Abstract

Some investigators have postulated a viral cause of malignant glioma, possibly SV40 [Miller G. Brain cancer. A viral link to glioblastoma? Science 2009;323(5910):30–1] or cytomegalovirus (CMV). A source of other brain tumor viruses might be the anopheles mosquito, the vector of malaria. Evidence of an association of anopheles with brain tumors can be found in the relationship between malaria outbreaks in United States and reports of brain tumor incidence by state. There is a significant association between US malaria outbreaks in 2004 and the reports of brain tumor incidence 2000–2004 from 19 US states (p < 0.001). Because increased numbers of both malaria cases and brain tumors could be due solely to the fact that some states, such as New York, have much larger populations than other states, such as North Dakota, multiple linear regression was performed with number of brain tumors as the dependent variable, malaria and population as independent variables. The effect of malaria was significant (p < 0.001), and independent of the effect of population (p < 0.001). Perhaps anopheles transmits an obscure virus that initially causes only a mild transitory illness but much later a brain tumor. If a mosquito-transmitted brain tumor virus could be identified, development of a brain tumor vaccine might be possible.

Introduction

Some investigators have postulated a viral cause of brain tumors, possibly SV40 [1] or cytomegalovirus (CMV) [2]. The CMV-glioblastoma association is controversial. It is unclear why CMV, a common virus, would cause glioblastoma in only a small subset of those infected, especially since in vitro studies have failed to show that CMV transforms normal cells into cancerous cells [3].

Relationship of malaria outbreaks and brain tumors

Another source of brain tumor viruses might be the anopheles mosquito, the vector of malaria. Evidence of an association of anopheles with brain tumors can be found in the relationship between malaria outbreaks in United States [4] and reports of brain tumor incidence by state [5].

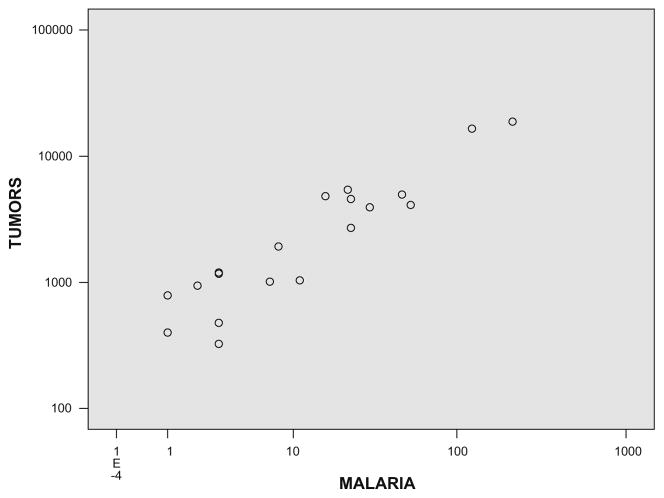

Fig. 1 shows a significant association between US malaria outbreaks in 2004 (data from Fig. 2 of Ref. [4]) and the reports of brain tumor incidence 2000–2004 from 19 US states (data from Table 9 of Ref. [5]). There were also (not shown) highly significant correlations between malaria and malignant brain tumors, as well as malaria and benign brain tumors.

Fig. 1.

Malaria cases in 2004 reported to the Centers for Disease Control versus brain tumors reported to the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (2000–2004) in 19 US states (two states, Maine and Rhode Island, overlap). There is a significant correlation (r = 0.956, p < 0.001).

Because increased numbers of both malaria cases and brain tumors could be due solely to the fact that some states, such as New York, have much larger populations than other states, such as North Dakota, multiple linear regression was performed with number of brain tumors as the dependent variable, malaria and population as independent variables. The effect of malaria was significant (p < 0.001), and independent of the effect of population (p < 0.001).

Hypothesis

Although the anopheles mosquito is mainly known as the vector of malaria, it carries arboviruses, including West Nile Virus and Japanese Encephalitis [6,7]. In addition, anopheles carries o’nyong-nyong virus and chikungunya virus [8]. (Eastern Equine Encephalitis, Western Equine Encephalitis, and St. Louis Encephalitis are arboviruses, their main mode of transmission being the aedes mosquito. There is no relationship of outbreaks of these encephalitides to brain tumors.).

Perhaps anopheles transmits an obscure virus that initially causes only a mild transitory illness but much later a brain tumor. If a mosquito-transmitted brain tumor virus could be identified, development of a brain tumor vaccine might be possible.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Tognon M, Casalone R, Martini F, De MM, Granata P, Minelli E, et al. Large T antigen coding sequences of two DNA tumor viruses, BK and SV40, and nonrandom chromosome changes in two glioblastoma cell lines. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1996;90(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(96)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell DA, Xie W, Schmittling R, Learn C, Friedman A, McLendon RE, et al. Sensitive detection of human cytomegalovirus in tumors and peripheral blood of patients diagnosed with glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10(1):10–8. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller G. Brain cancer. A viral link to glioblastoma? Science. 2009;323(5910):30–1. doi: 10.1126/science.323.5910.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skarbinski J, James EM, Causer LM, Barber AM, Mali S, Nguyen-Dinh P, et al. Malaria surveillance – United States, 2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(4):23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CBTRUS. Statistical report: primary brain tumors in the United States, 2000–2004. Hinsdale, Illinois: Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States; 2008. pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almeida AP, Galao RP, Sousa CA, Novo MT, Parreira R, Pinto J, et al. Potential mosquito vectors of arboviruses in Portugal: species, distribution, abundance and West Nile infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(8):823–32. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thenmozhi V, Rajendran R, Ayanar K, Manavalan R, Tyagi BK. Long-term study of Japanese encephalitis virus infection in Anopheles subpictus in Cuddalore district, Tamil Nadu, South India. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(3):288–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vanlandingham DL, Hong C, Klingler K, Tsetsarkin K, McElroy KL, Powers AM, et al. Differential infectivities of o’nyong-nyong and chikungunya virus isolates in Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72(5):616–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]