930883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jolliffe DA, Kilpin K, MacLaughlin BD, et al. Prevalence, determinants and clinical correlates of vitamin D deficiency in adults with inhaled corticosteroid-treated asthma in london, UK. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thuesen BH, Heede NG, Tang L, et al. No association between vitamin D and atopy, asthma, lung function or atopic dermatitis: A prospective study in adults. Allergy. 2015;70(11):1501–1504. doi: 10.1111/all.12704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brumpton BM, Langhammer A, Henriksen AH, et al. Vitamin D and lung function decline in adults with asthma: The HUNT study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(8):739–746. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Busse WW, Lemanske RF, Jr, Gern JE. Role of viral respiratory infections in asthma and asthma exacerbations. Lancet. 2010;376(9743):826–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61380-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martineau AR, MacLaughlin BD, Hooper RL, et al. Double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial of bolus-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in adults with asthma (ViDiAs) Thorax. 2015;70(5):451–457. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gold DR, Litonjua AA, Carey VJ, et al. Lung VITAL: Rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of an ancillary study evaluating the effects of vitamin D and/or marine omega-3 fatty acid supplements on acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory disease, asthma control, pneumonia and lung function in adults. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;47:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Litonjua AA, Carey VJ, Laranjo N, et al. Effect of prenatal supplementation with vitamin D on asthma or recurrent wheezing in offspring by age 3 years: The VDAART randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(4):362–370. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chawes BL, Bonnelykke K, Stokholm J, et al. Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation during pregnancy on risk of persistent wheeze in the offspring: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(4):353–361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Denlinger LC, King TS, Cardet JC, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colds in patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(6):634–641. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201506-1169OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bar Yoseph R, Livnat G, Schnapp Z, et al. The effect of vitamin D on airway reactivity and inflammation in asthmatic children: A double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(8):747–753. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Arshi S, Fallahpour M, Nabavi M, et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on airway functions in mild to moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(4):404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castro M, King TS, Kunselman SJ, et al. Effect of vitamin D3 on asthma treatment failures in adults with symptomatic asthma and lower vitamin D levels: The VIDA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(20):2083–2091. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]