Toxic Inequality: How America’s Wealth Gap Destroys Mobility, Deepens the Racial Divide, & Threatens Our Future By Thomas M. Shapiro

New York, NY: Basic Books; 2017 288 pp.; $15.12 ISBN-13: 978-0465046935

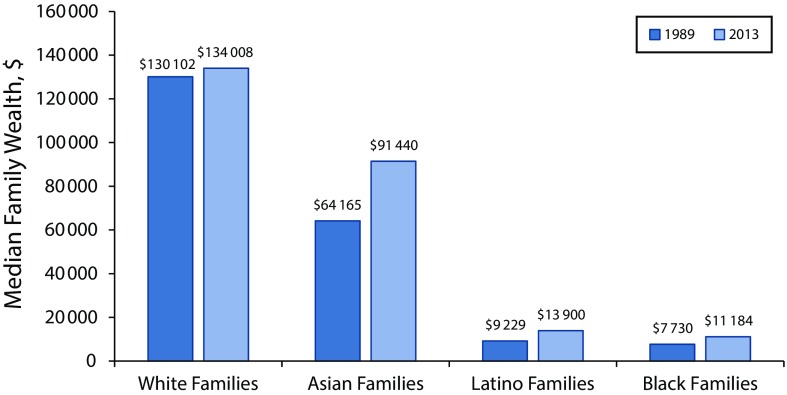

Toxicity, inequity, and inequality are powerful words in the public health lexicon and are increasingly dominating the public discourse as explanatory factors for health outcomes and their relationship to public resources, neighborhood contexts, and place-based quality of care in the United States. The central premise of Shapiro’s book is that inequality is driven not by differing attitudes, values, and characteristics that promote or hinder achievement among rich, middle-income, and poor populations, but rather by income and wealth gaps (Figure 1) and inequitable public policies (structural racism) that were designed to advantage one group over another. For his book, Shapiro conducted interviews of 187 Black and White families, three fourths of whom identified as middle class and more than 50% of whom were college educated, over a 12-year interval.

FIGURE 1—

Racial/Ethnic Wealth Gap: US Median Family Wealth, 1989 and 2013

MAJOR ADVERSE LIFE EVENTS

Shapiro, a sociologist, uses different case examples of Black and White families to proffer major decision-making event narratives. He repeatedly found that when Black families experience major life events such as loss of a job or illness, these events often create insurmountable obstacles owing to a lack of access to economic or social resources and institutional policy support systems. Black families are less likely than White families to have family-of-origin assets from which to draw (i.e., family loans) and are more likely to have jobs that provide fewer benefits; also, they tend to live in neighborhoods that are less safe, have lower home equities, and have less resourced school systems. His analyses dig deeply into how schooling and employment are shaped by family-of-origin race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status and how these factors strongly influence opportunities throughout the life course.

Shapiro astutely weaves in and out of the lives of individuals and shows how Whites who come from backgrounds of higher socioeconomic status are able, with both institutional support (e.g., extensive employment rewards) and family resources, to more successfully confront major adverse life events. At the simplest level of analysis, he documents social determinants and the role of inequity with respect to what it means to be Black or Mexican American as well as the persistent barriers that sustain the wealth gap, lead to a lower quality of life, and produce more adverse health events and outcomes.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS

In 1899, Dubois1 described differences in health outcomes associated with place (e.g., zip code, community residence), socioeconomic status, and race. Since the early 20th century, public health scholars have developed a more comprehensive paradigm to explain differences in these outcomes. Moving beyond the concept of complexity, the field settled on social determinants as a meaningful and powerful paradigm. Shapiro builds unwittingly on the discourse of social determinants and focuses primarily on the critical nexus of history, race/ethnicity, and policy. He speaks to the “toxic inequality syndrome,” that is, the emotional and physiological consequences of everyday racism, persistent economic trauma, adversity, closed opportunity structures, and exclusionary national policies (p. 19).

The tentacles of racism are crystallized and include differences in institutional allocation of resources (parks, employment-related benefits, housing values). Shapiro demonstrates the invisible impact of racism on access to opportunities and the ways in which social interpretations of how we look and where we live (e.g., predatory lending) inform policies and practices. “Today federal policy privileges already-amassed wealth, redistributes opportunities to accumulate wealth to those at the top, and helps the wealthy maintain wealth over time, and pass it along to their children” (p. 179). His central argument is that individuals are hampered by discriminatory public policies. By contrast, Rostila2 described political generosity as the means by which government welfare programs can promote social capital and eventually improve health.

In chapter 5, Shapiro sharply articulates the historic and biased rules and regulations of current public policies that continue to advantage some groups over others in the areas of housing, public assistance, higher education, employment (benefits and protections), and public health (health insurance affordability, comprehensive community health centers, reproductive health services). The undeniable racial and class inequities described in the chapter “Hidden Hand of Government” play a significant role in the health and mental health of the US population, particularly the country’s historically underrepresented groups. In the final chapter, Shapiro proposes well-known and evidence-based solutions such as universal preschool, universal health care, and a living wage.

HISTORIC INJUSTICE

These descriptive analyses inform the public health discourse in several ways. For example, neighborhoods of opportunity matter because they include, among other advantages, higher quality housing, better food markets, and better air quality.3 Also, employment without a living wage and health benefits hurts families and communities; low-resourced and poor-quality schools, dependent on a real estate tax base, create unequal opportunities; and, without significant changes in public social policies, health inequities and disparities will remain relatively unchanged. Moreover, the author’s findings showcase, indirectly though poignantly, how “wealth and race map together to consolidate historic injustice . . . creating an increasingly divided opportunity structure” (p. 18).

This work contributes evidence to Marmot’s4 integrated framework in support of how life stressors, including discrimination and unstable incomes, contribute to adverse physical and mental health outcomes. Marmot argued that relative differences in status translate to absolute differences in life chances.

ACCESS, OPPORTUNITY, AND JUST REWARDS

Shapiro’s narrative approach is refreshing as it deepens the notion of “complexity” in the field of public health and illuminates the critical ways in which policies often increase the economic and resource divide through inequitable allocation of benefits and advantages. The public health agenda cannot move forward if we continue to study populations experiencing historic and unhealthy material conditions and policy constraints without acknowledging historic problems in race relations and disadvantageous public policies.5 The author concludes, smartly so, “At its heart, inequality is about access, opportunity and just rewards” (p. 218). The question for us in public health is the following: How do we use the largesse of our knowledge tool kit to change the toxic policy conditions that so adversely affect the health and mental health of the US population?

REFERENCES

- 1.DuBois WEB. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. New York, NY: Schocken; 1899. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rostila M. Social Capital and Health Inequality in European Welfare States. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acevedo-Garcia D, Osypuk TL, McArdle N, Williams DR. Toward a policy-relevant analysis of geographic and racial/ethnic disparities in child health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(2):321–333. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot MG. Status syndrome: a challenge to medicine. JAMA. 2006;295(11):1304–1307. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.11.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley A. Neighborhood disadvantage, residential segregation, and beyond—lessons for studying structural racism and health. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0378-5. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]