Abstract

Objective. To determine the impact of student or faculty facilitation on student self-assessed attitudes, confidence, and competence in motivational interviewing (MI) skills; actual competence; and evaluation of facilitator performance.

Methods. Second-year pharmacy (P2) students were randomly assigned to a student or faculty facilitator for a four-hour, small-group practice of MI skills. MI skills were assessed in a simulated patient encounter with the mMITI (modified Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity) tool. Students completed a pre-post, 6-point, Likert-type assessment addressing the research objectives. Differences were assessed using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Results. Student (N=44) post-test attitudes, confidence, perceived or actual competence, and evaluations of facilitator performance were not different for faculty- and student-facilitated groups.

Conclusion. Using pharmacy students as small-group facilitators did not affect student performance and were viewed as equally favorable. Using pharmacy students as facilitators can lessen faculty workload and provide an outlet for students to develop communication and facilitation skills that will be needed in future practice.

Keywords: motivational interviewing, facilitation, attitudes, skills, confidence

INTRODUCTION

Patient-centered communication strategies are becoming increasingly important for pharmacists as the profession shifts to a more clinical role.1 With this increasing emphasis on clinical pharmacy, schools of pharmacy are seeking to prepare their students to better communicate with patients. The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) and the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) have recognized the need to educate pharmacy students in effective patient communication skills.2 For example, in the 2013 CAPE educational outcomes, Standard 3.6.1 focuses on being able to communicate effectively with patients in a manner that empowers the patient to take control of their health.

One method that has shown efficacy in promoting positive health behaviors is motivational interviewing (MI).3-5 Originating in chemical dependency counseling, MI is a patient-centered style of counseling that seeks to have the patient talk himself or herself into a change.5 This is done through eliciting change talk from the patient and accessing the patient’s motivation for making the change.5,6 Four key components comprise all MI techniques: expressing empathy, rolling with resistance, supporting self-efficacy, and developing discrepancy.5 Overall, MI interactions are collaborative in nature and seek to honor the patient’s autonomy.6 MI has been shown to be effective in promoting positive health behaviors (ie, weight reduction, blood pressure control, antiretroviral regimen adherence) and reducing maladaptive health behaviors (ie, chemical dependency).3,4,6

Not only has MI been shown effective in promoting positive health behaviors, but within health care education, MI has been shown to increase student confidence and their ability to engage in health behavior change counseling in multiple health care professions.7,8 It also has been demonstrated effective at increasing student counseling abilities specifically within pharmacy education.2,9 Based on the efficacy of MI in both patient encounters and student confidence, it is important to educate pharmacy students in this communication method. A variety of methods have been used to incorporate MI into the curriculum. Medical and pharmacy schools have used various pedagogies to teach MI principles and techniques, including lecture, interactive class activities, student role playing, and simulated patients.7,8,10,11 Within curricular design, pharmacy schools have implemented MI education either as an elective or as a longitudinal exercise throughout the first three years of pharmacy school.2,9

When training students to use MI skills, it is not known whether student or faculty small-group facilitators are equally effective in training students on MI skills. The purpose of this project is to compare the efficacy of student and faculty small-group facilitators in achieving the desired outcomes. If students are equally effective, this will reduce faculty burden associated with MI education while providing additional educational and leadership opportunities for student facilitators. Student facilitators would not only be strengthening their MI skills during this process but also would be modeling leadership to cohorts behind them.12

The purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy of faculty and student small group facilitators by examining changes in student attitude toward MI, confidence in using MI techniques, perceived competence in MI skills, and measured competence in using MI techniques after educational sessions led by faculty or students.

METHODS

This study utilized a randomized pre-test/post-test/retrospective group design to compare the efficacy of facilitator type in MI education. This study was approved under exempt status by the Institutional Review Board at Cedarville University.

In May 2013, all pharmacy faculty members and several pharmacy students working on summer research projects participated in a two-day MI training seminar. Four P3 students and four faculty members were selected out of that seminar to participate as facilitators for the project. (All faculty facilitators and two of the student facilitators also were involved in the design and execution of this study.) All student and faculty facilitators attended an additional two-hour facilitator training session before the first educational session. During the training session, facilitators received a review of MI techniques, learned teaching strategies for MI sessions, and role-played facilitating small groups. The sessions were highly interactive, offering the facilitators opportunities to practice MI skills via a variety of exercises. Then, facilitators were assigned to groups via a random number generator.

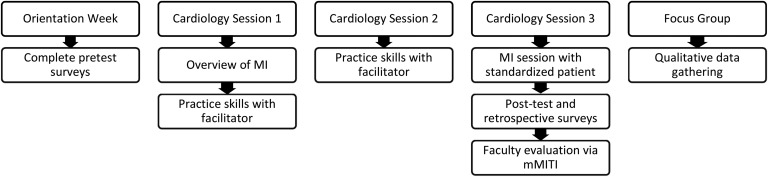

Study participants consisted of second professional year pharmacy students (P2). Since the school of pharmacy utilizes a team-based learning pedagogy, P2 students already were allocated into eight small groups of five to six students, as outlined previously.13 A timeline summary of the study and sessions is provided in Figure 1. In their P1 year, students had a two-week introduction to MI during their self-care course and their pharmacy practice lab, where they learned the principles of MI and practiced the skills with one another. Since MI is useful when addressing health behavior changes needed for cardiovascular diagnoses, MI was incorporated into the cardiology therapeutics module in the fall of 2014. In the module, P2 participants engaged in three MI education sessions (cardiology sessions 1-3). During the first session, a very brief review of MI and patient communication was given, and students were subsequently broken up into their assigned groups with their facilitator for the remainder of the session as well as the second session.

Figure 1.

Overview of Motivational Interviewing Sessions and Timing of Assessments.

During these sessions, facilitators began with patient statements of resistance, frustration or defeat and having students create a one to three sentence response that was MI consistent. Students then shared their responses and discussed the variety of potential responses to each statement. Next, patient cases were utilized to practice using MI techniques in a simulated scenario. One student was asked to serve as a patient and the other as a pharmacist, with the remaining students observing and providing feedback post-scenario. The pharmacist case contained basic information about the patient and relevant lab values, while the patient case contained additional information regarding lifestyle choices and the patient’s readiness for change. The student playing the role of pharmacist was given three to five minutes to engage the student playing the role of patient using MI. At the end of the interview, students were asked to provide peer feedback on the use of MI techniques and skills. After the students had exhausted their feedback, the facilitator would add any additional comments or observations they had.

The third session was used as an evaluation session, providing the students with the opportunity to utilize MI skills with a simulated patient. Four actors were hired, trained as standardized patients, and given information regarding their health problems, medications, lifestyle barriers to change, and overall attitude. Each patient was given the same information, so each student encountered the same case.

Each student had five minutes to view the patient case before interviewing the patient, then they entered the room and discussed health behavior changes with the patient using MI techniques. Students had up to five minutes with the patient before being told to stop. Encounters were video-recorded for later assessment. Upon completion of the interview, the students were taken to a sequestering area where they completed the post-test and retrospective survey and waited until all students had completed the exercise.

All P2 student participants were invited to complete assessments of their attitude, confidence, and perceived competence during school of pharmacy orientation week (pre-test) and immediately after the completion of their video interview (post-test and retrospective pre-test) using survey instruments, which were later de-identified for analysis. The assessment instruments were designed based on instruments previously used by the school of pharmacy, as well as instruments described in the literature.9,14 All instruments underwent peer and expert review before administration. A 6-point Likert-type scale was used in a forced-choice style that eliminates the “neutral” option. This has been reported to be common practice and is based on the critique of neutral items as non-differentiating items with a lack of ability to distinguish between the truly neutral and ambivalent respondent.15,16

Student attitude toward motivational interviewing was assessed via four questions gauging a student’s interest in learning about MI, plans to use MI in the future, and the usefulness of MI.9 The attitude Likert scale was anchored with 1 as “strongly disagree” and 6 as “strongly agree.” Student confidence was assessed via two mini-cases that provided a patient situation and asked students to rate their confidence in using MI techniques to motivate the patient to change,8 and 16 questions that asked students to rate their confidence in performing certain MI macro- and micro-skills.9,14 These items also utilized a Likert scale, anchored with 1 as “very unconfident” and 6 as “very confident.” Perceived competence items were created by asking students their degree of agreement with statements regarding the ease or difficulty in performing a variety of MI macro and micro-skills. The list of skills was created by extrapolating the skills assessed by the mMITI into the series of items.9 These items used a Likert scale of 1 as “strongly disagree” and 6 as “strongly agree,” and alternated between positive and negative statements.

There were a few items that differed between the assessments. In the pre-test survey, three demographic questions were asked to determine gender, age, and ethnicity of participants. The retrospective test was designed in such a way that students were asked to assess each survey item according to their attitude, confidence, or competence prior the MI educational sessions. The post-test also included a 12-item assessment that asked students to evaluate their facilitator’s abilities in areas such as communication, MI knowledge, effectiveness in teaching, time management during the sessions, organization, patience, friendliness, helpfulness, respect for students, enthusiasm, usefulness of feedback, and overall performance. These items also included a 6-point Likert-type scale, with 1 corresponding to “extremely poor” and 6 corresponding to “excellent.”

Video recordings of each P2 student interview were distributed to six faculty members and two P3 research assistants (all who received additional training on evaluating the videos) who assessed the recordings for measured competence in MI skills using the modified Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity tool (mMITI) by Buring9 and colleagues. No individual reviewed the videos of students they facilitated. The mMITI evaluates MI practitioners in four domains. Two global scores, assessed on a Likert scale of 1-7, assess the practitioner’s ability to demonstrate “empathy/understanding,” and the overall “spirit of MI” displayed in the interaction. The other two domains of the mMITI focus on behavior counts. The first, “MI adherent behavior,” asks assessors to tally the number of MI adherent behaviors and the number of MI non-adherent behaviors displayed in the interaction, and calculate the percentage of behaviors tallied that were MI adherent. Based on this percentage, a section sub-score (out of eight total possible points) is assigned. The “open-ended questions” domain asks assessors to tally the number of open-ended questions and closed-ended questions, and similar to MI adherent behavior, calculate the percentage of open-ended questions and assign the appropriate sub-score (out of eight total possible points) for this category. Each of the four domains is added together to comprise the practitioner’s total mMITI score. Higher scores indicate better use of MI skills, and the highest possible total score is a 30.9

To determine the utility of the MI sessions and ways to improve the sessions, 10 P2 students were randomly selected and invited to participate in a two-hour focus group session. Invited participants represented students who had student and faculty facilitators. Questions for the focus group were created out of the study objectives. The same two student research assistants who participated in the design of the project and evaluated videos were trained in focus group research and facilitated the session. The session was audio-recorded using LiveScribe pens, and additional notes were taken by the facilitators. A de-identified transcript of the session was created verbatim from the notes and audio recording and used for further analysis.

Statistical analysis of survey and mMITI data was performed in SPSS v 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Data were checked for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Since the data violated the assumption of normality, nonparametric tests were used for analysis. Based on the categorical nature of data, medians of each item are reported. Responses to each survey type were compared based on facilitator type (student or faculty) with the Mann-Whitney-U test. Scores on the mMITI were compared based on the type of facilitator with the Mann-Whitney-U test. Content analysis was performed by two researchers in QSR NVivo 10 (Burlington, MA) on the focus group transcript using grounded theory to reveal common themes among responses.17,18

RESULTS

Demographic data on the study population are shown in Table 1. For the participants (N=44, 100% response rate), student attitude, confidence, and perceived competence measures are shown in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences between P2 student participants who had student or faculty member facilitators, with the exception of the pre-test evaluation of perceived competence in asking close-ended questions. Student-facilitated participants reported it was more difficult to avoid asking close-ended questions than the faculty-facilitated participants.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Information (N=44)

Table 2.

Comparison of Student Attitudes, Confidence, and Perceived Competence by Facilitator Group

The comparison of mMITI results between the two study groups is shown in Table 3. Again, there were no statistically significant differences in measured competence by facilitator type. Finally, the results of facilitator evaluations are shown in Table 4. While student facilitators were ranked slightly lower on the overall rating and organization, there were no statistically significant differences between student and faculty member facilitators.

Table 3.

Comparison of Student mMITIa (measured competence) Scores by Facilitator Group

Table 4.

Comparison of Facilitator Evaluations

During the focus group session, students with both faculty and student facilitators commented that faculty facilitators had good “real world” knowledge, but could be more intimidating and less relatable than student facilitators. The P2 students felt more comfortable with student facilitators but reported that some student facilitators had difficulty managing group dynamics, such as drawing out quieter students. However, the focus group indicated that the student facilitators had a good grasp of MI knowledge and techniques, with one student commenting, “Whether or not the student had lots of experience, she at least understood it well and could explain it well, and was confident in the techniques.”

When discussing their overall MI skills, most students expressed that MI felt unnatural to them (78% of focus group), and they were not sure how to utilize MI in every day pharmacy practice (45%): “I feel confident in principles, but…incorporating that into every day speech can be a little difficult,” and “It didn’t seem weird in the context we were doing it as much, because everyone is expecting you to say something like that, but if I were to, like, say those things to an actual patient, I feel like I might get some weird looks.” Students specifically stated that they were not sure how to start an MI encounter with a real patient (44% - “Should I initiate change talk when someone’s buying a bottle of aspirin in the aisle, or should I wait for them to approach me?”), how to use MI skills within the time demands of retail pharmacy practice (22% - “I only talk to a patient for, like, one minute”), and how best to respond to a resistant patient (22% - “I know you have to ‘roll with resistance,’ and all that, but what would that look like practically when you have a patient who’s just not willing to quit, or take their medication, or…”).

DISCUSSION

Students who had either faculty or student facilitators for learning and practicing MI skills had equivalent attitudes, confidence, perceived competence and measured competence at study completion. A review of tutoring-related research concurs, finding that peer tutoring was typically equivalent or more effective than faculty tutoring.19 Further, attitudes, confidence, and perceived competence were overall positive at the post-test (median scores of 4 out of 6 or higher), and measured competence was considered a passing score (22/30 and 24/30). Confidence, as well as mean scores (measured by the mMITI), were similar at other institutions after incorporating MI training in their curriculum.9

While students could certainly improve in their competence, the incorporation of these activities provided students an additional opportunity to practice their MI-related communication skills. Students must be prepared to communicate appropriately as part of interprofessional teams and with patients, according to the 2016 ACPE standards. MI is an important communication method for students to learn, as it promotes student engagement in health behavior change counseling and overall counseling abilities.2,3,7-9 Additionally, it is effective in assisting patients in making health behavior changes.3,4,6

Student evaluations of their facilitators also suggested equivalence and, thus, may be utilized to reduce faculty workload associated with active learning. Active learning, such as small group practice of skills, is important for students to apply knowledge and skills before practice. In Standard 10, ACPE encourages incorporation of active learning in the classroom20, and at least 87% of faculty use active learning in their courses according to a recent survey.21 However, active learning results in greater faculty workload.21 Because workload responsibilities for practice department faculty have grown, this has resulted in less time for scholarship due to clinical teaching, didactic teaching (active learning pedagogy), and service responsibilities.22,23 By incorporating student facilitators when appropriate, faculty members may have increased time to spend in other academic exercises, such as service, preparation of active learning exercises, or scholarship activities. This involvement can lead to personal, school, and academic pharmacy benefits.

Additionally, student facilitators may provide benefits to those facilitating. Upon graduation, newly licensed pharmacists can quickly enter precepting roles or co-precepting roles. Without prior practice, learning how to give feedback effectively can be challenging. Preceptors often function more effectively when given training on evaluating students.24,25 Not all pharmacists receive training programs, and building these skills while in pharmacy school may be beneficial. For example, in problem-based learning (PBL), the peer-assessment process where students give feedback and grade teammates’ presentations improved student confidence as well as self-directed learning skills.26 Others also have included peer-to-peer learning in experiential education and found improved skills vs traditional models of learning,27 and recently, interprofessional peer teaching effectively improved knowledge on ambulatory devices.28

In addition to similar efficacy between faculty and student facilitators, the focus groups provided some interesting information. While students were more comfortable with student facilitators, faculty were better at the process of facilitating. Because faculty had completed a residency or other post-graduate training and had experience facilitating groups, it is understandable that students may not have been as effective at facilitating. For example, these skills often are obtained in the residency setting, as residencies often include a teaching certificate program or opportunities that may include training and practice in facilitating small groups.29,30 Thus, while students did undergo training in this experience, further practice and engagement in facilitation may be needed to produce effective small group interactions. Additionally, faculty members participating in this project also had “real life” experience as health care professionals; thus, they could discuss using motivational interviewing in patient encounters with their groups, which provided greater context. These are some of the inherent limitations to using students as facilitators. In future studies, an in-depth training seminar in small group facilitation could be incorporated to improve skills. Further incorporation of MI skills into Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences (IPPEs) or co-curricular activities also could provide more “real-world” examples that students can draw from when facilitating.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size of students was small, limiting the generalizability of the results to similar institutions and may have lacked sufficient power to determine significant changes. Second, while the mMITI instrument has been utilized in pharmacy education research,9 it has not yet undergone validation testing. Additionally, within the survey instrument, many median scores fell in the upper range of the scale. This could indicate that social desirability bias influenced student responses to the survey, or could reflect inflated self-assessment of skills within the surveyed students. Within the focus group, there was an over-representation of participants with student facilitators, despite random sampling of focus group participants. Thus, the opinions of these students may not reflect the opinions of the group. Further, the qualitative data, because it was not the focus of this project, was coded by a single researcher and could have affected the results. Finally, a different study design, such as cross-over, would have strengthened the results.

CONCLUSION

Results from this project suggest that using pharmacy students to facilitate peer-review focused small group sessions can increase student confidence in MI and health behavior change counseling skills, but work is still needed to reinforce the utility of MI in practice. By incorporating opportunities to address communication skills throughout the curriculum31 in addition to the small group sessions added here, students may be able to translate these skills into practice. Using MI small group student facilitators fulfills the ACPE mandate to have students teaching students and may help lessen faculty workload. Further research is needed to assess the impact of facilitation on the student facilitator’s MI outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this study was provided by an internal grant from Cedarville University School of Pharmacy. The authors gratefully acknowledge Jan Kavookjian, PhD, MBA, for teaching the two-day motivational interviewing seminar for Cedarville School of Pharmacy faculty and allowing the use of her learning materials for student training. The authors also acknowledge Jordan Nicholls and Heather Rose for their contributions as student facilitators.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murad MS, Chatterley T, Guirguis LM. A meta-narrative review of recorded patient-pharmacist interactions: exploring biomedical or patient-centered communication? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goggin K, Hawes SM, Duval ER, et al. A motivational interviewing course for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(4):Article 70. doi: 10.5688/aj740470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiIorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, et al. Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: a randomized controlled study. AIDS Care. 2008;20(3):273–283. doi: 10.1080/09540120701593489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rollnick S, Allison J. Motivational interviewing. In: Heather N, Stockwell T, eds. The Essential Handbook of Treatment and Prevention of Alcohol Problems. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2004:105–115.

- 6.Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martino S, Haeseler F, Belitsky R, Pantalon M, Fortin AH. 4th. Teaching brief motivational interviewing to year three medical students. Med Educ. 2007;41(2):160–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poirier MK, Clark MM, Cerhan JH, Pruthi S, Geda YE, Dale LC. Teaching motivational interviewing to first-year medical students to improve counseling skills in health behavior change. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2004;79(3):327–331. doi: 10.4065/79.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buring SM, Brown B, Kim K, Heaton PC. Implementation and evaluation of motivational interviewing in a doctor of pharmacy curriculum. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2011;3(2):78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spollen JJ, Thrush CR, Mui DV, Woods MB, Tariq SG, Hicks E. A randomized controlled trial of behavior change counseling education for medical students. Med Teach. 2010;32(4):e170–e177. doi: 10.3109/01421590903514614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lupu AM, Stewart AL, O’Neil C. Comparison of active-learning strategies for motivational interviewing skills, knowledge, and confidence in first-year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(2):Article 28. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jungnickel PW, Kelley KW, Hammer DP, Haines ST, Marlowe KF. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/aj7308156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frame TR, Cailor SM, Gryka RJ, Chen AM, Kiersma ME, Sheppard L. Student perceptions of team-based learning vs traditional lecture-based learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(4):Article 51. doi: 10.5688/ajpe79451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell K, Cole BA. Improving medical students’ success in promoting health behavior change: a curriculum evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1503–1506. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0678-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen IE, Seaman CA. Likert scales and data analyses. Qua Prog. 2007;40(7):64–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards AL. A critique of ‘neutral’ items in attitude scales constructed by the method of equal appearing intervals. Psychol Rev. 1946;53(3):159–169. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Richards L. Handling Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide. 3rd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2014.

- 18. Taylor B, Francis K. Qualitative Research in The Health Sciences: Methodologies, Methods and Processes. London, England: Routledge; 2013.

- 19.Santee J, Garavalia L. Peer tutoring programs in health professions schools. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):Article 70. doi: 10.5688/aj700370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the profession program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2016.

- 21.Stewart DW, Brown SD, Clavier CW, Wyatt J. Active-learning processes used in US pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 68. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robles J, Youmans SL, Byrd DC, Polk RE. Perceived barriers to scholarship and research among pharmacy practice faculty: survey report from the AACP Scholarship/Research Faculty Development Task Force. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(1):Article 17. doi: 10.5688/aj730117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smesny AL, Williams JS, Brazeau GA, Weber RJ, Matthews HW, Das SK. Barriers to scholarship in dentistry, medicine, nursing, and pharmacy practice faculty. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(5):Article 91. doi: 10.5688/aj710591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assemi M, Corelli RL, Ambrose PJ. Development needs of volunteer pharmacy practice preceptors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(1):Article 10. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerulli J, Briceland LL. A streamlined training program for community pharmacy advanced practice preceptors to enable optimal experiential learning opportunities. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):Article 9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kritikos VS, Woulfe J, Sukkar MB, Saini B. Intergroup peer assessment in problem-based learning tutorials for undergraduate pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(4):Article 73. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindblad AJ, Howorko JM, Cashin RP, Ehlers CJ, Cox CE. Development and evaluation of a student pharmacist clinical teaching unit utilizing peer-assisted learning. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2011;64(6):446–450. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v64i6.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadowski CA, JC-h Li, Pasay D, Jones CA. Interprofessional peer teaching of pharmacy and physical therapy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(10):Article 155. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7910155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gettig JP, Sheehan AH. Perceived value of a pharmacy resident teaching certificate program. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):Article 104. doi: 10.5688/aj7205104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romanelli F, Smith KM, Brandt BF. Teaching residents how to teach: a scholarship of teaching and learning certificate program (STLC) for pharmacy residents. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(2):Article 20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kavookjian J, Berger BA. Using a transtheoretical model approach to teaching patient counseling skills. Am J Pharm Educ. Podium and Poster Abstracts. 2000;64(Winter Supplement 2000):100S–101S. [Google Scholar]