Abstract

Objective. To identify and describe the available quantitative tools that assess interprofessional education (IPE) relevant to pharmacy education.

Methods. A systematic approach was used to identify quantitative IPE assessment tools relevant to pharmacy education. The search strategy included the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education Resource Exchange (Nexus) website, a systematic search of the literature, and a manual search of journals deemed likely to include relevant tools.

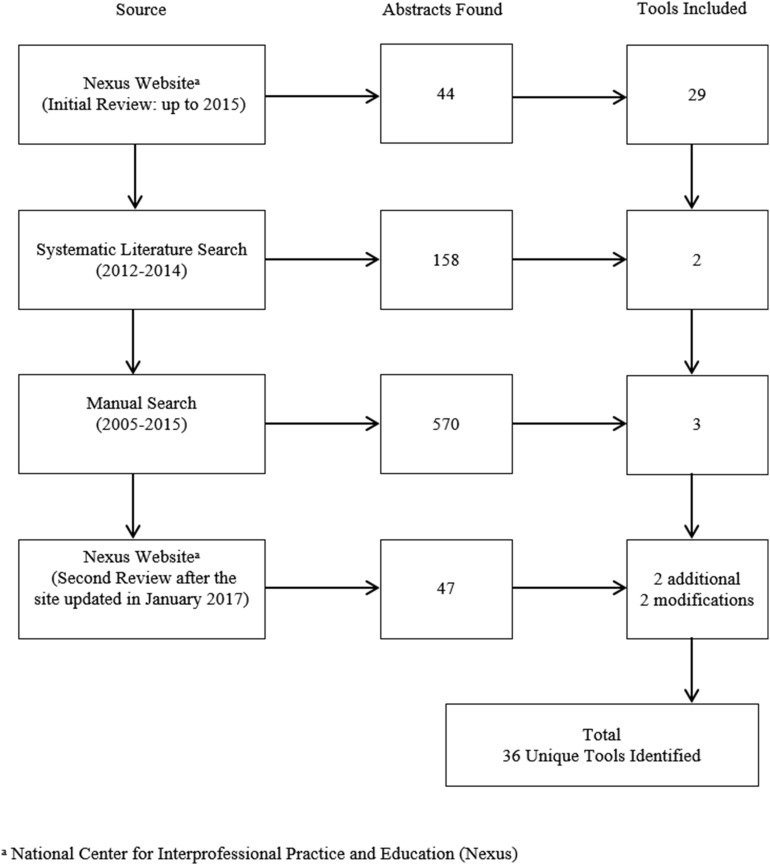

Results. The search identified a total of 44 tools from the Nexus website, 158 abstracts from the systematic literature search, and 570 abstracts from the manual search. A total of 36 assessment tools met the criteria to be included in the summary, and their application to IPE relevant to pharmacy education was discussed.

Conclusion. Each of the tools has advantages and disadvantages. No single comprehensive tool exists to fulfill assessment needs. However, numerous tools are available that can be mapped to IPE-related accreditation standards for pharmacy education.

Keywords: interprofessional education, assessment, evaluation, pharmacy, accreditation

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization recognizes interprofessional education (IPE) when students from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes.1 Because of the increasing recognition of the value of interprofessional collaborative practice, national competencies have been developed in the United States to facilitate the delivery of IPE within an academic curriculum.2 Training future health care providers for interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP) is an important step in achieving the “Triple Aim” of improved patient care and experiences, population health, and reduced costs.3

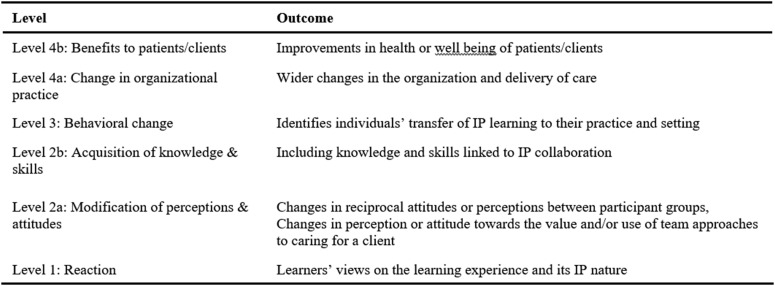

While approaches to IPE have expanded, assessment in this area continues to develop, and further research in this area is warranted.2 Assessment approaches for IPE are varied, and best practices have not been identified. Recent reports from the Institute of Medicine have called for formative and summative assessment of IPE using qualitative and quantitative methods.4,5 Also, Barr’s modified Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy of assessment is recommended as a framework for IPE.6 Using this framework, experts recommend the IPE field include higher order assessments such as changes in behaviors, care delivery, patient satisfaction, and patient outcomes.7,8 Specific quantitative measurement tools for assessing IPE are available in the literature and continue to expand.9,10 However, pharmacy educators are challenged with increased emphasis on IPE delivery and assessment as stated in the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) outcomes11 and the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) national standards.12 The CAPE outcomes discuss preparing pharmacy students to be collaborators on the health care team. In addition, the ACPE standards have an increased focus on IPE and specifically require documentation of student assessment outcomes in the Pre-Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE) and APPE curriculum. A primer for implementing IPE within pharmacy curricula suggested that each school develop an overall assessment plan; however, an extensive review of specific assessment strategies and tools was not the sole focus.13 A recent review focusing on assessment of interprofessional teamwork in medical education is useful.14 However, literature summarizing IPE assessment strategies that apply to pharmacy education is lacking. The purpose of this review is to identify and briefly describe the quantitative tools available that assess IPE as it pertains to pharmacy education.

METHODS

A systematic approach was used to identify quantitative IPE assessment tools relevant to pharmacy education, beginning with a review of the tools available on the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education Resource Exchange (Nexus) website.9 This widely recognized source for high-quality measurement instruments included tools initially identified from a curated selection process15 that used a comprehensive, systematic review in 2012.16 Several more tools were subsequently added through a peer review process. All tools posted on the Nexus website up to September 2015 were analyzed for inclusion in the initial review. Following acceptance of this manuscript by the Journal, but prior to publication, the Nexus website updated the assessment and evaluation collection in January 2017. A second review of the website was conducted to include any updated or additional tools in August 2017.

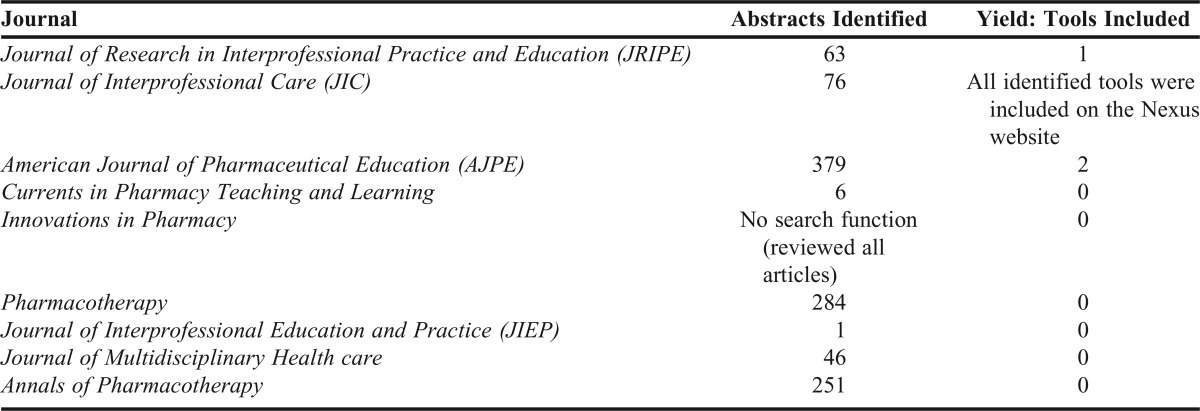

To identify additional tools published since 2012, a systematic search of the literature was conducted with the assistance of health sciences librarians adapting the previous search strategy16 for years 2012-2014. Search terms included interprofessional, interdisciplinary, interoccupation, interinstitution, interdepartment, interorganization, multiprofessional, multidisciplinary, multi-occupation, multi-institution, multi-organization, education, practice, instrument, questionnaire, survey, scale, team, and collaboration. Abstracts were reviewed. Finally, a manual search of journals deemed likely to include relevant assessment tools was conducted (January 2005-June 2015) using the following terms: interprofessional, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, evaluation, and assessment. Table 1 lists the journals used in the manual search.

Table 1.

Journals Included in Manual Search

Assessment tools were included if the publication included a copy of the tool and if it assessed knowledge, skills, behaviors, and/or attitudes consistent with the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) domains2 (values, knowledge of roles, communication, teamwork) or CAPE 2013 outcomes11 related to interprofessional collaboration. Thus, included tools measured the following: attitudes toward/willingness to work in interprofessional teams, professional identity in relation to other health professionals, quality of team interactions/function (how well the team members work together), and/or efficacy of team interactions (patient outcomes). Tools were excluded if they measured a specific learning session only or had limited or no ability to assess students in other activities or curricula. Tools also were excluded if they did not include pharmacists or student pharmacists as part of the health care team assessed, unless they had direct applicability to the role of pharmacists on health care teams and could be potentially applied to pharmacy students (ie, did not include language that precluded pharmacists or student pharmacists or assessed a practice situation in which pharmacists would not typically participate).

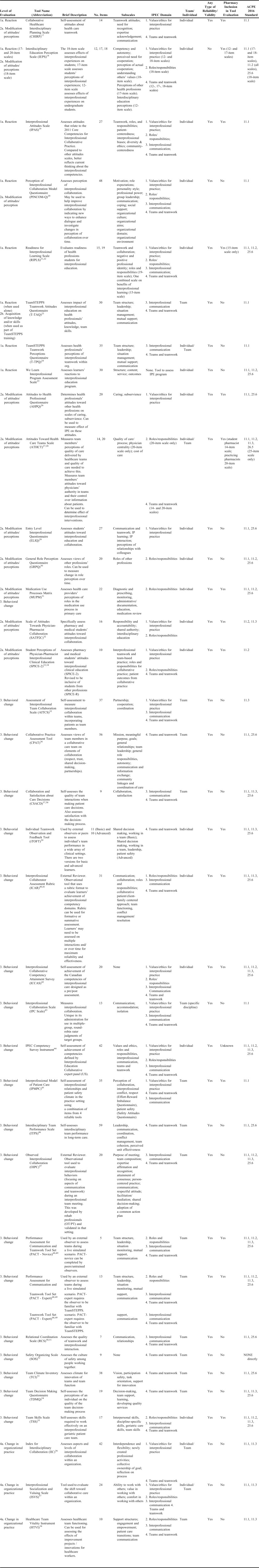

All assessment tools included were categorized by level of evaluation using the Kirkpatrick outcomes model6 and inclusion of pharmacists/student pharmacists (Figure 1). Any information reported about reliability/validity also was included. To aid end users, the tools were secondarily categorized by IPEC domain (values, roles, communication, teamwork)2 and ACPE Standards 201612 related to interprofessional education (Standards 11.1-11.3 and 25.6). All of the categorization was completed by one author. If there were questions, the group of authors discussed them and reached a consensus.

Figure 1.

Kirkpatrick Assessment Model

RESULTS

The search strategy identified 44 tools from the Nexus website upon initial review and an additional two tools and two updates from the second review, 158 abstracts from the systematic literature search (117 from MEDLINE, one from ERIC, 40 from CINAHL), and 570 abstracts from the manual search of relevant journals (Figure 2). Thirty-six assessment tools met the criteria to be included in the summary, 29 from the Nexus website, two from the literature search, and three from the manual search of relevant journals (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Diagram of Search Strategy and Yielded Results

Table 2.

Quantitative Tools to Assess Interprofessional Education Applicable for Pharmacy Education

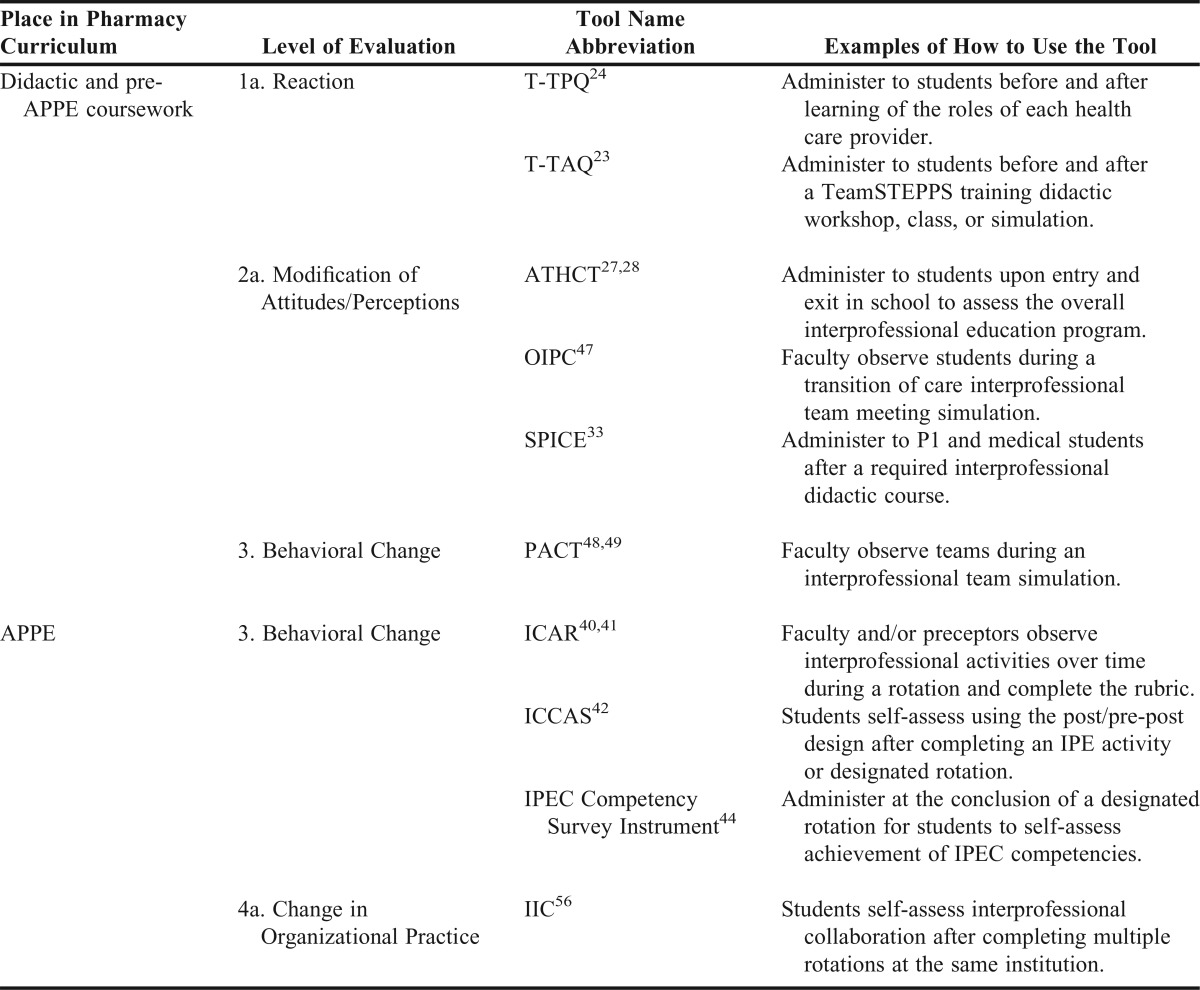

Concerning categorization by Kirkpatrick assessment levels, eight tools were found to assess reaction, 11 tools assessed modification of attitudes/perceptions, one tool assessed acquisition of knowledge or skills, 19 tools assessed behavior change, and three tools assessed change in organizational practice. The length of the tools ranged from five to 59 items. Fifteen tools were designed to assess an individual member of a team; 15 tools were designed to assess the team as a whole, and four tools could be used to assess an individual or a team. The majority of tools (58%) did not include a pharmacist or student pharmacist in the validity or reliability testing of the tool. The authors provided examples of how to use some of the selected tools for assessment within the pharmacy curricula (Table 3). These are examples for pharmacy educators, but this is not intended to serve as “best in class” recommendations.

Table 3.

Examples of Selected Assessment Tools and Their Application to Pharmacy Education

DISCUSSION

Recent publications affirm that the emphasis on interprofessional education is going to be long-standing.2,3,5,12 As colleges and schools of pharmacy develop IPE opportunities for students, the need for quality assessment measures is clear. A review like this one, the first to identify published IPE assessment tools relevant to pharmacy, would serve as a starting point for developing a quantitative assessment and resource plan. However, there is also a need for qualitative assessment of IPE activities. In fact, mixed methods evaluations, both quantitative and qualitative, are recommended; specifically, if the evaluation questions incorporate the examination of both what and why.4-7 And while a fairly robust number of quantitative tools have been identified, when evaluating them for placement into Kirkpatrick’s outcomes, there is a lack of tools evaluating the top two levels: change in organizational practice and benefits to patients/clients.8

When developing an assessment plan, one must consider curricular mapping of quantitative and qualitative measures to educational standards for the profession in addition to the IPEC core competencies.2 It is also important for those developing the plan to be mindful of overassessment and its potential negative impact on the ability to obtain robust evaluation results.13 While Table 2 lists and categorizes the available quantitative tools, below is a more detailed summary of the applicability of certain select tools (presented according to the Kirkpatrick evaluation framework6) to provide additional context.

Level 1: Reaction

These tools assess the readiness for students or health care providers to engage in interprofessional activities. Tools evaluating this level are most important to include early in the IPE implementation process. However, once IPE becomes an established component of the educational culture, the utility of these tools becomes less apparent. It should be noted that the updates to the Nexus website limited the inclusion of these types of tools and increased the emphasis of tools measuring skills, behaviors, and outcomes. Among the tools in the reaction level of evaluation, the two TeamSTEPPS tools (T-TAQ and T-TPQ) stand out in that they measure reaction when taken individually and can be used as stand-alone tools without full implementation of the TeamSTEPPS training. If the activity has exposed the students to core components of the TeamSTEPPS training, both the T-TPQ and T-TAQ tools,23,24 can be used to evaluate “team-wide” if TeamSTEPPS training has affected teams overall. An additional measure of reaction is the learner’s opinions of the IPE program or activity. The We Learn Interprofessional Program Assessment Scale25 was developed to collect feedback useful for interprofessional educators designing IPE and may be useful in the didactic portion of the pharmacy curriculum.

Level 2: Modification of Attitudes and Perceptions

The tools in this category assess attitudes toward the values and/or use of interprofessional teams in education and/or patient care. Among all of the tools that assess this level of evaluation, the Attitudes Toward Health Care Team Scale (ATHCT) stands out as it has been evaluated in both pharmacists27 and pharmacy students.28 While its explicit use as a team or individual assessment is not clearly noted, it appears that it could be used in either way. It is a useful tool in measuring learners’ perceptions of interprofessional collaboration as it relates to patient care. The General Role Perception Questionnaire (GRPQ) assesses an individual’s views of the roles of other health professions30 and can be used to measure the change in role perception with repeated use. The Medicine Use Processes Matrix (MUPM) is a tool that evaluates an individual’s understanding of the medication use process in primary care,31 specifically the perceptions of the roles involved in this process. A drawback to this tool is that it is based in primary care and cannot be applied outside of primary care practice, thus limiting its utility for pharmacists learning and practicing in other settings.

Two additional tools evaluating this level are the Scale of Attitudes Toward Physician-Pharmacist Collaboration (SATP2C)32 and Student Perceptions of Physician-Pharmacist Interprofessional Clinical Education (SPICE-2).33 These measures of attitudes may be most useful in a pre/post design to evaluate a particular IPE activity. Both of these tools were designed to specifically include pharmacy and medical students; there are pros and cons to these tools because there are only two professions learners involved in the development and validation process. It should be noted that the SPICE-2 tool was modified and validated in additional learners from other professions by revising the wording of the original questions and changing the name of the tool to Student Perceptions of Interprofessional Clinical Education Revised (SPICE-R).34

Level 3: Behavioral Change

The tools in this category assess quality of interactions or perceptions of roles of each member of the patient care team. It is clear that much attention has been dedicated to this evaluation level over the past decade, as the majority of tools identified for this review, are at this level. While several of the tools have been developed to assess individuals, the majority have been developed to assess teams and evaluate overall team behavior.

There are two tools designed to assess attainment of IPE competencies. The IPEC Competency Survey Instrument can be used in assessing IPE program design and outcomes; it is based on the competencies adopted by organizations in the United States.44 However, the tool was designed as a self-assessment; it is unlikely that self-assessment of competencies alone, will be sufficient to fulfill ACPE accreditation standards. The second available tool is the Interprofessional Collaborative Competency Attainment Survey (ICCAS), which is also a self-assessment of IPE competencies.42 It evaluates the Canadian competencies of interprofessional care and was intended to be used in a post-pre/post-design. While neither are observational tools, both can be used to improve learners’ self-awareness of the competencies and identify areas for improvement. Further, both tools would likely be useful during a range of IPE experiences: didactic, simulation or APPEs in the pharmacy curriculum.

The Team Skills Scale (TSS) is a self-assessment of skills required to work effectively on an interprofessional geriatric patient care team.55 The TSS is commonly used in conjunction with the ATHCT.27,28 While not specific to the duration of being a team member and lacking student reflection on a specific team interaction, it may serve as a useful tool during APPE or longitudinal pre-APPE IPE activities focusing on the geriatric patient population.

A few tools have been developed to assess individual learners working as part of an interprofessional team. They were developed to use an external observer including faculty, preceptors, interprofessional preceptors for a 360-evaluation, and peers. The Interprofessional Collaborator Assessment Rubric (ICAR) includes items developed to align with the Canadian competencies of interprofessional care.40 The reliability of the tool improves with repeated observations. A modified version of the ICAR with the same constructs, but condensed number of items is also available.41 The Individual Teamwork Observation and Feedback Tool (iTOFT) was developed with a limited number of items to emphasize the feasibility of use in clinical settings.39 All of these tools may be useful to assess students during APPEs in the pharmacy curriculum.

Twelve tools addressing Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy level 3 (behavioral change) and described as tools assessing teams as a whole were identified. These tools can be used on either a longitudinal basis or for a one-time IPE event and be completed by an external observer or be administered in the workplace. Relative to the tools identified to be used in a longitudinal manner, the Collaborative Practice Assessment Tool (CPAT) is geared toward a team working together in a patient care setting for a long period of time.36 It would not be beneficial and is not recommended for assessing brief team interactions. Similarly, the Team Decision Making Questionnaire (TDMQ) is most applicable to long-term teams in a clinical practice.54 It can be used in conjunction with a tool measuring team dynamics to identify areas for team development and improvement. And, while its description notes the tool as assessing interprofessional team quality, the items appear more applicable to the individual member and how the team decision-making process specifically helps them. The Interprofessional Model of Patient Care (IPMPC) is a combination of scales (modification of the Effort-Reward Imbalance and Safety Attitudes questionnaires) measuring interprofessional team relationships. It is best used before and after an intervention with an existing team to compare improvement over time.45 This tool must be used twice to measure a difference, and it is not a tool to use before an experience with a new, naïve team; it is to be administered to existing teams. From the standpoint of applying this to pharmacy education, the question is whether this tool would be able to detect differences during the common four to eight weeks of an APPE rotation given that these are typical “de novo” teams.

Contrary to the tools evaluating behavior change longitudinally and among existing teams, other tools are available to evaluate behavior change resulting from a single IPE experience and may have more applicability in the pharmacy curriculum. The first of these three tools is the Collaboration and Satisfaction About Care Decisions (CSACD).37,38 Designed to be used after a single patient encounter, this tool may be considered when assessing interactions in an interprofessional team objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) or for a specific encounter during APPEs. The other single experience tools to measure behavior change are unique in their use and focus. Specifically, the Interprofessional Collaboration (IPC) scale is designed for individuals to assess team members from other professions.43 If used, professional labels may need to be altered depending on the role of the evaluator and evaluatee. For teams with more than two professions, multiple versions of the evaluation would need to be completed as the evaluator completes one evaluation for each member of the different professions on the team. Finally, the Safety Organizing Scale (SOS) tool educates health care providers about elements of safety culture behaviors with a goal to improve safety outcomes.52 Tool items do not specify the application to an interprofessional team.

Two additional tools evaluating behavior change are completed by external observers as opposed to the participants themselves and can be used for newly formed or established teams. The first tool, the Performance Assessment for Communication and Teamwork (PACT), is a useful behavioral observation tool, particularly when using the Novice version.48,49 It could perceivably be used to evaluate teams during patient care APPEs or a simulation. It is best to evaluate synchronous teams during a specific patient encounter. The second tool completed by an external observer is the Observed Interprofessional Collaboration (OIPC).47 This tool is applied when observing team meetings where a team discusses multiple patients and is not making immediate patient-care decisions at the point of patient care. This tool can also be useful on APPE rotations or during simulations that involve the transition of care or discharge planning meetings.

Another tool measuring behavior change is the Assessment of Interprofessional Team Collaboration Scale (AITCS) that is used to evaluate a team in the workplace environment.35 While designed to be implemented in a workplace setting as opposed to an educational setting, it was developed in response to the limitations of existing tools; specifically, those lacking the incorporation of the patient as a team member. While other tools exist that measure behavior change, they are either not available for free use (Relational Coordination Scale50,51 and Team Climate Inventory53) or only available from the author directly (Interdisciplinary Team Performance Scale46).

Level 4. Change in Organizational Practice

To date, the highest level of Kirkpatrick’s hierarchy that appears to be evaluated among the available IPE assessment tools is level 4, change in organizational practice. The purpose of these tools is to assess interprofessional collaboration at an organizational level. Three tools addressing this are the Index for Interdisciplinary Collaboration (IIC),56 the Interprofessional Socialization and Valuing Scale (ISVS),57 and the Healthcare Team Vitality Instrument (HTVI).58 While the IIC and ISVS can be used for either individual (to evaluate perceptions of collaboration) or team assessment, the HTVI is intended only for team assessment. Specifically, the use of either the IIC or ISVS can help to identify if an intervention results in changes in the perception of the team’s view of its collaboration.

Limitations

Limitations to this systematic review are threefold. First, tools were included only if they were perceived to be relevant to pharmacy education, which excludes numerous tools that can be used to assess interprofessional teams. For example, a recent review of IPE assessments applicable to medical education includes additional tools that could be used.14 The Communication and Teamwork Skills (CATS)59 and Teamwork Mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise (T-MEX)60 tools recommended in this medical education review are important to note, since the ACPE standards emphasize including prescribers in IPE, and it is likely many schools will have medical students involved in interprofessional activities.

Second, only quantitative tools were included in this review. Qualitative tools or methods and mixed methods (qualitative plus quantitative) can also contribute important information to an assessment plan in addition to quantitative data alone.5,8 For example, Harris and colleagues outline an analytical strategy using qualitative coding techniques that could be used to assess interprofessional case discussions in practice.61 However, qualitative methods are time consuming to evaluate with large numbers of students, and thus are likely to have limited reach.

Third, the systematic review process used may not have identified all tools available and applicable to pharmacy education. In fact, the authors collectively know of a few additional tools that were not uncovered in this review process. These tools include the Team Performance Scale (TPS),62 with reliability testing completed in medical62 and pharmacy63 students using team-based learning, the McMaster-Ottawa Scale64 that has been used in team observed structured clinical encounter (TOSCE) performance evaluation, and the KidSIM Team Performance Scale65 used to measure interprofessional student team behaviors after experiencing an acute-care simulation curriculum. These tools may have application for use in pharmacy education.

Finally, the Interprofessional Collaborative Organization Map and Preparedness Assessment (IP-COMPASS),66 Team Development Measure (TDM),67 and Assessment for Collaborative Environments (ACE-15)68 would likely not be useful for assessment of pharmacy learners, but could be beneficial to measure the clinical learning environment and culture for IPE in APPE settings.

CONCLUSION

Thirty-six quantitative assessment tools have been made available to assess interprofessional education for teams that include or are applicable to the pharmacists or pharmacy students. Of the available tools, the majority assesses the Kirkpatrick level 3 (behavioral change). Each of the tools summarized presents advantages and disadvantages. At this time, no one comprehensive tool exists to fulfill assessment needs for appropriately assessing interprofessional education competencies as a whole. However, numerous tools are available that can be mapped to all IPE-related accreditation standards in ACPE Standards 2016. When developing an assessment plan, we recommend the use of a cadre of quantitative tools in addition to reflective writing and/or qualitative tools to assess student progression and development of interprofessional collaborator competency. We recommend development of future tools that require external observation of individual and team behavior, change in organizational practice, and patient benefits that are intended to be used for both short-term and newly formed teams of learners. In addition, performing additional validation of tools that did not include pharmacy learners and comparing the utility of various tools in pharmacy education settings could be considered for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The team would like to express its appreciation to Jennifer McDaniel (Virginia Commonwealth University) and Terry Jankowski (University of Washington) for their assistance with building the search strategy and performing the literature search involved in this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. 2010. World Health Organization. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2015. [PubMed]

- 2.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. 2011. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/ipecreport.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 3.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Affairs. 2008;27:759–769. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assessing health professional education. workshop summary. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18738/assessing-health-professional-education-workshop-summary. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 5.Measuring the impact of interprofessional education on collaborative practice and patient outcomes. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/21726/measuring-the-impact-of-interprofessional-education-on-collaborative-practice-and-patient-outcomes. Accessed November 1, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Barr H, Koppel I, Reeves S, Hammick M, Freeth D. Effective Interprofessional Education: Argument, Assumption and Evidence. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeves S, Boet S, Kitto S. Interprofessional education and practice guide no. 3: evaluating interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:305–312. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.1003637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thistlewaite J, Kumar K, Moran M, Saunders R, Carr S. Exploratory review of pre-qualification interprofessional education evaluations. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(4):292–297. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.985292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nexus Resource Exchange. Collection of existing interprofessional practice and education measurement instruments. National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education. https://nexusipe.org/advancing/assessment-evaluation. Accessed August 6, 2017.

- 10.Blue AV, Chesluk BJ, Conforti LN, et al. Assessment and evaluation in interprofessional education exploring the field. J Allied Health. 2015;44:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 62. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. 2016. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Chicago, IL. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016FINAL.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 13.Kahaleh AA, Danielson J, Franson KL, Nuffer WA, Umland EM. An interprofessional education panel on development, implementation, and assessment strategies. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(6):Article 78. doi: 10.5688/ajpe79678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Havyer RD, Nelson DR, Wingo MT, et al. Addressing the interprofessional collaboration competencies of the Association of American Medical Colleges: a systematic review of assessment instruments in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(6):865–888. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nexus Resource Exchange. Assessing IPECP: The selection process for the national center’s new resource exchange collection. National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education. https://nexusipe.org/informing/about-national-center/news/assessing-ipecp-selection-process-national-centers-new-resource. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 16.An inventory of quantitative tools measuring interprofessional education and collaborative practice outcomes. Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC). August 2012. http://rcrc.brandeis.edu/pdfs/Canadian%20Interprofessional%20Health%20Collaborative%20report.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- 17.Hollar D, Hobgood C, Foster B, Aleman M. Concurrent validation of CHIRP, a new instrument for measuring health care student attitudes towards interdisciplinary teamwork. J Appl Meas. 2012;13(4):360–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawk C, Buckwalte K, Byrd L, Cigelman S, Dofman L, Ferguson K. Health professions student’s perceptions of interprofessional relationships. Acad Med. 2002;77(4):354–357. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200204000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norris J, Carpenter JG, Eaton J, et al. The development and validation of the interprofessional attitudes scale: assessing the interprofessional attitudes of students in the health professions. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1394–1400. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odegard A, Strype J. Perceptions of interprofessional collaboration within child mental health care in Norway. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(3):286–296. doi: 10.1080/13561820902739981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS) Med Educ. 1999;33(2):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Forristall J, Flynn K. Attitudes of health sciences students towards interprofessional teamwork and education. Learn Health Soc Care. 2008;7(3):146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker DP, Krokos KJ, Amodeo AM. TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire (T-TAQ) Manual. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Institutes for Research. TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire (T-TPQ) Manual. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald CJ, Archibald D, Trumpower DL, et al. Designing and operationalizing a toolkit of bilingual interprofessional education assessment instruments. J Res Interprof Educ. 2010;13:304–316. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindqvist S, Duncan A, Shepstone L, Watts F, Pearce S. Development of the ‘Attitudes to Health Professional Questionnaire’ (AHPQ): a measure to assess interprofessional attitudes. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(3):269–279. doi: 10.1080/13561820400026071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heinemann GD, Schmitt MH, Farrel MH, Brallier SA. Development of an attitude towards health care team scale. Eval Health Prof. 1999;22(1):123–142. doi: 10.1177/01632789922034202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Forristall J, Flynn K. Attitudes of health sciences students towards interprofessional teamwork and education. Learn Health Soc Care. 2008;7(3):146–156. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pollard KC, Miers ME, Gilchrist M. Collaborative learning for collaborative working? Initial findings from a longitudinal study of health and social care students. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12(4):346–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackay S. The role perception questionnaire (RPQ): a tool for assessing undergraduate students’ perceptions of the role of other professions. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(3):289–302. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001731331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrell B, Pottie K, Woodend K, et al. Developing a tool to measure contributions to medication-related processes in family practice. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(1):17–29. doi: 10.1080/13561820701828845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Winkle L, Fjortoft N, Hojat M. Validation of an instrument to measure pharmacy and medical students’ attitudes toward physician-pharmacist collaboration. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:Article 178. doi: 10.5688/ajpe759178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zorek JA, Fike DS, Eickhoff JC, et al. Refinement and validation of the student perceptions of the physician-pharmacist interprofessional clinical education instrument. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(3):Article 47. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dominquez DG, Fike DS, MacLaughlin ES, Zorek JA. A comparsion of the validity of two instruments assessing health professional student perceptions of interprofessional education and practice. J Interprof Care. 2015;29(2):144–149. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.947360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orchard CA, King GA, Khalili H, Bezzina MB. Assessment of interprofessional team collaboration scale (AITCS): development and testing of the instrument. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2012;32(1):58–67. doi: 10.1002/chp.21123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schroder C, Medvew J, Paterson M, et al. Development and pilot testing of the collaborative practice assessment tool. J Interprof Care. 2011;25:189–195. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.532620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baggs JG. Development of an instrument to measure collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20:176–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20010176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dieleman SL, Farris KB, Feeny D, Johnson JA, Tsuyuki RT, Brilliant S. Primary health care teams: team members’ perceptions of the collaborative process. J Interprof Care. 2004;18(1):75–78. doi: 10.1080/13561820410001639370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thistlethwaite J, Moran M, Dunston R, et al. Introducing the individual teamwork observation and feedback tool (iTOFT): development and description of a new measure. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(4):526–528. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2016.1169262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curran V, Casimiro L, Banfield V, et al. Interprofessional collaborator assessment rubric. Academic Health Council. http://www.med.mun.ca/getdoc/b78eb859-6c13-4f2f-9712-f50f1c67c863/ICAR.aspx. Accessed October 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curran V, Hayward M, Curtis B, Murphy S. Interprofessional collaborator assessment rubric. Modified version 2013. http://www.med.mun.ca/getattachment/a943e5b4-907a-4cb783143610f4f6e386/ICAR_Modified_Final. pdf. aspx. Accessed August 6, 2017.

- 42.Archibold D, Trumpower D, MacDonald C. Validation of the interprofessional collaborative competency attainment survey (ICCAS) J Interprof Care. 2014;28:553–558. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.917407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kenaszchuk C, Reeves S, Nicholas D, Zwarenstein M. Validity and reliability of a multiple-group measurement scale for interprofessional collaboration. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(83):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dow AW, DiazGranados D, Mazmania PE, Retchin SM. An exploratory study of an assessment tool derived from the competencies of the interprofessional education collaborative. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(4):299–304. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.891573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manojlovich M, Kerr M, Davies B, Squires J, Mallick R, Rodger G. Achieving a climate for patient safety by focusing on relationships. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(6):579–584. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Temkin-Greener H, Gross D, Kunitz SJ, Mukamel D. Measuring interdisciplinary team performance in a long-term care setting. Med Care. 2004;42(5):472–481. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124306.28397.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Careau E, Vincent C, Swaine B. Observed Interprofessional Collaboration (OIPC) during interdisciplinary team meetings: development and validation of a tool in a rehabilitation setting. J Res Interprof Prac Educ. 2014;4.1:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chiu C, Brock D, Abu-Rish E. Performance assessment of communication and teamwork (PACT) tool set. Center for Interprofessional Education, Research, and Practice; University of Washington. http://collaborate.uw.edu/tools-and-curricula/tools-for-evaluation/performance-assessment-of-communication-and-teamwork-pact-t. Accessed November 9, 2015.

- 49.Chiu C, Zierler B, Brock D, Demiris G, Taibi D, Scott C. Development and Validation of Performance Assessment Tools for Interprofessional Communication and Teamwork (PACT) Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2014. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gittell JH, Fairfield KM, Bierbaum B, et al. Impact of relational coordination on quality of care, postoperative pain and function, and length of stay: a nine-hospital study of surgical patients. Med Care. 2000;38(8):807–819. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nadolski GJ, Bell MA, Brewer BB, Frankel RM, Cushing HE, Brokaw JJ. Evaluating the quality of interaction between medical students and nurses in a large teaching hospital. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogus T, Sutcliffe K. The safety organizing scale development and validation of a behavioral measure of safety culture in hospital nursing units. Med Care. 2007;45(1):46–54. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000244635.61178.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson NR, West MA. Measuring climate for work group innovation: development and validation of the team climate inventory. J Org Behavior. 1998;19:235–258. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Batorowicz B, Shepherd TA. Measuring the quality of transdisciplinary teams. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(6):612–620. doi: 10.1080/13561820802303664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grymonpre R, van Ineveld C, Nelson M, et al. See it-do it-learn it: learning interprofessional collaboration in the clinical context. J Res Interprof Prac Educ. 2010;1(2):127–144. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oliver DP, Wittenberg-Lyles EM, Day M. Measuring interdisciplinary perceptions of collaboration on hospice teams. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007;24(1):49–53. doi: 10.1177/1049909106295283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.King G, Shaw L, Orchard CA, Miller S. The interprofessional socialization and valuing scale: a tool for evaluating the shift toward collaborative care approaches in health care settings. Work. 2010;35(1):77–85. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Upenieks VV, Lee EA, Flanagan ME, Doebbeling BN. Health care team vitality instrument (HTVI): developing a tool assessing health care team functioning. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(1):168–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frankel A, Gardner R, Mayard L, Kelly A. Using the communication and teamwork skills (CATS) assessment to measure health care team performance. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(9):549–558. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olupeliyawa A, O’Sullivan A, Hughes C, Balasooriya C. The teamwork mini-clinical evaluation exercise (TMEX): a workplace-based assessment focusing on collaborative competencies in health care. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):359–365. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harris M, Greaves F, Gunn L, et al. Multidisciplinary group performance–measuring integration intensity in the context of the North West London Integrated Care Pilot. Int J Integr Care. 2013 doi: 10.5334/ijic.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thompson BM, Levine RE, Kennedy F, et al. Evaluating the quality of learning-team processes in medical education: development and validation of a new measure. Acad Med. 2009;84(10 Suppl):S124–S127. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b38b7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farland MZ, Barlow PB, Lancaster TL, Franks AS. Comparison of answer-until-correct and full-credit assessments in a team-based learning course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(2):Article 21. doi: 10.5688/ajpe79221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lie D, May W, Richter-Lagha R, Forest C, Banzali Y, Lohenry K. Adapting the McMaster-Ottawa scale and developing behavioral anchors for assessing performance in an interprofessional team observed structured clinical encounter. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:266–291. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.26691. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/meo.v20.26691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sigalet E, Donnon T, Cheng A, et al. Development of a team performance scale to assess undergraduate health professionals. Acad Med. 2013;88:989–996. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294fd45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parker K, Jacobson A, McGuire M, Zorzi R, Oandasan I. How to build high quality interprofessional collaboration and education in your hospital: the IP-COMPASS tool. Qual Manag Health Care. 2012;21:1–9. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e31825e87a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stock R, Mahoney E, Carney P. Measuring team development in clinical care settings. Fam Med. 2013;45:691–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tilden V, Eckstrom E, Dieckmann N. Development of the assessment for collaborative environments (ACE-15): a tool to measure perceptions of interprofessional “teamness.”. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:288–294. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1137891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]