Summary

Gas fermentation is a microbial process that contributes to at least four of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) of the United Nations. The process converts waste and greenhouse gases into commodity chemicals and fuels. Thus, world's climate is positively affected. Briefly, we describe the background of the process, some biocatalytic strains, and legal implications.

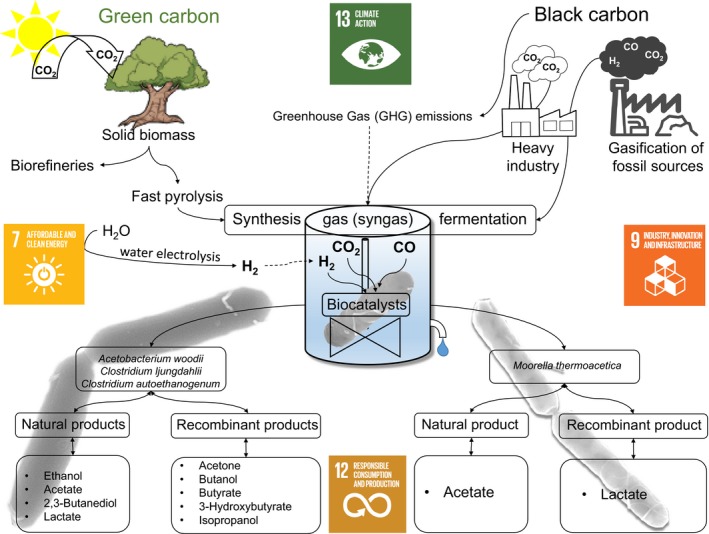

Currently, two of the greatest challenges facing industry and society are the future sustainable production of chemicals and fuels from non‐food resources while at the same time reducing Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The whole world needs to build a low‐carbon and climate‐resilient industrial environment by moving away from fossil fuels and investing in clean chemical and energy generation. Faced with this challenge, gas fermentation represents a disruptive technology that will bring transformational changes to industry and society (Fig. 1). Bacterial synthesis gas (syngas) fermentation is a microbial process that contributes to goals of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E). In this microbial process, GHG such as carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO2) are fixed by a biocatalyst that simultaneously produces commodity chemicals or fuels. In 2015, the companies LanzaTech, ArcelorMittal and Primetals Technologies set up a corporation to build an industrial‐scale ethanol production facility in Ghent, Belgium (LanzaTech, 2015). The syngas fermentation technology has the potential to take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts (goal 13) by reducing GHG emissions, if applied at industrial‐scale in several facilities with considerable amounts of exhaust waste gases. The use of this autotrophic acetogenic biocatalyst enables the sustainable consumption of CO and CO2 and provides sustainable production patterns of commodity chemicals or fuels (goal 12).

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract of the gas fermentation process and links to sustainable development goals.

The syngas fermentation technology is expected to achieve a breakthrough once the industrial‐scale facility in Ghent is operating and producing 47 000 tons of ethanol per annum from waste gases originating from the steelmaking process. Within the next 10 years, this technology has the potential to build up a resilient infrastructure to capture GHG emissions from industrial waste gas streams, to promote sustainable industrialization by producing valued products and foster innovation in this field (goal 9).

Gas fermentation will also provide jobs and further career opportunities in academic and industrial bodies. Academia needs to train a cadre of researchers, able to apply their skills to the future societal challenges facing the world. Gas fermentation will also provide cutting edge technology to innovative enterprises all over the world. This might not be trivial, as competitors of LanzaTech, namely INEOS Bio and Coskata, already struggled on their route to establish an industrial‐scale biofuel production facility. However, it sets an ambitious goal which needs to be reached in order to maintain industrial and living standards on a planet with limited resources.

Gas fermentation also provides novel opportunities for renewable energy (goal 7). Currently, electricity prices face negative values, when too much wind or solar energy is fed into the grid. This surplus electricity could be used for hydrogen generation by electrolysis of water. Although generally considered to be an uneconomic process, it could help in such peak times to reduce carbon dioxide with help of hydrogen to produce industrially high‐value chemicals by acetogenic bacteria. Thus, surplus electricity from renewable resources can be used for production of platform chemicals with simultaneous reduction in GHG.

Here, we outline the background and recent developments in the field of bacterial syngas fermentation. Syngas can have multiple origins, e.g. (i) gasification of coal, petroleum, natural gas and peat coak; (ii) certain industrial waste gas streams; (iii) gasification of solid waste and (iv) pyrolysis/gasification of solid biomass. Legally, only syngas from solid biomass can be considered as ‘green carbon’. If fossil sources, or products made from fossil sources, were used to generate syngas, it has to be considered as ‘black carbon’. However, the amounts of syngas derived from fossil sources outnumber the amounts generated via pyrolysis or gasification of solid biomass (Dahmen et al., 2017). Especially, the gasification of fossil sources is a well‐established process and the world gasification industry is growing rapidly as indicated in the ‘Worldwide Syngas Database’ (http://www.gasification-syngas.org/resources/world-gasification-database/). The database provides information about plant locations, number and type of gasifiers, syngas capacity, feedstock and products. In 2015, global syngas output was 148 gigawatts thermal (GWth) and if all upcoming plans are realized, the worldwide syngas capacity will increase up to 300 GWth in 2020. The database does not consider ‘industrial waste gas’ or any other relevant energy rich waste gas output.

The used biocatalysts (also called acetogens) are anaerobic bacteria that employ the reductive acetyl‐CoA pathway to fix CO and/or CO2 and subsequently produce biofuels such as ethanol, butanol or hexanol as well as biocommodities such as acetate, lactate, butyrate, hexanoate, 2,3 butanediol and acetone using syngas as carbon and energy source. Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a synonym of acetyl‐CoA pathway, and the respective biochemistry has been elucidated in a number of recent reviews (Drake et al., 2008; Ragsdale, 2008; Schuchmann and Müller, 2014). All acetogens produce acetic acid as metabolic end‐product because the production contributes significantly to the energy conversion processes of the cells. A further important energy conversion is realized by building up a sodium ion or proton gradient over the cell membrane that is finally used to drive enzymes called ATPases that generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is the energy currency of life.

Some acetogens such as Clostridium ljungdahlii, Clostridium autoethanogenum or Clostridium carboxidivorans are of special interest, as they can produce valuable metabolic products as indicated above. Clostridium ljungdahlii and C. autoethanogenum are the best studied organisms with respect to possible applications in syngas fermentation processes. They share a special metabolic feature that enables them to convert the compulsorily produced acetate completely into the valuable product ethanol (Abubackar et al., 2016). Furthermore, both bacterial strains are closely related to each other and have the tremendous advantage that they are genetically accessible (Bengelsdorf et al., 2016). Thus, metabolic engineering of the bacterial cells is feasible and several recombinant strains have been constructed that produce biocommodities such as isopropanol, butyrate, butanol and 3‐hydroxybutyrate (Liew et al., 2016).

Clostridium carboxidivorans is of interest because it produces hexanol and hexanoic acid from syngas natively, which was shown simultaneously by two different groups (Phillips et al., 2015; Ramió‐Pujol et al., 2015). As this bacterium also produces butanol and ethanol, the term HBE (hexanol, butanol, ethanol) fermentation was introduced by Fernández‐Naveira et al. (2017). HBE fermentation is deduced from ABE (acetone, butanol, ethanol) fermentation that is known for solventogenic bacteria such Clostridium acetobutylicum and related bacteria (Bengelsdorf et al., 2017).

Acetobacterium woodii is a further acetogen of special interest, as it is used as model organism to study the metabolism of sodium‐dependent acetogenic bacteria in detail. The bacterium is also genetically accessible, and its metabolism was engineered to produce acetone (Hoffmeister et al., 2016). The available genetic tools offer several options to manipulate the metabolism of A. woodii cells and to learn more about their autotrophic lifestyle.

Moorella thermoaceticum is the acetogen that has been used to elucidate the biochemistry of the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway over decades of years. It grows under moderately thermophilic conditions (55 °C) and has also been genetically engineered to produce lactate (Kita et al., 2013; Iwasaki et al., 2017). A thermophilic acetogenic biocatalyst offers advantages for the syngas fermentation process. These include a reduced risk of contaminations, reduced costs for process cooling requirements and higher metabolic as well as diffusion rates.

Finally, a note on legislation, current regulations address the origin of carbon as the essential determinant for a product to be ‘bio’ or not. So, fuels made by microorganisms can be referred to as ‘biofuels’ only, when their substrate stems from biological material. Clearly, this does currently not apply to autotrophic acetogens when CO or CO2 are resulting from industrial processes (e.g. steel mills, chemical plants). It would, however, if CO2 is stemming from biomass gasification. And this is irrespective of the fact that in both cases microorganisms as biological catalysts are performing the conversion! This clearly will hamper companies, which are introducing the cutting edge technology of gas fermentation and are looking for financial benefits of qualifying under today's biofuels legislation, both in Europe and the USA. Thus, scientists need to emphasize that such misleading regulations should be corrected, in scientific publications as well as in information to politicians.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Microbial Biotechnology (2017) 10(5), 1167–1170

Funding Information

Work in the authors' laboratory was and is supported by grants from the BMBF project Gas‐Fermentation (FKZ 031A468A), the ERA IB 5 Program, project CO2CHEM (FKZ 031A366A), and the ERA IB 7 Program, project OBAC (FKZ 031 B0274B).

References

- Abubackar, H.N. , Bengelsdorf, F.R. , Dürre, P. , Veiga, M.C. , and Kennes, C. (2016) Improved operating strategy for continuous fermentation of carbon monoxide to fuel‐ethanol by clostridia. Appl Energy 169: 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bengelsdorf, F.R. , Poehlein, A. , Linder, S. , Erz, C. , Hummel, T. , Hoffmeister, S. , et al (2016) Industrial acetogenic biocatalysts: a comparative metabolic and genomic analysis. Front Microbiol 7: 1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengelsdorf, F.R. , Poehlein, A. , Flitsch, S.K. , Linder, S. , Schiel‐Bengelsdorf, B. , Stegmann, B.A. , et al, (2017) Host Organisms: Clostridium acetobutylicum/Clostridium beijerinckii and related organisms In Industrial Biotechnology: Microorganisms. Wittmann C., Liao J.C. (eds). Weinheim, Germany: Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. [Google Scholar]

- Dahmen, N. , Henrich, E. and Henrich, T. (2017) Synthesis gas biorefinery. In Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. Scheper, T., Belkin, S., Bley, T., Bohlmann, J., Gu, M.B., Hu, W.S. et al, (eds) p1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/10_2016_63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Drake, H.L. , Gößner, A.S. , and Daniel, S.L. (2008) Old acetogens, new light. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1125: 100–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández‐Naveira, Á. , Veiga, A.C. , and Kennes, C. (2017) H‐B‐E (Hexanol‐Butanol‐Ethanol) fermentation for the production of higher alcohols from syngas/waste gas. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 92: 712–731. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmeister, S. , Gerdom, M. , Bengelsdorf, F.R. , Linder, S. , Flüchter, S. , Öztürk, H. , et al (2016) Acetone production with metabolically engineered strains of Acetobacterium woodii . Metabol Eng 36: 37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, Y. , Kita, A. , Yoshida, K. , Tajima, T. , Yano, S. , and Shou, T. (2017) Homolactic acid fermentation by the genetically engineered thermophilic homoacetogen Moorella thermoacetica ATCC 39073. Appl Environ Microbiol 83: e00247–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita, A. , Iwasaki, Y. , Sakai, S. , Okuto, S. , Takaoka, K. , Suzuki, T. , et al (2013) Development of genetic transformation and heterologous expression system in carboxydotrophic thermophilic acetogen Moorella thermoacetica . J Biosci Bioeng 115: 347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LanzaTech . (2015) Arcelor Mittal, LanzaTech and Primetals Technologies announce partnership to construct breakthrough €87m biofuel production facility. URL http://www.lanzatech.com/arcelormittal-lanzatech-primetals-technologies-announce-partnership-construct-breakthrough-e87m-biofuel-production-facility/ [accessed May 25, 2017]

- Liew, F. , Martin, M.E. , Tappel, R.C. , Heijstra, B.D. , Mihalcea, C. , and Köpke, M. (2016) Gas fermentation‐ a flexible platform for commercial scale production of low‐carbon‐fuels and chemicals from waste and renewable feedstocks. Front Microbiol 7: 694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.R. , Atiyeh, H.K. , Tanner, R.S. , Torres, J.R. , Saxena, J. , Wilkins, M.R. , and Huhnke, R.L. (2015) Butanol and hexanol production in Clostridium carboxidivorans syngas fermentation: medium development and culture techniques. Bioresour Technol 190: 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale, S.W. (2008) Enzymology of the Wood‐Ljungdahl pathway of acetogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1125, 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramió‐Pujol, S. , Ganigué, R. , Bañeras, L. , and Colprim, J. (2015) Incubation at 25 °C prevents acid crash and enhances alcohol production in Clostridium carboxidivorans P7. Bioresour Technol 192: 296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchmann, K. , and Müller, V. (2014) Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 12: 809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]