Abstract

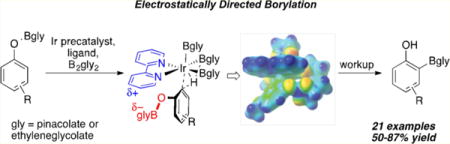

A strategy for affecting ortho versus meta/para selectivity in Ir-catalyzed C–H borylations (CHBs) of phenols is described. From selectivity observations with ArylOBpin (pin = pinacolate), it is hypothesized that an electrostatic interaction between the partial negatively charged OBpin group and the partial positively charged bipyridine ligand of the catalyst favors ortho selectivity. Experimental and computational studies designed to test this hypothesis support it. From further computational work a second generation, in silico designed catalyst emerged, where replacing Bpin with Beg (eg = ethylene glycolate) was predicted to significantly improve ortho selectivity. Experimentally, reactions employing B2eg2 gave ortho selectivities > 99%. Adding triethylamine significantly improved conversions. This ligand– substrate electrostatic interaction provides a unique control element for selective C–H functionalization.

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Catalytic C–H functionalization is a powerful synthetic tool that offers innate synthetic advantages in terms of step, atom, and redox economy, provided that the catalytic functionalization is both active and selective.1 Simultaneously obtaining both high activity and high selectivity, however, can be challenging. It might be supposed that strong catalyst—substrate interactions are best for obtaining selectivity. However, strong interactions can be a death knell for activity. The work of Yu and coworkers, for example, has demonstrated that the involvement of highly stable metallacycle intermediates significantly limits the range of reactive substrates; weak coordination leads to higher reactivity, providing access to a large variety of functionalizations.2,3 Weak interactions can be fully sufficient for selectivity, since a ΔΔG‡ of 2.7 kcal·mol−1 is sufficient for 99:1 selectivity at 25 °C.

C–H functionalizations using noncovalent direction for uncharged substrates have been identified in hydrophobic—hydrophobic interactions between cyclodextrins and steroids in C–H hydroxylations,4–7 host–guest size-differentiated C–H activations,8,9 and hydrogen bond directed C–H functionalizations.10–14 Hydrogen bonding has also proven effective in directing the hydroformylation of alkenes15,16 and the hydrometalation of unsymmetrical alkynes.17,18 Recently, significant progress has been made in demonstrating the viability of anion–π interactions for directing catalysis,19,20 though experimental quantification of these interactions is challenging.21 The importance of noncovalent interactions is routinely seen in organocatalysis and biological systems.22,23

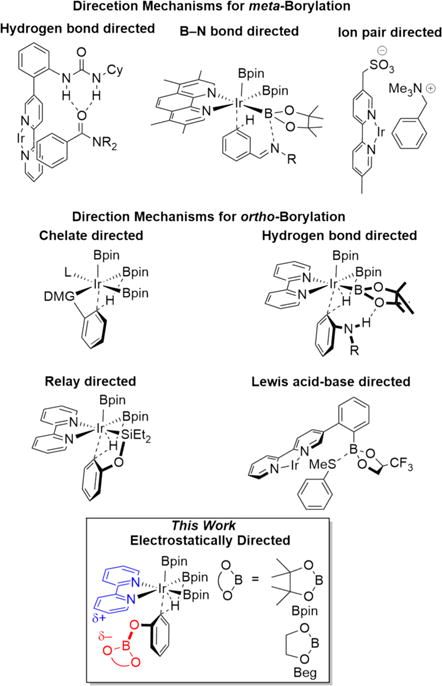

The regioselectivity of metal catalyzed C–H borylations (CHBs) of the sp2-hybridized C–H bonds in arenes is usually sterically determined.24 To complement this selectivity, the direction of CHBs toward sterically encumbered positions has been of great interest.25–27 The most common approach makes use of strong substrate-catalyst interactions, particularly chelation of a directed metalating group (DMG) to the metal center to achieve ortho-borylation (Scheme 1). This has been accomplished using surface supported phosphines,28 certain monodentate ligands,29 hemilabile bidentate ligands,30 and P,Si-, N,Si-, and N,B-bidentate anionic ligands.31,32 Alternative approaches to ortho-borylation shown in Scheme 1 include relay direction with silanes,33 which is also useful in directed C–H silylations.34,35

Scheme 1.

Selected Mechanisms for Directed Borylation

Weaker interactions have been exploited in CHBs as well. For example, the N–H protons in aniline carbamates can hydrogen bond to the oxygen atoms of Bpin ligands, favoring ortho-borylation. Similar interactions were exploited in traceless ortho-borylations of anilines and aminopyridines.36,37 Recently, meta-selective borylations of imines have been proposed to proceed via a related outer-sphere mechanism.38 These hydrogen bonding concepts have been extended to meta-selective CHBs where pendant ureas on dipyridyl ligands function as dual hydrogen bond donors (Scheme 1).39

Kanai and co-workers described ortho-borylation of aryl thioethers directed by a Lewis acid–base interaction between the thiol ether in the substrate and a boron glycolate linked to the bipyridine ligand.40,41 Interestingly, high meta selectivity was achieved only for glycolates bearing trifluoromethyl groups. Both Kanai and Phipps’ recent approaches rely on interactions between pendant groups on the bipyridine ligand with matching functionality in the substrate to direct CHB to the desired site.

While extending traceless protection chemistry to phenols, where the OH group would be converted to OBpin prior to C–H borylation, enhanced ortho-borylation was observed. In this paper, experimental and computational results implicate a subtle electrostatic attraction between O-Bglycolate and bipyridyl groups as the origin for ortho direction (Scheme 1). Calculated stabilizations of ortho transition states were sensitive to the steric nature of the boryl ligand; thus, greatly enhanced selectivities resulted by redesigning the diboron reagent.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

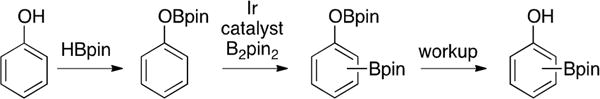

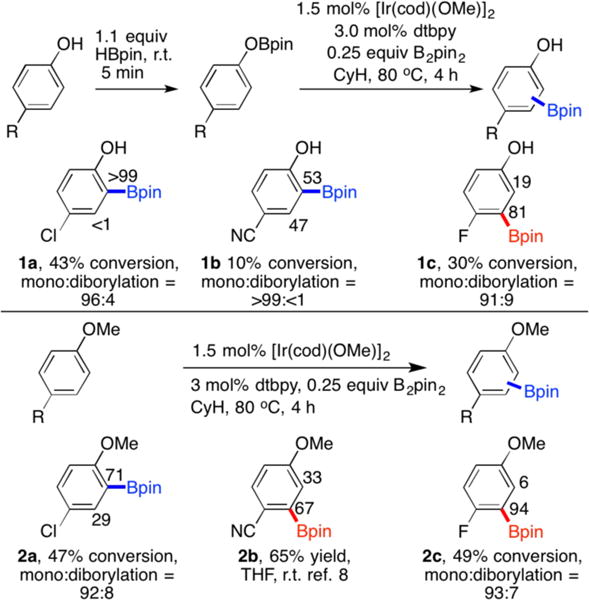

We first examined the borylation of phenol with two equivalents of HBpin, expecting that C6H5OBpin would form rapidly, and the ensuing borylation of this intermediate would afford a mixture of m- and p-HOC6H4Bpin upon workup (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Phenol Borylation with Traceless Protection

Using the commonly employed ligand/precatalyst combination dtbpy/[Ir(OMe) (cod)]2 (dtbpy = 4,4′-tert-butyl-2,2′-bipyridine, cod = 1,5-cyclooctadiene),42 a striking amount of ortho-borylation was found (o:m + p = 15:85). This was surprising since anisole affords only 4% of the ortho-borylation product and an OBpin group is sterically larger than an OMe group.

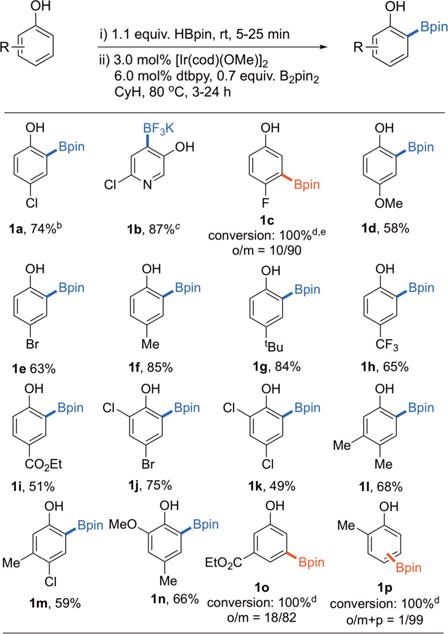

The propensity for borylation ortho to OBpin was more apparent in comparisons between 4-substituted phenols and 4-substituted anisoles. Chart 1 clearly shows that borylation ortho to OBpin relative to OMe is preferred.43 Borylation of 4-chlorophenol was highly ortho selective, while the CHB for 4-cyanophenol was not. However, CHB ortho to OBin was more pronounced than CHB ortho to OMe in 4-cyanoanisole, where borylation ortho to CN is preferred. Borylation ortho to F predominated for both 4-fluoro substrates, although borylation ortho to OBpin increased slightly. With these results in hand, CHB for a range of phenols was surveyed. The results are shown in Table 1.

Chart 1.

C–H Borylation of 4-Substituted Phenols and Anisoles

Table 1.

Ortho Borylation of Substituted Phenols with B2pin2a

|

For details, see the SI; yields are isolated.

Entry 1a was obtained in 74% yield on a 2 g scale using 1.5 mol % Ir-catalyst, 3.0 mol % dtbpy, and 0.7 equiv of B2pin2.

The Bpin product was converted to the BF3K salt for isolation.

Conversion and isomer ratio based on GC-FID.

Approximately 18% diborylated product was observed.

The yields for the products in Table 1 range from excellent to moderate. This process is operationally simpler than the relay-directed approach highlighted in Scheme 1,33,44 as the relay directed approach requires (i) catalyzed O–silylation of the phenol with Et2SiH2 to generate ArOSiEt2H, (ii) conversion of Bpin intermediates to BF3K salts, and (iii) removal of the O–SiEt2H directing groups affording high yields of pure BF3K phenols. The Bpin to BF3K conversion was required because protodeborylation45 of C-Bpin occurred when Si–O cleavage of Bpin products were attempted.

The loadings in Table 1 are higher than we normally employ because the reactions were run at small scale with weighed amounts of catalyst (see the Supporting Information (SI) for details). To test for scalability at lower catalyst loadings, compound 1a was prepared from 2.0 g of 4-chorophenol, 1.1 equiv of HBpin, and 0.7 equiv of B2pin2, using 1.5 mol % [Ir(OMe)(cod)]2 and 3 mol % dtbpy. After workup, 2.9 g (74% yield) of 1a was isolated as a colorless solid.

With the exception of products 1c, 1o, and 1p, ortho selectivity is high (>99%) and is not degraded by substitution ortho to OH. However, the substrates in Table 1 where high selectivity is observed have substituents at the 4-position that are larger than CN or F. This indicates that the unusual OBpin directing effect is not strong enough to overcome standard steric control. While the traceless CHB transformation in Table 1 is simpler than Hartwig’s relay-directed ortho CHBs of phenols, the ortho selectivity for their protocol was high for all substrates, including phenol. This motivated us to better identify features that contribute to the selectivities in the traceless reaction. The reaction of 4-methoxyphenol is particularly perplexing because the catalyst exclusively selects the position ortho to OBpin yielding 1d when given a choice of CHB ortho to the smaller OMe substituent. To gain further insight into this unusual directing effect, we turned to theory.

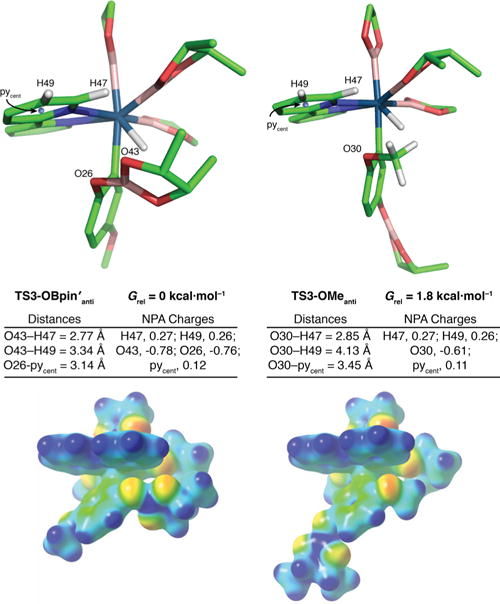

Our initial computational model substrate was 4-MeO-C6H4OBpin′ (3), where pin′ = meso-butylene glycolate. The OBpin′ model was chosen because its methyl groups can partially reflect the steric interactions present in the full catalytic system. A series of transition structures for the borylation of 3 with (bpy)Ir(Beg)2(Bpin′) were located in M06 calculations employing an SDD basis set on Ir and a 6–31G* basis set on the other atoms. The lowest-energy structures for borylation ortho to OBpin′ (TS3-OBpin′anti) and ortho to OMe (TS3-OMeanti) are shown in Figure 1. The “anti” designation in these structures refers to the arrangement of the methyl or Bpin′ groups relative to the bpy ligand; a structure with the Bpin′ syn to the bpy (TS3-OBpin′syn, see the SI) was higher in energy. A striking observation was that TS3-OBpin′anti is enthalpically favored over TS3-OMeanti by 5.2 kcal·mol−1. The steric interaction of the two pin′ groups in TS3-OBpin′anti restricts their motion, so that TS3-OMeanti is entropically favored, but TS3-OBpin′anti remains favored in free-energy by 1.8 kcal·mol−1. From the model, the isomer ratio is predicted to be 92:8, favoring 1d. Since the minor isomer is not experimentally detected in borylation of 4-methoxyphenol, the model underestimates Grel for TS3-OMe.

Figure 1.

Transition state structures, and their calculated electrostatic potential surfaces, for borylation of 4-MeO-C6H4OBpin′ with (bpy)Ir(Beg)2(Bpin′).

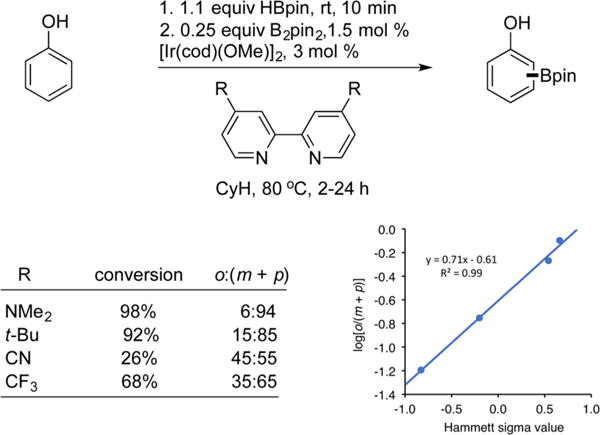

We sought to identify the structural effect responsible for the stunning enthalpic preference for TS3-OBpin′anti over TS3-OMeanti. An unusual feature of both structures is a rotation of the OBpin′ or OMe groups out of the plane of the aromatic ring when ortho to the C–H insertion. The B27–O26–Cipso–Ca and the CMe–O30–Cipso–Ca dihedral angles in TS3-OBpin′anti and TS3-OMeanti are ≈90°. This rotation is not present in the ground state of 4-MeO-C6H4OBpin′ nor when the OBpin or OMe groups are meta to the C–H insertion. In the orthogonal orientations, the dipoles associated with the B27–O26–Cipso, B27–O43–C, and CMe–O30–Cipso angles are oriented toward the proximal bpy pyridine ring, suggesting an electrostatic interaction. To assess the role of this electrostatic interaction in the selectivity, the NPA (Natural Population Analysis) charges were calculated with selected values given in Figure 1 (see SI for full listing). The NPA charges on O43 and O26 in TS3-OBpin′anti are significantly more negative than O30 in TS3-OMeanti, and O43 has the shortest contacts to H47 and H49, which are partially positively charged. Electrostatic potential maps were calculated and are shown in Figure 1. From the maps, O43 is best positioned to maximize attraction to the positive charge of H47 and H49, while it is expected that O26 and O30 offer similar degrees of electrostatic stabilization to their respective transition states. In Figure 1, the sum of all charges on C, H, and N on the pyridine ring closest OBpin′ and OMe in the two TSs are 0.12 and 0.11, respectively. A crude electrostatic model can be constructed for TS3-OBpin′anti and TS3-OMe where the charge on the pyridine ring for both transition states is approximated as a point charge at its centroid, pycent. For OBpin’, a charge corresponding to the sum of B and its surrounding O atoms is placed at B. For TS3-OMeanti, the OMe is simply represented by the charge on O. These models predict ~3 kcal·mol−1 stabilization of TS3-OBpin′anti over TS3-OMe, which would be sufficient for the observed selectivity. The O26–pycent distance in TS3-OBpin′anti is 0.31 Å shorter than the O30–pycent distance in TS3-OMe. If the electrostatic model is correct, electronic alteration of the bipyridine ligand should affect selectivities. To test this, borylations of phenol were performed with 4,4′-substituted bipyridines 4a–d. As shown in Chart 2, there is a clear trend for increasing ortho selectivity as the bipyridine ligand is made more electron deficient. Moreover, plots of log10[o/(m + p)] vs the Hammett parameters of the 4,4′ substituents on the bipyridine ligands are linear and have a positive slope (Chart 2).

Chart 2.

Ligand Effects on Borylation Selectivity

Although this provides experimental evidence to the proposed electrostatic interactions, the improved ortho selectivity for 4d comes at the expense of catalytic activity.42 Thus, we sought another solution for improving borylation selectivities that provided synthetically useful reactivity and selectivity for substrates like 4-fluorophenol.

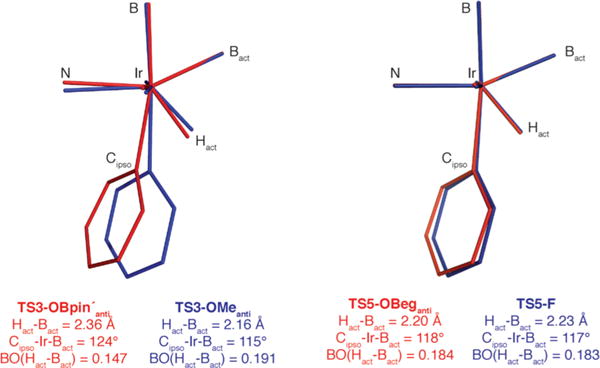

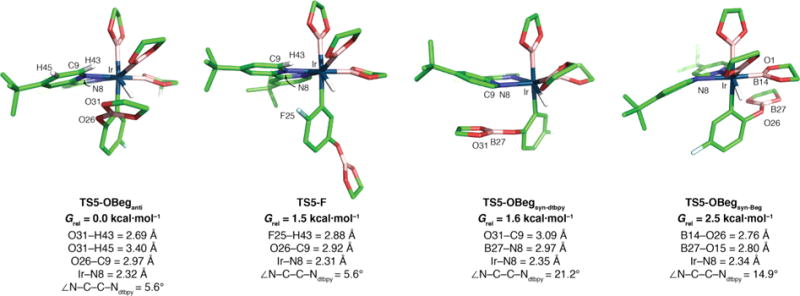

A closer inspection of the calculated TSs revealed significant distortions of the arene geometries for TS3-OBpin′anti and TS3-OMeanti (Figure 2). Specifically, steric pressure from the Bpin′ groups pushes the arene away from the activating Beg group in TS3-OBpin′anti. This results in elongation of Hact…Bact in TS3-OBpin′anti (2.360 Å) relative to TS3-OMeanti (2.159 Å), which translates to a 23% reduction in the natural bond order between Hact and Bact. Since Beg is the smallest glycolatoboryl ligand, we hypothesized that transition states with Beg ligands should be less distorted, allowing for TS stabilization by removing the steric clash between Bpin groups, which simultaneously would allow for maximum TS stabilization from Hact …Bact interactions. To test this hypothesis, 4-F-C6H4OBeg was chosen to assess borylation ortho to OBeg or F, which is the smallest non-hydrogen substituent. TSs for borylation ortho to F (TS5-F) and ortho to OBeg (TS5-OBeganti) were calculated and are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Calculated inner coordination spheres, selected metrical parameters, and natural bond orders for TS3-OBpin′anti and TS3-OMeanti (left) and TS5-OBeganti and TS5-F (right).

Figure 3.

Transition states for borylation of 4-F-C6H4OBeg with (dtbpy)Ir(Beg)3.

The geometries of the inner coordination sphere for borylation ortho to OBeg or F are nearly identical as seen by the equivalent Cipso–Ir–Bact angles for TS5-OBeganti and TS5-F (Figure 2). This indicates that the reduced repulsion between Beg groups restores the Hact·· Bact interaction in TS5-OBeganti. Further, TS5-OBeganti has short contacts between O31–H43 and O31–H54 (Figure 3). The OBeg B to pyridine centroid distance in TS5-OBeganti is 0.3 Å shorter than the corresponding distance in TS3-OBpin′anti, thus increasing the strength of the electrostatic interaction and further stabilizing TS5-OBeganti. Interestingly, TS5-OBegsyn, where the OBeg is directly below a pyridine ring in the dtbpy ligand, is 1.6 kcal·mol−1 above the anti configuration. We attribute this to the significant distortion of the bipyridine ligand which is seen in the 22.2° dihedral between the dtbpy nitrogens compared to the 5.6° dihedral in TS5-OBeganti. This twisting of the dtbpy ligand results in a small elongation of the Ir–N bond (0.03 Å), but more importantly, N8 has poorer overlap with the Ir center. Stabilizing Lewis acid/base interactions between a boryl ligand and the substrate were considered as well.

There is a distance of 3.22 Å between an O of Bact and B of the OBeg group in TS5-OBeganti. The energy of this interaction is below the 0.05 kcal·mol−1 threshold for second order perturbation theory analysis of the Fock matrix in the NBO basis. Although a TS was located (Figure 3, TS5-OBegsyn‑Beg) with a short B…O contact, 2.76 Å, between O26 in the OBeg group and B14 in a spectator boryl ligand, it lies 2.3 kcal·mol−1 above TS5-OBeganti. Despite searching, no Lewis acid/base interaction could be found which provided a lower TS than TS5-OBeganti. Overall, TS5-OBeganti is favored over TS5-F by 1.5 kcal·mol−1, which is due to OBeg…dtbpy electrostatic interactions. This corresponds to a 93:7 isomer ratio favoring borylation ortho to OBeg at 25 °C.

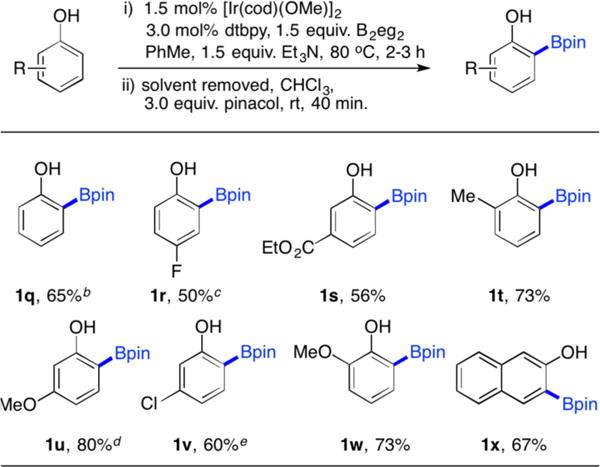

We tested the computational prediction by preparing B2eg2 from B2(OH)4 and ethylene glycol (see the SI for details). The room temperature rates were too slow for direct comparison to the computational “conditions,” so CHBs were performed at 80 °C (Table 2). The Beg products were converted to pinacolate esters, which were easier to purify. Most importantly, CHB with B2eg2 as the boron source provided exclusively ortho-borylated products. Such exclusive regiochemical outcomes, validated the theoretically driven decision to employ B2eg2 in these reactions. That said, we were not disappointed by the fact that that the experimentally observed ortho-borylation of 4-fluorophenol (1r) was higher than that predicted by theory.

Table 2.

ortho-Borylation of Phenols with B2eg2a

|

For details, see the SI. Yields are isolated monoborylated products. Diborylated products were not isolated.

Mono:o,o′-diborylation = 82:18.

B2eg2 used as 1.2 equiv, mono:o,o′-diborylation = 89:11.

Mono:o,o′-diborylation = 81:19.

Mono:o,o′-diborylation = 85:15.

Diborylated side products were observed for some of the substrates, but were readily separable by chromatography. Given the previously reported difficulties in isolating ortho-borylated phenols, the yields here of pure products are highly satisfactory. Remarkably, toluene was an excellent solvent for the reactions, as competing solvent borylation was not observed.

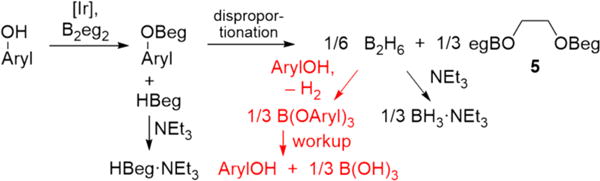

In addition to a change in the boron sources, the Table 2 conditions includes the addition of triethylamine, without which CHB conversions for all phenols plateaued at 50%. Unlike HBpin, which is the most stable HBgly (gly = glycolate) compound, HBeg rapidly disproportionates at room temperature to B2H6 and B2eg3 (Scheme 3). However, Shore showed that HBeg reacts with NMe3 to afford HBeg·NMe3 which is stable at room temperature.46,47

Scheme 3.

Minimizing B(OAryl)3 Formation

Our initial hypothesis was that HBeg generated during the formation of ArylOBeg rapidly disproportionated, and the B2H6 produced converted free ArylOH to B(OAryl)3 and H2, as shown in red in Scheme 3. Aryl borates rapidly hydrolyze to phenols and boric acid upon workup, which would account for the recovery of unreacted phenols (Scheme 3). It is noteworthy that XBeg compounds (X = halogen) are not stable. They associate in solution, which has been attributed to Lewis acid-interactions.48 Acid-catalyzed side reactions of B2H6 or HBeg could be deleterious. If this is the case, triethylamine could trap these reactive species as their NEt3 adducts before they wreak havoc on the desired borylation pathway (Scheme 3). Given the instability of HBeg, its addition to phenols to form ArylOBeg species is not synthetically applicable. Thus, an important question is: Are ArylOBeg intermediates formed in the reaction?

Owing to the stability of HBpin, we generate ArylOBpin and clearly demonstrate they are competent in the B2pin2 ortho CHBs of phenols (Table 1). However, we wished to show that ArylOBpin species form without the addition of pinacolborane. To demonstrate this, [Ir(dtbpy) (COE) (Bpin)3] (COE = cyclooctene) in cyclohexane-d12 was added to 4-FC6H4OH which provided quantitative conversion to 4-FC6H4OBpin by 19F, 11B and 1H NMR. Proton resonances closely matching previously reported [Ir(dtbpy)(H) (Bpin)2(COE)] were also observed.49 This shows that even without pinacolborane ArylOBpin species form under the reaction conditions. Thus, indicating that HBpin pregeneration of ArylOBpin is unnecessary; however, it should be noted that an extra equivalent of boron is needed as the first borylaiton will occur at the phenolic hydrogen. More pertinent to the original question, this data provides support that ArylOBeg species form without HBeg addition because borylations with B2eg2 proceed through a similar trisboryl species, [Ir(dtbpy)Beg3].

To conclusively determine if the ArylOBeg species forms and assess whether formation of B(OAryl)3 led to the low conversions, we prepared 2-F-C6H4OBeg from 2-fluorophenol and ClBeg, according to Lappert’s procedure.50 The resonance at δ 22.9 in the 11B{1H} NMR spectrum of the product is typical for B(OR)3 species. However, 11B NMR is not well-suited for quantifying how many B(OR)3 species are present. In contrast, 19F is an s = 1/2 nucleus with a broad NMR spectral window. As such, by employing a fluorinated phenol as our substrate we could use 19F NMR to determine the number of B(OR)3 species.

In practice the 19F resonance (δ – 132.6) in the 19F{1H} spectrum prepared by Lappert’s route was relatively broad (22 Hz at half-maximum) and low levels of impurities were observed. Given that Lappert’s synthesis eliminates HCl we were concerned that these impurities could deactivate the CHB catalyst and/or catalyze detrimental side-reactions. Thus, we sought an alternative means for generating ArylOBeg species.

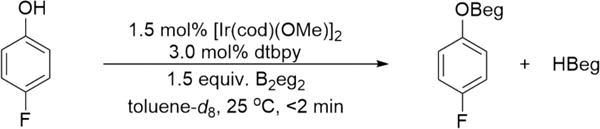

Based on our previous result with the isolated trisboryl catalyst and the fact that iridium is known to readily form Ir–Bgly species, we theorized that [Ir(cod) (OMe)]2 could catalyze the formation of ArylOBeg with B2eg2 and phenol. Excitingly, full conversion to 2-FC6H4OBeg was achieved with 1 mol % [Ir(cod) (OMe)]2 and B2eg2.

With a facile route to ArylOBeg species, 4-FC6H4OBeg was generated and spectra were collected. To test if this species is formed under the reaction conditions 4-fluorophenol was added to an NMR tube containing a toluene-d8 solution of B2eg2, [Ir(OMe) (cod)]2, and dtbpy (Scheme 4). As judged by 19F NMR, this resulted in rapid, quantitative conversion to 4-F-C6H4OBeg at room temperature. Interestingly, the 11B NMR spectrum displayed a doublet at 28.9 ppm, but this doublet collapsed in the 11B{1H} spectrum. This is consistent with generation of HBeg. Ultimately, these experiments confirmed two key pieces of information: (i) ArylOBeg species are rapidly formed under the reaction conditions and (ii) diborane does not consume phenol substrates as we had originally hypothesized. As B2eg3 (5) and B2H6, the disproportionation products from HBeg, are not known to be active for CHB, we propose amine stabilized HBeg participates in Ir-catalyzed borylation.

Scheme 4.

NMR Tube Reaction Showing ArylOBeg Species

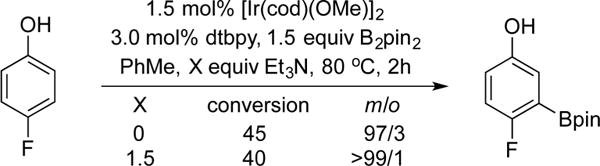

Although our experiments supported the role of triethylamine as an HBeg stabilizer, we recognize that the change in conditions between Tables 1 and 2 may also affect the selectivities. As a control, the borylation of 4-fluorophenol with B2pin2 as the boron source was carried out in toluene with and without triethylamine (Chart 3). In toluene without triethylamine, the meta product was more pronounced (m/o = 97:3) than that observed in cyclohexane (m/o = 90:10).

Chart 3.

Control Experiments with B2pin2

Given that the addition of triethylamine actually pushed the reaction toward the meta product, the selectivities in Table 2 must solely be due to the change in the boron source and not a change in the conditions (i.e., solvent or additives).

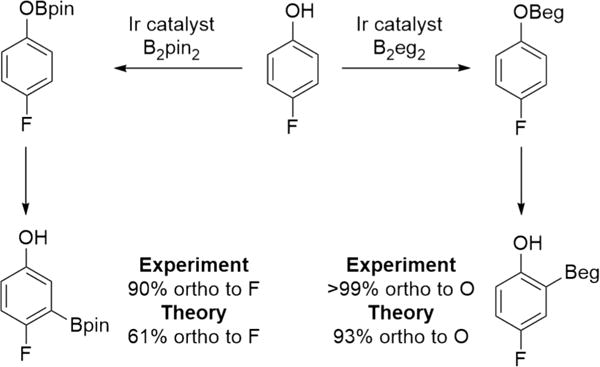

B2eg2 was critical to the high ortho selectivity as selectivities for some substrates in Table 2 with B2pin2 were poor. The directing difference between Bpin and Beg is best illustrated by the selectivity for 4-fluorophenol where borylation with B2pin2 gives a 9:1 ratio favoring borylation ortho to F, while B2eg2 gives exclusive borylation ortho to O (Scheme 5). Theory predicts the same trend.

Scheme 5.

Boron Reagent Effects on Borylation of 4-Fluorophenol

It is important to recognize that disentangling the directing effect of substituents on the phenols and the electrostatic interactions proposed herein is challenging. However, the borylation of phenol itself is instructional as phenol bears no other substituent to affect regiochemical outcomes, and it is a substrate where the calculated electrostatic interaction should be maximized. Yet, borylation with B2eg2 provided only ortho-borylated products (1q), whereas with B2pin2 a ratio of 15:85 (o:m + p) was observed.

Finally, electrostatic interactions with delocalized π-systems are well established. In most examples the π-system interacts with a positively charge partner.51 Nevertheless, anion interactions and electron deficient π-systems can be stabilizing.21,52 Moreover, in neutral pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid dimers, the interaction of the electron-rich carboxylic acid group of one pyridine with the electron-deficient pyridine π-system of its partner, is stabilizing by −7.3 kcal·mol−1.53 This further supports our hypothesis that electrostatic interactions dictate the regioselectivity observed experimentally and supported by computational studies.

CONCLUSIONS

To summarize, iridium-catalyzed ortho directed borylation of phenols using the most commonly employed ligand/precatalyst combination dtbpy/[Ir(OMe) (cod)]2 is reported. After traceless protection of phenols with Bpin, CHB ortho to OBpin occurred in a higher than expected portion. This phenomenon was explored in various phenol substrates which showed the requirement for a substrate larger than fluorine in the 4-position for good ortho selectivity. To further understand the origins of this ortho selectivity, we turned to calculations which revealed an electrostatic interaction between the partially positive bipyridine ligand and partially negative OBpin in the substrate. Seeking experimental evidence for this calculated interaction, electron rich through electron poor bipyridine ligands were used in the borylation of phenol. Electron poor ligands produced higher ortho selectivity thus supporting the calculations; however, the electron poor ligands provided low reactivity. Further study of the calculations suggested that a steric interaction from the methyl groups on the OBpin species distorted the transition state geometries, but by changing to OBeg these geometries significantly restored. Thus, borylations with B2eg2 were conducted and high ortho selectivity was achieved. Overall, by simply changing the boron source, high ortho selectivity was achieved which we attribute to a unique electrostatic interaction between the bipyridine ligand and OBeg group. While the interactions revealed here are fortuitous, the demonstration that they can be both sterically and electronically modulated augurs favorably for deploying them in specifically designed catalysts. Efforts toward this end are underway in our laboratories.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (GM63188) and BoroPharm, Inc. for supplying B2pin2 and B2(OH)4.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b02232.

Full characterization, copies of all spectral data, experimental procedures, and coordinates of computed transition states (PDF)

ORCID

Buddhadeb Chattopadhyay: 0000-0001-8473-2695

Daniel A. Singleton: 0000-0003-3656-1339

Milton R. Smith III: 0000-0002-8036-4503

Notes

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): R.E.M. and M.R.S. acknowledge a financial interest in BoroPharm, Inc.

References

- 1.Gutekunst WR, Baran PS. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40(4):1976. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engle KM, Mei T-S, Wasa M, Yu J-Q. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45(6):788. doi: 10.1021/ar200185g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li G, Wan L, Zhang G, Leow D, Spangler J, Yu J-Q. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(13):4391. doi: 10.1021/ja5126897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslow R, Zhang X, Huang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119(19):4535. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslow R, Huang Y, Zhang X, Yang J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(21):11156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang J, Breslow R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39(15):2692. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000804)39:15<2692::aid-anie2692>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J, Gabriele B, Belvedere S, Huang Y, Breslow R. J Org Chem. 2002;67(15):5057. doi: 10.1021/jo020174u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung DH, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(30):9781. doi: 10.1021/ja061412w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown CJ, Toste FD, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. Chem Rev. 2015;115(9):3012. doi: 10.1021/cr4001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S, Incarvito CD, Crabtree RH, Brudvig GW. Science. 2006;312(5782):1941. doi: 10.1126/science.1127899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das S, Brudvig GW, Crabtree RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(5):1628. doi: 10.1021/ja076039m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dydio P, Reek JNH. Chem Sci. 2014;5(6):2135. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis HJ, Phipps RJ. Chem Sci. 2017;8(2):864. doi: 10.1039/c6sc04157d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butts CP, Filali E, Lloyd-Jones GC, Norrby P-O, Sale DA, Schramm Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(29):9945. doi: 10.1021/ja8099757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Šmejkal T, Breit B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47(2):311. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dydio P, Dzik WI, Lutz M, de Bruin B, Reek JNH. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(2):396. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rummelt SM, Fürstner A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53(14):3626. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rummelt SM, Radkowski K, Roşca D-A, Fürstner A. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(16):5506. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao Y, Domoto Y, Orentas E, Beuchat C, Emery D, Mareda J, Sakai N, Matile S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(38):9940. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y, Cotelle Y, Sakai N, Matile S. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(13):4270. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giese M, Albrecht M, Rissanen K. Chem Commun. 2016;52(9):1778. doi: 10.1039/c5cc09072e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler SE, Seguin TJ, Guan Y, Doney AC. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49(5):1061. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persch E, Dumele O, Diederich F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54(11):3290. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mkhalid IAI, Barnard JH, Marder TB, Murphy JM, Hartwig JF. Chem Rev. 2010;110(2):890. doi: 10.1021/cr900206p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ros A, Fernández R, Lassaletta JM. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43(10):3229. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60418g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito Y, Segawa Y, Itami K. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(15):5193. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haines BE, Saito Y, Segawa Y, Itami K, Musaev DG. ACS Catal. 2016;6(11):7536. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawamorita S, Ohmiya H, Hara K, Fukuoka A, Sawamura M. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(14):5058. doi: 10.1021/ja9008419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishiyama T, Isou H, Kikuchi T, Miyaura N. Chem Commun. 2010;46(1):159. doi: 10.1039/b910298a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ros A, Estepa B, López-Rodríguez R, Álvarez E, Fernández R, Lassaletta JM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(49):11724. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghaffari B, Preshlock SM, Plattner DL, Staples RJ, Maligres PE, Krska SW, Maleczka RE, Jr, Smith MR., 3rd J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(41):14345. doi: 10.1021/ja506229s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G, Liu L, Wang H, Ding Y-S, Zhou J, Mao S, Li P. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(1):91. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boebel TA, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(24):7534. doi: 10.1021/ja8015878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghavtadze N, Melkonyan FS, Gulevich AV, Huang C, Gevorgyan V. Nat Chem. 2014;6(2):122. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmons EM, Hartwig JF. Nature. 2012;483(7387):70. doi: 10.1038/nature10785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roosen PC, Kallepalli VA, Chattopadhyay B, Singleton DA, Maleczka RE, Smith MR. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(28):11350. doi: 10.1021/ja303443m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preshlock SM, Plattner DL, Maligres PE, Krska SW, Maleczka RE, Smith MR. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(49):12915. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bisht R, Chattopadhyay B. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(1):84. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuninobu Y, Ida H, Nishi M, Kanai M. Nat Chem. 2015;7(9):712. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis HJ, Mihai MT, Phipps RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(39):12759. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li HL, Kuninobu Y, Kanai M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(6):1495. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishiyama T, Takagi J, Hartwig JF, Miyaura N. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41(16):3056. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020816)41:16<3056::AID-ANIE3056>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chotana GA, Rak MA, Smith MR. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(30):10539. doi: 10.1021/ja0428309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamazaki K, Kawamorita S, Ohmiya H, Sawamura M. Org Lett. 2010;12(18):3978. doi: 10.1021/ol101493m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox PA, Leach AG, Campbell AD, Lloyd-Jones GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(29):9145. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b03283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose SH, Shore SG. Inorg Chem. 1962;1(4):744. [Google Scholar]

- 47.McAchran GE, Shore SG. Inorg Chem. 1966;5(11):2044. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shore SG, Crist JL, Lockman B, Long JR, Coon AD. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1972;(11):1123. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boller TM, Murphy JM, Hapke M, Ishiyama T, Miyaura N, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(41):14263. doi: 10.1021/ja053433g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blau JA, Gerrard W, Lappert MF. J Chem Soc. 1957;4116 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salonen LM, Ellermann M, Diederich F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(21):4808. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gamez P, Mooibroek TJ, Teat SJ, Reedijk J. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40(6):435. doi: 10.1021/ar7000099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mirzaei M, Eshtiagh-Hosseini H, Karrabi Z, Molčanov K, Eydizadeh E, Mague JT, Bauzá A, Frontera A. CrystEngComm. 2014;16(24):5352. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.