Abstract

An accessory spleen (AS) is commonly located near the spleen's hilum and/or in the pancreas tail. However, a symptomatic AS is rarely found in the pelvis. We present a resected case with lower abdominal pain whose final diagnosis was symptomatic AS caused by torsion in the pelvis. An 18-year-old man was presented to our hospital with lower abdominal pain. Enhanced abdominal computed tomography showed an inflammatory mass with a cord-like band in the pelvic space. We finally diagnosed pelvic neoplasm and performed single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) using an access platform. SILS of these tumours located on a pelvic lesion has never been reported; this is the first report of torsion of a pelvic AS. SILS for AS is a safe, feasible procedure, even when the AS lays in the pelvic space.

Keywords: Accessory spleens, single-incision laparoscopic surgery, splenectomy, splenule, splenunculus, supernumerary spleen

An accessory spleen (AS) is commonly located near the spleen's hilum and/or in the pancreas tail. However, a symptomatic AS is rarely found in the pelvis.[1] So, it is difficult to make a correct pre-operative diagnosis of the AS. Herein, we present a resected case of AS caused by torsion in the pelvis.

An 18-year-old man was presented to our hospital with lower abdominal pain. The results of the laboratory investigations were within the normal range except for white blood cell; its level was 13,200/μL with a C-reactive protein level of 14.4 mg/dl. The CA19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen values were within normal limits.

Enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed an inflammatory mass in the pelvic space with a cord-like band between the inflammatory mass and the splenic hilum. That band near the splenic hilum was enhanced, but the other side was not enhanced. A normal spleen was found in its natural place. Finally, we diagnosed benign abdominal tumours and we carried out single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS).

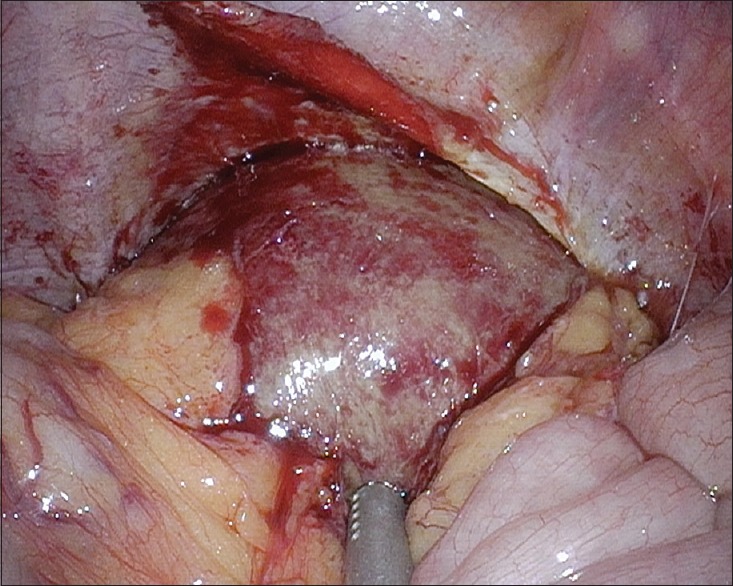

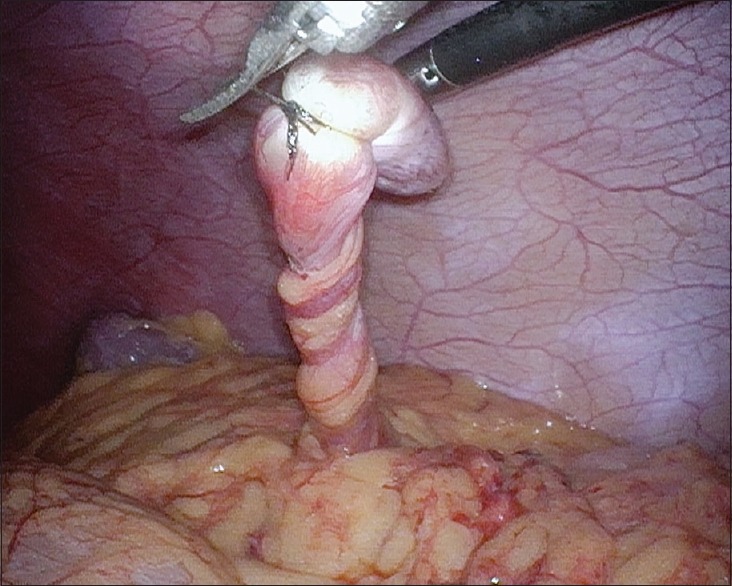

Single-incision laparoscopic surgery with a 2 cm umbilical incision was performed under general anaesthesia using an access platform (GelPOINT Advanced®); during surgery, inspection of the pelvis revealed a solid mass, approximately 6.8 cm in diameter [Figure 1]. Adhesiolysis was performed by blunt rather than sharp dissection techniques. Then, a twisted artery and vein were detected that were tied between the splenic hilum and the tumour. These were resected using ultrasonic devices (Harmonic Ace+ ®) and were double ligated using an intra-abdominal technique [Figure 2]. We extended the 2 cm skin incision to allow removal of the tumor from the umbilical incision without morcellation [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Pelvic accessory spleen

Figure 2.

Twisted structure was composed of the artery and vein

Figure 3.

Resected accessory spleen

The patient had an uneventful post-operative course and was discharged on the 5th post-operative day. Microscopic analyses showed normal splenic components that had fallen into coagulative necrosis, except for the outer serosa. The ‘twisted structure’ was composed of the artery and vein that were occluded by the organised thrombus.

The localisation varies widely, but the most common locations of AS are the splenic hilum (75%) or the pancreas tail (20%).[2] Therefore, the case presented herein is one with a rare localisation of AS, of interest due to its proximity to the rectovesical pouch. Furthermore, torsion of the AS is also uncommon, representing about 0.2%–0.3% of splenectomies.[3,4]

Even with the recent advances in radiological investigations, making a pre-operative diagnosis is difficult. In fact, a pelvic AS is difficult to detect pre-operatively. We could not reach a pre-operative diagnosis that was better than ‘tumour with inflammation unclassifiable as benign or malignant’. Even if we can consider AS as a differential diagnosis pre-operatively, it might be difficult to make a correct diagnosis unless, using a CT scan, we can clearly contrast-enhance and visualise the blood vessels communicating between the splenic vessels and the tumour.

In previously published reports, abdominal surgery has been the most frequently reported method of surgical approach.[5] However, we proceeded to surgery with a strategy, which was to start by staging laparoscopic surgery using the SILS technique and if necessary, switch to conventional laparoscopic surgery or abdominal surgery even if we could not exclude the possibility of a malignant disorder. This was because we knew that we might be able to observe some new information in the abdominal cavity that we might not be able to find by pre-operative diagnostic imaging alone. We also chose this strategy because we could switch the procedure at any time.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Unver Dogan N, Uysal II, Demirci S, Dogan KH, Kolcu G. Accessory spleens at autopsy. Clin Anat. 2011;24:757–62. doi: 10.1002/ca.21146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang KR, Jia HM. Symptomatic accessory spleen. Surgery. 2008;144:476–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mortelé KJ, Mortelé B, Silverman SG. CT features of the accessory spleen. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1653–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hems TE, Bellringer JF. Torsion of an accessory spleen in en elderly patient. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:838–9. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.780.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood TW, Mangelson N. Urological accessory splenic tissue. J Urol. 1987;137:1219–20. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44458-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]