Abstract

Objective. To evaluate changes in pharmacy and nursing student perspectives before and after completion of an interprofessional education (IPE) course.

Methods. A pre- and post-perception scale descriptive prospective study design utilizing Interdisciplinary Education Perception Scale (IEPS) and Collaboration and Satisfaction about Care Decisions (CSACD) with self-reported statements of knowledge and importance of professional roles was used.

Results. Significant improvement was shown for IEPS and CSACD overall and for both pharmacy and nursing students. Post-scores improved from 2013 to 2014, with significant improvements for IEPS. Pharmacy student findings show an increase in knowledge and importance of their roles and those of nursing students. Nursing students grew significantly in their knowledge of the pharmacist’s role only.

Conclusion. An IPE course for nursing and pharmacy students, taught by diverse health professionals with a care plan and simulation assignments, fosters the Interprofessional Education Collaborative panel’s competencies for IPE.

Keywords: interprofessional education, interdisciplinary education, pain, nursing students, pharmacy students

INTRODUCTION

Health care that is patient-centered, high quality, has positive outcomes, and is delivered with efficiency and seamless coordination, is what patients expect. To reach this goal, health care providers rely on an interprofessional team-based patient care to be well-orchestrated, coordinated, and complete. One method of preparing students to become effective practitioners in team-based health care is to create interprofessional education (IPE) opportunities in student education.1

Interprofessional education has been discussed for decades within schools of health care professions and within their accreditation bodies, compelling educators to include IPE into school competencies and accreditation standards.2 Beyond schools and universities, the World Health Organization,3 the Institutes of Medicine,4,5 and a global, independent commission on health professional education have expressed support for IPE.6

Many universities host numerous health science profession programs, with students in each program sharing some common educational ground, albeit taught independently. Students may not learn as an interprofessional team until they meet outside of the educational institution in clinical practice sites, where they may lack confidence or are unprepared for team-based health care, highlighting a learning gap between didactic and experiential learning.

Interprofessional education, as a pedagogical approach, can bridge this gap,7 beginning with the concept of learning with, from, and about two or more professions.3,8 IPE, as a method of preparing students for current practice models, has been reported to improve students’ collaboration, confidence, and critical thinking skills.9 For patients, increased cost efficiency and reduced medical errors may arise from interprofessional teamwork. Health care professionals also may experience increased satisfaction.10

This study was conducted at Duquesne University, a private, Catholic institution in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with an enrollment of nearly 10,000 students in nine schools of study, including the schools of nursing and pharmacy. An interprofessional elective course, Etiology, Assessment and Treatment of Pain for the Health Care Professional, was created in the spring 2013 semester for senior nursing students and third professional year (fifth year) pharmacy students. Utilizing the curricular theme of the treatment of pain, the expectation was for students to develop confidence and preparedness for work in interprofessional teams.

A registered nurse and a registered pharmacist, both full-time faculty in their respective schools as well as current practitioners, coordinated the course with faculty from Duquesne’s schools of health professions and sciences, and team-based local practitioners. Team activities included patient care simulations, interprofessional care planning, and a reflective assignment. These were designed to enhance student proficiency within one or more of the core IPEC competencies: values and ethics for interprofessional practice; roles and responsibilities of health care professionals; interprofessional communication; and teams and teamwork.11

The objective of this study was to evaluate changes in student perspectives and knowledge after students participated in interprofessional teamwork in an IPE class designed to increase their knowledge of pain and identification of the professional roles of nursing and pharmacy students in pain care.

The list of obstacles to overcome on the journey to comprehensive IPE in a university include: programs contained within educational silos, turf wars, logistics, identification of appropriate curricular themes, historical entrenchment, embedded biases and hierarchy, faculty development, and resources.12-15 This is not to say that students have not experienced instances of IPE, nor is it to say that universities have not enjoyed successes or have found the IPE program accreditation standards to be unobtainable.16-21 In our institution, the schools of nursing and pharmacy operate independently under the leadership of two deans and in separate buildings on campus, a distance from each other. Identifying a unifying theme for the course, common student pre-requisites, physical and curricular time and space considerations, course registration, merging the learning management system, and defining a common language between professions were the initial hurdles for the course development.

As each health care provider is well-trained within their specialty, employing IPE in the curriculum can advance the competency of students for their team-based roles in health care practice and prepare them to be team-ready and practice-ready. Competencies related to the roles and responsibilities of differing professionals are critical to effective team functioning and provision of quality patient care.22 Reports of IPE have examined participants’ perceptions of other disciplines23,24 or knowledge of their professional role.25,26 However, little is known about how an IPE course may affect student knowledge of other professionals’ roles, and some evidence suggests that students may have misconceptions about the roles of other health care professions.27 The changes in student perspectives and knowledge of these roles after a semester-long IPE active learning course experience is the value of an IPE course.

METHODS

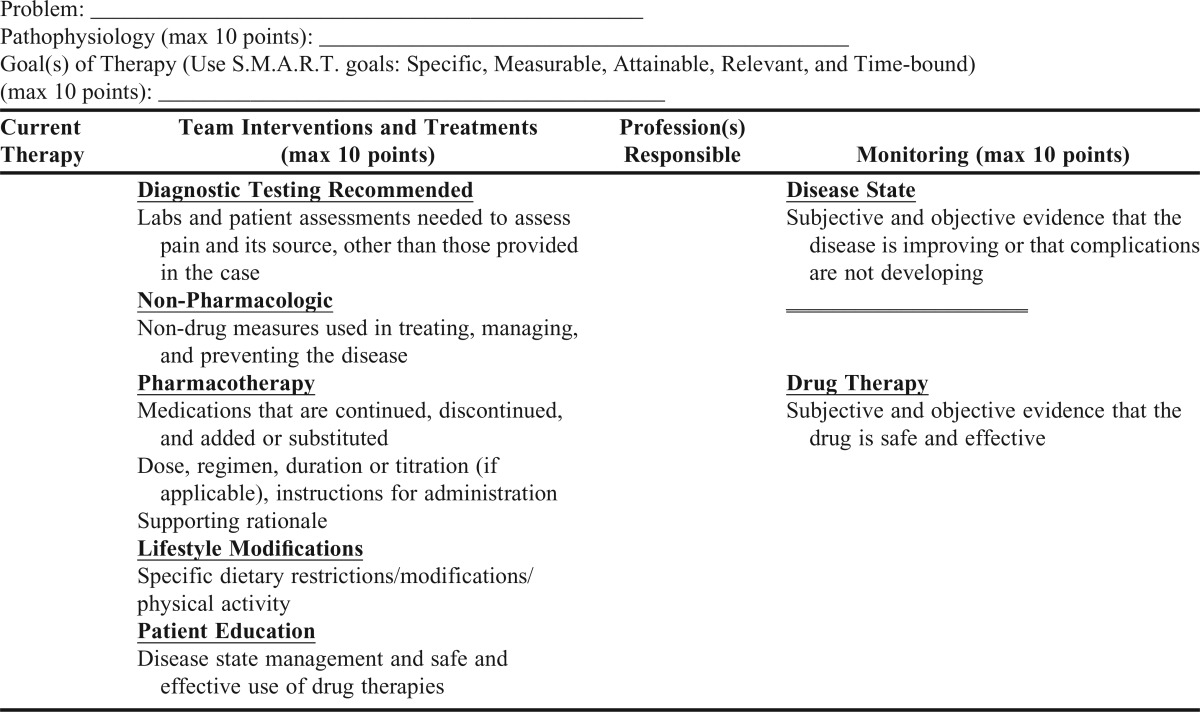

This three-credit course consisted of presentations from multiple professionals, including a physical therapist, physician assistant, clinical nurse specialist, critical care clinical pharmacist, emergency department pharmacist, and registered nurse, to name a few. Most of the presentations were about their role in pain management for chronic and acute pain, and a few science faculty presented on pain pathways, anatomy, mechanisms of action for treatment options. Other presentations helped establish a common knowledge base from which to discuss the topic of pain. The class consisted of nursing and pharmacy students. The students were divided into three to four interprofessional work groups, with a representative sample of nursing and pharmacy students. The work groups completed the IPE assignments and activities together during the entire semester. The final assignment included the development of an interprofessional care plan for a patient with acute pain (kidney stone, hip fracture and repair, median sternotomy) and chronic pain (osteoarthritis, low back pain, chronic cholelithiasis) (Appendix 1). To prepare for the interprofessional assignments, teams viewed a video, produced by the faculty, during physical and verbal interaction with a high fidelity SimMan (HFSM) experiencing cancer pain. Students then suggested improvements to the actions of the nurse and pharmacist in the video.

The students also participated in simulations as an interprofessional team. The simulations were conducted with a standardized patient and with a HFSM. The first class of students in spring 2013 participated in one simulation on sickle cell crisis with the HFSM. The student evaluations of the faculty and course administered by the university at the end of each semester included student suggestions to include more simulation experiences in the course. During the second offering of the course, the number of simulations was increased from one to four. The first simulation employed a standardized patient with osteoarthritis and was a fall risk. The following three simulations utilized HFSM for a patient with 65% total body surface area burn, a patient with low back pain suffering from an ischemic stroke, and a sickle cell patient in crisis, which was the same simulation in the first year of the course. The background, past medical history, home medications, vital signs, age, weight, height, laboratory values, and physician orders were given to the students prior to each simulation.

This was a pre- and post-perception scale descriptive prospective study. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval at Duquesne University was obtained for this study, and all students provided written informed consent. Students in the spring 2013 and spring 2014 elective course, Etiology, Assessment and Treatment of Pain for the Health Care Professional, were asked to participate. Students were senior nursing students in a four-year baccalaureate nursing program, and third-year professional (fifth year) pharmacy students in a six-year PharmD program. These academic levels were chosen based on common educational backgrounds at this point in their education and the availability of electives in each curriculum. Students were informed that their grade in this class would not be affected whether they participated or not in this research, that their name or identifiers would not appear on any survey or research instruments, and that their responses would only appear in statistical data summaries. Students who agreed to participate completed the Interdisciplinary Education Perception Scale (IEPS), Collaboration and Satisfaction about Care Decisions (CSACD), demographic information, and perceptions of the role and importance of registered nurses and pharmacists in patient pain management.

During class time on the first and last day of class, participating students completed a form that consisted of 10 short answer questions about demographic characteristics along with seven Likert-style statements (responses ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree) to collect pre- and post-course self-reported knowledge and importance of their role in the treatment of pain and the role of the other profession represented in the course. Students also completed two validated data collection tools, IEPS and CSACD. The IEPS28 consists of 18 Likert-style statements originally published by Luecht and colleagues (1990). It is considered to be a perceptual/attitudinal inventory for use with a health care/student population. The measure was designed initially as a pre/post-assessment of students’ involved in an IPE experience. Luecht and colleagues identified four domains of the IEPS: competency and autonomy (items 1,3-5, 7, 9, 10, and 13); perceived need for cooperation (items 6 and 8); perception of actual cooperation (items 2, 14-17); and understanding others’ value (items 11, 12, 18).28 The CSACD is another Likert-style tool, with nine statements for the student to complete.29 The CSACD is copyrighted, and permission to use this instrument was obtained. The original form had been tested for validity and reliability.29 This tool was not revised from its original form and content. However, the researchers applied it to a different health care profession. By making this change in application, the documented validity and reliability may not be as accurate in this research. Thannhauser, Russell-Mayhews and Scott30 reviewed instruments that are available for use in quantitative research that measured different aspects of IPE. The IEPS was rated as good and did not lack sufficient theoretical and psychometric development.

Demographic characteristics on the pre-course survey were summarized. For the items about the roles of registered nurses and pharmacists, both to their own profession’s role and to the other profession’s role in pain relief, categories were collapsed into strongly agreed vs other based on the data distribution. We compared the percent who strongly agreed between the pre- and post-course surveys using chi-square tests. IEPS overall scores and subscores and CSACD scores were summarized and compared between pre- and post-course, overall, and for each student type, using two-tailed t-tests. Post scores also were compared between 2013 and 2014 using two-tailed t-tests. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when p<.05. Analysis was carried out in Stata 13.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The sample consisted of 60 students who completed the survey on the first day of class – 15 nursing and 16 pharmacy students from the spring 2013 course, and 20 nursing and nine pharmacy students from the spring 2014 course. Fifty-five students (90%) completed the survey on the last day of class.

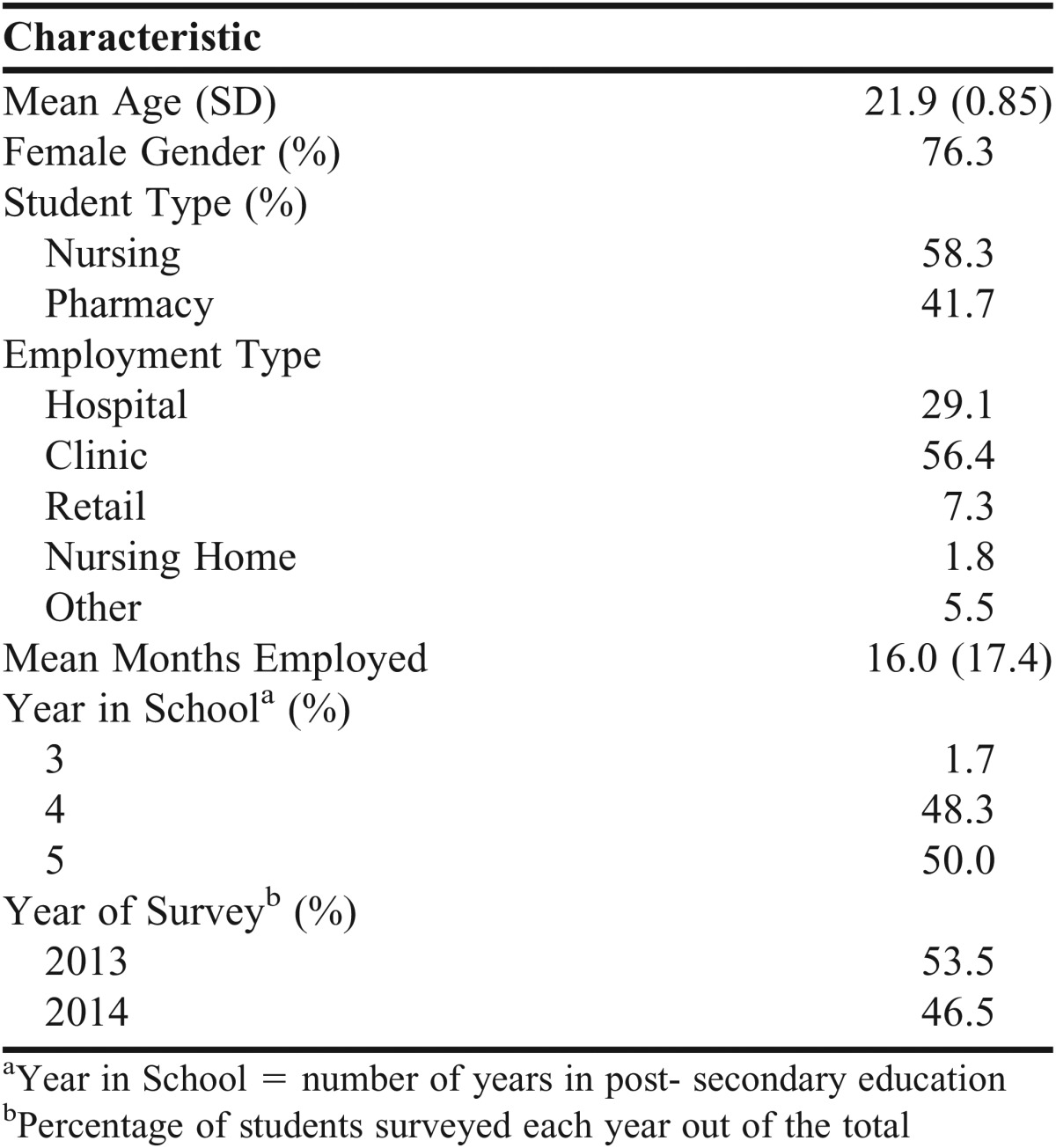

The mean age of students who participated was 21.9, 76% were women, 58% were nursing students, and 42% were pharmacy students. The majority worked in a clinic (56%) or hospital (29%) and had worked for an average of 16 months. All but one student was in the fourth or fifth year of school (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics Table (n=60)

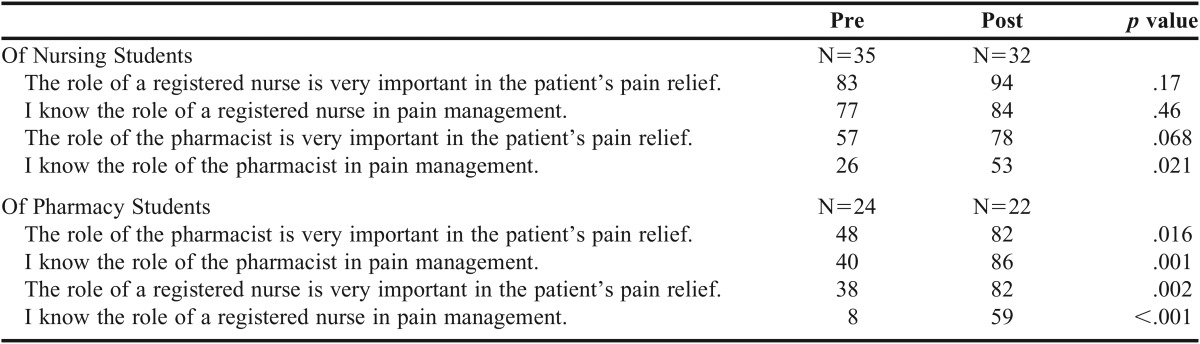

Of nursing students, the percent who strongly agreed with the four statements about the roles of registered nurses and pharmacists being important and knowing the roles increased from pre- to post-course for all four statements, but the difference was only statistically significant for “I know the role of a pharmacist in pain management” (26% pre-course to 53% post-course survey, p=.021). For pharmacy students, the percent who strongly agreed increased statistically significant from pre- to post-course for all four statements (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percent Who Strongly Agree With Statements about Roles

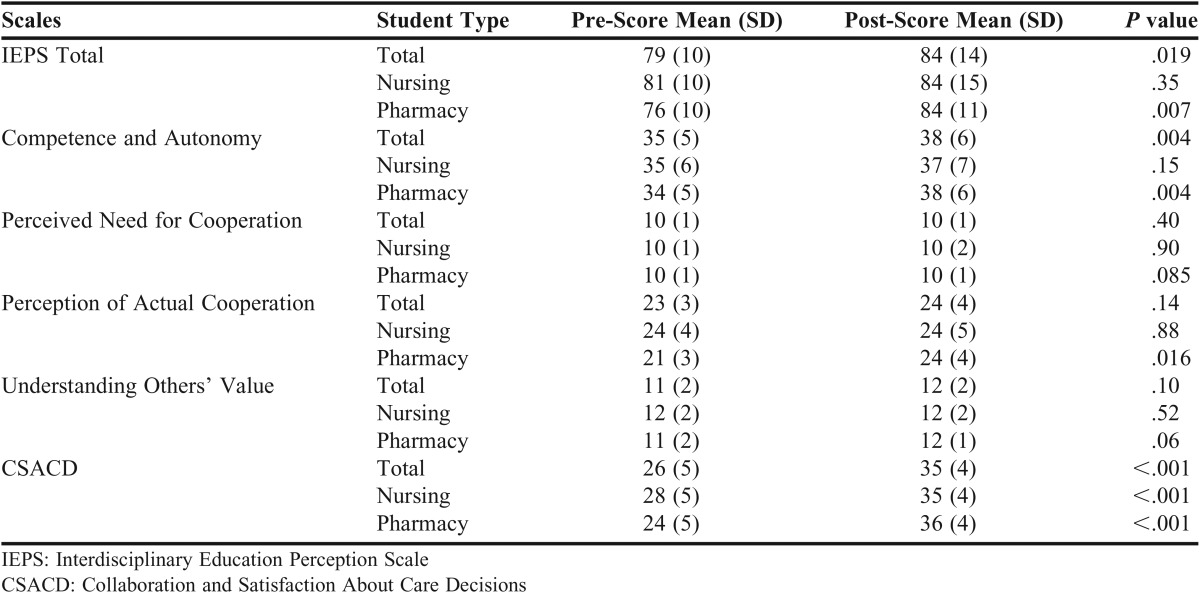

Overall, mean scores were higher in the post-course surveys compared to the pre-course surveys for IEPS total (mean = 84 vs 79, p=.019), IEPS subscore competence and autonomy (mean = 38 vs 35, p=.004), and CSACD (mean = 35 vs 26, p<.001). For nursing students, scores were statistically significantly higher in the post period for CSACD only (35 vs 28, p<.001). For pharmacy students, scores were statistically significantly higher in the post period for IEPS total (84 vs 76, p=.007), IEPS subscore competence and autonomy (38 vs 34, p=.004), IEPS subscore perception of actual cooperation (24 vs 21, p=.016), and CSACD (36 vs 24, p<.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pre- and Post-Scores, Overall and by Type of Student

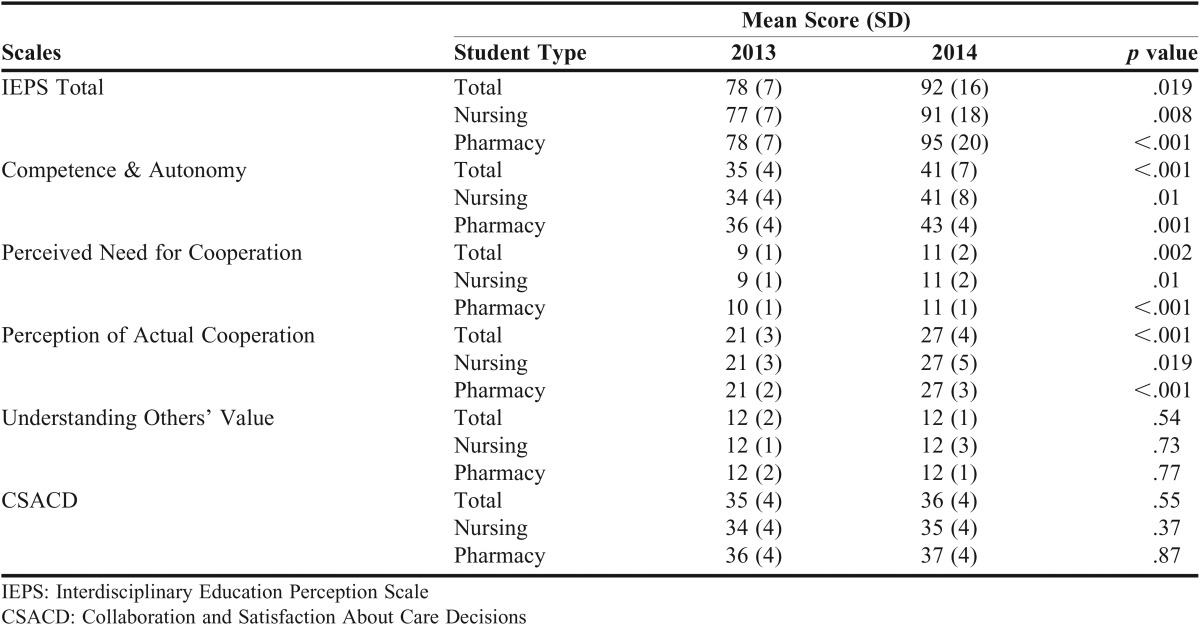

Comparing post scores between 2013 and 2014, scores were higher in 2014 compared to 2013 for: mean IEPS total (92 vs 78, p=.019); IEPS competence and autonomy (41 vs 35, p<.001); IEPS perceived need for cooperation (11 vs 9, p=.002); and perception of actual cooperation (27 vs 21, p<.001). Mean scores for the CSACD were similar between 2013 and 2014. When stratified by student type, the pattern is similar for nursing and pharmacy students (Table 4).

Table 4.

Post Scores, by Year, Overall and by Type of Student

DISCUSSION

This study found that an IPE course for nursing and pharmacy students has significantly increased their knowledge and understanding of the importance of the other profession’s role, and for pharmacy students, the knowledge and importance of their own role in the treatment of pain. Findings from the analysis of four statements about the roles and importance of the roles of nursing and pharmacy professions in the treatment of pain demonstrated that nursing students strongly agreed with the statement that the role of a nurse is very important in the relief of patient pain, as well as a statement of knowledge of their role as a nurse in pain management. The change in the percentage of nursing students who strongly agreed to these statements at the end of the semester was not significant, despite the increased percentage of nursing students who strongly agreed to both statements. We expected nursing students, as spring semester seniors, to have entered the course with knowledge of their role and understanding of the importance of their role as nurses in pain management. We did not expect to see a significant change in their agreement with these statements at the end of the course and none was observed for nursing students.

However, a significant increase was observed between pre- and post-course responses of nursing students who strongly agreed with a statement acknowledging their knowledge of the role of the pharmacist in pain management. This significant increase observed with nursing students leads us to conclude that the IPE course increased their knowledge of the role of pharmacists. Fifty-seven percent of nursing students strongly agreed with the statement that the role of the pharmacist is very important in the treatment of patient pain on the first day of class, although the post-course increase was not significant. This lack of statistical significance could be due to a small number of student participants in the study rather than the lack of real difference. This difference may be attributed to the exposure of senior nursing students to the outcomes of the interventions of pharmacists in patient care during clinical experiences previous to this course. This exposure to the work of pharmacists may have led to a higher percentage of nursing students who strongly agreed with the importance of the role of pharmacists in pain management as they entered the course, although fewer strongly agreed to knowledge of the role of the pharmacist at that point, leaving space for the significant percentage increase observed.

A significant increase in the percentage of pharmacy students who strongly agreed with statements about their knowledge of the nurses’ role and importance in the treatment of patient pain was seen. We think lower than expected pre-course percentages were due in part to the curricular timing of this course and of clinical experiences in the pharmacy program and, therefore, exposure to the work and roles of nurses. The greatest concentration of pharmacy experiential education is included in the curriculum in the semester after this course. Without this experience prior to the course, we would expect the pre-course scores to be low, with room to increase significantly. And, the possibility exists that the low and very low pre-course percentage scores may represent a misconception of health care profession hierarchy in students without exposure to the contributions of other professions in a team. The combination of low pharmacy student pre-course percentages and the IPE course experience leads us to conclude that the significant increase in the percentage of students who strongly agree with knowledge of both the roles and importance of nurses represents a meaningful acquisition of knowledge and appreciation of the other profession.

The data also reveal a significant increase in the percentage of pharmacy students who strongly agree with a statement that acknowledges the importance of their role (p=.016) and knowledge of their role (p=.001) in the treatment of patient pain. Recognizing that the bulk of the experiential learning for pharmacy students has not been employed at this point in their program, we may expect them to have an underdeveloped knowledge of roles and importance of their profession. Additionally, the focus of the pharmacy school program, prior to experiential education may be considered to be the provision of knowledge and skills necessary for the experiential component housed in the year after this course and not necessarily in developing an understanding of roles or their importance, which is featured during the experiential phase of the program. This was most certainly an unexpected finding for pharmacy students in the spring of their fifth year and a matter to consider for further study.

Although statistically significant, the nursing students who strongly agreed to knowledge of the role of the pharmacist in pain management at the end of the course is still rather low at 53%, similarly with pharmacy students who strongly agreed to knowledge of the role of the nurse in pain management at 59%. Perhaps this finding presents an area for course improvement.

The CSACD tool had statements regarding nursing and pharmacy students working together to produce good patient outcomes. Scores for this tool statistically significantly improved from the pre-course and post-course scores overall and for both professions (Table 3). Both nursing and pharmacy students worked together for the simulation patients’ best outcome. The CSACD also allows measurement of the association between the collaboration with the providers and patient outcomes. The researchers feel that better patient outcomes are a goal of IPE. This class increased the collaboration between pharmacy and nursing students, thus improving patient outcomes.

In advanced IPE, the use of simulation for clinical situations/cases is the premier method of instruction for IPE.11 Utilizing four high-fidelity simulations in this IPE pain course increased the CSACD scores of the students in their collaboration and teamwork, ensuring the best patient outcomes. Critical to the production of these positive outcomes was clear interprofessional communication between the nursing and pharmacy students and a depth of understanding of the roles of each profession. Additionally, we speculate that student teams provided positive patient outcomes because of the student realization that they alone did not have to fill every role in patient care and that other professions provide care, reinforcement, and support.

The IEPS scores can be subdivided into four attitude subscales: professional competency and autonomy; perceived need for professional cooperation; perception of actual cooperation and resource sharing within and across professions; and understanding the value and contributions of other professionals/professions. The increase in the IEPS score overall and with the pharmacy students is difficult to interpret. The IEPS score looks at the individual’s profession and has the student rate their profession when comparing it to other health professionals, working with other health professionals, and those who are willing to share information with other health professions.

One explanation as to why the nursing students’ IEPS scores did not improve to a statistically significant number is that their pre-course IEPS started out high to begin with, leaving little room for improvement. Perhaps the nursing students, who were in their last semester of the BSN program, already had high expectations of their profession as they were finishing their college education. The pharmacy students were in their fifth year of a six-year program and had just started their clinical experiences, thus starting out with a lower IEPS score at the beginning of the semester and increasing their IEPS scores at the end of the semester. The nursing and pharmacy students had identical IEPS scores (84) after the completion of the IPE pain course.

The subscores for the IEPS for competency and autonomy, and perception of actual cooperation, were statistically significant for the pharmacy students from the pre- and post-course scores. Additionally, the total IEPS score for the competency and autonomy subscale also was statistically significant. Because of the small sample size and the majority of the students being female, the researchers did not compare the IEPS scores between male and female students, as other research has found that women score higher on the IEPS.31

Post-scores (Table 4) improved in the IEPS from the 2013 to the 2014 class. The statistically significant differences were with the total IEPS score for both the nursing and pharmacy students along with all of the IEPS subscores except for understanding others’ value. The interdisciplinary care plan assignment did not change from 2013 to 2014. We surmise that the addition of three more interprofessional simulations in the spring 2014 class was responsible for this improvement. Current research demonstrates that students have more positive attitudes about IPE after simulation.32 Findings from this research suggest that pre-licensure nursing and pharmacy students are ready to participate in IPE through exposure to an experiential format such as HFSM simulation. The simulations enhanced communication, cooperation, collaboration, and appreciation for the other profession as evidenced by the higher IEPS scores.

The results of this study provide a stimulus and direction to refocus and refine this course. In the past two years since the study was conducted, 2015 and 2016, we have focused on increasing the development of the core IPE competencies and interprofessional team skills and have decreased the focus of the course on the provision of content and knowledge of pain anatomy and physiology, essentially a shift from pain knowledge to an IPE skill focus. To accomplish this, we have asked the presenters in the course to focus on case studies as a method for application of previously acquired knowledge to skill-building. We also have refined the interprofessional care plans and simulations and have asked students to write a personal reflection statement for the course. The researchers have found the student course reflections to be enlightening, both from the perspective of course presenter and simulation strengths as well as from honest and heartfelt discussions of weaknesses in the advertised course description and student behavioral superiority based on profession. These provide the researchers with areas in which to seek continued refinement.

Although this study yielded significant findings for this IPE pain course with nursing and pharmacy students, it nonetheless has limitations. One is the variation in the number of simulations between the spring 2013 and spring 2014 course. The spring 2013 course had only one simulation experience, while the spring 2014 course had four simulations. The reason for the increase in the number of simulations was the positive feedback from students in the spring 2013 course about the one simulation and how beneficial it was.

There is a bias in the self-selective nature of a “pain” elective, especially an elective with the title of Etiology, Assessment, and Treatment of Pain for the Health Care Professional. Those pharmacy and nursing students interested in a pain elective and one that is advertised as an interprofessional course certainly have a selection bias. Additionally, the school of nursing does not have a course specifically addressing pain management of the patient. This material is covered in a fundamentals course and in the courses that address specific populations (ie, Pediatrics, Adult Health, Care of the Critically Ill Patient, Gerontology, etc). Whereas, the pharmacy curriculum includes a biomedical science and therapeutics course in the spring of the second professional year that focuses on pain, muscular skeletal and connective tissue disorders. Third professional year pharmacy students in this course and nursing seniors have completed the curricular coursework prior to the semester that this IPE course is offered.

Another limitation in the study was the use of the convenience sample for the study. A convenience sample makes the recruitment of students easier, but also results in a reduced student sample representation. Therefore, students who volunteer to participate may bias results in doing so. It would have been ideal to have a control group that did not have any interprofessional assignments or simulations. A future study design could include these elements. We believe that similar institutions attempting to incorporate IPEC competencies into their curriculum could benefit from this study by replicating some of the components of this course (simulations as one example) despite the limited class size and non-random sample in this study.

CONCLUSION

The study findings provide evidence that an interprofessional pain course for nursing and pharmacy students, taught by different health professionals, with assignments including interprofessional care plans and simulations and a personal reflection, helps to foster and build upon the Interprofessional Education Collaborative Panel’s competencies for IPE. Nursing and pharmacy students significantly increased their knowledge of the role of the other profession. Pharmacy students alone increased their knowledge and importance of their own role as well as the importance of the role of nurses in pain relief through this course. All students advanced in competency and autonomy measures, but gains in the perception of actual cooperation increased only for the pharmacy students. The quality of interaction and process satisfaction in making care decisions was enhanced for all students. The perceived need for cooperation and understanding of others’ values did not significantly grow for either group of students. As research on IPE is increasing, we believe this single class can spark enhanced interest in IPE courses, assignments that help meet the competencies of IPE, and an increased appetite to raise IPE to a curricular priority through strategic and programmatic inclusion into health care education.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their appreciation to Dr. J. Baggs for allowing them to use her CSACD tool for this IPE research.

Appendix 1. Interprofessional Care Plan

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith KM, Scott DR, Barner JC, DeHart RM, Scott JD, Martin SJ. Interprofessional education in six US colleges of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):Article 61. doi: 10.5688/aj730461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (2016) Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2017.

- 3.World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Health Professions Networks Nursing and Midwifery Office, Department of Human Resources for Health 2010. https://scholar.harvard.edu/hoffman/files/18-jah_ overview_of_who_framework_for_action_on_ipe_and_cp_2010_gilbert-yan-hoffman.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2017.

- 4. Institute of Medicine. Preventing Medication Errors. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2007.

- 5. Greiner A, Knevel E. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality: A Report of the Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed]

- 6.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376(9756):1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;23(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilbert H, Yan J, Hoffman S. A WHO Report: framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. J Allied Health. 2010;39(Suppl 1):196–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurpinski K, Johnson T, Kumar S, Desai T, Li S. Mastering transitional medicine: interdisciplinary education for a new generation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(218):1–3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korner M, Wirtz MA, Bengel J, Goritz AS. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in interprofessional teams. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:243. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0888-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011.

- 12.Lash D, Barnett M, Parekh N, Shieh A, Louie M, Tang T. Perceived benefits and challenges of interprofessional education based on a multidisciplinary faculty member survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):Article 180. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7810180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomasik J, Fleming C. Lessons from the field: promising interprofessional collaboration practices. CFAR, Inc. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2015.

- 14.Bankston K, Glazer G. Legislative: interprofessional collaboration: what’s taking so long? Online J Issues Nurs. 2013;19(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buring S, Bhushan A, Brazeau G, Conway S, Hansen L, Westberg S. Keys to successful implementation of interprofessional education: learning location, faculty development, and curricular themes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):Article 60. doi: 10.5688/aj730460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cranford JS, Bates T. Infusing interprofessional education into the nursing curriculum. Nurs Educ. 2015;40(1):16–20. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolesta S, Chmil JV. Interprofessional education among student health professionals using human patient simulation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(5):Article 94. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wamsley M, Staves J, Kroon L, et al. The impact of an interprofessional standardized patient exercise on attitudes toward working in interprofessional teams. J Interprof Care. 2012;26(1):28–35. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2011.628425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor D, Yuen S, Hunt L, Emond A. An interprofessional pediatric prescribing workshop. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(6):Article 111. doi: 10.5688/ajpe766111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonnell CP, Rege SV, Misto K, Dollase R, George P. An introductory interprofessional exercise for healthcare students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(8):Article 154. doi: 10.5688/ajpe768154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodehorst TK, Wilhelm SL, Jensen L. Use of interdisciplinary simulation to understand perceptions of team members’ roles. J Prof Nurs. 2005;21(3):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soklaridis S, Oandasan I, Kimpton S. Family health teams: can health professional learn to work together? Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(7):1198–1199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neville CC, Petro R, Mitchell GK, Brady S. Team decision making: design, implementation and evaluation of an interprofessional education activity for undergraduate health sciences students. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(6):523–525. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.784731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes D, Carpenter J, Dickinson C. Interprofessional education for community mental health: attitudes to community care and professional stereotypes. Soc Work Educ. 2000;19(6):565–583. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans JL, Henderson A, Johnson NW. Interprofessional learning enhances knowledge of roles but is less able to shift attitudes: a case study from dental education. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16(4):239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2012.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlisle C, Cooper H, Watkins C. “Do none of you talk to each other?”: the challenges facing the implementation of interprofessional education. Med Teach. 2004;26(6):545–552. doi: 10.1080/61421590410001711616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Byrne A, Pettigrew C. Knowledge and attitudes of allied health professional students regarding the stroke rehabilitation team and the role of the speech and language therapist. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2010;45(4):510–521. doi: 10.3109/13682820903222791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luecht RM, Madsen MK, Taugher MP, Petterson BJ. Assessing professional perceptions: design and validation of an interdisciplinary education perception scale. J Allied Health. 1990;19(2):181–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baggs JG. Development of an instrument to measure collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20(1):176–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20010176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thannhauser J, Russell-Mayhew S, Scott C. Measures of interprofessional education and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(4):336–349. doi: 10.3109/13561820903442903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong RL, Fahs DB, Talwalkar JS, et al. A longitudinal study of health professional students’ attitudes towards interprofessional education at an American university. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(2):191–200. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1121215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossier KL, Kimble LP. Capturing readiness to learn and collaboration as explored with an interprofessional simulation scenario: a mixed-methods research study. Nurs Educ Today. 2016;36(1):348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]