Abstract

Objective. To identify and describe the core competencies and skills considered essential for success of pharmacists in today’s rapidly evolving health care environment.

Methods. Six breakout groups of 15-20 preceptors, pharmacists, and partners engaged in a facilitated discussion about the qualities and characteristics relevant to the success of a pharmacy graduate. Data were analyzed using qualitative methods. Peer-debriefing, multiple coders, and member-checking were used to promote trustworthiness of findings.

Results. Eight overarching themes were identified: critical thinking and problem solving; collaboration across networks and leading by influence; agility and adaptability; initiative and entrepreneurialism; effective oral and written communication; accessing and analyzing information; curiosity and imagination; and self-awareness.

Conclusion. This study is an important step toward understanding how to best prepare pharmacy students for the emerging health care needs of society.

Keywords: collaboration, communication, adaptability, jobs-to-be-done, competencies

INTRODUCTION

The US health care system needs change to improve the quality of care, enhance the patient experience, and reduce health care costs.1 Care is fragmented and poorly coordinated, and interprofessional, team-based care is not where it needs to be to facilitate the delivery of high quality care. Further, a critical component of improving national health care centers is the need to improve the safe and effective use of medications. Numerous calls have emerged for reform in health professions education and highlight ongoing concerns about the ability of current curricula to prepare students for the continual improvement of health and health care.2-6 Employers within and outside health care are increasingly seeking graduates who are able to think critically, work in highly collaborative environments, communicate clearly, ask good questions, and solve complex problems.7 Medicine, nursing, and pharmacy schools are further challenged with educating students amid rapidly expanding information about health and medicines, increasingly complex health care systems, ongoing shifts in legislative and regulatory requirements, and emerging models of care delivery and payment reform. Embedded in this challenge are the evolving roles of health care providers who must effectively respond to these changes and work collaboratively to proactively identify solutions that promote and improve the health and well-being of patients.

Although a growing body of evidence highlights the importance of designing practice models to achieve interprofessional care that is patient-centered and effective, many health care professionals do not fully understand the capabilities of other health care team members and often struggle to effectively capitalize on the expertise and talents of each other.6 The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) identified roles and responsibilities as a core interprofessional collaborative practice competency domain for collaborative practice, proposing that providers “use the knowledge of one’s own role and those of other professions to appropriately assess and address the health care needs of the patients and populations served.”6 Understanding the skills and competencies needed by members of the health care team is critical for ensuring that educational experiences and curricula are structured to prepare aspiring health professionals for contemporary health care challenges. Further, elucidating the skills desired from specific health professions disciplines will facilitate work aimed at optimizing the roles and responsibilities of team members serving to improve patient care.

Across multiple health professions, curriculum accreditation standards are emphasizing interprofessional education (IPE) to better prepare students for the challenges of real world practice. The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), for example, mandates in Standard 7.9 that “the faculty of a medical school ensure that the core curriculum of the medical education program prepares medical students to function collaboratively on health care teams that include health professionals from other disciplines as they provide coordinated services to patients.”8 In addition, the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) details in Standard 11 the need to prepare all “pharmacy students to provide patient-centered care in a variety of practice settings as a contributing member of an interprofessional team with competency in team expectations, education, and practice,” and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) includes “interprofessional communication for improving patient outcomes” as a critical component of undergraduate and graduate accreditation.9,10 The National League for Nursing (NLN) has challenged nurse educators to collaborate with other health professions to develop meaningful interprofessional education and practice opportunities for students as part of undergraduate and graduate learning experiences.11

Meeting the health care needs of society, optimizing team-based care, and developing effective programs that foster interprofessional education and care will require a more rigorous and nuanced understanding of the knowledge, skills, and abilities of graduates emerging from health professions curricula and the job to be done by specific members of the health care team. Literature that describes the qualities and characteristics requisite for success in the various health professions appears largely descriptive and positional in nature. In pharmacy, recent white papers propose core competencies for pharmacy practice. Jungnickel and colleagues, for example, projected future practice competencies in a white paper for the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) that included professionalism, self-directed learning competencies, leadership and advocacy, interprofessional collaboration, and cultural competency.12 In an American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) white paper on clinical pharmacist competencies, Burke and colleagues identified and advocated for clinical problem-solving, judgment, and decision-making; communication and education; medical information evaluation and management; management of patient populations; and therapeutic knowledge.13 The Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) 2013 Educational Outcomes, derived from a literature review and vetted with various stakeholders, included foundational knowledge, essential for practice and care, approach to practice and care, and personal and professional development.14

For many professions, there remains a need for research that examines the contemporary skills associated with 21st century health care. The purpose of this study was to identify and describe the core competencies and skills deemed essential for success of pharmacists in today’s health care system. As described below, this research is framed by Christensen’s jobs-to-be-done theory,15 analyzed according to Tony Wagner’s New World of Work and the Seven Survival Skills16 and presented within the context of interprofessional health care and education. Identifying these qualities provides critical insight into curriculum design and practice innovation for pharmacy and other health professions striving to improve patient care and care delivery.

In his book, Wagner describes a core set of skills identified as necessary for success in today’s workplace.16 These skills, Wagner argues, define a “new and very different kind of worker (p. 41)” and that those without these skills are “unprepared to be active and informed citizens…who will continue to be stimulated by new information and ideas (p. 14).”16 Specifically, the seven survival skills include: critical thinking and problem-solving, which is reflected by asking good questions, dealing with vast amounts of information, deciding what’s accurate and what’s not, and having a plan of action; collaboration across networks and leading by influence, which includes working in teams, making your own decisions, understanding and respecting difference among people, leading and influencing the people around you; agility and adaptability, characterized by working with disruptions, using various tools to solve new problems, ability to work when there isn’t a right answer, and adapting to constant change; initiative and entrepreneurialism, which means being proactive, actively looking for ways to improve systems, courage to try and fail, generating your own answers and solutions; effective oral and written communication, which includes clear and concise writing and speaking, discretion for using different levels of communication, and presentation skills; accessing and analyzing information, which encompasses finding and synthesizing information, using information from a variety of sources, and understanding and responding to how rapidly information is changing; and curiosity and imagination, which is reflected by the ability to continually ask great questions (eg, “What if…?”), dreaming, searching for unique solutions, dissatisfaction with the status quo, and empathy.16,19

METHODS

The University of North Carolina (UNC) Eshelman School of Pharmacy is implementing a redesign of its doctor of pharmacy curriculum using a process called curriculum transformation.17 A hallmark of the curriculum transformation to date has been applying the principles of Clayton Christensen’s jobs-to-be-done theory.15 This theory challenges educational leaders to articulate what it is that graduates will be hired to do. In other words, what is the job to be done by pharmacy graduates in the year 2020 and beyond? Christensen argues that if you do not understand what your products (ie, graduates) should be hired to do, you cannot develop the best product for the market. The idea then is to design a curriculum that facilitates student development toward the endpoint, which aims to promote better understanding of the content or processes that are essential to learning. We believe that this theory is a critical exercise for effectively designing and implementing educational opportunities that enable pharmacy students to develop the skills and competencies necessary for contemporary health care.

To identify the job to be done by pharmacists as integral members of the health care team, we interviewed 103 preceptors, pharmacists, students, and partners assembled for the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy’s Second Annual Preceptor and Partnership Symposium in January 2015, Preparing for Curriculum 2015: Re-engineering Experiential Education. One goal of the symposium was to engage participants in thinking about the job to be done by pharmacists in as much the same way we have engaged our campus-based faculty in this discussion as a part of our curriculum transformation efforts. Specifically, six breakout groups of 15-20 preceptors, pharmacists, and partners engaged in a facilitated discussion about the qualities and characteristics relevant to the success of a pharmacy graduate in today’s health care system (Appendix 1). Each group had a trained facilitator and a note-taker.

All breakout group discussions were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Standard qualitative methods were used to analyze the transcriptions. Two research team members analyzed the data using qualitative content analysis, in which themes and subthemes were identified.18 The first step of analyzing the data included reading and re-reading the transcripts to become familiar with the data. The researchers then used a constant comparative method to code the data according to the categories and subcategories elucidated by Wagner.16

The researchers worked together to compare findings and reach consensus on emerging themes and subthemes. Preliminary reports were presented to additional research team members for peer-debriefing and to participants from the symposium for member-checking. These qualitative research steps (ie, multiple coders, peer-debriefing, member-checking) promote trustworthiness of the findings. The study was reviewed by the UNC Institutional Review Board and was classified as exempt.

RESULTS

One-hundred and three symposium attendees participated in breakout groups with each group composed of participants from various site types, gender, and positions. Fifty-eight participants were from inpatient practice sites (56.3%), 17 from community practice sites (16.5%), 17 from the school (16.5%), and 11 from ambulatory care sites (10.6%). Thirty-six participants were male (35%). Twenty-seven held on-campus or experiential faculty positions (26.2%), 50 served as pharmacy preceptors for students (48.5%), 10 were students (9.7%), seven were residents or postdoctoral fellows (6.8%), and nine were other (eg, hospital administration, school staff) (8.7%).

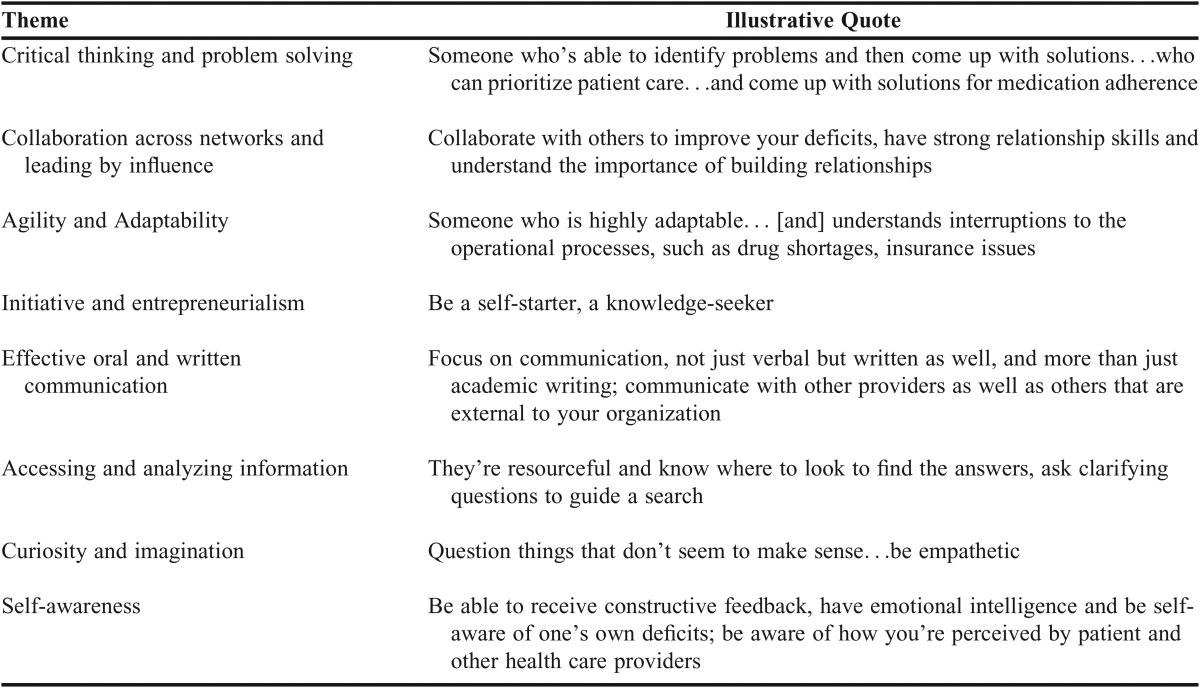

Eight overarching themes were identified from the data. The first seven themes were represented by Wagner’s seven survival skills,16 while the eighth theme emerged inductively: critical thinking and problem-solving; collaboration across networks and leading by influence; agility and adaptability; initiative and entrepreneurialism; effective oral and written communication; accessing and analyzing information; curiosity and imagination; and self-awareness. Table 1 provides illustrative quotes from a composite description of a pharmacy graduate provided by a participant, organized by theme. Additional quotes from various participants are provided in-text, with a collection of quotes also provided in Appendix 2. The pharmacy content associated with these comments focused on medication therapy expertise, patient care optimization, and health care infrastructure.

Table 1.

Illustrative Quotes From a Composite Description Provided by a Participant, Organized by Theme

Critical thinking and problem solving included asking and anticipating good questions, dealing with vast amounts of information (eg, most frequently used drugs, prevalent diseases, managing large groups of patients), prioritizing responsibilities and managing time, and having the ability to differentiate between accurate and inaccurate information. One participant said, “…we have to teach…future graduates what is the right question to ask for us to be able to move forward.”

Participants also identified collaboration and leadership by influence as noteworthy characteristics; specifically, the ability to foster relationships across interdisciplinary teams in both virtual and face-to-face settings and having a sense of accountability, ownership, and responsibility of decisions. Participants mentioned specifics such as working through disagreements and committing to a plan of action.

Theme three, agility and adaptability, encompassed the ability to quickly adapt to constantly changing environments and patient care situations and working with disruptions. The participants emphasized the importance of navigating the multiple roles a pharmacist may serve such as clinician responsible for managing drug therapy, consultant, patient educator, and care coordinator. The participants also commented on the importance of taking initiative and having a spirit of entrepreneurialism, theme four. The participants indicated the pharmacist of 2020 and beyond should be proactive. For example, one participant said that they should “be a self-starter, a knowledge-seeker, a work-seeker.” Additional traits such as serving as an advocate for the profession while actively searching for ways to improve it and having the confidence to try new things and fail also were expressed. Furthermore, as one participant said, future pharmacists should be “proactive within that system to participate in the recognition [of the problem] and the solution.”

The fifth theme, effective oral and written communication skills, includes the ability to communicate clearly and concisely. As one participant said, “Sometimes all you have is an opportunity to do a two-minute elevator pitch…how do you do that?” An additional subtheme highlighted one’s capacity to recognize how and when to use different levels of communication. For example, a participant said, “There may be a phone call that’s required over sending an email, especially if you’re not very happy, or maybe you just need to go down to someone’s office and have a face to face. There is body language; you can read it.”

The sixth theme was the ability to assess and analyze information. One participant said that a future pharmacist should have “…a good understanding of where to go and what is quality literature, or guidelines to review for a given disease state, or problem.” Related, the participants also promoted the importance of recognizing how rapidly information is changing in health care and having the ability to deal with these changes as they emerge. For instance, one participant noted that a future pharmacist must be aware of new drugs and have the ability to incorporate them and prioritize them into practice. Curiosity and imagination was the seventh theme. Participants described the importance of asking great questions, never being satisfied with the status quo, exhibiting empathy, and searching for unique solutions. As one participant said, “It's about not being satisfied with answering a question but being able to answer their question and let that lead you someplace else.”

Self-awareness, the final theme, included the ability to both accept and receive feedback from others and having awareness of one’s impact. For instance, one participant said that the future pharmacist should have “…a certain self-awareness of where their own deficits, where the sum of them lie, and [accept] that.” In reflecting on previous discussions with residents, another participant said, “…one of the key things that I talk to residents about…is how they’re able to self-evaluate their own work and judge the quality of it.”

It is worth noting that while the overarching themes emerged as distinct from one another, they were not always mutually exclusive, and some subthemes occasionally overlapped. For example, a subtheme from theme one, “decide what’s accurate and what’s not,” had common characteristics with a subtheme from theme six, “find, evaluate, and synthesize information.”

DISCUSSION

Preparing aspiring health professionals to deliver high quality, team-based care is imperative for improving patient care and meeting health care needs. This study found that the skills and abilities believed to be critical for the job to be done in pharmacy align with Wagner’s research on skills for success in work, learning, and citizenship. As stated by Wagner, “the most successful companies in the emerging economy need a new and very different kind of worker who teams with others to continuously reinvent the machine as well as the products and services it creates (pg. 41).”16 The results of this study suggest that the participants also envisioned this new and very different kind of worker as necessary for the job to be done by pharmacy graduates. Further, research from the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AACU) supports the importance of these “cross-cutting capacities” to employers, who indicated they want more emphasis on critical thinking, complex problem-solving, written and oral communication, and applied knowledge in a real world setting.7

These findings have important implications for pharmacy education as well as other health professions. The proliferation of curriculum reform and new health professions schools, coupled with ongoing changes in health care, make this work timely and relevant. All too often, curricula emphasize vast amounts of discipline-specific knowledge at the expense of skills essential to survive in an increasingly competitive and global society. Being a professional requires specialized knowledge and skills; however, much of what is learned as a student in the classroom changes over time. Consequently, schools must foster in students the skills needed to become self-directed lifelong learners who strive for personal and professional development, thus positioning themselves for continual and positive impact on health and health care. With a rapidly evolving health care landscape, students must develop habits of mind that embrace curiosity, agility, and collaboration, and they must demonstrate the ability to lead and manage change. We also need to teach our students about their own roles, unique skillsets, and the profession’s expectations so that our graduates are better positioned to articulate what the profession can offer.

The skills identified in this study – critical thinking and problem-solving; collaboration across networks and leading by influence; agility and adaptability; initiative and entrepreneurialism; effective oral and written communication; accessing and analyzing information; curiosity and imagination; and self-awareness – are important, timely, and relevant skills for pharmacists for several reasons. First, ensuring the safe, effective, and affordable use of medications is critical if we are to improve national health care. This requires that pharmacists assume more responsibility for optimizing medications as a means toward improving care and care delivery, which, in turn, requires that pharmacists be open and adaptable to shifting away from traditional ways of working to arrive at new and creative solutions that better position them to play a much more direct role in optimizing medication use. It also requires them to be effective communicators and function in a highly, collaborative environment to advance care. Skills such as critical thinking and problem-solving are essential to arrive at new, sustainable models of care delivery that demonstrate the value-added role of pharmacists as integral team members who positively impact the quality and cost of patient care.

Preparing students for the realities of real-world health care delivery permeate conversations about curricular change as accreditors promote curriculum design.8-10 This research also contributes to a growing body of literature on the need to foster interprofessional education, including the interprofessional collaborative practice competencies from IPEC.6 Although participants in this study were not asked specifically about teamwork and interprofessional care, several of the study themes and subthemes (eg, collaboration across networks and leading by influence) reflect key behavioral expectations from IPEC, including engage diverse health care professionals who complement one’s own professional expertise, choose effective communication tools and techniques, recognize one’s limitations in skills, knowledge, and abilities, and reflect on individual and team performance. For learners of different disciplines to be ready for collaborative practice, students and instructors must better understand what the respective disciplines are emphasizing that will prepare students for practice; and work toward creating intentional programs within their curricula to foster relationships and promote the development of interprofessional collaborative practice competencies.6

Collaboration, communication, and critical thinking and problem-solving are common in interprofessional care and education models and have been emphasized as important competencies for many years. The literature on each of these competencies is vast, spanning a wide range of disciplines and educational levels.20 In The Ten Principles of Good Interdisciplinary Team Work, for example, researchers identified supportive team climate and communication strategies and structures as characteristics underpinning effective interdisciplinary work.21 Given the salience of these constructs, their presence as themes in this study is not surprising.

While collaboration, communication, and critical thinking have a long and rich history of emphasis in health professions, other themes reflect emerging ideas about education and success such as initiative and entrepreneurialism and agility and adaptability. The need to foster these characteristics likely starts early in the educational process for the professional student. Schools and faculty need to create engaged and active learning experiences, both in the classroom and in the practice setting, that emphasize initiative, innovation, critical thinking, and adaptability so that students are mindful of the importance of these skills and are assessed accordingly throughout their education and training. Preceptors and faculty alike should be able to observe these qualities in students, and have appropriate assessment instruments in place to both measure and document the level to which students demonstrate these qualities in the applied, real-world setting.

This study is an important step toward understanding how to best prepare pharmacy students for the emerging health care needs of society. At our own school, this work has enabled us to establish a common language and philosophy among our preceptors about the job to be done by pharmacists in 2020 and beyond. Having a shared philosophy helps to ensure that we are collectively designing a curriculum toward a common endpoint or outcome upon graduation from the professional program. In addition, this exercise has informed the refinement of our core competencies for the doctor of pharmacy degree program, the development of our transformed curriculum, our plans for assessment of student learning, and will continue to inform preceptor engagement and development. Further research will be critical for understanding how to best integrate the teaching, learning, and assessment of these skills within the curriculum.

The main limitations of this study are related to the sample, as participants were associated with a single school and state (North Carolina) and represented only one discipline. However, many participants engage with other pharmacists, health care professionals, and organizations by the nature of the work that they do. Given that the participants are associated with the school, it is also possible that they were previously influenced by Wagner’s framework because it has been used to help guide the school’s curriculum transformation for some time. Surveying participants prior to the breakout groups about their knowledge of Wagner’s framework could have provided additional insight into the extent to which participants may have adopted these principles.

In light of these limitations, future work could be aimed at exploring the perspectives of other disciplines to determine input from multiple professions into the job to be done by pharmacists in the future. In addition, similar research in other health professions will provide insight into the relationship of these skills with the jobs to be done in other disciplines. While this study focused specifically on pharmacist skills, it advances the efforts of health professions schools working toward identifying effective educational strategies and opportunities that adequately engage students across disciplines. In addition, it will be critical for other health professions disciplines to understand the value-added role of pharmacy in the provision of high-quality, team-based, patient-centered care. This, in turn, will promote a health care workforce that is prepared to function collaboratively in patient care and will move us closer to transforming practice and meeting the health care needs of society.

CONCLUSION

Understanding the skills and competencies needed by pharmacy graduates is critical for ensuring that educational experiences and curricula prepare them for the job to be done in today’s rapidly evolving health care system. By elucidating those skills seen as core to the pharmacist’s role by professionals, partners, and educators, this research contributes to a growing body of literature concerning the evolving roles of health care providers and provides insight into curriculum development needs in pharmacy education. Further research should examine the operationalization of these skills and their intersection with other health care professions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was funded by a 2015 AHEC Innovation Grant.

Appendix 1. Breakout Group Script

During the symposium, participants were asked to consider the job to be done by pharmacy graduates in 2020 and beyond. In the breakout groups, discussion was facilitated with a semi-structured script using two questions. These questions were written to help participants envision the job to be done by graduates of the school’s new curriculum (ie, 2020 and beyond):

1. If we aspire to create students who look like a post-graduate year 1 (PGY1) resident six months into training (“PGY 0.5”), what are those qualities and characteristics that define these individuals?

2. What do they know (knowledge), how do they behave (behaviors), what is it that they do (skills)?

Appendix 2. Example themes, subthemes, and quotes from the January 2015 UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy preceptor symposium

THEME 1: CRITICAL THINKING AND PROBLEM-SOLVING

Ask good questions (or anticipate good questions)

○ “…anticipate the intuitive question ahead of time…”

○ “…Somehow, we have to teach these future graduates what is the right question to ask for us to be able to move forward…”

Deal with vast amounts of information (Including the most frequently used medicines and prevalent diseases)

○ “…managing large group of patients. I guess what that really means is in your brain you’re able to keep pieces of discrete information kind of on hold… .RAM is the term that comes to mind like recording. [W]hat was your RAM capacity? Or what is your ability to have multiple windows open at one time without computer loss?”

○ “One thing that was unpopular when I was in school and probably still unpopular but I think extremely important is some of the traditionally medical pieces of knowledge like terminology, some diagnostics, entry level diagnostics, medical abbreviations.”

○ “I think that [my students who are halfway through] have a rich understanding of drug therapy in the most common disease states that they’re seeing.”

Figure out what’s important and what’s not (Including developing a plan of action, prioritizing projects, and managing time)

○ “…when it comes [to] recommendations or working with the team, understanding this is important. This is not as important. This is something I can put onto the side and ask.

○ “If they were to the point of being halfway through a residency year, then I would expect them to be able to handle that entire volume of patients and be able to go back to the prioritization issue. Figure out what’s important to cover in clinic today. What can we table for next time? Let’s make sure that clinic stays on time and on track and patients’ needs are being covered. I think that volume issue is something that I would look for.”

Decide what’s accurate and what’s not

○ “…recognizing when what’s in evidence-based medicine may not exactly fit your patient’s scenario…The ability to critically evaluate and apply.”

THEME 2: COLLABORATION ACROSS NETWORKS AND LEADING BY INFLUENCE

Work in teams, face-to-face and virtually (Including the ability to foster relationships across interdisciplinary teams)

○ “…Just recognizing the importance of interdisciplinary relationship, building with those relationships, more competent/aware relationships building…”

○ “I think that would be helpful for them to have worked through or seen or experienced a disagreement in the professional setting and how do you go from beginning to end and still work together and still affect patient care.”

Make your own decisions (Including having a sense of accountability, ownership, and responsibility)

○ “I think we want to create people who do actively see it as their personal responsibility to ensure that the patient gets their medication, and be responsible for that whole medication use process.”

○ “I think it’s about in terms of…committing sometimes. Sometimes our students or early residents will be given a consult to say, ‘What do you think we should do in this situation?’ And you’ll get a note that says, ‘You can do one of these seven things.’ … I think this is the best choice. Committing to a plan of action.”

○ “Because I think to me, we need practitioners who are ready to make decisions on day one. I think that is again what I find to be a differentiating factor in learners is, somewhat it’s how they approach pharmacy to begin with, but then it is also their skills status. Are they ready to take ownership and make decisions and advocate for interventions or are they still kind of a spectator or at least still on the evolution from being a spectator?”

THEME 3: AGILITY AND ADAPTABILITY

Adapt to change

○ “I think one thing I noticed in myself and I see in other residents is they progress through a PGY1 year is becoming more quickly adaptable to new patient care situations. You get a lot of practice moving between very different care environments.”

○ “…there are times for our residents that they might be serving in a CPP role. There are other times that they might be serving in a consultant role or a patient educator role or a care coordination role.”

○ “…adapt the way they engage with the patient based on what they’re hearing from or seeing from the patient.”

Work with disruptions

○ “I've heard this mentioned now three times in our discussion about that adaptability and being able to recognize when you need to go, maybe you’re going to do something in the clinic room or the patient room or wherever that’s totally different than what you thought and you don’t even do that, that you thought you were going to do. Students do have trouble changing rails on that sometimes.”

THEME 4: INITIATIVE AND ENTREPRENEURIALISM

Proactive, self-starters

○ “They're not just sitting there waiting for it to be told what to do.”

○ “…I think being proactive within that system to participate in the recognition [of the problem] and the solution.”

Actively look for ways to improve the systems around you (Including advocating for the profession and professional development)

○ “…what about graduates who recognize opportunity for change? Try to come up with better solutions for improving whatever, whether it’s patient care, the system they’re working in….Advocates for advancing the profession.”

Not be afraid to try and fail (Including having confidence and being “appropriately assertive”)

○ “…the confidence in yourself and the ability to question other health care providers when something doesn’t seem right.”

○ “I think it’s almost the ability to fail, so most of us come out of school having never failed and so residency takes a candidate who has succeeded over and over and then finally reaches capacity and you have to deal with personal failure.”

THEME 5: EFFECTIVE ORAL AND WRITTEN COMMUNICATION

Clear and concise writing, speaking, and presenting with focus, energy, and passion

○ “…get their charting done, which involves good communication. It involves efficiency. It involves the ability to document effectively and to ask for help when they need it.”

○ “Sometimes all you have is an opportunity to do a two-minute elevator pitch, and how do you do that? Maybe note both written and verbal communication that’s concise and compelling, and effective and appropriate.”

Know how and when to use different levels of communication

○ “I think some of our subgroups have also talked about the ability to distinguish between which ones are appropriate at what times. There may be a phone call that’s required over sending an email, especially if you’re not very happy, or maybe you just need to go down to someone’s office and have a face to face. There is body language; you can read it.”

○ “There’s also communications with patients, providers, and pharmacists. Students understanding both the language, the complexity and the depth that you go into, when you’re explaining a concept to a physician who asked a question and really what they want to know is the endpoint. But when you’re talking to your preceptor, you can go through your entire thought process, being able to give the same message to three people very differently based on who your customer is.”

THEME 6: ACCESSING AND ANALYZING INFORMATION

Find, evaluate, and synthesize information

○ “… has a good understanding of where to go and what is quality literature, or guidelines to review for a given disease state or problem.”

○ “…a commitment to understanding what the health care system looks like and recognizing that part of understanding the health care system is not just learning it once. It’s keeping up with it.”

Understand how rapidly information is changing and be able to deal with that

○ “…New drugs as they come out, how to incorporate them and prioritize them into your practice. Where they’re going to fit into your steady guideline. Am I going to add this or am I going to revise it or not. I guess, it’s capability to acquire knowledge as it evolves.”

THEME 7: CURIOSITY AND IMAGINATION

Never be satisfied with the status quo

○ “It’s about not being satisfied with answering a question but being able to answer their question and let that lead you someplace else.”

○ “The ones who are most successful are those who take the guidelines that I support to give them, but they ask the further question, why?”

Empathy

○ “…have an appreciation for our patients, because you’re going to encounter barriers they have to go through due to Medicare, diversity, that kind of complexity.”

○ “…teaching the student that the patient’s at the center, and it doesn’t matter the practice site.”

THEME 8: SELF-AWARENESS

Self-awareness (Including receiving/accepting feedback from others and awareness of one’s impact)

○ “…a certain self-awareness of where their own deficits, where the sum of them lie, and accepting that. How do you identify that, because we’re prepping them to be able to speak to their vulnerabilities or deficiencies that they have, that conversation prior to getting to the site.”

○ “…do they recognize their strengths and their limitation and their areas of improvement and things like that.”

○ “…one of the key things that I talk to residents about at this point is how they’re able to self-evaluate their own work and judge the quality of it.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Informing the Future: Critical Issues In Health. 4th ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12014&page=R1. Accessed June 8, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irby DM, Cooke M, O’Brien BC. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):220–227. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c88449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berwick DM, Finkelstein JA. Preparing medical students for the continual improvement of health and health care: Abraham Flexner and the new “public interest.”. Acad Med. 2010;85(9 Suppl):S56–S65. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ead779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speedie MK, Baldwin JN, Carter RA, Raehl CL, Yanchick VA, Maine LL. Cultivating ‘habits of mind’ in the scholarly pharmacy clinician: report of the 2011-2012 Argus Commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(6):Article S3. doi: 10.5688/ajpe766S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/ipecreport.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- 7.Association of American Colleges and Universities. It takes more than a major: employer priorities for college learning and student success. http://www.aacu.org/leap/documents/2013_employersurvey.pdf. April 10, 2013. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- 8.Functions and structure of a medical school. Standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the M.D. degree. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. (2015). http://lcme.org/publications/. Accessed June 8, 2016. [PubMed]

- 9.Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standards 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. 2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- 10.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2011). The essentials of master’s education in nursing. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/MasEssentials96.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2016.

- 11.National League for Nursing. Advocacy and public policy. http://www.nln.org/advocacy-public-policy. Accessed June 6, 2016.

- 12.Jungnickel PW, Kelley KW, Hammer DP, Haines ST, Marlowe KF. Addressing competencies for the future in the professional curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 156. doi: 10.5688/aj7308156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke JM, Miller WA, Spencer AP, et al. Clinical pharmacist competencies. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):806–815. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes 2013. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christensen CM, Anthony SD, Berstell G, Nitterhouse D. Finding the right job for your product. MIT Sloan Manag Rev. 2007;48(3):38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner T. The Global Achievement Gap: Why Even Our Best Schools Don’t Teach the New Survival Skills Our Children Need – and What We Can Do About It. New York, NY: Perseus Books Group; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth MT, Mumper RJ, Singleton SF, et al. A renaissance in pharmacy education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. N C Med J. 2011;75(1):48–52. doi: 10.18043/ncm.75.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Texas Computer Education Association. In Seven Survival Skills for the 21stCentury: From Tony Wagner’s The Achievement Gap. [PowerPoint slides]. http://slideplayer.com/slide/6648735/. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- 20.Baker DP, Gustafson S, Beaubien JM, Salas E, Barach P. Medical teamwork and patient safety: The evidence-based relation. Literature review. AHRQ Publication No. 05–0053, April 2005. US Department of Health & Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/final-reports/medteam/. Accessed August 9, 2017.

- 21.Nancarrow SA, Booth A, Ariss S, Smith T, Enderby P, Roots A. Ten principles of good interdisciplinary team work. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]