Seeing a police officer evokes different emotions for different people in the United States. Some react with a sense of vicarious pride, respecting the officer’s sacrifice for working in a potentially dangerous job to protect the safety of the public. Some react with neutrality, assuming that the police are there for the “others”—the criminals or the victims, of which they are neither. Finally, a significant number of Americans appears to react with fear, apprehension, and an acute sense of urgency and danger.

These different ways of viewing the police are not evenly distributed across the population, and perhaps the best predictor of how one views the police may be one’s own race/ethnicity. We see this in media reports depicting the killing of African Americans by police officers. We see this when African American mothers and fathers give their children “the talk” by teaching them how to safely interact with police officers when confronted. Lagging far behind this shared cultural sense of distrust, we are beginning to see a growing awareness among health practitioners, policymakers, and other stakeholders that police mistreatment is an important public health problem.

INTERACTIONS WITH RACIAL/ETHNIC MINORITIES

Recently, concern about police interactions with racial/ethnic minorities has intensified as a result of several high-profile cases that showed police officers using excessive force against citizens of color. Such incidences have highlighted the potentially harmful effects of police practices based on racial profiling procedures toward racial/ethnic minorities, especially African American males. Although concerns about police interactions with racial/ethnic minorities are not new, these recent publicized cases generally corroborated the view that racial/ethnic minority men are “the primary targets of negative police experiences.”1

In addition to studying the strained relationships between the police and racial/ethnic minority communities, public health researchers have begun to examine the health consequences of law enforcement policies and practices. For example, the American Public Health Association recently issued a statement declaring “law enforcement violence” to be a critical but nevertheless underexamined public health issue (bit.ly/2qLcSLY).

Although emerging evidence shows that police abuse is associated with distress, depression, anxiety, and trauma symptoms in US populations,2,3 no studies have yet examined this topic using nationally representative survey data on African American households—the demographic group purported to be at highest risk for this exposure to harmful police practices.

MENTAL HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

We analyzed the National Survey of American Life4 to explore the mental health significance of unfair treatment or abuse by police among African American adults. The National Survey of American Life contains a national household probability subsample of African Americans (n = 3570; response rate = 70.7%) who were assessed using the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (https://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi). The survey elicited information about police mistreatment or abuse with the following dichotomous item: “Have you ever been unfairly stopped, searched, questioned, physically threatened, or abused by the police?” In the entire African American subsample of the National Survey of American Life, 27.94% (weighted) reported experiencing police mistreatment or abuse at some point in life, which is an alarmingly common occurrence.

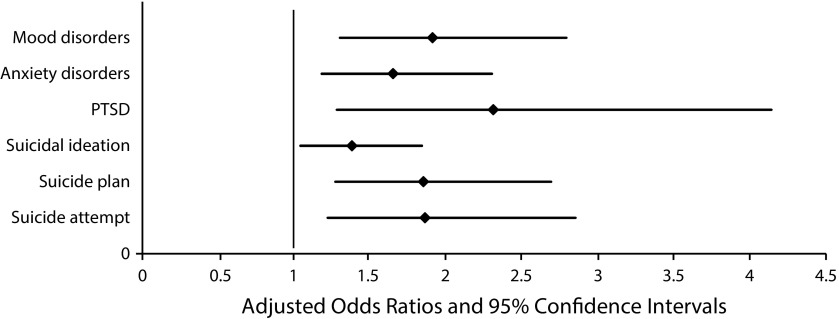

Furthermore, we discovered that police mistreatment or abuse was more prevalent among respondents with psychiatric disorders and was associated with greater odds of having 12-month mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder after we adjusted for sociodemographic covariates (Figure 1). These associations were apparent even after we controlled for alcohol and substance use disorders (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition5), which are important confounders, given that alcohol and substance abuse and dependence frequently co-occur with mental health issues and may draw police attention.

FIGURE 1—

Associations Between Lifetime Police Abuse and Mental Health Outcomes: US National Survey of American Life, 2001–2003

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Police mistreatment or abuse also was associated with greater odds of reporting lifetime suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts, after we adjusted for sociodemographic covariates and lifetime psychiatric disorders (Figure 1). When we restricted analyses to only those individuals who reported lifetime suicidal ideation (n = 395), police abuse was associated with increased odds of reporting a lifetime suicide attempt (odds ratio = 2.00; 95% confidence interval = 1.07, 3.74; P = .03), after we adjusted for sociodemographic covariates and psychiatric disorders. Additional information can be found in the supplemental material (available with the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

OFFICER TRAINING AND ACCOUNTABILITY

Overall, we found strong evidence that experiencing at least one incident of police mistreatment or abuse was associated with major psychiatric disorders over the past year and suicidal behaviors at some point in life among African Americans. However, because of the cross-sectional nature of our analyses, we could not make strong causal inferences; thus, two explanations are possible.

The first explanation is that individuals who have mental health problems may increase the risk of experiencing police mistreatment or abuse. Police officers often respond to mental health crises in the community, but are often inadequately trained for these situations, resulting in mistreatment or abuse.6 In this case, police officers should receive comprehensive training on how to interact with people with mental illnesses and must work with other practitioners (e.g., mobile crisis units) to ensure the physical or psychological safety of the person in crisis.6

A second explanation is that police mistreatment or abuse can result in stress and trauma, injuring the mind via the stress-response system, which then becomes manifested in various psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviors.7 In this case, we must further examine the extent to which police practices and interactions with African Americans result in stressful situations that operate as risk factors for mental illnesses and suicidal behaviors. To mitigate these public health consequences, it is imperative to conduct screenings and refer people who experience police mistreatment and abuse to mental health professionals and advocacy groups. Also, police officers need additional training, and accountability structures must be developed, while allowing space for procedural and community-based restorative justice approaches.

In some ways, our inability to make strong causal inferences about our findings is inconsequential because the two possible explanations we have discussed are not mutually exclusive, and both point us in the same general direction. Broadly speaking, both explanations call for systemic changes toward improved police officer training and accountability, with the hope of ameliorating the current strained relationships between many police departments and the communities of color they serve. Both explanations compel us to conduct interdisciplinary research to investigate the effect of policing on the physical and mental health of African Americans.

In the next few years, public health professionals may be asked to grapple with this issue more deeply than ever, so we should begin to consider—and even innovate—concrete strategies that enable the police to protect and serve the public as equitably as possible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Preparation of this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; grant T32AA014125).

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or National Institutes of Health.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Secondary analyses were conducted with data from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys, which were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan, Harvard University, Cambridge Health Alliance, and University of Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brunson RK, Miller J. Gender, race, and urban policing: the experience of African American youths. Gend Soc. 2006;20(4):531–552. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeVylder JE, Oh HY, Nam B, Sharpe TL, Lehmann M, Link BG. Prevalence, demographic variation and psychological correlates of exposure to police victimisation in four US cities. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;11:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016000810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geller A, Fagan J, Tyler T, Link BG. Aggressive policing and the mental health of young urban men. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(12):2321–2327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH et al. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, DeCuir WJ., Jr The police and mental health. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(10):1266–1271. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter RT. Racism and psychological and emotional injury: recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. Couns Psychol. 2007;35(1):13–105. [Google Scholar]