Abstract

Background:

Multiligamentous injuries of knee remain a gray area as far as guidelines for management are concerned due to absence of large-scale, prospective controlled trials. This article reviews the recent evidence-based literature and trends in treatment of multiligamentous injuries and establishes the needful protocol, keeping in view the current concepts.

Materials and Methods:

Two reviewers individually assessed the available data indexed on PubMed and Medline and compiled data on incidence, surgical versus nonsurgical treatment, timing of surgery, and repair versus reconstruction of multiligamentous injury.

Results:

Evolving trends do not clearly describe treatment, but most studies have shown increasing inclination toward an early, staged/single surgical procedure for multiligamentous injuries involving cruciate and collateral ligaments. Medial complex injuries have shown better results with conservative treatment with surgical reconstruction of concomitant injuries.

Conclusion:

Multiligamentous injury still remains a gray area due to unavailability of a formal guideline to treatment in the absence of large-scale, blinded prospective controlled trials. Any in multiligamentous injuries any intervention needs to be individualized by the presence of any life- or limb-threatening complication. The risks and guarded prognosis with both surgical and non-surgical modalities of treatment should be explained to patient and relations.

Keywords: Arthroscopy, bi-cruciate injury, knee dislocation, multiligamentous injury, systematic review

MeSH terms: Orthopedics, arthroscopy, multiligament injury, knee dislocation, knee injury

Introduction

Multiligamentous injuries have been an uncommonly reported orthopedic diagnosis. It has been defined as a complete cruciate tear (Grade III) with a partial/complete tear of medial/lateral collateral (Grade II/III) or a partial or complete tear of the other cruciate ligament (Grade II or III).1 A major hindrance to establish a uniform treatment guideline is existence of various life- and limb-threatening complications (neurovascular compromise) occurring with dislocation of the knee, which perhaps remains the most common cause of multiligamentous injuries.2

Since the incidence of knee dislocation accounts for <0.02% of orthopedic injuries,2,3,4 large-scale data for comparative analysis and defining a standard treatment protocol are not available. There is a paucity of high level of evidence for the optimal management and results of treatment being offered.

The associated morbidity and the poor clinical and rehabilitation outcomes have attracted attention to the rare but serious challenge. Various controversies regarding operative versus nonoperative treatment, repair versus reconstruction, time of operative intervention, and clinical outcomes of surgical versus nonsurgical therapy remain unanswered.

Due to inadequacy of data included in each study, we chose to compile an evidence-based systematic review to compare the outcomes of various studies over the past 15 years and define a protocol of treatment of multiligamentous knee injuries.

Materials and Methods

Two independent reviewers compiled data over 15 years from PubMed and Medline indexed journals using keywords of search as: multi-ligamentous injury knee, knee dislocation–multi ligament injury, and bi-cruciate ligament injury knee. The inclusion criteria were: Level 1–4 evidence, multiligamentous injury – 2 or more of 4 ligaments involved, functional outcomes defined, minimum followup of 12 months, and presence of a control group.

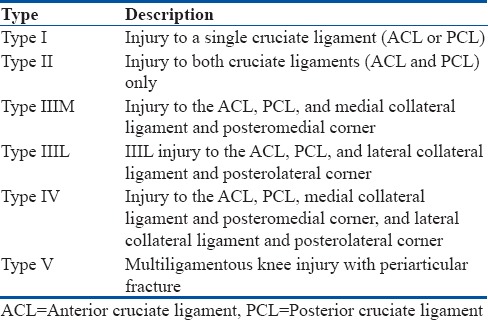

Functional outcomes were scrutinized using Lysholm score, Tegner scale, International Knee Documentation Committee (IDKC) score, and return to employment/sports. Although the above stated measures of functional outcomes have not yet been validated for multiligamentous injuries specifically, various studies have standardized them to measure outcomes. Each reference list from the screened articles was manually checked to verify that relevant articles were not missed. The studies not complying with the above referencing were excluded. Type of treatment (surgical/nonsurgical), timing of surgery (<3 weeks/>3 weeks), and results of repair versus reconstruction were recorded from the studies. We made use of Schenck Classification of Knee Dislocations for standardization of ligament injuries5 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Schenck classification of knee dislocations

Results

The total indexed articles on PubMed and Medline were 521 of which relevant articles matching our criteria were 38. The required data were compared and analyzed.

The most common ligamentous injury accompanying anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) was the posterolateral complex (PLC) followed by medial collateral ligament (MCL)6,7,8 [Table 2].

Table 2.

Recent studies depicting injury patterns

Surgical versus conservative treatment

From old to recent literature,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 it has been concluded that there has been a shift of management from nonoperative to acute or delayed, single or staged operative treatment with significantly higher mean postoperative Lysholm score, Tegner scale, and IDKC scores on long term followup. MCL was most commonly managed conservatively following a cruciate ligament reconstruction and long term followup showed good-to-excellent results.16 Surgical treatment in cases of multiligamentous injury remains the key to cruciate and lateral collateral ligament.17

Repair versus reconstruction treatment

McCarthy et al.18 and Dong et al.19 documented a role of primary/delayed repair only in avulsion injuries of cruciate ligaments and have advocated on conclusive evidence of reconstruction having better results in midsubstance tears involving collateral and cruciate ligaments.

However, reports show a high failure rate of PLC re-injury and failures after repairs. Tenodesis has shown better results as compared to primary repair.11 Most studies stressed on early reconstruction of multiligamentous injuries where authors preferred ACL in combination with PLC reconstruction with or without posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) reconstruction.20

Early versus delayed treatment

Early surgery (<3 week) has shown higher incidences of postoperative stiffness and a fixed flexion deformity with higher rates of manipulation under general anesthesia as compared to delayed repair.5,20,21,22

Whereas delayed repair has higher chances of scarring of soft tissue with more difficulty in identification and navigation in the joint leading to higher chances of vascular complications.23 No conclusive evidence is suggestive of an advantage offered by a single or a staged procedure.

Discussion

Treatment and rehabilitation of multiligamentous injury is a difficult orthopedic challenge. Due to low incidence of cases, associated limb- and life threatening injuries, biased opinion regarding treatment, and nonavailability of double-blinded prospective randomized controlled trials, definitive protocols of treatment have not been established. Most studies have not been randomized or prospective whereby the results are biased due to variability of administered treatment due to associated injuries.

Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment

Nonoperative modality of treatment has been documented in the past. With the advent of newer methods of staged arthroscopic reconstructions, the nonoperative modality has only been reserved for old sedentary patients or cases involving polytrauma patients requiring salvaging surgeries first.9,10,24,25

A subgroup analysis of 23 multiligament-injured knees by Werier et al.9 showed that the mean Lysholm score in the reconstructed group was 80 compared with 56 in the nonoperative group. Bonanzinga et al.12 concluded that combined ACL and PLC reconstruction seems to be the most effective approach to the multiligamentous lesions since biomechanical studies have proved the action of posterolateral corner as a secondary restrain post ACL injury and so, single-stage repair becomes essential to prevent the risk of reinjury.13

A recent study by Dhillon et al.14 also concluded that nonoperative management of a concomitant Type B PLC injury adversely affects the outcomes of ACL reconstruction in these patients. Type A PLC injuries, on the other hand, do well without surgery and can be left as such even when associated with a concomitant ACL tear.

With regard to combined ACL and MCL injuries, it has been clearly documented even on long term followup that concomitant MCL injuries can be treated conservatively and that valgus laxity does not affect AP laxity even at a followup of 36 months.16

On the contrary, Laprade and Wijdicks26 threw light on a method of more anatomical medial collateral reconstruction over sling procedures due to improved outcomes with more objective measurement technique. There has been increasing evidence of internal bracing also in injuries to MCL and posteromedial corner.27

Similarly, better results of an anatomic posterolateral corner reconstruction have also inclined surgeons toward surgical modality than conservative treatment in PLC injuries.28,29 The above-mentioned studies using newer techniques show increasing inclination toward better results and surgical treatment.

Type-IIIM knee dislocations more frequently had complete deep MCL tears and tears of the posterior oblique ligament compared to Type IV knee dislocations. The study also concluded that injury to at least one structure in the posteromedial corner occurred in 81% of patients, regardless of injury pattern, and operative treatment had better results compared to nonoperative treatment in Grade III injuries to MCL in various combined injury patterns. The overall reoperation rate was 28%, and the most common indication for reoperation was stiffness.30,31

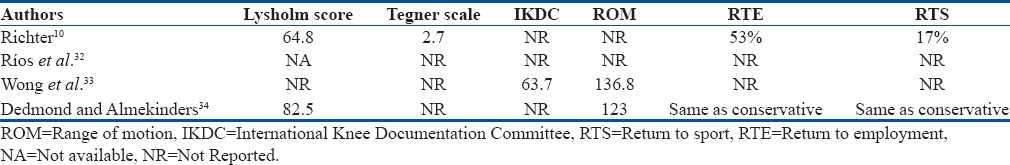

Patient satisfaction scores as compared in four studies involving multiligamentous injury show higher mean Lysholm score and mean Tegner scale score in patients treated surgically as compared to nonoperative treatment even up to 4 years of followup. There have been studies which have documented a higher mean IDKC score in patients treated surgically in comparison to conservatively treated group.10,32,33

Dedmond and Almekinders analyzed 15 case series comparing surgical versus conservative treatment which revealed statistically significant scores (Lysholm score of 85.2 vs. 66.5), range of motion (ROM) (123° vs. 108°), and a decreased flexion contracture (0.5° vs. 3.5°) in patients treated surgically. However, there was no statistically significant difference with regard to presence of instability, return to work, or return to preinjury activity level.34

The primary injured cruciate is identified along with secondary collateral and cruciate injuries by clinical and radiological examination. As far as the sequence of repair is concerned, it depends on individual case. In cases where Grade II injuries to collaterals are suspected, repair/reconstruction is usually not recommended. In cases where clinical and radiological evidence confirms bi-cruciate injury, PCL reconstruction with acute or delayed (>4 weeks) ACL reconstruction is advised. Van der Wal et al.29 advocated correction of primary rotatory instability in the form of PLC followed by concomitant or staged PCL and then ACL reconstruction in cases where PLC, PCL, and ACL injuries are concomitant.29,35,36

Another school of thought by Strobel et al. states that PCL should be repaired first to reduce the posterior sag followed by PLC repair and then ACL reconstruction in single or staged manner as per surgeon's preference.37

Delayed versus acute repair

No general consensus exists regarding the best-suited time frame for surgery.38 The timing of surgery for multiligamentous injury is still controversial with most surgeons advocating the role of early (<3 weeks) single-stage surgery and rehabilitation with few others who have documented better results with staged procedure.38,39,40,41

Both old and new literature by Jari and Shelbourne42 and Tay and MacDonald,43 respectively, suggest decreased risk of arthrofibrosis in a staged procedure but simultaneously increased higher risk of failure of PLC reconstruction in the absence of a functioning ACL. Literature by Jiang et al.44 supports this approach, as staged management had the highest percentage of excellent or good outcomes in Type-IIIM and Type-IIIL knees in a recent systematic review.

Early surgery has documented the advantage of easier identification of anatomical landmarks and less scarring, making repair easier with lesser risk of vascular complications.4

Mook et al. have also described that patients taken for delayed repair have better ROM and lesser need for collateral repair with moderate-to-good results of delayed surgery.11

However, Cook et al.22 concluded that knee stiffness requiring manipulation under anesthesia and/or lysis of adhesion was significantly higher in patients treated within 3 weeks of injury.

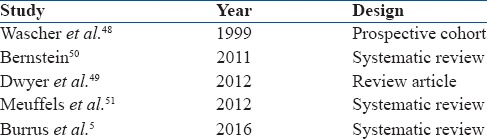

Karataglis et al. did a series of studies where 16 patients (46%) with chronic multiligamentous deficiency were able to participate in sports after surgery and 32 (91%) returned to work.45 Fanelli and Edson treated 41 patients who sustained chronic PCL/PLC and showed excellent results at a mean followup of 2 years.46 In comparison to this, Shelbourne et al. performed a comparative study between the results of delayed versus acute repair in multiligamentous injuries and concluded even poor functional scores in patients who received delayed treatment.47 Delayed repair has also shown good functional outcomes in comparison to functional scores of early repair/reconstruction, and a definite answer remains unclear48,49,50,51 [Table 3].

Table 3.

Studies comparing early versus delayed reconstruction

Repair versus reconstruction

Authors also have different views comparing repair to reconstruction in cases of multiligamentous injuries. A particularly increased risk of failure has been documented in cases of repair of PLC and fibular collateral ligament in comparison to reconstruction using biceps tenodesis.12,19 Although most authors today practice ACL reconstruction to repair in cases of multiligamentous injuries, avulsion injuries of ACL are most amenable to repair. Midsubstance tears, acute and chronic, have shown good results only with reconstruction.1

Stannard et al. conducted a prospective trial directly comparing repair versus reconstruction of PLC in 57 knees. Nearly 77% had multiligamentous injury and the repair failure rate was 37%, compared with a reconstruction failure rate of 9%. The difference in stability on clinical examination between repairs and reconstructions was statistically significant (P < 0.05)52 whereas Mariani et al. have shown no difference in functional outcomes where 9 of 23 patients included in the study showed only fair-to-poor outcomes (qualification C and D).53

Primary repair of ACL/PCL injuries has also shown good to excellent Lysholm scores, comparable to reconstruction, in two independent studies with a mean followup of 24 and 48 months, respectively.46,54

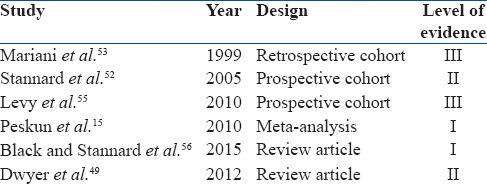

As far as repair versus reconstruction is concerned, author wishes to reinforce lesser chances of failure of primary reconstruction of PLC structures in comparison to repair and use of fixation/repair techniques, especially in cases of cruciate injuries associated with avulsion fractures.49,55,56 Chronic midsubstance repairs have proven poorer outcomes in comparison to reconstruction. Lateral ligament complex repair has also shown to have good functional outcomes with quite low revision rates [Table 4].

Table 4.

Studies comparing repair with reconstruction as treatment

The current literature has shown contrasting results with similar injuries using different treatment methodologies. The exact management protocol of these injuries still remains unanswered. The associated injuries with knee dislocation include administration of treatment for salvage of life/limb on priority. Author prefers an acute (<3 weeks) surgical approach with reconstruction of most cruciate injuries associated with PLC injuries. Whereas MCL complex has shown good results with both surgical and nonoperative management following definitive surgery where Grade II and III injuries typically from its femoral attachment have better prognosis as compared to injury at the tibial attachment.42,57,58,59

Method of fixation

Authors have used aperture and suspensory fixation techniques for fixation of graft. There have been individual preferences with no clear cut superiority of one over the other method. Literature is scarce in terms of methods of fixation in multiligamentous injuries.

Suspensory fixation using a fixed or adjustable loop has provided superiority over cross pins and aperture fixation with respect to lesser graft cutouts per operatively and more anatomical restoration of footprint but at cost of more tunnel dilations and bungee effect postoperatively. Whereas, aperture fixation has increased reports of graft cutouts but offers superior stability and improved stiffness of fixation by mitigation of bungee cord effect and windshield wiper effect. Most authors have settled on the concept of a hybrid fixation for fixation of grafts even in cases of multiligamentous injuries.59,60,61,62,63,64,65

Choice of grafts

Most authors have varying opinions and preferences for choice of graft used. There have been a wide variety of grafts available which include autografts (hamstrings, quadriceps, peroneus, and bone-patellar-tendon-bone [BPTB]) and allografts. Autografts remain the most commonly used from same or contralateral limb in cases of multiligamentous injuries. There are no specific indications for choice of graft to be used, and preference varies as per the properties of graft. Hamstrings graft is easy to harvest with lower donor site morbidity as compared to BPTB which has a more firm and lesser elastic property. There is no literature confirming clear superiority of one over the other, especially in cases of multiligamentous injuries or clearly stating choice of graft for reconstruction of any specific ligament.66,67,68,69,70,71

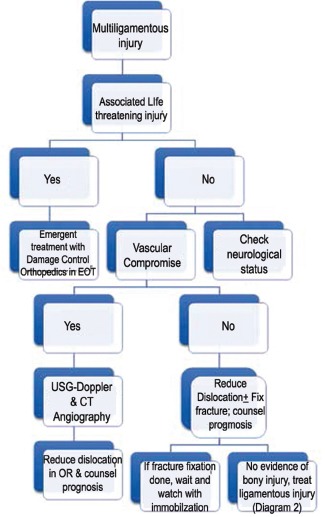

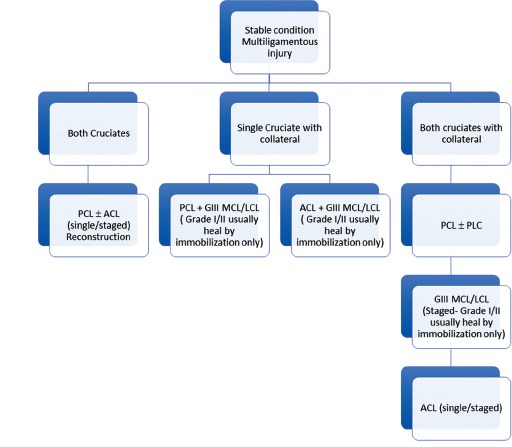

Our review suggests that, with evolving minimally invasive techniques and early and better diagnostic modalities, surgical treatment, single/staged, has better functional outcomes in comparison to conservative management. Although in cases with life-/limb-threatening injuries, salvage surgery remains of prime importance followed by ligament reconstruction in same or different setting [Flowcharts 1 and 2] and various studies as briefly shown in Tables 3-5.

Flowchart 1.

Protocol of management of multiligamentous injury of knee

Flowchart 2.

Protocol for stable multiligamentous injury

Table 5.

Outcome of operative versus nonoperative treatment

Conclusion

Multiligamentous injury still remains a gray area due to nonavailability of a formal guideline to treatment in the absence of large–scale, blinded prospective controlled trials. Any intervention needs to be individualized by the presence of any life- or limb-threatening complication only after explaining risks and guarded prognosis with both surgical and nonsurgical modalities of treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cox C, Spindler K. Multi-ligamentous knee injuries – Surgical treatment Algorithm. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2008;3:198–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rihn JA, Groff YJ, Harner CD, Cha PS. The acutely dislocated knee: Evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:334–46. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoover NW. Injuries of the popliteal artery associated with fractures and dislocations. Surg Clin North Am. 1961;41:1099–112. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)36451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RE, Smith EC, Bone GE. Vascular and orthopedic complications of knee dislocation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;149:554–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrus MT, Werner BC, Griffin JW, Gwathmey FW, Miller MD. Diagnostic and management strategies for multiligament knee injuries: A critical analysis review. JBJS Rev. 2016;4:1–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.O.00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker EH, Watson JD, Dreese JC. Investigation of multiligamentous knee injury patterns with associated injuries presenting at a level I trauma center. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27:226–31. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318270def4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Hao Y, Zhang YM, Wang M, Zhou Y, et al. Surgical management of the multiple-ligament injured knee: A case series from Chongqing, China and review of published reports. Orthop Surg. 2013;5:239–49. doi: 10.1111/os.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson MJ, Browning WM, 3rd, Urband CE, Kluczynski MA, Bisson LJ. A systematic summary of systematic reviews on the topic of the anterior cruciate ligament. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4:2325967116634074. doi: 10.1177/2325967116634074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werier J, Keating JF, Meek RN. Complete dislocation of the knee – The long term results of ligamentous reconstruction. Knee. 1998;5:255–60. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter M, Bosch U, Wippermann B, Hofmann A, Krettek C. Comparison of surgical repair or reconstruction of the cruciate ligaments versus nonsurgical treatment in patients with traumatic knee dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:718–27. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300051601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mook WR, Miller MD, Diduch DR, Hertel J, Boachie-Adjei Y, Hart JM, et al. Multiple-ligament knee injuries: A systematic review of the timing of operative intervention and postoperative rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2946–57. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonanzinga T, Zaffagnini S, Grassi A, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Neri MP, Marcacci M. Management of combined anterior cruciate ligament-posterolateral corner tears: A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1496–503. doi: 10.1177/0363546513507555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SJ, Choi DH, Hwang BY. The influence of posterolateral rotatory instability on ACL reconstruction: Comparison between isolated ACL reconstruction and ACL reconstruction combined with posterolateral corner reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:253–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhillon M, Akkina N, Prabhakar S, Bali K. Evaluation of outcomes in conservatively managed concomitant type A and B posterolateral corner injuries in ACL deficient patients undergoing ACL reconstruction. Knee. 2012;19:769–72. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peskun CJ, Levy BA, Fanelli GC, Stannard JP, Stuart MJ, MacDonald PB, et al. Diagnosis and management of knee dislocations. Phys Sportsmed. 2010;38:101–11. doi: 10.3810/psm.2010.12.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaffagnini S, Bonanzinga T, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Giordano G, Bruni D, Bignozzi S, et al. Does chronic medial collateral ligament laxity influence the outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? A prospective evaluation with a minimum three-year followup. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:1060–4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.26183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Indelicato PA. Isolated medial collateral injuries in the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:9–14. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCarthy M, Ridley TJ, Bollier M, Cook S, Wolf B, Amendola A. Posterolateral Knee Reconstruction Versus Repair. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:20–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong J, Wang XF, Men X, Zhu J, Walker GN, Zheng XZ, et al. Surgical treatment of acute grade III medial collateral ligament injury combined with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Anatomic ligament repair versus triangular ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:1108–16. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levy BA, Dajani KA, Morgan JA, Shah JP, Dahm DL, Stuart MJ, et al. Repair versus reconstruction of the fibular collateral ligament and posterolateral corner in the multiligament-injured knee. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:804–9. doi: 10.1177/0363546509352459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krutsch W, Zellner J, Baumann F, Pfeifer C, Nerlich M, Angele P, et al. Timing of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction within the first year after trauma and its influence on treatment of cartilage and meniscus pathology. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:418–25. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook S, Ridley TJ, McCarthy MA, Gao Y, Wolf BR, Amendola A, et al. Surgical treatment of multiligament knee injuries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:2983–91. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3451-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy BA, Fanelli GC, Whelan DB, Stannard JP, MacDonald PA, Boyd JL, et al. Controversies in the treatment of knee dislocations and multiligament reconstruction. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:197–206. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200904000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almekinders LC, Logan TC. Results following treatment of traumatic dislocations of the knee joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;284:203–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kannus P, Järvinen M. Nonoperative treatment of acute knee ligament injuries. A review with special reference to indications and methods. Sports Med. 1990;9:244–60. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199009040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laprade RF, Wijdicks CA. Surgical technique: Development of an anatomic medial knee reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:806–14. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2061-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lubowitz JH, MacKay G, Gilmer B. Knee medial collateral ligament and posteromedial corner anatomic repair with internal bracing. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3:e505–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djian P. Posterolateral knee reconstruction. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2015;101:S159–70. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Wal WA, Heesterbeek PJ, van Tienen TG, Busch VJ, van Ochten JH, Wymenga AB, et al. Anatomical reconstruction of posterolateral corner and combined injuries of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:221–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner BC, Hadeed MM, Gwathmey FW, Jr, Gaskin CM, Hart JM, Miller MD, et al. Medial injury in knee dislocations: What are the common injury patterns and surgical outcomes? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2658–66. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3483-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skendzel JG, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM. Diagnosis and management of the multiligament-injured knee. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42:234–42. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2012.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ríos A, Villa A, Fahandezh H, de José C, Vaquero J. Results after treatment of traumatic knee dislocations: A report of 26 cases. J Trauma. 2003;55:489–94. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000043921.09208.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong CH, Tan JL, Chang HC, Khin LW, Low CO. Knee dislocations – A retrospective study comparing operative versus closed immobilization treatment outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:540–4. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0490-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dedmond BT, Almekinders LC. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of knee dislocations: A meta-analysis. Am J Knee Surg. 2001;14:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geeslin AG, Moulton SG, LaPrade RF. A systematic review of the outcomes of posterolateral corner knee injuries, part 1: Surgical treatment of acute injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1336–42. doi: 10.1177/0363546515592828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Görmeli G, Görmeli CA, Elmalı N, Karakaplan M, Ertem K, Ersoy Y. Outcome of the treatment of chronic isolated and combined posterolateral corner knee injuries with 2- to 6-year followup. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:1363–8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strobel MJ, Schulz MS, Petersen WJ, Eichhorn HJ. Combined anterior cruciate ligament, posterior cruciate ligament, and posterolateral corner reconstruction with autogenous hamstring grafts in chronic instabilities. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:182–92. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzurbakis M, Diamantopoulos A, Xenakis T, Georgoulis A. Surgical treatment of multiple knee ligament injuries in 44 patients: 2-8 years followup results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:739–49. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fanelli GC, Orcutt DR, Edson CJ. The multiple-ligament injured knee: Evaluation, treatment, and results. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:471–86. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stannard JP, Bauer KL. Current concepts in knee dislocations: PCL, ACL, and medial sided injuries. J Knee Surg. 2012;25:287–94. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harner CD, Waltrip RL, Bennett CH, Francis KA, Cole B, Irrgang JJ, et al. Surgical management of knee dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:262–73. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jari S, Shelbourne KD. Nonoperative or delayed surgical treatment of combined cruciate ligaments and medial side knee injuries. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2001;9:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tay AK, MacDonald PB. Complications associated with treatment of multiple ligament injured (dislocated) knee. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2011;19:153–61. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e31820e6e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang W, Yao J, He Y, Sun W, Huang Y, Kong D, et al. The timing of surgical treatment of knee dislocations: A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:3108–13. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karataglis D, Bisbinas I, Green MA, Learmonth DJ. Functional outcome following reconstruction in chronic multiple ligament deficient knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:843–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fanelli GC, Edson CJ. Combined posterior cruciate ligament-posterolateral reconstructions with Achilles tendon allograft and biceps femoris tendon tenodesis: 2- to 10-year followup. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shelbourne KD, Haro MS, Gray T. Knee dislocation with lateral side injury: Results of an en masse surgical repair technique of the lateral side. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1105–16. doi: 10.1177/0363546507299444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wascher DC, Becker JR, Dexter JG, Blevins FT. Reconstruction of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments after knee dislocation. Results using fresh-frozen non irradiated allografts. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:189–96. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270021301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dwyer T, Marx R, Whelan D. Outcomes of treatment of multiple ligament knee injuries. J Knee Surg. 2012;25:317–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernstein J. Early versus delayed reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament: A decision analysis approach. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:e48. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meuffels DE, Poldervaart MT, Diercks RL, Fievez AW, Patt TW, Hart CP, et al. Guideline on anterior cruciate ligament injury. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:379–86. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.704563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stannard JP, Brown SL, Farris RC, McGwin G, Jr, Volgas DA. The posterolateral corner of the knee: Repair versus reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:881–8. doi: 10.1177/0363546504271208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mariani PP, Santoriello P, Iannone S, Condello V, Adriani E. Comparison of surgical treatments for knee dislocation. Am J Knee Surg. 1999;12:214–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Owens BD, Neault M, Benson E, Busconi BD. Primary repair of knee dislocations: Results in 25 patients (28 knees) at a mean followup of four years. J Orthop Traumatol. 2007;21:92–6. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3180321318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levy BA, Krych AJ, Shah JP, Morgan JA, Stuart MJ. Staged protocol for initial management of the dislocated knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:1630–7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1209-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Black BS, Stannard JP. Repair versus reconstruction in acute posterolateral instability of the knee. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2015;23:22–6. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smyth M, Koh J. A review of surgical and nonsurgical outcomes of medial knee injuries. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2015;23:15–22. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith P, Bollier M. Anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament injuries. J Knee Surg. 2014;27:359–68. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1381961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Björkman P, Sandelin J, Harilainen A. A randomized prospective controlled study with 5-year followup of cross-pin femoral fixation versus metal interference screw fixation in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:2353–9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ibrahim SA, Abdul Ghafar S, Marwan Y, Mahgoub AM, Al Misfer A, Farouk H, et al. Intratunnel versus extratunnel autologous hamstring double-bundle graft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A comparison of 2 femoral fixation procedures. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:161–8. doi: 10.1177/0363546514554189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ho WP, Lee CH, Huang CH, Chen CH, Chuang TY. Clinical results of hamstring autografts in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A comparison of femoral knot/press-fit fixation and interference screw fixation. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:823–32. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scannell BP, Loeffler BJ, Hoenig M, Peindl RD, D’Alessandro DF, Connor PM, et al. Biomechanical comparison of hamstring tendon fixation devices for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Part 2. Four tibial devices. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44:82–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weber AE, Delos D, Oltean HN, Vadasdi K, Cavanaugh J, Potter HG, et al. Tibial and femoral tunnel changes after ACL reconstruction: A prospective 2-year longitudinal MRI study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:1147–56. doi: 10.1177/0363546515570461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bourke HE, Salmon LJ, Waller A, Winalski CS, Williams HA, Linklater JM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of osteoconductive fixation screws for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A comparison of the calaxo and milagro screws. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leiter JR, Gourlay R, McRae S, de Korompay N, MacDonald PB. Long term followup of ACL reconstruction with hamstring autograft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:1061–9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-013-2466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samuelsen BT, Webster KE, Johnson NR, Hewett TE, Krych AJ. Hamstring autograft versus patellar tendon autograft for ACL reconstruction: Is there a difference in graft failure rate? A meta-analysis of 47,613 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5278-9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5278-9. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xie X, Liu X, Chen Z, Yu Y, Peng S, Li Q. A meta-analysis of bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft versus four-strand hamstring tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2015;22:100–10. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li S, Chen Y, Lin Z, Cui W, Zhao J, Su W, et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials comparing hamstring autografts versus bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts for the reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:1287–97. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yao LW, Wang Q, Zhang L, Zhang C, Zhang B, Zhang YJ, et al. Patellar tendon autograft versus patellar tendon allograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25:355–65. doi: 10.1007/s00590-014-1481-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li S, Su W, Zhao J, Xu Y, Bo Z, Ding X, et al. A meta-analysis of hamstring autografts versus bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts for reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Knee. 2011;18:287–93. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gifstad T, Foss OA, Engebretsen L, Lind M, Forssblad M, Albrektsen G, et al. Lower risk of revision with patellar tendon autografts compared with hamstring autografts: A registry study based on 45,998 primary ACL reconstructions in Scandinavia. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2319–28. doi: 10.1177/0363546514548164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]