Abstract

Background:

Renin-angiotensin (Ang)-aldosterone system not only plays a key role in the regulation of circulatory homeostasis, but also it acts as a powerful pro-inflammatory mediator. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of captopril (Cap), a known Ang-converting enzyme inhibitor, on inflammation-induced cardiac fibrosis, and heart oxidative stress status in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in male rats.

Methods:

Fifty male rats were randomly divided into five groups control, LPS (1 mg/kg/day), LPS + Cap 10 mg/kg, LPS + Cap 50 mg/kg and LPS + Cap 100 mg/kg. After 2 weeks, blood samples were taken, and hearts were harvested for evaluation of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and nitric oxide metabolite in serum and tissue hemogenate, histopathology (hematoxylin and eosin and Masson's trichrome) and oxidative stress status.

Results:

Serum IL-6 and TNF-α concentration were higher in LPS group compared to control and Cap reduced them, significantly. Heart TNF-α and IL-6 contents in LPS group were significantly higher than control (P < 0.05). The administration of Cap significantly decreased inflammatory markers level to control (P < 0.05). The higher levels of malondialdehyde and lower antioxidative markers (total thiol, superoxide dismutase, and catalase) in the heart were observed in LPS group and treatment by Cap improved them, dose-dependently. Histopathological study revealed cardiac fibrosis and more collagen content in LPS group which significantly improved by Cap treatment.

Conclusions:

Treatment by Cap reduced cardiac fibrosis possibly through improving oxidative stress status, and it can be considered to increase cardiac compliance in this condition.

Keywords: Angiotensin, cardiac, fibrosis, inflammation

Introduction

Renin-angiotensin (Ang)-aldosterone system has a key role in the regulation of circulatory homeostasis, body fluid volume, control of blood pressure and sodium balance, and also affect cardiovascular system. Studies indicated that over-activity of this system leads to cardiovascular diseases, myocardial infarction, heart failure, hypertension, and atherosclerosis.[1,2] It is also indicated that increased Ang II production and enhanced Ang-converting enzyme (ACE) activity are associated with carotid atherosclerosis.[3] Furthermore, in patients with the acute coronary syndrome, ACE activity in vascular tissue was increased.[4]

Beside the role of Ang II in the regulation of circulatory homeostasis, it acts as a powerful pro-inflammatory mediator.[5] In the course of inflammation, Ang II has several effects including increase vascular permeability through increasing prostaglandins and vascular endothelial growth factor, up-regulation of adhesion molecules and expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein and inflammatory markers.[5,6] Therefore, it seems that ACE inhibition results in a reduction of inflammation-induced cardiovascular diseases.

Inflammation plays a key role in initiation and development of many cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis.[5] Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-receptor or Toll-like receptors (TLRs) is expressed in cardiomyocytes and plays a key role in cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial dysfunction.[7] TLR-4 and TLR-2 knockout mice showed better cardiac function after induction of sepsis compare to wild-type.[7] The activation of TLRs leads to the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), which increase cytokines production and the expression of adhesion molecules.[8] These play a key role during cardiomyopathy. In the present study, we used LPS for induction of systemic inflammation. LPS is a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and is widely used for induction of inflammation.[9] It activates innate immunity and induces systemic inflammation through TLRs. TLRs are found in cells with or without immune function including endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes.[10] TLRs may initiate a pro-inflammatory response in these cells and leads to induce the release of inflammatory markers and expression of adhesion molecules.[11]

LPS-induced activation of TLRs on cardiomyocytes is thought to induce cardiac stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes[12] by stimulating angiotensinogen and hence Ang II.[13] Thus, the activation of renin-Ang-aldosterone system may lead to cardiac fibrosis.[14] In this study, we evaluated the effect of captopril (Cap), a known ACE inhibitor, on serum and heart inflammatory markers, inflammation-induced cardiac fibrosis and heart oxidative stress status in experimentally-induced inflammation in male rats.

Methods

Animals and experimental groups

Fifty male Wistar rats, 8 weeks old and weighing 200–250 g, were obtained from the Institute of Experimental Animals (Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran). They were housed in the animal house with standard temperature (20-25°C) and 12 h light/dark cycle and allowed free access to drinking water and standard rodent chow. The Local Institutional Animal Care and use Committee approved the study. The animals were randomly divided into five groups (n = 10 in each group): (1) Control, (2) LPS, (3) LPS + Cap 10 mg/kg, (4) LPS + Cap 50 mg/kg, and (5) LPS + Cap 100 mg/kg.

Lipopolysaccharide administration and pharmacological intervention

LPS-treated groups received LPS 1 mg/kg/day from Escherichia coli serotype (055:B5; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co.) for 14 days, intraperitoneally.[15] The control group received 0.9% normal saline instead of LPS. Cap (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co.) was administered 1 day before starting administration of LPS by three doses (Cap 10, 50, and 100 mg/kg/day), intraperitoneally.

At the end of the experiment, all animals were anesthetized; blood samples were taken from the heart and centrifuged. The serum samples were stored at −70°C for further analysis. The left ventricles were harvested and put in formalin 10% for later histological evaluation. The right ventricles were used for measurement of inflammatory markers and oxidative stress status in tissue homogenates.

Determination of serum and heart nitrite and inflammatory marker levels

Nitrite was measured in serum and heart hemogenate by Griess reagent method using a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Promega Corp., USA, Cat#G2930). In brief, 100 μl of serums or tissue homogenates were added to a 96-well flat-bottomed microplate. Then, sulfanilamide solution and N-1-naphtylethylenediamine dihydrochloride under acidic conditions were added to all collected samples, respectively. The absorbance was detected by a microplate reader (Biotek, USA) in 520–550 nm wavelengths. The limit detection was 2.5 μM nitrite.[16,17]

Serum and heart tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were quantified by available ELISA kits (eBioscience Co., San Diego, CA, USA) according to manufacturers’ instruction. The absorbance was measured using a microplate reader (Biotek, USA) and concentration of each factor was calculated by comparison curve established in the same measurement. Each cytokine assay was performed in duplicate each time.

Cardiac malondialdehyde

Malondialdehyde (MDA) level which is an index of lipid peroxidation was measured as previously described.[18] In brief, MDA reacts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and produces a red colored complex. First, the TBA-trichloroacetic acid-HCL reagent was added to tissue homogenate. Then, the solution was heated in a water bath for 40 min. Next, it was centrifuged and the absorbance measured at 535 nm. The MDA concentration was calculated as follows: C (m) = Absorbance/(1.65 × 105).

Cardiac total thiol concentration

Cardiac total thiol groups were measured using 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) as the reagent. In brief, 1 ml of Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) buffer (pH = 8.6) was added to 50 μl heart homogenate. Then, the absorbance was read at 412 nm against Tris-EDTA buffer alone (A1). Next, 20 μl DTNB reagents were added to the mixture and the sample absorbance was read again (A2). The absorbance of DTNB reagent was read as a blank (B). Total thiol concentration (mM) was measured as previously described using the following equation:

Total thiol concentration (mM) = (A2−A1−B) × 1.07/0.05 × 13.6

Cardiac superoxide dismutase and catalase

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) was measured according to a method of Madesh and Balasubramanian.[19] One unit of SOD was defined as the amount of enzyme required to inhibit the rate of 3-(4,5-dimethythiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide reduction by 50%. The results were shown as unit per milligram protein. Catalase activity was measured as previously described.[20] One unit of catalase activity is determined as the micromoles of the hydrogen peroxide consumed per milligram of protein sample.

Histological examination

The left ventricles were embedded in formalin 10% and sliced at 10 μm, deparaffinized, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) and examined under light microscopy. An average number of 10 randomly selected fields in each slide in six animals per group were analyzed by investigators who were unaware of the animal groups.

For evaluation of cardiac fibrosis, the sections were stained with Masson's trichrome. A blue stain indicated positive staining for collagen. The fibrotic changes were assessed by pathologist in 10 randomly selected high-power fields (×400) for each tissue slide and reported as collagen content. The fractional area of fibrosis was quantified using NIH image software (Image J).[21]

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error. The analysis was performed using the SPSS software version 20 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The comparisons were evaluated using one-way ANOVA, followed by LSD post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Serum and tissue inflammatory markers

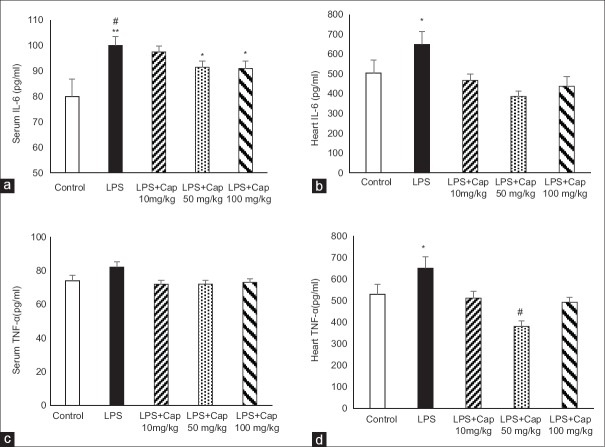

As we expected, serum IL-6 in LPS group was significantly higher than that of control group (P < 0.01). Administration of Cap by all doses (10, 50, and 100 mg/kg) decreased serum levels of IL-6 compared to LPS group which was statistically significant at higher doses (Cap 50 and 100 mg/kg) (P < 0.05) [Figure 1a]. There were no significant differences in serum IL-6 between LPS + Cap 50 and 100 mg/kg and control group (P > 0.05). Heart IL-6 levels in LPS group were higher than control and Cap reduced it significantly [Figure 1b]. Treatment by Cap 50 mg/kg lowered heart IL-6 content to lower than control level (P < 0.05) [Figure 1b].

Figure 1.

Serum interleukin-6 levels in experimental groups (a and c). #P < 0.05 compared to control; *P < 0.05 compared to control and lipopolysaccharide; **P < 0.01 compared to control. (b and d) Heart tumor necrosis factor alpha levels. #P < 0.001 compare to lipopolysaccharide; *P < 0.05 compared to other groups. n = 6 each group

Although LPS group had higher serum TNF-α level compared to control, it was not statistically significant. Treatment by Cap did not change serum TNF-α [Figure 1c]. However, the evaluation of heart TNF-α levels showed that TNF-α content in LPS group was significantly higher than control rats (P < 0.05). Administration of Cap significantly reversed heart TNF-α content to control level (LPS + Cap 10 and 100 mg/kg; P < 0.05) and even lower than control levels (LPS + Cap 50 mg/kg; P < 0.01) [Figure 1d].

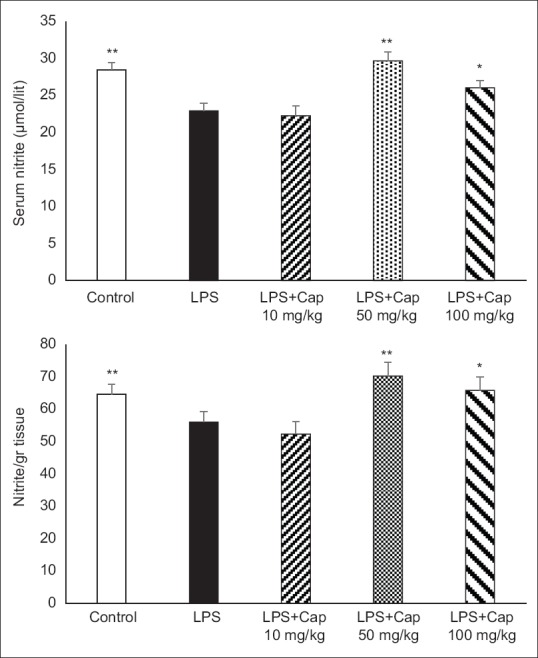

Serum and heart nitric oxide metabolite

A significant reduction in serum and heart nitrite levels were observed in LPS group compared to control group (P < 0.01) [Figure 2]. Cap by dose of 10 mg/kg did not alter serum and heart nitrite levels, however, administration of 50 and 100 mg/kg Cap increased nitric oxide (NO) metabolite levels in serum and heart (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05 compared to LPS and LPS + Cap 10 mg/kg, respectively).

Figure 2.

Serum and heart nitrite concentrations in experimental groups. *P < 0.05 compared lipopolysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide + captopril 10 mg/kg; **P < 0.01 compared to lipopolysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide + captopril 10 mg/kg. n = 6 each group

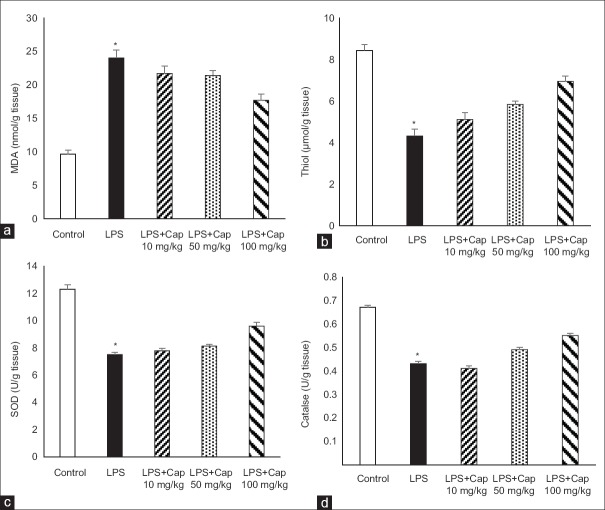

Cardiac malondialdehyde and total thiol concentration

The animals of LPS group had higher MDA concentration [Figure 3a] and lower thiol contents [Figure 3b] in heart tissues compared to control animals (both P < 0.001). Administration of Cap in LPS-treated group by lowest dose (10 mg/kg) slightly decreased MDA and increased thiol concentration which were not statistically significant, however, in the animals who treated by higher doses of Cap, these changes were significant compared to LPS group (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Heart malondialdehyde (a), total thiol (b), superoxide dismutase (c) and catalase (d) in the heart tissue. *P < 0.05 compared to control and lipopolysaccharide + captopril 100 mg/kg; n = 6 in each group

Cardiac superoxide dismutase and catalase activity

LPS administration decreased heart SOD compared to control animals (P < 0.001) which was significantly increased by 100 mg/kg Cap administration (P < 0.01). Administration of 10 and 50 mg/kg Cap could not improve heart SOD compared to LPS group [Figure 3c].

The evaluation of tissue catalase indicated that catalase in the heart tissue was reduced after LPS administration (P < 0.001). Treatment by 100 mg/kg Cap in LPS groups increased it in the heart tissue, significantly (P < 0.05 compare to LPS group), however, Cap by dose of 10 and 50 mg/kg did not alter tissue catalase [Figure 3d].

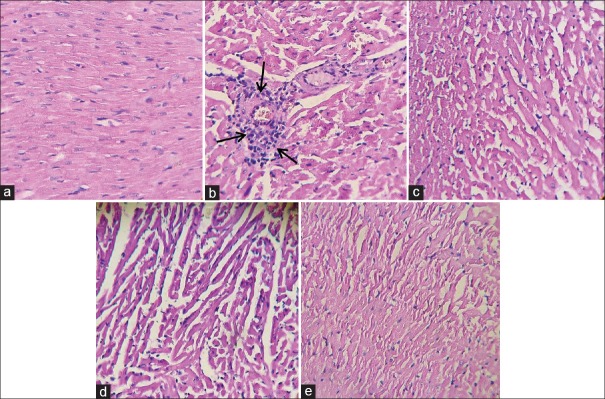

Histopathological findings

As illustrated in Figure 4a and b, the cardiac muscle fibers in control group revealed no pathological changes in H and E stained sections. LPS group showed focal inflammatory cell infiltration and disarrangement of muscle fibers and administration of Cap reduced the severity of the pathological changes [Figure 4c-e].

Figure 4.

The light micrograph of heart tissue stained by hematoxylin and eosin. (a) Control group with normal architecture (×20, hematoxylin and eosin). (b) lipopolysaccharide group showing infiltration of inflammatory cells (arrows) and disarrangement of fibers. Captopril reduced inflammation in the myocardium (c-e)

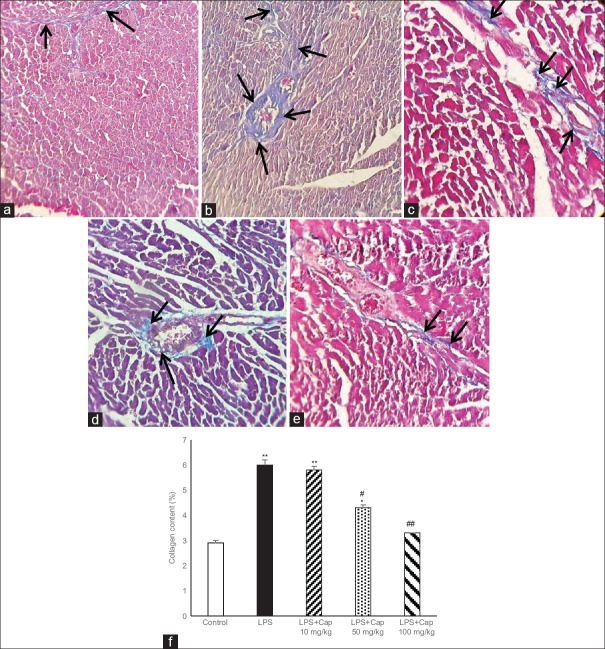

To investigate whether the LPS-induced cardiac fibrosis, the amount of collagen content was detected. Based on the trichrome staining, LPS administration significantly increased the intensity of myocardial fibrosis in myocardium and around the vessels (in blue color) [Figure 5a and b]. In addition, the interstitial collagen deposition in LPS group was higher than control. Figure 5c-e illustrates that Cap induced a dose-dependent decrease in cardiac fibrosis and percent of collagen content in LPS groups [Figure 5f].

Figure 5.

Masson trichrome staining of left ventricular muscles of control (a) and lipopolysaccharide (b) groups show more collagen deposition in lipopolysaccharide-treated group. Blue color illustrates collagen fibers. Black arrows indicate collagen fibers. (c-e) Captopril reduced cardiac fibrosis. Left ventricular wall fibrosis shows higher collagen content (%) in lipopolysaccharide group compare to control which reduced dose-dependently by captopril (f). *P < 0.05 compared to control; **P < 0.01 compare to control. #P < 0.05 compared to lipopolysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide + captopril 10 mg/kg; ##P < 0.05 compared to lipopolysaccharide and lipopolysaccharide + captopril 10 mg/kg

Discussion

In the present study, we used LPS for induction of inflammation in the animals which is a known model for induction of inflammation.[9] Our results showed higher inflammatory markers, fibrosis, and more collagen content in the heart in LPS group. LPS binds to specific cell membrane receptors of different cells including endothelial cells and leukocytes and release different inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, ILs, NO and oxygen free radicals. All of these mediators are involved in the pathophysiology of endotoxin-induced acute injury.[8,22] In the present study, we found higher inflammatory cytokine levels in LPS group compare to control, although, there was no statistically significant in serum TNF-α compare to control. Previous studies indicated that level of TNF-α tend to be greater in septic animals than control, however, it was not statistically significant.[23] In addition, increased MDA level, which an index of lipid peroxidation and reduced tissue levels of total thiol, SOD, and catalase in LPS group indicates higher reactive oxygen species (ROS) which support the previous studies. We also reported that LPS group had lower serum and heart NO metabolite. NO has a complex role in inflammation-induced cardiac dysfunction.[24] It produced by all types of cardiac cells and has different cardiovascular effects in normal and pathological conditions. NO is generated during conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline by three isoforms of NO synthase. It is indicated that inducible form of NO synthase is overproduced in sepsis which is important in late stage of sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction.[24]

Our results showed that cardiac fibrosis induced in LPS group which supported the previous studies.[21,27] Lew et al. indicated that exposure to subclinical levels of LPS induces cardiac fibrosis even after 2 weeks. They suggested that this may relate to a decrease in cardiac miR-29c and an increase in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 expression.[25]

Ang II which is a potent vasoconstrictor is now recognized as a multifunctional hormone important in the regulation of vascular function, including cell growth, migration, inflammation, and fibrosis. Our results showed that treatment by Cap, a known ACE inhibitor, improved cardiac fibrosis and lowered collagen content in heart tissue. To investigate the mechanism of Cap on cardiac fibrosis, we measured serum and heart levels of inflammatory markers including IL-6 and TNF-α. Administration of Cap significantly reduced serum and tissue levels of those cytokines. Ang II has several effects during inflammation. It increases vascular permeability, contributes to recruitment of inflammatory cells, and regulates some transcriptional factors such as NF-κB.[1,6,26]

One of the intracellular signaling pathways involved in Ang II-induced inflammation is the production of ROS.[6] ROS appears to be important in Ang II signaling in vascular cells.[27] It is demonstrated that exogenous oxidants activate the same signaling cascades as Ang II. On the other hand, major targets of ROS include transcription factors, tyrosine kinases and mitogen-activated protein kinases, all of which are regulated by Ang II.[28] In this study, we found that Cap improved tissue antioxidative markers, dose-dependently. Although the effect of Ang II on ROS production is becoming clearer, there is still a paucity of knowledge to its mechanism and how these redox-sensitive processes lead to vascular inflammation and fibrosis and what factors act as damaging stress signals to induce vascular injury. In the present study, we did not measure blood pressure in animals who received Cap, and this is the limitation of the study.

The clinical significance of this study is that in conditions with exposure to subclinical LPS such as obesity or high-fat diet, diabetes, smoking, cardiac fibrosis occurs which can contribute to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.[29] Treatment by Cap improves cardiac fibrosis and therefore, increases cardiac compliance in these conditions.

Financial support and sponsorship

The authors acknowledge the Vice Chancellor of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for their financial support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Vice Chancellor of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences for their financial support.

References

- 1.Mentz RJ, Bakris GL, Waeber B, McMurray JJ, Gheorghiade M, Ruilope LM, et al. The past, present and future of renin-angiotensin aldosterone system inhibition. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1677–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrario CM, Strawn WB. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and proinflammatory mediators in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuhara M, Geary RL, Diz DI, Gallagher PE, Wilson JA, Glazier SS, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme expression in human carotid artery atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2000;35(1 Pt 2):353–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoshida S, Kato J, Nishino M, Egami Y, Takeda T, Kawabata M, et al. Increased angiotensin-converting enzyme activity in coronary artery specimens from patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2001;103:630–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pacurari M, Kafoury R, Tchounwou PB, Ndebele K. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in vascular inflammation and remodeling. Int J Inflam 2014. 2014:689360. doi: 10.1155/2014/689360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchesi C, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in vascular inflammation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:367–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balija TM, Lowry SF. Lipopolysaccharide and sepsis-associated myocardial dysfunction. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:248–53. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834536ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn J, Kim J. Mechanisms and consequences of inflammatory signaling in the myocardium. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:510–6. doi: 10.1007/s11906-012-0309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, Star RA. Animal models of sepsis and sepsis-induced kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2868–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI39421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asgharzadeh F, Rouzbahani R, Khazaei M. Chronic low-grade inflammation: Etiology and its effects. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2016;34:408–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chagnon F, Metz CN, Bucala R, Lesur O. Endotoxin-induced myocardial dysfunction: Effects of macrophage migration inhibitory factor neutralization. Circ Res. 2005;96:1095–102. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000168327.22888.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuda S, Lew WY. Lipopolysaccharide depresses cardiac contractility and beta-adrenergic contractile response by decreasing myofilament response to Ca2+ in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1997;81:1011–20. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.6.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki J, Bayna E, Li HL, Molle ED, Lew WY. Lipopolysaccharide activates calcineurin in ventricular myocytes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:491–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: Physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norouzi F, Abareshi A, Asgharzadeh F, Beheshti F, Hosseini M, Farzadnia M, et al. The effect of Nigella sativa on inflammation-induced myocardial fibrosis in male rats. Res Pharm Sci. 2017;12:74–81. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.199050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nematollahi S, Nematbakhsh M, Haghjooyjavanmard S, Khazaei M, Salehi M. Inducible nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in ischemic hindlimb of rat. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2009;153:125–9. doi: 10.5507/bp.2009.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khazaei M, Nematbakhsh M. The effect of hypertension on serum nitric oxide and vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations. A study in DOCA-Salt hypertensive ovariectomized rats. Regul Pept. 2006;135:91–4. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehri S, Abnous K, Khooei A, Mousavi SH, Shariaty VM, Hosseinzadeh H. Crocin reduced acrylamide-induced neurotoxicity in Wistar rat through inhibition of oxidative stress. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2015;18:902–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madesh M, Balasubramanian KA. Microtiter plate assay for superoxide dismutase using MTT reduction by superoxide. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1998;35:184–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–6. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lew WY, Bayna E, Molle ED, Dalton ND, Lai NC, Bhargava V, et al. Recurrent exposure to subclinical lipopolysaccharide increases mortality and induces cardiac fibrosis in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hohensinner PJ, Niessner A, Huber K, Weyand CM, Wojta J. Inflammation and cardiac outcome. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24:259–64. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328344f50f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDonough KH, Virag JI. Sepsis-induced myocardial dysfunction and myocardial protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury. Front Biosci. 2006;11:23–32. doi: 10.2741/1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanotti-Cavazzoni SL, Hollenberg SM. Cardiac dysfunction in severe sepsis and septic shock. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:392–7. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283307a4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lew WY, Bayna E, Dalle Molle E, Contu R, Condorelli G, Tang T. Myocardial fibrosis induced by exposure to subclinical lipopolysaccharide is associated with decreased miR-29c and enhanced NOX2 expression in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki Y, Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Egido J. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:881–900. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elmi S, Sallam NA, Rahman MM, Teng X, Hunter AL, Moien-Afshari F, et al. Sulfaphenazole treatment restores endothelium-dependent vasodilation in diabetic mice. Vascul Pharmacol. 2008;48:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species and angiotensin II signaling in vascular cells – Implications in cardiovascular disease. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:1263–73. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westermann D, Kasner M, Steendijk P, Spillmann F, Riad A, Weitmann K, et al. Role of left ventricular stiffness in heart failure with normal ejection fraction. Circulation. 2008;117:2051–60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]