Abstract

Primary familial brain calcification (PFBC) is a rare neuropsychiatric disorder with characteristic symmetrical brain calcifications. Patients with PFBC may have a variety of symptoms, although they also may be clinically asymptomatic. Parkinsonism is one of the most common movement disorders; however, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. This condition is typically transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion. To date, mutations in SLC20A2, PDGFRB, PDGFB, and XPR1 have been reported to cause PFBC. The aim of the study was to identify the genetic cause of brain calcification in probands from three PFBC families and in 8 sporadic patients and to perform clinical and radiological assessments focusing on parkinsonism in mutation carriers. Three familial PFBC probands and their relatives and eight sporadic patients affected with brain calcifications were enrolled in this study. Whole-exome sequencing identified three novel mutations: c.269G > T, p.(Gly90Val) and c.516+1G > A in SLC20A2 in familial cases, and c.602-1G > T in PDGFB in a sporadic patient. The c.516+1G > A mutation resulted in exon 4 skipping in SLC20A2 (p.Val144Glyfs*85). Dopamine transporter single photon emission computed tomography using 123I-ioflupane and 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine cardiac scintigraphy revealed pre-synaptic dopaminergic deficit and cardiac sympathetic nerve dysfunction in two SLC20A2-related PFBC patients with parkinsonism.

Introduction

Primary familial brain calcification (PFBC), also known as Fahr’s disease or idiopathic basal ganglia calcification, is a rare neuropsychiatric disorder1. In this disease, most symmetrical calcification occurs in the basal ganglia and other brain regions, including the dentate nuclei, thalami, brainstem, supratentorial white matter, and cerebral cortex, in particular within the occipital lobe. Clinical presentation is characterized by psychiatric signs, cognitive impairment, and movement disorders including chorea, dystonia, athetosis, and parkinsonism. Cerebellar and pyramidal signs, seizures, and headache are also associated with this condition. However, individuals with brain calcification can be clinically asymptomatic2–4. This condition is typically transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion and is genetically heterogeneous5. To date, mutations in SLC20A2, PDGFRB, PDGFB, and XPR1 have been reported to be responsible for PFBC and have been detected in both familial and sporadic cases6–9. Nevertheless, these four disease-causing genes do not account for all cases of PFBC, indicating additional genetic heterogeneity. Although true sporadic cases resulting from de novo mutations have been reported10,11, the majority of seemingly sporadic presentations are thought to be due to an inadequate analysis of asymptomatic family members2,12. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) is becoming widely adopted as an efficient strategy to identify disease-causing mutations in genetically heterogeneous diseases. We report here three novel mutations in SLC20A2 and PDGFB responsible for PFBC that were successfully detected using WES. Parkinsonism is one of the most common PFBC-related movement disorders. Although pre-synaptic nigrostriatal dopaminergic dysfunction seems to be involved in the mechanism of PFBC-related parkinsonism13–16, the relationship between PFBC and Lewy body pathology remains controversial17–19. To elucidate the underlying mechanism of PFBC-related parkinsonism, we performed radiological assessments focusing on parkinsonism. In addition to dopamine transporter single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) using 123I-ioflupane, we examined 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy that is useful to differentiate Lewy body-related disorders from other neurodegenerative disorders in genetically confirmed PFBC patients with parkinsonism20–23.

Results

In this study, we identified three novel mutations responsible for PFBC in two familial cases and one sporadic case. Clinical features and genetic findings of genetically confirmed PFBC patients are summarized in Table 1. On the other hand, we could not identify the causative mutation in the remaining subjects (one familial and seven sporadic cases). Clinical and radiological data of the patients who were negatively screened for the candidate genes are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The mutation detection strategy is summarized in Supplementary Table 2 (Materials and Methods).

Table 1.

Clinical and genetic features of genetically confirmed primary familial brain calcification patients in this study.

| Family 1 | Family 2 | sporadic case 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I:2 | II:2 | III:2 | I:1 | II:1 | ||

| sex/age | F/89 | M/62 | M/27 | M/79 | M/52 | F/50 |

| symptom | parkinsonism | parkinsonism | asymptomatic | dementia/parkinsonism | depression | depression |

| MIBG scinti | NE | decreased | NE | decreased | normal | NE |

| DAT SPECT | NE | decreased | NE | decreased | normal | NE |

| causative gene | SLC20A2 | SLC20A2 | PDGFB | |||

| mutation | c.516+1G > A, r.431_516del, p.Val144Glyfs*85 | c.269G > T, p.(Gly90Val) | c.602-1G > T, p.? | |||

| SIFT | not applicable | probably damaging | not applicable | |||

| PolyPhen-2 | not applicable | deleterious | not applicable | |||

| CADD phred-like score | 21.7 | 23.6 | 19.9 | |||

| ACMG-AMP recommendation | class 5 | class 5 | class 5 | |||

| Human Splicing Finder | not applicable | not applicable | affecting splicing | |||

| Exome Variant Server | absent | absent | absent | |||

| 1000 Genomes Project | absent | absent | absent | |||

| ExAC | absent | absent | absent | |||

| Human Genetic Variation | absent | absent | absent | |||

| dbSNP 138 | absent | absent | absent | |||

| in-house control | absent | absent | absent | |||

F: female; M: male; NE: not examined; MIBG scinti: 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy; DAT SPECT: dopamine transporter single photon emission computed tomography using 123I-ioflupane; SIFT: Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant; CADD: Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion; ACMG-AMP: the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology; ExAC: The Exome Aggregation Consortium.

Case descriptions

Family 1

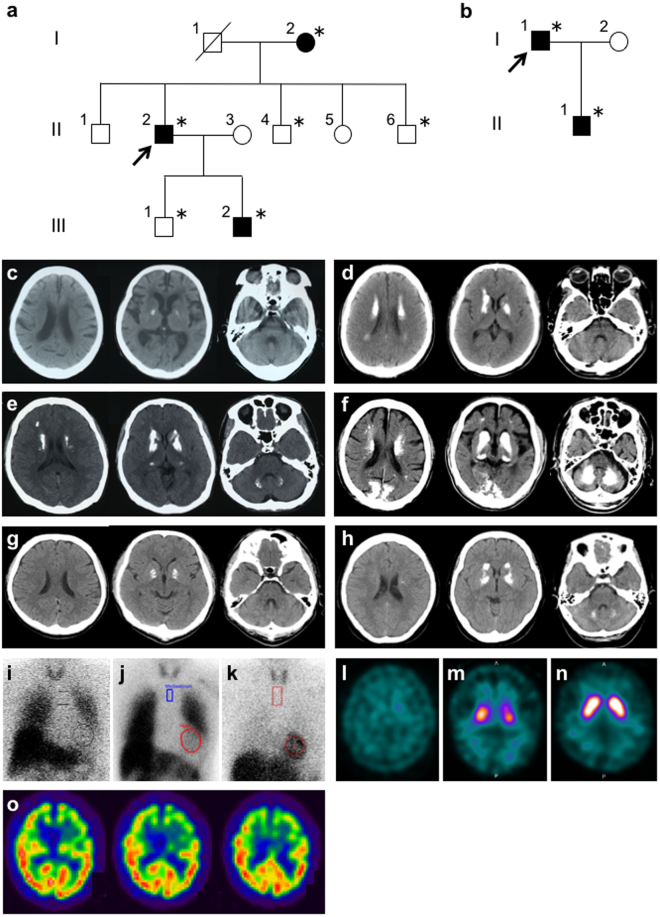

The proband of Family 1 (II:2; Fig. 1a) was a 62-year-old Japanese man who presented with a 2-year history of slowness and gait disturbance. Neurological examination revealed resting tremor in the left hand, bradykinesia, and small shuffling gait. There were no pathological reflexes or signs of ataxia. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was 30/30. His parkinsonism responded to treatment with L-dopa/carbidopa. Brain computed tomography (CT) showed calcification in the lenticular nuclei, caudate nuclei, and deep white matter (Fig. 1d). Decreased cardiac uptake in 123I- MIBG scintigraphy was observed (the early image heart/mediastinum ratio was 1.43) (Fig. 1i). Dopamine transporter SPECT using 123I-ioflupane demonstrated a marked decrease of striatal tracer uptake with a right-side predominance (Fig. 1l). The 89-year-old mother of the proband (I:2; Fig. 1a) was in a bedridden state with resting tremor in her left hand. Her brain CT revealed a mild calcification in the bilateral lenticular nuclei (Fig. 1c). Considering her age, calcified lesions could be considered as physiological. She was not treated with anti-parkinsonian drugs. The 27-year-old son of the proband (III:2; Fig. 1a) was clinically asymptomatic. His brain CT showed calcification in the lenticular nuclei, caudate nuclei, thalami, subcortical white matter, and dentate nuclei (Fig. 1e). No calcified lesions were detected in the proband’s brothers (II:4 and II:6; Fig. 1a) and the proband’s son (III:1; Fig. 1a) on brain CT images. Calcified lesions on brain CT were observed across three generations in this family. In addition, anticipation of CT imaging was noticed, although the affected proband’s son (III:2; Fig. 1a) had not exhibited any neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of Family 1 (a) and Family 2 (b). Squares: males; circles: females. The arrowheads denote the probands. The filled symbols represent the subjects with calcinosis. Asterisks represent individuals who are included in this study. Brain computed tomography (CT) images demonstrating brain calcinosis in patients of this study with genetically confirmed primary familial brain calcification (c–h). (c) the proband’s mother of Family 1; (d) the proband of Family 1; (e) the proband’s affected son; (f) the proband of Family 2; (g) the proband’s son of Family 2; (h) sporadic case 1. 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy in the proband of Family 1 (i), the proband of Family 2 (j), and the proband’s son of Family 2 (k). Dopamine transporter single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) using 123I-ioflupane (l–n) in the proband of Family 1 (l) and the proband of Family 2 (m) showing a decrease of striatal tracer uptake. In the proband’s son of Family 2, tracer uptake is normal (n). Brain 99mTc-ethyl cysteinate dimer SPECT in the proband of Family 2 (o) showing a hypoperfusion in the frontotemporal lobes with a left-side predominance.

Family 2

The proband of Family 2 (I:1; Fig. 1b) was a 79-year-old Japanese man presenting with a 5-year history of dementia. His MMSE score was 13/30. His psychiatric symptoms were decreased motivation, irritability, shouting, disinhibition, and impulsive violent behavior. Impaired attention was evident on the digit span task (four digits forward and three digits backward). The number of words recalled on 10-word recall subtest of Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale was 1/10. His Frontal Assessment Battery score was 3 of 18 with deficits in all of the items except environmental autonomy. Neither visual nor auditory hallucinations were evident. Fluctuations in cognitive function were not apparent. The patient also exhibited mild parkinsonism with a right-side predominance. His brain CT revealed marked calcified lesions in the lenticular nuclei, caudate nuclei, thalami, dentate nuclei, subcortical white matter, and occipital cortical-subcortical regions (Fig. 1f). Decreased cardiac uptake in 123I-MIBG scintigraphy was demonstrated (the early image heart/mediastinum ratio was 1.62) (Fig. 1j). A left-side predominant decrease of tracer uptake in the striatum was observed in dopamine transporter SPECT (Fig. 1m). Brain 99mTc-ethyl cysteinate dimer (99mTc-ECD) SPECT revealed left-side predominant frontotemporal hypoperfusion (Fig. 1o). The 52-year-old son of the proband was diagnosed with depression at the age of 50 years. He also experienced headache. Neurological examination revealed no signs of ataxia or parkinsonism. His MMSE score was 30/30. His brain CT showed calcification in the lenticular nuclei (Fig. 1g). Cardiac uptake of 123I-MIBG was normal (the early image heart/mediastinum ratio was 3.24) (Fig. 1k). Dopamine transporter SPECT demonstrated a normal uptake in the striatum (Fig. 1n).

Sporadic case 1

A 50-year-old woman referred besecause of ptosis and diplopia was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, based on a positive response to intravenous edrophonium chloride and the presence of antibodies to acetylcholine receptor. She was successfully treated with ambenonium chloride and tacrolimus. Brain CT performed to assess her ocular manifestations incidentally disclosed calcinosis in the lenticular nuclei, caudate nuclei, and dentate nuclei (Fig. 1h). She was also diagnosed as being in a depressive state. There were no other neurological symptoms other than those related to myasthenia gravis. She had no family history of any neuropsychiatric disorders.

Genetics

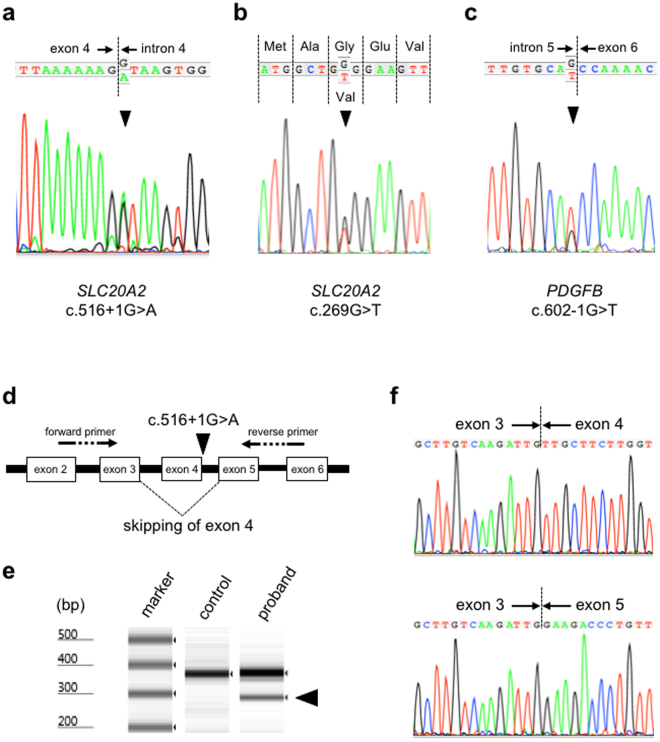

PFBC is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous condition. Therefore, amplicon-based next-generation sequencing of the three familial probands and the eight sporadic patients was performed to determine the causative mutations in this study. We performed genetic analysis according to the mutation detection strategy (Supplementary Table 2, Materials and Methods). The mean read depth and the total number of detected variants by the two pipelines constructed with Bowtie2-GATK (the Genome Analysis Toolkit) and BWA (Burrows Wheeler Alignment)-Platypus at the whole exome level are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Coverage for the four genes are summarized in Supplementary Table 4. The number of detected variants called by the two pipelines and the disease-causing variants obtained after filtering process are also shown in Supplementary Table 4. According to the filtering process (Supplementary Table 2), we identified three novel mutations in genes known to be responsible for PFBC: two of them were detected in SLC20A2. A G-to-A transition at the +1 splice donor position in intron 4 of SLC20A2 (c.516+1G > A) was revealed in the proband of Family 1 in a heterozygous state (Fig. 2a). Human Splicing Finder (HSF) predicted this mutation to affect splicing through alteration of the wild-type donor site. Sanger sequencing confirmed that only subjects with brain calcifications on CT carried the mutation in this family. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of the patient showed an additional fast-migrating band in addition to a PCR product of the expected size (Fig. 2 d, e). Sanger sequencing demonstrated that the mutation resulted in the skipping of exon 4 of SLC20A2 (r.431_516del, p.Val144Glyfs*85) (Fig. 2f). In the proband of Family 2, WES detected a heterozygous G-to-T transversion in the coding region of exon 2 (c.269G > T), resulting in a glycine-to-valine substitution at position 90, p.(Gly90Val) in SLC20A2 (Fig. 2b). Sanger sequencing identified the c.269G > T mutation in both the proband and his affected son. This mutation was predicted as probably damaging and deleterious by Polyphen-2 and Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT), respectively. In sporadic case 1, we found a heterozygous G-to-T transversion in PDGFB located at the base pair immediately flanking the 5′ end of exon 6 (c.602-1G > T, p.?) (Fig. 2c). This variant was predicted to lead to the alteration of the wild-type acceptor site by HSF. The three detected variants were considered to be deleterious by Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) (all phred-like scores were higher than 15, Table 1). The above two splicing variants were classified as pathogenic (class 5) and the missense SLC20A2 variant was considered as likely pathogenic (class 4) according to the recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG-AMP) (Table 1). The above mutations were not detected in publicly available databases: NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP6500), dbSNP 138, 1000 Genomes Project, The Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), Human Genetic Variation Database (HGVD), and in-house exome sequencing data of 128 control subjects. Furthermore, these mutations were not listed in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) or ClinVar. In additon, we assessed copy number variations (CNVs) using WES data, but we could not detect CNVs in the candidate four genes responsible for PFBC.

Figure 2.

Electropherograms of Sanger sequences of the proband of Family 1 (a), the proband of Family 2 (b), and sporadic case 1 (c). Arrowhead in A indicates the c.516+1G > A mutation in SLC20A2. Arrowhead in B shows the c.269G > T mutation in SLC20A2. Arrowhead in C represents the c.602-1G > T mutation in PDGFB. (d) Schematic representation of the c.516+1G > A mutation in SLC20A2 and the primers used in reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis to demonstrate the skipping of exon 4. (e) RT-PCR analysis showing another transcript in the proband of Family 1 carrying the c.516+1G > A mutation in SLC20A2. In addition to a PCR product of the expected size (355 bp), a fast-migrating band is observed (arrowhead). (f) Sanger sequencing of the RT-PCR products demonstrating that the c.516+1G > A mutation in SLC20A2 leads to the skipping of exon 4.

Discussion

SLC20A2 mutations are a major cause of PFBC and account for about one-half of all familial cases. To date, more than 40 disease-causing mutations have been identified2,24. SLC20A2 [solute carrier family 20 (phosphate transporter) member 2] encodes the type III sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate (Pi) transporter 2, PiT-2. Mutagenesis analysis in Xenopus laevis oocytes showed that disease-causing mutants decreased Pi uptake activity without an obvious effect on the wild-type PiT-2 function, indicating that the underlying mechanism is due to haploinsufficiency rather than a dominant-negative effect6. This idea is supported by a PFBC case with a heterozygous deletion of the entire SLC20A2 gene25. In addition, partial, mono- or di-exonic SLC20A2 deletions have also been reported to cause this condition26. Jensen et al. reported that Slc20a2 knockout mice demonstrate brain calcifications, suggesting that the functional deficit of PiT-2 is implicated in the pathophysiology of SLC20A2-related PFBC27. In our study, WES of the proband of Family 1 successfully detected a novel splice donor site mutation, c.516+1G > A. Sanger sequencing of the family members revealed that the mutation completely co-segregated with the calcification phenotype within the pedigree. RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the mutation led to a frameshift and a premature stop codon. The truncated protein is considered to be functionally null. In addition, we found a novel missense mutation, p.(Gly90Val), in Family 2. Glycine90 is located in the third transmembrane domain of PiT-2 and is present within the ProDom domain, characteristic for all PiT family members. Although the exact effect of this mutation on PiT-2 function is unclear, the residue is evolutionarily conserved from Homo sapiens to Danio rerio, supporting its functional importance.

Mutations in PDGFB, the gene encoding platelet derived growth factor β (PDGF-B), the main ligand for platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGF-Rβ), have been reported to cause PFBC8. PDGFB is thought to be the second most common causative gene after SLC20A2 for this condition28,29. To date, 13 mutations in PDGFB have been found8,10,29–33, including three nonsense mutations (p.Gln145*, p.Gln147*, and p.Arg149*) and five missense mutations (p.Leu9Arg, p.Ala95Thr, p.Leu110Val, p.Leu119Pro, and p.Pro122Leu). A splice-site mutation, c.64-3C > G, is predicted to result in a premature stop codon. The c.3G > A and c.3G > C mutations replace the start methionine and c.726G > C (p.*242Tyrext*89) substitutes the stop codon with a tyrosine, resulting in an extended PDGF-B protein. PFBC-associated PDGF-B mutations are thought to cause complete loss of function through either reduced protein levels of PDGF-B or abolished PDGF-Rβ phosphorylation34. In addition, a partial intragenic large deletion within PDGFB, c.161-238_602-676del441 (p.Glu54Aladel147) has been reported in a patient with brain calcification and leukoencephalopathy, indicating a loss-of-function mechanism for PDGFB-related PFBC30. This hypothesis is supported by the detection of brain calcifications in PDGF-B retention motif knockout mice8. Furthermore, mutations in PDGFRB, which encodes for the transmembrane receptor PDGF-Rβ are also responsible for PFBC6. Five missense mutations (p.Leu658Pro, p.Arg695Cys, p.Asp737Asn, p.Arg987Trp, and p.Glu1071Val) and the c.3G > A variant have been reported3,7,35,36. Sanchez-Contreras et al. reported that the PFBC-causing p.Arg695Cys and p.Leu658Pro mutations cause impairment of PDGF-Rβ autophosphorylation in a cell culture with PDGF-BB, a recombinant human PDGF-B homodimer. The p.Arg987Trp mutation resulted in a decreased level of PDGF-Rβ protein because of accelerated degradation by the proteasome35. Taken together, an impairment of the PDGF-B/PDGF-Rβ pathway could cause brain calcification. Interestingly, mutations in PDGFRB also cause autosomal-dominant infantile myofibromatosis, Penttinen syndrome, and a novel overgrowth syndrome characterized by somatic overgrowth, distinctive facial features, hyper-elastic and fragile skin, white matter lesions, and neurologic deterioration37–40. In contrast to the PFBC-related mutations, the Penttinen syndrome-causing p.Val665Ala PDGF-Rβ variant exhibits robust ligand-independent autophosphorylation and constitutive PDGF-Rβ signaling through STAT3 and PLCγ38. The p.Arg561Cys mutation in familial infantile myofibromatosis is predicted in silico to decrease autoinhibition of PDGF-Rβ and lead to high PDGF-Rβ signaling activity, suggesting that a gain-of-function mechanism contributes to the pathogenesis of this condition39. In this study, we identified a novel splice acceptor site mutation in PDGFB. Although we have not examined the exact effect on splicing at the transcript level, the c.602-1G > T mutation is predicted in silico to affect splicing, supporting the idea that loss-of-function mutations in PDGFB cause PFBC.

In the present study, we identified three novel mutations in SLC20A2 and PDGFB. On the other hand, we could not detect the causative mutation in the known PFBC-causing genes in the remaining cases. Mutations in SLC20A2, PDGFRB, PDGFB, and XPR1 have been reported to be responsible for PFBC6–9; however, these four disease-causing genes do not account for all cases of PFBC, indicating additional genetic heterogeneity5. One mutation was detected in a seemingly sporadic case in this study. Some patients with a sporadic presentation have been diagnosed with definite PFBC based on genetic analysis. Strictly speaking, the absence of a family history of PFBC-associated signs in relatives is not sufficient to exclude inheritance because of its incomplete clinical penetrance, whereas true sporadic cases due to de novo mutations have been reported10,11. Therefore, we should be careful to ensure that patients with PFBC are really sporadic without genetic analysis and/or brain imaging of their first-degree relatives. PFBC patients exhibit a variety of clinical presentations. Furthermore, clinical diversity is recognized within and between families with PFBC3. In Family 2, the proband had dementia and parkinsonism, whereas his son was diagnosed with depression but not with dementia or parkinsonism at the time of diagnosis. On the other hand, patients with the p.Ser637Arg SLC20A2 mutation exhibit similar neurological symptoms17. In the present study, interestingly, the proband of Family 1 and his mother also had a similar clinical presentation of asymmetric parkinsonism including bradykinesia and resting tremor.

Parkinsonism is the most common symptom after dystonia in PFBC-related movement disorders4. As observed in the present cases, pre-synaptic nigrostriatal dopaminergic dysfunction was reported in patients with PFBC13–16. Nevertheless, although the exact reason is unclear, the response to L-dopa therapy is different among patients. Saito et al. showed that the post-synaptic dopaminergic impairment was also observed in a case of PFBC14. The degree of post-synaptic dopaminergic disability in the striatum might explain variations in the effectiveness of anti-parkinsonian medications. The relationship between PFBC and Lewy body pathology remains controversial. Manyam et al. reported a familial case of PFBC, in which the proband presenting with parkinsonism showed Lewy bodies indicative of Parkinson’s disease in the substantia nigra, while another patient from the same family with clinical evidence of parkinsonism did not demonstrate Lewy body pathology18. As previously mentioned, therefore, it is possible that the co-occurrence of PFBC and Lewy body-related conditions is incidental17,18. However, neuropathological examinations revealed neuronal loss and Lewy bodies in SLC20A2-related PFBC patients presenting with parkinsonism17,19. Further genetic and neuropathological examinations of PFBC are required to answer the question of whether Lewy bodies are age-related incidental findings or whether they have certain associations with the pathomechanisms underlying PFBC. Interestingly, although pathological examinations were not performed in the present study, in addition to the decrease of tracer uptake in dopamine transporter SPECT, decreased cardiac uptake in 123I-MIBG scintigraphy was also demonstrated in our patients with parkinsonism, consistent with Lewy body-related conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies23. In fact, in the proband of Family 1, his parkinsonism was clinically indistinguishable from idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. A reduction in cardiac MIBG uptake was also revealed in the proband of Family 2; however, the clinical picture, including brain 99mTc-ECD SPECT findings, was similar to that of frontotemporal lobar degeneration rather than dementia with Lewy bodies, except that parkinsonism was also present.

In conclusion, we identified three novel mutations in SLC20A2 and PDGFB responsible for PFBC in two familial cases and one sporadic case using WES. Genetic analysis should be considered, even in apparently sporadic cases, for the precise diagnosis of PFBC because clinical penetrance is incomplete. To elucidate the underlying mechanism of PFBC-related parkinsonism, radiological assessments including 123I-MIBG cardiac scintigraphy and dopamine transporter SPECT in a larger sample of patients are required.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Seven patients and five relatives from three PFBC families with an autosomal dominant inheritance and eight sporadic cases were enrolled in this study. The clinical criteria for PFBC are described elsewhere41. The serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone were all within normal limits in the patients. Subjects with brain calcifications on CT were classified as affected regardless of their clinical status. Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood of the patients and relatives after obtaining their written informed consent. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Mutation detection strategy

To determine the causative mutations, we performed genetic analysis according to the mutation detection strategy in this study (Supplementary Table 2).

Whole exome sequencing

WES of the three familial probands and of eight sporadic patients was performed using amplicon-based, next-generation sequencing as previously described42. Briefly, libraries were constructed using an Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit v2.0 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantification of the libraries was performed on a 2200 TapeStation Instrument using High Sensitivity D1000 Reagents and High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Amplified libraries were submitted to emulsion PCR using an Ion OneTouch™ 2 Instrument with an Ion PI™ Template OT2 200 Kit v3. Ion sphere particles were enriched using Ion OneTouch ES and were loaded on an Ion PI Chip v2. Sequencing was performed by Ion Proton™ with an Ion PI Sequencing 200 Kit v3. Read sequence files were run through two independent pipelines constructed with Bowtie2 (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml)-GATK (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/index.php) and BWA (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/bwa.shtml)-Platypus (http://www.well.ox.ac.uk/platypus) to obtain variant call format files. Then, concordant genetic variants detected by the two pipelines were annotated using ANNOVAR (http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org). We focused on genes previously reported to be responsible for PFBC (SLC20A2, PDGFB, PDGFRB, and XPR1) and picked up the variants in the coding regions and exon-intron boundaries of these four genes.

Variant analysis

To avoid missing variants, BAM files were loaded into Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv) for visual inspection for the candidate four genes. After excluding synonymous mutations, the variants with a minor allele frequency of less than 0.1% in the following databases were extracted: ESP6500 (http://evs.gs.washington.edu), dbSNP 138 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org), ExAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and HGVD (http://www.genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/SnpDB/). The detected variants were queried in the two mutation databases: HGMD (http://www.hgmd.org) and ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). The pathological potential of the identified variants was evaluated using in silico prediction methods: PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) and SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) for the missense variant, HSF (http://www.umd.be/HSF3/HSF.html) for the splice-site variants, and CADD (http://cadd.gs.washington.edu/info) for both splice site and nonsynonymous variants. We followed the ACMG-AMP recommendation for the clinical interpretation of the detected variants43. To detect CNVs using WES data, we ran a hidden Markov model algorithm as previously described42. The nomenclature of the detected variants refers to transcripts NM_006749.4 for SLC20A2 and NM_002608.3 for PDGFB.

Sanger sequencing

Regarding the target regions covered by five or fewer reads, Sanger sequencing was performed to examine all the coding regions and exon-intron boundaries of the four genes. In addition, the mutations identified by WES were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Primers sequences are described elsewhere6–9. PCR products were sequenced using a BigDyeV3.1 terminator Kit on an ABI 3100 automated sequencer (Life Technologies).

RT-PCR

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). Total RNA was purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Maryland, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was treated with DNase (RNase-Free DNase Set; Qiagen) to avoid contamination of genomic DNA. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using Ready-to-Go You Prime First-Strand Beads (GE Healthcare) with random hexamers (Random primer; TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). To examine the effect of the SLC20A2 mutation on splicing, RT-PCR was carried out with a forward primer spanning exons 2 and 3 (5′-ttagtgccatggttggttcc-3′) and a reverse primer straddling exons 5 and 6 (5′-gagaacaaggccgagcact-3′). The size of PCR products was assessed using a 2200 TapeStation Instrument. The amplified PCR fragments were subcloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and were sequenced with a T7 promoter primer on an ABI 3100 automated sequencer.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their family members who participated in this study. We are grateful to Ms. T. Seino for her technical assistance. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant No. JP24790872.

Author Contributions

S. Koyama conceived and coordinated the project, collected and analyzed clinical data, designed and performed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. H.S. performed the experiments. R.K., S. Kawakatsu, M.K., M.W., and T. Kawanami collected and analyzed clinical data. T. Kato supervised the project and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11595-1

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Manyam BV. What is and what is not 'Fahr's disease'. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2005;11:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westenberger A, Klein C. The genetics of primary familial brain calcifications. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2014;14:490. doi: 10.1007/s11910-014-0490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolas G, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of probable and genetically-confirmed idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Brain. 2014;136:3395–3407. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tadic V, et al. Primary familial brain calcification with known gene mutations: a systematic review and challenges of phenotypic characterization. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:460–467. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliveira JR, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification (Fahr disease) Neurology. 2004;63:2165–2167. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000145601.88274.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C, et al. Mutations in SLC20A2 link familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification with phosphate homeostasis. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:254–256. doi: 10.1038/ng.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolas G, et al. Mutation of the PDGFRB gene as a cause of idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Neurology. 2013;80:181–187. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827ccf34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keller A, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding PDGF-B cause brain calcifications in humans and mice. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1077–1082. doi: 10.1038/ng.2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legati A, et al. Mutations in XPR1 cause primary familial brain calcification associated with altered phosphate export. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:579–581. doi: 10.1038/ng.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolas G, et al. A de novo nonsense PDGFB mutation causing idiopathic basal ganglia calcification with laryngeal dystonia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;22:1236–1238. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira JB, et al. First report of a de novo mutation at SLC20A2 in a patient with brain calcification. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2014;54:748–751. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemos RR, et al. Update and Mutational Analysis of SLC20A2: A Major Cause of Primary Familial Brain Calcification. Hum. Mutat. 2015;36:489–495. doi: 10.1002/humu.22778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paschali A, et al. Dopamine transporter SPECT/CT and perfusion brain SPECT imaging in idiopathic basal ganglia calcinosis. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2009;34:421–423. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181a7d195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito T, et al. Neuroradiologic evidence of pre-synaptic and post-synaptic nigrostriatal dopaminergic dysfunction in idiopathic Basal Ganglia calcification: a case report. J. Neuroimaging. 2010;20:189–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2008.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paghera B, Caobelli F, Giubbini R. 123I-ioflupane SPECT in Fahr disease. J. Neuroimaging. 2013;23:157–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2011.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anheim M, et al. XPR1 mutations are a rare cause of primary familial brain calcification. J. Neurol. 2016;263:1559–1564. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada M, et al. Evaluation of SLC20A2 mutations that cause idiopathic basal ganglia calcification in Japan. Neurology. 2014;82:705–712. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manyam BV, Walters AS, Keller IA, Ghobrial M. Parkinsonism associated with autosomal dominant bilateral striopallidodentate calcinosis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2001;7:289–295. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(00)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura T, et al. Familial idiopathic basal ganglia calcification: Histopathologic features of an autopsied patient with an SLC20A2 mutation. Neuropathology. 2015;36:365–371. doi: 10.1111/neup.12280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Courbon F, et al. Cardiac MIBG Scintigraphy Is a Sensitive Tool for Detecting Cardiac Sympathetic Denervation in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2003;18:890–897. doi: 10.1002/mds.10461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postuma RB, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2015;30:1591–1601. doi: 10.1002/mds.26424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKeith IG, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89:1–13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King AE, Mintz J, Royall DR. Meta-analysis of 123I-MIBG cardiac scintigraphy for the diagnosis of Lewy body-related disorders. Mov. Disord. 2011;26:1218–1224. doi: 10.1002/mds.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taglia I, Bonifati V, Mignarri A, Dotti MT, Federico A. Primary familial brain calcification: update on molecular genetics. Neurol. Sci. 2015;36:787–794. doi: 10.1007/s10072-015-2110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker M, et al. SLC20A2 and THAP1 deletion in familial basal ganglia calcification with dystonia. Neurogenetics. 2014;15:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s10048-013-0378-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.David S, et al. Identification of partial SLC20A2 deletions in primary brain calcification using whole-exome sequencing. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;24:1630–1634. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen N, et al. Loss of function of Slc20a2 associated with familial idiopathic Basal Ganglia calcification in humans causes brain calcifications in mice. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2013;51:994–999. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0085-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicolas G, et al. Overall mutational spectrum of SLC20A2, PDGFB and PDGFRB in idiopathic basal ganglia calcification. Neurogenetics. 2014;15:215–216. doi: 10.1007/s10048-014-0404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicolas G, et al. Brain calcification process and phenotypes according to age and sex: Lessons from SLC20A2, PDGFB, and PDGFRB mutation carriers. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2015;168:586–594. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicolas G, et al. PDGFB partial deletion: a new, rare mechanism causing brain calcification with leukoencephalopathy. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2014;53:171–175. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0265-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashi T, Legati A, Nishikawa T, Coppola G. First Japanese family with primary familial brain calcification due to a mutation in the PDGFB gene: an exome analysis study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015;69:77–83. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keogh MJ, et al. Clinical heterogeneity of primary familial brain calcification due to a novel mutation in PDGFB. Neurology. 2015;84:1818–1820. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biancheri R, et al. White matter involvement in a family with a novel PDGFB mutation. Neurol. Genet. 2016;2:e77. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanlandewijck M, et al. Functional Characterization of Germline Mutations in PDGFB and PDGFRB in Primary Familial Brain Calcification. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0143407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez-Contreras M, et al. Genetic screening and functional characterization of PDGFRB mutations associated with basal ganglia calcification of unknown etiology. Hum. Mutat. 2014;35:964–71. doi: 10.1002/humu.22582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang, C. et al. Novel mutations of PDGFRB cause primary familial brain calcification in Chinese families. J. Hum. Genet. Epub ahead of print (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Martignetti JA, et al. Mutations in PDGFRB cause autosomal-dominant infantile myofibromatosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;92:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston JJ, et al. A Point Mutation in PDGFRB Causes Autosomal-Dominant Penttinen Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;97:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheung YH, et al. A recurrent PDGFRB mutation causes familial infantile myofibromatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:996–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takenouchi T, et al. Novel overgrowth syndrome phenotype due to recurrent de novo PDGFRB mutation. J. Pediatr. 2015;166:483–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonazza S, La Morgia C, Martinelli P, Capellari S. Strio-pallido-dentate calcinosis: a diagnostic approach in adult patients. Neurol. Sci. 2011;32:537–545. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koyama S, et al. Whole-exome sequencing and digital PCR identified a novel compound heterozygous mutation in the NPHP1 gene in a case of Joubert syndrome and related disorders. BMC Med. Genet. 2017;18:37. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0399-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article.