Abstract

The first aim of this study was to investigate the concurrent and longitudinal relationships between adolescents' use of social network sites (SNSs) and their social self-esteem. The second aim was to investigate whether the valence of the feedback that adolescents receive on SNSs can explain these relationships. We conducted a three-wave panel study among 852 pre- and early adolescents (10–15 years old). In line with earlier research, we found significant concurrent correlations between adolescents' SNS use and their social self-esteem in all three data waves. The longitudinal results only partly confirmed these concurrent findings: Adolescents' initial SNS use did not significantly influence their social self-esteem in subsequent years. In contrast, their initial social self-esteem consistently influenced their SNS use in subsequent years. The valence of online feedback from close friends and acquaintances explained the concurrent relationship between SNS use and social self-esteem, but not the longitudinal relationship. Results are discussed in terms of their methodological and theoretical implications.

Keywords: Online communication, Social network sites, Social media, Social self-esteem, Self-esteem, Social comparison, SNS, Feedback, Media effects

Highlights

-

•

Social self-esteem (SSE) longitudinally predicts higher SNS use.

-

•

SNS use marginally predicts over-time improvements in SSE.

-

•

Feedback from friends and acquaintances explains the concurrent SNS-SSE relation.

-

•

Feedback from friends leads to over-time improvements in SSE.

-

•

Feedback from acquaintances does not result in over-time changes in SSE.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a transitional phase characterized by significant psychosocial changes. An important developmental task that adolescents need to accomplish is to develop a coherent sense of self (i.e., a view of who they are and who they want to become) and a relatively stable feeling of overall self-worth, that is, self-esteem. Self-esteem is one of the main predictors of psychological well-being (Baumeister et al., 2003, Harter, 2012a), and acquiring an adequate level of self-esteem is crucial to adolescent development. Adolescents' self-esteem is widely acknowledged to be a multidimensional and hierarchical concept that consists of several different components, including scholastic, social, athletic, and physical self-esteem (Harter, 2012a, Marsh and Craven, 2006). Together, these self-esteem components are significant predictors of global self-esteem (Harter, Whitesell, & Junkin, 1998), and individually, they more strongly predict related developmental outcomes than other self-esteem components do. For example, scholastic self-esteem is a significant predictor of academic outcomes, whereas social or physical self-esteem are weaker predictors of such outcomes (Marsh & Craven, 2006).

In this study, we aim to investigate the relationships between adolescents' use of social network sites (SNSs) and their social self-esteem, defined as the extent to which they feel accepted and liked by their friends and peers and feel successful in forming and maintaining friendships. Social self-esteem is largely shaped through interactions with close friends and peers, and as a result, such interactions play a central role in the development of adolescents' social and global self-esteem (Harter, 2012a). Today, a significant part of adolescents' interactions with close friends and peers occur via social network sites (SNSs), such as Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram (Valkenburg & Piotrowski, 2017). Given that social self-esteem is one of the strongest predictors of global self-esteem (Harter, 2012b), we believe that if there is one component of adolescents' global self-esteem that might be related to their peer interactions on SNSs, it is their social self-esteem.

Several earlier studies have investigated the relationship between adolescents' social media use and self-esteem. Some studies have focused on the relationship between social media use and global self-esteem (Apaolaza et al., 2013, Blomfield Neira and Barber, 2014, Gross, 2009, Jackson et al., 2010), whereas others have investigated social self-esteem (Blomfield Neira and Barber, 2014, Jackson et al., 2010, Valkenburg et al., 2006). These studies have focused on different types of social media use, including the time spent on SNSs (Apaolaza et al., 2013, Blomfield Neira and Barber, 2014, Valkenburg et al., 2006), time spent with instant messaging (Gross, 2009, Jackson et al., 2010), and homepage or weblog creation (Schmitt, Dayanim, & Matthias, 2008).

Of the seven studies among adolescents that investigated the relationship between social media use and self-esteem, five reported a positive relationship with global self-esteem (Apaolaza et al., 2013, Gross, 2009, Schmitt et al., 2008) or social self-esteem (Blomfield Neira and Barber, 2014, Valkenburg et al., 2006). In addition, one study found a non-significant (positive) relationship with both global and social self-esteem (Jackson et al., 2010), and another found a negative relationship with global self-esteem (O'Dea & Campbell, 2011). However, when social media use becomes intense or addictive, these preponderating positive results are reversed into negative relationships with both global and social self-esteem (Blomfield Neira and Barber, 2014, Fioravanti et al., 2012, van den Eijnden et al., 2016, van der Aa et al., 2009).

Although the weight of evidence thus points to a positive relationship between adolescents' social media use and their self-esteem, the existing literature has two important gaps. First, it particularly lacks studies based on longitudinal data and, therefore, the direction of the relationship between social media use and social self-esteem remains unclear (Liu & Baumeister, 2016). Although most previous studies have conceptualized global and social self-esteem as the outcome variable, it is just as likely that adolescents' level of social self-esteem is the cause and social media use the result. Second, many studies have tested whether there is a relationship between SNS use and social self-esteem, but not why (but see, e.g., de Vries and Kühne, 2015, Thomaes et al., 2010, Valkenburg et al., 2006). Therefore, knowledge about possible underlying mechanisms that may explain this relationship is largely lacking. The aim of the current study is to address these two gaps in the literature. First, we will investigate the longitudinal relationship between adolescents' SNS use and their social self-esteem, and compare this relationship with the concurrent findings that have been reported in previous research. Second, we will investigate an important underlying mechanism that may explain the concurrent and longitudinal relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem, namely the extent to which adolescents receive positive feedback on SNSs.

The focus of our study is on pre- and early adolescents (age 10–15). Developmental research agrees that there is no stage of life-span development in which feedback on the self is so likely to affect self-esteem as during this period. Especially early adolescence is characterized by an increased focus on the self. Early adolescents often tend to overestimate the extent to which others are watching and evaluating them, and can be highly preoccupied with how they appear in the eyes of others (Elkind & Bowen, 1979). On SNSs, interpersonal feedback on the self, whether positive or negative, is often more public and visible than in comparable face-to-face settings, which may make pre- and early adolescents more susceptible to such feedback than comparable feedback in face-to-face settings.

1.1. SNS use and (social) self-esteem among adolescents and adults

Research into the relationship between SNS use and self-esteem has been burgeoning since the introduction of Facebook in 2007. In a recent meta-analysis, Liu and Baumeister (2016) retraced 33 independent studies, conducted between 2008 and 2016, on the relationship between SNS use and global self-esteem. Their meta-analysis revealed mixed results for different indicators of SNS use: Time spent on SNSs resulted in a negative correlation (r = −0.09, p < .01) with global self-esteem, whereas the number of friends of SNS users led to a positive correlation (r = 0.07, p < .001). The meta-analysis further revealed three non-significant relationships between global self-esteem and the frequency of interactions on SNSs (r = .11), the frequency of status updates (r = −0.02), and the number of photos uploaded (r = −0.01).

Although valuable, the meta-analysis of Liu and Baumeister (2016) does not allow of decisive conclusions about the relationship between SNS use and self-esteem among adolescents, firstly because most of the studies among adolescents were not included in their meta-analysis (i.e., Apaolaza et al., 2013, Blomfield Neira and Barber, 2014, Gross, 2009, Jackson et al., 2010, O'Dea and Campbell, 2011, Schmitt et al., 2008, Valkenburg et al., 2006). And secondly, because there is initial evidence that the positive relationship between social media use and self-esteem may hold for adolescents but not for adults (Gross, 2009). This discrepancy in results may be due to differences in SNS use by adolescents and adults. Most adolescents use social media to communicate with their existing friends (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011), and they typically receive positive (rather than negative) online feedback from these friends (Koutamanis et al., 2015, Valkenburg et al., 2006). This preponderating positive online feedback may help them develop a favorable view of their selves, just like offline interpersonal feedback from these same friends may do (Valkenburg et al., 2006). Finally, given that adolescents are more susceptible than adults to positive (and negative) feedback, the effect of peer interactions on SNSs on adolescents' self-esteem may be larger than similar effects on adults' self-esteem.

1.2. The causal direction of the relationship between SNS use and social self-esteem

Another reason why the results of Liu and Baumeister's (2016) meta-analysis do not allow of decisive conclusions is that virtually all of their included studies were correlational. To date, most of the studies among adolescents have been based on the hypothesis that SNS use influences social or global self-esteem (e.g., Apaolaza et al., 2013, Valkenburg et al., 2006), but, in fact, the opposite hypothesis—that their self-esteem affects their SNS use— is equally plausible. People are typically more attracted to media that are consistent with their personality traits (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). In the case of SNS use, this would imply that adolescents with higher social self-esteem are more likely than their peers with lower self-esteem to interact with friends online (Kraut et al., 2002, Valkenburg and Peter, 2013). To investigate the direction of the SNS use-self-esteem relationship, we will investigate two opposite hypotheses: Adolescents' use of SNSs will stimulate their social self-esteem (Hypothesis 1a), and adolescents' social self-esteem will lead to increases in their SNS use (Hypothesis 1b).

1.3. Online feedback as an underlying mechanism

The second aim of our study is to investigate whether positive feedback on SNSs could explain the preponderantly positive relationships between adolescents' social media use and social self-esteem reported in previous studies. Three earlier studies, two correlational (Greitemeyer et al., 2014, Valkenburg et al., 2006) and one experimental (Thomaes et al., 2010), have investigated the relationship between feedback on SNSs and social or global self-esteem. These studies found that positive feedback from friends improved social or global self-esteem (Greitemeyer et al., 2014, Thomaes et al., 2010, Valkenburg et al., 2006), whereas negative feedback from and neglect by friends decreased global and social self-esteem (Thomaes et al., 2010, Valkenburg et al., 2006).

One important explanation of why positive feedback may account for the positive relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem may lie in the “positivity bias” that characterizes SNS interactions (Reinecke & Trepte, 2014). Most social media are designed to stimulate positive interactions among users, for example via “likes” and “favorites.” Generally, humans have a tendency towards sharing positive (rather than negative) news about themselves, but this tendency seems to hold particularly for SNS users (Bazarova, Choi, Sosik, Cosley, & Whitlock, 2015). In addition, like in any dynamic communication between senders and receivers, these positive disclosures beget positive or supportive feedback from receivers (Burke & Develin, 2016). Indeed, most SNS users predominantly receive positive feedback on their postings or status updates (Greitemeyer et al., 2014, Koutamanis et al., 2015), which in turn may stimulate their social self-esteem (Valkenburg et al., 2006).

Another explanation for the positive relationship between SNS use and social self-esteem may lie in several affordances of SNS, most notably their scalability, asynchonicity, and cue-manageability (boyd, 2011, Valkenburg, 2017). Scalability offers SNS users the ability to articulate personal messages to any size or nature of audiences, which enhances the likelihood that they receive positive feedback from these expanded audiences (Valkenburg, 2017). The asynchronicity affordance offers SNS users the possibility to communicate when it suits them, synchronously (in real time) or asynchronously (delayed). Asynchronous communication allows users to carefully craft and optimize their self-presentations (Walther, 1996), and while doing so, increase the likelihood of receiving positive feedback. Finally, the “cue-manageability” affordance offers SNS users the possibility to manage the non-verbal cues that they wish to convey, which, like the asynchonicity affordance, may lead them to present more idealized versions of their self than would be possible in offline settings. This may also increase the likelihood of receiving positive feedback, and, in turn, enhance social self-esteem.

However, not all positive feedback may equally stimulate adolescents' self-esteem. A study by Burke and Kraut (2016) among adults found that the effects of positive feedback depend on both the type of feedback and the closeness of the relationship of the communication partners. Targeted “one-click, low effort” positive feedback, such as likes, from both close friends (named strong ties) and acquaintances (named weak ties) was unrelated to improvements in psychological well-being. Furthermore, “composed” positive feedback (i.e., wall-posts and comments specifically targeted to a person) did show a positive correlation with psychological well-being, but only when it came from close friends (Burke & Kraut, 2016).

In the present study, we investigate whether the mediating role of positive feedback found in previous research exists in both the concurrent and longitudinal relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem. Based on the results of Burke and Kraut (2016), we focus on composed feedback, that is, written feedback on messages or photos posted by SNS users. In addition, we differentiate between feedback from close friends and acquaintances, and expect that only feedback from close friends will act as a mediator between SNS use and social self-esteem. We hypothesize that SNS use has a concurrent (Hypothesis 2a) and longitudinal (Hypothesis 2b) positive effect on social self-esteem through positive feedback from close friends.

2. Method

2.1. Sample and procedure

In order to investigate the aims of the current study, we used three-wave panel survey data. After we received ethical approval from the sponsoring institution's Institutional Review Board, a large, private research institute collected survey data at three time points between September 2012 and December 2014, with one-year intervals. The research institute recruited 516 families with at least two adolescents between 10 and 15 years old. For families with more than two children in this age group, only two participated in the study. Families were recruited in urban and rural regions across The Netherlands. Participants were included in our study if they used an SNS in at least one of the three waves, resulting in 852 adolescents in wave 1 (50.7% girls, Mage = 12.5, SD = 1.36), 783 adolescents in wave 2 (52% girls, Mage = 13.5, SD = 1.34) and 750 adolescents in wave 3 (53.1% girls, Mage = 14.4, SD = 1.35). The attrition rate was 17.5% for wave 2 and 10.0% for wave 3. Adolescents who dropped out in wave 2 used SNSs less frequently, t(851) = 2.88, p = .004, and received less positive feedback from acquaintances at wave 1, t(505) = 2.04, p = .042. They did not differ in social self-esteem, t(851) = 0.33, p = .745, and neither in positive feedback from friends, t(698) = 1.17, p = .242. Adolescents who dropped out in wave 3 did not differ in SNS use, t(775) = 0.47, p = .636, and social self-esteem at wave 2, t(822) = −0.61, p = .541). However, they did receive less positive feedback from friends, t(685) = 2.34, p = .020), and acquaintances, t(521) = 2.17, p = .031 at wave 2. Please note that there were also adolescents who did not use SNS in wave 1 but started using SNS in wave 2 or 3. These individuals could not be included in the attrition analyses.

Before administration of the survey, parental consent and adolescents' informed consent were obtained. We notified adolescents that the survey would be about media and how they feel and act in their daily lives, and that the answers would be analyzed anonymously.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social self-esteem

Social self-esteem was measured with the social acceptance subscale of the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988). In 2012, this subscale was renamed into social self-esteem and its items were slightly adjusted (Harter, 2012b). Our scale consisted of the following four items: “I find it easy to make friends,” “I have a lot of friends,” “I am popular among my peers,” and “It is easy to like me.” Response options were 1 (completely not true), 2 (not true), 3 (a little not true, a little true), 4 (true), and 5 (completely true). We created a scale based on the average of the individual items. Cronbach's alpha of the scale was .82 in wave 1 (M = 3.42, SD = 0.81), .83 in wave 2 (M = 3.42, SD = 0.78), and .86 in wave 3 (M = 3.45, SD = 0.78).

2.2.2. SNS use

Adolescents' frequency of activity on SNSs was measured with five questions, which asked how often adolescents engaged in the following activities on SNSs: (1) “posting messages on your own profile page (e.g., status updates on Facebook), (2) “posting pictures of yourself,” (3) “changing your profile picture,” (4) “reacting to messages that other people have posted on your profile,” and (5) “posting messages on profile pages of others.” Adolescents responded by choosing one of the following options: 1 (almost never), 2 (less than 1 time a week), 3 (2–3 times a week), 4 (every day), 5 (multiple times a day), and 6 (all the time). These items were averaged to create a scale, with higher scores indicating more frequent activity on SNSs. Cronbach's alpha of this measure was .83 in wave 1 (M = 1.98, SD = 0.91), .83 in wave 2 (M = 2.00, SD = 0.88) and .82 in wave 3 (M = 1.91, SD = 0.79).

2.2.3. Positive feedback

The frequency of receiving positive feedback was measured with four items, two about feedback from close friends and two about feedback from acquaintances (“people you don't know very well”). Within each of these two categories we asked about feedback on messages and feedback on photos: “How often do you get positive reactions to messages/photos that you post on SNSs (on your own profile or on another's profile) …” (a) “from close friends,” and (b) “from people you don't know very well?” For all four questions, the response options were: 0 (never), 1 (almost never), 2 (sometimes), 3 (often), and 4 (very often). We created two scales, one for feedback from close friends, and one for feedback from acquaintances. Higher scores on these scales indicated receiving positive feedback more frequently. The alpha for the two-item feedback of close friends scale was .72 in wave 1 (M = 3.53, SD = 0.96), .76 in wave 2 (M = 3.64, SD = 0.90), and .76 in wave 3 (M = 3.79, SD = 0.86). Cronbach's alpha for the two-item feedback from acquaintances scale was .71 in wave 1 (M = 2.84, SD = 0.92), .76 in wave 2 (M = 3.10, SD = 0.95), and .84 in wave 3 (M = 3.19, SD = 0.96). The correlations between the two scales were r = .48 in wave 1, r = .50 in wave 2; and r = .50 in wave 3.

2.3. Data analysis

In order to examine the longitudinal relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem, we tested autoregressive cross-lagged models with three data waves using structural equation modeling in Mplus. Models were estimated using maximum likelihood with robust error estimation (MLR) to correct for the clustered nature of our data (i.e., dependency within our data because of the two adolescents within one family).

We used the root mean square of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR) to assess the models' fit. Generally, RMSEA values smaller than .05 and a CFI/TLI exceeding .95 indicate good model fit, and RMSEA values between .05 and .08 and CFI/TLI values between .90 and .95 indicate acceptable model fit (Byrne, 2001). In addition, SRMR values close to .08 indicate acceptable model fit, and values below .08 indicate good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

3. Results

3.1. Bivariate relationships

Table 1 shows the cross-sectional correlations between all study variables. The correlations between SNS use and social self-esteem were positive in all three data waves. Furthermore, both the correlations between SNS use and the two types of feedback, and those between the two types of feedback and self-esteem were positive in all three data waves. Sex (being a girl) was negatively related to social self-esteem (except in wave 1), and positively related to SNS use, feedback from friends, and feedback from acquaintances (except for wave 2 and 3). Finally, age was not related to self-esteem and inconsistently related to SNS use. Because sex was related to both social self-esteem and SNS use, all subsequent models were controlled for sex.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlation coefficients between all study variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SSE (w 1) | ||||||||||||

| 2. SSE (w 2) | .62∗∗∗ | |||||||||||

| 3. SSE (w 3) | .51∗∗∗ | .63∗∗∗ | ||||||||||

| 4. SNS (w 1) | .25∗∗∗ | .19∗∗∗ | .15∗∗∗ | |||||||||

| 5. SNS (w 2) | .24∗∗∗ | .22∗∗∗ | .19∗∗∗ | .50∗∗∗ | ||||||||

| 6. SNS (w 3) | .23∗∗∗ | .21∗∗∗ | .24∗∗∗ | .35∗∗∗ | .56∗∗∗ | |||||||

| 7. FBF (w 1) | .32∗∗∗ | .17∗∗∗ | .09∗ | .34∗∗∗ | .18∗∗∗ | .06 | ||||||

| 8. FBF (w 2) | .24∗∗∗ | .28∗∗∗ | .25∗∗∗ | .14∗∗∗ | .27∗∗∗ | .18∗∗∗ | .33∗∗ | |||||

| 9. FBF (w 3) | .24∗∗∗ | .27∗∗∗ | .32∗∗∗ | .15∗∗ | .20∗∗∗ | .29∗∗∗ | .18∗∗∗ | .35∗∗∗ | ||||

| 10. FBO (w 1) | .18∗∗∗ | .06 | .08 | .25∗∗∗ | .11∗ | .07 | .48∗∗∗ | .17∗∗∗ | .19∗∗∗ | |||

| 11. FBO (w 2) | .13∗∗∗ | .16∗∗∗ | .12∗∗ | .15∗∗∗ | .12∗∗ | .06 | .29∗∗∗ | .50∗∗ | .24∗∗∗ | .28∗∗∗ | ||

| 12. FBO (w 3) | .24∗∗∗ | .20∗∗∗ | .21∗∗∗ | .18∗∗∗ | .19∗∗∗ | .16∗∗∗ | .20∗∗∗ | .24∗∗∗ | .50∗∗∗ | .27∗∗∗ | .30∗∗∗ | |

| 13. Sex(0 = ♂) | −.04 | −.09∗∗ | −.11∗∗∗ | .19∗∗∗ | .19∗∗∗ | .21∗∗∗ | .16∗∗∗ | .13∗∗ | .23∗∗∗ | .09∗ | .04 | .06 |

Note. ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001 (two-tailed). SSE = social self-esteem; SNS = SNS use; FBF = feedback from friends; FBO = feedback from others (acquaintances); w = data wave.

3.2. Longitudinal relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem

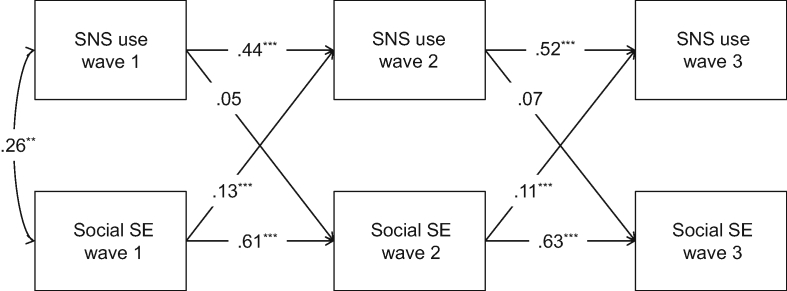

In order to investigate the longitudinal relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem, we tested a cross-lagged model that included adolescents' SNS use and social self-esteem at the three waves (see Fig. 1). The model had an acceptable fit (RMSEA = .08, 95% CI: .06, .11, CFI = .98, TLI: .88, SRMR = .02). Hypothesis 1a predicted that SNS use would have a positive effect on social self-esteem. Standardized betas (βs) showed that SNS use did not significantly increase social self-esteem from wave 1 to wave 2 (β = .05, p = .099, 95% CI: −0.01, .10), and neither from wave 2 to wave 3 (β = .07, p = .076, 95% CI: −0.01, .14), although both p-values were one-tailed significant (p = .050 and p = .038, respectively). Consistent with Hypothesis 1b, social self-esteem increased SNS use over time, both from wave 1 to wave 2 (β = .13, p < .001, 95% CI: .07, .20), and from wave 2 to wave 3 (β = .11, p = .002, 95% CI: .04, .19).

Fig. 1.

The Cross-Lagged Longitudinal Relationships between SNS Use and Social Self-Esteem ∗∗p < .01; ∗∗∗p < .001.

3.3. Indirect effects through positive feedback

Our second hypothesis (H2a for the concurrent and H2b for the longitudinal relationships) stated that positive feedback from close friends would mediate the relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem. We ran separate analyses for positive feedback from friends and from acquaintances.

3.3.1. Concurrent mediation analysis

In a first step, we investigated whether positive feedback mediated the concurrent relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem. To investigate Hypothesis 2a, we tested the direct and indirect effects per wave in separate models. In the concurrent models including positive feedback from friends, all three waves showed a significant indirect effect (wave 1: β = .10, p < .001, 95% CI: .07, .13, wave 2: β = .07, p < .001, 95% CI: .04, .10, wave 3: β = .09, p < .001, 95% CI: .06, .13). In all three data waves, Hypothesis 2a was supported.

Contrary to our expectations, in the model with positive feedback from acquaintances, the indirect effect from SNS use to self-esteem through positive feedback was also significant in all three data waves (wave 1: β = .03, p = .023, 95% CI: .01, .06, wave 2: β = .02, p = .049, 95% CI: .00, .04, wave 3: β = .04, p = .002, 95% CI: .01, .06).

3.3.2. Longitudinal mediation analyses

Although we did not find a consistent direct longitudinal relationship between SNS use and social self-esteem, SNS use could still indirectly predict self-esteem through positive feedback. Therefore, to investigate Hypothesis 2b, we examined a cross-lagged model that included SNS use, social self-esteem, and positive feedback, each measured at all three waves. In this model, we specifically investigated the indirect effect of SNS use at wave 1 on social self-esteem at wave 3 through positive feedback at wave 2. Again, separate models were run for positive feedback from close friends and acquaintances.

The model with positive feedback from close friends had an acceptable fit (RMSEA = .07 [95% CI: .05, .09], CFI = .98, TLI = .87, SRMR = .05). SNS use at wave 1 was not significantly related to positive feedback from friends at wave 2 (β = −0.01, p = .713, 95% CI: −0.09, .06). However, positive feedback from close friends at wave 2 was significantly related to social self-esteem at wave 3 (β = .10, p = .009, 95% CI: .03, .18). The longitudinal indirect effect of SNS use on social self-esteem through positive feedback from close friends was not significant (β = −0.001, p = .713, 95% CI: −0.01, .01).

The model with positive feedback from acquaintances had an acceptable fit (RMSEA = .08 (CI: .06, .09), CFI = .95, TLI = .84, SRMR = .06). SNS use at wave 1 was not significantly related to positive feedback from acquaintances at wave 2 (β = .05, p = .304, 95% CI: −0.01, .15). In addition, positive feedback from acquaintances at wave 2 was not related to social self-esteem at wave 3 (β = .07, p = .102, 95% CI: −0.04, .14). The longitudinal indirect effect of SNS use on self-esteem through positive feedback from acquaintances was not significant (β = .003, p = .386, 95% CI: −0.01, .01).

4. Discussion

Consistent with previous studies we found positive concurrent relationships between adolescents' SNS use and their social self-esteem, which held in all three data waves. However, contrary to our Hypothesis 1a, we did not find decisive longitudinal evidence that adolescents' SNS use increases their social self-esteem. In both the wave 1–2 and the wave 2–3 lags, we found small positive longitudinal relationships (β = .05 and .07) between SNS use and social self-esteem that were only one-tailed significant. In contrast, in both the wave 1–2 and wave 2–3 lags, we found significant and stronger support for our reverse Hypothesis 1b that adolescents' social self-esteem increases their SNS use.

The differences in sizes of the two opposite cross-lagged paths between SNS use and social self-esteem may be due to differences in the trait-state nature of SNS use and social self-esteem. The standard assumption in the social sciences is that personality traits like self-esteem are the predisposing causes and that certain behaviors, like SNS use, are the result. This assumption also underlies Liu and Baumeister's (2016) meta-analysis on the relationship between self-esteem and SNS use among adults. However, although developing a stable self-esteem (i.e., a self-esteem that is less susceptible to environmental influences) is an important task in adolescence, in this turbulent period, self-esteem can fluctuate considerably due to environmental influences, and most notably peer interactions (Harter, 2012a, Rosenberg, 1986). Therefore, reciprocal cross-lagged effects between SNS use and social self-esteem may be more plausible in adolescence than in adulthood.

However, the differences in cross-lagged effects can also be explained methodologically. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the stability coefficients for social self-esteem (β = .61; β = .63) are higher than those of SNS use (β = .44; β = .52). These differences may explain why the cross-lagged effects from social self-esteem to SNS use were higher than those from SNS use to social self-esteem. As in standard cross-lagged analyses, our two outcomes (SNS use and social self-esteem) were controlled for previous levels of these outcomes. This implies that social self-esteem (a high-stability outcome) is better explained by its equivalents in previous data waves than SNS use (a lower-stability outcome). As a consequence, social self-esteem inevitably has less variance left to explain for the cross-lagged predictors. Therefore, as argued by Adachi and Willoughby (2015), even very small cross-lagged effects should be considered meaningful when there is strong stability in the outcome variable and a moderate correlation between the predictor and the outcome as measured at wave 1, as is the case in the present study. After all, unlike concurrent relationships, cross-lagged effects indicate change in the level of the outcome, and such change may reflect an ongoing cumulative effect that could become substantial over time.

4.1. Feedback as an underlying mechanism

Consistent with earlier research and our Hypothesis 2a, the concurrent relationships between SNS use and social self-esteem could be fully explained by the amount of positive feedback that adolescents received on SNSs. However, unlike our expectations and the results of Burke and Kraut (2016), who found that only feedback from strong ties led to improvements in well-being, in the current study the explanatory power of feedback held for both close friends and acquaintances. This may be due to the differences in SNS use between adolescents and adults. First, the online social network of adolescents may be more homogeneous than that of adults, as the majority of adolescents use social media primarily to communicate with their close friends and classmates (Valkenburg & Peter, 2011). Second, most adolescent typically receive positive feedback from these existing friends (Koutamanis et al., 2015, Valkenburg et al., 2006), which may lead to improvements rather than declines in their social self-esteem.

However, contradictory to our Hypothesis 2b, the positive feedback that adolescents received from their close friends did not explain the hypothesized longitudinal relationships between SNS use and self-esteem. This result suggests that feedback may be a more valid mechanism to explain short-term rather than the long-term effects of SNS-use on self-esteem. This is conceivable given that SNSs are designed to elicit instant positive feedback (e.g., through likes or favorites), which may lead to instant (rather than longitudinal) increases self-esteem. This does not alter the fact that SNS use may result in longer-term changes in self-esteem, but it implies that if this occurs, it will be through an accumulation of multiple short-time increases in self-esteem through receiving positive feedback. Future research should further investigate the potential cumulative reciprocal relationships between SNS use and social and global self-esteem.

4.2. Explanations, limitations and future research

This study provided the first longitudinal results on the relationship between SNS use and social self-esteem among adolescents. It found that adolescents high in social self-esteem showed an increase in SNS use in subsequent waves, and that SNS use resulted in small improvements in self-esteem. This reciprocal process can be explained by the rich-get-richer hypothesis (Kraut et al., 2002, Valkenburg and Peter, 2011), which states that adolescents who are extraverted and who are at ease in social situations are especially likely to use social media. It is plausible that this rich-get-richer effect also holds for the relationship between SNS use social self-esteem: Adolescents high in self-esteem may be less hesitant to communicate online and share positive information about themselves, and by doing so enhance the likelihood that they receive positive feedback, which further boost their self-esteem. Such processes may also be explained by a phenomenon that has been called disposition-content congruity (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013): Certain dispositions (e.g., a high social self-esteem) can predispose individuals to use certain media content or technologies, which in turn can reinforce these dispositions. Future research should elaborate on our findings and identify the specific conditions under which SNS use and online feedback may or may not affect adolescents' (and adults') self-esteem. In addition, future research should pay closer attention to the effects of different types of SNS use, since the meta-analysis of Liu and Baumeister suggests that different indicators of SNS use (e.g., frequency versus number of friends) result in opposite correlations with global self-esteem.

In line with several earlier studies, we predicted that the positivity bias on SNSs, that is, the tendency of SNS users to share positive rather than negative information about themselves, would elicit reciprocal positive feedback from receivers, which, in turn, would lead to improvements in social self-esteem. Both the positivity bias (Reinecke & Trepte, 2014) and the tendency to respond to such messages with positive feedback (Burke & Develin, 2016) have been verified in empirical research. However, this same positivity bias on SNSs may also lead to decreases in social self-esteem through another mechanism, that is, upward social comparison, defined as the tendency of some SNS users to compare themselves to other users who are perceived to be more beautiful or successful than they are. Unfortunately, the current study failed to investigate the validity of upward comparison. But several other studies have confirmed that the tendency towards upward comparison may lead to decreases in social (de Vries & Kühne, 2015), physical (Haferkamp and Krämer, 2010, de Vries and Kühne, 2015), and global self-esteem (Lee, 2014, Vogel et al., 2014).

All in all, there seem to be two different explanatory mechanisms that both result from the positivity bias on SNSs, and that both can influence self-esteem, albeit in different directions. Up to now, it seems that studies on feedback have mostly focused on the effects of positive feedback on improvements in self-esteem, whereas studies focusing on social comparison have mainly focused on the effects of upward social comparisons on declines in self-esteem. However, in both strands of research there is also evidence of opposite effects, albeit less visible. For example, the self-esteem of the minority of adolescents who mainly get negative feedback while using SNSs is likely to suffer from this feedback (Valkenburg et al., 2006). Likewise, downward (rather than upward) comparisons on SNSs do not seem to predict changes in global self-esteem (Vogel et al., 2014). Therefore, there is vital need for future research to reconcile and make sense of these seemingly contradictory findings in these different strands of literature.

These diverging results strongly imply that it is not SNS use per se that leads to positive or negative effects on self-esteem among adolescents, but rather the specific ways in which SNSs are used and by whom. In other words, it is the particular behavior of adolescents that enhances the likelihood to experience certain positive or negative effects. For example, receiving negative feedback is significantly predicted by risky online behavior and a tendency to initiate contact with unknown others (Koutamanis et al., 2015). Negative feedback is also related to low inhibitory control, high sensation seeking, peer problems, and family conflict (Koutamanis et al., 2015). Furthermore, the effects of upward comparisons on social and physical self-esteem are significantly weaker for users who are satisfied with their life (de Vries & Kühne, 2015), and those who have a low inclination to upward comparisons (Lee, 2014).

Adolescents' personality traits and their specific online behavior largely predict which online mechanisms hold for them, and which outcomes they experience from their online behavior. It is evident that parents and educators can play a critical role in enhancing the positive effects of SNS use and combatting the negative ones. After all, helping adolescents prevent systematic and enduring negative online feedback and explaining to them that the social media world may not be as beautiful as it often appears, seem to be important components of today's media-specific parenting (Valkenburg, Piotrowski, Hermanns, & de Leeuw, 2013). Social media have become a main ingredient of adolescents' social lives. This study has attempted to shed more light on one of the mechanisms that may explain positive and negative effects of SNS use. Knowledge about such mechanisms is of vital importance for the design of prevention and intervention strategies within the family and formal media literacy programs. After all, only if we know which mechanisms may lead to certain outcomes of SNS use among certain adolescents, are we able to adequately target prevention and intervention strategies at these adolescents.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a grant to the first author from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no [AdG09 249488-ENTCHILD].

Contributor Information

Patti M. Valkenburg, Email: p.m.valkenburg@uva.nl.

Maria Koutamanis, Email: maria.koutamanis@gmail.com.

Helen G.M. Vossen, Email: h.g.m.vossen@uu.nl.

References

- Adachi P., Willoughby T. Interpreting effect sizes when controlling for stability effects in longitudinal autoregressive models: Implications for psychological science. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2015;12(1):116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Apaolaza V., Hartmann P., Medina E., Barrutia J.M., Echebarria C. The relationship between socializing on the Spanish online networking site Tuenti and teenagers' subjective wellbeing: The roles of self-esteem and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(4):1282–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F., Campbell J.D., Krueger J.I., Vohs K.D. Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2003;4(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/1529-1006.01431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova N.N., Choi Y.H., Sosik V.S., Cosley D., Whitlock J. Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. 2015. Social sharing of emotions on Facebook: Channel differences, satisfaction, and replies; pp. 154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Blomfield Neira C.J., Barber B.L. Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents' social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2014;66(1):56–64. [Google Scholar]

- boyd d. Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics and implications. In: Papacharissi Z., editor. A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites. Routledge; New York, NJ: 2011. pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Burke M., Develin M. Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. 2016. Once more with feeling: Supportive responses to social sharing on Facebook; pp. 1462–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Burke M., Kraut R.E. The relationship between Facebook use and well-being depends on communication type and tie strength. Journal of Computer-mediated Communication. 2016;21(4):265–281. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne B.M. Vol. 2. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. (Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming). [Google Scholar]

- Elkind D., Bowen R. Imaginary audience behavior in children and adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15(1):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti G., Dèttore D., Casale S. Adolescent Internet addiction: Testing the association between self-esteem, the perception of Internet attributes, and preference for online social interactions. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2012;15(6):318–323. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2011.0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greitemeyer T., Mügge D.O., Bollermann I. Having responsive Facebook friends affects the satisfaction of psychological needs more than having many Facebook friends. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2014;36(3):252–258. [Google Scholar]

- Gross E.F. Logging on, bouncing back: An experimental investigation of online communication following social exclusion. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(6):1787–1793. doi: 10.1037/a0016541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferkamp N., Krämer N.C. Social comparison 2.0: Examining the effects of online profiles on social networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2010;14(5):309–314. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1988. Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Guilford; New York, NJ: 2012. The construction of the self: Developmental and sociocultural foundations. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 2012. Manual for the self-perception profile for adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S., Whitesell N.R., Junkin L.J. Similarities and differences in domain-specific and global self-evaluations of learning-disabled, behaviorally disordered, and normally achieving adolescents. American Educational Research Journal. 1998;35(4):653–680. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L.A., Zhao Y., Witt E.A., Fitzgerald H.E., von Eye A., Harold R. Self-concept, self-esteem, gender, race, and information technology use. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2010;12(4):437–440. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2008.0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutamanis M., Vossen H.G.M., Valkenburg P.M. Adolescents' comments in social media: Why do adolescents receive negative feedback and who is most at risk? Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;53:486–494. [Google Scholar]

- Kraut R., Kiesler S., Boneva B., Cummings J., Helgeson V., Crawford A. Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues. 2002;58(1):49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.Y. How do people compare themselves with others on social network sites? The case of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;32:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Baumeister R.F. Social networking online and personality of self-worth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality. 2016;64:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H.W., Craven R.G. Reciprocal effects of self-concept and performance from a multidimensional perspective: Beyond seductive pleasure and unidimensional perspectives. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2006;1(2):133–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dea B., Campbell A. Online social networking amongst teens: Friend or foe. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2011;167:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke L., Trepte S. Authenticity and well-being on social network sites: A two-wave longitudinal study on the effects of online authenticity and the positivity bias in SNS communication. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;30:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Self-concept and psychological well-being in adolescence. In: Leahy R.L., editor. The development of the self. Academic Press; Olando, FL: 1986. pp. 205–246. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt K.L., Dayanim S., Matthias S. Personal homepage construction as an expression of social development. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(2):496–506. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaes S., Reijntjes A., Orobio de Castro B., Bushman B.J., Poorthuis A., Telch M.J. I like me if you like me: On the interpersonal modulation and regulation of preadolescents' state self-esteem. Child Development. 2010;81(3):811–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M. Understanding self-effects in social media. Human Communication Research. 2017;43(3) [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J. Online communication among adolescents: An integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(2):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J. The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication. 2013;63(2):221–243. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Peter J., Schouten A.P. Friend networking sites and their relationship to adolescents' well-being and social self-esteem. Cyberpsychology & Behavior. 2006;9(5):584–590. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Piotrowski J.T. Yale University Press; New Haven, NJ: 2017. Plugged in: How media attract and affect youth. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg P.M., Piotrowski J.T., Hermanns J., de Leeuw R. Developing and validating the perceived parental media mediation scale: A self-determination perspective. Human Communication Research. 2013;39(4):445–469. [Google Scholar]

- van den Eijnden R.J.J.M., Lemmens J.S., Valkenburg P.M. The social media disorder scale. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;61:478–487. [Google Scholar]

- van der Aa N., Overbeek G., Engels R.C., Scholte R.H., Meerkerk G.-J., van den Eijnden R.J. Daily and compulsive internet use and well-being in adolescence: A diathesis-stress model based on big five personality traits. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(6):765–776. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel E.A., Rose J.P., Roberts L.R., Eckles K. Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 2014;3(4):206–222. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries D.A., Kühne R. Facebook and self-perception: Individual susceptibility to negative social comparison on Facebook. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;86:217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Walther J.B. Computer-mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research. 1996;23(1):3–43. [Google Scholar]