Abstract

Background

As an invasive malignant tumor, osteosarcoma (OS) has high mortality. Parathyroid hormone receptor 1 (PTHR1) contributes to maintaining proliferation and undifferentiated state of OS. This study is designed to reveal the action mechanisms of PTHR1 in OS.

Methods

Microarray dataset GSE46861, which included six PTHR1 knockdown OS samples and six control OS samples, was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified and then performed with enrichment analysis separately using the limma package and DAVID online tool. Then, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and module analyses were conducted using Cytoscape software. Using the WebGestalt tool, microRNAs (miRNAs) were predicted for the DEGs involved in the PPI network. Following this, transcription factors (TFs) were predicted and an integrated network was constructed by Cytoscape software.

Results

There were 871 DEGs in the PTHR1 knockdown OS samples compared with the control OS samples. Besides, upregulated ZFPM2 was involved in the miRNA-DEG regulatory network. Moreover, TF LEF1 was predicted for the miRNA-DEG regulatory network of the downregulated genes. In addition, LEF1, NR4A2, HAS2, and RHOC had higher degrees in the integrated network.

Conclusions

ZFPM2, LEF1, NR4A2, HAS2, and RHOC might be potential targets of PTHR1 in OS.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma, Parathyroid hormone receptor 1, Differentially expressed genes, Protein-protein interaction network, Integrated network

Background

As an invasive malignant tumor, osteosarcoma (OS) often occurs in tubular long bones [1]. OS is the most common type of primary bone cancer, which has high occurrence rate in children and teenagers [2]. OS has rapid growth, high metastatic potential, and local aggressiveness; thus, it can result in high mortality [3]. In childhood cancers, OS accounts for about 2.4% of all malignant cancers and is the eighth most common tumor [4]. Therefore, revealing the molecular mechanisms of OS and developing novel therapies are of great importance.

Via upregulating matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), astrocyte elevated gene 1 (AEG1) functions in OS progression can be used for predicting the progression and prognosis of the disease [5, 6]. A previous study reports that miR-203 is a tumor suppressor by mediating RAB22A, member RAS oncogene family (RAB22A) expression, and has correlation with the progression and carcinogenesis of OS [7]. Through nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway and mitochondria pathway, the inhibitor of growth 4 (ING4) plays a suppressive role in OS progression and serves as a potential target for treating OS [8, 9]. miR-24 inhibits the metastasis of OS via regulating activated Cdc42-associated kinase (ACK1) through AKT/MMP pathways, which may be applied for the diagnosis and therapy of OS [10]. However, the pathogenesis of OS has not been comprehensively revealed.

Parathyroid hormone receptor 1 (PTHR1) signaling plays a critical role in keeping proliferation and undifferentiated state of OS; thus, PTHR1 suppression may be used to inhibit OS proliferation and promote differentiation [11, 12]. Overexpression of PTHR1 may contribute to OS progression through affecting aggressive phenotype and microenvironment [13]. To explore the action mechanisms of PTHR1 in OS, we downloaded the microarray dataset GSE46861 which included both PTHR1 knockdown OS samples and control OS samples. Then, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified and performed with enrichment analysis. In addition, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and module analyses, as well as integrated network analysis, were conducted to further screen the key targets of PTHR1 in OS.

Methods

Data source and data preprocessing

Microarray dataset GSE46861, which was sequenced on the platform of GPL6246 [MoGene-1_0-st] Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array [transcript (gene) version], was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database. GSE46861 included six PTHR1 knockdown OS samples and six control OS samples. The raw data of GSE46861 was normalized using the Robust Multiarray Average (RMA) method [14] in the R package Affy (version: 1.52.0).

DEG screening and hierarchical cluster analysis

After the data normalization, the DEGs between PTHR1 knockdown OS samples and control OS samples were screened using the Linear Models for Microarray Analysis (limma, version: 3.30.3) [15] package in R. The |log2 fold change (FC)| > 0.58 and p value < 0.05 were considered as the thresholds. In addition, pheatmap package (version 1.0.8, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html) in R was utilized to perform the hierarchical cluster analysis.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) database can annotate genes and gene products from molecular function (MF), biological process (BP), and cellular component (CCo) aspects [16]. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database can be applied for revealing gene functions and connecting genomic information with functional information [17]. Using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, version: 6.8, parameter: Classification Stringency was set as Medium) online tool [18], GO functional and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses were carried out for the DEGs, with the threshold of p value < 0.05.

PPI network and module analyses

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, version: 10.0) database [19], which included PPI pairs of multiple organisms, was used to analyze the PPI pairs among the DEGs. The required confidence (combined score) > 0.4 was used as the cutoff criterion. Afterwards, PPI network was visualized using Cytoscape software [20]. Based on the CytoNCA plugin (version 2.1.6, parameter: without weight) [21] in Cytoscape software, topological property analysis was performed for the nodes in the PPI network. According to closeness centrality (CCe), betweenness centrality (BC), and degree centrality (DC) scores, the hub nodes [22] in the PPI network were selected. Moreover, the MCODE plugin (version 1.2) [23] in Cytoscape software was used for identifying the significant modules in the PPI network. In addition, enrichment analysis for the genes involved in the most significant module was conducted using the DAVID online tool [18].

Integrated network analysis

Using WEB-based gene set analysis toolkit (WebGestalt) tool [24], miRNAs were predicted for the DEGs involved in the PPI network, with false discovery rate (FDR, that was adjusted p value) < 0.05 and number of target genes ≥ 5 as the thresholds. Based on the iRegulon plugin (version 1.3) [25] in Cytoscape software, transcription factors (TFs) were further predicted for the miRNA-DEG regulatory network. The Minimum NEScore > 3 and FDR on motif similarity < 0.001 were set as thresholds. Finally, the obtained transcription regulation relationships were merged into the miRNA-DEG regulatory network, and the integrated network was visualized by Cytoscape software [20].

Results

DEG analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis

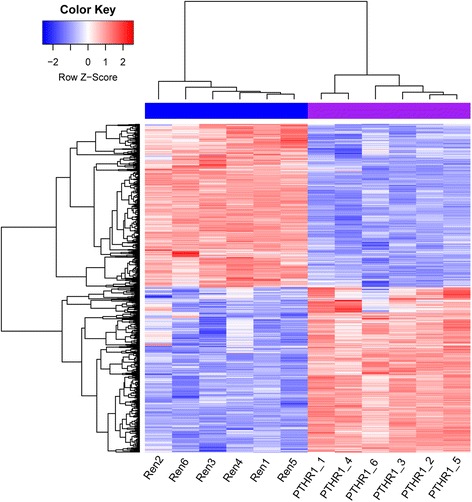

Compared with the control OS samples, there were a total of 871 DEGs (438 upregulated and 433 downregulated genes) in the PTHR1 knockdown OS samples. The heatmap of the DEGs is shown in Fig. 1, which indicated that the expression of identified DEGs could correctly distinguish the two kinds of samples.

Fig. 1.

The heatmap of the differentially expressed genes by using pheatmap package

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

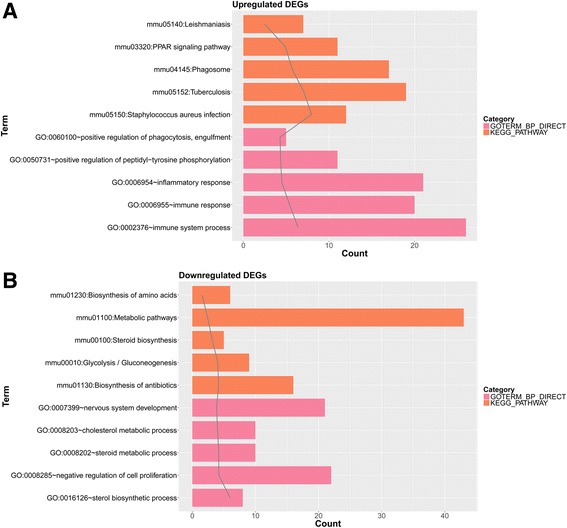

Enrichment analysis was conducted for the upregulated genes and the downregulated genes, respectively. A total of 121 GO_BP terms and 20 pathways were enriched for the upregulated genes. The top five GO_BP terms and pathways are shown in Fig. 2a, mainly including immune system process (GO_BP, p value = 4.07E−07) and Staphylococcus aureus infection (pathway, p value = 1.09E−08). Besides, a total of 65 GO_BP terms and five pathways were enriched for the downregulated genes. Similarly, the top five GO_BP terms (such as sterol biosynthetic process, p value = 1.02E−06) and pathways (such as Biosynthesis of antibiotics, p value = 6.96E−05) are shown in Fig. 2b.

Fig. 2.

The top five GO_BP terms and pathways for the upregulated genes (a) and the downregulated genes (b), respectively, analyzed by Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery online tool. GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

PPI network and module analyses

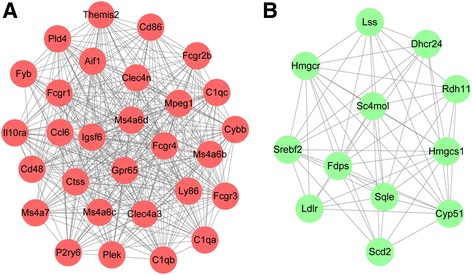

The PPI network for the upregulated genes had 280 nodes and 1090 interactions. According to DC scores, the nodes with degrees larger than 30 are listed in Table 1. The most significant module (score = 25.786) identified from the PPI network for the upregulated genes had 29 nodes and 361 interactions (Fig. 3a). The upregulated genes involved in the most significant module were mainly enriched in immune system process (GO_BP, p value = 1.63E−07) and Staphylococcus aureus infection (pathway, p value = 2.59E−10) (Table 2 (A)).

Table 1.

The nodes with degrees larger than 30 in the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network for the upregulated genes

| Gene | Degree | Betweenness | Closeness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ms4a6d | 41.0 | 888.54470 | 0.055844676 |

| Ly86 | 39.0 | 523.09924 | 0.055800000 |

| Ms4a6b | 39.0 | 2949.2993 | 0.055755395 |

| C1qb | 38.0 | 1383.42100 | 0.055766540 |

| C1qa | 38.0 | 3947.00420 | 0.056295400 |

| Aif1 | 37.0 | 4212.39100 | 0.056261342 |

| Mpeg1 | 37.0 | 323.91983 | 0.055655297 |

| Fcgr1 | 37.0 | 501.60864 | 0.055633100 |

| Ctss | 37.0 | 640.59326 | 0.055588763 |

| C1qc | 37.0 | 749.12880 | 0.055811163 |

| Clec4a3 | 36.0 | 475.66116 | 0.055710863 |

| Gpr65 | 36.0 | 998.11590 | 0.055822328 |

| Igsf6 | 34.0 | 173.94502 | 0.055544496 |

| Fcgr3 | 34.0 | 1279.76680 | 0.055811163 |

| Cd86 | 33.0 | 2105.79080 | 0.055710863 |

| Themis2 | 33.0 | 415.82825 | 0.055577688 |

| Fcgr4 | 33.0 | 310.27353 | 0.055500300 |

| Ms4a6c | 33.0 | 146.86868 | 0.055566620 |

| Cybb | 33.0 | 5207.74660 | 0.056695793 |

| Ccl6 | 32.0 | 927.98834 | 0.055721990 |

| Clec4n | 31.0 | 164.47343 | 0.055555556 |

Fig. 3.

The most significant modules identified from the protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks for the upregulated genes (a) and the downregulated genes (b). The significant modules were analyzed by using MCODE plugin, and then module networks were visualized using Cytoscape software

Table 2.

The GO_BP terms and pathways enriched for the upregulated genes (A) and the downregulated genes (B) involved in the most significant modules. GO, Gene Ontology; BP, biological process

| Category | Term | Count | P value | Gene symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||||

| GO_BP | GO:0002376~immune system process | 8 | 1.63E−07 | C1QA, C1QB, CD86, LY86, FCGR1, THEMIS2, C1QC, CLEC4N |

| GO:0045576~mast cell activation | 4 | 3.83E−07 | CD48, FYB, FCGR2B, FCGR3 | |

| GO:0045087~innate immune response | 7 | 4.62E−06 | C1QA, C1QB, CYBB, LY86, FCGR1, C1QC, CLEC4N | |

| GO:0006911~phagocytosis, engulfment | 4 | 1.86E−05 | FCGR2B, AIF1, FCGR1, FCGR3 | |

| GO:0006954~inflammatory response | 5 | 5.96E−04 | CYBB, AIF1, LY86, THEMIS2, CCL6 | |

| PATHWAY | mmu05150:Staphylococcus aureus infection | 7 | 2.59E−10 | C1QA, C1QB, FCGR2B, FCGR4, FCGR1, C1QC, FCGR3 |

| mmu05322:Systemic lupus erythematosus | 6 | 6.02E−06 | C1QA, C1QB, CD86, FCGR4, FCGR1, C1QC | |

| mmu04145:Phagosome | 6 | 1.37E−05 | CYBB, FCGR2B, FCGR4, CTSS, FCGR1, FCGR3 | |

| mmu05152:Tuberculosis | 6 | 1.45E−05 | FCGR2B, IL10RA, FCGR4, CTSS, FCGR1, FCGR3 | |

| mmu04380:Osteoclast differentiation | 5 | 8.03E−05 | CYBB, FCGR2B, FCGR4, FCGR1, FCGR3 | |

| (B) | ||||

| GO_BP | GO:0016125~sterol metabolic process | 8 | 4.60E−14 | CYP51, LDLR, HMGCR, FDPS, HMGCS1, SREBF2, SC4MOL, DHCR24 |

| GO:0008202~steroid metabolic process | 9 | 5.23E−14 | CYP51, LDLR, HMGCR, FDPS, HMGCS1, LSS, SREBF2, SC4MOL, DHCR24 | |

| GO:0008203~cholesterol metabolic process | 7 | 6.80E−12 | CYP51, LDLR, HMGCR, FDPS, HMGCS1, SREBF2, DHCR24 | |

| GO:0006694~steroid biosynthetic process | 7 | 7.42E−12 | CYP51, HMGCR, FDPS, HMGCS1, LSS, SC4MOL, DHCR24 | |

| GO:0016126~sterol biosynthetic process | 6 | 1.69E−11 | CYP51, HMGCR, FDPS, HMGCS1, SC4MOL, DHCR24 | |

| PATHWAY | mmu00100:Steroid biosynthesis | 5 | 1.10E−08 | CYP51, SQLE, LSS, SC4MOL, DHCR24 |

| mmu00900:Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis | 3 | 2.46E−04 | HMGCR, FDPS, HMGCS1 | |

Besides, the PPI network constructed for the downregulated genes included 262 nodes and 503 interactions. In the PPI network, discs, large homolog 4 (DLG4) was the only node with degree larger than 20. Module analysis for the PPI network of the downregulated genes showed that the most significant module (score = 10.364) had 12 nodes and 57 interactions (Fig. 3b). The downregulated genes involved in the most significant module were mainly enriched in sterol metabolic process (GO_BP, p value = 4.60E–14) and steroid biosynthesis (pathway, p value = 1.10E−08) (Table 2 (B)).

Integrated network analysis

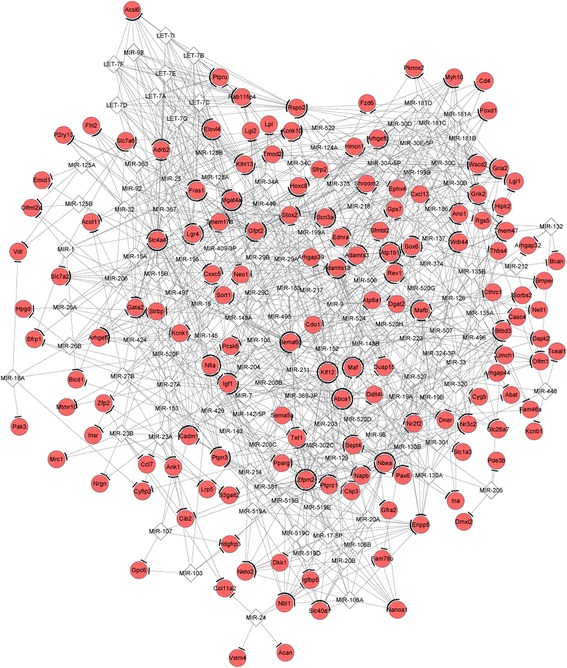

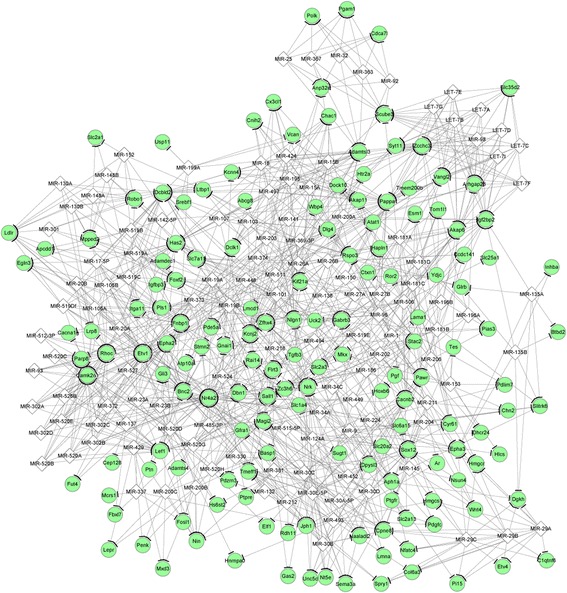

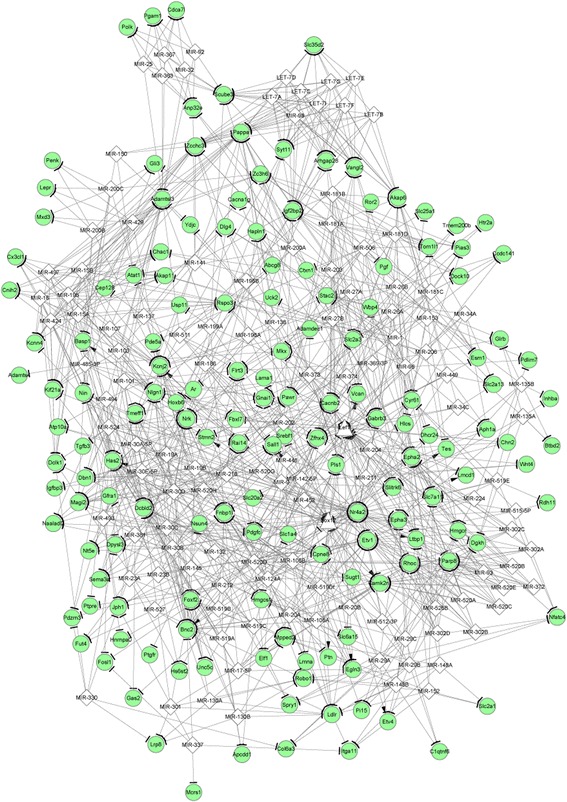

The miRNA-DEG regulatory network constructed for the upregulated genes (such as zinc finger protein, multitype 2, ZFPM2) and the downregulated genes are separately shown in Figs. 4 and 5. There was no TF predicted for the miRNA-DEG regulatory network of the upregulated genes. Only two TFs (SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 12, SOX12, and lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1, LEF1) were predicted for the miRNA-DEG regulatory network of the downregulated genes. The integrated network for the downregulated genes had 278 nodes and 1144 edges (Fig. 6). Especially, LEF1, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 2 (NR4A2), hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS2), and ras homolog family member C (RHOC) had higher degrees in the integrated network.

Fig. 4.

The miRNA-gene regulatory network for the upregulated genes. The interactions of miRNAs-gene were predicted by WEB-based gene set analysis toolkit tool, and regulatory network was visualized using Cytoscape software. Red circles and white quadrangles represent upregulated genes and miRNAs, respectively

Fig. 5.

The miRNA-gene regulatory network for the downregulated genes visualized using Cytoscape software. The interactions of miRNAs-gene were predicted by WEB-based gene set analysis toolkit tool, and regulatory network was visualized using Cytoscape software. Green circles and white quadrangles represent downregulated genes and miRNAs, respectively

Fig. 6.

The integrated network for the downregulated genes visualized by Cytoscape software. The miRNA-gene regulatory relationships in the network were predicted by using WEB-based gene set analysis toolkit tool, whereas transcription factor-genes regulatory relationships in the network were predicted by using iRegulon plugin. Green circles, white quadrangles, and white triangles represent downregulated genes, miRNAs, and transcription factors, respectively

Discussion

In this study, a total of 871 DEGs were identified in the PTHR1 knockdown OS samples compared with the control OS samples, including 438 upregulated and 433 downregulated genes. ZFPM2 was involved in the miRNA-DEG regulatory network constructed for the upregulated genes. There was no TF predicted for the miRNA-DEG regulatory network of the upregulated genes. Besides, TF LEF1 was predicted for the miRNA-DEG regulatory network of the downregulated genes. In the integrated network, LEF1, NR4A2, HAS2, and RHOC had higher degrees.

In rat bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs), neurotrophic factors, NURR1 (also named NR4A2), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), and nestin genes have spontaneous expression [26]. NURR1 and NURR77 may contribute to increase the migratory potential of fetal FBMSCs, which may mediate the local immune response specifically [27]. NURR1 and PPARγ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) may play pivotal roles in mediating osteoblast function and cAMP-dependent osteoblast gene expression [28, 29]. NURR1 maintains cartilage homeostasis via selectively inhibiting the expression of MMP gene during inflammation [30]. These declared that PTHR1 might function in OS through targeting NR4A2.

Hyaluronan synthesized by HAS2 affects the proliferation, invasion, and motility of MG-63 OS cells [31]. Through regulating the expressions of versican, HAS2, and hyaluronan, transforming growth factor β2 (TGF-β2) may lead to the metastasis of OS cells [32]. HAS2 plays critical roles in osteoblast differentiation and development by mediating high molecular weight hyaluronan synthesis [33]. RHOC and MMP9 expression levels have close association, and their high expressions are closely correlated with the formation, development, invasion, and metastasis of OS [34]. RHOC has different expressions in SOSP-9607E10 and SOSP-9607H9 OS cell lines, and its overexpression functions in the invasion and metastasis of OS through inducing cell migration [35]. Therefore, HAS2 and RHOC might also be targets of PTHR1 in OS.

Via regulating the expression of ZFPM2, hypoxia-induced miR-429 contributes to the differentiation of osteoblastic cells [36]. LEF1 can delay osteoblast maturation and regulates the expression levels of some genes in osteoblasts [37]. LEF1 has an essential role in the activation of alpha 1 (XI) collagen (COL11A1), and COL11A1 inhibits the terminal differentiation of osteoblasts [38]. LEF1 serves as a transcriptional effector of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and is critical for the tumor invasion induced by hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [39]. LEF1 mediates bone density, osteoblast differentiation, and skeletal strength, and Lef1ΔN regulates the terminal differentiation in osseous cells [40, 41]. Thus, ZFPM2 and LEF1 might be targets of PTHR1 in OS.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a total of 871 DEGs were screened from the PTHR1 knockdown OS samples. Besides, ZFPM2, LEF1, NR4A2, HAS2, and RHOC might be targets of PTHR1 in OS. However, more experimental researches should be conducted to confirm these findings obtained from bioinformatics analysis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ACK1

Activated Cdc42-associated kinase

- AEG1

Elevated gene 1

- BC

Betweenness centrality

- BMSCs

Bone marrow stromal cells

- BP

Biological process

- CCo

Cellular component

- CCe

Closeness centrality

- DAVID

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

- DC

Degree centrality

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- DLG4

Discs, large homolog 4

- FC

Fold change

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GO

Gene Ontology

- HAS2

Hyaluronan synthase 2

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- ING4

Inhibitor of growth 4

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MF

Molecular function

- MMP2

Matrix metalloproteinase 2

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- NR4A2

Nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 2

- OS

Osteosarcoma

- PGC-1α

PPARγ coactivator-1α

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- PTHR1

Parathyroid hormone receptor 1

- RHOC

Ras homolog family member C

- RMA

Robust Multiarray Average

- STRING

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes

- TFs

Transcription factors

- TGF-β2

Growth factor β2

- TH

Neurotrophic factors, tyrosine hydroxylase.

Authors’ contributions

DG and HT participated in the design of this study, and they both collected important background information, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Both of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Donghui Guan and Honglai Tian are co-first authors.

References

- 1.Luetke A, Meyers PA, Lewis I, Juergens H. Osteosarcoma treatment—where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ottaviani G, Jaffe N, Eftekhari F, Raymond AK, Yasko AW. Pediatric and adolescent osteosarcoma. Berlin: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohseny AB, Tieken C, van der Velden PA, Szuhai K, de Andrea C, Hogendoorn PC, Cleton-Jansen AM. Small deletions but not methylation underlie CDKN2A/p16 loss of expression in conventional osteosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:1095–1103. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:3–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang F, Ke ZF, Sun SJ, Chen WF, Yang SC, Li SH, Mao XP, Wang L. Oncogenic roles of astrocyte elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) in osteosarcoma progression and prognosis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:539–548. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.6.16301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang F, Ke ZF, Wang R, Wang YF, Huang LL, Wang LT. Astrocyte elevated gene-1 (AEG-1) promotes osteosarcoma cell invasion through the JNK/c-Jun/MMP-2 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452:933–939. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang D, Liu G, Wang K. miR-203 acts as a tumor suppressor gene in osteosarcoma by regulating RAB22A. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Mei L, Ye Z, Zhang H, Li L, Peng H, Hong X, Yu Z, Mao C. Delivery of inhibitor of growth 4 (ING4) gene significantly inhibits proliferation and invasion and promotes apoptosis of human osteosarcoma cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7380. doi: 10.1038/srep07380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu M, Xie Y, Sheng W, Miao J, Yang J. Adenovirus-mediated ING4 gene transfer in osteosarcoma suppresses tumor growth via induction of apoptosis and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2015;14:617–26. doi: 10.7785/tcrt.2012.500424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu B, Zhang K. miR-24 represses metastasis of human osteosarcoma cells by targeting Ack1 via AKT/MMPs pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho PW, Goradia A, Russell MR, Chalk AM, Milley KM, Baker EK, Danks JA, Slavin JL, Walia M, Crimeenirwin B. Knockdown of PTHR1 in osteosarcoma cells decreases invasion and growth and increases tumor differentiation in vivo. Oncogene. 2014;34:2922–2933. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho PW, Russell M, Goradia A, Chalk A, Slavin J, Dickins R, Martin TJ, Walkley C. Abstract A54: PTHR1 signaling regulates the invasion and differentiation stage of osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:A54. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.PEDCAN-A54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang R, Hoang BH, Kubo T, Kawano H, Chou A, Sowers R, Huvos AG, Meyers PA, Healey JH, Gorlick R. Over-expression of parathyroid hormone Type 1 receptor confers an aggressive phenotype in osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:943–954. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47–e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Consortium TGO. Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1049–1056. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;44:D457–DD62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang DW. DAVID Bioinformatics Resources: expanded annotation database and novel algorithms to better extract biology from large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING v9. 1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–DD15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saito R, Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang P-L, Lotia S, Pico AR, Bader GD, Ideker T. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang Y, Li M, Wang J, Pan Y, Wu FX. CytoNCA: a cytoscape plugin for centrality analysis and evaluation of protein interaction networks. Bio Systems. 2015;127:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He X, Zhang J. Why do hubs tend to be essential in protein networks? PLoS Genet. 2006;2:826–834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:1–27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Duncan D, Shi Z, Zhang B. WEB-based GEne SeT AnaLysis Toolkit (WebGestalt): update 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:77–83. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Janky RS, Verfaillie A, Imrichová H, Sande BVD, Standaert L, Christiaens V, Hulselmans G, Herten K, Sanchez MN, Potier D. iRegulon: from a gene list to a gene regulatory network using large motif and track collections. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fatemeh M, Maryam HGK, Taghi GM, Taghi L. Spontaneous expression of neurotrophic factors and TH, Nurr1, Nestin genes in long-term culture of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell J. 2012;13:243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maijenburg MW, Gilissen C, Melief SM, Kleijer M, Weijer K, Ten BA, Roelofs H, Van Tiel CM, Veltman JA, de Vries CJ. Nuclear receptors Nur77 and Nurr1 modulate mesenchymal stromal cell migration. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:228–238. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nervina JM, Magyar CE, Pirih FQ, Tetradis S. PGC-1alpha is induced by parathyroid hormone and coactivates Nurr1-mediated promoter activity in osteoblasts. Bone. 2006;39:1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siyahian AJ. PTH and Nurr1 mediated gene expression in osteoblasts. Dissertations & Theses - Gradworks. Los Angeles: University of California; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mix KS, Attur MG, Al-Mussawir H, Abramson SB, Brinckerhoff CE, Murphy EP. Transcriptional repression of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression by the orphan nuclear receptor NURR1 in cartilage. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9492–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishida Y, Knudson W, Knudson CB, Ishiguro N. Antisense inhibition of hyaluronan synthase-2 in human osteosarcoma cells inhibits hyaluronan retention and tumorigenicity. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikitovic D, Zafiropoulos A, Katonis P, Tsatsakis A, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK, Tzanakakis GN. Transforming growth factor-beta as a key molecule triggering the expression of versican isoforms v0 and v1, hyaluronan synthase-2 and synthesis of hyaluronan in malignant osteosarcoma cells. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:47–53. doi: 10.1080/15216540500531713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falconi D, Aubin JE. LIF inhibits osteoblast differentiation at least in part by regulation of HAS2 and its product hyaluronan. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1289–300. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du HZ, Liu XM, Zhang YX. Expression of RhoC and MMP-9 in osteosarcoma and its clinicopathological significance. Mod Prev Med. 2010;37:1794–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang CY, Jiang-Dong NI. Molecular mechanisms of RhoC inducing invasion and metastasis of osteosarcoma. J Clin Res. 2007;24:1639–43. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang J, Peng J, Cao G, Lu S, Liu L, Li Z, Zhou M, Feng M, Shen H. Hypoxia-induced MicroRNA-429 promotes differentiation of MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells by mediating ZFPM2 expression. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39:1177–1186. doi: 10.1159/000447824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahler RA, Galindo M, Lian J, Stein GS, van Wijnen AJ, Westendorf JJ. Lymphocyte enhancer-binding factor 1 (Lef1) inhibits terminal differentiation of osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:969–83. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kahler RA, Yingst SM, Hoeppner LH, Jensen ED, Krawczak D, Oxford JT, Westendorf JJ. Collagen 11a1 is indirectly activated by lymphocyte enhancer-binding factor 1 (Lef1) and negatively regulates osteoblast maturation. Matrix Biol. 2008;27:330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang FI, Chen YL, Chang CN, Yuan RH, Jeng YM. Hepatocyte growth factor activates Wnt pathway by transcriptional activation of LEF1 to facilitate tumor invasion. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1142–1148. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoeppner LH, Secreto F, Jensen ED, Li X, Kahler RA, Westendorf JJ. Runx2 and bone morphogenic protein 2 regulate the expression of an alternative Lef1 transcript during osteoblast maturation. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221:480–489. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galindo M, Kahler RA, Teplyuk NM, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS, Westendorf JJ, van Wijnen AJ. Cell cycle related modulations in Runx2 protein levels are independent of lymphocyte enhancer-binding factor 1 (Lef1) in proliferating osteoblasts. J Mol Histol. 2007;38:501–506. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.